|

Vocapedia > Media > USA > NYT > Illustrations >

2008-2009

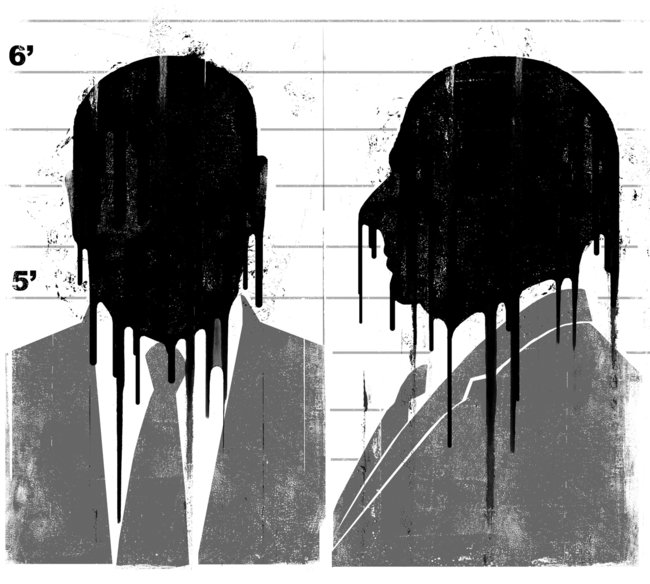

Edel Rodriguez

Prosecuting Crimes Against the Earth

June 3, 2010

The New York Times

By DAVID M. UHLMANN

Ann Arbor, Mich.

“IF our laws were broken ... we will bring those responsible to justice,”

President Obama pledged on Tuesday, in announcing an investigation of the events

leading to the April 20 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig. His

words may have been, in part, political damage control; efforts to contain the

spill remain dire. But federal prosecutors have been working behind the scenes

for weeks to determine whether BP, Transocean (the owner of the rig) and

Halliburton (the company that did the cementing job on the deep-ocean well)

should be charged with crimes.

Now, it’s up to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. to ensure that the legal

response to the calamitous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is better than the

emergency response.

If the spill had resulted from a hurricane or lightning strike, or if it had

been an unavoidable accident — an equipment failure that happened without

warning — it wouldn’t warrant criminal prosecution. Increasingly, however, it

appears that there was negligence or worse in the events leading to the

explosion of the rig.

News reports have described warning signs that went unheeded and deviations from

standard industry practice: Gas was seeping into the well. The blowout preventer

was leaking. Concerns were raised about the well casing. There were signs of

trouble with the cement in the well. Mud circulation was limited. A final

concrete plug was not properly installed. And when disaster struck, the blowout

preventer failed.

Prosecutors must examine all witness statements, internal documents and any

physical evidence that remains after the explosion. But if the news articles are

accurate, the Justice Department should bring criminal charges against BP, and

possibly Transocean and Halliburton, for violations of the Clean Water Act, the

Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Refuse Act — the same charges brought in the

Exxon Valdez case. Exxon ultimately paid a criminal fine of $125 million, the

largest ever for an environmental crime.

In this case, though, a fine of that size may not satisfy the many people who

are outraged by the gulf spill. The public expects felony charges and

multibillion-dollar fines.

All three of the environmental laws that may have been broken provide for

criminal penalties, but only the Clean Water Act includes felony charges. For

the government to prove a felony violation of the act it would need to

demonstrate that the defendant knew oil would be discharged into United States

waters. A felony violation can be easy to prove when a business dumps waste into

a river, but it’s harder in the case of an oil spill.

No one thinks BP, Transocean or Halliburton intended to spill oil into the gulf.

But given good evidence, the government could argue that the companies cut

corners or deviated so much from standard industry practice that they knew a

blowout could happen. Or, the government could argue that, even if the initial

gusher involved only negligence (a misdemeanor under the Clean Water Act) each

additional day represents a knowing violation. Both approaches are untested,

because there have been so few oil spill cases — but the gulf disaster warrants

trying aggressive strategies.

Ultimately, the public would like to see oil company executives brought up on

felony charges, leading to jail time that might inspire more careful drilling in

the future. But only those directly involved in misconduct can be charged with

crimes, and it is likely that executives of BP, Transocean and Halliburton

played no such personal role in the disaster.

Faced with these challenges, the Justice Department must find out whether BP or

the other companies misled the government about the integrity of the well, or

the amount of oil gushing from it. This could be the basis for charges of felony

obstruction of justice against the companies and individuals involved.

The Justice Department’s case against BP will be strengthened by the company’s

history of criminal violations, which offer evidence of a culture that puts

profits before the environment and worker safety. After a 2005 explosion at its

Texas City refinery, which killed 15 workers, BP pleaded guilty to violating the

Clean Air Act by failing to maintain a safe facility. It also pleaded guilty to

violating the Clean Water Act by having corroded pipelines that caused oil

spills in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay in 2006.

Criminal prosecution cannot restore the gulf or end the suffering of the people

who live along its shores. But it could ensure just punishment. And it would

make it more likely that the companies involved would pay all claims for damage

to the gulf coast, because the $75 million cap on liability, set by the Oil

Pollution Act of 1990, does not apply in criminal cases.

Most important, criminal prosecution would send a clear message that an

environmental disaster of this magnitude cannot be allowed to happen again.

David M. Uhlmann,

a law professor at the University of Michigan,

was the chief

of the environmental crimes section

at the United States Department of Justice

from 2000 to 2007.

Prosecuting Crimes

Against the Earth, NYT, 3.6.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/04/opinion/04uhlmann.html

Vocapedia > Media > USA > NYT > Illustrations >

2008-2009

|