|

Vocapedia > Media > USA > NYT > Illustrations >

2008-2009

Wesley Bedrosian

Mind

When

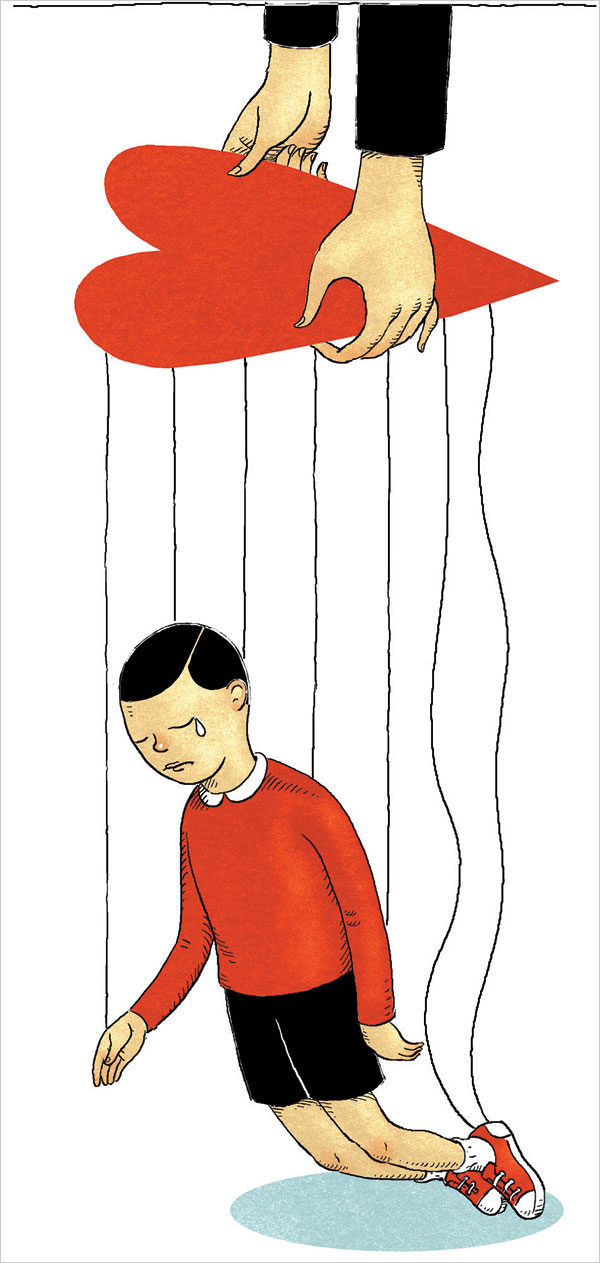

a Parent’s ‘I Love You’

Means ‘Do as I Say’

September 15, 2009

The New York Times

By ALFIE KOHN

More than 50 years ago, the psychologist Carl Rogers suggested

that simply loving our children wasn’t enough. We have to love them

unconditionally, he said — for who they are, not for what they do.

As a father, I know this is a tall order, but it becomes even more challenging

now that so much of the advice we are given amounts to exactly the opposite. In

effect, we’re given tips in conditional parenting, which comes in two flavors:

turn up the affection when they’re good, withhold affection when they’re not.

Thus, the talk show host Phil McGraw tells us in his book “Family First” (Free

Press, 2004) that what children need or enjoy should be offered contingently,

turned into rewards to be doled out or withheld so they “behave according to

your wishes.” And “one of the most powerful currencies for a child,” he adds,

“is the parents’ acceptance and approval.”

Likewise, Jo Frost of “Supernanny,” in her book of the same name (Hyperion,

2005), says, “The best rewards are attention, praise and love,” and these should

be held back “when the child behaves badly until she says she is sorry,” at

which point the love is turned back on.

Conditional parenting isn’t limited to old-school authoritarians. Some people

who wouldn’t dream of spanking choose instead to discipline their young children

by forcibly isolating them, a tactic we prefer to call “time out.” Conversely,

“positive reinforcement” teaches children that they are loved, and lovable, only

when they do whatever we decide is a “good job.”

This raises the intriguing possibility that the problem with praise isn’t that

it is done the wrong way — or handed out too easily, as social conservatives

insist. Rather, it might be just another method of control, analogous to

punishment. The primary message of all types of conditional parenting is that

children must earn a parent’s love. A steady diet of that, Rogers warned, and

children might eventually need a therapist to provide the unconditional

acceptance they didn’t get when it counted.

But was Rogers right? Before we toss out mainstream discipline, it would be nice

to have some evidence. And now we do.

In 2004, two Israeli researchers, Avi Assor and Guy Roth, joined Edward L. Deci,

a leading American expert on the psychology of motivation, in asking more than

100 college students whether the love they had received from their parents had

seemed to depend on whether they had succeeded in school, practiced hard for

sports, been considerate toward others or suppressed emotions like anger and

fear.

It turned out that children who received conditional approval were indeed

somewhat more likely to act as the parent wanted. But compliance came at a steep

price. First, these children tended to resent and dislike their parents. Second,

they were apt to say that the way they acted was often due more to a “strong

internal pressure” than to “a real sense of choice.” Moreover, their happiness

after succeeding at something was usually short-lived, and they often felt

guilty or ashamed.

In a companion study, Dr. Assor and his colleagues interviewed mothers of grown

children. With this generation, too, conditional parenting proved damaging.

Those mothers who, as children, sensed that they were loved only when they lived

up to their parents’ expectations now felt less worthy as adults. Yet despite

the negative effects, these mothers were more likely to use conditional

affection with their own children.

This July, the same researchers, now joined by two of Dr. Deci’s colleagues at

the University of Rochester, published two replications and extensions of the

2004 study. This time the subjects were ninth graders, and this time giving more

approval when children did what parents wanted was carefully distinguished from

giving less when they did not.

The studies found that both positive and negative conditional parenting were

harmful, but in slightly different ways. The positive kind sometimes succeeded

in getting children to work harder on academic tasks, but at the cost of

unhealthy feelings of “internal compulsion.” Negative conditional parenting

didn’t even work in the short run; it just increased the teenagers’ negative

feelings about their parents.

What these and other studies tell us, if we’re able to hear the news, is that

praising children for doing something right isn’t a meaningful alternative to

pulling back or punishing when they do something wrong. Both are examples of

conditional parenting, and both are counterproductive.

The child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, who readily acknowledged that the

version of negative conditional parenting known as time-out can cause “deep

feelings of anxiety,” nevertheless endorsed it for that very reason. “When our

words are not enough,” he said, “the threat of the withdrawal of our love and

affection is the only sound method to impress on him that he had better conform

to our request.”

But the data suggest that love withdrawal isn’t particularly effective at

getting compliance, much less at promoting moral development. Even if we did

succeed in making children obey us, though — say, by using positive

reinforcement — is obedience worth the possible long-term psychological harm?

Should parental love be used as a tool for controlling children?

Deeper issues also underlie a different sort of criticism. Albert Bandura, the

father of the branch of psychology known as social learning theory, declared

that unconditional love “would make children directionless and quite unlovable”

— an assertion entirely unsupported by empirical studies. The idea that children

accepted for who they are would lack direction or appeal is most informative for

what it tells us about the dark view of human nature held by those who issue

such warnings.

In practice, according to an impressive collection of data by Dr. Deci and

others, unconditional acceptance by parents as well as teachers should be

accompanied by “autonomy support”: explaining reasons for requests, maximizing

opportunities for the child to participate in making decisions, being

encouraging without manipulating, and actively imagining how things look from

the child’s point of view.

The last of these features is important with respect to unconditional parenting

itself. Most of us would protest that of course we love our children without any

strings attached. But what counts is how things look from the perspective of the

children — whether they feel just as loved when they mess up or fall short.

Rogers didn’t say so, but I’ll bet he would have been glad to see less demand

for skillful therapists if that meant more people were growing into adulthood

having already felt unconditionally accepted.

Alfie Kohn is the author of 11 books

about human behavior and

education,

including “Unconditional Parenting”

and “Punished by Rewards.”

When a Parent’s ‘I Love

You’ Means ‘Do as I Say’, NYT, 15.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/15/health/15mind.html

|