|

Vocapedia >

Economy

The rich, the wealthy, billionaires,

centibillionaires

Andrzej Krauze

Comment cartoon

The Guardian

Thursday January 2, 2003

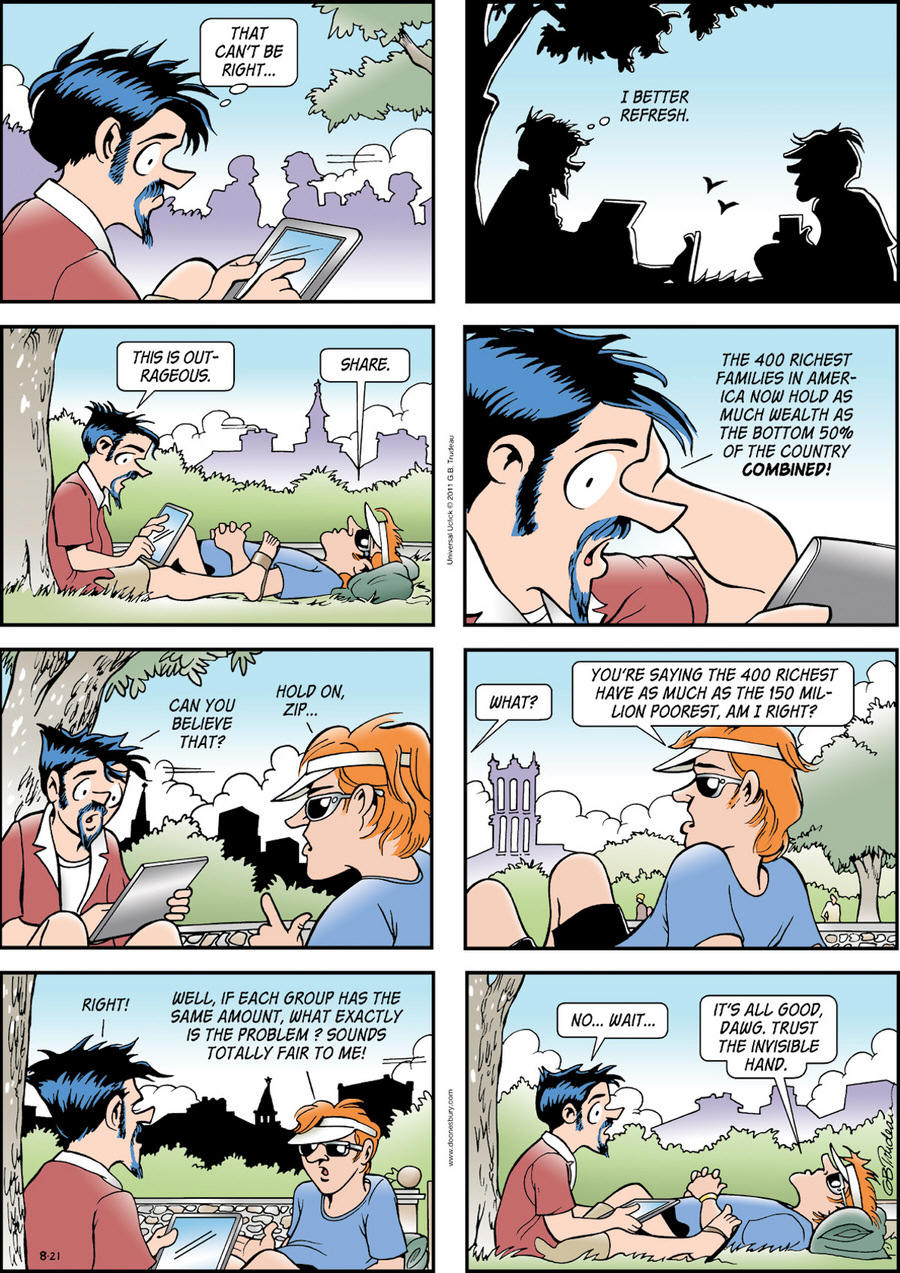

Doonesbury

political cartoon

Garry Trudeau

GoComics

August 21 2011

http://www.gocomics.com/doonesbury/2011/08/21

the better off

better off

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/11/09/

are-older-americans-better-off/

the well-off

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/24/

middle-class-living-standards

less well-off

students

affluent

the seriously affluent

fat-cat bosses

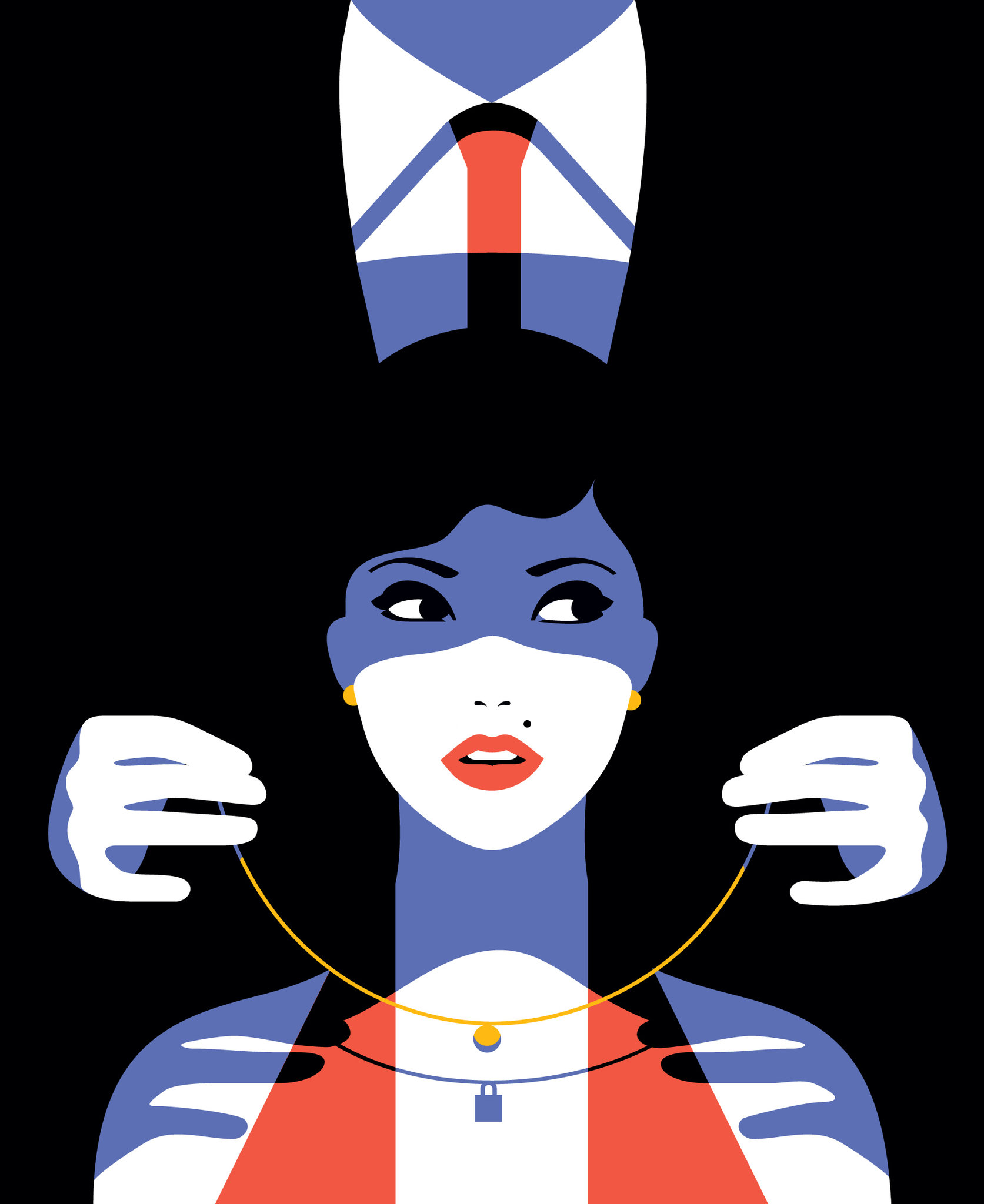

Illustration: Malika Favre

Poor Little Rich

Women

By WEDNESDAY MARTIN

NYT

MAY 16, 2015

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/17/

opinion/sunday/poor-little-rich-women.html

rich

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/10/

944620768/theres-rich-and-theres-jeff-bezos-

rich-meet-the-members-of-the-100-billion-club

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/10/

opinion/sunday/stop-pretending-youre-not-rich.html

rich people / the rich

UK / USA

2025

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/06/

books/review/evan-osnos-the-haves-and-have-yachts.html

2024

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/28/

world/europe/musk-support-for-german-far-right-afd.html

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/21/

rich-powerful-silencing-hold-to-account-slapps

2023

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/dec/11/

megayachts-environment-carbon-emissions-ban

2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/

opinion/inequality-america-paul-krugman.html

https://www.propublica.org/article/

the-bailout-is-working-for-the-rich - May 10, 2020

https://www.npr.org/2020/04/15/

834247954/the-rich-really-are-different-they-can-shelter-in-nicer-places

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/05/

style/the-rich-are-preparing-for-coronavirus-differently.html

2019

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/26/

nyregion/ken-griffin-238-million-penthouse.html

2018

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/07/02/

us/homeless-los-angeles-homelessness.html

2017

http://www.gocomics.com/phil-hands/2017/03/17

2016

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/24/

business/economy/velvet-rope-economy.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/11/

upshot/for-the-poor-geography-is-life-and-death.html

2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/23/

opinion/giving-billions-to-the-rich.html

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/28/

rich-poor-children-parents-holiday-food-camps

2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/10/

opinion/dont-soak-the-rich.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/29/

opinion/paul-krugman-our-invisible-rich.html

2013

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/05/

rich-people-just-care-less/

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/10/

the-rich-get-richer-through-the-recovery/

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/26/

opinion/the-rich-get-even-richer.html

http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/22/

do-we-hate-the-rich-or-dont-we/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2008/aug/04/

workandcareers.executivesalaries

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2004/jul/07/

money

rich lists

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/rich-lists

the rich

and powerful UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/21/

rich-powerful-silencing-hold-to-account-slapps

the 1 percent / the

1% UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jul/19/

how-to-spend-it-the-shopping-list-for-the-1-percent

the 1 percent / the

1% USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/08/

919497813/hes-part-of-the-1-and-he-thinks-his-taxes-aren-t-high-enough

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/

opinion/obamas-war-on-inequality.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/01/

opinion/sunday/ultra-luxury-for-the-1.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/03/

books/review-the-economics-of-inequality-by-thomas-piketty.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/20/

opinion/krugman-the-undeserving-rich.html

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/18/

the-1-percent-are-only-half-the-problem/

the world’s richest

people UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/feb/03/

jeff-bezos-and-the-world-amazon-made

the world's 10

richest people UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jan/26/

the-worlds-10-richest-people-made-540bn-in-a-year-we-need-a-greed-tax

the world’s richest

person USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/27/

539798420/prime-spot-on-the-billionaire-list-jeff-bezos-was-briefly-worlds-richest-man

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/jul/27/

amazon-founder-jeff-bezos-worlds-richest-man-bill-gates

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/23/

opinion/bill-gatess-clean-energy-moon-shot.html

the world’s richest

man USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/28/

world/europe/musk-support-for-german-far-right-afd.html

the richest man on

the planet USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/06/04/

1102327987/elon-musk-sec-tweets-lawsuit-power

Just eight men own

the same wealth

as 3.6 billion people living in poverty

— that's half the

population of the planet. USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/01/25/

511594991/what-the-stat-about-the-8-richest-men-

doesnt-tell-us-about-inequality

tax the rich

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/03/

sunday-review/tax-rich-irs.html

Taxing the Rich, New York Style

USA December 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/12/08/

cuomos-tax-deal-who-benefits-the-most/

life expectancy gap

between rich and poor

people in England UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/jul/02/

poor-in-uk-dying-10-years-earlier-than-rich

rich people

UK

https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/commentators/dominic-lawson/

dominic-lawson-rich-people-lack-something-vital-ndash-even-more-money-

1128220.html - 16 December 2008

rich people > life

expectancy USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/24/

upshot/rich-people-are-living-longer-thats-tilting-social-security-in-their-favor.html

rich women

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/17/

opinion/sunday/poor-little-rich-women.html

the very rich

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/

opinion/jackson-hole-coronavirus.html

the rich and powerful

opulence

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/03/21/

1164275807/poverty-by-america-matthew-desmond-inequality

the super-rich

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/

the-super-rich

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/jun/02/

beyonce-jay-z-california-record-malibu-mansion

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/nov/07/

billion-dollar-race-ageing-planet-old-age

https://www.theguardian.com/news/commentisfree/2021/jan/26/

covid-inequality-worse-squeeze-super-rich

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/05/

super-tall-super-skinny-super-expensive-

the-pencil-towers-of-new-yorks-super-rich

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/02/

forget-philanthropy-super-rich-should-be-paying-proper-taxes

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2018/aug/01/

why-the-super-rich-are-taking-their-mega-boats-into-uncharted-waters

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/nov/12/

credit-suisse-global-wealth-brexit-super-rich

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/08/

mossack-fonseca-law-firm-hide-money-panama-papers

http://www.theguardian.com/money/2014/apr/07/

londons-most-expensive-street-kensington-palace-gardens

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/jun/01/

top-earners-millionaires-inequality-city-finance

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/feb/24/

why-super-rich-love-uk

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/jun/23/

art.artnews

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/dec/24/

comment.tax

the super-rich

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/10/

business/dealbook/how-the-twinkie-made-the-super-rich-even-richer.html

mega-rich

USA

https://www.gocomics.com/stevebreen/2021/06/12

Yours for $250m:

the

most expensive house in America UK

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/23/

most-expensive-house-in-america-los-angeles

Super-tall,

super-skinny, super-expensive:

the 'pencil towers'

of New York's super-rich UK

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/05/

super-tall-super-skinny-super-expensive-

the-pencil-towers-of-new-yorks-super-rich

America’s Top 15 Earners

and What

They Reveal About the U.S. Tax System

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

americas-top-15-earners-

and-what-they-reveal-about-the-us-tax-system - April

13, 2022

£1m-plus earners

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/jun/01/

top-earners-millionaires-inequality-city-finance

the

ultra-rich / the ultrarich

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jul/15/

food-systems-collapse-plutocrats-life-on-earth-climate-breakdown

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jul/19/

how-to-spend-it-the-shopping-list-for-the-1-percent

the ultrarich

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/14/nyregion/

14partying.html

USA > richest

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/

jul/23/tech-industry-wealth-futurism-transhumanism-singularity

Britain’s richest 10% UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/24/

britain-richest-10-per-cent-wealthy-inequality-labour-private-schools

the richest 10% of the population

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/jan/27/

unequal-britain-report

wealth

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2025/jan/20/

wealth-of-worlds-billionaires-grew-by-2tn-in-2024-

report-finds

royal wealth

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/may/04/

why-we-put-royal-wealth-under-the-microscope-on-eve-of-coronation

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2023/may/04/

cost-of-the-crown-part-4-calculating-king-charles-wealth-

podcast - Guardian podcast

the wealthy

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/02/

coronavirus-cities-elite-community

the wealthy

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

irs-files-taxes-wash-sales-goldman-sachs - February 9, 2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/

opinion/coronvairus-economy-history.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/23/

opinion/giving-billions-to-the-rich.html

the

ultra-wealthy UK

https://www.theguardian.com/science/audio/2023/nov/21/

superyachts-and-private-jets-the-carbon-impact-of-the-polluter-elite-

podcast

ultrawealthy

N USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

how-these-ultrawealthy-politicians-avoided-paying-taxes - November 4, 2021

the

ultrawealthy USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

the-ultrawealthy-have-hijacked-roth-iras-

the-senate-finance-chair-is-eyeing-a-crackdown

- June 25, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/24/

business/ceos-pandemic-compensation.html

https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=1_l981f9zik -

NYT - 2 October 2018

llustration / editorial cartoon: Ben Jennings

Ben

Jennings on the latest UK rich list – cartoon

G

Sun

13 May 2018 18.36 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2018/may/13/

ben-jennings-on-the-latest-uk-rich-list-cartoon

The richest people in Britain

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2018/may/13/

ben-jennings-on-the-latest-uk-rich-list-cartoon

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/18/

sunday-times-rich-list

rich lists

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/

rich-lists

Britain has world's most billionaires per capita

UK

11 May 2014

Sunday Times Rich List

reveals 104 billionaires sharing fortune of £301bn,

but few pay tax as they are not domiciled in UK

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/11/

britain-worlds-most-billionaires-per-capita

The 1,000 wealthiest

people in the UK are now worth £547bn,

not counting what’s

in their bank accounts,

according to the

latest Sunday Times Rich List UK

26 April 2015

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/apr/26/

crisis-what-crisis-britains-richest-double-their-wealth-in-10-years

Forbes >

World's billonaires list

https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/

Forbes 400:

the world's wealthiest people

2012 UK

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2012/sep/19/

forbes-400-bill-gates-rich-list

Forbes rich list:

the

world's wealthiest people UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/mar/10/

forbes-rich-list-carlos-slim

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/gallery/2010/mar/10/

forbes-rich-lists

list of the 400 richest Americans

UK

2006

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2006/sep/22/

usnews.internationalnews

millionaire

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/aug/27/

number-of-millionaires-in-uk-rises-by-200000

millionaire

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/06/

your-money/skimping-on-the-splurges-even-as-a-millionaire.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/

style/in-los-angeles-a-nimby-battle-pits-millionaires-vs-billionaires.html

UK, USA > billionaire

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2025/jan/20/

wealth-of-worlds-billionaires-grew-by-2tn-in-2024-

report-finds

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/03/

buff-billionaires-jeff-bezos-mark-zuckerberg-body-image

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/dec/19/

ten-billionaires-reap-400bn-boost-to-wealth-during-pandemic

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/24/

billionaires-coronavirus-not-in-the-same-boat

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/12/

americas-billionaire-class-donations

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jul/18/

elon-musk-apologises-for-calling-thai-cave-rescue-diver-a-pedo

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jul/13/

billionaires-bought-brexit-controlling-britains-political-system

http://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2016/apr/13/

homes-for-1m-in-pictures

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/11/

britain-worlds-most-billionaires-per-capita

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/11/

rich-list-more-than-100-billionaires-in-britain-for-the-first-time

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/jan/26/

superyacht-billionaires-helipads-tennis-courts

http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/aug/06/

jeff-bezos-amazon-washington-post

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/oct/13/

warren-buffett-65m

Biden speech

Political cartoon

Pat Bagley is the

staff cartoonist

for The Salt Lake

Tribune in Salt Lake City, Utah,

and an author and

illustrator of several books.

His cartoons are

syndicated nationally by Cagle Cartoons.

Cagle Cartoons

April 29, 2021

https://www.cagle.com/pat-bagley/2021/04/biden-speech

Related

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/22/

business/economy/biden-taxes.html

billionaire USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/07/

magazine/billionaires.html

https://www.npr.org/2022/04/06/

1091141947/forbes-billionaires-wealth-shrunk-russia

https://www.propublica.org/article/

you-may-be-paying-a-higher-tax-rate-than-a-billionaire - June 8, 2021

https://www.cagle.com/pat-bagley/2021/04/

biden-speech

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/05/

920314309/pandemic-profiteers-

why-billionaires-are-getting-richer-during-an-economic-crisi

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/

technology/tech-billionaires-education-zuckerberg-facebook-hastings.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/17/

510271789/gulf-between-richest-and-poorest-is-wider-than-previously-thought-oxfam-says

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/

opinion/sunday/billionaires-to-the-barricades.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/

style/in-los-angeles-a-nimby-battle-pits-millionaires-vs-billionaires.html

http://www.npr.org/blogs/alltechconsidered/2014/01/26/

266685819/billionaire-compares-outrage-over-rich-in-s-f-to-kristallnacht

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/19/

realestate/rising-tower-in-manhattan-takes-on-sheen-as-billionaires-haven.html

https://www.reuters.com/article/

us-billionaires-crisis/billionaires-luster-dims-as-crisis-grips-idUSTRE4BT3TZ

20081230

centibillionaires USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/10/

944620768/theres-rich-and-theres-jeff-bezos-

rich-meet-the-members-of-the-100-billion-club

trillionaire

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/18/

the-big-idea-should-we-worry-about-trillionaires

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/05/

trillionaire-economy-democracy-ultra-rich

https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/dec/19/

when-will-we-see-the-worlds-first-trillionaire-jeff-bezos-bill-gates

Billionaires' basements:

the luxury bunkers

making holes in London

streets UK 2012

A new billionaires' craze

for building elaborate

subterranean extensions

is making swiss cheese of London's

poshest streets

– but at what cost?

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/nov/09/

billionaires-basements-london-houses-architecture

Outrageously

expensive homes – in pictures UK 27 April 2016

http://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2016/apr/27/

outrageously-expensive-homes-in-pictures

Homes for £1m –

in pictures UK 13 April 2016

From a Shropshire

manor

to a Greek mansion,

these luxury

properties

are fit for a millionaire

http://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2016/apr/13/

homes-for-1m-in-pictures

manor

USA

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/jun/02/

beyonce-jay-z-california-record-malibu-mansion

candy-asses

Oxbrige prats

jammy job (slang)

aristocrat

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/may/04/

cash-strapped-earl-blencathra-sale

aristocracy

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/sep/07/

how-the-aristocracy-preserved-their-power

kleptocrats UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/sep/04/

britain-dirty-money-laundry-mps-amendment-

economic-crime-corporate-transparency-bill

plutocrats

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jul/15/

food-systems-collapse-plutocrats-life-on-earth-climate-breakdown

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/nov/01/

plutocrats-super-rich-freeland-review

Plutocrats:

The Rise of the New Global Super Rich

by Chrystia Freeland – review

UK

2012

Outrageous fortunes abound

in this absorbing study

of the world's wealthiest men

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/nov/01/

plutocrats-super-rich-freeland-review

the plutocrats

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/27/

opinion/krugman-paranoia-of-the-plutocrats.html

plutocracy

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/05/

the-walkie-talkie-is-a-sty-in-londons-eye-and-proves-we-cant-say-no-to-money

plutocracy

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/04/

opinion/krugman-plutocracy-paralysis-perplexity.html

moneyocracy

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2015/mar/05/

eddie-izzard-locks-horns-landlords-chelsea-social-housing-estate

the money-laden elite

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/nov/01/

plutocrats-super-rich-freeland-review

Covid-19

> pandemic 'profiteers' USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/05/

920314309/pandemic-profiteers-

why-billionaires-are-getting-richer-during-an-economic-crisi

thrive

luxurious

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/26/

business/26fall.html

luxury

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2016/apr/13/

homes-for-1m-in-pictures

ultra-luxury

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/01/

opinion/sunday/ultra-luxury-for-the-1.html

affluence

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/26/

business/26fall.html

fortune

USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/27/

539798420/prime-spot-on-the-billionaire-list-jeff-bezos-was-briefly-worlds-richest-man

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/09/

business/charles-wyly-dies-at-77-amassed-a-fortune-with-brother.html

wealth

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/feb/07/

revealed-queen-lobbied-for-change-in-law-to-hide-her-private-wealth

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/dec/19/

ten-billionaires-reap-400bn-boost-to-wealth-during-pandemic

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/sep/21/

how-to-hide-it-inside-secret-world-of-wealth-managers

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jul/29/

stephen-hawking-brexit-wealth-resources

wealth

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/03/26/

1240890579/truth-social-trump-media-and-technology-group-trump-net-worth

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/

opinion/coronavirus-wealth-tax.html

https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/dec/19/

when-will-we-see-the-worlds-first-trillionaire-jeff-bezos-bill-gates

http://www.npr.org/2015/12/12/

459464289/more-wealth-in-fewer-cities-why-inequality-divides-america

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/

opinion/sunday/the-ethics-of-wealth.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/24/

opinion/krugman-wealth-over-work.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/19/

opinion/to-reduce-inequality-tax-wealth-not-income.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/06/

magazine/romneys-former-bain-partner-makes-a-case-for-inequality.html

wealth managers

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/sep/21/

how-to-hide-it-inside-secret-world-of-wealth-managers

super-wealth

USA

https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/dec/19/

when-will-we-see-the-worlds-first-trillionaire-jeff-bezos-bill-gates

income sgregation USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/27/

opinion/campaign-stops/how-the-other-fifth-lives.html

https://cepa.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/

the%20continuing%20increase%20in%20income%20segregation%20march2016.pdf

wealth segregation

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/jul/17/

politics.money

wealth gap

inequality

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/

inequality

wealth inequality

USA

http://www.npr.org/2015/12/12/

459464289/more-wealth-in-fewer-cities-why-inequality-divides-america

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/22/

opinion/22tue2.html

income and wealth inequality

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/24/

opinion/krugman-wealth-over-work.html

economic inequality in the United States

USA

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/18/

the-1-percent-are-only-half-the-problem/

income distribution

the top 20 percent >

self-segregation of a privileged fifth of

the population USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/27/

opinion/campaign-stops/how-the-other-fifth-lives.html

money-based caste system

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/24/

business/economy/velvet-rope-economy.htm

privilege USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/24/

business/economy/velvet-rope-economy.html

health

inequality UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/sep/11/

health-inequality-affects-us-all-michael-marmot

income gap

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/21/

business/economy/tolerance-for-income-gap-may-be-ebbing-economic-scene.html

mega-earners

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/aug/24/

mega-earners-pay-commission

high earners

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2010/oct/04/

child-benefit-scrapped-high-earners

high flyers

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/may/25/

gender.law1

high society

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/20/

obituaries/jayne-wrightsman-dead.html

silver spoon

public school

"Eton-educated

guys in white linen suits" UK

http://www.theguardian.com/media/2003/dec/05/

bbc.broadcasting

class snobbery

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/may/22/

nick-clegg-british-class-snobbery

snobbery

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/sep/13/

lymington-rejects-wetherspoons-pub

snooty

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/sep/13/

lymington-rejects-wetherspoons-pub

The Yellowstone

Club USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/14/business/14yellow.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/30/us/30gated.html

lavish lifestyle

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/11/

business/11fraud.html

toff

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2011/apr/18/

morning-suit-pass-notes

posh Britain

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/21/

-sp-posh-britain-the-riot-club-bullingdon-privilege

exclusive places

USA

Revealed:

Britain's most

expensive places to rent a home UK

Esher, Surrey, is most expensive place

to rent two-bedroom home outside

capital

with average monthly cost of

£1,913.

But London rents beat this figure

by 15%

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/may/01/

revealed-britains-most-expensive-places-to-rent-a-home

gentrify

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/22/

opinion/l22brooks.html

gentrification UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/live/2016/sep/16/

will-boundary-changes-alter-politics-for-good-join-our-live-look-at-the-week

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/video/2013/aug/02/

alex-wheatle-gentrification-brixton-video

gentrification

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/28/

opinion/affordable-housing-vs-gentrification.html

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2015/10/01/blogs/

bracing-for-gentrification-in-the-south-bronx/s/20100110-lens-kambers-slide-NTZR.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/09/23/

435293852/an-atlanta-neighborhood-tries-to-redefine-gentrification

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/23/us/

high-rents-elbow-latinos-from-san-franciscos-mission-district.html

http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/may/13/

harlem-gentrification-new-york-race-black-white

gentrifying

http://www.npr.org/2017/01/16/

505606317/d-c-s-gentrifying-neighborhoods-a-careful-mix-of-newcomers-and-old-timers

philanthropy

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/30/

business/30charity.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/jul/15/

microsoft-paul-allen-charity

philanthropy >

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/organization/

bill-and-melinda-gates-foundation

https://www.theguardian.com/world/

bill-and-melinda-gates-foundation

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/13/

business/from-the-gates-foundation-direct-investment-not-just-grants.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/19/us/

19gates.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/jul/12/

bill-and-melinda-gates-foundation

education-related philanthropy

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/19/us/

19gates.html

philantropic

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/25/

1040728667/philanthropic-billionaire-walter-scott-dies-at-90

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/us/

philadelphias-success-in-helping-the-homeless-gets-a-philanthropic-boost.html

philanthropist

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/24/

arts/music/william-h-scheide-100-philanthropist-is-dead.html

charity

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/jul/15/

microsoft-paul-allen-charity

charity shop

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/oct/03/

glasgow-charity-shop-donation-cancer

UK > A divided nation

2004

The richest...

Rank / Place / Postcode / Average income

1 / Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent / ME19 4 / £62,000

2 / Elvetham Heath, Fleet, Surrey / GU51 1 / £61,000

3 / Hammersmith, London / SW13 8 / £59,000

4 / City of London / EC2Y 8 / £58,000

5 / Epsom, Surrey / KT19 7 / £58,000

6 / Grange Park, Northampton / NN4 5 / £58,000

7 / Sevenoaks, Kent / TN15 9 / £57,000

8 / Wokingham, Berkshire / RG40 5 / £57,000

9 / Leatherhead, Surrey / KT22 0 / £57,000

10 / Bracknell, Berkshire / RG42 7 / £56,000

and the poorest...

Rank / Place / Postcode / Average income

1 / Newport Road, Middlesbrough / TS1 5 / £12,000

2 / St Matthews, Leicester / LE1 2 / £13,000

3 / Middlesbrough / TS1 2 / £14,000

4 / Possil Park, Glasgow / G22 5 / £14,000

5 / Trafford Way, Doncaster / DN1 3 / £14,000

6 / Haswell Drive, Knowsley, Merseyside / L28 5 / £14,000

7 / Everton, Liverpool / L5 0 / £14,000

8 / Birkenhead, Merseyside / CH41 3 / £14,000

9 / Parkhead, Glasgow / G40 3 / £14,000

10 / Lawrence Street, Sunderland / SR1 2 / £14,000

Source: CACI

The Observer, 20

June 2004

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/jun/20/

britishidentity.jamiedoward

Corpus of news articles

Economy > The rich, the wealthy

The Rich Get Even Richer

March 25, 2012

The New York Times

By STEVEN RATTNER

NEW statistics show an ever-more-startling divergence between

the fortunes of the wealthy and everybody else — and the desperate need to

address this wrenching problem. Even in a country that sometimes seems inured to

income inequality, these takeaways are truly stunning.

In 2010, as the nation continued to recover from the recession, a dizzying 93

percent of the additional income created in the country that year, compared to

2009 — $288 billion — went to the top 1 percent of taxpayers, those with at

least $352,000 in income. That delivered an average single-year pay increase of

11.6 percent to each of these households.

Still more astonishing was the extent to which the super rich got rich faster

than the merely rich. In 2010, 37 percent of these additional earnings went to

just the top 0.01 percent, a teaspoon-size collection of about 15,000 households

with average incomes of $23.8 million. These fortunate few saw their incomes

rise by 21.5 percent.

The bottom 99 percent received a microscopic $80 increase in pay per person in

2010, after adjusting for inflation. The top 1 percent, whose average income is

$1,019,089, had an 11.6 percent increase in income.

This new data, derived by the French economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez

from American tax returns, also suggests that those at the top were more likely

to earn than inherit their riches. That’s not completely surprising: the rapid

growth of new American industries — from technology to financial services — has

increased the need for highly educated and skilled workers. At the same time,

old industries like manufacturing are employing fewer blue-collar workers.

The result? Pay for college graduates has risen by 15.7 percent over the past 32

years (after adjustment for inflation) while the income of a worker without a

high school diploma has plummeted by 25.7 percent over the same period.

Government has also played a role, particularly the George W. Bush tax cuts,

which, among other things, gave the wealthy a 15 percent tax on capital gains

and dividends. That’s the provision that caused Warren E. Buffett’s secretary to

have a higher tax rate than he does.

As a result, the top 1 percent has done progressively better in each economic

recovery of the past two decades. In the Clinton era expansion, 45 percent of

the total income gains went to the top 1 percent; in the Bush recovery, the

figure was 65 percent; now it is 93 percent.

Just as the causes of the growing inequality are becoming better known, so have

the contours of solving the problem: better education and training, a fairer tax

system, more aid programs for the disadvantaged to encourage the social mobility

needed for them escape the bottom rung, and so on.

Government, of course, can’t fully address some of the challenges, like

globalization, but it can help.

By the end of the year, deadlines built into several pieces of complex

legislation will force a gridlocked Congress’s hand. Most significantly, all of

the Bush tax cuts will expire. If Congress does not act, tax rates will return

to the higher, pre-2000, Clinton-era levels. In addition, $1.2 trillion of

automatic spending cuts that were set in motion by the failure of the last

attempt at a deficit reduction deal will take effect.

So far, the prospects for progress are at best worrisome, at worst terrifying.

Earlier this week, House Republicans unveiled an unsavory stew of highly

regressive tax cuts, large but unspecified reductions in discretionary spending

(a category that importantly includes education, infrastructure and research and

development), and an evisceration of programs devoted to lifting those at the

bottom, including unemployment insurance, food stamps, earned income tax credits

and many more.

Policies of this sort would exacerbate the very problem of income inequality

that most needs fixing. Next week’s package from House Democrats will almost

certainly be more appealing. And to his credit, President Obama has spoken

eloquently about the need to address this problem. But with Democrats in the

minority in the House and an election looming, passage is unlikely.

The only way to redress the income imbalance is by implementing policies that

are oriented toward reversing the forces that caused it. That means letting the

Bush tax cuts expire for the wealthy and adding money to some of the programs

that House Republicans seek to cut. Allowing this disparity to continue is both

bad economic policy and bad social policy. We owe those at the bottom a fairer

shot at moving up.

Steven Rattner is a contributing writer for Op-Ed

and a longtime

Wall Street executive.

This article has been revised

to reflect the following correction:

Correction: March 26, 2012

Due to a typo,

an earlier version referred incorrectly

to the distribution of

income gains made

during the Clinton expansion.

Forty-five percent of the total

income gains

went to the top 1 percent,

not to the top 11 percent.

The Rich Get Even Richer,

NYT,

25.3.2012,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/26/

opinion/the-rich-get-even-richer.html

Inequality Undermines Democracy

March 20, 2012

The New York Times

By EDUARDO PORTER

Americans have never been too worried about the income gap.

The gap between the rich and the rest has been much wider in the United States

than in other developed nations for decades. Still, polls show we are much less

concerned about it than people in those other nations are.

Policy makers haven’t cared much either. The United States does less than other

rich countries to transfer income from the affluent to the less fortunate. Even

as the income gap has grown enormously over the last 30 years, government has

done little to curb the trend.

Our tolerance for a widening income gap may be ebbing, however. Since Occupy

Wall Street and kindred movements highlighted the issue, the chasm between the

rich and ordinary workers has become a crucial talking point in the Democratic

Party’s arsenal. In a speech in Osawatomie, Kan., last December, President Obama

underscored how “the rungs of the ladder of opportunity had grown farther and

farther apart, and the middle class has shrunk.”

There are signs that the political strategy has traction. Inequality isn’t quite

the top priority of voters: only 17 percent of Americans think it is extremely

important for the government to try to reduce income and wealth inequality,

according to a Gallup survey last November. That is about half the share that

said reigniting economic growth was crucial.

But a slightly different question indicates views have changed: 29 percent said

it was extremely important for the government to increase equality of

opportunity. More significant, 41 percent said that there was not much

opportunity in America, up from 17 percent in 1998.

Americans have been less willing to take from the rich and give to the poor in

part because of a belief that each of us has a decent shot at prosperity. In

1952, 87 percent of Americans thought there was plenty of opportunity for

progress; only 8 percent disagreed. As income inequality has grown, though, many

have changed their minds.

From 1993 to 2010, the incomes of the richest 1 percent of Americans grew 58

percent while the rest had a 6.4 percent bump. There is little reason to think

the trend will go into reverse any time soon, given globalization and

technological change, which have weighed heavily on the wages of less educated

workers who compete against machines and cheap foreign labor while increasing

the returns of top executives and financiers.

The income gap narrowed briefly during the Great Recession, as plummeting stock

prices shrunk the portfolios of the rich. But in 2010, the first year of

recovery, the top 1 percent of Americans captured 93 percent of the income

gains.

Under these conditions, perhaps it is unsurprising that a growing share of

Americans have lost faith in their ability to get ahead.

We have accepted income inequality in the past partly because of the belief that

capitalism can’t work without it. If entrepreneurs invest and workers improve

their skills to improve their lot in life, a government that heavily taxed the

rich to give to the poor could destroy that incentive and stymie economic growth

that benefits everybody.

The nation’s relatively fast growth over the last three decades appeared to

support this view. The United States grew faster than advanced economies with a

more egalitarian distribution of income, like the European Union and Japan, so

keeping redistribution to a minimum while allowing markets to function unimpeded

was considered the best fuel.

Meanwhile, skeptics of income redistribution pointed out that inequality doesn’t

look so dire when it is viewed over a lifetime rather than at a single point in

time. One study found that about half the households in the poorest fifth of the

population moved to a higher quintile within a decade.

Even though the wealthy reaped most of growth’s rewards, critics of

redistribution noted that incomes grew over the last 30 years for all but the

poorest American families. And in the 1990s, a decade of soaring inequality,

even families in the bottom fifth saw their incomes rise.

Some economists have argued that inequality is not the right social ill to focus

on. “What matters is how the poor and middle class are doing and how much

opportunity they have,” said Scott Winship, an economist at the Brookings

Institution. “Until there is stronger evidence that inequality has a negative

effect on the life of the average person, I’m inclined to accept it.”

Perhaps Americans’ newfound concerns about their lack of opportunity are a

reaction to our economic doldrums, with high unemployment and stagnant incomes,

and have little to do with inequality. Perhaps these concerns will dissipate

when jobs become more plentiful.

Perhaps. Evidence is mounting, however, that inequality itself is obstructing

Americans’ shot at a better life.

Alan Krueger, Mr. Obama’s top economic adviser, offers a telling illustration of

the changing views on income inequality. In the 1990s he preferred to call it

“dispersion,” which stripped it of a negative connotation.

In 2003, in an essay called “Inequality, Too Much of a Good Thing” Mr. Krueger

proposed that “societies must strike a balance between the beneficial incentive

effects of inequality and the harmful welfare-decreasing effects of inequality.”

Last January he took another step: “the rise in income dispersion — along so

many dimensions — has gotten to be so high, that I now think that inequality is

a more appropriate term.”

Progress still happens, but there is less of it. Two-thirds of American families

— including four of five in the poorest fifth of the population — earn more than

their parents did 30 years earlier. But they don’t advance much. Four out of 10

children whose family is in the bottom fifth will end up there as adults. Only 6

percent of them will rise to the top fifth.

It is difficult to measure changes in income mobility over time. But some

studies suggest it is declining: the share of families that manage to rise out

of the bottom fifth of earnings has fallen since the early 1980s. So has the

share of people that fall from the top.

And on this count too, the United States seems to be trailing other developed

nations. Comparisons across countries suggest a fairly strong, negative link

between the level of inequality and the odds of advancement across the

generations. And the United States appears at extreme ends along both of these

dimensions — with some of the highest inequality and lowest mobility in the

industrial world.

The link makes sense: a big income gap is likely to open up other social

breaches that make it tougher for those lower down the rungs to get ahead. And

that is exactly what appears to be happening in the United States, where a

narrow elite is peeling off from the rest of society by a chasm of wealth, power

and experience.

The sharp rise in the cost of college is making it harder for lower-income and

middle-class families to progress, feeding education inequality.

Inequality is also fueling geographical segregation — pushing the homes of the

rich and poor further apart. Brides and grooms increasingly seek out mates with

similar levels of income and education. Marriages among less-educated people

have become much more likely to fail.

And a growing income gap has bred a gap in political clout that could entrench

inequality for a very long time. One study found that public spending on

education was lower in countries like Britain and the United States where the

rich participate more in the political process than the poor, and higher in

countries like Sweden and Denmark, where levels of political participation are

approximately similar across the income scale. If the very rich can use the

political system to slow or stop the ascent of the rest, the United States could

become a hereditary plutocracy under the trappings of liberal democracy.

One doesn’t have to believe in equality to be concerned about these trends. Once

inequality becomes very acute, it breeds resentment and political instability,

eroding the legitimacy of democratic institutions. It can produce political

polarization and gridlock, splitting the political system between haves and

have-nots, making it more difficult for governments to address imbalances and

respond to brewing crises. That too can undermine economic growth, let alone

democracy.

Inequality Undermines Democracy,

NYT,

20.3.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/21/

business/economy/tolerance-for-income-gap-

may-be-ebbing-economic-scene.html

Education Gap Grows

Between Rich and Poor,

Studies Say

February 9, 2012

The New York Times

By SABRINA TAVERNISE

WASHINGTON — Education was historically considered a great

equalizer in American society, capable of lifting less advantaged children and

improving their chances for success as adults. But a body of recently published

scholarship suggests that the achievement gap between rich and poor children is

widening, a development that threatens to dilute education’s leveling effects.

It is a well-known fact that children from affluent families tend to do better

in school. Yet the income divide has received far less attention from policy

makers and government officials than gaps in student accomplishment by race.

Now, in analyses of long-term data published in recent months, researchers are

finding that while the achievement gap between white and black students has

narrowed significantly over the past few decades, the gap between rich and poor

students has grown substantially during the same period.

“We have moved from a society in the 1950s and 1960s, in which race was more

consequential than family income, to one today in which family income appears

more determinative of educational success than race,” said Sean F. Reardon, a

Stanford University sociologist. Professor Reardon is the author of a study that

found that the gap in standardized test scores between affluent and low-income

students had grown by about 40 percent since the 1960s, and is now double the

testing gap between blacks and whites.

In another study, by researchers from the University of Michigan, the imbalance

between rich and poor children in college completion — the single most important

predictor of success in the work force — has grown by about 50 percent since the

late 1980s.

The changes are tectonic, a result of social and economic processes unfolding

over many decades. The data from most of these studies end in 2007 and 2008,

before the recession’s full impact was felt. Researchers said that based on

experiences during past recessions, the recent downturn was likely to have

aggravated the trend.

“With income declines more severe in the lower brackets, there’s a good chance

the recession may have widened the gap,” Professor Reardon said. In the study he

led, researchers analyzed 12 sets of standardized test scores starting in 1960

and ending in 2007. He compared children from families in the 90th percentile of

income — the equivalent of around $160,000 in 2008, when the study was conducted

— and children from the 10th percentile, $17,500 in 2008. By the end of that

period, the achievement gap by income had grown by 40 percent, he said, while

the gap between white and black students, regardless of income, had shrunk

substantially.

Both studies were first published last fall in a book of research, “Whither

Opportunity?” compiled by the Russell Sage Foundation, a research center for

social sciences, and the Spencer Foundation, which focuses on education. Their

conclusions, while familiar to a small core of social sciences scholars, are now

catching the attention of a broader audience, in part because income inequality

has been a central theme this election season.

The connection between income inequality among parents and the social mobility

of their children has been a focus of President Obama as well as some of the

Republican presidential candidates.

One reason for the growing gap in achievement, researchers say, could be that

wealthy parents invest more time and money than ever before in their children

(in weekend sports, ballet, music lessons, math tutors, and in overall

involvement in their children’s schools), while lower-income families, which are

now more likely than ever to be headed by a single parent, are increasingly

stretched for time and resources. This has been particularly true as more

parents try to position their children for college, which has become ever more

essential for success in today’s economy.

A study by Sabino Kornrich, a researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies at

the Juan March Institute in Madrid, and Frank F. Furstenberg, scheduled to

appear in the journal Demography this year, found that in 1972, Americans at the

upper end of the income spectrum were spending five times as much per child as

low-income families. By 2007 that gap had grown to nine to one; spending by

upper-income families more than doubled, while spending by low-income families

grew by 20 percent.

“The pattern of privileged families today is intensive cultivation,” said Dr.

Furstenberg, a professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania.

The gap is also growing in college. The University of Michigan study, by Susan

M. Dynarski and Martha J. Bailey, looked at two generations of students, those

born from 1961 to 1964 and those born from 1979 to 1982. By 1989, about

one-third of the high-income students in the first generation had finished

college; by 2007, more than half of the second generation had done so. By

contrast, only 9 percent of the low-income students in the second generation had

completed college by 2007, up only slightly from a 5 percent college completion

rate by the first generation in 1989.

James J. Heckman, an economist at the University of Chicago, argues that

parenting matters as much as, if not more than, income in forming a child’s

cognitive ability and personality, particularly in the years before children

start school.

“Early life conditions and how children are stimulated play a very important

role,” he said. “The danger is we will revert back to the mindset of the war on

poverty, when poverty was just a matter of income, and giving families more

would improve the prospects of their children. If people conclude that, it’s a

mistake.”

Meredith Phillips, an associate professor of public policy and sociology at the

University of California, Los Angeles, used survey data to show that affluent

children spend 1,300 more hours than low-income children before age 6 in places

other than their homes, their day care centers, or schools (anywhere from

museums to shopping malls). By the time high-income children start school, they

have spent about 400 hours more than poor children in literacy activities, she

found.

Charles Murray, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute whose book,

“Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010,” was published Jan. 31,

described income inequality as “more of a symptom than a cause.”

The growing gap between the better educated and the less educated, he argued,

has formed a kind of cultural divide that has its roots in natural social

forces, like the tendency of educated people to marry other educated people, as

well as in the social policies of the 1960s, like welfare and other government

programs, which he contended provided incentives for staying single.

“When the economy recovers, you’ll still see all these problems persisting for

reasons that have nothing to do with money and everything to do with culture,”

he said.

There are no easy answers, in part because the problem is so complex, said

Douglas J. Besharov, a fellow at the Atlantic Council. Blaming the problem on

the richest of the rich ignores an equally important driver, he said: two-earner

household wealth, which has lifted the upper middle class ever further from less

educated Americans, who tend to be single parents.

The problem is a puzzle, he said. “No one has the slightest idea what will work.

The cupboard is bare.”

Education Gap Grows Between Rich and Poor,

Studies Say,

NYT, 9.2.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/10/education/

education-gap-grows-between-rich-and-poor-studies-show.html

The Great Divorce

January 30, 2012

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

I’ll be shocked if there’s another book this year as important

as Charles Murray’s “Coming Apart.” I’ll be shocked if there’s another book that

so compellingly describes the most important trends in American society.

Murray’s basic argument is not new, that America is dividing into a two-caste

society. What’s impressive is the incredible data he produces to illustrate that

trend and deepen our understanding of it.

His story starts in 1963. There was a gap between rich and poor then, but it

wasn’t that big. A house in an upper-crust suburb cost only twice as much as the

average new American home. The tippy-top luxury car, the Cadillac Eldorado

Biarritz, cost about $47,000 in 2010 dollars. That’s pricy, but nowhere near the

price of the top luxury cars today.

More important, the income gaps did not lead to big behavior gaps. Roughly 98

percent of men between the ages of 30 and 49 were in the labor force, upper

class and lower class alike. Only about 3 percent of white kids were born

outside of marriage. The rates were similar, upper class and lower class.

Since then, America has polarized. The word “class” doesn’t even capture the

divide Murray describes. You might say the country has bifurcated into different

social tribes, with a tenuous common culture linking them.

The upper tribe is now segregated from the lower tribe. In 1963, rich people who

lived on the Upper East Side of Manhattan lived close to members of the middle

class. Most adult Manhattanites who lived south of 96th Street back then hadn’t

even completed high school. Today, almost all of Manhattan south of 96th Street

is an upper-tribe enclave.

Today, Murray demonstrates, there is an archipelago of affluent enclaves

clustered around the coastal cities, Chicago, Dallas and so on. If you’re born

into one of them, you will probably go to college with people from one of the

enclaves; you’ll marry someone from one of the enclaves; you’ll go off and live

in one of the enclaves.

Worse, there are vast behavioral gaps between the educated upper tribe (20

percent of the country) and the lower tribe (30 percent of the country). This is

where Murray is at his best, and he’s mostly using data on white Americans, so

the effects of race and other complicating factors don’t come into play.

Roughly 7 percent of the white kids in the upper tribe are born out of wedlock,

compared with roughly 45 percent of the kids in the lower tribe. In the upper

tribe, nearly every man aged 30 to 49 is in the labor force. In the lower tribe,

men in their prime working ages have been steadily dropping out of the labor

force, in good times and bad.

People in the lower tribe are much less likely to get married, less likely to go

to church, less likely to be active in their communities, more likely to watch

TV excessively, more likely to be obese.

Murray’s story contradicts the ideologies of both parties. Republicans claim

that America is threatened by a decadent cultural elite that corrupts regular

Americans, who love God, country and traditional values. That story is false.

The cultural elites live more conservative, traditionalist lives than the

cultural masses.

Democrats claim America is threatened by the financial elite, who hog society’s

resources. But that’s a distraction. The real social gap is between the top 20

percent and the lower 30 percent. The liberal members of the upper tribe latch

onto this top 1 percent narrative because it excuses them from the central role

they themselves are playing in driving inequality and unfairness.

It’s wrong to describe an America in which the salt of the earth common people

are preyed upon by this or that nefarious elite. It’s wrong to tell the familiar

underdog morality tale in which the problems of the masses are caused by the

elites.

The truth is, members of the upper tribe have made themselves phenomenally

productive. They may mimic bohemian manners, but they have returned to 1950s

traditionalist values and practices. They have low divorce rates, arduous work

ethics and strict codes to regulate their kids.

Members of the lower tribe work hard and dream big, but are more removed from

traditional bourgeois norms. They live in disorganized, postmodern neighborhoods

in which it is much harder to be self-disciplined and productive.

I doubt Murray would agree, but we need a National Service Program. We need a

program that would force members of the upper tribe and the lower tribe to live

together, if only for a few years. We need a program in which people from both

tribes work together to spread out the values, practices and institutions that

lead to achievement.

If we could jam the tribes together, we’d have a better elite and a better mass.

The Great Divorce, NYT, 30.1.2012,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/

opinion/brooks-the-great-divorce.html

Putting

Millionaires Before Jobs

November 3,

2011

The New York Times

There’s

nothing partisan about a road or a bridge or an airport; Democrats and

Republicans have voted to spend billions on them for decades and long supported

rebuilding plans in their own states. On Thursday, though, when President

Obama’s plan to spend $60 billion on infrastructure repairs came up for a vote

in the Senate, not a single Republican agreed to break the party’s filibuster.

That’s because the bill would pay for itself with a 0.7 percent surtax on people

making more than $1 million. That would affect about 345,000 taxpayers,

according to Citizens for Tax Justice, adding an average of $13,457 to their

annual tax bills. Protecting that elite group — and hewing to their rigid

antitax vows — was more important to Senate Republicans than the thousands of

construction jobs the bill would have helped create, or the millions of people

who would have used the rebuilt roads, bridges and airports.

Senate Republicans filibustered the president’s full jobs act last month for the

same reasons. And they have vowed to block the individual pieces of that bill

that Democrats are now bringing to the floor. Senate Democrats have also accused

them of opposing any good idea that might put people back to work and rev the

economy a bit before next year’s presidential election.

There is no question that the infrastructure bill would be good for the flagging

economy — and good for the country’s future development. It would directly spend

$50 billion on roads, bridges, airports and mass transit systems, and it would

then provide another $10 billion to an infrastructure bank to encourage

private-sector investment in big public works projects.

Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, a Republican of Texas, co-sponsored an

infrastructure-bank bill in March, and other Republicans have supported similar

efforts over the years. But the Republicans’ determination to stick to an

antitax pledge clearly trumps even their own good ideas.

A competing Republican bill, which also failed on Thursday, was cobbled together

in an attempt to make it appear as if the party has equally valid ideas on job

creation and rebuilding. It would have extended the existing highway and public

transportation financing for two years, paying for it with a $40 billion cut to

other domestic programs. Republican senators also threw in a provision that

would block the Environmental Protection Agency from issuing new clean air

rules. Only in the fevered dreams of corporate polluters could that help create

jobs.

Mitch McConnell, the Senate Republican leader, bitterly accused Democrats of

designing their infrastructure bill to fail by paying for it with a

millionaire’s tax, as if his party’s intransigence was so indomitable that

daring to challenge it is somehow underhanded.

The only good news is that the Democrats aren’t going to stop. There are many

more jobs bills to come, including extension of unemployment insurance and the

payroll-tax cut. If Republicans are so proud of blocking all progress, they will

have to keep doing it over and over again, testing the patience of American

voters.

Putting Millionaires Before Jobs, NYT, 3.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/opinion/

the-senate-puts-millionaires-before-jobs.html

Oligarchy, American Style

November 3,

2011

The New York Times

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Inequality

is back in the news, largely thanks to Occupy Wall Street, but with an assist

from the Congressional Budget Office. And you know what that means: It’s time to

roll out the obfuscators!

Anyone who has tracked this issue over time knows what I mean. Whenever growing

income disparities threaten to come into focus, a reliable set of defenders

tries to bring back the blur. Think tanks put out reports claiming that

inequality isn’t really rising, or that it doesn’t matter. Pundits try to put a

more benign face on the phenomenon, claiming that it’s not really the wealthy

few versus the rest, it’s the educated versus the less educated.

So what you need to know is that all of these claims are basically attempts to

obscure the stark reality: We have a society in which money is increasingly

concentrated in the hands of a few people, and in which that concentration of

income and wealth threatens to make us a democracy in name only.

The budget office laid out some of that stark reality in a recent report, which

documented a sharp decline in the share of total income going to lower- and

middle-income Americans. We still like to think of ourselves as a middle-class

country. But with the bottom 80 percent of households now receiving less than

half of total income, that’s a vision increasingly at odds with reality.

In response, the usual suspects have rolled out some familiar arguments: the

data are flawed (they aren’t); the rich are an ever-changing group (not so); and

so on. The most popular argument right now seems, however, to be the claim that

we may not be a middle-class society, but we’re still an upper-middle-class

society, in which a broad class of highly educated workers, who have the skills

to compete in the modern world, is doing very well.

It’s a nice story, and a lot less disturbing than the picture of a nation in

which a much smaller group of rich people is becoming increasingly dominant. But

it’s not true.

Workers with college degrees have indeed, on average, done better than workers

without, and the gap has generally widened over time. But highly educated

Americans have by no means been immune to income stagnation and growing economic

insecurity. Wage gains for most college-educated workers have been unimpressive

(and nonexistent since 2000), while even the well-educated can no longer count

on getting jobs with good benefits. In particular, these days workers with a

college degree but no further degrees are less likely to get workplace health

coverage than workers with only a high school degree were in 1979.

So who is getting the big gains? A very small, wealthy minority.

The budget office report tells us that essentially all of the upward

redistribution of income away from the bottom 80 percent has gone to the

highest-income 1 percent of Americans. That is, the protesters who portray

themselves as representing the interests of the 99 percent have it basically

right, and the pundits solemnly assuring them that it’s really about education,

not the gains of a small elite, have it completely wrong.

If anything, the protesters are setting the cutoff too low. The recent budget

office report doesn’t look inside the top 1 percent, but an earlier report,

which only went up to 2005, found that almost two-thirds of the rising share of

the top percentile in income actually went to the top 0.1 percent — the richest

thousandth of Americans, who saw their real incomes rise more than 400 percent

over the period from 1979 to 2005.

Who’s in that top 0.1 percent? Are they heroic entrepreneurs creating jobs? No,

for the most part, they’re corporate executives. Recent research shows that

around 60 percent of the top 0.1 percent either are executives in nonfinancial

companies or make their money in finance, i.e., Wall Street broadly defined. Add

in lawyers and people in real estate, and we’re talking about more than 70

percent of the lucky one-thousandth.

But why does this growing concentration of income and wealth in a few hands

matter? Part of the answer is that rising inequality has meant a nation in which

most families don’t share fully in economic growth. Another part of the answer

is that once you realize just how much richer the rich have become, the argument

that higher taxes on high incomes should be part of any long-run budget deal

becomes a lot more compelling.

The larger answer, however, is that extreme concentration of income is

incompatible with real democracy. Can anyone seriously deny that our political

system is being warped by the influence of big money, and that the warping is

getting worse as the wealth of a few grows ever larger?

Some pundits are still trying to dismiss concerns about rising inequality as

somehow foolish. But the truth is that the whole nature of our society is at

stake.

Oligarchy, American Style, NYT, 3.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/opinion/oligarchy-american-style.html

The Angry Rich

September 19, 2010

The New York imes

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Anger is sweeping America. True, this white-hot rage is a minority

phenomenon, not something that characterizes most of our fellow citizens. But

the angry minority is angry indeed, consisting of people who feel that things to

which they are entitled are being taken away. And they’re out for revenge.

No, I’m not talking about the Tea Partiers. I’m talking about the rich.

These are terrible times for many people in this country. Poverty, especially

acute poverty, has soared in the economic slump; millions of people have lost

their homes. Young people can’t find jobs; laid-off 50-somethings fear that

they’ll never work again.

Yet if you want to find real political rage — the kind of rage that makes people

compare President Obama to Hitler, or accuse him of treason — you won’t find it

among these suffering Americans. You’ll find it instead among the very

privileged, people who don’t have to worry about losing their jobs, their homes,

or their health insurance, but who are outraged, outraged, at the thought of

paying modestly higher taxes.

The rage of the rich has been building ever since Mr. Obama took office. At

first, however, it was largely confined to Wall Street. Thus when New York

magazine published an article titled “The Wail Of the 1%,” it was talking about

financial wheeler-dealers whose firms had been bailed out with taxpayer funds,

but were furious at suggestions that the price of these bailouts should include

temporary limits on bonuses. When the billionaire Stephen Schwarzman compared an

Obama proposal to the Nazi invasion of Poland, the proposal in question would

have closed a tax loophole that specifically benefits fund managers like him.

Now, however, as decision time looms for the fate of the Bush tax cuts — will

top tax rates go back to Clinton-era levels? — the rage of the rich has

broadened, and also in some ways changed its character.

For one thing, craziness has gone mainstream. It’s one thing when a billionaire

rants at a dinner event. It’s another when Forbes magazine runs a cover story

alleging that the president of the United States is deliberately trying to bring

America down as part of his Kenyan, “anticolonialist” agenda, that “the U.S. is

being ruled according to the dreams of a Luo tribesman of the 1950s.” When it

comes to defending the interests of the rich, it seems, the normal rules of

civilized (and rational) discourse no longer apply.

At the same time, self-pity among the privileged has become acceptable, even

fashionable.

Tax-cut advocates used to pretend that they were mainly concerned about helping

typical American families. Even tax breaks for the rich were justified in terms

of trickle-down economics, the claim that lower taxes at the top would make the

economy stronger for everyone.

These days, however, tax-cutters are hardly even trying to make the trickle-down

case. Yes, Republicans are pushing the line that raising taxes at the top would

hurt small businesses, but their hearts don’t really seem in it. Instead, it has

become common to hear vehement denials that people making $400,000 or $500,000 a

year are rich. I mean, look at the expenses of people in that income class — the

property taxes they have to pay on their expensive houses, the cost of sending

their kids to elite private schools, and so on. Why, they can barely make ends

meet.

And among the undeniably rich, a belligerent sense of entitlement has taken

hold: it’s their money, and they have the right to keep it. “Taxes are what we

pay for civilized society,” said Oliver Wendell Holmes — but that was a long

time ago.

The spectacle of high-income Americans, the world’s luckiest people, wallowing

in self-pity and self-righteousness would be funny, except for one thing: they

may well get their way. Never mind the $700 billion price tag for extending the

high-end tax breaks: virtually all Republicans and some Democrats are rushing to

the aid of the oppressed affluent.

You see, the rich are different from you and me: they have more influence. It’s

partly a matter of campaign contributions, but it’s also a matter of social

pressure, since politicians spend a lot of time hanging out with the wealthy. So

when the rich face the prospect of paying an extra 3 or 4 percent of their

income in taxes, politicians feel their pain — feel it much more acutely, it’s

clear, than they feel the pain of families who are losing their jobs, their

houses, and their hopes.

And when the tax fight is over, one way or another, you can be sure that the

people currently defending the incomes of the elite will go back to demanding

cuts in Social Security and aid to the unemployed. America must make hard

choices, they’ll say; we all have to be willing to make sacrifices.

But when they say “we,” they mean “you.” Sacrifice is for the little people.

The Angry Rich, NYT,

19.9.2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/20/

opinion/20krugman.html

Baker who won £9m on lottery

dies penniless, five years on

Keith Gough spent much of his winnings

on racehorses, fast cars and an executive

box

at Aston Villa

The Guardian

Jenny Percival

Saturday 3 April 2010

This article appeared on p9

of the Main section section of the Guardian

on

Saturday 3 April 2010.

It was published on guardian.co.uk at 01.32 BST

on Saturday 3 April 2010.

A former baker who claimed that winning £9m on the lottery ruined his life,

leaving him penniless, alone and alcoholic, has died of a suspected heart

attack.

Keith Gough, 58, won the jackpot with his wife Louise in June 2005, but spent

much of his winnings on racehorses, fast cars and an executive box at Aston

Villa. He died at the Princess Royal hospital in Telford, Shropshire. It is

believed he suffered a heart attack.

Two years after his win, Gough split from his wife of 25 years and began

drinking heavily. He then reportedly checked into the Priory rehabilitation

clinic in Birmingham for treatment.

He said he slept in the spare room of his nephew's house and spent most of his

time indoors, only venturing out for long walks alone in the Shropshire

countryside.

"My life was brilliant. But the lottery has ruined everything. What's the point

of having money when it sends you to bed crying?" he told the News of the World

last year. "Now when I see someone going in to a newsagent I advise them not to

buy a lottery ticket."

According to the paper the win made him a target for conmen, one of whom cheated

him out of £700,000.

Gough, who lived in Brignorth, Shropshire, at the time of his win, said he and

his wife, a secretary, had been very much in love and looking forward to

retirement.

John Homer, who owns a newsagents in Broseley, Shropshire, said yesterday that

he still remembered when "Goughie" bought his winning ticket. Homer, 65, said:

"It was a Wednesday and a rollover from the previous Saturday. It all went

downhill from there. He and his wife split. He did have a drink problem and it

got progressively worse."

He added: "It's very sad because it should have made him a very happy man, but

he didn't get the best out of it. You never expected any sorrow or problems, but

he must have had some, although he never spoke about them to me."

Gough, who was driving a T-registered Skoda at the time of the win, said at the

time he had to "pinch himself". "I have never had any dreams come true before

and now I suppose I don't have to have any dreams."

Baker who won £9m on

lottery dies penniless, five years on,

G, 3.4.2010,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/apr/03/baker-won-lottery-dies-penniless

Unequal Britain: richest 10%

are now 100 times better off

than

the poorest

• 1980s income gap still not plugged, say analysts

• Brown says equality panel report a 'sobering' read

• Datablog: get the numbers behind this story

Wednesday 27 January 2010

08.54 GMT

Guardian.co.uk

Amelia Gentleman and Hélène Mulholland

This article was published

on guardian.co.uk at 08.54 GMT

on Wednesday 27

January 2010.

It was last modified at 08.57 GMT

on Wednesday 27 January 2010.

A detailed and startling analysis of how unequal Britain has become offers a

snapshot of an increasingly divided nation where the richest 10% of the

population are more than 100 times as wealthy as the poorest 10% of society.

Gordon Brown described the paper, published today, as "sobering", saying: "The

report illustrates starkly that despite a levelling-off of inequality in the

last decade we still have much further to go."

The report, An Anatomy of Economic Inequality in the UK, scrutinises the degree

to which the country has become more unequal over the past 30 years. Much of it

will make uncomfortable reading for the Labour government, although the paper

indicates that considerable responsibility lies with the Tories, who presided

over the dramatic divisions of the 1980s and early 1990s.

Researchers analyse inequality according to a number of measures; one indicates

that by 2007-8 Britain had reached the highest level of income inequality since

soon after the second world war.

The new findings show that the household wealth of the top 10% of the population

stands at £853,000 and more – over 100 times higher than the wealth of the

poorest 10%, which is £8,800 or below (a sum including cars and other

possessions).

When the highest-paid workers, such as bankers and chief executives, are put

into the equation, the division in wealth is even more stark, with individuals

in the top 1% of the population each possessing total household wealth of £2.6m

or more.