|

Vocapedia >

Men,

Women > Love > Infidelity

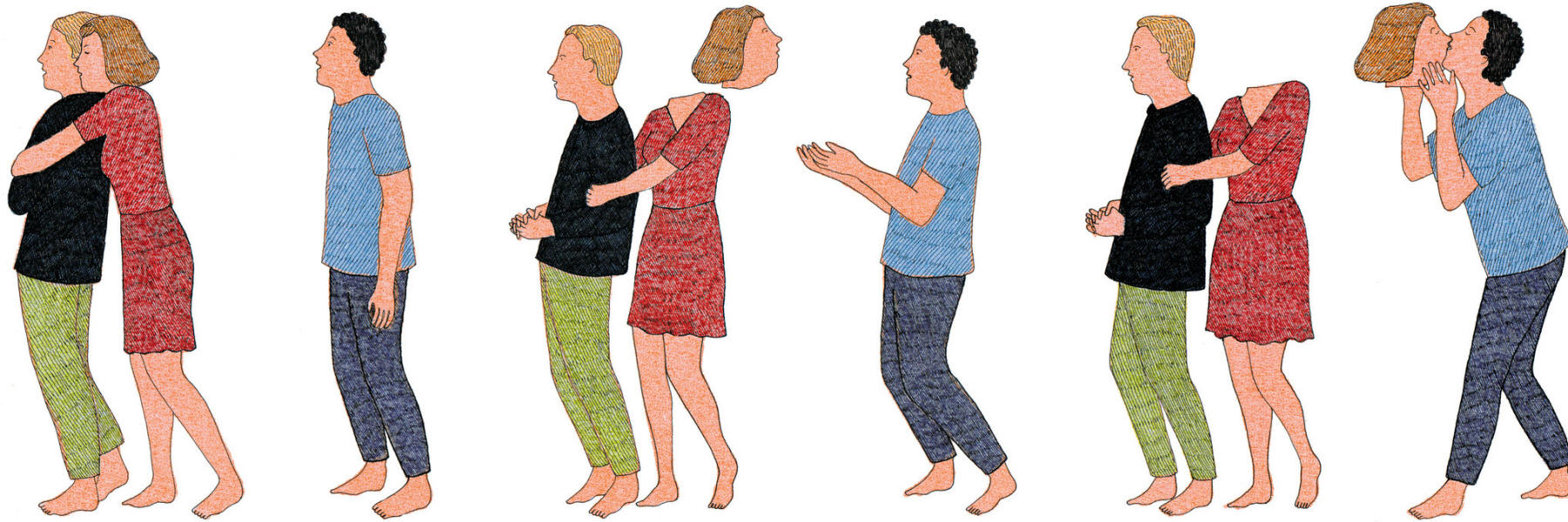

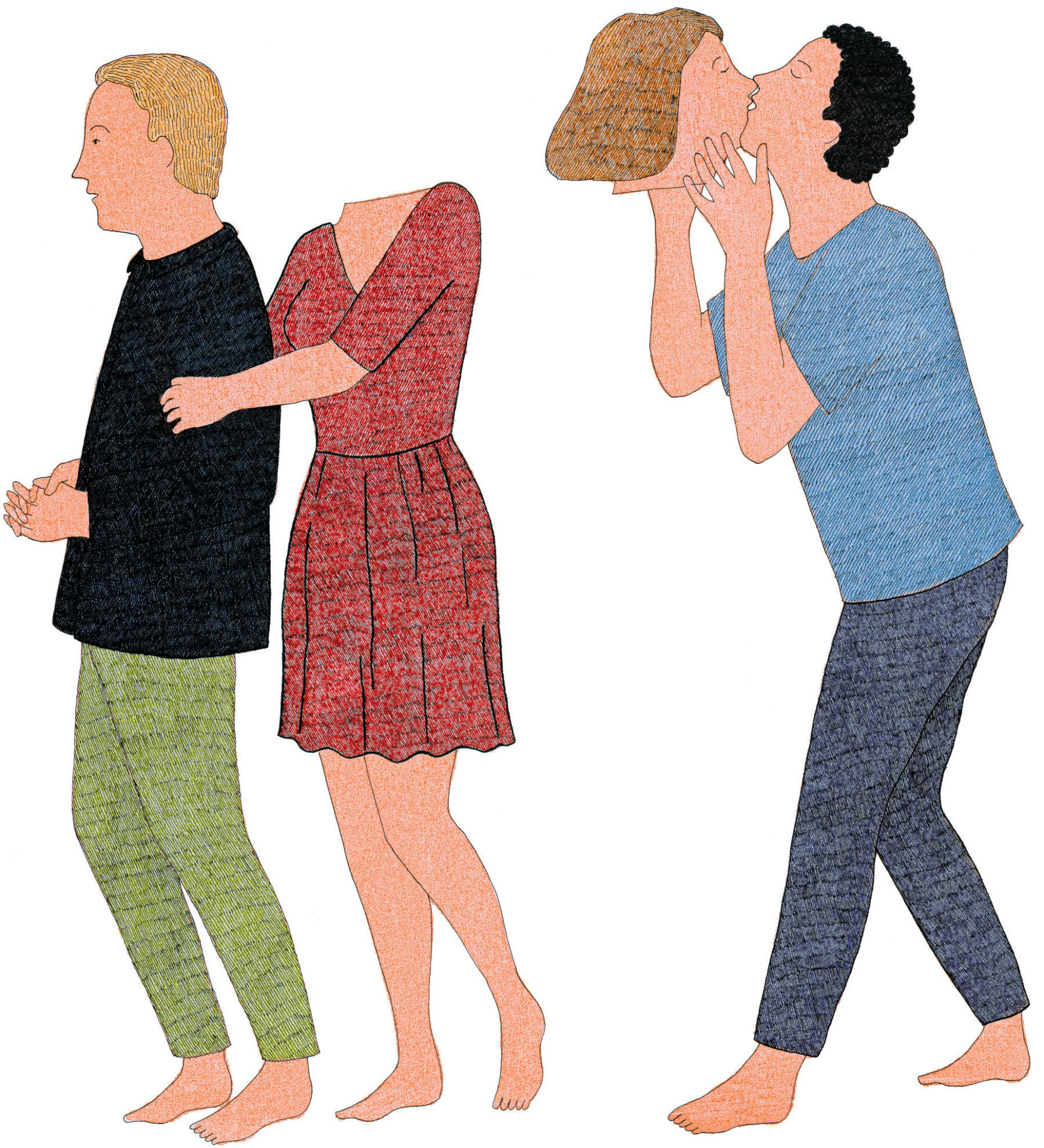

Illustration: Marion Fayolle

Infidelity Lurks in Your Genes

NYT

MAY 22, 2015

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/

opinion/sunday/infidelity-lurks-in-your-genes.html

Marion Fayolle

Infidelity Lurks in Your Genes

NYT

MAY 22, 2015

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/

opinion/sunday/infidelity-lurks-in-your-genes.html

be out of love

with N

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/oct/13/

unfaithful-fiance-flings-mariella-frostrup

be

unfaithful to N

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/oct/13/

unfaithful-fiance-flings-mariella-frostrup

unfaithful

affair / liaison / indiscretion / conversation

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/apr/23/

my-perfect-affair-sex-lover-extramarital-secret

fling

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/oct/13/

unfaithful-fiance-flings-mariella-frostrup

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/07/

opinion/07dowd.html

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2008/jul/19/

familyandrelationships5

infidelity USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/08/19/

g-s1-17587/once-a-cheater-always-a-cheater-

busting-3-common-myths-about-infidelity

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/

opinion/sunday/infidelity-lurks-in-your-genes.html

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/24/

when-the-best-sex-is-extramarital/

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/16/

opinion/the-petraeus-effect-on-military-marriage.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/03/

magazine/infidelity-will-keep-us-together.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/28/

health/28well.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/

opinion/21druckerman.html

marital infidelities

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/20/

sports/golf/20woods.html

marital infidelity

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/

opinion/sunday/infidelity-lurks-in-your-genes.html

affair

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/29/us/

politics/cain-accused-of-affair-by-ginger-white.html

have an affair

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2012/jun/17

/my-father-having-an-affair

have an affair

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/15/

magazine/should-i-tell-my-friends-husband-that-shes-having-an-affair.html

extramarital

USA

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/24/

when-the-best-sex-is-extramarital/

extramarital affair / affair

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/

opinion/21druckerman.html

affair / love affair / secret affair

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/mar/01/

i-was-other-woman-married-men

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2008/sep/07/relationships.women

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/jul/20/

familyfinance.money

conversation / indiscretion / affair

passionate love affair

adultery

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/04/

hanif-kureishi-praise-adultery-week-end

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/sep/15/

history.biography

unfaithful / be

unfaithful to N

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/oct/13/

unfaithful-fiance-flings-mariella-frostrup

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/mar/13/

john-terry-ashley-cole-tiger-woods-me

cheat

on N USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/28/

health/28well.html

cheater

UK

https://www.npr.org/2024/08/19/

g-s1-17587/once-a-cheater-always-a-cheater-

busting-3-common-myths-about-infidelity

deceive

in a compromising

position with N

dalliances

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/oct/02/

david-letterman-sex-blackmail-plot

mistress

ex-mistress

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2006/apr/30/uk.

labour1

fiancé

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/oct/13/

unfaithful-fiance-flings-mariella-frostrup

Corpus of news articles

Men, Women > Love > Infidelity

Infidelity

Lurks in Your Genes

MAY 22, 2015

The New York

Times

SundayReview

Contributing Op-Ed Writer

Richard A.

Friedman

AMERICANS

disapprove of marital infidelity. Ninety-one percent of them find it morally

wrong, more than the number that reject polygamy, human cloning or suicide,

according to a 2013 Gallup poll.

Yet the number of Americans who actually cheat on their partners is rather

substantial: Over the past two decades, the rate of infidelity has been pretty

constant at around 21 percent for married men, and between 10 to 15 percent for

married women, according to the General Social Survey at the University of

Chicago’s independent research organization, NORC.

We are accustomed to thinking of sexual infidelity as a symptom of an unhappy

relationship, a moral flaw or a sign of deteriorating social values. When I was

trained as a psychiatrist we were told to look for various emotional and

developmental factors — like a history of unstable relationships or a

philandering parent — to explain infidelity.

But during my career, many of the questions we asked patients were found to be

insufficient because for so much behavior, it turns out that genes, gene

expression and hormones matter a lot.

Now that even appears to be the case for infidelity.

We have long known that men have a genetic, evolutionary impulse to cheat,

because that increases the odds of having more of their offspring in the world.

But now there is intriguing new research showing that some women, too, are

biologically inclined to wander, although not for clear evolutionary benefits.

Women who carry certain variants of the vasopressin receptor gene are much more

likely to engage in “extra pair bonding,” the scientific euphemism for sexual

infidelity.

Brendan P. Zietsch, a psychologist at the University of Queensland, Australia,

has tried to determine whether some people are just more inclined toward

infidelity. In a study of nearly 7,400 Finnish twins and their siblings who had

all been in a relationship for at least one year, Dr. Zietsch looked at the link

between promiscuity and specific variants of vasopressin and oxytocin receptor

genes. Vasopressin is a hormone that has powerful effects on social behaviors

like trust, empathy and sexual bonding in humans and other animals. So it makes

sense that mutations in the vasopressin receptor gene — which can alter its

function — could affect human sexual behavior.

He found that 9.8 percent of men and 6.4 percent of women reported that they had

two or more sexual partners in the previous year. His study, published last year

in Evolution and Human Behavior, found a significant association between five

different variants of the vasopressin gene and infidelity in women only and no

relationship between the oxytocin genes and sexual behavior for either sex. That

was impressive: Forty percent of the variation in promiscuous behavior in women

could be attributed to genes. That is surprising since, as Dr. Zietsch points

out, there are so many other factors that are necessary for promiscuous

encounters, like circumstance and the availability of a willing and able

partner. Although this is the largest and best study on this, it’s not clear why

there was no relationship between the vasopressin gene and promiscuous behavior

in men.

Other studies confirm that oxytocin and vasopressin are linked to partner

bonding, which bears on the question of promiscuity since emotional bonding is,

in a sense, the inverse of promiscuity. Hasse Walum at the Karolinska Institute

in Stockholm found that in women, but not in men, there is a significant

association between one variant of the oxytocin receptor gene and marital

discord and lack of affection for one’s partner. In contrast, there was a

significant correlation in men between a specific variant of the vasopressin

receptor gene and lower marital quality reported by their spouses.

Now, before you run out and get your prospective partner genotyped for his or

her vasopressin and oxytocin receptor genes, two caveats: Correlation is not the

same as causation; there are undoubtedly many unmeasured factors that contribute

to infidelity. And rarely does a simple genetic variant determine behavior.

Still, there is a good reason to take these findings seriously: Data in animals

confirm that these two hormones are significant players when it comes to sexual

behavior. An intriguing clue came from the pioneering work of Dr. Thomas R.

Insel, now the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, who studied

the effects of vasopressin and oxytocin in a little rodent called the vole. It

turns out that there are two closely related species of voles: montane voles,

which are sexually promiscuous, and prairie voles, which are sexually monogamous

and raise their extended families in burrows.

After sex, prairie voles quickly develop a selective and enduring preference for

their mate, while mating for montane voles is more of a one-night stand.

What Dr. Insel described is that the strikingly different sexual behavior of

these two species of voles reflects the action of vasopressin in their brains.

The vasopressin receptors in the montane and prairie voles are in completely

different brain regions so that when these receptors are stimulated by

vasopressin, there are very different behavioral effects.

When vasopressin is injected directly into the brain of the monogamous male

prairie vole, it triggers pair bonding; in contrast, blocking the vasopressin

receptors inhibits monogamy, but does nothing to stop sexual activity. In other

words, vasopressin promotes social bonding, and blocking the activity of this

hormone encourages social promiscuity.

In the monogamous prairie voles, the vasopressin receptors are close to the

brain’s reward center, but in the philandering montane voles, these same

receptors are mostly found in the amygdala, a brain region that is critical to

processing anxiety and fear.

So mating for the prairie voles activates the pleasurable reward pathway, which

reinforces mating and promotes attachment and thus monogamy. For the promiscuous

montane voles, sex has little effect on attachment; any vole will do.

It is even possible experimentally to take a home-wrecking montane vole and make

him behave like a family-oriented prairie vole. Using a virus as a delivery

vehicle to transmit the vasopressin receptor gene, it’s easy to artificially

boost the number of vasopressin receptors in the brain’s reward center, and make

a male vole behave monogamously. The story for female voles is similar except

that it is oxytocin, not vasopressin, that triggers monogamous behavior.

We don’t yet know from human studies whether the vasopressin receptor genes that

are linked with infidelity actually make the brain less responsive to these

hormones, but given the animal data, it is plausible.

EXPERIMENTS in

which oxytocin and vasopressin are directly administered to humans show these

hormones have effects that go beyond sex; they appear to increase trust and

social bonding. In one study, for example, healthy subjects were randomly given

either intranasal oxytocin or a placebo and then played a trust game. In this

game, the two subjects either act as an investor or a trustee. The investor

first has the chance of choosing a costly trusting action by giving money to the

trustee. Then the trustee can either honor the trust by returning a portion of

the money or violate it by not sharing the money. Those who play under the

influence of oxytocin continue to trust and make generous monetary offers in

response to betrayal, while subjects getting a placebo become less trusting and

stingier after getting burned. Oxytocin appears to make us more socially

trusting — even in situations where it may not be in our best interest to do so.

In one study of men, giving vasopressin enhanced the subjects’ memory for both

happy and angry faces compared with a placebo, which implies that vasopressin

could boost social affiliation and aggressive behavior since it increased social

and emotional learning.

These findings also suggest potential therapeutic uses for oxytocin and

vasopressin for people who have either a deficit or an excess of trust and

social bonding. Autism is an example of a deficit, and indeed there is

preliminary evidence that oxytocin may have some beneficial prosocial effects in

this disorder. In contrast, Williams syndrome is a rare genetic illness in which

kids are pathologically trusting and indiscriminately befriend complete

strangers. The disorder is associated with baseline oxytocin levels that are on

average three times above normal, so a drug that blocks oxytocin may curb their

excessive trust.

If you have an Orwellian bent, you’ve probably already imagined the mischief you

might do with these two hormones. You could surreptitiously make a potential

investor more trusting or encourage a monogamous impulse in a partner who you

suspect is cheating. All you need is aerosolized oxytocin or vasopressin,

perhaps in a spiked air freshener or perfume. Kidding, of course, but you get

the idea.

Sexual monogamy is distinctly unusual in nature: Humans are among the 3 to 5

percent of mammalian species that practice monogamy, along with the swift fox

and beaver — but even in these species, infidelity has been commonly observed.

The evolutionary benefit of promiscuity for men is pretty straightforward: The

more sexual partners you have, the greater your potential reproductive success.

But women’s reproductive capacity is more limited by biology. So what’s in it

for women? There may be no clear evolutionary advantage to female infidelity,

but sex has never just been about procreation. Cheating can be intensely

pleasurable because, among other things, it involves novelty and a degree of

sensation seeking, behaviors that activate the brain’s reward circuit. Sex,

money and drugs, among other things, trigger the release of dopamine from this

circuit, which conveys not just a sense of pleasure but tells your brain this is

an important experience worth remembering and repeating. And, of course, humans

vary widely in their taste for novelty.

In a 2010 study of 181 young, healthy adults, Justin R. Garcia, then at

Binghamton University, found that subjects who carried a variant of one dopamine

receptor subtype, the D4 receptor, were 50 percent more likely to report sexual

infidelity. This D4 genetic variant has reduced binding for dopamine, which

implies that these individuals walk around at baseline feeling less stimulated

and hungrier for novelty than those lacking this genetic variant.

So do we get a moral pass if we happen to carry one of these “infidelity” genes?

Hardly. We don’t choose our genes and can’t control them (yet), but we can

usually decide what we do with the emotions and impulses they help create. But

it is important to acknowledge that we live our lives on a very uneven genetic

playing field. A friend of mine, who is a bisexual woman in her early 50s,

recently told me about her long history of sexual exploits outside of her

marriage. She hadn’t had sex with her partner for many years, although she

wanted to — “she just wasn’t into it anymore,” she told me. One day, she ran

into a man she had known years earlier and, not long after, struck up an affair

with him. “He was really into me and the sex was so exciting that I just went

with it and decided not to say anything to my partner.” Here were all the usual

factors that we know set the stage for extramarital sex: marital discord, sexual

dissatisfaction and emotional alienation in the primary relationship. My friend

was well aware of them and this was how she explained the basis of her own

infidelity.

But when she told me that she’d cheated early on in her relationship with her

partner, at least once when things were going well, I realized that she probably

had a propensity for sexual exploration that seemed in some ways independent of

the emotional status of her relationships.

For some, there is little innate temptation to cheat; for others, sexual

monogamy is an uphill battle against their own biology.

A professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College and a

contributing opinion writer.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up

for the Opinion Today newsletter.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on May 24, 2015, on page SR1 of the

National edition with the headline: Infidelity Lurks in Your Genes.

Infidelity

Lurks in Your Genes,

NYT,

MAY 22, 2015,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/24/

opinion/sunday/infidelity-lurks-in-your-genes.html

Love, Sex

and the Changing Landscape

of Infidelity

October 28, 2008

The New York Times

By TARA PARKER-POPE

If you cheated on your spouse, would you admit it to a

researcher?

That question is one of the biggest challenges in the scientific study of

marriage, and it helps explain why different studies produce different estimates

of infidelity rates in the United States.

Surveys conducted in person are likely to underestimate the real rate of

adultery, because people are reluctant to admit such behavior not just to their

spouses but to anyone.

In a study published last summer in The Journal of Family Psychology, for

example, researchers from the University of Colorado and Texas A&M surveyed

4,884 married women, using face-to-face interviews and anonymous computer

questionnaires. In the interviews, only 1 percent of women said they had been

unfaithful to their husbands in the past year; on the computer questionnaire,

more than 6 percent did.

At the same time, experts say that surveys appearing in sources like women’s

magazines may overstate the adultery rate, because they suffer from what

pollsters call selection bias: the respondents select themselves and may be more

likely to report infidelity.

But a handful of new studies suggest surprising changes in the marital

landscape. Infidelity appears to be on the rise, particularly among older men

and young couples. Notably, women appear to be closing the adultery gap: younger

women appear to be cheating on their spouses nearly as often as men.

“If you just ask whether infidelity is going up, you don’t see really impressive

changes,” said David C. Atkins, research associate professor at the University

of Washington Center for the Study of Health and Risk Behaviors. “But if you

magnify the picture and you start looking at specific gender and age cohorts, we

do start to see some pretty significant changes.”

The most consistent data on infidelity come from the General Social Survey,

sponsored by the National Science Foundation and based at the University of

Chicago, which has used a national representative sample to track the opinions

and social behaviors of Americans since 1972. The survey data show that in any

given year, about 10 percent of married people — 12 percent of men and 7 percent

of women — say they have had sex outside their marriage.

But detailed analysis of the data from 1991 to 2006, to be presented next month

by Dr. Atkins at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

conference in Orlando, show some surprising shifts. University of Washington

researchers have found that the lifetime rate of infidelity for men over 60

increased to 28 percent in 2006, up from 20 percent in 1991. For women over 60,

the increase is more striking: to 15 percent, up from 5 percent in 1991.

The researchers also see big changes in relatively new marriages. About 20

percent of men and 15 percent of women under 35 say they have ever been

unfaithful, up from about 15 and 12 percent respectively.

Theories vary about why more people appear to be cheating. Among older people, a

host of newer drugs and treatments are making it easier to be sexual, and in

some cases unfaithful — Viagra and other remedies for erectile dysfunction,

estrogen and testosterone supplements to maintain women’s sex drive and vaginal

health, even advances like better hip replacements.

“They’ve got the physical health to express their sexuality into old age,” said

Helen E. Fisher, research professor of anthropology at Rutgers and the author of

several books on the biological and evolutionary basis of love and sex.

In younger couples, the increasing availability of pornography on the Internet,

which has been shown to affect sexual attitudes and perceptions of “normal”

behavior, may be playing a role in rising infidelity.

But it is the apparent change in women’s fidelity that has sparked the most

interest among relationship researchers. It is not entirely clear if the

historical gap between men and women is real or if women have just been more

likely to lie about it.

“Is it that men are bragging about it and women are lying to everybody including

themselves?” Dr. Fisher asked. “Men want to think women don’t cheat, and women

want men to think they don’t cheat, and therefore the sexes have been playing a

little psychological game with each other.”

Dr. Fisher notes that infidelity is common across cultures, and that in hunting

and gathering societies, there is no evidence that women are any less adulterous

than men. The fidelity gap may be explained more by cultural pressures than any

real difference in sex drives between men and women. Men with multiple partners

typically are viewed as virile, while women are considered promiscuous. And

historically, women have been isolated on farms or at home with children, giving

them fewer opportunities to be unfaithful.

But today, married women are more likely to spend late hours at the office and

travel on business. And even for women who stay home, cellphones, e-mail and

instant messaging appear to be allowing them to form more intimate

relationships, marriage therapists say. Dr. Frank Pittman, an Atlanta

psychiatrist who specializes in family crisis and couples therapy, says he has

noticed more women talking about affairs centered on “electronic” contact.

“I see a changing landscape in which the emphasis is less on the sex than it is

on the openness and intimacy and the revelation of secrets,” said Dr. Pittman,

the author of “Private Lies: Infidelity and the Betrayal of Intimacy” (Norton,

1990). “Everybody talks by cellphone and the relationship evolves because you

become increasingly distant from whomever you lie to, and you become

increasingly close to whomever you tell the truth to.”

While infidelity rates do appear to be rising, a vast majority of people still

say adultery is wrong, and most men and women do not appear to be unfaithful.

Another problem with the data is that it fails to discern when respondents

cheat: in a troubled time in the marriage, or at the end of a failing

relationship.

“It’s certainly plausible that women might have increased their relative rate of

infidelity over time,” said Edward O. Laumann, professor of sociology at the

University of Chicago. “But it isn’t going to be a huge number. The real thing

to talk about is where are they in terms of their relationship and the marital

bond.”

The General Social Survey data also show some encouraging trends, said John P.

Robinson, professor of sociology and director of the Americans’ Use of Time

project at the University of Maryland. One notable shift is that couples appear

to be spending slightly more time together. And married men and women also

appear to have the most active sex lives, reporting sex with their spouse 58

times a year, a little more than once a week.

“We’ve looked at that as good news,” Dr. Robinson said.

Love, Sex and the Changing Landscape of

Infidelity,

NYT,

28.10.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/28/

health/28well.html

Grant Shaffer

After the End of the Affair

NYT

21 March 2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/

opinion/21druckerman.html

Op-Ed Contributor

After the End of the Affair

March 21, 2008

The New York Times

By PAMELA DRUCKERMAN

Paris

AS Eliot Spitzer and his wife, Silda, rattle around their Fifth Avenue

apartment, it’s a pretty safe guess that their life as a couple is hell.

They may want to get some marital advice from Mr. Spitzer’s replacement as New

York governor, David A. Paterson, who said Tuesday that his own extramarital

affairs ended several years ago and that his marriage was back on track. But the

Spitzers are less than two weeks past D-Day. In the parlance of American couples

recovering from adultery, “D-Day” is the day you discover your spouse has been

cheating on you. And as with the birth of Jesus, time is reset from there.

The reason why everything from the puffiness of Mrs. Spitzer’s eyes to the

number of inches between her and her husband at press conferences have been

scrutinized is that we treat D-Days like natural disasters. The American

Association for Marriage and Family Therapy has warned, “The reactions of the

betrayed spouse resemble the post-traumatic stress symptoms of the victims of

traumatic events.”

No comparison seems big enough. “9/11 always reminds me of how it felt — one

floor collapsing into another,” said a woman in her 40s who lives near Seattle.

Another woman, writing in an Internet chat room, compared her husband’s affair

to the Asian tsunami of 2004, which killed a quarter of a million people. The

jargon of people recovering from adultery sounds like wartime code: X.O.W. is

the “ex-other woman,” O.N.S. is a “one-night stand,” and N.P.D. is the often

diagnosed “narcissistic personality disorder.” A “cake man” is a husband who

wants to have his wife and his mistress, too.

Married people the world over are devastated to discover that their partners

have been, as the Dutch say, pinching the cat in the dark. French wives were

shocked when I suggested that it was their custom to look the other way. (Even

French first ladies don’t do this anymore.) Wives from sub-Saharan Africa, a

part of the world with the highest levels of male infidelity, told me how they

went running down the street after their husbands, begging them to sleep at

home.

But American D-Days are even worse because we have such improbably high

standards for marriage. If your spouse cheats, you’ve been living a lie.

Americans describing their D-Day experiences say that they weren’t just shocked,

jealous and profoundly upset, but that their whole view of the world had

collapsed. “It robs you of your past,” one husband said. “What is real? What is

fake?”

We Americans are particularly preoccupied with honesty. We’re the only country

that peddles the idea that “It’s not the sex, it’s the lying.” (In France, it’s

not the lying, it’s the sex.) America is also the only place I found that has a

one-strike rule on fidelity: if someone cheats, the marriage is kaput.

We might not strictly hold ourselves to this script, but we expect our

politicians to follow it. That’s why people doubted that Bill and Hillary

Clinton could have a “real” marriage if she stayed with him after the Lewinsky

affair. It’s why a reporter felt free to shout, “Silda, are you leaving him?” at

the Spitzers last week. And it’s why David Paterson took pains to say that he

and his wife were still very much in love and that he’s now faithful, despite

the fact that he had had “a number of women” (and his wife had cheated, too).

Political spouses have some of the worst D-Days, because they have them in

public. Dina Matos McGreevey, the estranged wife of New Jersey’s former

governor, says she found out her husband was gay just hours before he told the

world. Mrs. Spitzer discovered her husband’s apparent penchant for call girls

only the night before he announced his “private matter” to the press.

Mr. Paterson said he and his wife had gone into counseling, another stalwart of

America’s adultery culture. Our marriage-industrial complex offers tens of

thousands of couples therapists, as well as support groups for wounded spouses

and sexual addicts, “accountability partners” for straying church members, and

countless seminars and healing weekends, many led by “reformed” cheaters and

their spouses.

Because lying is the problem, truth-telling has become our national cure. On the

frenetically active SurvivingInfidelity.com, “Erica” says she spent 20 months

interrogating her husband about his affair, and then “with the aid of my master

calendar and 1000+ emails, the photo albums, Visa receipts and his old expense

reports, he and I set out to put all of those two and a half years of infidelity

on a timeline.”

Not surprisingly, all this makes recovery a long and often unhealthy process. A

woman in Tennessee told me that she had gained 60 pounds since her husband found

out she had been sleeping with a co-worker, in part because the couple now

spends most of their free time on the couch rehashing the affair. “Neither of us

cries as much as we used to, because of the antidepressants,” her husband said.

The fact is that many couples, like this one, end up staying together. The

Patersons did. The Spitzers might, too, if we give them a chance. Whatever Eliot

Spitzer’s and David Paterson’s sins, just surviving infidelity in America may be

punishment enough.

Pamela Druckerman is the author of

“Lust in Translation: Infidelity From

Tokyo to Tennessee.”

After the End of the

Affair,

NYT, 21.3.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/

opinion/21druckerman.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

men, women,

gender identity,

glass ceiling, feminism,

prostitution,

gay / LGBTQ rights,

human connection,

friendship,

relationships,

dating, love, sex,

marriage, divorce

family

violence against women and girls

worldwide

contraception,

abortion,

pregnancy, birth,

life, life expectancy,

getting older / aging,

death

www > online relationships

Health > HIV -

AIDS

religions > Christians > Popes

|