|

Vocapedia >

Health >

Mental health >

Psychiatry

Psychiatrists, DSM

Dr. Darrel A. Regier

is co-chairman of a panel compiling the latest

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Photograph: Brendan Smialowski

for The New York Times

Psychiatrists Revising the Book

of Human Troubles

NYT

18 December 2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/18/

health/18psych.html

psychiatry UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/

psychiatry

psychiatry

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

mental-health-suicide-highmark-bcbs-insurance-denials - September 10, 2025

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/17/

health/laura-delano-psychiatric-meds.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/20/

health/los-angeles-homeless-psychiatry.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/21/

health/psychiatric-restraint-forced-medication.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/09/

health/psychedelics-mdma-psilocybin-molly-mental-health.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/01/27/

1227062470/keto-ketogenic-diet-mental-illness-bipolar-depression

https://www.npr.org/2019/11/18/

780563160/how-1-study-changed-the-field-of-psychiatry-forever

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/09/09/

746950433/telepsychiatry-helps-recruitment-and-patient-care-in-rural-areas

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/

716744558/how-psychiatry-turned-to-drugs-to-treat-mental-illness

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/09/

health/psychiatrist-holistic-mental-health.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/19/

opinion/psychiatrys-identity-crisis.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2013/05/16/

184454931/why-is-psychiatrys-new-manual-so-much-like-the-old-one

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/06/

the-limits-of-psychiatry/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/

health/21freedman.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/09/

opinion/l09psych.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/06/

health/policy/06doctors.html

forensic psychiatry UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jun/17/

inside-the-mind-of-murderer-

power-and-limits-of-forensic-psychiatry-crime-prison

telepsychiatry

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/09/09/

746950433/telepsychiatry-helps-recruitment-and-patient-care-

in-rural-areas

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2014/05/07/

308749287/telepsychiatry-brings-emergency-mental-health-care-

to-rural-areas/

American Psychiatric Association

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/21/

health/psychiatric-restraint-forced-medication.html

psychiatric hospitals

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

psychiatric-hospitals-emtala-mental-health-profit - September 23, 2025

antipsychiatry

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/

health/dr-thomas-szasz-psychiatrist-who-led-movement-against-his-field-

dies-at-92.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/sep/02/

rd-laing-mental-health-sanity

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/oct/04/

thomas-szasz

psychiatrist UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/12/

psychiatrists-under-fire-mental-health

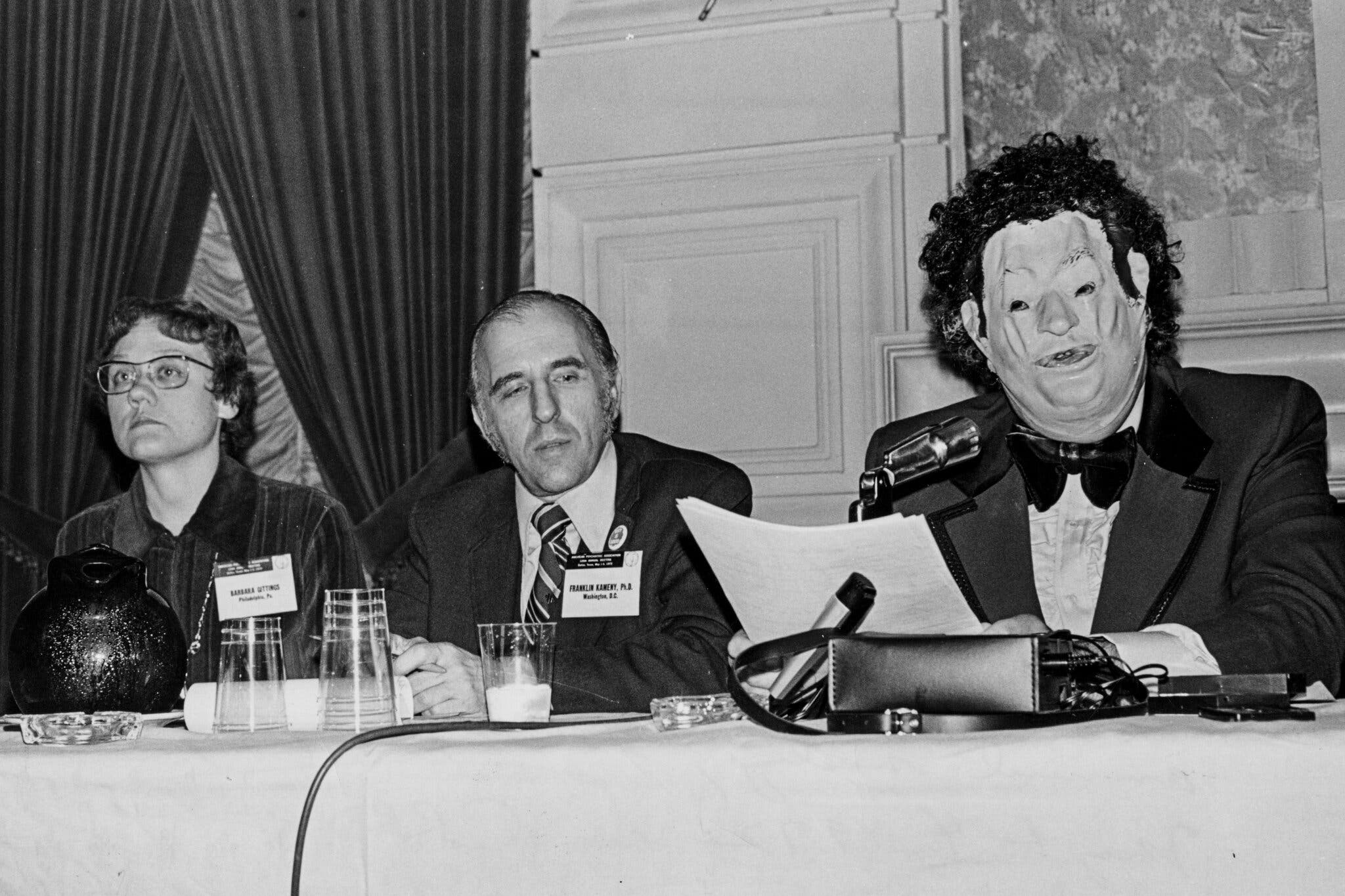

Dr. John Fryer,

a.k.a. “Dr. Henry Anonymous,” right,

during the 1972 convention

of the American Psychiatric

Association in Dallas.

Photograph: Kay Tobin,

via Manuscripts and Archives Division,

The New York Public

Library

He Spurred a Revolution in Psychiatry.

Then He ‘Disappeared.’

In 1972,

Dr. John Fryer risked his career to tell his colleagues

that gay people were not mentally ill.

His act sent ripples through the legal, medical

and justice

systems.

NYT

Published May 2, 2022

Updated May 6, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/02/

health/john-fryer-psychiatry.html

USA > psychiatrist

UK / USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

mental-health-suicide-highmark-bcbs-insurance-denials - September 10, 2025

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/18/

us/jeanne-hoff-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/02/

health/john-fryer-psychiatry.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/09/09/

746950433/telepsychiatry-helps-recruitment-and-patient-care-in-rural-areas

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/11/

well/live/chasing-my-shadow-as-a-cancer-patient-in-talk-therapy.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/30/

opinion/psychiatrists-trump.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/

opinion/psychiatrists-mass-killers.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/25/

539238529/goldwater-rule-still-in-place-

barring-many-psychiatrists-from-commenting-on-trum

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/26/

health/rural-nebraska-offers-stark-view-of-nursing-autonomy-debate.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/

opinion/sunday/great-betrayals.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2013/05/16/

184454931/why-is-psychiatrys-new-manual-so-much-like-the-old-one

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/oct/04/

thomas-szasz

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/05/us/

05greenspan.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/19/us/

19masterson.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/

health/23mind.html

Dr. Robert L. Spitzer

USA

considered by some

to be the father of modern psychiatry

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/19/

health/dr-robert-l-spitzer-noted-psychiatrist-apologizes-for-study-on-gay-cure.html

Charles Silverstein USA

1935-2023

psychologist and therapist

who played a key role in getting homosexuality

declassified as a mental illness,

https://www.npr.org/2023/02/09/

1155847480/charles-silverstein-psychologist-

declassify-homosexuality-mental-illness

Yehuda Nir USA 1930-2014

psychiatrist

whose childhood was

shaped

by having to masquerade

as a Roman

Catholic

in German-occupied Poland

to

escape Nazi persecution,

an ordeal that he turned

into a

well-received memoir

and that guided him

in treating

victims of trauma

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/

health/yehuda-nir-a-psychiatrist-and-holocaust-survivor-dies-at-84.html

psychiatrist USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/04/02/

1242170517/our-kids-are-not-ok-child-psychiatrist-harold-koplewicz-says

Thomas Szasz USA 1920-2012

psychiatrist

whose 1961 book

“The Myth of Mental Illness”

questioned the legitimacy of his field

and provided the intellectual grounding

for generations of critics,

patient advocates

and antipsychiatry activists,

making enemies of many fellow doctors

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/

health/dr-thomas-szasz-psychiatrist-who-led-movement-against-his-field-

dies-at-92.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/

health/dr-thomas-szasz-psychiatrist-who-led-movement-against-his-field-

dies-at-92.html

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/oct/04/

thomas-szasz

James Griffith Edwards USA 1928-2012

psychiatrist who helped establish

addiction medicine as a science,

formulating definitions

of drug and alcohol dependence

that are used worldwide

to diagnose and treat substance abuse

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/26/

health/dr-griffith-edwards-pioneer-in-addiction-medicine-dies-at-83.html

Thomas Szasz USA 1920-2012

psychiatrist

whose 1961 book

“The Myth of Mental Illness”

questioned the legitimacy of his field

and provided the intellectual grounding

for generations of critics,

patient advocates

and antipsychiatry activists,

making enemies of many fellow doctors

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/

health/dr-thomas-szasz-psychiatrist-who-led-movement-against-his-field-

dies-at-92.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/

health/dr-thomas-szasz-psychiatrist-who-led-movement-against-his-field-

dies-at-92.html

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/oct/04/

thomas-szasz

John Ercel Fryer USA

1937-2003

In 1972,

Dr. John Fryer risked his career

to tell his colleagues

that gay people were not mentally ill.

His act sent ripples

through the legal, medical and justice systems.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/02/

health/john-fryer-psychiatry.html

mental disorders / mental health

disorders

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/24/us/

debate-persists-over-diagnosing-mental-health-disorders-long-after-sybil.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/01/health/

study-finds-genetic-risk-factors-shared-by-5-psychiatric-disorders.html

borderline personality disorder

USA

personality disorder

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/19/us/19masterson.html

mental disorders on campus

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/01/12/

dealing-with-mental-disorders-on-campus

eating disorders

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/14/

business/ruling-offers-hope-to-eating-disorder-sufferers.html

eating disorders > Anorexia

Nervosa

eating disorders > Bulimia

narcissism

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/19/us/

19masterson.html

narcissistic personality disorder

lack

empathy UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/12/

donald-trump-king-narcissist-victory

lack of empathy

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/14/

opinion/an-eminent-psychiatrist-demurs-on-trumps-mental-state.html

psychosis

UK

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/

features/living-with-psychosis-im-mad-but-not-bad-2025012.html

hypochondria

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/13/

opinion/sunday/hypochondria-an-inside-look.html

psychiatric

medication

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/17/

health/laura-delano-psychiatric-meds.html

medication

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/30/

opinion/psychotherapys-image-problem.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/26/

opinion/sunday/sunday-dialogue-treating-mental-illness.html

meds USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/

opinion/coronavirus-anxiety-medication.html

FRONTLINE > The Medicated Child

Aired: 01/08/2008 56:10 Rating: NR

Millions of U.S. children are taking psychiatric drugs,

most never tested on

kids.

Good medicine - or an uncontrolled experiment?

https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-the-medicated-child/

psychiatric disorders

USA > Diagnostic

and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders DSM

UK / USA

https://www.psychiatry.org/

psychiatrists/practice/dsm

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/feb/25/

this-feels-more-like-spin-the-bottle-than-science-

my-mission-to-find-a-proper-diagnosis-and-treatment-for-my-sons-psychosis

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/14/

opinion/an-eminent-psychiatrist-demurs-on-trumps-mental-state.html

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/30/

diagnosed-donald-trump-goldwater-rule-mental-health

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/aug/04/truly-madly-deeply-delusional

http://www.npr.org/2013/05/31/

187534467/bad-diagnosis-for-new-psychiatry-bible

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/28/

opinion/brooks-heroes-of-uncertainty.html

https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2013/may/28/

politics-psychiatry

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2013/05/16/

184454931/why-is-psychiatrys-new-manual-so-much-like-the-old-one

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2013/may/12/psychiatrists-under-fire-mental-health

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/

health/psychiatrys-new-guide-falls-short-experts-say.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/12/

opinion/break-up-the-psychiatric-monopoly.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/09/

health/dsm-panel-backs-down-on-diagnoses.html

http://www.npr.org/2012/12/04/1

66503627/the-challenges-posed-by-personality-disorders

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/18/health/18psych.html

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/

story.php?storyId=1400925 - 18 August 2003

psychiatric name-calling USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/14/

opinion/an-eminent-psychiatrist-demurs-on-trumps-mental-state.html

recovery

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/25/

health/mental-health-depression-recovery.html

Corpus of news articles

Health > Mental health > Therapists

Psychologists, Psychoanalysts,

Psychiatrists, DSM, Therapy

Maurice

M. Rapport,

Who Studied Serotonin,

Dies at 91

September

2, 2011

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GRIMES

Maurice M.

Rapport, a biochemist who helped isolate and name the neurotransmitter

serotonin, which plays a role in regulating mood and mental states, and who

first described its molecular structure, a development that led to the creation

of a wide variety of psychiatric and other drugs, died on Aug. 18 in Durham,

N.C. He was 91.

The death was confirmed by his daughter, Erica Rapport Gringle.

In the 1940s Dr. Rapport (pronounced RA-port) was a freshly minted biochemist

from the California Institute of Technology when he began working at the

Cleveland Clinic Foundation with Irvine H. Page, a leading specialist on high

blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.

Scientists had known since the 1860s of a substance in the serum released during

clotting that constricts blood vessels by acting on the smooth muscles of the

blood-vessel walls. In the 20th century, researchers pinpointed its source in

blood platelets, but its identity remained a mystery.

Dr. Rapport, working with Dr. Page and Arda A. Green, isolated the substance

and, in a paper published in 1948, gave it a name: serotonin, derived from

“serum” and “tonic.”

On his own, Dr. Rapport identified the structure of serotonin as

5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT, as it is called by pharmacologists. His findings,

published in 1949, made it possible for commercial laboratories to synthesize

serotonin and study its properties as a neurotransmitter.

More than 90,000 scientific papers have been published on 5-HT, and the

Serotonin Club, a professional organization, regularly holds conferences to

report on research in the field.

Initially, researchers focused on agents to block serotonin, which, by

constricting blood vessels, causes blood pressure to rise. After researchers

discovered its presence in the brain, and its chemical similarity to LSD, which

mimics serotonin in the brain, they began focusing on serotonin’s role in

regulating mood and mental functioning.

Further research showed that serotonin also plays a critical role in the central

nervous system — where it helps regulate mood, appetite, sex and sleep — and the

gut.

This new understanding of the structure and functioning of serotonin led to a

changing view of mental disorders as chemical imbalances and opened the way to

the development of antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs that act on 5-HT, as

well as drugs for treating cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease.

Maurice Rapoport was born on Sept. 23, 1919, in Atlantic City. His father, a

furrier who had emigrated from Russia, left the family when Maurice was a small

child. His mother changed the spelling of the family name and Maurice later

adopted the middle initial “M,” although it did not stand for anything.

After graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, he earned a

bachelor’s degree in chemistry from City College in 1940 and a doctorate in

organic chemistry from Cal Tech in 1946. For his work on serotonin he was

awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 1952 to study with Dr. Daniel Bovet, later a

Nobel Prize winner for his work in pharmacology, at the Istituto Superiore di

Sanità in Rome.

After doing research in biochemistry at Columbia, immunology at the

Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research and biochemistry at the Albert

Einstein College of Medicine, Dr. Rapport joined the staff of the New York

Psychiatric Institute, where he created the division of neuroscience by

combining the old divisions of chemistry, pharmacology and bacteriology. He also

held the post of professor of biochemistry at Columbia’s College of Physicians

and Surgeons.

Dr. Rapport retired in 1986 and was a visiting professor in the neurology

department of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine until his death.

Dr. Rapport did important research on cancer, cardiovascular disease,

connective-tissue disease and demyelinating diseases, a type of nervous-system

disorder that includes multiple sclerosis.

One productive area of his research focused on the immunological activity of

lipids found in the nervous system, notably cytolipin H, which he isolated from

human cancer tissue in 1958. He also identified the lipid galactocerebroside as

the substance responsible for producing antigens specific to the brain, a

finding that led to a better understanding of the immune system.

Dr. Rapport’s wife, Edith, died in 1988. He lived in Hastings-on-Hudson with his

longtime companion, Nancy Reich, who survives him, before failing health made it

necessary for him to move in with his daughter, Erica, in Durham, in July. Other

survivors are his son, Ezra, of Oakland, Calif.; five grandchildren; and a

great-granddaughter.

Maurice M. Rapport, Who Studied Serotonin, Dies at 91,

NYT, 2.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/03/health/03rapport.html

Alfred

Freedman,

a Leader in Psychiatry,

Dies at 94

April 20,

2011

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GRIMES

Dr. Alfred

M. Freedman, a psychiatrist and social reformer who led the American Psychiatric

Association in 1973 when, overturning a century-old policy, it declared that

homosexuality was not a mental illness, died on Sunday in Manhattan. He was 94.

The cause was complications of surgery to treat a fractured hip, his son Dan

said.

In 1972, with pressure mounting from gay rights groups and from an increasing

number of psychiatrists to destigmatize homosexuality, Dr. Freedman was elected

president of the association, which he later described as a conservative “old

boys’ club.” Its 20,000 members were deeply divided about its policy on

homosexuality, which its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

II classified as a “sexual deviation” in the same class as fetishism, voyeurism,

pedophilia and exhibitionism.

Well known as the chairman of the department of psychiatry at New York Medical

College and a strong proponent of community-oriented psychiatric and social

services, Dr. Freedman was approached by a group of young reformers, the

Committee of Concerned Psychiatrists, who persuaded him to run as a petition

candidate for the presidency of the psychiatric association.

Dr. Freedman, much to his surprise, won what may have been the first contested

election in the organization’s history — by 3 votes out of more than 9,000 cast.

Immediately on taking office, he threw his support behind a resolution, drafted

by Robert L. Spitzer of Columbia University, to remove homosexuality from the

list of mental disorders.

On Dec. 15, 1973, the board of trustees, many of them newly elected younger

psychiatrists, voted 13 to 0, with two abstentions, in favor of the resolution,

which stated that “by itself, homosexuality does not meet the criteria for being

a psychiatric disorder.”

It went on: “We will no longer insist on a label of sickness for individuals who

insist that they are well and demonstrate no generalized impairment in social

effectiveness.”

The board stopped short of declaring homosexuality “a normal variant of human

sexuality,” as the association’s task force on nomenclature had recommended.

The recently formed National Gay Task Force (now the National Gay and Lesbian

Task Force) hailed the resolution as “the greatest gay victory,” one that

removed “the cornerstone of oppression for one-tenth of our population.” Among

other things, the resolution helped reassure gay men and women in need of

treatment for mental problems that doctors would not have any authorization to

try to change their sexual orientation, or to identify homosexuality as the root

cause of their difficulties.

An equally important companion resolution condemned discrimination against gays

in such areas as housing and employment. In addition, it called on local, state

and federal lawmakers to pass legislation guaranteeing gay citizens the same

protections as other Americans, and to repeal all criminal statutes penalizing

sex between consenting adults.

The resolution served as a model for professional and religious organizations

that took similar positions in the years to come.

“It was a huge victory for a movement that in 1973 was young, small, very

underfunded and had not yet had this kind of political validation,” said Sue

Hyde, who organizes the annual conference of the National Gay and Lesbian Task

Force. “It is the single most important event in the history of what would

become the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender movement.”

In a 2007 interview Dr. Freedman said, “I felt at the time that that decision

was the most important thing we accomplished.”

Alfred Mordecai Freedman was born on Jan. 7, 1917, in Albany. He won

scholarships to study at Cornell, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1937.

He earned a medical degree from the University of Minnesota in 1941 but cut

short his internship at Harlem Hospital to enlist in the Army Air Corps.

During World War II he served as a laboratory officer in Miami and chief of

laboratories at the Air Corps hospital in Gulfport, Miss. He left the corps with

the rank of major.

After doing research on neuropsychology with Harold E. Himwich at Edgewood

Arsenal in Maryland, he became interested in the development of human cognition.

He underwent training in general and child psychiatry and began a residency at

Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, where he became a senior child psychiatrist.

He was the chief psychiatrist in the pediatrics department at the Downstate

College of Medicine of the State University of New York for five years before

becoming the first full-time chairman of the department of psychiatry at New

York Medical College, then in East Harlem and now in Valhalla, N.Y.

In his 30 years at the college he built the department into an important

teaching institution with a large residency program. He greatly expanded the

psychiatric services offered at nearby Metropolitan Hospital, which is

affiliated with the school and where he was director of psychiatry.

To address social problems in East Harlem, Dr. Freedman created a treatment

program for adult drug addicts at the hospital in 1959 and the next year

established a similar program for adolescents. These were among the earliest

drug addiction programs to be conducted by a medical school and to be based in a

general hospital. He also founded a division of social and community psychiatry

at the school to serve neighborhood residents.

With Harold I. Kaplan, he edited “Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry,” which

became adopted as a standard text on its publication in 1967 and is now in its

ninth edition.

During his one-year term as president of the American Psychiatric Association,

Dr. Freedman made the misuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union one of the

organization’s main issues. He challenged the Soviet government to answer

charges that it routinely held political dissidents in psychiatric hospitals,

and he led a delegation of American psychiatrists to the Soviet Union to visit

mental hospitals and confer with Soviet psychiatrists.

After retiring from New York Medical College, Dr. Freedman turned his attention

to the role that psychiatry played in death penalty cases. With his colleague

Abraham L. Halpern, he lobbied the American Medical Association to enforce the

provision in its code of ethics barring physicians from taking part in

executions, and he campaigned against the practice of using psychopharmacologic

drugs on psychotic death-row prisoners so that they could be declared competent

to be executed.

In addition to his son Dan, of Silver Spring, Md., he is survived by his wife,

Marcia; another son, Paul, of Pelham, N.Y.; and three grandchildren.

Alfred Freedman, a Leader in Psychiatry, Dies at 94, NYT,

20.4.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/health/21freedman.html

Talk Doesn’t Pay,

So Psychiatry Turns

to Drug Therapy

March 5, 2011

The New York Times

By GARDINER HARRIS

DOYLESTOWN, Pa. — Alone with his psychiatrist, the patient confided that his

newborn had serious health problems, his distraught wife was screaming at him

and he had started drinking again. With his life and second marriage falling

apart, the man said he needed help.

But the psychiatrist, Dr. Donald Levin, stopped him and said: “Hold it. I’m not

your therapist. I could adjust your medications, but I don’t think that’s

appropriate.”

Like many of the nation’s 48,000 psychiatrists, Dr. Levin, in large part because

of changes in how much insurance will pay, no longer provides talk therapy, the

form of psychiatry popularized by Sigmund Freud that dominated the profession

for decades. Instead, he prescribes medication, usually after a brief

consultation with each patient. So Dr. Levin sent the man away with a referral

to a less costly therapist and a personal crisis unexplored and unresolved.

Medicine is rapidly changing in the United States from a cottage industry to one

dominated by large hospital groups and corporations, but the new efficiencies

can be accompanied by a telling loss of intimacy between doctors and patients.

And no specialty has suffered this loss more profoundly than psychiatry.

Trained as a traditional psychiatrist at Michael Reese Hospital, a sprawling

Chicago medical center that has since closed, Dr. Levin, 68, first established a

private practice in 1972, when talk therapy was in its heyday.

Then, like many psychiatrists, he treated 50 to 60 patients in once- or

twice-weekly talk-therapy sessions of 45 minutes each. Now, like many of his

peers, he treats 1,200 people in mostly 15-minute visits for prescription

adjustments that are sometimes months apart. Then, he knew his patients’ inner

lives better than he knew his wife’s; now, he often cannot remember their names.

Then, his goal was to help his patients become happy and fulfilled; now, it is

just to keep them functional.

Dr. Levin has found the transition difficult. He now resists helping patients to

manage their lives better. “I had to train myself not to get too interested in

their problems,” he said, “and not to get sidetracked trying to be a

semi-therapist.”

Brief consultations have become common in psychiatry, said Dr. Steven S.

Sharfstein, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association and the

president and chief executive of Sheppard Pratt Health System, Maryland’s

largest behavioral health system.

“It’s a practice that’s very reminiscent of primary care,” Dr. Sharfstein said.

“They check up on people; they pull out the prescription pad; they order tests.”

With thinning hair, a gray beard and rimless glasses, Dr. Levin looks every bit

the psychiatrist pictured for decades in New Yorker cartoons. His office, just

above Dog Daze Canine Hair Designs in this suburb of Philadelphia, has matching

leather chairs, and African masks and a moose head on the wall. But there is no

couch or daybed; Dr. Levin has neither the time nor the space for patients to

lie down anymore.

On a recent day, a 50-year-old man visited Dr. Levin to get his prescriptions

renewed, an encounter that took about 12 minutes.

Two years ago, the man developed rheumatoid arthritis and became severely

depressed. His family doctor prescribed an antidepressant, to no effect. He went

on medical leave from his job at an insurance company, withdrew to his basement

and rarely ventured out.

“I became like a bear hibernating,” he said.

Missing the Intrigue

He looked for a psychiatrist who would provide talk therapy, write prescriptions

if needed and accept his insurance. He found none. He settled on Dr. Levin, who

persuaded him to get talk therapy from a psychologist and spent months adjusting

a mix of medications that now includes different antidepressants and an

antipsychotic. The man eventually returned to work and now goes out to movies

and friends’ houses.

The man’s recovery has been gratifying for Dr. Levin, but the brevity of his

appointments — like those of all of his patients — leaves him unfulfilled.

“I miss the mystery and intrigue of psychotherapy,” he said. “Now I feel like a

good Volkswagen mechanic.”

“I’m good at it,” Dr. Levin went on, “but there’s not a lot to master in

medications. It’s like ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ where you had Hal the

supercomputer juxtaposed with the ape with the bone. I feel like I’m the ape

with the bone now.”

The switch from talk therapy to medications has swept psychiatric practices and

hospitals, leaving many older psychiatrists feeling unhappy and inadequate. A

2005 government survey found that just 11 percent of psychiatrists provided talk

therapy to all patients, a share that had been falling for years and has most

likely fallen more since. Psychiatric hospitals that once offered patients

months of talk therapy now discharge them within days with only pills.

Recent studies suggest that talk therapy may be as good as or better than drugs

in the treatment of depression, but fewer than half of depressed patients now

get such therapy compared with the vast majority 20 years ago. Insurance company

reimbursement rates and policies that discourage talk therapy are part of the

reason. A psychiatrist can earn $150 for three 15-minute medication visits

compared with $90 for a 45-minute talk therapy session.

Competition from psychologists and social workers — who unlike psychiatrists do

not attend medical school, so they can often afford to charge less — is the

reason that talk therapy is priced at a lower rate. There is no evidence that

psychiatrists provide higher quality talk therapy than psychologists or social

workers.

Of course, there are thousands of psychiatrists who still offer talk therapy to

all their patients, but they care mostly for the worried wealthy who pay in

cash. In New York City, for instance, a select group of psychiatrists charge

$600 or more per hour to treat investment bankers, and top child psychiatrists

charge $2,000 and more for initial evaluations.

When he started in psychiatry, Dr. Levin kept his own schedule in a spiral

notebook and paid college students to spend four hours a month sending out

bills. But in 1985, he started a series of jobs in hospitals and did not return

to full-time private practice until 2000, when he and more than a dozen other

psychiatrists with whom he had worked were shocked to learn that insurers would

no longer pay what they had planned to charge for talk therapy.

“At first, all of us held steadfast, saying we spent years learning the craft of

psychotherapy and weren’t relinquishing it because of parsimonious policies by

managed care,” Dr. Levin said. “But one by one, we accepted that that craft was

no longer economically viable. Most of us had kids in college. And to have your

income reduced that dramatically was a shock to all of us. It took me at least

five years to emotionally accept that I was never going back to doing what I did

before and what I loved.”

He could have accepted less money and could have provided time to patients even

when insurers did not pay, but, he said, “I want to retire with the lifestyle

that my wife and I have been living for the last 40 years.”

“Nobody wants to go backwards, moneywise, in their career,” he said. “Would

you?”

Dr. Levin would not reveal his income. In 2009, the median annual compensation

for psychiatrists was about $191,000, according to surveys by a medical trade

group. To maintain their incomes, physicians often respond to fee cuts by

increasing the volume of services they provide, but psychiatrists rarely earn

enough to compensate for their additional training. Most would have been better

off financially choosing other medical specialties.

Dr. Louisa Lance, a former colleague of Dr. Levin’s, practices the old style of

psychiatry from an office next to her house, 14 miles from Dr. Levin’s office.

She sees new patients for 90 minutes and schedules follow-up appointments for 45

minutes. Everyone gets talk therapy. Cutting ties with insurers was frightening

since it meant relying solely on word-of-mouth, rather than referrals within

insurers’ networks, Dr. Lance said, but she cannot imagine seeing patients for

just 15 minutes. She charges $200 for most appointments and treats fewer

patients in a week than Dr. Levin treats in a day.

“Medication is important,” she said, “but it’s the relationship that gets people

better.”

Dr. Levin’s initial efforts to get insurers to reimburse him and persuade his

clients to make their co-payments were less than successful. His office

assistants were so sympathetic to his tearful patients that they often failed to

collect. So in 2004, he begged his wife, Laura Levin — a licensed talk therapist

herself, as a social worker — to take over the business end of the practice.

Ms. Levin created accounting systems, bought two powerful computers, licensed a

computer scheduling program from a nearby hospital and hired independent

contractors to haggle with insurers and call patients to remind them of

appointments. She imposed a variety of fees on patients: $50 for a missed

appointment, $25 for a faxed prescription refill and $10 extra for a missed

co-payment.

As soon as a patient arrives, Ms. Levin asks firmly for a co-payment, which can

be as much as $50. She schedules follow-up appointments without asking for

preferred times or dates because she does not want to spend precious minutes as

patients search their calendars. If patients say they cannot make the

appointments she scheduled, Ms. Levin changes them.

“This is about volume,” she said, “and if we spend two minutes extra or five

minutes extra with every one of 40 patients a day, that means we’re here two

hours longer every day. And we just can’t do it.”

She said that she would like to be more giving of herself, particularly to

patients who are clearly troubled. But she has disciplined herself to confine

her interactions to the business at hand. “The reality is that I’m not the

therapist anymore,” she said, words that echoed her husband’s.

Drawing the Line

Ms. Levin, 63, maintains a lengthy waiting list, and many of the requests are

heartbreaking. On a January day, a pregnant mother of a 3-year-old called to say

that her husband was so depressed he could not rouse himself from bed. Could he

have an immediate appointment? Dr. Levin’s first opening was a month away.

“I get a call like that every day, and I find it really distressing,” Ms. Levin

said. “But do we work 12 hours every day instead of 11? At some point, you have

to make a choice.”

Initial consultations are 45 minutes, while second and later visits are 15. In

those first 45 minutes, Dr. Levin takes extensive medical, psychiatric and

family histories. He was trained to allow patients to tell their stories in

their own unhurried way with few interruptions, but now he asks a rapid-fire

series of questions in something akin to a directed interview. Even so, patients

sometimes fail to tell him their most important symptoms until the end of the

allotted time.

“There was a guy who came in today, a 56-year-old man with a series of business

failures who thinks he has A.D.D.,” or attention deficit disorder, Dr. Levin

said. “So I go through the whole thing and ask a series of questions about

A.D.D., and it’s not until the very end when he says, ‘On Oct. 28, I thought

life was so bad, I was thinking about killing myself.’ ”

With that, Dr. Levin began to consider an entirely different diagnosis from the

man’s pattern of symptoms: excessive worry, irritability, difficulty falling

asleep, muscle tension in his back and shoulders, persistent financial woes, the

early death of his father, the disorganization of his mother.

“The thread that runs throughout this guy’s life is anxiety, not A.D.D. —

although anxiety can impair concentration,” said Dr. Levin, who prescribed an

antidepressant that he hoped would moderate the man’s anxiety. And he pressed

the patient to see a therapist, advice patients frequently ignore. The visit

took 55 minutes, putting Dr. Levin behind schedule.

In 15-minute consultations, Dr. Levin asks for quick updates on sleep, mood,

energy, concentration, appetite, irritability and problems like sexual

dysfunction that can result from psychotropic medications.

“And people want to tell me about what’s going on in their lives as far as

stress,” Dr. Levin said, “and I’m forced to keep saying: ‘I’m not your

therapist. I’m not here to help you figure out how to get along with your boss,

what you do that’s self-defeating, and what alternative choices you have.’ ”

Dr. Levin, wearing no-iron khakis, a button-down blue shirt with no tie, blue

blazer and loafers, had a cheery greeting for his morning patients before

ushering them into his office. Emerging 15 minutes later after each session, he

would walk into Ms. Levin’s adjoining office to pick up the next chart, announce

the name of the patient in the waiting room and usher that person into his

office.

He paused at noon to spend 15 minutes eating an Asian chicken salad with Ramen

noodles. He got halfway through the salad when an urgent call from a patient

made him put down his fork, one of about 20 such calls he gets every day.

By afternoon, he had dispensed with the cheery greetings. At 6 p.m., his waiting

room empty, Dr. Levin heaved a sigh after emerging from his office with his 39th

patient. Then the bell on his entry door tinkled again, and another patient came

up the stairs.

“Oh, I thought I was done,” Dr. Levin said, disappointed. Ms. Levin handed him

the last patient’s chart.

Quick Decisions

The Levins said they did not know how long they could work 11-hour days. “And if

the stock market hadn’t gone down two years ago, we probably wouldn’t be working

this hard now,” Ms. Levin said.

Dr. Levin said that the quality of treatment he offers was poorer than when he

was younger. For instance, he was trained to adopt an unhurried analytic calm

during treatment sessions. “But my office is like a bus station now,” he said.

“How can I have an analytic calm?”

And years ago, he often saw patients 10 or more times before arriving at a

diagnosis. Now, he makes that decision in the first 45-minute visit. “You have

to have a diagnosis to get paid,” he said with a shrug. “I play the game.”

In interviews, six of Dr. Levin’s patients — their identities, like those of the

other patients, are being withheld to protect their privacy — said they liked

him despite the brief visits. “I don’t need a half-hour or an hour to talk,”

said a stone mason who has panic attacks and depression and is prescribed an

antidepressant. “Just give me some medication, and that’s it. I’m O.K.”

Another patient, a licensed therapist who has post-partum depression worsened by

several miscarriages, said she sees Dr. Levin every four weeks, which is as

often as her insurer will pay for the visits. Dr. Levin has prescribed

antidepressants as well as drugs to combat anxiety. She also sees a therapist,

“and it’s really, really been helping me, especially with my anxiety,” she said.

She said she likes Dr. Levin and feels that he listens to her.

Dr. Levin expressed some astonishment that his patients admire him as much as

they do.

“The sad thing is that I’m very important to them, but I barely know them,” he

said. “I feel shame about that, but that’s probably because I was trained in a

different era.”

The Levins’s youngest son, Matthew, is now training to be a psychiatrist, and

Dr. Donald Levin said he hoped that his son would not feel his ambivalence about

their profession since he will not have experienced an era when psychiatrists

lavished time on every patient. Before the 1920s, many psychiatrists were stuck

in asylums treating confined patients covered in filth, so most of the 20th

century was unusually good for the profession.

In a telephone interview from the University of California, Irvine, where he is

completing the last of his training to become a child and adolescent

psychiatrist, Dr. Matthew Levin said, “I’m concerned that I may be put in a

position where I’d be forced to sacrifice patient care to make a living, and I’m

hoping to avoid that.”

Talk Doesn’t Pay, So

Psychiatry Turns to Drug Therapy, NYT, 5.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/06/health/policy/06doctors.html

Getting Someone

to Psychiatric Treatment

Can Be Difficult

and

Inconclusive

January 18, 2011

The New York Times

By A. G. SULZBERGER

and BENEDICT CAREY

TUCSON —What are you supposed to do with someone like Jared L. Loughner?

That question is as difficult to answer today as it was in the years and months

and days leading up to the shooting here that left 6 dead and 13 wounded.

Millions of Americans have wondered about a troubled loved one, friend or

co-worker, fearing not so much an act of violence, but — far more likely —

self-inflicted harm, landing in the streets, in jail or on suicide watch. But

those in a position to help often struggle with how to distinguish ominous

behavior from the merely odd, the red flags from the red herrings.

In Mr. Loughner’s case there is no evidence that he ever received a formal

diagnosis of mental illness, let alone treatment. Yet many psychiatrists say

that the warning sings of a descent into psychosis were there for months, and

perhaps far longer.

Moving a person who is resistant into treatment is an emotional, sometimes

exhausting process that in the end may not lead to real changes in behavior.

Mental health resources are scarce in most states, laws make it difficult to

commit an adult involuntarily, and even after receiving treatment, patients

frequently stop taking their medication or seeing a therapist, believing that

they are no longer ill.

The Virginia Tech gunman was committed involuntarily before killing 32 people in

a 2007 rampage.

With Mr. Loughner, dozens of people apparently saw warning signs: the classmates

who listened as his dogmatic language grew more detached from reality. The

police officers who nervously advised that he could not return to college

without a medical note stating that he was not dangerous. His father, who chased

him into the desert hours before the attack as Mr. Loughner carried a black bag

full of ammunition.

“This isn’t an isolated incident,” said Daniel J. Ranieri, president of La

Frontera Center, a nonprofit group that provides mental health services. “There

are lots of people who are operating on the fringes who I would describe as

pretty combustible. And most of them aren’t known to the mental health system.”

Dr. Jack McClellan, an adult and child psychiatrist at the University of

Washington, said he advises people who are worried that someone is struggling

with a mental disorder to watch for three things — a sudden change in

personality, in thought processes, or in daily living. “This is not about

whether someone is acting bizarrely; many people, especially young people,

experiment with all sorts of strange beliefs and counterculture ideas,” Dr.

McLellan said. “We’re talking about a real change. Is this the same person you

knew three months ago?”

Those who have watched the mental unraveling of a loved one say that recognizing

the signs is only the first step in an emotional, often confusing, process.

About half of people with mental illnesses do not receive treatment, experts

estimate, in part because many of them do not recognize that they even have an

illness.

Pushing such a person into treatment is legally difficult in most states,

especially when he or she is an adult — and the attempt itself can shatter the

trust between a troubled soul and the one who is most desperate to help. Others,

though, later express gratitude.

“If the reason is love, don’t worry if they’ll be mad at you,” said Robbie

Alvarez, 28, who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia after being involuntarily

committed when his increasingly erratic behavior led to a suicide attempt. At

the time, he said, he was living in Phoenix with his parents, who he was

convinced were trying to kill him. In Arizona it is easier to obtain an

involuntary commitment than in many states because anyone can request an

evaluation if they observe behavior that suggests a person may present a danger

or is severely disabled (often state laws require some evidence of imminent

danger to self or others).

But there are also questions about whether the system can accommodate an influx

of new patients. Arizona’s mental health system has been badly strained by

recent budget cuts that left those without Medicaid stripped of most of their

services, including counseling and residential treatment, though eligibility

remains for emergency services like involuntary commitment. And the state is

trying to change eligibility requirements for Medicaid, which would potentially

reduce financing further and leave more with limited services.

Still, people who have been through the experience argue that it is better to

act sooner rather than later. “It’s not easy to know when we could or should

intervene but I would rather err on the side of safety than not,” said H. Clarke

Romans, executive director of the local chapter of the National Alliance on

Mental Illness, an advocacy group, who had a son with schizophrenia.

The collective failure to move Mr. Loughner into treatment, either voluntarily

or not, will never be fully understood, because those who knew the young man

presumably wrestled separately and privately about whether to take action. But

the inaction has certainly provoked second-guessing. Sheriff Clarence Dupnik of

Pima County told CNN last Wednesday that Mr. Loughner’s parents were as shocked

as everyone else. “It’s been very, very devastating for them,” he said. “They

had absolutely no way to predict this kind of behavior.”

Linda Rosenberg, president of the National Council for Community Behavioral

Healthcare, said, “The failure here is that we ignored someone for a long time

who was clearly in tremendous distress.” Ms. Rosenberg, whose group is a

nonprofit agency leading a campaign to teach people how to recognize and respond

to signs of mental illness, added, “He wasn’t someone who could ask for help

because his thinking was affected, and as a community no one said, let’s stop

and make sure he gets help.”

At the University of Arizona, where a nursing student killed three instructors

on campus eight years ago before killing himself, feelings of sadness and anger

initially mixed with some guilt as the university examined the missed warning

signs.

The overhauled process for addressing concerns is now more responsive, even if

there are sometimes false alarms, said Melissa M. Vito, vice president for

student affairs. “I guess I’d rather explain why I called someone’s parents than

why I didn’t do something,” she said.

Many others feel the same way.

Four years ago Susan Junck watched her 18-year-old son return from community

college to their Phoenix home one afternoon and, after preparing a snack,

repeatedly call the police to accuse his mother of poisoning him. She assumed it

was an isolated outburst, maybe connected to his marijuana use. In the coming

months, though, her son’s behavior grew more alarming, culminating in an arrest

for assaulting his girlfriend, who was at the center of a number of his

conspiracy theories.

“I knew something was wrong but I literally just did not understand what,” Ms.

Junck, 49, said in a recent interview. “It probably took a year before I

realized my son has a mental illness. This isn’t drug related, this isn’t bad

behavior, this isn’t teenage stuff. This is a serious mental illness.”

Fearful and desperate, she brought her son to an urgent psychiatric center and —

after a five-hour wait — agreed to sign paperwork to have him involuntarily

committed as a danger to himself or others. Her son screamed for her help as he

was carried off. He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and remains in a

residential treatment facility.

This week Erin Adams Goldman, a suicide prevention specialist with a mental

health nonprofit organization in Tucson, is teaching the first local installment

of a course that is being promoted around the country called mental health first

aid, which instructs participants how to recognize and respond to the signs of

mental illness.

A central tenet is that if a person has suspicions about mental illness it is

better to open the conversation, either by approaching the individual directly,

someone else who knows the person well or by asking for a professional

evaluation.

“There is so much fear and mystery around mental illness that people are not

even aware of how to recognize it and what to do about it,” Ms. Goldman said.

“But we get a feeling when something is not right. And what we teach is to

follow your gut and take some action.”

A. G. Sulzberger reported from Tucson,

and Benedict Carey from New York.

Getting Someone to

Psychiatric Treatment

Can Be Difficult and Inconclusive,

NYT, 18.1.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/19/us/19mental.html

Revising Book

on Disorders of the Mind

February 10, 2010

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

Far fewer children would get a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. “Binge eating

disorder” and “hypersexuality” might become part of the everyday language. And

the way many mental disorders are diagnosed and treated would be sharply

revised.

These are a few of the changes proposed on Tuesday by doctors charged with

revising psychiatry’s encyclopedia of mental disorders, the guidebook that

largely determines where society draws the line between normal and not normal,

between eccentricity and illness, between self-indulgence and self-destruction —

and, by extension, when and how patients should be treated.

The eagerly awaited revisions — to be published, if adopted, in the fifth

edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, due in

2013 — would be the first in a decade.

For months they have been the subject of intense speculation and lobbying by

advocacy groups, and some proposed changes have already been widely discussed —

including folding the diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome into a broader category,

autism spectrum disorder.

But others, including a proposed alternative for bipolar disorder in many

children, were unveiled on Tuesday. Experts said the recommendations, posted

online at DSM5.org for public comment, could bring rapid change in several

areas.

“Anything you put in that book, any little change you make, has huge

implications not only for psychiatry but for pharmaceutical marketing, research,

for the legal system, for who’s considered to be normal or not, for who’s

considered disabled,” said Dr. Michael First, a professor of psychiatry at

Columbia University who edited the fourth edition of the manual but is not

involved in the fifth.

“And it has huge implications for stigma,” Dr. First continued, “because the

more disorders you put in, the more people get labels, and the higher the risk

that some get inappropriate treatment.”

One significant change would be adding a childhood disorder called temper

dysregulation disorder with dysphoria, a recommendation that grew out of recent

findings that many wildly aggressive, irritable children who have been given a

diagnosis of bipolar disorder do not have it.

The misdiagnosis led many children to be given powerful antipsychotic drugs,

which have serious side effects, including metabolic changes.

“The treatment of bipolar disorder is meds first, meds second and meds third,”

said Dr. Jack McClellan, a psychiatrist at the University of Washington who is

not working on the manual. “Whereas if these kids have a behavior disorder, then

behavioral treatment should be considered the primary treatment.”

Some diagnoses of bipolar disorder have been in children as young as 2, and

there have been widespread reports that doctors promoting the diagnosis received

consulting and speaking fees from the makers of the drugs.

In a conference call on Tuesday, Dr. David Shaffer, a child psychiatrist at

Columbia, said he and his colleagues on the panel working on the manual “wanted

to come up with a diagnosis that captures the behavioral disturbance and mood

upset, and hope the people contemplating a diagnosis of bipolar for these

patients would think again.”

Experts gave the American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the manual,

predictably mixed reviews. Some were relieved that the task force working on the

manual — which includes neurologists and psychologists as well as psychiatrists

— had revised the previous version rather than trying to rewrite it.

Others criticized the authors, saying many diagnoses in the manual would still

lack a rigorous scientific basis.

The good news, said Edward Shorter, a historian of psychiatry who has been

critical of the manual, is that most patients will be spared the confusion of a

changed diagnosis. But “the bad news,” he added, “is that the scientific status

of the main diseases in previous editions of the D.S.M. — the keystones of the

vault of psychiatry — is fragile.”

To more completely characterize all patients, the authors propose using measures

of severity, from mild to severe, and ratings of symptoms, like anxiety, that

are found as often with personality disorders as with depression.

“In the current version of the manual, people either meet the threshold by

having a certain number of symptoms, or they don’t,” said Dr. Darrel A. Regier,

the psychiatric association’s research director and, with Dr. David J. Kupfer of

the University of Pittsburgh, the co-chairman of the task force. “But often that

doesn’t fit reality. Someone with schizophrenia might have symptoms of insomnia,

of anxiety; these aren’t the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, but they

affect the patient’s life, and we’d like to have a standard way of measuring

them.”

In a conference call on Tuesday, Dr. Regier, Dr. Kupfer and several other

members of the task force outlined their favored revisions. The task force

favored making semantic changes that some psychiatrists have long argued for,

trading the term “mental retardation” for “intellectual disability,” for

instance, and “substance abuse” for “addiction.”

One of the most controversial proposals was to identify “risk syndromes,” that

is, a risk of developing a disorder like schizophrenia or dementia. Studies of

teenagers identified as at high risk of developing psychosis, for instance, find

that 70 percent or more in fact do not come down with the disorder.

“I completely understand the idea of trying to catch something early,” Dr. First

said, “but there’s a huge potential that many unusual, semi-deviant, creative

kids could fall under this umbrella and carry this label for the rest of their

lives.”

Dr. William T. Carpenter, a psychiatrist at the University of Maryland and part

of the group proposing the idea, said it needed more testing. “Concerns about

stigma and excessive treatment must be there,” he said. “But keep in mind that

these are individuals seeking help, who have distress, and the question is,

What’s wrong with them?”

The panel proposed adding several disorders with a high likelihood of entering

the pop vernacular. One, a new description of sex addiction, is

“hypersexuality,” which, in part, is when “a great deal of time is consumed by

sexual fantasies and urges; and in planning for and engaging in sexual

behavior.”

Another is “binge eating disorder,” defined as at least one binge a week for

three months — eating platefuls of food, fast, and to the point of discomfort —

accompanied by severe guilt and plunges in mood.

“This is not the normative overeating that we all do, by any means,” said Dr. B.

Timothy Walsh, a psychiatrist at Columbia and the New York State Psychiatric

Institute who is working on the manual. “It involves much more loss of control,

more distress, deeper feelings of guilt and unhappiness.”

Revising Book on

Disorders of the Mind, NYT, 11.2.2010

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/10/health/10psych.html

Brain Power

Surgery for Mental Ills

Offers Hope and Risk

November 27, 2009

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

One was a middle-aged man who refused to get into the shower. The other was a

teenager who was afraid to get out.

The man, Leonard, a writer living outside Chicago, found himself completely

unable to wash himself or brush his teeth. The teenager, Ross, growing up in a

suburb of New York, had become so terrified of germs that he would regularly

shower for seven hours. Each received a diagnosis of severe obsessive-compulsive

disorder, or O.C.D., and for years neither felt comfortable enough to leave the

house.

But leave they eventually did, traveling in desperation to a hospital in Rhode

Island for an experimental brain operation in which four raisin-sized holes were

burned deep in their brains.

Today, two years after surgery, Ross is 21 and in college. “It saved my life,”

he said. “I really believe that.”

The same cannot be said for Leonard, 67, who had surgery in 1995. “There was no

change at all,” he said. “I still don’t leave the house.”

Both men asked that their last names not be used to protect their privacy.

The great promise of neuroscience at the end of the last century was that it

would revolutionize the treatment of psychiatric problems. But the first real

application of advanced brain science is not novel at all. It is a precise,

sophisticated version of an old and controversial approach: psychosurgery, in

which doctors operate directly on the brain.

In the last decade or so, more than 500 people have undergone brain surgery for

problems like depression, anxiety, Tourette’s syndrome, even obesity, most as a

part of medical studies. The results have been encouraging, and this year, for

the first time since frontal lobotomy fell into disrepute in the 1950s, the Food

and Drug Administration approved one of the surgical techniques for some cases

of O.C.D.

While no more than a few thousand people are impaired enough to meet the strict

criteria for the surgery right now, millions more suffering from an array of

severe conditions, from depression to obesity, could seek such operations as the

techniques become less experimental.

But with that hope comes risk. For all the progress that has been made, some

psychiatrists and medical ethicists say, doctors still do not know much about

the circuits they are tampering with, and the results are unpredictable: some

people improve, others feel little or nothing, and an unlucky few actually get

worse. In this country, at least one patient was left unable to feed or care for

herself after botched surgery.

Moreover, demand for the operations is so high that it could tempt less

experienced surgeons to offer them, without the oversight or support of research

institutions.

And if the operations are oversold as a kind of all-purpose cure for emotional

problems — which they are not, doctors say — then the great promise could

quickly feel like a betrayal.

“We have this idea — it’s almost a fetish — that progress is its own

justification, that if something is promising, then how can we not rush to

relieve suffering?” said Paul Root Wolpe, a medical ethicist at Emory

University.

It was not so long ago, he noted, that doctors considered the frontal lobotomy a

major advance — only to learn that the operation left thousands of patients with

irreversible brain damage. Many promising medical ideas have run aground, Dr.

Wolpe added, “and that’s why we have to move very cautiously.”

Dr. Darin D. Dougherty, director of the division of neurotherapeutics at

Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of psychiatry at

Harvard, put it more bluntly. Given the history of failed techniques, like

frontal lobotomy, he said, “If this effort somehow goes wrong, it’ll shut down

this approach for another hundred years.”

A Last Resort

Five percent to 15 percent of people given diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive

disorder are beyond the reach of any standard treatment. Ross said he was 12

when he noticed that he took longer to wash his hands than most people. Soon he

was changing into clean clothes several times a day. Eventually he would barely

come out of his room, and when he did, he was careful about what he touched.

“It got so bad, I didn’t want any contact with people,” he said. “I couldn’t hug

my own parents.”

Before turning to writing, Leonard was a healthy, successful businessman. Then

he was struck, out of nowhere, with a fear of insects and spiders. He overcame

the phobias, only to find himself with a strong aversion to bathing. He stopped

washing and could not brush his teeth or shave.

“I just looked horrible,” he said. “I had a big, ugly beard. My skin turned

black. I was afraid to be seen out in public. I looked like a street person. If

you were a policeman, you would have arrested me.”

Both tried antidepressants like Prozac, as well as a variety of other

medications. They spent many hours in standard psychotherapy for

obsessive-compulsive disorder, gradually becoming exposed to dreaded situations

— a moldy shower stall, for instance — and practicing cognitive and relaxation

techniques to defuse their anxiety.

To no avail.

“It worked for a while for me, but never lasted,” Ross said. “I mean, I just

thought my life was over.”

But there was one more option, their doctors told them, a last resort. At a

handful of medical centers here and abroad, including Harvard, the University of

Toronto and the Cleveland Clinic, doctors for years have performed a variety of

experimental procedures, most for O.C.D. or depression, each guided by

high-resolution imaging technology. The companies that make some of the devices

have supported the research, and paid some of the doctors to consult on

operations.

In one procedure, called a cingulotomy, doctors drill into the skull and thread

wires into an area called the anterior cingulate. There they pinpoint and

destroy pinches of tissue that lie along a circuit in each hemisphere that

connects deeper, emotional centers of the brain to areas of the frontal cortex,

where conscious planning is centered.

This circuit appears to be hyperactive in people with severe O.C.D., and imaging

studies suggest that the surgery quiets that activity. In another operation,

called a capsulotomy, surgeons go deeper, into an area called the internal

capsule, and burn out spots in a circuit also thought to be overactive.

An altogether different approach is called deep brain stimulation, or D.B.S., in

which surgeons sink wires into the brain but leave them in place. A

pacemaker-like device sends a current to the electrodes, apparently interfering

with circuits thought to be hyperactive in people with obsessive-compulsive

disorder (and also those with severe depression). The current can be turned up,

down or off, so deep brain stimulation is adjustable and, to some extent,

reversible.

In yet another technique, doctors place the patient in an M.R.I.-like machine

that sends beams of radiation into the skull. The beams pass through the brain

without causing damage, except at the point where they converge. There they burn

out spots of tissue from O.C.D.-related circuits, with similar effects as the

other operations. This option, called gamma knife surgery, was the one Leonard

and Ross settled on.

The institutions all have strict ethical screening to select candidates. The

disorder must be severe and disabling, and all standard treatments exhausted.

The informed-consent documents make clear that the operation is experimental and

not guaranteed to succeed.

Nor is desperation by itself sufficient to qualify, said Richard Marsland, who

oversees the screening process at Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I., which

works with surgeons at Rhode Island Hospital, where Leonard and Ross had the

operation.

“We get hundreds of requests a year and do only one or two,” Mr. Marsland said.

“And some of the people we turn down are in bad shape. Still, we stick to the

criteria.”

For those who have successfully recovered from surgery, this intensive screening

seems excessive. “I know why it’s done, but this is an operation that could make

the difference between life and death for so many people,” said Gerry Radano,

whose book “Contaminated: My Journey Out of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder”

(Bar-le-Duc Books, 2007), recounts her own suffering and long recovery from

surgery. She also has a Web site, freeofocd.com, where people from around the

world consult with her.

But for the doctors running the programs, this screening is crucial. “If

patients are poorly selected or not followed well, there’ll be an increasing

number of bad outcomes, and the promise of this field will wither away,” said

Dr. Ben Greenberg, the psychiatrist in charge of the program at Butler.

Dr. Greenberg said about 60 percent of patients who underwent either gamma knife

surgery or deep brain stimulation showed significant improvement, and the rest

showed little or no improvement. For this article, he agreed to put a reporter

in touch with one — Leonard — who did not have a good experience.

The Danger of Optimism

The true measure of an operation, medical ethicists say, is its overall effect

on a person’s life, not only on specific symptoms.

In the early days of psychosurgery, after World War II, doctors published scores

of papers detailing how lobotomy relieved symptoms of mental distress. In 1949,

the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz won the Nobel Prize in medicine for

inventing the procedure.

But careful follow-up painted a darker picture: of people who lost motivation,

who developed the helpless indifference dramatized by the post-op rebel McMurphy

in Ken Kesey’s novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” played by Jack Nicholson

in the 1975 movie.

The newer operations pinpoint targets on specific, precisely mapped circuits,

whereas the frontal lobotomy amounted to a crude slash into the brain behind the

eyes, blindly mangling whatever connections and circuits were in the way. Still,

there remain large gaps in doctors’ understanding of the circuits they are

operating on.

In a paper published last year, researchers at the Karolinska Institute in

Sweden reported that half the people who had the most commonly offered

operations for obsessive-compulsive disorder showed symptoms of apathy and poor

self-control for years afterward, despite scoring lower on a measure of O.C.D.

severity.

“An inherent problem in most research is that innovation is driven by groups

that believe in their method, thus introducing bias that is almost impossible to

avoid,” Dr. Christian Ruck, the lead author of the paper, wrote in an e-mail

message. The institute’s doctors, who burned out significantly more tissue than

other centers did, no longer perform the operations, partly, Dr. Ruck said, as a

result of his findings.

In the United States, at least one patient has suffered disabling brain damage

from an operation for O.C.D. The case led to a $7.5 million judgment in 2002

against the Ohio hospital that performed the procedure. (It is no longer offered

there.)

Most outcomes, whether favorable or not, have had less remarkable immediate

results. The brain can take months or even years to fully adjust after the

operations. The revelations about the people treated at Karolinska “underscore

the importance of face-to-face assessments of adverse symptoms,” Dr. Ruck and

his co-authors concluded.

The Long Way Back

Ross said he felt no difference for months after surgery, until the day his

brother asked him to play a video game in the basement, and down the stairs he

went.

“I just felt like doing it,” he said. “I would never have gone down there

before.”

He said the procedure seemed to give the psychotherapy sessions a chance to

work, and last summer he felt comfortable enough to stop them. He now spends his

days studying, going to class, playing the odd video game to relax. He has told

friends about the operation, he said, “and they’re O.K. with it — they know the

story.”

Leonard is still struggling, for reasons no one understands. He keeps odd hours,

working through most nights and sleeping much of the day. He is not unhappy, he

said, but he has the same aversion to washing and still lives like a hermit.

“I still don’t know why I’m like this, and I would still try anything that could

help,” he said. “But at this point, obviously, I’m skeptical of the efficacy of

surgery, at least for me.”

Ms. Radano, who wrote the book about her recovery, said the most important thing

about the surgery was that it gave people a chance. “That’s all people in this

situation want, and I know because I was there,” she said while getting into her

car on a recent afternoon.

On the passenger seat was a container of decontaminating hand wipes. She pointed

and laughed. “See? You’re never completely out.”

Surgery for Mental Ills

Offers Hope and Risk, NYT, 27.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/27/health/research/27brain.html

Brendan Smialowski for The New York Times

Dr. Darrel A. Regier

is co-chairman of a panel compiling the latest

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Psychiatrists Revising the Book

of Human Troubles

NYT

18 December 2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/18/

health/18psych.html

Psychiatrists

Revising the Book of Human Troubles

December 18, 2008

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

The book is at least three

years away from publication, but it is already stirring bitter debates over a

new set of possible psychiatric disorders.

Is compulsive shopping a mental problem? Do children who continually recoil from

sights and sounds suffer from sensory problems — or just need extra attention?

Should a fetish be considered a mental disorder, as many now are?

Panels of psychiatrists are hashing out just such questions, and their answers —

to be published in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders — will have consequences for insurance reimbursement, research

and individuals’ psychological identity for years to come.

The process has become such a contentious social and scientific exercise that

for the first time the book’s publisher, the American Psychiatric Association,

has required its contributors to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

The debate is particularly intense because the manual is both a medical

guidebook and a cultural institution. It helps doctors make a diagnosis and

provides insurance companies with diagnostic codes without which the insurers

will not reimburse patients’ claims for treatment.

The manual — known by its initials and edition number, DSM-V — often organizes

symptoms under an evocative name. Labels like obsessive-compulsive disorder have

connotations in the wider culture and for an individual’s self-perception.

“This is not cardiology or nephrology, where the basic diseases are well known,”

said Edward Shorter, a leading historian of psychiatry whose latest book,

“Before Prozac,” is critical of the manual. “In psychiatry no one knows the

causes of anything, so classification can be driven by all sorts of factors” —

political, social and financial.

“What you have in the end,” Mr. Shorter said, “is this process of sorting the

deck of symptoms into syndromes, and the outcome all depends on how the cards

fall.”

Psychiatrists involved in preparing the new manual contend that it is too early

to say for sure which cards will be added and which dropped.

The current edition of the manual, which was published in 2000, describes 283

disorders — about triple the number in the first edition, published in 1952.

The scientists updating the manual have been meeting in small groups focusing on

categories like mood disorders and substance abuse — poring over the latest

scientific studies to clarify what qualifies as a disorder and what might

distinguish one disorder from another. They have much more work to do, members

say, before providing recommendations to a 28-member panel that will gather in

closed meetings to make the final editorial changes.

Experts say that some of the most crucial debates are likely to include gender

identity, diagnoses of illness involving children, and addictions like shopping

and eating.

“Many of these are going to involve huge fights, I expect,” said Dr. Michael

First, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia who edited the fourth edition of

the manual but is not involved in the fifth.

One example, Dr. First said, is binge eating, now in the manual’s appendix as a

tentative category.

“A lot of people want that included in the manual,” Dr. First said, “and there’s

some research out there, some evidence that drugs are helpful. But binge eating

is also a normal behavior, and you run the risk of labeling up to 30 percent of

people with a disorder they don’t really have.”

The debate over gender identity, characterized in the manual as “strong and

persistent cross-gender identification,” is already burning hot among

transgender people. Soon after the psychiatric association named the group of

researchers working on sexual and gender identity, advocates circulated online