|

Vocapedia >

Economy > Poverty > Food

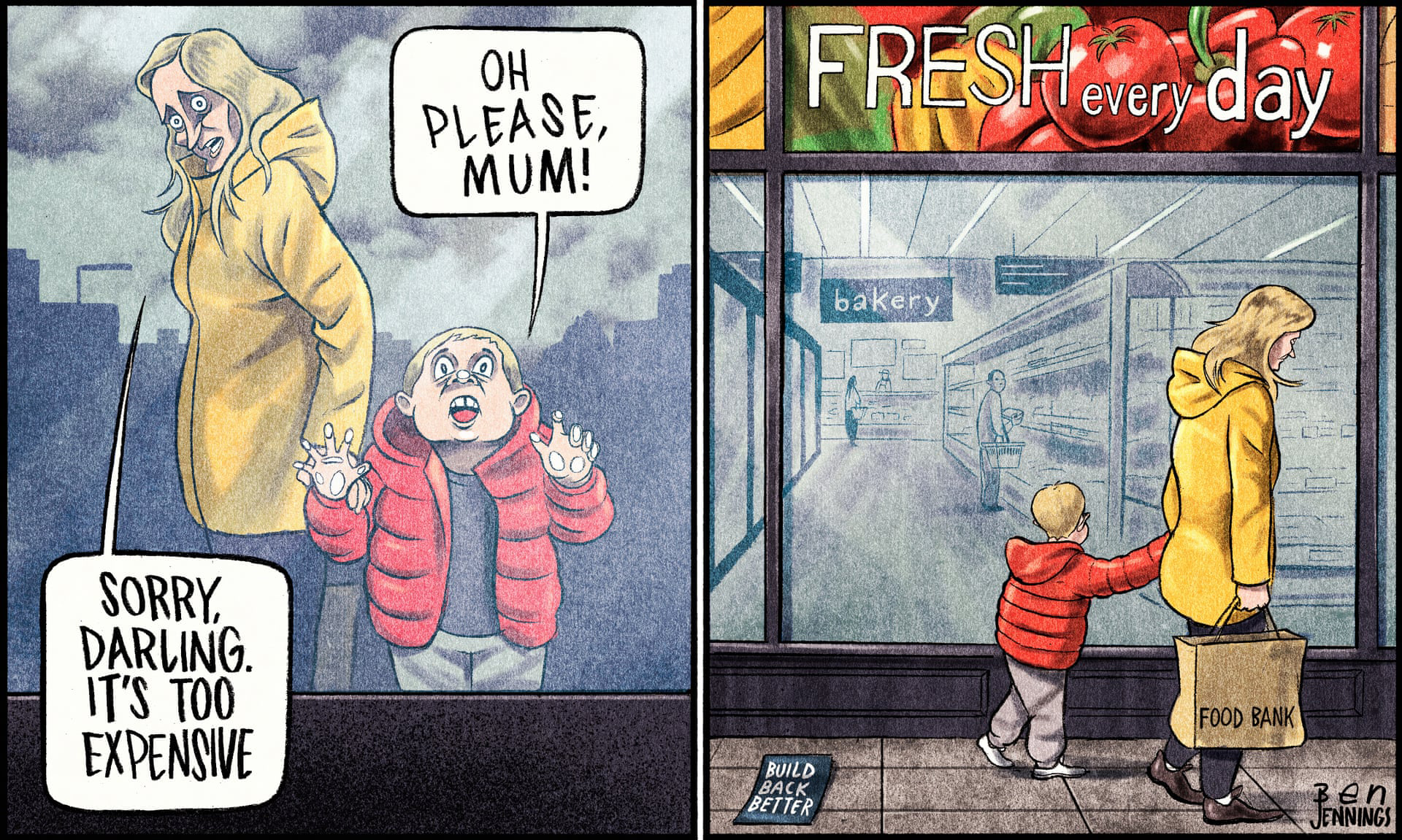

Ben Jennings

on the UK’s cost of living

crisis – cartoon

G

Tue 12 Apr 2022 20.00 BST

Last modified on Wed 27 Apr 2022

14.20 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2022/apr/12/

ben-jennings-on-the-uks-cost-of-living-crisis-cartoon

Related

The Guardian >

Opinion cartoons > Ben Jennings

https://www.theguardian.com/profile/ben-jennings

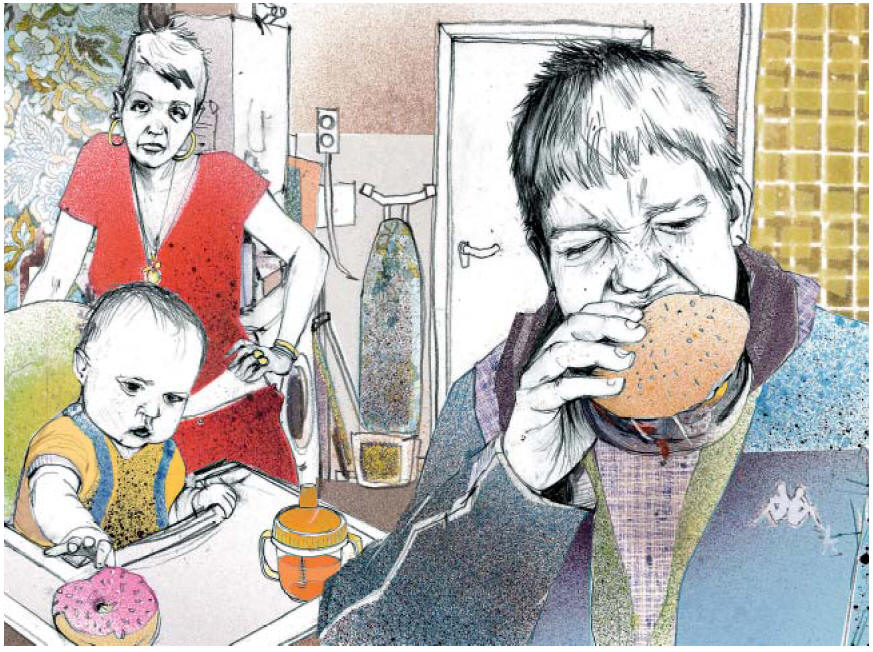

Illustration: Thea Brine

The hunger within

In his latest despatches

from an English

housing estate,

Stewart Dakers describes how,

from junk food diets

to chronic illiteracy and

feckless fathers,

the underclass are trapped

in a near hopeless 'toxic cycle' of

deprivation

G

p. 7

Wednesday January 4, 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/jan/04/

socialexclusion.guardiansocietysupplement

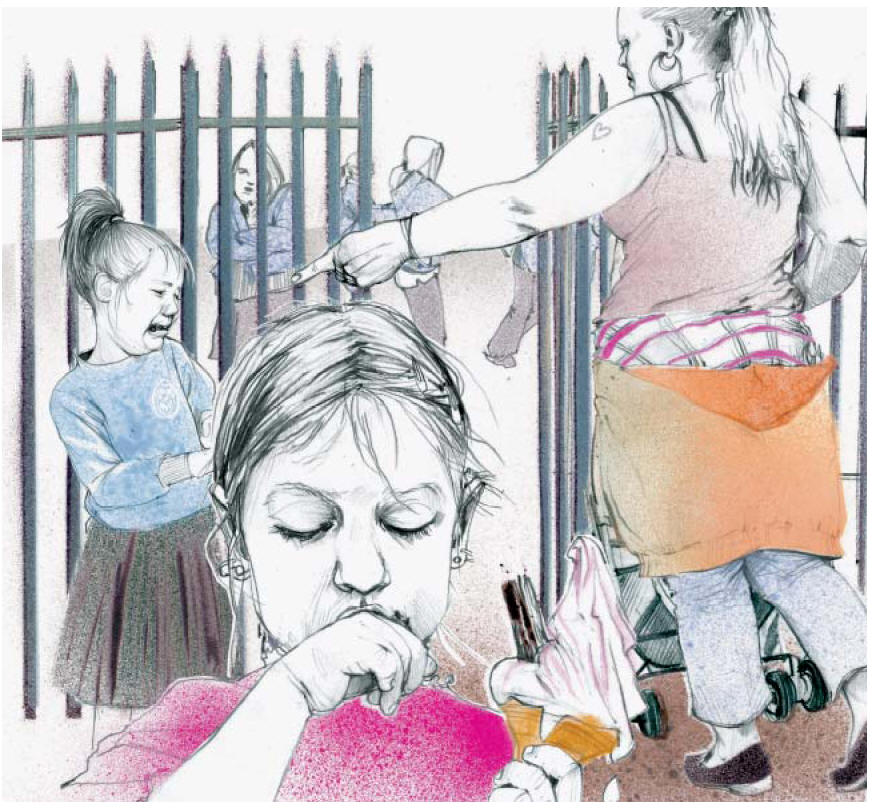

Illustration: Thea Brine

Dog eat dog

In his latest real life dispatches

from an English housing estate

Stewart Dakers

finds abuse, violence and bullying

— but nothing that hasn’t already been done

by those who rule over us in the

corridors of power

The Guardian Society 1

p. 3

15

March 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/mar/15/

communities.socialexclusion

Illustration: Thea Brine

Growing pains

Where did it all go wrong for Louise?

Once a cheeky, freckle-faced girl,

she is

now a prostitute addicted to crack cocaine - and is still only 23.

Her friend, author Bernard Hare, pieces together her

harrowing life

The Guardian Society

p. 3 Wednesday March 29, 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/mar/29/

crime.politicsphilosophyandsociety

eat

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/dec/02/

thats-me-paul-pryde-moss-side-manchester

https://www.theguardian.com/business/gallery/2008/sep/23/

creditcrunch.marketturmoil?picture=337937358

eat

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/05/

920314166/millions-of-americans-cant-afford-enough-to-eat-

as-pandemic-relief-stalls-in-d-c

diet

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2008/oct/01/

foodanddrink.oliver

food

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/dec/02/

thats-me-paul-pryde-moss-side-manchester

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/nov/18/

redundancy-family-food-quality-issue

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/jan/17/

eating-heating-furniture-cold-weather

food

USA

https://www.npr.org/2023/06/02/

1179633624/snap-food-assistance-work-requirements-congress-debt-ceiling

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/11/28/

783066219/food-pharmacies-in-clinics-when-the-diagnosis-is-chronic-hunger

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/25/

opinion/more-hunger-for-the-poorest-americans.html

food assistance

https://www.npr.org/2023/06/02/

1179633624/snap-food-assistance-work-requirements-congress-debt-ceiling

food insecurity

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/10/26/

1208760054/food-insecurity-families-struggle-hunger-poverty

https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/12/14/

946420784/u-s-faces-food-insecurity-crisis-

as-several-federal-aid-programs-set-to-run-out-

https://www.npr.org/2020/10/05/

920314166/millions-of-americans-cant-afford-enough-to-eat-

as-pandemic-relief-stalls-in-d-c

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/

912486921/food-insecurity-in-the-u-s-by-the-numbers

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/

913612554/a-crisis-within-a-crisis-food-insecurity-and-covid-19

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/

917326212/in-affluent-maryland-county-pandemic-exacerbates-food-insecurity

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/11/28/

783066219/food-pharmacies-in-clinics-when-the-diagnosis-is-chronic-hunger

food

insecure USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/

914018048/for-one-food-insecure-family-the-pandemic-leaves-no-wiggle-room

feed

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/

health/coronavirus-hunger-unemployment.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/

nyregion/food-bank-drivers-coronavirus-ny.html

feed the needy

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/26/us/

ellen-turner-dies-at-87-opened-kitchen-to-feed-the-needy-of-knoxville.html

Feeding America USA

https://www.feedingamerica.org/

staples

grocery / food budget

USA

https://www.npr.org/2019/11/29/

783029904/a-mother-and-daughter-on-homelessness-humility-

and-a-6-a-week-grocery-budget

basic needs

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/money/2014/jun/30/

couple-two-children-earn-basic-needs

food prices

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/21/

tesco-boss-cheap-food-over

salvage

food stores / salvage grocery USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/15/

dining/salvage-stores-inflation.html

food poverty

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/

food-poverty

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/series/

hand-to-mouth-britains-food-insecurity-crisis

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/dec/27/

how-the-trussell-trust-grew-from-a-garden-shed-to-1300-food-banks

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2013/jul/12/

michael-gove-school-meals-poverty

scavenge for meals

in garbage bins USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/03/us/

for-gay-community-finding-acceptance-is-even-more-difficult-on-the-streets.html

food aid

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/01/15/

953963243/why-billions-in-food-aid-hasnt-gotten-to-needy-families

Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program SNAP USA

SNAP,

formerly known as food

stamps

https://www.npr.org/2023/03/17/

1163131918/snap-benefits-food-hunger-pandemic-assistance

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/31/

upshot/how-food-banks-succeeded-and-what-they-need-now.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2020/03/14/

815748914/judge-blocks-rule-that-would-have-kicked-700-000-people-off-snap

https://www.npr.org/2019/12/04/

784732180/nearly-700-000-snap-recipients-could-lose-benefits-under-new-trump-rule

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/06/04/

729733146/how-a-fight-over-beef-jerky-reveals-tensions-over-snap-in-the-trump-era

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/06/20/

621391895/in-some-states-drug-felons-still-face-lifetime-ban-on-snap-benefits

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/04/27/

606110654/unauthorized-immigrants-shy-away-from-signing-kids-up-for-food-aid

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/02/12/

585130274/trump-administration-wants-to-decide-what-food-snap-recipients-will-get

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/03/28/

521823480/deportation-fears-prompt-immigrants-to-cancel-food-stamps

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/03/03/

468955099/the-snap-gap-benefits-arent-enough-to-keep-many-recipients-fed

SNAP recipients

USA

https://www.npr.org/2019/12/04/

784732180/nearly-700-000-snap-recipients-could-lose-benefits-

under-new-trump-rule

food stamps

USA

food stamps (...)

help poor people

pay for their groceries

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/13/opinion/collins-the-house-just-wants-to-snack.html

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/food-stamps

https://www.npr.org/2019/06/26/

736181304/using-food-stamps-for-online-grocery-shopping-is-getting-easier

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/05/01/

606422692/why-millions-of-californians-eligible-for-food-stamps-dont-get-them

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/26/

opinion/trump-budget-food-stamps-wages.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/05/24/

529831472/trump-wants-families-on-food-stamps-to-get-jobs-the-majority-already-work

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/03/28/

521823480/deportation-fears-prompt-immigrants-to-cancel-food-stamps

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/13/

well/eat/food-stamp-snap-soda.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/01/31/

465059192/for-more-than-a-million-food-stamp-recipients-the-clock-is-now-ticking

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/12/29/

461409966/in-defense-of-food-stamps-why-the-white-house-sings-snaps-praises

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/09/18/

441143723/people-on-food-stamps-eat-less-nutritious-food-than-everyone-else

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/

us/politics/states-tighten-conditions-for-receiving-food-stamps-

as-the-economy-improves.html

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2015/03/20/

394149979/a-push-to-move-food-stamp-recipients-into-jobs

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/16/

the-insanity-of-our-food-policy/

http://takingnote.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/01/

eviscerating-the-food-stamps-program/

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/11/us/

11foodstamps.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/06/

opinion/l06food.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/29/us/

29foodstamps.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/11/28/us/20091128-

foodstamps.html

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/usa-2008-

the-great-depression-803095.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/31/us/

31foodstamps.html

food stamp program

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/13/

opinion/collins-the-house-just-wants-to-snack.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/13/

opinion/missing-the-food-stamp-program.html

cartoons > Cagle > Food stamps

USA 2013

http://www.cagle.com/news/food-stamp-cuts/

people on food stamps

USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/09/18/

441143723/people-on-food-stamps-eat-less-nutritious-food-than-everyone-else

food voucher UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/mar/26/

payment-cards-emergency-assistance-food-stamps

paperless food stamps

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/20/us/

20market.html

Illustration: Ben

Jennings

Ben Jennings

on

Philip Hammond and the public sector pay cap – cartoon

G

Sunday 16 July

2017 18.46 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2017/jul/16/

ben-jennings-on-philip-hammond-and-the-public-sector-pay-cap-cartoon

food banks UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/

food-banks

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/dec/27/

rainbow-playsuit-pink-ramp-wheelchair-barbie-like-looking-in-a-mirror

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/aug/24/

benefits-poverty-cost-of-living

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/feb/26/

food-bank-volunteer-living-on-the-breadline-warrington

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2022/apr/12/

ben-jennings-on-the-uks-cost-of-living-crisis-

cartoon - Guardian cartoon

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/mar/04/

rise-in-food-banks-in-uk-schools-highlights-depth-of-covid-crisis-survey

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/dec/19/

this-is-supposed-to-be-a-rich-country-

volunteers-on-the-reality-of-food-bank-britain

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2017/jul/16/

ben-jennings-on-philip-hammond-and-the-public-sector-pay-cap-

cartoon - Guardian cartoon

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/may/01/

food-banks-most-people-at-the-school-gates-have-used-them

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cartoon/2014/apr/01/

george-osborne-full-employment-plan-steve-bell-

cartoon - Guardian cartoon

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/mar/20/

lord-tebbit-scorns-food-bank-demand

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/feb/20/

bishops-blame-cameron-food-bank-crisis

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/20/

food-bank-review-undermines-ministers-claim

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/sep/11/

food-bank-britain-didnt-ask-be-ill

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/aug/16/

food-bank-britain-jay-rayner

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/dec/23/

christmas-food-handouts-families-poverty

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/jan/17/

eating-heating-furniture-cold-weather

multibank

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/article/2024/jul/21/

gordon-brown-launches-londons-first-multibank-

amid-uk-child-poverty-fears

NPR podcasts

food banks, food pantries

USA

https://projects.propublica.org/trump-food-cuts/ - Oct. 3, 2025

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/

usa-trump-ohio/ - June 7, 2025

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/

trump-cuts-hit-struggling-food-banks-

risking-hunger-low-income-americans-2025-03-25/

https://www.npr.org/2022/06/02/

1101473558/demand-food-banks-inflation-supply-chain

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/31/

upshot/how-food-banks-succeeded-and-what-they-need-now.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/12/25/

949643418/fishermen-team-up-with-food-banks-to-help-hungry-families

https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/12/02/

940555647/immigrant-woman-starts-food-pantry-in-her-home-

to-help-undocumented-families

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/04/

opinion/coronavirus-food-banks-hunger.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/01/

nyregion/coronavirus-food-bank-lines-nyc.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/

neediest-cases/feeding-america-food-banks-coronavirus.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/

business/economy/coronavirus-food-banks.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/11/28/

783066219/food-pharmacies-in-clinics-

when-the-diagnosis-is-chronic-hunger

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/01/16/

577662116/food-stamp-program-makes-fresh-produce-more-affordable

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/09/18/

551796954/one-of-americas-biggest-food-banks-just-cut-junk-food-

by-84-percent-in-a-year

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/08/01/

540638754/beyond-pantries-this-food-bank-invests-in-the-local-community

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/05/22/

529493413/in-some-rural-counties-hunger-is-rising-but-food-donations-arent

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/21/

health/diabetes-food-banks.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/25/us/

at-detroit-food-bank-founders-are-gone-but-mission-endures.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/20/nyregion/

20food.html

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/11/11/

giving/20081111-FOOD_index.html

food pantry

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/12/02/

940555647/immigrant-woman-starts-food-pantry-in-her-home-

to-help-undocumented-families

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/08/01/

540638754/beyond-pantries-this-food-bank-invests-in-the-local-community

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/01/11/

508931473/a-new-type-of-food-pantry-is-sprouting-in-yards-across-america

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/us/

politics/states-tighten-conditions-for-receiving-food-stamps-

as-the-economy-improves.html

emergency food pantry

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/20/

business/economy/study-finds-

greater-income-inequality-in-nations-thriving-cities.html

food bank crisis

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/feb/20/

bishops-blame-cameron-food-bank-crisis

militant grocers

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/feb/26/

britains-new-wave-of-militant-grocers-food-waste

Christmas food handouts UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/dec/23/

christmas-food-handouts-families-poverty

food lines

drive-in soup kitchen

soup runs

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2003/dec/17/

homelessness.uknews

soup runner

Ellen Turner,

left, and her twin sister, Helen Ashe,

in aprons Oprah

Winfrey gave them

when they appeared on her show.

Photograph: The Love Kitchen

Ellen Turner Dies

at 87;

Opened Kitchen to Feed the Needy of Knoxville

NYT

APRIL 25, 2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/26/us/

ellen-turner-dies-at-87-opened-kitchen-to-feed-the-needy-of-knoxville.html

Migrant mother

Florence Thompson & children

photographed by Dorothea Lange.

Location: Nipomo, CA, US

Date taken: 1936

Photograph:

Dorothea Lange

Life Images

Corpus of news articles

Economy > Poverty > Food

Poverty

in America:

Why Can’t We End It?

July 28,

2012

The New York Times

By PETER EDELMAN

RONALD

REAGAN famously said, “We fought a war on poverty and poverty won.” With 46

million Americans — 15 percent of the population — now counted as poor, it’s

tempting to think he may have been right.

Look a little deeper and the temptation grows. The lowest percentage in poverty

since we started counting was 11.1 percent in 1973. The rate climbed as high as

15.2 percent in 1983. In 2000, after a spurt of prosperity, it went back down to

11.3 percent, and yet 15 million more people are poor today.

At the same time, we have done a lot that works. From Social Security to food

stamps to the earned-income tax credit and on and on, we have enacted programs

that now keep 40 million people out of poverty. Poverty would be nearly double

what it is now without these measures, according to the Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities. To say that “poverty won” is like saying the Clean Air and

Clean Water Acts failed because there is still pollution.

With all of that, why have we not achieved more? Four reasons: An astonishing

number of people work at low-wage jobs. Plus, many more households are headed

now by a single parent, making it difficult for them to earn a living income

from the jobs that are typically available. The near disappearance of cash

assistance for low-income mothers and children — i.e., welfare — in much of the

country plays a contributing role, too. And persistent issues of race and gender

mean higher poverty among minorities and families headed by single mothers.

The first thing needed if we’re to get people out of poverty is more jobs that

pay decent wages. There aren’t enough of these in our current economy. The need

for good jobs extends far beyond the current crisis; we’ll need a

full-employment policy and a bigger investment in 21st-century education and

skill development strategies if we’re to have any hope of breaking out of the

current economic malaise.

This isn’t a problem specific to the current moment. We’ve been drowning in a

flood of low-wage jobs for the last 40 years. Most of the income of people in

poverty comes from work. According to the most recent data available from the

Census Bureau, 104 million people — a third of the population — have annual

incomes below twice the poverty line, less than $38,000 for a family of three.

They struggle to make ends meet every month.

Half the jobs in the nation pay less than $34,000 a year, according to the

Economic Policy Institute. A quarter pay below the poverty line for a family of

four, less than $23,000 annually. Families that can send another adult to work

have done better, but single mothers (and fathers) don’t have that option.

Poverty among families with children headed by single mothers exceeds 40

percent.

Wages for those who work on jobs in the bottom half have been stuck since 1973,

increasing just 7 percent.

It’s not that the whole economy stagnated. There’s been growth, a lot of it, but

it has stuck at the top. The realization that 99 percent of us have been left in

the dust by the 1 percent at the top (some much further behind than others) came

far later than it should have — Rip Van Winkle and then some. It took the Great

Recession to get people’s attention, but the facts had been accumulating for a

long time. If we’ve awakened, we can act.

Low-wage jobs bedevil tens of millions of people. At the other end of the

low-income spectrum we have a different problem. The safety net for single

mothers and their children has developed a gaping hole over the past dozen

years. This is a major cause of the dramatic increase in extreme poverty during

those years. The census tells us that 20.5 million people earn incomes below

half the poverty line, less than about $9,500 for a family of three — up eight

million from 2000.

Why? A substantial reason is the near demise of welfare — now called Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF. In the mid-90s more than two-thirds of

children in poor families received welfare. But that number has dwindled over

the past decade and a half to roughly 27 percent.

One result: six million people have no income other than food stamps. Food

stamps provide an income at a third of the poverty line, close to $6,300 for a

family of three. It’s hard to understand how they survive.

At least we have food stamps. They have been a powerful antirecession tool in

the past five years, with the number of recipients rising to 46 million today

from 26.3 million in 2007. By contrast, welfare has done little to counter the

impact of the recession; although the number of people receiving cash assistance

rose from 3.9 million to 4.5 million since 2007, many states actually reduced

the size of their rolls and lowered benefits to those in greatest need.

Race and gender play an enormous part in determining poverty’s continuing

course. Minorities are disproportionately poor: around 27 percent of

African-Americans, Latinos and American Indians are poor, versus 10 percent of

whites. Wealth disparities are even wider. At the same time, whites constitute

the largest number among the poor. This is a fact that bears emphasis, since

measures to raise income and provide work supports will help more whites than

minorities. But we cannot ignore race and gender, both because they present

particular challenges and because so much of the politics of poverty is grounded

in those issues.

We know what we need to do — make the rich pay their fair share of running the

country, raise the minimum wage, provide health care and a decent safety net,

and the like. But realistically, the immediate challenge is keeping what we

have. Representative Paul Ryan and his ideological peers would slash everything

from Social Security to Medicare and on through the list, and would hand out

more tax breaks to the people at the top. Robin Hood would turn over in his

grave.

We should not kid ourselves. It isn’t certain that things will stay as good as

they are now. The wealth and income of the top 1 percent grows at the expense of

everyone else. Money breeds power and power breeds more money. It is a truly

vicious circle.

A surefire politics of change would necessarily involve getting people in the

middle — from the 30th to the 70th percentile — to see their own economic

self-interest. If they vote in their own self-interest, they’ll elect people who

are likely to be more aligned with people with lower incomes as well as with

them. As long as people in the middle identify more with people on the top than

with those on the bottom, we are doomed. The obscene amount of money flowing

into the electoral process makes things harder yet.

But history shows that people power wins sometimes. That’s what happened in the

Progressive Era a century ago and in the Great Depression as well. The gross

inequality of those times produced an amalgam of popular unrest, organization,

muckraking journalism and political leadership that attacked the big — and

worsening — structural problem of economic inequality. The civil rights movement

changed the course of history and spread into the women’s movement, the

environmental movement and, later, the gay rights movement. Could we have said

on the day before the dawn of each that it would happen, let alone succeed? Did

Rosa Parks know?

We have the ingredients. For one thing, the demographics of the electorate are

changing. The consequences of that are hardly automatic, but they create an

opportunity. The new generation of young people — unusually distrustful of

encrusted power in all institutions and, as a consequence, tending toward

libertarianism — is ripe for a new politics of honesty. Lower-income people will

participate if there are candidates who speak to their situations. The change

has to come from the bottom up and from synergistic leadership that draws it

out. When people decide they have had enough and there are candidates who stand

for what they want, they will vote accordingly.

I have seen days of promise and days of darkness, and I’ve seen them more than

once. All history is like that. The people have the power if they will use it,

but they have to see that it is in their interest to do so.

Peter Edelman

is a professor of law

at Georgetown University

and the

author, most recently,

of “So Rich,

So Poor:

Why It’s So Hard to End Poverty in America.”

Poverty in America: Why Can’t We End It?,

NYT,

28.7.2012,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/29/

opinion/sunday/why-cant-we-end-poverty-in-america.html

Poor

Are Still Getting Poorer,

but

Downturn’s Punch Varies,

Census Data Show

September

15, 2011

The New York Times

By JASON DePARLE

and SABRINA TAVERNISE

WASHINGTON — The discouraging numbers spilling from the Census Bureau’s poverty

report this week were a disquieting reminder that a weak economy continues to

spread broad and deep pain.

And so it does. But not evenly.

The Midwest is battered, but the Northeast escaped with a lighter knock. The

incomes of young adults have plunged — but those of older Americans have

actually risen. On the whole, immigrants have weathered the storm a bit better

than people born here. In rural areas, poverty remained unchanged last year,

while in suburbs it reached the highest level since 1967, when the Census Bureau

first tracked it.

Yet one old problem has not changed: the poor have rapidly gotten poorer.

The report, an annual gauge of prosperity and pain, is sure to be cited in

coming months as lawmakers make difficult decisions about how to balance the

competing goals of cutting deficits and preserving safety nets.

Its overall findings — income down, poverty up — are hardly surprising in the

worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Of equal interest, with

fiscal knives in the air, are the looks at who has suffered the most and who has

largely escaped.

“Certainly in a recession we want to put resources where they’re most needed,”

said Eugene Steuerle of the Urban Institute, who served as a Treasury official

under Democratic and Republican presidents. “And in a recession, needs change

dramatically from group to group.”

Perhaps no households have weathered the downturn better than those headed by

people 65 and older, whose incomes rose 5.5 percent from 2007 to 2010. By

contrast, household income for every other age group fell. Among people ages 15

to 24, it plunged 15.3 percent.

Partly that is because older Americans get more of their income from pensions

and investments, so a job shortage hurts them less. Also, the generation now

retiring has been the most prosperous in history, so as poorer Americans die

off, the income of the age group grows.

Such data is likely to feed longstanding debates about generational equity,

since the largest portion of safety net spending goes to those 65 and older,

through Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

“We are spending too much of our limited resources on the elderly, and not

investing enough in programs for younger Americans, such as job training and

education,” said Isabel V. Sawhill, a budget expert at the Brookings

Institution.

Another noteworthy finding comes from the suburbs, which have traditionally had

the lowest rates of poverty. Suburban dwellers experienced a sharp increase

toward the end of the past decade. Nearly 12 percent of them were living in

poverty in 2010, the highest level ever recorded, up from just 8 percent in

2001. (The rate in cities was 19 percent, but rose less sharply.)

“There’s been a suburbanization of poverty,” said Alan Berube, a Brookings

demographer, who cited the growth of service, retail and construction jobs that

lured low-income Americans to the suburbs before the recession. “The notion of

poverty being only in inner cities and isolated rural areas is increasingly out

of step with reality.”

Household income fell in every region of the country from 2007 to 2010. But it

fell much less in the Northeast (3.1 percent) than in the South (6.3 percent),

the West (6.7 percent) or the Midwest (8.4 percent). And the Northeast was the

only region where household income did not fall last year.

The declines in the West have been fueled in part by the collapse of the housing

industry, especially in Arizona and Nevada. And the Midwest has suffered idled

factories. Its status as the hardest-hit region is likely to come into play next

year as presidential candidates hunt such big Electoral College prizes as

Michigan, Iowa, Wisconsin and Ohio.

“The big hurt has been in the manufacturing and construction industries, which

were big in the Midwest and West,” said Timothy Smeeding, an economist at the

University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The census findings present two competing stories of immigrants — a reminder of

just how economically diverse that group has become. From 2007 to 2010, they

have fared both better and worse than the native born.

Among people born in the United States, household incomes declined 6.1 percent.

Among non-citizens, the decline was steeper — 8 percent. But for immigrants who

had attained citizenship, the decline was only 3.9 percent.

That latter group may disproportionately include the highly educated

professionals who increasingly fill the new Americans’ ranks. A recent study by

Audrey Singer, a demographer at the Brookings Institution, found that the number

of immigrants with college degrees now exceeds those who lack a high school

education.

“The high-skilled people are starting to dominate,” she said

Two worrisome numbers in the report raise questions about the recent response of

the safety net. Poverty has risen especially fast among single mothers. More

than 40 percent of households headed by women now live in poverty, which is

defined as $17,568 for a family of three.

That is the first time since 1997 that figure has been so high. Analysts

attribute the rise in part to changes in the welfare system, enacted in the

mid-1990s, which make cash aid much harder to get. Those changes were credited

with encouraging recipients to work in good times, but may leave them with less

protection when jobs disappear.

“The business cycle is going to hurt them a lot more than it used to,” said

Robert Moffitt, a Johns Hopkins University economist.

Poor people not only grew more numerous — 46.2 million — but also poorer. Among

the poor, the share in deep poverty (defined as having less than half the income

to escape poverty) rose to the highest level in 36 years: 44.3 percent.

The census data may overstate hardship by failing to count some benefits the

needy receive, like tax credits and food stamps. But it also may also understate

their needs by failing to adjust for health care expenses and variations in the

cost of living.

About 20.5 million people are in deep poverty, with food stamps increasingly

replacing cash aid as the safety net of last resort. More than 45 million people

get food stamps, an increase of 64 percent since January 2008. About one in

eight Americans, and one in four children, receives aid. Using an alternative

definition of income, the Census Bureau found that food stamps lifted 3.9

million people above the poverty line.

“Given that poverty and hardship are likely to continue for some time, it’s

imperative that we protect the program,” said Stacy Dean, an analyst at the

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which aids in food stamp outreach

campaigns.

Poor Are Still Getting Poorer, but Downturn’s Punch

Varies,

Census Data Show,

NYT,

15.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/15/us/

poor-are-still-getting-poorer-but-downturns-punch-varies-census-data-show.html

At East Village Food Pantry,

the Price Is a Sermon

September 28, 2010

The New York Times

By JOSEPH BERGER

The shopping carts are lined up hours early in Tompkins Square Park, not far

from the dog run, where the East Village’s more genteel residents are unleashing

retrievers and beagles and chatting animatedly. The poor or elderly waiting on

benches to get the free food that comes with a dose of the Gospel seem more lost

in their own thoughts, even though many meet every Tuesday.

A guard, Mike Luke, a powerhouse known as Big Mike who himself was a consumer at

church pantries until he found religion and decided to work for “the man

upstairs,” manages the crowd with crisp authority until the 11 a.m. service

starts across the street at the Tompkins Square Gospel Fellowship. There is

nervous tension because only the first 50 will get in, and suddenly two women

are squabbling over a black cart.

“How do you know that’s your cart?” Big Mike firmly asks one, a fair question

since the carts look alike. But the mystery is cleared up with the discovery of

an orphaned gray cart.

Inside the worship hall, the 50 men and women sit in neat rows in front of a

pulpit and a painting of a generic waterfall while a pianist softly plays hymns.

Their carts are reassembled in neat rows as well.

The room has the shopworn air of Sergeant Sarah Brown’s Save-a-Soul Mission in

“Guys and Dolls.” One almost expects Stubby Kaye to get up and sing “Sit Down,

You’re Rockin’ the Boat.” But people don’t mind having to sit through a sermon

as the price of admission, and few have jobs they need to run to. While they

wait, volunteers fill each cart with a couple of bread loaves — redolent of a

Gospel miracle, except these are ciabatta and 10-grain — a couple of bananas, a

couple of less-than-freshly-picked ears of corn, a box of eggs, a box of

blueberries, even an Asian pear.

The food is donated by Trader Joe’s, the gourmet and organic food purveyor,

which has a store nearby. It usually feeds the kinds of professionals who use

the dog run, but it provides the fellowship with a wealth of unsold baked goods,

fruit and vegetables.

The fellowship was started 115 years ago as a mission to the immigrant Jews of

the Lower East Side but now mostly serves the black, Latino and Asian poor. The

East Village has several other pantries that dispense food without sermons;

their food is government-financed and so must be religion-free. The fellowship

started its giveaways in January and now feeds 250 people during three services

on Tuesdays — one in Chinese — and a single evening service on Sundays and

Wednesdays.

The mission is run by the Rev. Bill Jones, a lively ordained Baptist minister

from the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.

“People are not only hungry for food, but hungry for the word of God,” Mr. Jones

said. “There’s not just a physical need but a spiritual need.”

Nevertheless, he is aware of the actual hunger. “If you wait for three hours to

get $25 worth of groceries,” he said, “you have a need.”

He affirms that thought to the waiting crowd in a stentorian drawl.

“You all get blueberries today,” he announces. “Some of you get eggs. If you

don’t get eggs, don’t be upset. You neighbor is getting eggs, so be grateful.”

The people who come include Rafael Mercado, 52, who lost his job as a mailroom

clerk four years ago.

“I don’t have the kind of money now to go shopping,” he said, “so I go to many

pantries.” Another is Asia Feliciano, 37, a single mother with a lush head of

cornrow braids. She and her sons, Trevor, 5, and Jordan, 3, live in a nearby

shelter, and they stumbled upon the mission in August while panhandling.

“It puts food on our plates every night,” she said.

Mr. Jones begins the service with a prayer — “Heavenly father, we are so

grateful for the provisions you have brought us for another day.” He then offers

a lesson from the Gospel of John, in which Jesus tells the disciples to love one

another. With ardor that is not quite brimstone, Mr. Jones urges listeners to

love one another as well, not give in to temptations and pray to remain faithful

to God.

Many among the 50 sit stone-faced. But some clearly listen. Though she comes

mostly for the food, Ms. Feliciano indicates that the worship has subversively

taken hold.

“When I have to sit through the service, it opens my eyes,” she said. “So I

started reading the Bible and I asked them for a Bible, and they gave me one.”

Jim Dwyer is on leave.

At East Village Food

Pantry,

the Price Is a Sermon,

NYT,

28.9.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/29/nyregion/29about.html

Recession Raises Poverty Rate

to a 15-Year High

September 16, 2010

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

The percentage of Americans struggling below the poverty line in 2009 was the

highest it has been in 15 years, the Census Bureau reported Thursday, and

interviews with poverty experts and aid groups said the increase appeared to be

continuing this year.

With the country in its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, four

million additional Americans found themselves in poverty in 2009, with the total

reaching 44 million, or one in seven residents. Millions more were surviving

only because of expanded unemployment insurance and other assistance.

And the numbers could have climbed higher: One way embattled Americans have

gotten by is sharing homes with siblings, parents or even nonrelatives,

sometimes resulting in overused couches and frayed nerves but holding down the

rise in the national poverty rate, according to the report.

The share of residents in poverty climbed to 14.3 percent in 2009, the highest

level recorded since 1994. The rise was steepest for children, with one in five

affected, the bureau said.

The report provides the most detailed picture yet of the impact of the recession

and unemployment on incomes, especially at the bottom of the scale. It also

indicated that the temporary increases in aid provided in last year’s stimulus

bill eased the burdens on millions of families.

For a single adult in 2009, the poverty line was $10,830 in pretax cash income;

for a family of four, $22,050.

Given the depth of the recession, some economists had expected an even larger

jump in the poor.

“A lot of people would have been worse off if they didn’t have someone to move

in with,” said Timothy M. Smeeding, director of the Institute for Research on

Poverty at the University of Wisconsin.

Dr. Smeeding said that in a typical case, a struggling family, like a mother and

children who would be in poverty on their own, stays with more prosperous

parents or other relatives.

The Census study found an 11.6 percent increase in the number of such

multifamily households over the last two years. Included in that number was

James Davis, 22, of Chicago, who lost his job as a package handler for Fed Ex in

February 2009. As he ran out of money, he and his 2-year-old daughter moved in

with his mother about a year ago, avoiding destitution while he searched for

work.

“I couldn’t afford rent,” he said.

Danise Sanders, 31, and her three children have been sleeping in the living room

of her mother and sister’s one-bedroom apartment in San Pablo, Calif., for the

last month, with no end in sight. They doubled up after the bank foreclosed on

her landlord, forcing her to move.

“It’s getting harder,” said Ms. Sanders, who makes a low income as a mail clerk.

“We’re all pitching in for rent and bills.”

There are strong signs that the high poverty numbers have continued into 2010

and are probably still rising, some experts said, as the recovery sputters and

unemployment remains near 10 percent.

“Historically, it takes time for poverty to recover after unemployment starts to

go down,” said LaDonna Pavetti, a welfare expert at the Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities, a liberal-leaning research group in Washington.

Dr. Smeeding said it seemed almost certain that poverty would further rise this

year. He noted that the increase in unemployment and poverty had been

concentrated among young adults without college educations and their children,

and that these people remained at the end of the line in their search for work.

One indirect sign of continuing hardship is the rise in food stamp recipients,

who now include nearly one in seven adults and an even greater share of the

nation’s children. While other factors as well as declining incomes have driven

the rise, by mid-2010 the number of recipients had reached 41.3 million,

compared with 39 million at the beginning of the year.

Food banks, too, report swelling demand.

“We’re seeing more younger people coming in that not only don’t have any food,

but nowhere to stay,” said Marla Goodwin, director of Jeremiah’s Food Pantry in

East St. Louis, Ill. The pantry was open one day a month when it opened in 2008

but expanded this year to five days a month.

And Texas food banks said they distributed 14 percent more food in the second

quarter of 2010 than in the same period last year.

The Census report showed increases in poverty for whites, blacks and Hispanic

Americans, with historic disparities continuing. The poverty rate for

non-Hispanic whites was 9.4 percent, for blacks 25.8 percent and for Hispanics

25.3 percent. The rate for Asians was unchanged at 12.5 percent.

The median income of all households stayed roughly the same from 2008 to 2009.

It had fallen sharply the year before, as the recession gained steam and remains

well below the levels of the late 1990s — a sign of the stagnating prospects for

the middle class.

The decline in incomes in 2008 had been greater than expected, and when the two

recession years are considered together, the decline since 2007 was 4.2 percent,

said Lawrence Katz, an economist at Harvard. Gains achieved earlier in the

decade were wiped out, and median family incomes in 2009 were 5 percent lower

than in 1999.

“This is the first time in memory that an entire decade has produced essentially

no economic growth for the typical American household,” Mr. Katz said.

The number of United States residents without health insurance climbed to 51

million in 2009, from 46 million in 2008, the Census said. Their ranks are

expected to shrink in coming years as the health care overhaul adopted by

Congress in March begins to take effect.

Government benefits like food stamps and tax credits, which can provide hundreds

or even thousands of dollars in extra income, are not included in calculating

whether a family’s income falls above or below the poverty line.

But rises in the cost of housing, medical care or energy and the large regional

differences in the cost of living are not taken into account either.

If food-stamp benefits and low-income tax credits were included as income, close

to 8 million of those labeled as poor in the report would instead be just above

the poverty line, the Census report estimated. At the same time, a person who

starts a job and receives the earned income tax credit could have new

work-related expenses like transportation and child care. Unemployment benefits,

which are considered cash income and included in the calculations, helped keep 3

million families above the line last year, the report said, with temporary

extensions and higher payments helping all the more.

The poverty line is a flawed measure, experts agree, but it remains the best

consistent long-term gauge of need available, and its ups and downs reflect

genuine trends.

The federal government will issue an alternate calculation next year that will

include important noncash and after-tax income and also account for regional

differences in the cost of living.

But it will continue to calculate the rate in the old way as well, in part

because eligibility for many programs, from Medicaid to free school lunches, is

linked to the longstanding poverty line.

Reporting was contributed by Rebecca Cathcart in Los Angeles,

Emma Graves

Fitzsimmons in Chicago, Malcolm Gay in St. Louis,

Robert Gebeloff in New York

and Malia Wollan in San Francisco.

Recession Raises Poverty

Rate to a 15-Year High, NYT, 16.9.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/17/us/17poverty.html

Poor in UK

dying 10 years earlier than rich,

despite years of

government action

Department of Health and NHS criticised

for making too little progress

on

tackling key barometer of inequality

Denis Campbell, health correspondent

The Guardian, Friday 2 July 2010

This article appeared on p1 of the Main section section

of the Guardian

on

Friday 2 July 2010.

It was published on guardian.co.uk

at 00.05 BST

on Friday 2 July 2010.

It was last modified at 00.05 BST on Friday 2 July 2010.

The life expectancy gap between rich and poor people in England is widening,

despite years of government and NHS action, a hard-hitting National Audit Office

report reveals today.

Extensive efforts have failed to reduce the wide differential, which can still

be 10 years or more depending on socio-economic background, says the public

spending watchdog. While life expectancy has risen generally, it is increasing

at a slower rate for England's poorest citizens.

In Blackpool, for example, men live for an average of 73.6 years, which is 10.7

fewer than men in Kensington and Chelsea in central London, who reach 84.3

years. Similarly, women in the Lancashire town typically die at 78.8 years –

10.1 years earlier than those in the London borough, who reach an average 89.9.

The gap in life expectancy between government-designated areas of high

deprivation and the national average has continued to widen, so Labour's aim of

reducing it by 10% will not be met, the NAO concludes. The failure to meet the

target has cost an estimated 3,300 lives.

The report criticises the Department of Health and the NHS for making too little

progress to tackle this key barometer of inequality. Although the DoH set a

target in 2000 to reduce health inequalities and published a strategy in 2003,

real NHS action did not begin until 2006, it says.

"The Department of Health has made a concerted effort to tackle a very difficult

and long-standing problem," said Amyas Morse, head of the NAO.

"However, it was slow to take action and health inequalities were not a top

priority for the NHS until 2006."

The service was also slow to apply three key policies, including giving more

poor people drugs to reduce their blood pressure or cholesterol level. "These

have yet to be adopted on the scale required to close the inequalities gap," the

NAO said.

The report also highlights a continuing lack of GPs in poor areas with high

health need, despite shortages having been identified as a problem in 2000. It

is also unclear whether an extra £230 a head spent in some areas to improve

health outcomes has had any real impact.

Professor Alan Maryon-Davis, president of the UK Faculty of Public Health, said

the disparities showed the inequality of English society. "If we see ourselves

as a civilised society, these gaps are an indication of unfairness, which

shouldn't be there, and is an unfairness which costs lives, damages people's

health and will eventually be a huge burden on the NHS if they aren't tackled,"

he said.

But the NAO report did contain good news about improvements in the health of

England's poorest citizens, he added. "The health of the people in the poorest

areas is going in the right direction – that's good news. We shouldn't regard

that as a failure. But the bulk of the population are improving their health at

a faster rate." He urged ministers to resist any temptation to cut spending on

health inequalities in the tough financial climate.

Anne Milton, the public health minister, emphasised the government's belief in

health equality. "Everyone should have the same opportunities to lead a healthy

life no matter where they live. We want the public's health to be at the very

heart of all we do, not just in the NHS but across government," she said.

"This report shows that efforts have been made to address health inequalities

but that more needs to be done to tackle the deep-rooted social problems that

cause ill-health. I want to see the NHS, doctors and local government acting at

the right time to improve the health of those who need it most."

The NHS Confederation, which represents most health service organisations,

admitted that more progress was needed. Jo Webber, its deputy policy director,

said: "The NHS and its partners, especially in local government, have a

responsibility to help stop people falling into and continuing in ill-health

rather than picking up the pieces when it may be too late. Encouraging improved

health requires a focus on all aspects of society, including economic

inequality, and quality of life in early years."

Tammy Boyce, of the King's Fund health thinktank, said the NHS could only

achieve so much. "Tackling health inequalities is not a task for the NHS alone.

It requires a co-ordinated, long-term commitment across government to address

the wider causes of ill health such as poverty and poor housing," she said.

"The first test of whether the coalition government is likely to succeed where

the previous government failed will come in this autumn's spending review. It is

vital that cross-cutting issues like health inequalities are not overlooked in

the scramble to deliver spending cuts on a department-by-department basis."

Michelle Mitchell, charity director at Age UK, said the big gap in life

expectancy had to be tackled in the light of the government's intention to

increase the age at which people can draw the state pension. "With a 13-year

disparity in life expectancy between different areas of the country, it's

shocking that primary care trusts are still failing to use simple and effective

treatments to help tackle the problem.

"This report follows the government's announcement last week to raise the state

pension age further and faster, which will hit those with a shorter life

expectancy in the poorest areas of Britain hardest," she said. "In this context,

tackling health inequalities is more urgent than ever and the government must

set ambitious targets to close the yawning life expectancy divide."

Poor in UK dying 10 years earlier than rich,

despite years of government action, G, 2.7.2010,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/jul/02/

poor-in-uk-dying-10-years-earlier-than-rich

Forced to choose eating or heating,

family burns furniture to

keep warm

Demand for free parcels at food banks soars

as big freeze leaves

many unable

to pay for both food and warmth

Sunday 17 January 2010

19.06 GMT

Guardian.co.uk

Paul Lewis

This article was published on guardian.co.uk

at 19.06 GMT

on Sunday 17 January

2010.

A version appeared on p6 of the UK news section

of the Guardian

on Monday 18

January 2010.

It was last modified at 19.07 GMT

on Sunday 17 January 2010.

Holly Billen sat perched on the edge of her sofa, holding the

bump of her unborn child and nervously biting her lip. "It's nothing to be proud

of to say you don't have the money to feed yourself," she said. "But I'm not

ashamed to say it."

Aged 26 and eight months pregnant, she has had to endure most prolonged cold

snap in her lifetime. The soaring heating costs mean the choice between going

cold or going hungry has become a daily dilemma.

Food is sacrificed for warmth in her terraced cottage in Wilton, Wiltshire, not

least because her eight-year-old son, Brandon, has contracted a succession of

colds. "I've felt really bad some nights," she said. "He's in bed, and really

cold. But there's no money for the extra heat. So its extra blankets and socks

and vests under pyjamas."

Recently, she turned to a less conventional remedy for the sub-zero

temperatures. Completely out of money for gas, she took apart a shelf unit to

use as fuel in her fireplace. "I figured I needed it more for heat than

storage," she said. "My boyfriend came into the garden because he heard me out

there with a saw."

It may sound like a story set in the Victorian era, but Billen, a dancer, is not

alone. She is among thousands of people who have begun relying on food handouts

to free up money to spend on heating during what the Met Office is describing as

the longest spell of freezing conditions since December 1981. While some areas

had milder weather today, forecasters said fresh snow could arrive by Tuesday.

Empty shelves

Four miles from Billen's home, the depot for the largest food bank in the

country is feeling the strain. In the cold weather, demand has doubled at the

depot, on the outskirts of Salisbury, and the shelves that normally hold fruit

juice, sugar and canned meat are nearly empty.

The Trussell Trust, a Christian charity that runs the depot and a network of 56

others across the country, said the cold has led to an unprecedented demand for

its parcels, which contain enough donated items to keep a family fed for six

days. To qualify for a box of food under the scheme, an individual or family

needs to be provided with a voucher by a care professional such as a teacher,

social worker or doctor. In December – when the freezing weather in large parts

of the UK began to bite – demand more than tripled in some places. Some of the

busiest banks have been in Scotland, site of some of the worst weather and

lowest temperatures. A food bank in Ebbw Vale, south Wales, provided food to 118

families in December – up from 74 the previous month. During the same period,

demand for tinned food and drink from the Suffolk bank jumped from 29 to 197

families.

The charity says initial feedback suggests there has been similar, if not

higher, demand for handouts in January, an increase it puts down to the rising

costs of heating homes.

There have been a raft of measures introduced in recent years to help people

cope with financial cost of cold weather, and over 12.3molder people will

benefit from winter fuel payments this year, totalling about £2.7bn. Already the

Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) has paid out an additional £260m this

winter to families under the cold weather payment scheme, which grants £25 a

week to some vulnerable households when – as has happened across the UK – the

temperature falls to zero for seven consecutive days.

"As temperatures plummet, I don't want vulnerable people to feel left in the

cold," DWP minister Helen Goodman said recently. "The payments are automatic so

everyone entitled will get them and should not worry about turning up their

heating." But not every vulnerable family is entitled, and even those who

receive the payments complain they do not absorb the spike in bills.

Research by Age Concern has shown that, despite government relief, one in five

older people skip meals to save money for heating. Tonight the charity urged

ministers to do more to ease pressure forcing elderly people into the "cruel

choice" between food or warmth.

On Wednesday last week, Northamptonshire county council announced a serious case

review into the deaths of Jean and Derek Randall, a couple believed to be in

their 70s whose bodies were found in their frozen home. Their cause of death is

unclear but neighbours told a local radio station the couple were relying on a

single electric heater and the electric hob rings on their cooker for warmth.

"It's completely inappropriate in 21st-century Britain that pensioners should

experience such an ordeal and die such tragic deaths," said the couple's Labour

MP, Sally Keeble.

Chris Mould, director of the Trussell Trust, said people in poverty were more

likely to use expensive electric heaters and pre-payment gas meters. Aside from

higher bills, the Arctic climate has brought with it other expected costs, he

said. "We're seeing a lot of people who are in a crisis triggered by the cold

weather. Broken boilers. Broken cars. Things temporarily break down and cost

money, and these incidents can tip people into crisis. It's sort of sadly

obvious."

The government's cold winter subsidies do not apply to Billen who, instead of

receiving income support, gets £140 in working tax credits plus child benefit.

Still, she said her frustration is directed at her energy supplier, Southern

Electric.

When she struggled to pay a £500 bill last year, the company encouraged her to

sign up to a pre-payment meter that, she was told, would take a slice each time

she paid her bill in order to recoup the money she owed. A failure when the

machine was installed meant the debt was never paid, however, and Billen now

finds that, when she puts £10 in, Southern Electric automatically takes £7 to

pay the debt. That leaves £3, which pays for a few hours' heat. "I spent hours

on the phone to the call centre," she said. "I said to them, I'm expecting a

baby. I'm not working. I can't afford this. They basically said: 'Too bad'."

She was given a food bank voucher after explaining her predicament to her

midwife. "I loved the fact I could eat a meal without feeling guilty about not

spending the money on heating," she said.

Pre-payment meters

A spokesperson for Scottish and Southern Energy, which owns Southern Electric,

encouraged anyone in Billen's position to contact them, and said it would

provide an "individual, tailor-made package" to help people keep warm.

Hours after the Guardian told the company it would feature Billen's story, she

received a call from the company. "They're coming as soon as they can to take

the meter out," she said. "They're lowering the repayment of existing debt to a

third of what it was. And I'm going to pay monthly. Really I'll end up paying a

hell of a lot less."

But not every family struggling to pay their energy bills can benefit from what

Billen thought was a brazen, though welcome, public relations stunt. Many feel

ignored; they say the nightly television news bulletins about travel chaos,

problems with gritters and school closures belie the more severe plight that

cold weather has brought to people in poverty.

Mark Ward, who manages the Salisbury food bank, said he had seen "much younger"

clients using it recently. . He recently delivered food to a young couple with a

baby in the nearby village of Dinton. All three were eating, sleeping and living

the single dowstairs room they could afford to heat.

Another beneficiary of the food bank, Donna Buxton, 38, a

partially blind mother from Great Bedwyn, had a similar story. "I've been

putting £30 a week in my meter and the heating wasn't keeping the place warm, so

I brought the mattress into the living room," she said. "Me and my 11-year-old

daughter, Libby, slept in there with two quilts and the cat."

A short walk from the Salisbury depot in Bermerton Heath, one of the poorest

areas in the market town, there are similar stories behind most front doors.

Lucy and Mark Mitchell, food bank recipients in their 20s, said they had taken

to sleeping in the same bed as their two young boys to keep warm.

Inside a cold flat on the edge of the estate, Mick Cutler, 56, an out-of-work

van driver, explained how his wife, Julie, and 10-year-old stepson were making

do with hot water bottles rather than radiators. They too have turned to the

bank for food.

"Really you're begging, aren't you?" he said. "But it's bloody hard to be honest

with you. I'm not too bad – I don't feel the cold as much as Julie and Matthew,"

he said. "He does go to bed with his clothes on sometimes. When he has a bath,

he wants to have the heating on, but I have to say 'no'. I feel guilty. How can

you tell a 10-year-old you can't keep him warm?"

Forced to choose eating

or heating,

family burns furniture to keep warm, G, 17.1.2010,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/jan/17/

eating-heating-furniture-cold-weather

The Safety Net

Living on Nothing but Food Stamps

January 3, 2010

The New York Times

By JASON DEPARLE

and ROBERT M. GEBELOFF

CAPE CORAL, Fla. — After an improbable rise from the Bronx projects to a job

selling Gulf Coast homes, Isabel Bermudez lost it all to an epic housing bust —

the six-figure income, the house with the pool and the investment property.

Now, as she papers the county with résumés and girds herself for rejection, she

is supporting two daughters on an income that inspires a double take: zero

dollars in monthly cash and a few hundred dollars in food stamps.

With food-stamp use at a record high and surging by the day, Ms. Bermudez

belongs to an overlooked subgroup that is growing especially fast: recipients

with no cash income.

About six million Americans receiving food stamps report they have no other

income, according to an analysis of state data collected by The New York Times.

In declarations that states verify and the federal government audits, they

described themselves as unemployed and receiving no cash aid — no welfare, no

unemployment insurance, and no pensions, child support or disability pay.

Their numbers were rising before the recession as tougher welfare laws made it

harder for poor people to get cash aid, but they have soared by about 50 percent

over the past two years. About one in 50 Americans now lives in a household with

a reported income that consists of nothing but a food-stamp card.

“It’s the one thing I can count on every month — I know the children are going

to have food,” Ms. Bermudez, 42, said with the forced good cheer she mastered

selling rows of new stucco homes.

Members of this straitened group range from displaced strivers like Ms. Bermudez

to weathered men who sleep in shelters and barter cigarettes. Some draw on

savings or sporadic under-the-table jobs. Some move in with relatives. Some get

noncash help, like subsidized apartments. While some go without cash incomes

only briefly before securing jobs or aid, others rely on food stamps alone for

many months.

The surge in this precarious way of life has been so swift that few policy

makers have noticed. But it attests to the growing role of food stamps within

the safety net. One in eight Americans now receives food stamps, including one

in four children.

Here in Florida, the number of people with no income beyond food stamps has

doubled in two years and has more than tripled along once-thriving parts of the

southwest coast. The building frenzy that lured Ms. Bermudez to Fort Myers and

neighboring Cape Coral has left a wasteland of foreclosed homes and written new

tales of descent into star-crossed indigence.

A skinny fellow in saggy clothes who spent his childhood in foster care, Rex

Britton, 22, hopped a bus from Syracuse two years ago for a job painting parking

lots. Now, with unemployment at nearly 14 percent and paving work scarce, he

receives $200 a month in food stamps and stays with a girlfriend who survives on

a rent subsidy and a government check to help her care for her disabled toddler.

“Without food stamps we’d probably be starving,” Mr. Britton said.

A strapping man who once made a living throwing fastballs, William Trapani, 53,

left his dreams on the minor league mound and his front teeth in prison, where

he spent nine years for selling cocaine. Now he sleeps at a rescue mission,

repairs bicycles for small change, and counts $200 in food stamps as his only

secure support.

“I’ve been out looking for work every day — there’s absolutely nothing,” he

said.

A grandmother whose voice mail message urges callers to “have a blessed good

day,” Wanda Debnam, 53, once drove 18-wheelers and dreamed of selling real

estate. But she lost her job at Starbucks this year and moved in with her son in

nearby Lehigh Acres. Now she sleeps with her 8-year-old granddaughter under a

poster of the Jonas Brothers and uses her food stamps to avoid her

daughter-in-law’s cooking.

“I’m climbing the walls,” Ms. Debnam said.

Florida officials have done a better job than most in monitoring the rise of

people with no cash income. They say the access to food stamps shows the safety

net is working.

“The program is doing what it was designed to do: help very needy people get

through a very difficult time,” said Don Winstead, deputy secretary for the

Department of Children and Families. “But for this program they would be in even

more dire straits.”

But others say the lack of cash support shows the safety net is torn. The main

cash welfare program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, has scarcely

expanded during the recession; the rolls are still down about 75 percent from

their 1990s peak. A different program, unemployment insurance, has rapidly

grown, but still omits nearly half the unemployed. Food stamps, easier to get,

have become the safety net of last resort.

“The food-stamp program is being asked to do too much,” said James Weill,

president of the Food Research and Action Center, a Washington advocacy group.

“People need income support.”

Food stamps, officially the called Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,

have taken on a greater role in the safety net for several reasons. Since the

benefit buys only food, it draws less suspicion of abuse than cash aid and more

political support. And the federal government pays for the whole benefit, giving

states reason to maximize enrollment. States typically share in other programs’

costs.

The Times collected income data on food-stamp recipients in 31 states, which

account for about 60 percent of the national caseload. On average, 18 percent

listed cash income of zero in their most recent monthly filings. Projected over

the entire caseload, that suggests six million people in households with no

income. About 1.2 million are children.

The numbers have nearly tripled in Nevada over the past two years, doubled in

Florida and New York, and grown nearly 90 percent in Minnesota and Utah. In

Wayne County, Mich., which includes Detroit, one of every 25 residents reports

an income of only food stamps. In Yakima County, Wash., the figure is about one

of every 17.

Experts caution that these numbers are estimates. Recipients typically report a

small rise in earnings just once every six months, so some people listed as

jobless may have recently found some work. New York officials say their numbers

include some households with earnings from illegal immigrants, who cannot get

food stamps but sometimes live with relatives who do.

Still, there is little doubt that millions of people are relying on incomes of

food stamps alone, and their numbers are rapidly growing. “This is a reflection

of the hardship that a lot of people in our state are facing; I think that is

without question,” said Mr. Winstead, the Florida official.

With their condition mostly overlooked, there is little data on how long these

households go without cash incomes or what other resources they have. But they

appear an eclectic lot. Florida data shows the population about evenly split

between families with children and households with just adults, with the latter

group growing fastest during the recession. They are racially mixed as well —

about 42 percent white, 32 percent black, and 22 percent Latino — with the

growth fastest among whites during the recession.

The expansion of the food-stamp program, which will spend more than $60 billion

this year, has so far enjoyed bipartisan support. But it does have conservative

critics who worry about the costs and the rise in dependency.

“This is craziness,” said Representative John Linder, a Georgia Republican who

is the ranking minority member of a House panel on welfare policy. “We’re at

risk of creating an entire class of people, a subset of people, just comfortable

getting by living off the government.”

Mr. Linder added: “You don’t improve the economy by paying people to sit around

and not work. You improve the economy by lowering taxes” so small businesses

will create more jobs.

With nearly 15,000 people in Lee County, Fla., reporting no income but food

stamps, the Fort Myers area is a laboratory of inventive survival. When Rhonda

Navarro, a cancer patient with a young son, lost running water, she ran a hose

from an outdoor spigot that was still working into the shower stall. Mr.

Britton, the jobless parking lot painter, sold his blood.

Kevin Zirulo and Diane Marshall, brother and sister, have more unlikely stories

than a reality television show. With a third sibling paying their rent, they are

living on a food-stamp benefit of $300 a month. A gun collector covered in

patriotic tattoos, Mr. Zirulo, 31, has sold off two semiautomatic rifles and a

revolver. Ms. Marshall, who has a 7-year-old daughter, scavenges discarded

furniture to sell on the Internet.

They said they dropped out of community college and diverted student aid to

household expenses. They received $150 from the Nielsen Company, which monitors

their television. They grew so desperate this month, they put the breeding

services of the family Chihuahua up for bid on Craigslist.

“We look at each other all the time and say we don’t know how we get through,”

Ms. Marshall said.

Ms. Bermudez, by contrast, tells what until the recession seemed a storybook

tale. Raised in the Bronx by a drug-addicted mother, she landed a clerical job

at a Manhattan real estate firm and heard that Fort Myers was booming. On a

quick scouting trip in 2002, she got a mortgage on easy terms for a $120,000

home with three bedrooms and a two-car garage. The developer called the floor

plan Camelot.

“I screamed, I cried,” she said. “I took so much pride in that house.”

Jobs were as plentiful as credit. Working for two large builders, she quickly

moved from clerical jobs to sales and bought an investment home. Her income

soared to $180,000, and she kept the pay stubs to prove it. By the time the glut

set in and she lost her job, the teaser rates on her mortgages had expired and

her monthly payments soared.

She landed a few short-lived jobs as the industry imploded, exhausted her

unemployment insurance and spent all her savings. But without steady work in

nearly three years, she could not stay afloat. In January, the bank foreclosed

on Camelot.

One morning as the eviction deadline approached, Ms. Bermudez woke up without

enough food to get through the day. She got emergency supplies at a food pantry

for her daughters, Tiffany, now 17, and Ashley, 4, and signed up for food

stamps. “My mother lived off the government,” she said. “It wasn’t something as

a proud working woman I wanted to do.”

For most of the year, she did have a $600 government check to help her care for

Ashley, who has a developmental disability. But she lost it after she was

hospitalized and missed an appointment to verify the child’s continued

eligibility. While she is trying to get it restored, her sole income now is $320

in food stamps.

Ms. Bermudez recently answered the door in her best business clothes and handed

a reporter her résumé, which she distributes by the ream. It notes she was once

a “million-dollar producer” and “deals well with the unexpected.”

“I went from making $180,000 to relying on food stamps,” she said. “Without that

government program, I wouldn’t be able to feed my children.”

Matthew Ericson contributed research.

Living on Nothing but

Food Stamps, NYT, 3.1.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/03/us/03foodstamps.html

The Safety Net

Across U.S.,

Food Stamp Use Soars

and Stigma Fades

November 29, 2009

The New York Times

By JASON DePARLE

and ROBERT GEBELOFF

MARTINSVILLE, Ohio — With food stamp use at record highs and climbing every

month, a program once scorned as a failed welfare scheme now helps feed one in

eight Americans and one in four children.

It has grown so rapidly in places so diverse that it is becoming nearly as

ordinary as the groceries it buys. More than 36 million people use inconspicuous

plastic cards for staples like milk, bread and cheese, swiping them at counters

in blighted cities and in suburbs pocked with foreclosure signs.

Virtually all have incomes near or below the federal poverty line, but their

eclectic ranks testify to the range of people struggling with basic needs. They

include single mothers and married couples, the newly jobless and the

chronically poor, longtime recipients of welfare checks and workers whose

reduced hours or slender wages leave pantries bare.

While the numbers have soared during the recession, the path was cleared in

better times when the Bush administration led a campaign to erase the program’s

stigma, calling food stamps “nutritional aid” instead of welfare, and made it

easier to apply. That bipartisan effort capped an extraordinary reversal from

the 1990s, when some conservatives tried to abolish the program, Congress

enacted large cuts and bureaucratic hurdles chased many needy people away.

From the ailing resorts of the Florida Keys to Alaskan villages along the Bering

Sea, the program is now expanding at a pace of about 20,000 people a day.

There are 239 counties in the United States where at least a quarter of the

population receives food stamps, according to an analysis of local data

collected by The New York Times.

The counties are as big as the Bronx and Philadelphia and as small as Owsley

County in Kentucky, a patch of Appalachian distress where half of the 4,600

residents receive food stamps.

In more than 750 counties, the program helps feed one in three blacks. In more

than 800 counties, it helps feed one in three children. In the Mississippi River

cities of St. Louis, Memphis and New Orleans, half of the children or more

receive food stamps. Even in Peoria, Ill. — Everytown, U.S.A. — nearly 40

percent of children receive aid.

While use is greatest where poverty runs deep, the growth has been especially