|

Vocapedia >

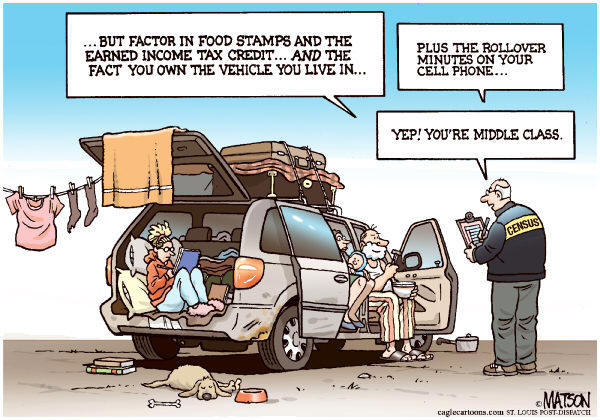

Economy > The middle

class

RJ Matson

Editorial cartoon

The St. Louis Post Dispatch

Cagle

18 July 2011

UK > class in Britain

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/04/

world/europe/multiplying-the-old-divisions-of-class-in-britain.html

middle class UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/dec/12/

british-middle-class-young-people-class-home-ownership-job-security

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/24/

middle-class-living-standards

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/aug/02/

london-inequality-house-prices

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/oct/20/

britishidentity.socialexclusion

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/oct/20/

britishidentity.socialexclusion1

middle class

USA

https://www.npr.org/series/485129365/the-new-middle

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/06/

us/economic-segregation-income.html

https://www.npr.org/2020/08/18/

903660865/making-the-middle-class-great-again

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/16/

648112378/she-thought-her-family-was-middle-class-not-broke-in-the-richest-country-on-eart

http://www.npr.org/2017/01/14/

509497278/a-trump-swing-voter-looks-ahead

http://www.npr.org/2016/07/07/

484941939/a-portrait-of-americas-middle-class-by-the-numbers

http://www.npr.org/2016/07/05/

481571379/a-brief-history-of-americas-middle-class

http://www.npr.org/2016/06/22/

482135775/what-its-like-to-be-a-part-of-the-vanishing-middle-class

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/13/

upshot/falling-middle-class.html

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/24/

475432149/could-you-come-up-with-400-if-disaster-struck

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/10/

473702974/hanging-on-a-pressured-middle-class-in-economic-recovery

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/02/

opinion/campaign-stops/how-both-parties-lost-the-white-middle-class.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/28/

opinion/campaign-stops/250000-a-year-is-not-middle-class.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/12/09/

459087477/the-tipping-point-most-americans-no-longer-are-middle-class

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/11/

business/economy/middle-class-but-feeling-economically-insecure.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/26/

upshot/what-is-middle-class-economics.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/18/us/

president-obama-will-seek-to-reduce-taxes-for-middle-class.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/23/

upshot/the-american-middle-class-is-no-longer-the-worlds-richest.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/15/

business/more-renters-find-30-affordability-ratio-unattainable.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/02/

opinion/edsall-is-the-american-middle-class-losing-out-to-china-and-india.html

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/19/

the-middle-class-gets-wise/

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/

opinion/blow-the-morose-middle-class.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/10/us/politics/

in-state-of-the-union-address-obama-will-lay-out-agenda-

focused-on-the-middle-class.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/12/04/

in-reducing-deficit-can-the-middle-class-be-spared

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/04/

opinion/sunday/jobs-will-follow-a-strengthening-of-the-middle-class.html

middle-class decline

USA

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/23/

a-closer-look-at-middle-class-decline/

black middle class

USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/09/02/492251653/

for-the-black-middle-class-housing-crisis-and-history-collude-to-dash-dreams

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/25/

upshot/middle-class-black-families-in-low-income-neighborhoods.html

Middle-Class Black

Families,

in Low-Income Neighborhoods

NYT JUNE 24, 2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/25/

upshot/middle-class-black-families-in-low-income-neighborhoods.html

‘middle-class

economics’ USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/26/

upshot/what-is-middle-class-economics.html

lower-middle-class people

people who are not

rich USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/12/

your-money/start-ups-offer-financial-advice-to-people-who-arent-rich.html

standard of living

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/24/us/

politics/race-for-president-leaves-income-slump-in-shadows.html

income slump / slowdown

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/24/us/

politics/race-for-president-leaves-income-slump-in-shadows.html

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/21/

globalization-and-the-income-slowdown/

gentrify USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/22/

opinion/l22brooks.html

gentrification UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/aug/02/

london-inequality-house-prices

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/video/2013/aug/02/

alex-wheatle-gentrification-brixton-video

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/dec/12/

new-york-brooklyn-williamsburg-gentrification

RJ Matson

cartoon

Cagle

The St. Louis Post Dispatch

9 November 2011

Corpus of news articles

Economy > The middle class

The

Middle-Class Agenda

December

19, 2011

The New York Times

Earlier

this month, President Obama delivered his first unabashed 2012 campaign speech.

Unlike his opponents, Mr. Obama acknowledged the ravages of income equality, the

hollowing out of the American middle class. There is no hyperbole in the urgency

he conveyed about “a make-or-break moment for the middle class, and for all

those who are fighting to get into the middle class.”

The challenge for Mr. Obama is to translate the plight of the middle class into

an agenda for broad prosperity. Congress’s inability to cleanly extend even

emergency measures though 2012 — including the temporary payroll tax cut and

federal unemployment benefits — underscores the difficulty. The alternative is

continued decline.

Recent government data show that 100 million Americans, or about one in three,

are living in poverty or very close to it. Of 13.3 million unemployed Americans

now searching for work, 5.7 million have been looking for more than six months,

while millions more have given up altogether. Even a job is no guarantee of

middle-class security. The real median income of working-age households has

declined, from $61,600 in 2000 to $55,300 in 2010 — the result of abysmally slow

job growth even before the onset of the recession.

Economic growth alone, even if it accelerated, would not be enough to restore

the middle class. Mr. Obama refuted the Republican notion that market forces

alone can ensure broad prosperity, when the economic health of American families

also depends on government action.

It was a speech that called out for a plan. Here are the elements that matter

most:

CREATING

GOOD JOBS Despite Republican obstructionism, Mr. Obama must continue to offer

stimulus bills that include spending for public works, high-tech manufacturing

and an infrastructure bank. He must stress that obstruction costs jobs — the

bill recently filibustered by Republicans would have created an estimated 1.9

million jobs in 2012. The Republican stance also endangers future prosperity by

denying needed infrastructure upgrades and making it likely that international

competitors will outstrip America in jobs and technology.

In particular, Mr. Obama needs to debunk the notion that job creation is at odds

with environmental protection. Republicans have portrayed opposition to the

Keystone XL oil pipeline as a job killer. The truth is, oil addiction and the

failure to invest in new energy sources will be far bigger job killers. What’s

needed is a plan to create millions of clean energy jobs and to link those jobs

to workers in fossil fuel industries who otherwise would be displaced. The

climate bill that died in 2010 would have begun that transformation; the need to

try again only becomes more pressing with each passing year.

At the same time, Mr. Obama cannot ignore that most of the fast-growing

occupations in America are lower-paying service jobs, like home health care and

food service, in which it’s all but impossible to make a living. To lift wages

requires generous tax credits for low earners, a higher minimum wage, and

guaranteed health care so that wages are not consumed by medical costs. Job

training efforts must also focus on the service sector, helping to build

so-called career ladders, say, from home health aid to licensed vocational

nurse.

STOPPING

FORECLOSURES In his Kansas speech, Mr. Obama said banks “should be working to

keep responsible homeowners in their homes.” That’s too weak. The banks have

never made an all-out effort to help homeowners and unless compelled to do so,

they never will, because, in many cases, they can make more by foreclosing

rather than by modifying troubled loans.

Federal agencies can keep working with some state attorneys general and try to

settle with banks over foreclosure abuses in exchange for a commitment from them

to modify some $20 billion worth of troubled loans, or they can conduct a

thorough federal investigation into the banks’ conduct during the mortgage

bubble, looking for a far bigger settlement. The market is beset with $700

billion of negative equity; potential bank abuses are unexplored; the public is

demanding accountability. Mr. Obama should opt for a thorough federal inquiry.

In the meantime, an antiforeclosure plan that is up to the scale of the problem

would include unrelenting political pressure for principal write-downs of

underwater loans, expanded refinancings for borrowers in high-rate loans, and

forbearance for unemployed homeowners.

REGULATING THE BANKS Mr. Obama said banks are fighting the Dodd-Frank reform

“every inch of the way.”

The question is what he will do to fight back. A good start would be for him to

tell the American public whether the law is capable of performing as intended.

Is he confident that a major bank on the verge of failure could be successfully

dismantled? Is he sure that risky bank trading will be sufficiently curtailed?

If he is not confident that the law can work as intended, he must ensure better

implementation or call for a revamp of the statute itself.

He can also personally advance specific Dodd-Frank provisions. Republicans are

intent on destroying the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Mr. Obama

should try to recess appoint his nominee to lead the bureau, Richard Cordray,

whom Republicans recently filibustered. Mr. Obama must make clear that he

supports a strong Dodd-Frank disclosure rule on the ratio of the pay of chief

executives to that of rank-and-file employees. Such disclosure is crucial to

changing the corporate norms that have allowed for unjustifiably vast pay

discrepancies.

RAISING

TAXES, REDUCING THE DEFICIT Tax reform is essential. But there is no way to

build public consensus for broad reform without first reversing the lavish tax

breaks for the rich. In addition to letting the high-end Bush-era tax cuts

expire at the end of 2012, Mr. Obama could call for all forms of income to be

taxed at the same rates, rather than allowing lower rates for investment income,

which flows mostly to wealthy Americans. Income tax rates also need to be

adjusted at the top of the scale, so that the affluent, say, couples with

taxable income of $400,000 a year, are not paying the same top rate as

multimillionaires.

Mr. Obama should also drop his opposition to a financial transactions tax. That

stance may have made sense when the banks were reeling from the financial

crisis, but it is now at odds with a stated desire to rein in the financial

sector and raise needed revenue.

Mr. Obama has more than established his willingness to cut the deficit, agreeing

to spending cuts that, in fact, are too deep for the weak economy. Now he needs

to dominate the deficit debate, not by trying to meet Republican demands for

ever more spending cuts, but by explaining that more cuts would undermine the

recovery. In the near term, high-end tax increases are a better way to control

the deficit. They are less of a drag on economic activity than broad tax

increases or federal spending cuts.

More jobs. Fewer foreclosures. Less financial risk. Progressive taxation. Those

policies will give the middle class a fighting chance. But the list is not

exhaustive. The pillars of a healthy middle class also include public education,

Social Security, unions, child care, affirmative action and, not least, campaign

finance reform, since inequality is reinforced by the political power of the

wealthy.

The Middle-Class Agenda,

NYT,

19.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/20/

opinion/the-middle-class-agenda.html

The

Poor, the Near Poor and You

November

23, 2011

The New York Times

What is

it like to be poor? Thankfully, most Americans do not know, at least not

firsthand. And times are tough for the middle class. But everyone needs to

recognize a chilling reality: One in three Americans — 100 million people — is

either poor or perilously close to it.

The Times’s Jason DeParle, Robert Gebeloff and Sabrina Tavernise reported

recently on Census data showing that 49.1 million Americans are below the

poverty line — in general, $24,343 for a family of four. An additional 51

million are in the next category, which they termed “near poor” — with incomes

less than 50 percent above the poverty line.

As for all of that inspirational, up-by-their-bootstrap talk you hear on the

Republican campaign trail, over half of the near poor in the new tally actually

fell into that group from higher income levels as their resources were sapped by

medical expenses, taxes, work-related costs and other unavoidable outlays.

The worst downturn since the Great Depression is only part of the problem.

Before that, living standards were already being eroded by stagnating wages and

tax and economic policies that favored the wealthy.

Conservative politicians and analysts are spouting their usual denial. Gov. Rick

Perry and Representative Michele Bachmann have called for taxing the poor and

near poor more heavily, on the false grounds that they have been getting a free

ride. In fact, low-income workers do pay up, if not in federal income taxes,

then in payroll taxes and state and local taxes.

Asked about the new census data, Robert Rector, an analyst at the conservative

Heritage Foundation told The Times that the “emotionally charged terms ‘poor’ or

‘near poor’ clearly suggest to most people a level of material hardship that

doesn’t exist.” Heritage has its own, very different ranking system, based on

households’ “amenities.” According to that, the typical poor household has

roughly 14 of 30 amenities. In other words, how hard can things be if you have a

refrigerator, air-conditioner, coffee maker, cellphone, and other stuff?

The rankings ignore the fact that many of these are requisites of modern life

and that things increasingly out of reach for the poor and near poor —

education, health care, child care, housing and utilities — are the true

determinants of a good, upwardly mobile life.

Government surveys analyzed by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

indicate that in 2010, just over half of the country’s nearly 17 million poor

children, lived in households that reported at least one of four major

hardships: hunger, overcrowding, failure to pay the rent or mortgage on time or

failure to seek needed medical care. A good education is also increasingly out

of reach. A study by Martha Bailey, an economics professor at the University of

Michigan, showed that the difference in college-graduation rates between the

rich and poor has widened by more than 50 percent since the 1990s.

There is also a growing out-of-sight-out-of-mind problem. A study, by Sean

Reardon, a sociologist at Stanford, shows that Americans are increasingly living

in areas that are either poor or affluent. The isolation of the prosperous, he

said, threatens their support for public schools, parks, mass transit and other

investments that benefit broader society.

The poor do without and the near poor, at best, live from paycheck to paycheck.

Most Americans don’t know what that is like, but unless the nation reverses

direction, more are going to find out.

The Poor, the Near Poor and You,

NYT, 23.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/24/

opinion/the-poor-the-near-poor-and-you.html

The

Limping Middle Class

September

3, 2011

The New York Times

By ROBERT B. REICH

Robert B.

Reich is the former secretary of labor, a professor at the University of

California, Berkeley, and the author of “Aftershock: The Next Economy and

America’s Future.”

THE 5 percent of Americans with the highest incomes now account for 37 percent

of all consumer purchases, according to the latest research from Moody’s

Analytics. That should come as no surprise. Our society has become more and more

unequal.

When so much income goes to the top, the middle class doesn’t have enough

purchasing power to keep the economy going without sinking ever more deeply into

debt — which, as we’ve seen, ends badly. An economy so dependent on the spending

of a few is also prone to great booms and busts. The rich splurge and speculate

when their savings are doing well. But when the values of their assets tumble,

they pull back. That can lead to wild gyrations. Sound familiar?

The economy won’t really bounce back until America’s surge toward inequality is

reversed. Even if by some miracle President Obama gets support for a second big

stimulus while Ben S. Bernanke’s Fed keeps interest rates near zero, neither

will do the trick without a middle class capable of spending. Pump-priming works

only when a well contains enough water.

Look back over the last hundred years and you’ll see the pattern. During periods

when the very rich took home a much smaller proportion of total income — as in

the Great Prosperity between 1947 and 1977 — the nation as a whole grew faster

and median wages surged. We created a virtuous cycle in which an ever growing

middle class had the ability to consume more goods and services, which created

more and better jobs, thereby stoking demand. The rising tide did in fact lift

all boats.

During periods when the very rich took home a larger proportion — as between

1918 and 1933, and in the Great Regression from 1981 to the present day — growth

slowed, median wages stagnated and we suffered giant downturns. It’s no mere

coincidence that over the last century the top earners’ share of the nation’s

total income peaked in 1928 and 2007 — the two years just preceding the biggest

downturns.

Starting in the late 1970s, the middle class began to weaken. Although

productivity continued to grow and the economy continued to expand, wages began

flattening in the 1970s because new technologies — container ships, satellite

communications, eventually computers and the Internet — started to undermine any

American job that could be automated or done more cheaply abroad. The same

technologies bestowed ever larger rewards on people who could use them to

innovate and solve problems. Some were product entrepreneurs; a growing number

were financial entrepreneurs. The pay of graduates of prestigious colleges and

M.B.A. programs — the “talent” who reached the pinnacles of power in executive

suites and on Wall Street — soared.

The middle class nonetheless continued to spend, at first enabled by the flow of

women into the work force. (In the 1960s only 12 percent of married women with

young children were working for pay; by the late 1990s, 55 percent were.) When

that way of life stopped generating enough income, Americans went deeper into

debt. From the late 1990s to 2007, the typical household debt grew by a third.

As long as housing values continued to rise it seemed a painless way to get

additional money.

Eventually, of course, the bubble burst. That ended the middle class’s

remarkable ability to keep spending in the face of near stagnant wages. The

puzzle is why so little has been done in the last 40 years to help deal with the

subversion of the economic power of the middle class. With the continued gains

from economic growth, the nation could have enabled more people to become

problem solvers and innovators — through early childhood education, better

public schools, expanded access to higher education and more efficient public

transportation.

We might have enlarged safety nets — by having unemployment insurance cover

part-time work, by giving transition assistance to move to new jobs in new

locations, by creating insurance for communities that lost a major employer. And

we could have made Medicare available to anyone.

Big companies could have been required to pay severance to American workers they

let go and train them for new jobs. The minimum wage could have been pegged at

half the median wage, and we could have insisted that the foreign nations we

trade with do the same, so that all citizens could share in gains from trade.

We could have raised taxes on the rich and cut them for poorer Americans.

But starting in the late 1970s, and with increasing fervor over the next three

decades, government did just the opposite. It deregulated and privatized. It cut

spending on infrastructure as a percentage of the national economy and shifted

more of the costs of public higher education to families. It shredded safety

nets. (Only 27 percent of the unemployed are covered by unemployment insurance.)

And it allowed companies to bust unions and threaten employees who tried to

organize. Fewer than 8 percent of private-sector workers are unionized.

More generally, it stood by as big American companies became global companies

with no more loyalty to the United States than a GPS satellite. Meanwhile, the

top income tax rate was halved to 35 percent and many of the nation’s richest

were allowed to treat their income as capital gains subject to no more than 15

percent tax. Inheritance taxes that affected only the topmost 1.5 percent of

earners were sliced. Yet at the same time sales and payroll taxes — both taking

a bigger chunk out of modest paychecks — were increased.

Most telling of all, Washington deregulated Wall Street while insuring it

against major losses. In so doing, it allowed finance — which until then had

been the servant of American industry — to become its master, demanding

short-term profits over long-term growth and raking in an ever larger portion of

the nation’s profits. By 2007, financial companies accounted for over 40 percent

of American corporate profits and almost as great a percentage of pay, up from

10 percent during the Great Prosperity.

Some say the regressive lurch occurred because Americans lost confidence in

government. But this argument has cause and effect backward. The tax revolts

that thundered across America starting in the late 1970s were not so much

ideological revolts against government — Americans still wanted all the

government services they had before, and then some — as against paying more

taxes on incomes that had stagnated. Inevitably, government services

deteriorated and government deficits exploded, confirming the public’s growing

cynicism about government’s doing anything right.

Some say we couldn’t have reversed the consequences of globalization and

technological change. Yet the experiences of other nations, like Germany,

suggest otherwise. Germany has grown faster than the United States for the last

15 years, and the gains have been more widely spread. While Americans’ average

hourly pay has risen only 6 percent since 1985, adjusted for inflation, German

workers’ pay has risen almost 30 percent. At the same time, the top 1 percent of

German households now take home about 11 percent of all income — about the same

as in 1970. And although in the last months Germany has been hit by the debt

crisis of its neighbors, its unemployment is still below where it was when the

financial crisis started in 2007.

How has Germany done it? Mainly by focusing like a laser on education (German

math scores continue to extend their lead over American), and by maintaining

strong labor unions.

THE real reason for America’s Great Regression was political. As income and

wealth became more concentrated in fewer hands, American politics reverted to

what Marriner S. Eccles, a former chairman of the Federal Reserve, described in

the 1920s, when people “with great economic power had an undue influence in

making the rules of the economic game.” With hefty campaign contributions and

platoons of lobbyists and public relations spinners, America’s executive class

has gained lower tax rates while resisting reforms that would spread the gains

from growth.

Yet the rich are now being bitten by their own success. Those at the top would

be better off with a smaller share of a rapidly growing economy than a large

share of one that’s almost dead in the water.

The economy cannot possibly get out of its current doldrums without a strategy

to revive the purchasing power of America’s vast middle class. The spending of

the richest 5 percent alone will not lead to a virtuous cycle of more jobs and

higher living standards. Nor can we rely on exports to fill the gap. It is

impossible for every large economy, including the United States, to become a net

exporter.

Reviving the middle class requires that we reverse the nation’s decades-long

trend toward widening inequality. This is possible notwithstanding the political

power of the executive class. So many people are now being hit by job losses,

sagging incomes and declining home values that Americans could be mobilized.

Moreover, an economy is not a zero-sum game. Even the executive class has an

enlightened self-interest in reversing the trend; just as a rising tide lifts

all boats, the ebbing tide is now threatening to beach many of the yachts. The

question is whether, and when, we will summon the political will. We have

summoned it before in even bleaker times.

As the historian James Truslow Adams defined the American Dream when he coined

the term at the depths of the Great Depression, what we seek is “a land in which

life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone.”

That dream is still within our grasp.

The Limping Middle Class,

NYT,

3.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/04/

opinion/sunday/jobs-will-follow-a-strengthening-of-the-middle-class.html

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia

economy, money, taxes,

housing market, shopping,

jobs, unemployment,

unions, retirement,

debt,

poverty, hunger,

homelessness

industry, energy, commodities

|