|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Architecture, Cities > Towers

Men are almost

absent ...

neighbours

socialising on the upper floor deck in 1961.

Photograph:

Rights

Managed/Roger Mayne Archive/Mary Evans Picture Library

Love Among the

Ruins review

– beauty and

brilliance on the high-rises of Sheffield

G

Mon 23 Jul 2018 10.45 BST

Last modified on

Mon 23 Jul 2018 10.46 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jul/23/

love-among-the-ruins-review-roger-mayne-bill-stephenson-photos-sheffield-estates

UK > skyscraper

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/20/

realestate/shrewsbury-worlds-first-skyscraper-england.html

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/sep/20/

only-way-is-up-for-towers-that-touch-the-sky-in-pictures

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/aug/13/

london-office-evolution-lloyds-leadenhall-cheesegrater

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/nov/12/

one-world-trade-center-tallest-building

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/interactive/2013/feb/01/

view-from-top-shard-london-interactive

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/jan/13/

renzo-piano-shard-interview-observer

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/nov/23/

shard-britain-tallest-building

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/oct/13/

skyscrapers-signal-downturn

http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/2009/oct/01/

chicago-architecture-olympics-2016

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/dec/27/

architecture.communities

USA >

skyscraper

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/29/

arts/design/new-york-virtual-tour-virus.html

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/23/

716284808/new-york-city-lawmakers-pass-landmark-climate-measure

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/29/

technology/salesforce-tower-san-francisco-skyline.html

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2016/jul/20/

skyscraper-city-manhattan-how-built-new-york-public-library-

in-pictures

- Guardian pictures gallery

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/05/

magazine/new-york-life.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/16/nyregion/

arthur-g-cohen-real-estate-developer-is-dead-at-84.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/30/realestate/commercial/

the-superman-building-in-providence-now-dark-

is-in-need-of-a-savior.html

city skyline / skyline

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2025/apr/11/

the-week-around-the-world-in-20-pictures#img-10

https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2023/jun/07/

smoke-photos-us-wildfires-canada-new-york-toronto

- Guardian picture gallery

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/

architecture-design-blog/2014/may/05/

londons-top-10-towers

skyline USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/13/

business/central-london-office-space.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/29/

technology/salesforce-tower-san-francisco-skyline.html

spring up

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/dec/27/

architecture.communities

The 10 best tall buildings - in pictures

UK 2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/gallery/2011/apr/17/

ten-best-tall-buildings

the world's tallest building

the tallest tower in the world

tower

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/

from-the-archive-blog/gallery/2018/may/16/

ronan-point-tower-collapse-may-1968

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/

architecture-design-blog/2014/may/05/londons-

top-10-towers

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/apr/29/

top-10-worst-london-

skyscrapers-quill-odalisk-walkie-talkie

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jan/30/

shard-renzo-piano-london-bridge

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/nov/23/

shard-britain-tallest-building

tower USA

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/05/

super-tall-super-skinny-super-expensive-

the-pencil-towers-of-new-yorks-super-rich

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/05/

magazine/new-york-life.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/16/nyregion/

arthur-g-cohen-real-estate-developer-is-dead-at-84.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/19/

realestate/rising-tower-in-manhattan-takes-on-sheen-

as-billionaires-haven.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/08/nyregion/

08names.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/23/

arts/design/23ouro.html

USA > NYC >

needle-like tower / pencil tower UK

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/05/

super-tall-super-skinny-super-expensive-

the-pencil-towers-of-new-yorks-super-rich

bullet-shaped office tower

USA > The Sears Tower in

Chicago

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/jun/25/

sears-towers-chicago-green-renovation

high-rise towers

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/gallery/2017/oct/12/

life-in-the-block-high-rise-living-in-london-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/16/

grenfell-tower-price-britain-inequality-high-rise

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/15/

high-rise-towers-are-safe-but-tougher-inspections-needed-say-experts

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/15/

experts-warned-government-against-cladding-material-used-on-grenfell

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/video/2017/jun/14/

grenfell-fire-people-community-video

high-rise building

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

hud-demolishes-public-housing-displaces-residents-cairo - November 23, 2022

high-rise dwellers

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/16/

grenfell-tower-price-britain-inequality-high-rise

penthouse / sky-high apartments

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/

realestate/another-real-estate-record-go-figure.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/26/

nyregion/ken-griffin-238-million-penthouse.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/realestate/

adding-penthouses-for-profit.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/12/realestate/

paying-a-premium-for-sky-high-apartments.html

USA > art deco tower

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/18/

realestate/17-million-home-in-art-deco-chelsea-tower.html

USA > New York's twin

towers UK

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/20/

world-trade-center-twin-towers-new-york-911-history-cities-day-40

USA > tower > One World Trade Center

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/nov/12/

one-world-trade-center-tallest-building

tower blocks

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2014/apr/20/

a-scottish-tall-storey-reprieve-in-pictures

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/video/2012/jun/11/

glasgows-red-road-tower-demolished-video

tower

over N

World Trade Center / The Twin

Towers USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/16/

world-trade-center-may-be-isolated-again-this-time-by-security-measures/

https://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/30/

world-trade-center-tower-tallest-building

the fallen twin towers

USA

1,776 feet

USA

NYC, USA > Freedom Tower

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/30/

world-trade-center-tower-tallest-building

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/jul/05/

september11.usa

USA > Chicago's Aqua Tower

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/oct/20/

aqua-tower-jeanne-gang

British giant Aedas

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/dec/18/

aedas-number-one-architecture-practice

watchtowers UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/may/13/

architecture.photography

high-rise / highrise

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/projects/2013/

high-rise/

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/08/nyregion/

08names.html

high-rise housing

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2008/dec/28/

communities-planning

USA >

NYC > Manhattan's skyline

Bruce Castle Park in Tottenham, north London >

Tudor water tower

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/aug/02/

1

overtake

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/30/

world-trade-center-tower-tallest-building

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/gallery/2012/apr/30/

one-world-trade-centre-new-york-in-pictures

spire

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/05/

magazine/new-york-life.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/24/us/

as-its-economy-grows-charleston-is-torn-over-its-architectural-future.html

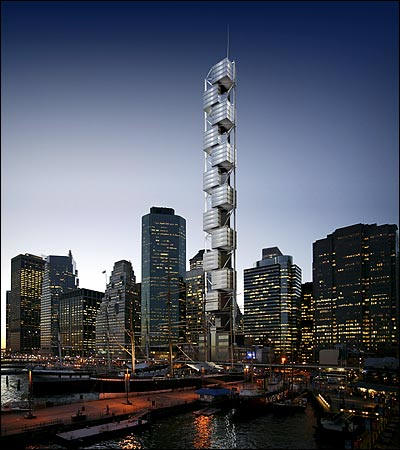

Santiago Calatrava S.A.

A residential tower on South Street.

An Architect Embraces New York

By

ROBIN POGREBIN

NYT

April 23, 2005

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/23/

arts/design/an-architect-embraces-new-york.html

Photograph:

Bess Greenberg/The New York Times

Ariel East, on Broadway near 100th Street in Manhattan.

Following a trend, it

is named for a moon of Uranus.

To Name Towers in the Sky, Many Look There for Inspiration

NYT

8 July 2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/08/

nyregion/08names.html

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Architecture, Cities

High-Rises, Towers, Skyscrapers

To Name

Towers in the Sky,

Many Look There for Inspiration

July 8, 2008

The New York Times

By MICHAEL BARBARO

They are advertised as one-of-a-kind homes in the air.

But the floor-to-ceiling glass towers popping up in record numbers across New

York City are starting to sound an awful lot alike.

Two new high-rises, one on the Upper East Side, the other in Brooklyn, a have

the same name: Azure, a deep shade of blue. Seem familiar? It should. On the

Lower East Side, another new building is called Blue.

Sky House, under construction on East 29th Street, is not to be confused with

the Cielo (Italian for “sky”), on East 83rd Street. And then there are Star

Tower, in Long Island City, and Solaria, in the Bronx.

It is an unintended consequence of the city’s historic building boom: a traffic

jam of similar sounding names. To showcase the sweeping views from buildings

with huge, wrap-around windows, real estate developers are flocking to a set of

words that evoke the sky, clouds and stars.

Builders say there are only so many ways to describe a glass box, the undisputed

architectural aesthetic of the moment. Similar names, they argue, are

inevitable.

But several acknowledged that the fixation with all things celestial could

backfire. “The danger is that they start to sound the same,” said Nancy Packes,

president of Brown Harris Stevens Project Marketing, which helped name Azure on

the Upper East Side.

At least four new buildings, for example, are named for objects in the night

sky: Orion, Lucida (the brightest star in a constellation), Ariel (a moon of

Uranus) and South Star.

“Many of these names are really bumping into each other,” said David J. Wine,

vice chairman of Related Companies, a major developer in the city, which has

favored traditional-sounding names, like the Brompton, for a luxury condominium

under construction on the Upper East Side.

“It is a bit surprising,” he added.

Trends in New York building names are not new. Builders seized on the American

West around 1900, producing the Wyoming, on West 55th Street, a block away from

the Oregon, on West 54th, and across the park from the Idaho, on East 48th. And,

of course, there is the Dakota, on West 72nd Street.

Soon after, a wave of Francophilia yielded the Bordeaux, the Cherbourg and the

Paris. Native American motifs were enshrined in the Iroquois, the Seminole and

the Waumbek.

Trees (Laurel), Greek mythology (Helena) and Spanish cities (Madrid) have all

woven their way into the city’s skyline.

And mailing addresses are often used as building names, especially when the

street is considered prestigious, like Park Avenue or Perry Street, in the West

Village.

Occasionally, names flop. When developers converted the Stanhope Hotel, across

from the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue, into luxury apartments two

years ago, they called the project the Stanhope. Few takers emerged, and the

name was discarded in favor of the street address, 995 Fifth Avenue.

What is striking about the latest wave is just how closely — or haphazardly —

some of the names overlap.

The goal, after all, in a crowded real estate market like New York, is to stand

out, not to blend in, said Mr. Wine, of Related. Most of the units in the new

towers go for $1 million or more.

“You need to be distinctive,” he said, “and a good name can do that.”

A building’s name is so important that developers spend months deliberating over

it. People involved in the process describe it as the most intense, emotional

and combative phase of a building’s development.

The name must at once convey an image — trendy or traditional, luxurious or

affordable — it must be catchy and, of course, it must be memorable.

Developers generally start with a list of more than 100 names and, working with

marketing experts, advertising executives and graphic artists, slowly whittle

them down to one. The winner becomes the centerpiece of a marketing campaign,

typically costing millions and including newspaper advertisements, Web sites,

glossy advertorials and sales centers.

The group charged with naming a condominium on Norfolk Street on the Lower East

Side began with 300 possibilities. The 16-story building, which is cantilevered,

is wrapped in five shades of blue glass. Everyone agreed that blue would be in

the final name, said Barrie Mandel, senior vice president at Corcoran Group

Marketing, which is promoting the building.

But the debate did not end there. “We thought about La Blue, about Azure, but

those names were way too cutesy for such a gritty neighborhood,” she said. In

the end, they settled on the unembellished Blue.

A similar debate raged among the developer, the marketing firm and the ad agency

for a building at 91st Street and First Avenue. It is 34 stories tall, with

wall-to-wall windows on all sides, and prices for the homes there are expected

to range from $605,000 to $4.8 million.

The developer said the majority of the building’s apartments would have views of

the skyline on three sides or the river to the east, a rarity in that

neighborhood. “The thing both those carry in common — river views and sky views

— is blue,” said Ms. Packes, of Brown Harris Stevens Project Marketing.

Ms. Packes said the team working on the building thought the name Blue, on its

own, was “too blunt,” adding: “It wouldn’t be very suitable for family residence

on the Upper East Side.”

So they picked a synonym: Azure. “It just is a classier way of saying blue,”

said Luis Vazquez, director of sales for the building.

The resemblance between Blue and the two Azures was pure coincidence, said Ms.

Packes, who said she was certain buyers would see them as distinct. “The test is

confusion,” she said. “When you are in different neighborhoods, it minimizes the

possibility of confusion.”

Matt Parrella, the broker at the Corcoran Group working on the other Azure, in

the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, said the developer did not realize

the building shared a name with another apartment building “until after the

fact.”

Glass-encased residential buildings like Azure and Blue have existed in New York

for decades, but over the last five years they have started to dominate new

construction.

Developers say that buyers prize height and views above nearly all else and that

a building’s name is the best way to communicate those amenities.

“That is what people pay for: views, light, sky, air,” said Louise Sunshine,

development director at Alexico Group, a developer. “That is why there is such a

huge emphasis on that in these names.”

Alexico is finishing a building on East 67th Street that was intended to be a

glass tower. But the developer changed its mind and created a limestone exterior

instead. The project’s original name? Celeste, in honor of its views of the

stars, Ms. Sunshine said. It is now called the Laurel.

It is not clear who started the heavenly naming trend, but a developer called

Extell is happy to take credit. The firm is building several new projects in

Manhattan named after stars, like Lucida, at 85th Street and Lexington Avenue.

Raizy Haas, a senior vice president at Extell, said the star theme captured the

appearance of the firm’s buildings, especially at night, when its glass walls,

suffused with light, glow like stars. She said the company was “flattered” to

see rival developers follow Extell’s designs and names, “But sometimes we think,

‘Why couldn’t they be more creative and not copy us?’

To Name Towers in the

Sky, Many Look There for Inspiration,

NYT,

8.7.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/08/

nyregion/08names.html

French Architect Wins Pritzker Prize

March 31, 2008

The New York Times

By ROBIN POGREBIN

Jean Nouvel, the bold French architect known for such wildly

diverse projects as the muscular Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and the

exotically louvered Arab World Institute in Paris, has received architecture’s

top honor, the Pritzker Prize.

Mr. Nouvel, 62, is the second French citizen to take the prize, awarded annually

to a living architect by a jury chosen by the Hyatt Foundation. (Christian de

Portzamparc of France won in 1994.) His selection is to be announced Monday.

“For over 30 years Jean Nouvel has pushed architecture’s discourse and praxis to

new limits,” the Pritzker jury said in its citation. “His inquisitive and agile

mind propels him to take risks in each of his projects, which, regardless of

varying degrees of success, have greatly expanded the vocabulary of contemporary

architecture.”

In extending that vocabulary Mr. Nouvel has defied easy categorization. His

buildings have no immediately identifiable signature, like the curves of Frank

Gehry or the light-filled atriums of Renzo Piano. But each is strikingly

distinctive, be it the Agbar Tower in Barcelona (2005), a candy-colored,

bullet-shaped office tower, or his KKL cultural and congress center in Lucerne,

Switzerland (2000), with a slim copper roof cantilevered delicately over Lake

Lucerne.

“Every time I try to find what I call the missing piece of the puzzle, the right

building in the right place,” Mr. Nouvel said this month over tea at the Mercer

Hotel in SoHo.

Yet he does not design buildings simply to echo their surroundings. “Generally,

when you say context, people think you want to copy the buildings around, but

often context is contrast,” he said.

“The wind, the color of the sky, the trees around — the building is not done

only to be the most beautiful,” he said. “It’s done to give advantage to the

surroundings. It’s a dialogue.”

The prize, which includes a $100,000 grant and a bronze medallion, is to be

presented to Mr. Nouvel on June 2 in a ceremony at the Library of Congress in

Washington.

Among Mr. Nouvel’s New York buildings are 40 Mercer, a 15-story red-and-blue,

glass, wood and steel luxury residential building completed last year in SoHo,

and a soaring 75-story hotel-and-museum tower with crystalline peaks that is to

be built next to the Museum of Modern Art in Midtown. Writing in The New York

Times in November, Nicolai Ouroussoff said the Midtown tower “promises to be the

most exhilarating addition to the skyline in a generation.”

Born in Fumel in southwestern France in 1945, Mr. Nouvel originally wanted to be

an artist. But his parents, both teachers, wanted a more stable life for him, he

said, so they compromised on architecture.

“I realized it was possible to create visual compositions” that, he said, “you

can put directly in the street, in the city, in public spaces.”

At 20 Mr. Nouvel won first prize in a national competition to attend the École

des Beaux-Arts in Paris. By the time he was 25 he had opened his own

architecture firm with François Seigneur; a series of other partnerships

followed.

Mr. Nouvel cemented his reputation in 1987 with completion of the Arab World

Institute, one of the “grand projects” commissioned during the presidency of

François Mitterrand. A showcase for art from Arab countries, it blends high

technology with traditional Arab motifs. Its south-facing glass facade, for

example, has automated lenses that control light to the interior while also

evoking traditional Arab latticework. For his boxy, industrial Guthrie Theater,

which has a cantilevered bridge overlooking the Mississippi River, Mr. Nouvel

experimented widely with color. The theater is clad in midnight-blue metal; a

small terrace is bright yellow; orange LED images rise along the complex’s two

towers.

In its citation, the Pritzker jury said the Guthrie, completed in 2006, “both

merges and contrasts with its surroundings.” It added, “It is responsive to the

city and the nearby Mississippi River, and yet, it is also an expression of

theatricality and the magical world of performance.”

The bulk of Mr. Nouvel’s commissions work has been in Europe however. Among the

most prominent is his Quai Branly Museum in Paris (2006), an eccentric jumble of

elements including a glass block atop two columns, some brightly colorful boxes,

rust-colored louvers and a vertical carpet of plants. “Defiant, mysterious and

wildly eccentric, it is not an easy building to love,” Mr. Ouroussoff wrote in

The Times.

A year later he described Mr. Nouvel’s Paris Philharmonie concert hall, a series

of large overlapping metal plates on the edge of La Villette Park in

northeastern Paris, as “an unsettling if exhilarating trip into the unknown.”

Mr. Nouvel has his plate full at the moment. He is designing a satellite of the

Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates, giving it a shallow

domed roof that creates the aura of a just-landed U.F.O. He recently announced

plans for a high-rise condominium in Los Angeles called SunCal tower, a narrow

glass structure with rings of greenery on each floor. His concert hall for the

Danish Broadcasting Corporation is a tall rectangular box with transparent

screen walls.

Before dreaming up a design, Mr. Nouvel said, he does copious research on the

project and its surroundings. “The story, the climate, the desires of the

client, the rules, the culture of the place,” he said. “The references of the

buildings around, what the people in the city love.”

“I need analysis,” he said, noting that every person “is a product of a

civilization, of a culture.” He added: “Me, I was born in France after the

Second World War. Probably the most important cultural movement was

Structuralism. I cannot do a building if I can’t analyze.”

Although he becomes attached to his buildings, Mr. Nouvel said, he understands

that like human beings, they grow and change over time and may even one day

disappear. “Architecture is always a temporary modification of the space, of the

city, of the landscape,” he said. “We think that it’s permanent. But we never

know.”

French Architect Wins

Pritzker Prize, NYT, 31.3.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/31/arts/design/31prit.html

Architecture

In Plans for Railyards,

a Mix of Towers and Parks

November 24, 2007

The New York Times

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

The West Side railyards are the kind of urban development project that makes

builders dance in the streets. A footprint bigger than Rockefeller Center’s and

the potential for more commercial and residential space than ground zero: what

more could an urban visionary want?

So the five proposals recently unveiled by the Metropolitan Transportation

Authority to develop the 26-acre Manhattan railyards are not just a

disappointment for their lack of imagination, they are also a grim referendum on

the state of large-scale planning in New York City.

With the possible exception of a design for the Extell Development Company, the

proposals embody the kind of tired, generic planning formulas that appear

wherever big development money is at stake. When thoughtful architecture

surfaces at all, it is mostly a superficial gloss of culture, rather than a

sincere effort to come to terms with the complex social and economic changes the

city has been undergoing for the last decade or so.

Located on six square blocks between 30th and 33rd Streets and 10th Avenue and

the West Side Highway, the yards are one of the few remaining testaments to New

York’s industrial past. Dozens of tracks leading in and out of Pennsylvania

Station carve through the site. A string of parking lots and old industrial

buildings flanks the tracks to the south; the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center

is a block to the north. To build, developers first will have to create a

platform over the tracks, at an estimated cost of $1.5 billion; construction of

the platform and towers has to take place without interrupting train service.

City officials and the transportation authority, which owns the railyards, have

entertained various proposals for the site in recent years, including an

ill-conceived stadium for the Jets. The current guidelines would allow up to 13

million square feet of commercial, retail and residential space; a building to

house a cultural group yet to be named; and a public park.

All five of the development teams chose to arrange the bulk of the towers at the

northern and southern edges of the site, to minimize disruption of the tracks

below, and concentrated the majority of the commercial towers to the east, and

the residential towers to the west, where they would have views of the Hudson

River.

But none of the teams have fully explored the potentially rich relationship

between the railyards and the development above them, an approach that could

have added substance to the plans. Nor did any find a successful way to come to

terms with the project’s gargantuan scale.

The proposal by the Related Companies would transform the site into a virtual

theme park for Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, the developer’s main tenant.

The design, by a team of architects that includes Kohn Pedersen Fox,

Arquitectonica and Robert A. M. Stern, would be anchored at its eastern end by a

74-story tower. Three slightly smaller towers would flank it, creating an

imposing barrier between the public park and the rest of the city to the east.

The plan also includes a vast retail mall and plaza between 10th and 11th

Avenues, which could be used by News Corporation for advertising, video

projections and outdoor film and concert events — a concept that would

essentially transform what is being hailed as a public space into a platform for

corporate self-promotion. A proposal by FXFowle and Pelli Clarke Pelli for the

Durst Organization and Vornado Realty Trust is slightly less disturbing.

Following a similar plan, it would be anchored by a new tower for Condé Nast

Publications to the north, and a row of residential towers extending to the

west. Sinuous, elevated pedestrian walkways would wind their way through the

site just above the proposed public park. The walkways are meant to evoke a

contemporary version of the High Line, the raised tracks being converted into a

public garden just to the south. But their real precedents are the deadening

elevated streets found in late Modernist housing complexes.

By comparison, the proposal by Tishman Speyer Properties, designed by Helmut

Jahn, at least seems more honest. The site is anchored by four huge towers that

taper slightly as they rise, exaggerating their sense of weight and recalling

more primitive, authoritarian forms: you might call it architecture of

intimidation. As you move west, a grand staircase leads down to a circular plaza

that would link the park to a pedestrian boulevard the city plans to construct

from the site north toward 42nd Street.

Mr. Jahn built his reputation in the 1980s and ’90s, when many modern architects

were struggling to pump energy into work that had become cold and alienating.

Over all, the design looks like a conventional 1980s mega-development: an oddly

retro vision of uniform glass towers set around a vast plaza decorated with a

few scattered cafes. (In a rare nice touch, Mr. Jahn allows some of his towers

to cantilever out over the deck of the High Line, playing up the violent clash

between new and old.)

Another proposal, by Brookfield Properties, is an example of how real

architectural talent can be used to give a plan an air of sophistication without

adding much substance. Brookfield has included a few preliminary sketches of

buildings by architectural luminaries like Diller Scofidio & Renfro and the

Japanese firm Kazuyo Sejima & Ryue Nishizawa, but the sketches are nothing more

than window dressing. The proposal includes a retail mall and commercial towers

along 10th Avenue, which gives the public park an isolated feel. A hotel and

retail complex cuts the park in two, so that you lose the full impact of its

sweep.

For those who place urban-planning issues above dollars and cents, the Extell

Development Company’s proposal is the only one worth serious consideration.

Designed by Steven Holl Architects of New York, the plan tries to minimize the

impact of the development’s immense scale. Most of the commercial space would be

concentrated in three interconnecting towers on the northeast corner of the

site. The towers’ forms pull apart and join together as they rise — an effort to

break down their mass in the skyline. Smaller towers flank the site’s southern

edge, their delicate, shardlike forms designed to allow sunlight to spill into

the park area. A low, 10-story commercial building to the north is lifted off

the ground on columns to allow the park to slip underneath and connect to 33rd

Street.

The plan’s most original feature is a bridgelike cable structure that would span

the existing tracks and support a 19-acre public park. According to the

developer, the cable system would reduce the cost of building over the tracks

significantly, allowing the density to be reduced to 11.3 million square feet

from 13 million and still make a profit. The result would be both a more

generous public space and a less brutal assault on the skyline. It is a

sensitive effort to blend the development into the city’s existing fabric.

But what is really at issue here is putting the importance of profit margins

above architecture and planning. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority could

have pushed for more ambitious proposals. For decades now cities like Barcelona

have insisted on a high level of design in large-scale urban-planning projects,

and they have done so without economic ruin.

By contrast, the authority is more likely to focus on potential tenants like

News Corporation and Condé Nast and the profits they can generate than on the

quality of the design. A development company like Extell is likely to be

rejected outright as too small to handle a project of this scale, however

original its proposal. (In New York dark horse candidates often find that

ambitious architectural proposals are one of the few ways to compete with bigger

rivals.)

This is not how to build healthy cities. It is a model for their ruin, one that

has led to a parade of soulless developments typically dressed up with a bit of

parkland, a few commercial galleries and a token cultural institution — the

superficial gloss of civilization. As an ideal of urbanism, it is hollow to its

core.

In Plans for Railyards,

a Mix of Towers and Parks,

NYT,

24.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/24/arts/design/24huds.html

Architecture Review

Pride and Nostalgia

Mix in The Times’s New Home

November 20, 2007

The New York Times

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

Writing about your employer’s new building is a tricky task. If I love it,

the reader will suspect that I’m currying favor with the man who signs my

checks. If I hate it, I’m just flaunting my independence.

So let me get this out of the way: As an employee, I’m enchanted with our new

building on Eighth Avenue. The grand old 18-story neo-Gothic structure on 43rd

Street, home to The New York Times for nearly a century, had its sentimental

charms. But it was a depressing place to work. Its labyrinthine warren of desks

and piles of yellowing newspapers were redolent of tradition but also seemed an

anachronism.

The new 52-story building between 40th and 41st Streets, designed by the Italian

architect Renzo Piano, is a paradise by comparison. A towering composition of

glass and steel clad in a veil of ceramic rods, it delivers on Modernism’s

age-old promise to drag us — in this case, The Times — out of the Dark Ages.

I enjoy gazing up at the building’s sharp edges and clean lines when I emerge

from the subway exit at 40th Street and Seventh Avenue in the morning. I love

being greeted by the cluster of silvery birch trees in the lobby atrium, their

crooked trunks sprouting from a soft blanket of moss. I even like my

fourth-floor cubicle, an oasis of calm overlooking the third-floor newsroom.

Yet the spanking new building is infused with its own nostalgia.

The last decade has been a time of major upheaval in newspaper journalism, with

editors and reporters fretting about how they should adapt to the global digital

age. In New York that anxiety has been compounded by the terrorist attacks of

2001, which prompted many corporations to barricade themselves inside gilded

fortresses.

Mr. Piano’s building is rooted in a more comforting time: the era of corporate

Modernism that reached its apogee in New York in the 1950s and 60s. If he has

gently updated that ethos for the Internet age, the building is still more a

paean to the past than to the future.

What makes a great New York skyscraper? The greatest of them tug at our

heartstrings. We seek them out in the skyline, both to get our bearings and to

anchor ourselves psychologically in the life of the city.

Mr. Piano’s tower is unlikely to inspire that kind of affection. The building’s

most original feature is a scrim of horizontal ceramic rods that diffuses

sunlight and lends the exterior a clean, uniform appearance. Mr. Piano used a

similar screening system for his 1997 Debis Tower for Daimler-Benz in Berlin, to

mixed results. For The Times, he spent months adjusting the rods’ color and

scale, and in the early renderings they had a lovely, ethereal quality.

Viewed from a side street today, they have the precision and texture of a finely

tuned machine. But despite the architect’s best efforts, the screens look flat

and lifeless in the skyline. The uniformity of the bars gives them a slightly

menacing air, and the problem is compounded by the battleship gray of the

tower’s steel frame. Their dull finish deprives the facades of an enlivening

play of light and shadow.

The tower’s crown is also disappointing. To hide the rooftop’s mechanical

equipment and create the impression that the tower is dissolving into the sky,

Mr. Piano extended the screens a full six stories past the top of the building’s

frame. Yet the effect is ragged and unfinished. Rather than gathering momentum

as it rises, the tower seems to fizzle.

But if the building is less than spectacular in the skyline, it comes to life

when it hits the ground. All of Mr. Piano’s best qualities are in evidence here

— the fine sense of proportion, the love of structural detail, the healthy sense

of civic responsibility.

The architect’s goal is to blur the boundary between inside and out, between the

life of the newspaper and the life of the street. The lobby is encased entirely

in glass, and its transparency plays delightfully against the muscular steel

beams and spandrels that support the soaring tower.

People entering the building from Eighth Avenue can glance past rows of elevator

banks all the way to the fairy tale atrium garden and beyond, to the plush red

interior of TheTimesCenter auditorium. From the auditorium, you gaze back

through the trees to the majestic lobby space. In effect, the lobby itself is a

continuous public performance.

The sense of transparency is reinforced by the people streaming through the

lobby. The flow recalls the dynamic energy of Grand Central Terminal’s Great

Hall or the Rockefeller Center plaza, proud emblems of early-20th-century

mobility.

Architecturally, however, The New York Times Building owes its greatest debt to

postwar landmarks like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s Lever House or Mies van der

Rohe’s Seagram Building — designs that came to embody the progressive values and

industrial power of a triumphant America. Their streamlined glass-and-steel

forms proclaimed a faith in machine-age efficiency and an open, honest,

democratic society.

Newspaper journalism, too, is part of that history. Transparency, independence,

the free flow of information, moral clarity, objective truth — these notions

took hold and flourished in the last century at papers like The Times. To many

this idealism reached its pinnacle in the period stretching from the civil

rights movement to the Vietnam War to Watergate, when journalists grew

accustomed to speaking truth to power, and the public could still accept

reporters as impartial observers.

This longing for an idealistic time permeates the main newsroom. Pierced by a

double-height skylight well on the third and fourth floors, the newsroom has a

cool, insular feel even as the facades of the surrounding buildings press in

from the north and south. The well functions as a center of gravity, focusing

attention on the paper’s nerve center. From many of the desks you also enjoy a

view of the delicate branches of the atrium’s birch trees.

Internal staircases link the various newsroom floors to encourage interaction.

The work cubicles are flanked by rows of glass-enclosed offices, many of which

are unassigned so that they can be used for private phone conversations or

spontaneous meetings. Informal groupings of tables and chairs are also scattered

about, creating a variety of social spaces.

From the higher floors, which house the corporate offices of The Times and 22

floors belonging to the developer Forest City Ratner, the views become more

expansive. Cars rush up along Eighth Avenue. Billboards and electronic signs

loom from all directions. By the time you reach the 14th-floor cafeteria, the

entire city begins to come into focus, with dazzling views to the north, south,

east and west. A long, narrow balcony is suspended within the cafeteria’s

double-height space, reinforcing the impression that you’re floating in the

Midtown skyline.

Many of my colleagues complained about the building at first. There’s too much

empty space in the newsroom, some groused; they missed the intimacy of the old

one. The glass offices look sterile, and no one will use them, some said.

I suspect they’ll all adjust. One of the joys of working in an ambitious new

building is that you can watch its personality develop. From week to week, you

see more and more lone figures chatting on cellphones in the small glass offices

with their feet atop a table. And even my grumpiest colleagues now concede that

a little sunlight and fresh air are not a bad thing.

Even so, you never feel that the building embraces the future wholeheartedly.

Rather than move beyond the past, Mr. Piano has fine-tuned it. The most

contemporary features — the computerized louvers and blinds that regulate the

flow of light into the interiors — are technological innovations rather than

architectural ones; the regimented rows of identical wood-paneled cubicles

chosen by the interior design firm Gensler could be a stage set for a 2007

remake of “All the President’s Men,” minus the 1970s hairstyles.

Maybe this accounts for the tower’s slight whiff of melancholy.

Few of today’s most influential architects buy into straightforward notions of

purity or openness. Having witnessed an older generation’s mostly futile quest

to effect social change through architecture, they opt for the next best thing:

to expose, through their work, the psychic tensions and complexities that their

elders sublimated. By bringing warring forces to the surface, they reason, a

building will present a franker reading of contemporary life.

Journalism, too, has moved on. Reality television, anonymous bloggers, the

threat of ideologically driven global media enterprises — such forces have

undermined newspapers’ traditional mission. Even as journalists at The Times

adjust to their new home, they worry about the future. As advertising inches

decline, the paper is literally shrinking; its page width was reduced in August.

And some doubt that newspapers will even exist in print form a generation from

now.

Depending on your point of view, the Times Building can thus be read as a

poignant expression of nostalgia or a reassertion of the paper’s highest values

as it faces an uncertain future. Or, more likely, a bit of both.

Pride and Nostalgia Mix

in The Times’s New Home, NYT, 20.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/20/arts/design/20time.html

Skyscrapers spring up

in response to rising

demand

Wednesday December 27, 2006

Guardian

Karen McVeigh

They sound more like theme park rides than

symbols of progress, but towers such as the cheese-grater, the walkie-talkie and

the helter-skelter are leading a renaissance in British high-rise architecture.

Cities vying for the buildings with the best

superlatives - the tallest residential tower, the highest viewing platform -

include London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Brighton and

Edinburgh.

By 2010 London's skyline will be dominated by the London Bridge Tower, which at

310 metres (1,017ft) will take over from Canary Wharf's 235-metre structure at

No 1 Canada Square as the tallest building in Europe. But it is unlikely to be

on its own for long. Work is also planned on the Bishopsgate Tower (or

helter-skelter) and at least four other skyscrapers in the City and Canary Wharf

next year.

The rapid surge in planning applications for skyscrapers has left some

authorities unprepared.

Leeds, which will be home to the 171-metre Lumiere, has more than 20 plans in

the pipeline and is drawing up a tall buildings policy.

Edinburgh, with many of its key tourist attractions in World Heritage sites, is

also wrestling with threats to its famous skyline. The council, currently

dealing with a planning application for a 175-metre, 18-storey development on

its waterfront, is drawing up a plan to stop further encroachments.

Work on Brighton's answer to the London Eye is due to begin next year, despite

local protests. At 183 metres, the i-360 is almost twice the size of the town's

24-storey Sussex Heights.

In what is a far cry from the bad old days of the concrete blocks of the 1960s

and 70s, the new high-rises can command extravagant rents, often costlier the

higher up you go.

Prices for a luxury apartment in Manchester's 169-metre Beetham Tower range from

£100,000 to £2.5m, and all were sold within 12 months of being offered. In

London, a small apartment in Canary Wharf was recently bought for £5m, and the

rest of the tower was snapped up in a matter of weeks.

"People could live in a mansion block in Belgravia for that money but they want

to live in these buildings," said James Newman of skyscrapernews.com. "Why

commute from Surrey when you can live 10 minutes' walk from work?"

The mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, said he expected to see an average of one

very tall building being constructed every year in Canary Wharf and the City to

encourage major companies to base their offices there.

Skyscrapers spring up in response to rising demand, G, 27.12.2006,

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/dec/27/

architecture.communities

Architecture Review

Norman Foster's New Hearst Tower

Rises From

Its 1928 Base

June 9, 2006

The New York Times

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

NEW YORK architecture has suffered a lot in

recent years. The brief optimism born of a public rebellion against early

proposals for ground zero has long since given in to cynicism. Since then it has

often seemed that fear and melancholy have swamped our creative confidence.

Norman Foster's new Hearst Tower arrives just in time, slamming through the

malaise like a hammer. Crisscrossed by a grid of bold steel cross-braces, its

chiseled glass form rises with blunt force from the core of the old 1928 Hearst

Building on Eighth Avenue, at 57th Street. Past and present don't fit seamlessly

together here; they collide with ferocious energy.

This 46-story tower may be the most muscular symbol of corporate self-confidence

to rise in New York since the 1960's, when Modernism was in full bloom, and most

Americans embraced technological daring as a sure route to social progress.

While fires raged downtown on the afternoon of 9/11, Lord Foster was presenting

his tower to the Hearst Corporation's design committee. Four and a half years

later its opening dovetails with another major success, Renzo Piano's expansion

of the Morgan Library, another sign that the city's energy is reviving.

In some ways the building fulfills a fantasy born in the late 1920's, when

William Randolph Hearst hired Joseph Urban to design a new headquarters building

for his newspaper empire. Although Urban would go on to design the New School

(1930), one of the city's earliest examples of the International style, his

beige cast-concrete Hearst Building is an eclectic fantasy rooted in his early

sensibility as a set designer, mixing fin de siècle Vienna with dashes of Art

Deco. (Hearst had envisioned a soaring tower atop the six-story base, but the

Depression intervened, and the extra floors were never built.)

Part of what makes Lord Foster's building so mesmerizing is a constant shift in

its visual relationship to the skyline. Seen from the south against the backdrop

of the taller and blander glass- and brick-clad towers lining Eighth Avenue, its

stubby crystalline form seems to have been arbitrarily sliced off at the top, so

that it meets the sky abruptly. As you draw nearer, the facade's oversize

triangular windows become disorienting, making the building's scale harder to

grasp.

Once you step into the lobby, the aggressive exterior gives way to a vision that

would fit comfortably in postwar corporate America. Water cascades down an

enormous sloping fountain by the artist Jamie Carpenter at the back of the

lobby. A pair of escalators shoot up from the fountain's edge to a second-floor

cafeteria and exhibition space where a big, dark painting by Richard Long hangs

on the polished black stone wall of the elevator core. The luxurious atmosphere

seems more I.B.M. about 1955 than global media corporation of 2006.

The lobby is a reminder of how far the British architect Lord Foster has

traveled in his long career. In the 1970's he was one of the most visible

practitioners of a high-tech architecture that fetishized machine culture. His

triumphant 1986 Hong Kong and Shanghai bank building, conceived as a

kit-of-parts plugged into a towering steel frame, was capitalism's answer to the

populist Pompidou Center in Paris. Since then his architecture practice has

swollen to more than 700 employees from 65.

Although his work has become sleeker and more predictable in recent years, his

forms are always driven by an internal structural logic. And they treat their

surroundings with a refreshing bluntness. While the exterior of the original

building is intact, for example, all six floors inside have been gutted. What

was once raw concrete is now finished in smooth beige, a stripped stage set for

what Lord Foster calls his "urban plaza."

The project is slightly reminiscent of his 2001 renovation of the British

Museum, in which he enclosed the main courtyard under a glass canopy, treating

what were once exterior facades as interior décor. The results, which blurred

the distinction between new and old, had all the charm of a high-end mall.

Here Lord Foster's approach to history is frank and direct. It's as if the

facades of the original building are really just there to keep out the rain.

A series of enormous steel columns shoots up through the space to support the

tower above. The entire lobby is enclosed under a glass roof, so that as you

look up, you can feel the full sweep of the tower rising above you.

The upper levels are designed with the same clarity. By pushing the elevator

core to the back of the tower, Lord Foster was able to open up the floor plan so

that most offices have sweeping views to the north and south. The building's

exterior diamond-shaped pattern results in lovely canted glass walls in the

corners of each floor that serve as communal areas for office employees. On the

top level a corporate dining room offers a view to the east framed by

two-story-tall triangular braces.

That skyline view made me reflect on the creative arc of so many of New York's

big architectural offices. Fifty years ago, firms like Skidmore, Owings &

Merrill translated the language of European Modernism into a style that became

the progressive face of corporate America. Led by architects like Gordon

Bunshaft, they made some magnificent contributions to the city's skyline, from

the interlocking glass forms of Lever House (1951) to the gently cantilevered

concrete slabs of the 1959 Pepsi-Cola building.

Yet by the late 1970's many of those firms were slumping toward mediocrity,

compromised by an effort to be all things to all people as well as to

incorporate a postmodern pastiche of period styles into their work.

The results are disconcertingly visible from the corporate dining room of the

Hearst Tower. To the north, at Columbus Circle, are the lifeless jagged towers

of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill's recent Time Warner building; a few blocks south

is the firm's hulking beige brick Worldwide Plaza, capped by a dainty copper

pyramid, completed in 1989.

Superficially, the two towers have little in common. Yet both rely on style —

one postmodern, the other contemporary — as a way of cloaking mundane boxes that

add little magic to the skyline and, worse, have a strained relationship to the

streets below. (The curving internal street of the Time Warner tower, a timid

attempt to engage the street life around Columbus Circle, echoes the pointless

circular arcade that surrounds the lobbies at the base of Worldwide Plaza.)

Despite its lingering status, Skidmore lost its way long ago.

Like Skidmore, Lord Foster's firm is a corporate enterprise, boasting branches

in 18 cities. The majority of his clients are commercial. Yet even as his office

grew, Lord Foster consistently managed to stamp all his work with a strong

architectural identity while maintaining a high design standard.

And this is no small feat. In an uncertain age the Hearst Tower is deeply

comforting: a building with confidence in its own values.

Norman Foster's New Hearst Tower Rises From Its 1928 Base,

NYT, 9.6.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/09/arts/design/09hear.html

Norman Foster

Enjoys His First New York

Moment

With the Hearst Tower

June 6, 2006

USA Today

By ROBIN POGREBIN

Norman Foster had reason to be pessimistic

about getting anything built in New York.

His "kissing towers" design for ground zero had been rejected in favor of Daniel

Libeskind's master plan, though it had been voted the public's favorite in 2003.

The same year he was on the verge of presenting his ideas for an overhaul of

Avery Fisher Hall, home of the New York Philharmonic, when the orchestra decided

to leave Lincoln Center for Carnegie Hall. (The move ultimately fell through,

but it set back the Avery Fisher design process.)

Two years before that, the Hearst Corporation's board had scheduled a meeting

for Sept. 12, 2001, to approve his design for a new tower at Eighth Avenue and

57th Street in Manhattan. Naturally, the meeting was put off. Given Hearst's

conservative reputation and the financial uncertainty resulting from the 9/11

attacks, Lord Foster was ready for anything.

"You become really quite philosophical," he said over coffee at the Carlyle

Hotel during a recent visit to New York from Britain. "It's in the nature of

projects. It's in the nature of being an architect. Some projects roll out."

The 46-story Hearst Tower, built atop the company's 1928 headquarters,

ultimately did roll out, and employees have begun moving in. Finally Lord Foster

has wrapped up his first project in New York.

"We came from the outside," said Lord Foster, of Foster & Partners. "We had a

certain sense of conviction about what we should be doing, but the reality was

that we hadn't worked here."

Adding to Lord Foster's hurdles, the original six-story Hearst Building has city

landmark status, and building his steel-and-glass tower, with its distinctive

"diagrid" design, involved negotiations with the city's Landmarks Preservation

Commission.

At 71, Lord Foster is hardly new to such challenges. He rebuilt the Reichstag as

a new German Parliament in Berlin and designed a contemporary great court for

the venerated British Museum. He linked St. Paul's Cathedral to the Tate Modern

with the Millennium Bridge, a slender steel footbridge across the Thames. And he

has repeatedly had to defend his glass enclosure of the courtyard in the

Smithsonian Institution's Old Patent Office Building in Washington.

Preservationists argued that Lord Foster's courtyard would spoil the 1868

building, which is a National Historic Landmark.

But Lord Foster also had reason to approach the Hearst tower with confidence.

Knighted in 1990 and honored in 1999 with the Pritzker Architecture Prize — his

profession's most prestigious award — Lord Foster is considered by many to be

the most prominent architect in Britain.

He is an increasingly strong presence in the United States as well, with a role

in a $5 billion, 66-acre development in the heart of Las Vegas and a commission

for Tower 2 at 200 Greenwich Street, one of the office buildings planned by the

developer Larry A. Silverstein for the World Trade Center site in Lower

Manhattan. Lord Foster is also designing a proposed Globe Theater on the site of

Castle Williams on Governors Island, although that project will vie with many

others.

This architect was warned that he could be in for a rough ride in his project

for the Hearst Corporation, a media company that publishes magazines like

Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and Esquire. "I was told what was possible and

not possible in New York," he said.

Lord Foster thought of the historic cast-concrete exterior of the Hearst

Building as the facade of a town square. "You would have a big plaza, and that

would be part of the sense of the arrival, part of the identity of the

building," he said. In preserving just the old building's shell, Lord Foster

expected to be accused of facade-ism.

"I think it came from everybody who, with the best will in the world, was

seeking to say: 'This is New York. There are certain things that you can do with

a historic building and certain things you can't do. You cannot take the floors

out and gut a building."

His response, he said, was: "Look, you're giving me the responsibility to try to

achieve a tower on this building. If you're charging me with that

responsibility, I think that I should be given the mandate to back my judgment."

There was not enough height between the original floors to create the kind of

offices that Lord Foster said were needed for a company to function effectively

today. "An office space in 1928 is very different from an office space in 2006;

the demands are totally different," he said.

Using the original building would give Hearst "very poky offices," he said,

"with very low ceilings, and everybody saw that as inevitable."

"I felt very uncomfortable with that direction," Lord Foster said, so he moved

the office space up into the tower. "It seemed there ought to be the opportunity

to have a truly celebratory space that would be about the family of Hearst. I

don't mean the Hearst family, I don't mean the management, but actually the

community of the Hearst organization."

So Lord Foster decided to gut the original interior to create a soaring lobby

with a waterfall, a restaurant for the company's 2,000 employees and communal

areas for meetings and receptions. He calls the grand level the building's piano

nobile, evoking the Italian Renaissance notion of a palazzo's "noble floor."

"Every civic building has a principal level," he said. "Traditionally, as you

approach a classical building, you ascend the steps and go up to the principal

level."

The offices were designed for flexibility, so each of Hearst's magazines could

customize its space. "It's the difference between the off-the-rack suit and

something that is really bespoke tailoring," he said.

Frank A. Bennack Jr., Hearst's former chief executive, said Lord Foster took the

time to study the corporation's needs. "Norman has a feel for what it is your

business does," he said. "The dialogue is often not about architecture, but how

does your business function, and how do people live in the space."

The building is also expected to earn certification as the second

environmentally sensitive, or green, office tower in New York. (The first is 7

World Trade Center.) More than 85 percent of the tower's structural steel

contains recycled material, for example, and the building's main level has

radiant floors that are cool in the summer and generate heat in the winter. As a

result of these sustainable virtues, the Hearst Tower is expected to receive a

gold rating from the United States Green Building Council, a coalition of

construction-industry leaders that grades buildings in areas like energy

consumption and indoor-air quality.

As it turned out, the building easily moved through the approval process. In his

recent book, "Reflections" (Prestel Publishing), Lord Foster shares images of

structures that have moved him over the years: the Kasbah in Marrakesh, Morocco;

the Parthenon in Athens; and Frank Lloyd Wright's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

in Manhattan.

In setting out to design the Hearst Tower, Lord Foster said, he thought about

"satisfying the senses, the spirit of the place, the joy of an interplay of

light or shadow or texture or color."

"How the light comes into the equivalent of the town square — that is a value

judgment," he said. "The light meter is going to tell you the level of light.

It's not going to tell you whether the light is going to lift your spirits,

whether it's going to sing."

Norman Foster Enjoys

His First New York Moment With the Hearst Tower,

NYT,

6.6.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/06/

arts/design/06fost.html

At 150 Edgars Lane,

Changing the Idea of

Home

January 2, 2006

The New York Times

By LOUIS UCHITELLE

HASTINGS-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. - The handsome

Tudor-style home at 150 Edgars Lane, built for less than $10,000 in 1925 on a

hillside in this Hudson River town, never seemed to change much through all of

its previous owners. Each family updated the house, but in modest ways until Tom

and Julie Hirschfeld came along.

The Hirschfelds purchased the two-story house with its gabled roof and

stucco-and-wood-beam exterior for $890,000 in the fall of 2002. Good schools,

safe streets, a picturesque community, like-minded neighbors, a relatively short

commute to New York - all these drew the family, just as they drew the previous

owners.

But as home prices have soared in recent years, houses like this one have become

not just nice places to live but remarkably valuable investments as well.

Responding to this newly embedded wealth, the Hirschfelds, like hundreds of

thousands of other families living in suburbs of cities like New York, Chicago

and San Francisco, have transformed their homes into something grander and more

personal.

Tracing the history of the house at 150 Edgars Lane through the decades shows

how the Hirschfelds have broken with the past - and how the idea of what a house

means to a family has changed. Eight different families have lived in this house

for at least a year. Most were middle-income earners in their day: a high school

principal, a typographer, a civil engineer, a psychiatrist, an environmentalist,

small businessmen.

In contrast to the previous owners, the Hirschfelds have poured many thousands

of dollars into renovation, making their home more comfortable and

well-appointed than the earlier owners considered necessary. And more so than

the others, they can certainly afford it.

As the chief operating officer of a hedge fund, Mr. Hirschfeld has plenty of

income to sink into renovation without going into debt. The couple has not held

back. Lifting the house to their standards has become so important to them that

between the purchase price and the outlays for improvements, Mr. Hirschfeld

says, the investment exceeds his home's current market value, estimated at $1.2

million.

Juliet B. Schor, a Boston College sociologist and the author of "The Overspent

American," classifies the burst of spending on home improvement in recent years

as "competitive consumption going on in the top 20 percent of the income

distribution."

But many home owners, the Hirschfelds among them, insist that quite apart from

status and comfort, what was once mainly a dwelling in a compatible suburb now

assumes even greater personal importance in an age when families increasingly

focus on themselves.

"Community is still very important," said William M. Rohe, director of the

Center for Urban and Regional Studies at the University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill. "But homeowners today pay greater attention to the house itself as

an expression of themselves and as a haven for family life."

For the Hirschfelds, a spacious new kitchen wing that juts into the backyard of

their property embodies their sense of how they want their home to enhance their

lives. Finished a year ago, the kitchen has become a gathering place not just

for cooking and meals, but for homework, games, art projects, reading and

conversation with the Hirschfelds' children, Ben, 12, and Leila, 8.

"We didn't build this kitchen for any trophy motivation or to achieve any level

of luxury," Mr. Hirschfeld said, pointing out that the appliances, including the

refrigerator and stove, are ordinary off-the-floor models, not state-of-the-art

extravaganzas. "We did it to make our family life more free-flowing and warm."

The yard was not suitable for the new kitchen wing, however. So a stone

retaining wall went up to carve more flat space from the sloping land -

unexpectedly adding thousands of dollars to renovation costs.

The Hirschfelds also spent more than planned to reverse the deterioration of

their 80-year-old house - one of the tens of thousands built during the nation's

first great suburban housing boom, before the Depression.

"We really bought this to be our family home," Mrs. Hirschfeld said, "and we

made an error in judgment in not knowing what it would cost to deal with the

deterioration." But the basement, she added, which "was wet for 40 years, is no

longer wet."

Before the Hirschfelds, each of the previous owners made incremental

improvements, spreading renovation over their years in residence rather than

bunching it at the beginning. Mostly those earlier owners lived with the house's

shortcomings, including the cramped kitchen, now converted into a mud room.

Wealthy Buyers Move In

The Hirschfelds, in their early 40's, were less constrained by income, an

increasingly common characteristic of the households engaged in home

improvement. Those with at least $120,000 in annual income accounted for 32

percent of all the spending on home renovation in 2003, the latest year for

which data is available. That is up from 21 percent in 1995, adjusted for

inflation, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard. The

spending itself reached $233 billion in 2003, a rise of 52 percent from 1995.

For decades, a home in the suburbs was a family haven for the middle class, "a

kind of anchor in the heavy seas of urban life," as Kenneth T. Jackson, a

Columbia University historian, put it in his 1985 book "Crabgrass Frontier."

That was true of the owners of 150 Edgars Lane. But with the surge in home

prices, the big side yard took on a new dimension as a potentially valuable

building plot. It was no longer cherished as the colorful, terraced flower

garden nurtured by several former owners and written up admiringly in the local

newspaper.

The objections of neighbors stopped the owner of the house in 2001, a woman who

had received it in a divorce settlement, from obtaining a zoning variance so

that she could split off the old flower garden and sell the property as two lots

for more than the $819,000 that she finally received.

With that sale, the house moved out of the reach of middle-income buyers. The

buyer, Matthew Stover, came from Wall Street, and he soon sold the house to Mr.

Hirschfeld, also from Wall Street.

Still, the Stovers and the Hirschfelds, like nearly all of the owners before

them, came to Hastings from apartments in New York City, choosing the town in

part because it offered a demographic mix greater than many other suburbs, as

well as neighbors who were often artists, writers and academics.

The intellectual aura was particularly present on Edgars Lane. Margaret Sanger,

an early leader of the birth control movement, lived across the street from 150,

and Lewis Hine, the famous photographer of industrial realism, owned the house

two doors up. They are long gone, but the Hirschfelds, who received graduate

degrees from Oxford after going to college in the United States, are proud of

this legacy.

"We really wanted to live in Hastings," Mr. Hirschfeld said.

Suburban Diversity

The homes that made this town a suburb went up in the woody hills above

Broadway. Below that dividing street, blue-collar workers, many of them Polish

and Italian immigrants, occupied the apartments and row houses near the

waterfront, close to the chemical plant and the copper mill that employed them,

until the last factory closed in 1975.

The children of those workers went to school with the children in the hills and

"there is still a feeling that the diversity continues to exist - more a feeling

than a reality," David W. McCullough, a local historian, said.

As a community, Hastings tries to resist the trappings of affluence that are

spreading through so many suburbs. The downtown is still a collection of mostly

older stores and restaurants - reflecting "a certain pride that we have in the

shabbiness," as Mr. McCullough put it.

Very few of the upscale stores and restaurants evident elsewhere have arrived

here yet. But almost certainly they will as rising home prices, which limit

eligible newcomers to families like the Hirschfelds, gradually squeeze out

lower-income families.

The Hirschfelds, adding even greater value to their home, have installed air

conditioning, expanded the master bathroom and more than doubled the size of

Leila's bedroom, by constructing a second story on top of the kitchen wing. They

rebuilt the basement, spending far more than they intended to get rid of mold

and wetness, and took down the wall between the living room and the dining room,

creating what Mr. Hirschfeld described as "a flowing space so we can have a

conversation from the kitchen with someone who is two rooms away in the living

room." New windows are next.

"You can't live in this day and age with drafty windows," Mrs. Hirschfeld said.

"Either you pump your furnace for all it's worth all winter, or you have

double-glazed windows."

Drafty windows did not bother Ralph Breiling, who designed and built this house

in 1925 on land he had purchased three years earlier, spending less than $10,000

in all, or about $111,000 adjusted for inflation. Mr. Breiling was an architect,

but in the severe recession after World War I, he shifted to teaching school,

later rising to assistant principal and then principal of Brooklyn Technical

High School.

A group of teachers had purchased land in Hastings, and Mr. Breiling joined

them, buying one of the lots.

"He loved the Hudson Valley and when the leaves were off the trees, we had a

view of the river and the Palisades," Robert, one of his sons, remembered. For

years, "he commuted an hour and a half each way to his job."

When the Breiling family moved to Edgars Lane, the exterior was finished - it

looked then much as it looks today - but the interior walls were mostly

unfinished plaster. From then on, until he sold the house in 1950, Mr. Breiling

renovated, with his own hands.

A Love for the Hudson Valley

He built the one-car garage that is still there, and the room above it, which

became a children's playroom. He enclosed a patio, incorporating it into the

living room. When his third child, Clover, was born, he expanded a small sewing

room into the fourth bedroom, building out over the front door.

"He spread the work out; he could not afford to do it all at once," said Robert

Breiling, 83, now a retired engineer. "The Depression hit him hard. The New York

City schools cut pay in half. They said they would make it up after the war,

which they didn't. My mother started a nursery school in the dining room. She

had a bunch of little tables and chairs; made a schoolroom out of it. I thought

she liked doing it. But looking back it was for need."

The Breilings' lasting legacy was the garden in the big side yard, which Mr.

Breiling's wife, Leila, tended. In a 1933 article on "beautiful gardens of

Hastings," the weekly Hastings News had this to say about the Breilings' place:

"From the stone retaining wall along the street with its dense privet hedge up

to the children's terrace that now backs against the farm wall on the garden's

highest level, one passes, terrace by terrace, through grassy greensward,

flowering shrubs, long borders aglow with a hundred blossoms."

From that garden came the holly that Duncan Wilson fashioned into wreaths and

sold at Christmas. His parents, Byron and Jane Wilson, purchased 150 Edgars Lane

in 1951 for $25,000, the equivalent of a little less than $190,000 in today's

dollars, moving from a smaller home in nearby Dobbs Ferry when their third child

was still young.

"My mother decided that the family needed more space," Duncan Wilson, now 69,

recalls.

The Wilsons put energy into maintaining the elaborate garden, but they did

little to the house itself. They were square dancers, so they fixed up the

basement, refinishing the walls and tiling the floor, Mr. Duncan said. Like the

Breilings, they sold the house after their youngest child finished high school,

in 1963.

The next four owners either moved on quickly, to new jobs in other cities, or

stayed to raise children. The turnover helps to explain why the typical American

family owns a home for five or six years, a tenure unchanged going back decades.

Jerome and Carolyn Zinn stayed for eight years, having purchased the house in

1964 from a psychiatrist who lived in it only 18 months. The Zinns paid $40,000

- roughly $250,000 adjusted for inflation - coming from a city apartment with

eight-week-old twin boys.

"I knew that you raised children in a house," Mrs. Zinn said. "I didn't know

anything about Hastings or anyone in the community. We started out looking in

Yonkers and we wandered into Hastings and we liked the hilliness and the trees."

Mr. Zinn had started as a linotype operator, and his wife taught school, saving

enough from her salary for the $11,000 down payment. The remaining $29,000 was

the amount still owed on the psychiatrist's mortgage, which the Zinns took over

- a common practice in those days. Before coming to Hastings, Mr. Zinn had gone

from printer to owner of a small typography shop. It flourished, and in 1982 the

Zinns built a bigger home in Irvington, a neighboring town.

"I kept thinking I wanted to do this to the house and that to the house," Mrs.

Zinn said, "and then I said, if there are so many things I want to do we should

buy a house, or build one."

In 1974, the Zinns sold 150 Edgars Lane for $67,500 - adjusted for inflation,

not that much more than they had paid - to Gerald Franz, a specialist in

environmental issues then employed by the New York City Planning Commission, and

his wife, Susan, a public school math teacher. They had been married five years,

hoping to have children - they later adopted two daughters - and the purchase

price was a stretch for them.

"My expectation was to be married forever and to live there forever," Mrs. Franz

said.

What Was Once a Garden

The Zinns agreed to let the Franzes postpone payment for the side yard, and they

waited nearly a decade before they purchased that portion of their property for

$17,000. By then, with neither family caring for the garden, it had gone to seed

and Mr. Zinn, in any event, was thinking of its value as a building plot. "I had

always hoped in the back of my mind to get the variance to build," he said.

Divorce interrupted those plans. Mrs. Franz, who recently remarried and is now

Susan Franz Ledley, got the house in the 1996 settlement. By then, it was valued

at $500,000. As a school teacher, she could barely afford the upkeep and in

2001, while her youngest daughter was a high school senior, she sold it for

$819,000 - about $900,000 in today's dollars - to Mr. Stover, a stock analyst

for Citigroup, and his wife, Jeanine.

The Stovers were in their 30's and planning a family, like the Franzes nearly 30

years earlier. Unlike the Franzes, however, and all the other earlier owners,

they began to plan renovations, hiring an architect.

"Just as we were starting to get some steam, we were called to Boston," Mr.

Stover said. He took a better job in that city.