|

Vocapedia

>

Arts >

Books > Writers,

Awards

Writer

W. H. Auden (1907-1973)

Date taken: 1956

Photograph:

Alfred Eisenstaedt

Life Images

http://images.google.com/hosted/life/

71d4c1eabcb8c6ee.html

- broken link

free speech UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/aug/15/

salman-rushdie-free-speech-tyranny-satanic-verses

write

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/global/audioslideshow/2009/jan/29/

johnupdike

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/dec/12/

john-mortimer-why-write-rumpole

handwrite UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/oct/12/

the-story-behind-the-spy-stories-show-reveals-secrets-of-john-le-carre-craft

writer USA

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/11/22/

opinion/brain-traumatic-injury-writing.html

https://www.nytimes.com/

article/books-race-america.html - June 25, 2020

https://www.npr.org/2016/01/09/

462437823/as-writers-wages-wane-in-digital-chapter-authors-pen-demands

genre writer

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/

books/jack-vance-writer-of-the-fantastical-dies-at-96.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/19/

magazine/19Vance-t.html

short story writer

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/23/

books/mary-ward-brown-95-award-winning-short-story-writer-dies.html

crime writer USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/14/

arts/14gores.html

cookbook writer UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/mar/15/

nigella-lawson-why-i-write-cookbooks

biographer UK / USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/

books/park-honan-a-biographer-of-authors-is-dead-at-86.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/

books/justin-kaplan-literary-biographer-dies-at-88.html

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/aug/20/

margaret-thatcher-biography-edinburgh

memoirist USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/23/

books/review/assume-nothing-tanya-selvaratnam.html

writing UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/07/

tom-mccarthy-death-writing-james-joyce-working-google

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2013/jan/20/

david-hare-interview-judas-kiss

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/sep/07/

lawrence-norfolk-life-in-writing

women's writing USA

https://www.npr.org/2018/04/21/

600902444/how-to-suppress-womens-writing-

three-decades-old-and-still-sadly-relevant

crime writing UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2011/nov/04/

pd-james-life-in-writing

original writing UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

original-writing

plagiarism UK

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/oct/27/

how-common-is-plagiarism-in-the-publishing-industry

New Grub Street

(...)

refers to the London street that,

in the age of Samuel Johnson

and Laurence Sterne (...),

was synonymous with hack writing.

By the 1890s,

Grub Street no longer existed,

though hack writing,

of course, never goes away,

with timeless imperatives.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/31/

100-best-novels-new-grub-street-gissing

American prose USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/14/

books/review/cormac-mccarthy.html

playwright UK

http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/mar/07/

450th-birthdays-william-shakespeare-christopher-marlowe-andrew-dickson

poet USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/12/books/

james-a-emanuel-poet-who-wrote-of-racism-dies-at-92.html

author UK / USA

https://www.npr.org/2016/01/09/

462437823/as-writers-wages-wane-in-digital-chapter-authors-pen-demands

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/04/stephen-king-how-i-wrote-carrie-horror

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/09/elizabeth-jane-howard-interview

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/01/

arts/william-demby-novelist-and-reporter-dies-at-90.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/jun/06/ray-bradbury

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/21/books/21mcguane.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/29/books/29salinger.html

best-selling author USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/28/

books/rabbi-harold-s-kushner-dead.html

authorship UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/apr/23/

william-shakespeare-authorship-birthday

Martina Cole > Britain's bestselling author

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/oct/28/martina-cole-queen-of-crime

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/may/31/martina-cole-books

pen name USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/12/

arts/ellen-douglas-southern-novelist-dies-at-91.html

literary establishment

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/may/31/martina-cole-books

The Paris Review, American literary magazine

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/10/arts/10guinzburg.html

woman of letters USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/09/

books/09jenkins.html

literary greats > The Times obituaries

literary feuds UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/sep/04/

books.booksnews

literary fraud UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/sep/23/

books.booksnews

literary agent USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/07/

books/robert-lescher-literary-agent-is-dead-at-83.html

literary agent > Pat Kavanagh

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/oct/21/

publishing

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/oct/21/2

literary legend > Ray Bradbury

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/20/us/

20ventura.html

Ben Sonnenberg Jr. USA

1936-2010

founder of literary journal

Grand Street

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/26/

books/26sonnenberg.html

pioneering feminist author > Amber Reeves

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/apr/02/

featuresreviews.guardianreview33

novelist UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/16/

books/nettie-jones-fish-tales-reissued.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/

opinion/stephen-king-can-a-novelist-be-too-productive.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/jan/25/andrew-miller-interview

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/apr/19/james-frey-final-testament-bible

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/booknews/7867988/

Dame-Beryl-Bainbridge-75-dies-of-cancer.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/jun/24/

neil-gaiman-carnegie-graveyard-book

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/apr/15/

orangeprizeforfiction2008.orangeprizeforfiction

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/jul/19/

guardianobituaries.booksobituaries

postmodernist novelist

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/04/03/

1242508803/john-barth-novelist-author-obituary

satirical novelist

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/04/

books/david-bowman-author-of-let-the-dog-drive-dies-at-54.html

diarist UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/01/

travis-elboroughs-top-10-literary-diarists

writer

pulp writer

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/jul/19/

guardianobituaries.booksobituaries

mystery novelist / writer > Donald E. Westlake

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/02/

books/02westlake.html

UK > science fiction writer / author >

Arthur C.

Clarke 1917-2008

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/mar/19/

arthurcclarke

https://www.reuters.com/article/scienceNews/idUSCOL140932

20080319

https://www.reuters.com/article/scienceNews/idUKL18380679

20080319

online writer

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2006/apr/03/

news.newmedia1

ghost writer

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/feb/12/

roman-polanski-ghost-writer

travel writer > Patrick Leigh Fermor

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/mar/02/

news.travelbooks

philosophical and revolutionary writers

philosopher

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/may/19/

daniel-dennett-intuition-pumps-thinking-extract

thinkers and revolutionaries

thinker

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/may/19/

daniel-dennett-intuition-pumps-thinking-extract

storyteller

USA

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/apr/06/

realising-were-all-made-up-characters-in-a-story-world-

helps-me-understand-people

storyteller

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/20/

books/20frank.html

story

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/apr/06/

realising-were-all-made-up-characters-in-a-story-world-

helps-me-understand-people

story

USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/28/

salinger-stories-leaked-online/

Homo narrans, the

storytelling animal UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/apr/06/

realising-were-all-made-up-characters-in-a-story-world-

helps-me-understand-people

USA > the Beats: beat generation

UK / USA

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jul/04/

lawrence-ferlinghetti-interview-poets

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/24/

books/carolyn-cassady-beat-generation-writer-dies-at-90.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/06/

books/columbia-u-haunts-of-lucien-carr-and-the-beats.html

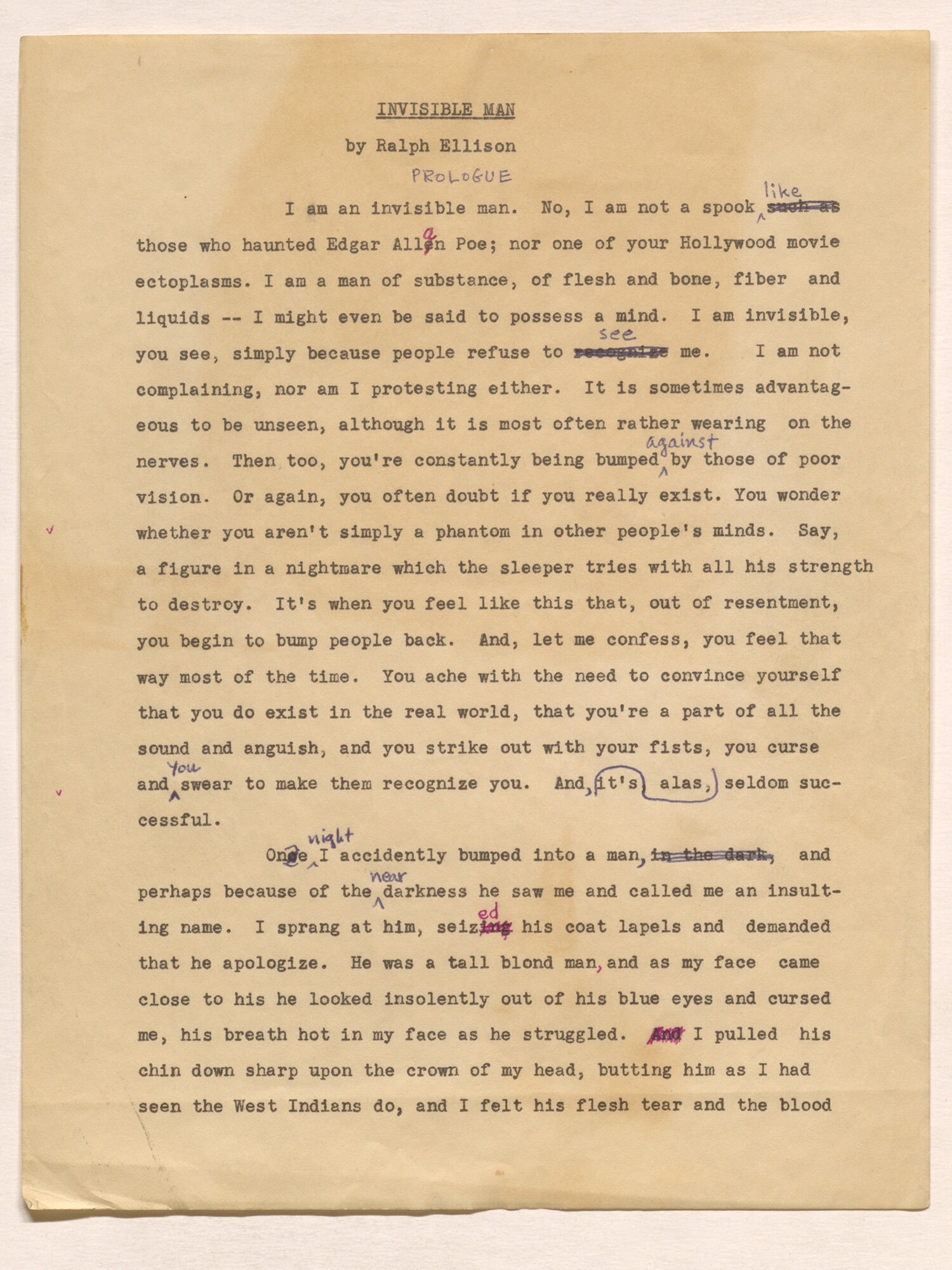

A draft of the prologue of “Invisible Man.”

Photograph: Ralph Ellison Papers,

Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of

Congress.

© The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust.

T BOOK CLUB

Surreal Encounters in Ralph Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man’

Breaking with the dominant literary styles among Black writers

at the time,

the author expanded the limits of realism to create a world

that was,

and remains, all too familiar.

NYT

June 3, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/

t-magazine/ralph-ellison-invisible-man.html

write

manuscript

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/22/

business/media/a-pearl-buck-novel-new-after-4-decades.html

draft

USA

https://www.npr.org/2023/04/30/

1171897684/toni-morrisons-diary-entries-early-drafts-and-letters-

are-on-display-at-princeto

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/

t-magazine/ralph-ellison-invisible-man.html

type

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/mar/02/

news.travelbooks

typewriter

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/

t-magazine/ralph-ellison-invisible-man.html

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/24/

tablets-romance-typewriters-underwood

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/08/nyregion/

manson-whitlock-typewriter-repairman-dies-at-96.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/may/02/

enid-blyton-exhibition-writer-imagination

http://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2011/may/11/

authors-typewriters-in-pictures

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2009/dec/01/

typewriters-fine-writing

https://www.loc.gov/folklife/lomax/alan/photos/08.html

Key workers:

writers at their typewriters - in

pictures UK 2011

Since Mark Twain became the first author

to submit a typed manuscript

with Life on the Mississippi in 1883,

authors have been devoted to their machines.

As manufacture of typewriters comes

to a close,

we look back on some of the iconic images of creators

at their keyboard

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/gallery/2011/may/11/

authors-typewriters-in-pictures

scribe

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/jul/20/

highereducation.books

NYC > Harlem Renaissance

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/15/

books/harlem-renaissance-novel-by-claude-mckay-is-discovered.html

literary competition

book prize

shortlist

be shortlisted

USA > The Pulitzer Prizes

UK

Honoring Excellence

in Journalism and the Arts

https://www.pulitzer.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Pulitzer_Prize

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/

frank-mccourt-author-of-angelas-ashes-dies-

1753207.html - 20 July 2009

Samuel Johnson prize

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

samueljohnsonprize

Booktrust teenage prize

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

booktrustteenageprize

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/nov/01/

gregory-hughes-booktrust-teenage-prize

Man Booker Prize USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

man-booker-prize

Man Booker Prize

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/15/

business/media/richard-flanagan-wins-man-booker-prize-

for-tale-of-world-war-ii-pow.html

Man Booker Prize

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/oct/16/

bookerprize2007.thebookerprize6

The Booker prize

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

booker-prize

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/sep/26/booker-prize-shortlist-breaks-sales-records

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2010/oct/12/howard-jacobson-the-finkler-question-booker

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/nov/02/books.india

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/oct/12/bookerprize2006.thebookerprize

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/oct/11/books.bookerprize2006

Booker prize

USA

2012

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/16/

hilary-mantel-wins-a-second-booker-prize/

Booker prize

2011 UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

booker-prize-2011

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/19/

books/julian-barnes-wins-the-man-booker-prize.html

The Booker shortlist UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/interactive/2011/oct/11/booker-prize-shortlist-2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/sep/26/booker-prize-shortlist-breaks-sales-records

the Blooker Prize UK

http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2006/apr/03/news.newmedia1

the Turner prize

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jul/05/arts.artsnews

PEN/Faulkner Award

USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/07/

atticus-lish-wins-penfaulkner-prize/

win the award

win the Booker

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/

booker-prize

the Big Gay Read

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/may/11/gayrights.books

the Whitbread Book of the Year

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/sep/26/childrensservices.books

the Romantic Novelists Association prize

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/apr/21/books.booksnews

the Carnegie medal

UK

http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/06/in_praise_of_the_carnegie_priz.html

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/may/05/film.cannes2006

the Samuel Johnson non-fiction prize

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/jul/15/

samueljohnsonprize.samueljohnsonprize2008

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jun/15/film.books

National Book Award

USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/10/04/

555536038/here-are-the-finalists-for-the-2017-national-book-awards

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/19/

books/19awards.html

Book Awards

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/15/us/

louise-erdrichs-novel-the-round-house-wins-national-book-award.html

translator

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/18/

william-weaver

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Books >

Writers, Awards

Salman Rushdie:

'Fiction saved my life'

Symbol, victim, blasphemer, target

– Salman Rushdie, it seems,

is anything

people need him to be.

As his new novel is published,

the writer talks to Boyd Tonkin

Friday, 11 April 2008

The Independent

In Salman Rushdie's tenth novel, the great Mughal emperor Akbar conjures up his

favourite wife by the sheer force of imagination alone: "The creation of real

life from a dream was a superhuman act, usurping the prerogative of the gods."

Non-existent, but still solid enough to breed fiery resentment from her rival

queens, Jodha in The Enchantress of Florence can stand for all the heretical

coups and stunts of story-telling magic that have peppered Rushdie's fiction for

the past 30 years. Yet this grand master of the power of fantasy has suffered as

its slave as well. More than any other writer alive, he has found himself

transformed into a character – ogre, joker, beast and, just occasionally, hero –

in other people's scripts and stories.

"Sometimes," he says, his voice tinged more by sadness than anger, "I think that

when people become famous, there's a public perception that they are not human

beings any more. They don't have feelings; they don't get hurt; you can act and

say as you like about them." They become "things, not people" – a status and a

plight that, outside global politics and showbiz, Rushdie has sampled at a

length and depth unparalleled in modern times.

Even if you try hard to treat the novelist as a professional author, not a

symbol, a slogan or a cause, the buzz of fantasy kicks in. My particular Rushdie

delusion endows him with the Jodha-like ability to materialise out of thin air.

At a Booker Prize dinner in the mid-1990s, with the Iranian fatwa that followed

The Satanic Verses in 1989 still a clear and present danger to his life, the

shifty-eyed ox in a tux seated next to me promptly vanished as the first course

arrived. The next time I turned my head, the target of several deadly serious

assassination plots (and Ayatollah Khomeini's judgement, remember, was suspended

but not rescinded by Tehran in 1998) had slipped in to replace his ever-watchful

bodyguard. Not long ago, I went to dinner at a friend's, looked away to grab a

crisp – and, abracadabra, there he suddenly sat.

Now, I push through an open door at his agent's eerily silent offices, wander

into a seemingly deserted room – and find him standing alone, near a shelf of

books by another quizzically subversive spellbinder, and one of his true heroes:

Italo Calvino.

Everyone, fan or foe, invokes their own imaginary Rushdie. We dream him up, and

he duly takes shape: as blaspheming apostate for many still-outraged Muslims; as

cocky subcontinental pseud for old-school British racists; as martyr to free

speech for liberal literati. With the announcement of his knighthood, last June,

this parade of straw men swelled to a seething carnival of prejudice and

projection. From one corner, the pious haters swung into action: the parliament

of Pakistan passed a motion against the honour as an insult to Islam. From

another, the gossip-sheet haters seized on rumours of an impending divorce to

renew their attritional campaign of "attacks on my physical appearance, as if

I've ever invested anything in how beautiful I am". From yet another, the

kneejerk-leftist haters matched them all in bile: The Guardian ran a defamatory

rant from a Cambridge English don that grossly misrepresented his books, his

politics and his ideas with a recklessness that would shame a GCSE-level duffer.

"Truthfully, I don't get it," says this hard-working 60-year-old writer, clad in

a writer's comfy sweater, mulling over his burdensome double life as

multipurpose scapegoat. "I just don't understand it. I think I've led a serious

creative life. All that I've tried to do for over 30 years is to be the best

writer that I know how to be... It's as if people don't see that in some way,

and that's distressing."

The flesh-and-blood author has never wanted to make a mystery of himself. Even

in the perilous depths of the fatwa, he proved easier to contact than many shy

sages with no price upon their heads. Now, he is about to launch the fourth

season of the World Voices festival in New York: a crowd-pulling array of global

authors that Rushdie has energetically fronted and boosted from the start. With

his friends Umberto Eco and Mario Vargas Llosa, he will re-stage the "Three

Musketeers" gig that proved so popular in the 1990s. And, for a month every

year, he makes time to teach modern fiction (including such colleagues and

contemporaries as Angela Carter, Kazuo Ishiguro and Hanif Kureishi) at Emory

University in Georgia: "There's something very enjoyable about sitting in a room

with 16 intelligent young people, talking about a book."

So ordinary life, and ordinary talk, carries on regardless. The Indian-origin

family who run a gas station he uses in New York were "thrilled and proud" at

the knighthood. Most people have responded "very sweetly" to it, he says: they

understand "that real life is not the same thing as what's in the newspapers. If

you know that, it's a way of dealing with what appears in print." Still, he

admits: "I don't get over it. It hurts me and, like anybody else who gets hurt,

you have to try to heal."

So is work a good way to heal? "Yes. Last year was a horrible year for me in

many ways because of the end of my marriage" – his fourth, to the model, actress

and TV presenter Padma Lakshmi – "and I don't know how I got inside this book,

really." Hard on the heels of the knighthood furore, reports of their split

brought another media shot of the sour cocktail of mockery and malice that had

greeted the start of the couple's relationship. "It wasn't straightforward" to

plunge into the therapeutic toil of fiction, he says, "considering the enormous

amount of upheaval. But I do think it saved my life, this book. It reminded me

of who I've always wanted to be, and who I think I am. And it was a matter of

enormous pride to be able to do it and, at the end, to think, 'Not so bad.'"

The Enchantress of Florence returns Rushdie to the roots of his craft, and his

gift. From Midnight's Children in 1981 to Shalimar the Clown in 2005, his

strongest fiction has explored and enacted the interchange of history, memory

and myth – as comedy, as tragedy, and often as a brand of fantasy that dances

with, and through, recorded facts. The new novel sticks to two connected sectors

of the past: the early 1500s in Florence, and the later 16th century in the new

(but soon to be abandoned) Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri. So India and Italy

embrace in a tale of two cities.

The book teases out the strands that bind two types of Renaissance, two types of

humanism, and two types of magic. Via Rushdie's narrative alchemy, one woman,

the "hidden princess" Qara Köz, knits the entire plot in her westward drift from

court to court across (and beyond) the known world. Driven by the

Hitchcock-style V C "McGuffin" of a blond stranger in Akbar's city and his tall

tales of a genealogy that weds East and West, the story unspools irresistibly

like a roll of brightly coloured ribbon, full of the virtues of "lightness and

swiftness" that Calvino taught, and Rushdie admires. "I just had the most good

time writing it," the author purrs, "and it's slightly given me the appetite for

doing it again."

"For me," he says, "one of the most interesting discoveries of this book was how

similar the two worlds were. In my starting-point idea," which drew on the

Indian princess who plays a leading role in Ariosto's Renaissance epic poem

Orlando Furioso, "I thought, 'Here are these two worlds that have very little

contact with each other, and yet are both at a kind of peak.' But the more I

found out about it, the more I found that, actually, they were surprisingly

alike: in the interest in magic, in the remarkable hedonism of both worlds – the

very open debauchery of both cultures." "Florence was everywhere and everywhere

was Florence," thinks the Tuscan scamp turned Ottoman warlord Argalia, one of

the novel's self-seeking bridge-builders and go-betweens who bind East and West.

Rushdie says that "how the world adds up, and how this part connects to that

part, is something I've been trying to explore for a really long time now. The

Satanic Verses is a novel about migrations, but in the last three or four books,

I've been trying to write about how over here connects to over there." He adds:

"I'm not trying to say they're identical, but human nature is identical. It's

interesting to see that human beings were everywhere alike... I'm not a

relativist. I do think that there is such a thing as human nature, and that the

things that we have in common are perhaps greater than the things that divide

us."

So the arch-Florentine Niccolo Machiavelli (whom Rushdie commends as "a profound

philosopher of republican humanism") seeks for the "hidden truths" about society

and politics behind the official smokescreen of doctrine and dignity. Two

generations later, in Fatehpur Sikri, the Emperor Akbar slips slowly away from

mainstream Islam to harbour dreams of a synthetic, humanistic faith with "man at

the centre of things, not God".

All of this actually happened. I have visited the riotously carved pavilion in

the ghost city of Fatehpur Sikri ("a most enchanted place," says Rushdie), where

the questing, tolerant Akbar welcomed spokesmen for different creeds to debate

the nature of God, and man, in a mood of mutual goodwill and respect. For

Rushdie, "I myself don't think that Akbar ever really moved outside Islam...

However much he experimented with all these ideas, I don't think he ever ceased

to be a believing Muslim. But he had this pantheistic idea: that, in the end,

all religions are one."

The author stresses that he deals in historical fiction, not topical allegory or

coded polemic. "When I'm writing a book, sentence by sentence, I'm not thinking

theoretically. I'm just trying to work out the story from inside the characters

I've got." His novel may feature a prince who hopes that "in Paradise, the words

'worship' and 'argument' mean the same thing", but he has no particular message

for believers, or unbelievers, today. "My impulse was not didactic. It was the

novelist's impulse: to bring things to life in an interesting way. I don't like

books that seem to want to teach me things. Which is not to say that one doesn't

learn from books – but you do your own learning in your own way."

Rushdie did plenty of new learning for The Enchantress of Florence ("I've never

done so much research in my life") and he slips in a seven-page bibliography.

During a rough passage, history offered both an escape and a homecoming. "It

felt like returning to a use of my mind, a place where I hadn't been for a long

time," says the history graduate of King's College, Cambridge. He remembers that

a favourite tutor there, Arthur Hibbert, told him that "you should not write

history until you can hear the people speak. I've always thought that was quite

a good piece of advice for fiction, too. For me, this book was that act: trying

to understand the people well enough so that I could hear them speak."

These princes, whores, scholars and warriors, Rushdie insists, live in their own

times, on their own terms. He worries that the gossip-hounds invariably treat

his fiction as "disguised autobiography". In this yarn of a glamorous incomer

from India who seduces Italy, many will seek for echoes of his former wife, once

a prime-time host on Italian television. But Qara Köz cannot be Padma Lakshmi:

"No – she's 400 years older!" More seriously: "The reason why none of these

characters can be equated to modern characters is that their processes of

thought are not modern. They don't make choices or understand the world in the

way that people in our day would. They are genuinely, I hope, of their time."

Like people in our time, though, they voyage across the world in search of

fortune, passion or adventure. Born in Bombay to a Kashmiri Muslim family; a

schoolboy at Rugby, a student at Cambridge; the 1980s superstar of a fresh,

border-hopping brand of cosmopolitan English-language fiction; then, after the

fatwa, the fugitive proof of the downside of fame before he came to rest in

Manhattan: Rushdie could hardly dodge migration and cultural mingling as a

recurrent motif in his work.

Yet, he thinks, the art of passing frontiers feels harder now. "Because of the

kind of life I've had, of being bounced around the planet quite a lot... I've

had constantly to be aware of likeness and unlikeness. And so it becomes a

subject for me." However, compared to 20 years ago, "the world has changed in

that people are more troubled" about human flux and flow. It used to be "easier

to imagine mass migration as a positive force, a liberating force, both for the

migrant and the culture into which the migrant came... Now, I think there are

big question marks around that idea because people are scared. The element of

fear has arrived in a way that wasn't there before, because of the violence of

the age."

In such a climate, the pleasures of story-telling rather than punditry beckon.

"Because of all the things that happened to me, there are people who think of me

primarily as some kind of political animal. I began to feel it was getting in

the way of people being able to read my books as books should be read." So

Rushdie won't be drawn far into the electoral drama unfolding in his adopted

home. "If I had a vote, I'd probably vote for Obama. But one of the things I've

been doing in America is: keeping out of it. It struck me that if an American

writer living in England began to start sounding off about who we should vote

for, people wouldn't take kindly to it. There was that long period when Roth was

living here. If Philip had started sounding off about whether you should vote

for Margaret Thatcher, it wouldn't have gone down well."

Back in his Renaissance, East and West, the power-plays of the past bewitch him

now, however fantastic they feel. "A lot of the stuff people might think is most

obviously made up is true," he says of The Enchantress of Florence, where we

meet not only Akbar and Machiavelli, but a bloodier icon. "The Ottoman campaign

against Dracula actually took place. Dracula's decision to impale 20,000 people

on stakes to put off the Ottoman army really happened. That's not magic realism,

although it sounds like it... It comes from the memoirs of a Serbian janissary

who took part in that campaign. There it is, gruesomely described in great

detail. I couldn't believe my luck when Dracula showed up."

In the minds of his diehard antagonists, Rushdie often figures as a near-demonic

blend of Dracula and the mythical (if not historical) Machiavelli. Yet he writes

and acts much more like his benevolent but baffled Akbar, showing through the

story-teller's unarmed might that "human nature, not divine will, was the great

force that moved history"; and hoping that "discord, difference, disobedience"

might turn out after all to be "wellsprings of the good".

Though enemies will continue to sharpen their stakes for him, the writer has

found his way back into a not-so-secret garden of fictional delights. With The

Enchantress of Florence, "there was an unexpected joy in the writing for me. I

loved doing it, and I felt that there is some sense of release into literature

in the book. It was a lot of fun, at a time that wasn't fun."

'The Enchantress of Florence' is published by Jonathan Cape (£18.99). Salman

Rushdie appears in International PEN's Free the Word! festival, Queen Elizabeth

Hall, London SE1, on Sunday at 7.30pm

Salman Rushdie: 'Fiction

saved my life',

I,

11 April 2008,

https://www.independent.co.uk/

arts-entertainment/books/features/

salman-rushdie-fiction-saved-my-life-807501.html

Harry Potter First Edition Auctioned

October 26, 2007

Filed at 11:27 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

LONDON (AP) -- A copy of J.K. Rowling's first Harry Potter novel sold at

auction Thursday for almost $41,000.

The copy of the hardback first edition of ''Harry Potter and the Philosopher's

Stone,'' published in 1997 and signed ''Joanne Rowling'' on the back of the

title page, was sold to an anonymous private bidder for $40,326 at Christie's

auction house.

At a London auction in May, a copy of ''Philosopher's Stone'' inscribed with a

personal dedication to the owner sold for more than $55,000, including buyer's

premium.

The book was published by Bloomsbury PLC with an initial print run of about 500

copies. Many were purchased by libraries, making copies in good condition

extremely rare.

It was published in the United States in 1998 as ''Harry Potter and the

Sorcerer's Stone,'' and the boy wizard soon became a publishing phenomenon.

The seventh and final installment in Harry's adventures, ''Harry Potter and the

Deathly Hallows,'' was published in July. The seven books have sold nearly 400

million copies and have been translated into 64 languages.

Harry Potter First

Edition Auctioned, NYT, 26.10.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/AP-

Books-Potter-Auction.html - broken link

J.K. Rowling Outs Hogwarts Character

October 20, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 12:37 a.m. ET

The New York Times

NEW YORK (AP) -- Harry Potter fans, the rumors are true: Albus Dumbledore,

master wizard and Headmaster of Hogwarts, is gay. J.K. Rowling, author of the

mega-selling fantasy series that ended last summer, outed the beloved character

Friday night while appearing before a full house at Carnegie Hall.

After reading briefly from the final book, ''Harry Potter and the Deathly

Hallows,'' she took questions from audience members.

She was asked by one young fan whether Dumbledore finds ''true love.''

''Dumbledore is gay,'' the author responded to gasps and applause.

She then explained that Dumbledore was smitten with rival Gellert Grindelwald,

whom he defeated long ago in a battle between good and bad wizards. ''Falling in

love can blind us to an extent,'' Rowling said of Dumbledore's feelings, adding

that Dumbledore was ''horribly, terribly let down.''

Dumbledore's love, she observed, was his ''great tragedy.''

''Oh, my god,'' Rowling concluded with a laugh, ''the fan fiction.''

Potter readers on fan sites and elsewhere on the Internet have speculated on the

sexuality of Dumbledore, noting that he has no close relationship with women and

a mysterious, troubled past. And explicit scenes with Dumbledore already have

appeared in fan fiction.

Rowling told the audience that while working on the planned sixth Potter film,

''Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince,'' she spotted a reference in the

script to a girl who once was of interest to Dumbledore. A note was duly passed

to director David Yates, revealing the truth about her character.

Rowling, finishing a brief ''Open Book Tour'' of the United States, her first

tour here since 2000, also said that she regarded her Potter books as a

''prolonged argument for tolerance'' and urged her fans to ''question

authority.''

Not everyone likes her work, Rowling said, likely referring to Christian groups

that have alleged the books promote witchcraft. Her news about Dumbledore, she

said, will give them one more reason.

J.K. Rowling Outs

Hogwarts Character,

NYT, 20.10.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/

AP-Books-Harry-Potter.html

J.K. Rowling Gives Rare U.S. Reading

October 16, 2007

Filed at 3:55 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

LOS ANGELES (AP) -- Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling made a rare U.S.

appearance, reading at the Kodak Theater in Hollywood in front of scores of

wand-clutching would-be wizards and witches.

Seated on a gold throne with plush red cushions, Rowling read Monday from the

seventh and final of her novels on Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry,

''Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.''

She then took a dozen preselected questions from the dressed-up and dazzled kids

and teens.

To accommodate a crushing demand for tickets for her first American appearance

since 2000, Rowling's American publisher sent a ''sorting hat'' like those used

to divide students into houses in the novels to 40 randomly selected Los Angeles

schools. Forty students from each school were then selected from the hat.

Rowling said the gimmick was meant to avoid the sort of madness she faced in her

last U.S. appearance seven years ago.

''Things had gotten a little unmanageable signing-wise in the terms of the

numbers who were turning up,'' she said, ''but I really missed being able to

interact directly with readers.''

All 1,600 students received a signed copy of ''Deathly Hallows.''

Rowling, a former schoolteacher, took the stage to a thundering, shrieking

ovation, then said: ''It wasn't like this when I was a teacher. If it had been,

I might never have left.''

When inevitably asked what she might be writing next, Rowling said only that it

would not be another supernatural epic.

''I think probably I've done my fantasy,'' she said. ''I think because Harry's

world was so large and detailed and I've known it so well and I've lived in it

for 17 years, it would be incredibly difficult to go out and create another

world.''

The reading was part of a weeklong visit by Rowling to the states known as the

''Open Book Tour.''

She also makes stops in New Orleans on Thursday and at New York's Carnegie Hall

on Friday.

J.K. Rowling Gives Rare

U.S. Reading, NYT, 16.10.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/AP-People-JK-Rowling.html

Doris Lessing

Wins Nobel Prize in Literature

October 11, 2007

The New York Times

By MOTOKO RICH

and SARAH LYALL

Doris Lessing, the Persian-born, Rhodesian-raised and London-residing

novelist whose deeply autobiographical writing has swept across continents and

reflects her engagement with the social and political issues of her time, today

won the 2007 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Announcing the award in Stockholm, the Swedish Academy described her as “that

epicist of the female experience, who with skepticism, fire and visionary power

has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny.” The award comes with an

honorarium of 10 million Swedish crown, about $1.6 million.

Ms. Lessing, who turns 88 later this month, never finished high school and

largely educated herself through her voracious reading. She was born in 1919 to

British parents in what is now Iran, raised in colonial Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

and currently resides in London. She has written dozens of books of fiction, as

well as plays, non-fiction and two volumes of her autobiography. She is the 11th

woman to win a Nobel Prize in literature.

Ms. Lessing learned of the news from a group of reporters camped on her doorstep

as she returned from visiting her son in the hospital. “I was a bit surprised

because I had forgotten about it actually,” she said. “My name has been on the

short list for such a long time.”

With the sound of a phone ringing persistently from inside her house, Ms.

Lessing said that on second thought, she was not as surprised, “because this has

been going on for something like 40 years,” referring to previous times she has

been on the short list for the Nobel. “Either they were going to give it to me

sometime before I popped off or not at all.”

Stout, sharp and a bit hard of hearing, Ms. Lessing excused herself after a few

moments to go inside. “Now I’m going to go in to answer my telephone,” she said.

“I swear I’m going upstairs to find some suitable sentences which I will be

using from now on.”

Although Ms. Lessing is passionate about social and political issues, she is

unlikely to be as controversial as the previous two winners, Orhan Pamuk of

Turkey and Harold Pinter of Britain, whose views on current political situations

led commentators to suspect that the Swedish Academy was choosing its winners in

part for nonliterary reasons.

Ms. Lessing’s strongest legacy may be that she inspired a generation of

feminists with her breakthrough novel, “The Golden Notebook.” In its citation,

the Swedish Academy said: “The burgeoning feminist movement saw it as a

pioneering work and it belongs to the handful of books that informed the 20th

century view of the male-female relationship.”

Ms. Lessing wrote candidly about the inner lives of women and rejected the

notion that they should abandon their own lives to marriage and children. “The

Golden Notebook,” published in 1962, tracked the story of Anna Wulf, a woman who

wanted to live freely and was in some ways Ms. Lessing’s alter-ego.

Because she frankly depicted female anger and aggression, she was attacked as

“unfeminine.” In response, Ms. Lessing wrote: “Apparently what many women were

thinking, feeling, experiencing came as a great surprise.”

Although she has been held up as an early feminist icon, Ms. Lessing later

denied that she herself was a feminist, earning the ire of some British critics

and academics.

Clare Hanson, professor of 20th century literature at the University of

Southampton in Britain and a keynote speaker at the second international Doris

Lessing Conference this past July, said: “She’s been ahead of her time,

prescient and thoughtful, immensely wide-ranging.”

Ms. Lessing debuted with the novel “The Grass is Singing” in 1950, chronicling

the relationship between a white farmer’s wife and her black servant. In her

earliest work, Ms. Lessing drew upon her childhood experiences in colonial

Rhodesia to write about the clash of white and African cultures and racial

injustice.

Because of her outspoken views, the governments of both Southern Rhodesia and

South Africa declared her a “prohibited alien” in 1956.

Ms. Lessing was born Doris May Tayler in 1919 in what was then known as Persia

(now Iran). Her father was a bank clerk and her mother was trained as a nurse.

Lured by the promise of farming riches, the family moved to Rhodesia, where Ms.

Lessing had what she has described as a “painful” childhood.

She left home when she was 15. In 1937 she moved to Salisbury (now Harare) in

Southern Rhodesia, where she took jobs as a telephone operator and nursemaid. At

19, she married and had two children. A few years later, she felt trapped, and

abandoned her family. She later married Gottfried Lessing, a central member of

the Left Book Club, a left wing organization, and they had a son together.

Ms. Lessing, who briefly joined the Communist Party, later repudiated Marxist

theory and was criticized for doing so by some British academics.

She divorced Mr. Lessing and she and her young son moved to London, where she

began her literary career in earnest. When “The Golden Notebook” was first

published in the United States, Ms. Lessing was still unknown. Robert Gottlieb,

then her editor at Simon & Schuster and later at Knopf, said that it garnered

“extremely interesting reviews” but sold only 6,000 copies. “But they were the

right 6,000 copies,” Mr. Gottlieb said by telephone from his home in New York.

“The people who read it were galvanized by it and it made her a famous writer in

America.”

Speaking from Frankfurt during the annual international book fair, Jane

Friedman, president and chief executive of HarperCollins, which has published

Ms. Lessing in the U.S. and the United Kingdom for the last 20 years, said that

“for women and for literature, Doris Lessing is a mother to us all.”

Ms. Lessing’s other novels include “The Good Terrorist,” “Martha Quest,” and

“Love Again.” Her latest novel is “The Cleft,” published by HarperCollins in

July.

In a review of “Under My Skin,” the first volume of Ms. Lessing’s autobiography,

Janet Burroway, writing in The New York Times Book Review, said: “Mrs. Lessing

is a writer for whom the idea that ‘the personal is the political’ is neither

sterile nor strident; for her, it is an integrated vision.”

On her doorstep, Ms. Lessing said she was still writing, “but with difficulty

because I have so little time,” referring to the regular visits she is making to

the hospital to visit her son.

Motoko Rich reported from Frankfurt

and Sarah Lyall from London.

Doris Lessing Wins Nobel

Prize in Literature, NYT, 11.10.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/11/world/11cnd-nobel.html

Harry Potter Author

Talks About Ending

July 26, 2007

Filed at 10:43 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

NEW YORK (AP) -- Less than a week after the release of the final Harry Potter

book, author J.K. Rowling is giving hints about its conclusion.

Before publication, Rowling pleaded for secrecy about the ending of ''Harry

Potter and the Deathly Hallows.'' But in an interview broadcast Thursday on

NBC's ''Today'' show and in one published Thursday in USA Today, she discussed

Harry's fate.

THOSE WHO DO NOT WANT TO KNOW HOW IT ALL TURNS OUT FOR THE BOY WIZARD SHOULD

STOP READING HERE.

''I'm very proud of the fact that as we went into this book, many, many readers

believed it was a real possibility that Harry would die. That's what I was

aiming for,'' she said on NBC.

In the book, Voldemort meets his end and Harry lives. But Rowling said Harry's

survival was not always a certainty.

''In the early days, everything was up for grabs,'' she told USA Today. ''But

early on I knew I wanted Harry to believe he was walking toward his death, but

would survive.''

The last volume of Rowling's fantasy series, ''Harry Potter and the Deathly

Hallows,'' was released Saturday to international fanfare as millions read to

find out whether Harry lived or died. More than 10 million copies sold over the

weekend.

In a prerelease interview with The Associated Press, Rowling acknowledged that

she had no control over discussions about the book once it went on sale. But she

said that she hoped readers would finish the book to find out what happens,

rather than to peek at the ending.

''It's like someone coming to dinner, just opening the fridge and eating

pudding, while you're standing there still working on the starter. It's not

on,'' she said.

She also told the AP that after finishing the last book, she ''felt terrible for

a week.''

''It was like a bereavement, even though I was pleased with the book. And then

after a week that cloud lifted and I felt quite lighthearted, quite liberated,''

she said.

''It was this amazing cathartic moment -- the end of 17 years' work,'' she told

NBC.

When asked if she felt like she had to say goodbye to Harry, she said, ''Yes and

no. He'll always be a presence in my life, really.''

She acknowledged that the final Potter installment leaves some loose ends.

''It would have been humanly impossible to answer every single question that

comes up,'' she told NBC. ''Because, I'm dealing with a level of obsession in

some of my fans that will not rest until they know the middle names of Harry's

great, great grandparents.''

Rowling, whose seven Potter books have sold more than 335 million copies

worldwide, said she plans to take time off to be with her family and will

continue writing. She told USA Today she has two writing projects -- one for

children and one for adults.

But whether she will write about her young wizard again, she said: ''I think

I've kind of done the wizarding world. ... I have done my Harry Potter.''

Harry Potter Author

Talks About Ending, NYT, 26.7.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/AP-Harry-Potter-Rowling.html

Harry Potter

and the man who conjured up

Rowling's millions

As the last Hogwarts book appears,

the author's multi-millionaire

agent

will stay in the shadows

Sunday July 15, 2007

David Smith

The Observer

When midnight strikes on Saturday, there will be no missing the star of the

show. JK Rowling, the world's most successful author, will be the centre of

attention for 1,700 children at London's Natural History Museum as she signs

copies of the seventh and final Harry Potter adventure.

Throughout the canny construction of 'Brand Potter' - books, films, video

games, and now even stamps - one figure has been ever present, like a shadow

glimpsed in the cloisters of Hogwarts school.

This enigmatic but utterly crucial influence is Christopher Little, literary

agent, fierce protector of Rowling and, thanks to the boy wizard, now a

millionaire many times over.

Little has masterminded Rowling's career, from the moment he spotted the

potential of her first manuscript to this week's publication of Harry Potter and

the Deathly Hallows, which guarantees him yet another jackpot. Amazon, the

online retailer, has already sold a record 1.8 million advance copies.

Rowling's publisher, Bloomsbury, held a ballot for the launch at the Natural

History Museum, which drew applications from 90,000 children. The first 500

names out of the hat will hear Rowling read from the new book at midnight -

webcast live around the world - while a further 1,200 will receive signed

copies. Simultaneously, 279 branches of Waterstone's will open their doors, and

there will be numerous other launch parties at independent bookshops up and down

the country. This week the Royal Mail is issuing a commemorative set of Harry

Potter stamps.

Little, a 65-year-old grandfather, has been content to remain behind the scenes,

rarely speaking in public and seldom photographed. But when he first signed up

Rowling, he reportedly struck a deal under his usual terms: 15 per cent of gross

earnings for the UK market and 20 per cent for merchandising rights, for film,

for the US market and for translation deals. With the author's fortune now

standing at more than £540m, Little's return has to be estimated as at least

£50m.

'He was the luckiest agent ever - when something like that falls in your lap it

is luck, but he made the most of it,' said Ed Victor, a leading literary agent.

'He has run the brand admirably. He had to build up an organisation to defend

and promote and advance his author's rights and it's all been done very

tastefully. He's a charming and affable fellow, but made of steel underneath.'

The son of a coroner who served as a First World War fighter pilot, Little grew

up in Liversedge, West Yorkshire, and gained five O-levels at Queen Elizabeth

Grammar School in Wakefield, only to leave during the sixth form to join his

uncle's textile business in 1958. The fledgling entrepreneur had impressed his

headteacher, EJ Baggaley, who wrote: 'My impression is that he is well suited

for a business career - sales management, for instance.'

He spent most of the Sixties and Seventies in the shipping industry in Hong Kong

before returning to London to set up a recruitment consultancy called City Boys.

His switch to the literary world happened by accident in 1979. A schoolfriend

and fellow Hong Kong trader, Philip Nicholson, had written a thriller and was

seeking representation. Little agreed to take him on and the book, Man on Fire,

was published under the pseudonym AJ Quinnell. It went on to sell 7.5 million

copies worldwide and become a Hollywood film.

In his only press interview, in 2003, Little recalled: 'The literary agency was

really a hobby which started through an accident. I was helping an old friend in

his writing career. I had been running as a full-time business for about six

years when Harry Potter arrived.'

The agency, run in 'cramped' and 'near-Dickensian' offices in Fulham, south-west

London, was cash-strapped until touched by Potter's magic wand. Literary

folklore has it that Rowling, then a penniless 29-year-old single mother, walked

into a public library in Edinburgh, looked up a list of literary agents and

settled on the name Christopher Little because it sounded like a character from

a children's book.

Bryony Evens, his office manager at the time, has said that it went straight

into the reject basket because 'Christopher felt that children's books did not

make money'. But its unusual black binding caught her eye, prompting her to read

the synopsis and show it to Little. He recalled: 'I wrote back to JK Rowling

within four days of receiving the manuscript. I thought there was something

really special there, although we could never have guessed what would happen to

it.' He managed to sell it to Bloomsbury for £2,500, but later reaped huge

rewards from international rights and has won a reputation as a brilliant

deal-maker who puts Rowling first.

According to those who know him, the 6ft 3in Little, divorced with two sons, is

unchanged by his wealth and a breed apart from the flamboyant agents and

literati who frequent West End restaurants. But he reportedly spent £250,000 on

his 60th birthday party at the Chelsea Physic Garden and has admitted: 'I do

love sailing, but I rent the boats when I want them - it does save a lot of

hassle.'

Ian Chapman, chief executive of Simon & Schuster and a friend of Little for 20

years, said: 'He's very Yorkshire, very northern, very honest and ... still the

same simple fellow he's always been.'

The Deathly Hallows: a sneak preview In a trailer for the forthcoming ITV

documentary, A Year in the Life... J K Rowling, the camera lingers long enough

on a printed manuscript of the novel, dated 23 October 2006, to make the opening

visible to the eagle eyed. It reads:

'Chapter One. The Dark Lord Ascending. The two men appeared out of nowhere, a

few yards apart in the narrow, moonlit lane. For a second they stood quite

still, wands pointing at each other's chests: then, recognising each other, they

stowed their wands beneath their cloaks and set off, side by side, in the same

direction.

"News?", asked the taller of the two.

"The best," replied Snape.'

Harry in numbers

5 seconds between each pre-order on Amazon website - 1.8 million in total.

279 branches of the book chain Waterstone's holding launch parties at the stroke

of midnight on Saturday.

2,000 people expected in the queue at Waterstone's on Piccadilly, London.

24 hours and 1 minute: running time for the audio edition.

90 countries in which the book is being published.

7/4 odds from Ladbrokes on Harry Potter committing suicide at the end of Harry

Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

Harry Potter and the man

who conjured up Rowling's millions,

O,

15.7.2007,

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/jul/15/

harrypotter.books

Iran Cleric:

Rushdie Fatwa Still Stands

June 22, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 11:18 a.m. ET

The New York Times

TEHRAN, Iran (AP) -- An high-level Iranian cleric said Friday that the

religious edict calling for the killing of Salman Rushdie cannot be revoked, and

he warned Britain was defying the Islamic world by granting the author

knighthood.

Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami reminded worshippers of the 1989 fatwa during a sermon

at Tehran University, aired live on state radio. Thousands of worshippers

chanted ''Death to the English.''

Khatami does not hold a government position but has the influential post of

delivering the sermon during Friday prayers once a month in the Iranian capital.

He did not directly call for the fatwa to be carried out.

''Awarding him means confronting 1.5 billion Muslims around the world,'' Khatami

said. ''In Islamic Iran, the revolutionary fatwa ... is still alive and cannot

be changed.''

Then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued the fatwa in 1989,

calling on Muslims to kill Rushdie because his book ''The Satanic Verses'' was

deemed insulting to Islam. Rushdie was forced into hiding for a decade, and the

edict deeply damaged Britain's relations with Iran. In 1998, the Iranian

government sought to patch up ties by declaring that it would not support the

fatwa but that it could not be rescinded.

Queen Elizabeth II's decision to knight Rushdie drew a complaint from the

Iranian government and protests around the Muslim world.

About 2,000 people rallied in several Pakistani cities on Friday, calling for

Rushdie to be killed and for a boycott of trade with Britain.

A leader of Pakistan's Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam party compared Rushdie's award to

the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad published last year in a Danish newspaper,

which provoked protests and rioting in Muslim countries.

''Earlier they had published cartoons of our Prophet, and now they have given an

award to someone who deserves to be killed,'' Abdul Ghafoor Hayderi told a crowd

of about 1,000 people in Karachi, Pakistan's largest city.

Pakistan is a close ally of the United States and Britain in the war on terror,

but it has condemned Rushdie's knighthood.

In India's Muslim-majority Kashmir region, a strike over Rushdie's honor closed

most shops, offices and schools in the summer capital, Srinagar.

Mufti Mohammad Bashir-ud-din, head of Kashmir's Islamic court, said Rushdie was

''liable to be killed for rendering the gravest injury to the sentiments of the

Muslims across the world.''

Britain has defended its decision to honor Rushdie, one of the most prominent

novelists of the late 20th century. His 13 books have won numerous awards,

including the Booker Prize for ''Midnight's Children'' in 1981.

Muslims angered by Britain's decision protested in London on Friday.

''Rushdie is a hate figure across the Muslim world because of his insults to

Islam,'' said Anjem Choudray, protest organizer. ''This honor will have

ramifications here and across the world.''

The award, announced Saturday, was among the Queen Elizabeth II's Birthday

Honors list, which is decided on by independent committees who vet nominations

from the public and government.

Some analysts have expressed surprise his award was approved.

''There is an impression they really didn't consider the potential reaction,''

said Rosemary Hollis, director of research at London's Chatham House think tank.

''But there is a sense that showing too much sensitivity is to kowtow to

radicals.''

Associated Press writers David Stringer in London

and Aijaz Hussain in

Srinagar, India,

contributed to this story.

Iran Cleric: Rushdie

Fatwa Still Stands, NYT, 22.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/world/AP-Rushdie-Protests.html

Secret of Horror Writer's

Lineage Broken

March 17, 2007

Filed at 1:58 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

PORTSMOUTH, N.H. (AP) -- Joe Hill knew it was only a matter of time before

one of the publishing industry's hottest little secrets became common knowledge.

He just wished he could have kept it under wraps a bit longer.

But when Hill's fantasy-tinged thriller, ''Heart-Shaped Box,'' came out last

month, it was inevitable that his thoroughbred blood lines as a writer of horror

and the supernatural would be out there for all to see.

After 10 years of writing short stories and an unpublished novel under his pen

name, Hill knows that the world is now viewing him through a different prism --

as the older son of Stephen King.

Hill, 34, took on his secret identity to test his writing skills and

marketability without having to trade on the family name.

''I really wanted to allow myself to rise and fall on my own merits,'' he said

over breakfast in this coastal city. ''One of the good things about it was that

it let me make my mistakes in private.''

The moniker he chose did not come out of the blue. He is legally Joseph

Hillstrom King, named for the labor organizer whose 1915 execution for murder in

Utah inspired the song, ''Joe Hill,'' an anthem of the labor movement. His

parents, who came of age during the 1960s, ''were both pretty feisty liberals

and looked at Joe Hill as a heroic figure,'' he said.

''Heart-Shaped Box,'' a title drawn from a song by the rock group Nirvana, is a

fast-paced tale of another man with dual identities. Judas Coyne, born Justin

Cowzynski, is an over-the- hill heavy metal rocker with a strange hobby:

amassing ghoulish artifacts.

When Coyne learns that a suit purportedly haunted by a ghost is up for grabs on

an online auction site, he can't resist adding it to his creepy collection.

Things turn ugly fast after Coyne learns that the suit's occupant is a spooky

spiritualist bent on vengeance following the death of his stepdaughter.

The book has drawn good reviews, with The New York Times' Janet Maslin calling

it ''a wild, mesmerizing, perversely witty tale of horror'' that is ''so

visually intense that its energy never flags.'' And with its cinematic, and

bloody, ending, Warner Bros. snapped up movie rights six months before the book

hit the market.

As excitement percolated about ''Heart-Shaped Box,'' so, too, did lingering

questions about its author. Inklings about Hill's family background started

appearing in online message boards in 2005 when his collection of short stories,

''20th Century Ghosts,'' was published in Britain.

Similarities in subject matter and appearance -- Hill has his father's bushy

eyebrows and the dark beard he sported decades ago -- were enough to stir

suspicion among followers of the horror genre.

''It got blogged to death,'' Hill recalled. But only when his identity was

trumpeted in Variety last year did he realize that the secret was gone for good.

''That was really the nail in the coffin,'' he said.

Still, his pen name had a good ride. The editor of ''Heart-Shaped Box'' was

unaware of the King connection and Hill's agent remained in the dark for eight

years before the author spilled the beans two years ago.

Hill's decision to follow his father's career should come as no surprise. His

mother, Tabitha King, has been turning out novels for decades. His younger

brother, Owen King, came out in 2005 with a well-received novella and short

story collection that is more literary than horrific and laced with absurdity.

Like Hill, Owen King wanted to cut his own path and his book did not mention his

parentage. But he decided against a pen name, figuring it would be too much

trouble to try to go by an alias when meeting people or having an agent,

manager, publicist or personal assistant handle details of his professional

life.

The only sibling who has yet to make it into print is Naomi King, oldest of the

three, who has switched careers from restaurateur to Unitarian minister. But

Hill said his sister is working on a nonfiction project: a book-length study of

the sermon as literary text and its place in American culture.

The King children's interest in books and writing took root early on. ''It

sounds very Victorian, but we would sit around and read aloud nightly, in the

living room or on the porch,'' Hill recalled. ''This was something we kept on

doing until I was in high school, at least.''

In an era of celebrity worship, the family has prided itself on being able to

maintain as normal a lifestyle as possible despite Stephen King's fame and

fortune. Hill and his brother attended public high school in Bangor, Maine,

before going on to Vassar College, where they overlapped for one year.

After graduation, Hill and Owen King collaborated on a couple of screenplays.

They sold one, but it has yet to be made into a movie.

The first half of ''Heart-Shaped Box'' is set in New York's Hudson Valley, the

area around Vassar, where Judas Coyne lives with his latest Goth girlfriend, who

30 years his junior, and two devoted German shepherds.

At first, Hill envisioned his tale of a suit with a ghost attached as grist for

a short story. But as he added depth and back story to his characters, it

ballooned into a novel 10 times longer than what he originally planned.

The choice of title was pure serendipity. Hill's initial idea, ''Private

Collection,'' went by the wayside when the 1993 Nirvana song popped up on iTunes

as the author was getting ready to write the episode in which UPS delivers the

haunted suit to Coyne. It was then that Hill decided to package the suit in a

heart-shaped box.

''Coyne is fiction and (Kurt) Cobain was a real guy,'' he said, ''but I felt

that the song fit very well with the book. The song is about a guy who feels

trapped and desperate, and the book is about how someone uses music as a hammer

to beat at the bars of his own cage.''

Hill and his wife, whom he met at Vassar, live in southern New Hampshire with

their three children. He is reluctant to say much about his private life,

recalling how a crazed fan broke into his family's home in Bangor in 1991 and

threatened his mother, a frightening episode that evoked the plot of King's

earlier best seller, ''Misery.''

Stephen King declined a request for comment on his son's novel. ''He's trying to

go along with Joe's wishes and let him do this on his own,'' said his

spokeswoman, Marsha DeFilippo.

But at a recent panel discussion in New York, King told a questioner that he

wouldn't rule out a collaborative book project with his son.

''I guess anything's possible,'' he said. ''I took them on my knee, read them

stories, changed their diapers, and now they're all grown up and they have

become writers, of all things. I am really proud of them. I guess we'll see what

happens down the road.''

Associated Press Writer Colleen Long in New York contributed to this report.

------

On the Net:

http://www.joehillfiction.com

Secret of Horror

Writer's Lineage Broken, NYT, 17.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/AP-Books-Joe-Hill.html

‘Echo Maker’

Wins Book Award for Fiction

November 16, 2006

The New York Times

By JULIE BOSMAN

“The Echo Maker,” an enigmatic novel by

Richard Powers that tells the story of a young man who develops a rare brain

disorder after an automobile accident, won the National Book Award for fiction

last night.

“The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American

Dust Bowl” by Timothy Egan was the surprise winner of the top prize for

nonfiction.

In the book, Mr. Egan, a former New York Times reporter who remains a frequent

contributor to the newspaper, gives an account of the dust storms that descended

on the Great Plains during the Depression.

“Abraham Lincoln said we cannot escape history, but this history of the Dust

Bowl nearly escaped us,” Mr. Egan, a third-generation Westerner, told a crowd of

more than 700 publishers, writers and editors.

As in recent years, the fiction category raised eyebrows in the publishing

industry for its lack of commercially known nominees in a year of big-name

authors.

The awards were presented at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in Manhattan at a

black-tie ceremony, a splashy event drawing many of the most prominent names in

the book publishing industry.

Fran Lebowitz, the writer and humorist, was the evening’s host, appearing in her

trademark tuxedo and white pocket square, and drawing loud cheers when she

paused from poking fun at the show’s organizers to tweak President Bush and his

Iraq policy.

Winners each receive a bronze sculpture and $10,000, although the award’s

greatest benefit is often in increased sales, especially when little-known

authors are suddenly thrust into the spotlight. In addition to Mr. Powers, this

year’s finalists for fiction were Mark Z. Danielewski for “Only Revolutions”

(Pantheon), Ken Kalfus for “A Disorder Peculiar to the Country”

(Ecco/HarperCollins), Dana Spiotta for “Eat the Document” (Scribner/Simon &

Schuster) and Jess Walter for “The Zero” (Judith Regan Books/HarperCollins).

“The Echo Maker” was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Joining Mr. Egan as finalists for nonfiction were Taylor Branch for “At Canaan’s

Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68” (Simon & Schuster); Rajiv

Chandrasekaran for “Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone”

(Alfred A. Knopf); Peter Hessler for “Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China’s

Past and Present” (HarperCollins); and Lawrence Wright for “The Looming Tower:

Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11” (Alfred A. Knopf). Mr. Egan’s publisher was

Houghton Mifflin.

Since 1989, the awards have been presented by the National Book Foundation, but

the prizes were first given in 1950, when Nelson Algren won the fiction award

for “The Man With the Golden Arm” and Ralph L. Rusk won the nonfiction prize for

“The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson.”

In the intervening decades, the roster of winners has included Ralph Ellison for

“Invisible Man” in 1953; Norman Mailer for “The Armies of the Night: History as

a Novel, the Novel as History” in 1969; Saul Bellow for “Mr. Sammler’s Planet”

in 1971; William Styron for “Sophie’s Choice” in 1980; and Philip Roth for

“Sabbath’s Theater” in 1995.

Among last year’s winners were William T. Vollmann, who took the fiction honors

for “Europe Central,” and Joan Didion, who was given the nonfiction prize for

her memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking.”

The winners are decided during a judges’ luncheon on the day of the awards. To

be eligible for this year’s awards, books must have been published between Dec.

1, 2005, and Nov. 30, 2006.

M. T. Anderson received the award for young people’s literature, for “The

Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Volume One: The Pox

Party” (Candlewick Press). The award for poetry went to Nathaniel Mackey for

“Splay Anthem” (New Directions Publishing).

Last night, the foundation also gave two lifetime achievement awards.

Sharing the Literarian Award for outstanding service to the American literary

community yesterday were Robert Silvers and, posthumously, Barbara Epstein,

co-founders and editors of The New York Review of Books. David Remnick, editor

of The New Yorker, presented the award.

Mr. Remnick called The New York Review of Books “never more necessary,” adding

that it is “a guide, an interpreter and a political inspiration in the darkest

of times.”

Adrienne Rich, the author of several nonfiction books and nearly 20 volumes of

poetry, received the foundation’s medal for distinguished contribution to

American letters. In 1974, she won the National Book Award for poetry for

“Diving Into the Wreck.”

In her acceptance speech last night, Ms. Rich rebutted what she called the “free

market critique of poetry,” that the genre is unprofitable, and therefore

useless. But “when poetry lays its hand on our shoulder,” she said, “we can be,

to almost a physical degree, touched and moved.”

‘Echo

Maker’ Wins Book Award for Fiction, NYT, 16.11.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/16/books/16books.html

An instinct for

the future

George Orwell:

The Age's Adversary,

by Patrick Reilly

(Macmillan,

£27.50)

April 10 1986

From The Guardian archive

April 10 1986

The Guardian

1984 unloosed an Orwellian flood of truly Biblical proportions. Here in 1986

the flood starts again. 'The world's evolution,' says the author, 'has placed

him at the heart of our present complexities, and we go to his writing not in

any spirit of aloof research but to find solutions to existing problems.'

This is a wonderful book. Orwell-lovers, Orwell-haters and any benighted

Laodiceans left in the middle should all read it. Socialists should read it,

democratic Socialists; the rest have no right to defile the name.

Who can doubt that 'the collapse of the vision of Socialism' has been 'one of

the great intellectual traumas of the West,' and that therefore the means

whereby Socialism is to be revived both as 'an idea and ideal' is 'for many in

Europe the key question'?

To attempt the task while spurning Orwell is worse than mere arrogance or folly:

it is, almost certainly, an act of cowardice too, the very same charge which

Orwell levelled at so many of his contemporaries.

Patrick Reilly will have none of the nonsense that Orwell himself had deserted

the Socialist cause; he knows his Orwell much too well. True, he could dabble in

patronising references to individual workers or the working class he came to

honour or love. Usually he detected these lapses before anyone else and was

quick to make amends. Usually he paid everyone the compliment of offering the

same kind of personal relations. Only the real underdogs got special treatment.

And sometimes he could see much further, in the interests of his adopted class,

than many of their authentic spokesmen. In the 1930s he realised how insulting

it might be to transfer slum dwellers into working-class ghettos where they

couldn't bring their community ethos. He alone, or almost alone, saw the horror

of tower blocks when they were no more than a malign glint.

Moreover, the lone prophet needed an escape from the wilderness and a pay

packet. He needed them most when all Establishment doors were being slammed in

his face, when he could at first find no publisher for Animal Farm, when no

newspaper for which he wanted to write would publish what he wrote — except

Aneurin Bevan's Tribune. Orwell himself judged Homage to Catalonia his best work

and many will concur. 'The intimacy never fully achieved with the English

working class is miraculously and movingly consummated on the opening page.'

Altogether, what made Orwell such a challenge to all the massed orthodoxies —

what still makes him — was the moulding into one of his art, his character, his

message.

Michael Foot

From The Guardian

archive > April 10 1986 > An instinct for the future >

George Orwell: The Age's

Adversary, by Patrick Reilly (Macmillan, £27.50), G,

Republished 10.4.2007, p.

30,

http://digital.guardian.co.uk/guardian/2007/04/10/pages/ber30.shtml

November 24,

1972

Berger turns tables on Booker

From The Guardian archive

Friday November 24, 1972

Guardian

John Berger last night accepted the Booker

Prize - Britain's biggest annual literary award - and said that he would use the

£5,000 to help the Black Panthers to resist "further exploitation". He said his

object was to turn the prize against its sponsors, Booker McConnell. "Booker

McConnell have had extensive trading interests in the Caribbean for more than

180 years," Mr Berger said.

"The modern poverty of the Caribbean is the

direct result of this and similar exploitation. One of the consequences of this

poverty is that hundreds of thousands of West Indians have been forced to come

to Britain as migrant workers. Thus my book about migrant workers would be

financed directly out of them or their relatives or ancestors."

Mr Berger (who has also won this year's Guardian fiction prize) was speaking at

the Cafe Royal, Regent Street, London, where he accepted the prize from Mr Roy

Jenkins, MP, for his novel "G".

The book was chosen from a list of 50 by Cyril Connolly, Elizabeth Bowen and