|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Books > Readers

17 new books our critics can't

wait to read this summer

NPR May 21,

2025

Illustration: Jackie Lay

17 new books our critics can't

wait to read this summer

NPR

May 21, 2025

6:00 AM ET

https://www.npr.org/2025/05/21/

nx-s1-5356141/best-new-books-summer-reading

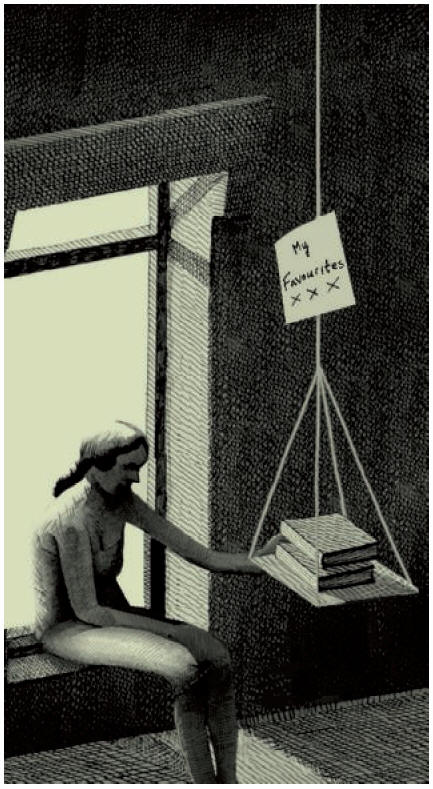

Illustration: Chris Riddell

Neil Gaiman and Chris Riddell

on why we need libraries – an essay in

pictures

Two great champions of reading for pleasure

return to remind us that it really is an

important thing to do

– and that libraries create literate

citizens

G

Thu 6 Sep 2018 16.59 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/sep/06/

neil-gaiman-and-chris-riddell-on-why-we-need-libraries-an-essay-in-pictures

Illustration: Johnny Dombrowski

Can’t Sleep?

Let Stephen King Keep You

Company

NYT

April 19, 2020 5:00 a.m.

ET

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/19/

books/review/stephen-king-if-it-bleeds.html

Illustration: Hanna Barczyk

When Reading Had No End

Books were a refuge in 2020,

although some stories were more

of a consolation than others.

NYT

Dec. 9, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/09/

books/reading-pandemic.html

A young

David Bowie (then Davy Jones) in

1965

fitting in his eight books a day.

Photograph: CA/Redferns

Readers recommend: songs about books

G

Thursday 18 June 2015 20.00 BST

Last modified on Wednesday 15 June 2016 08.11 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2015/jun/18/

readers-recommend-songs-about-books

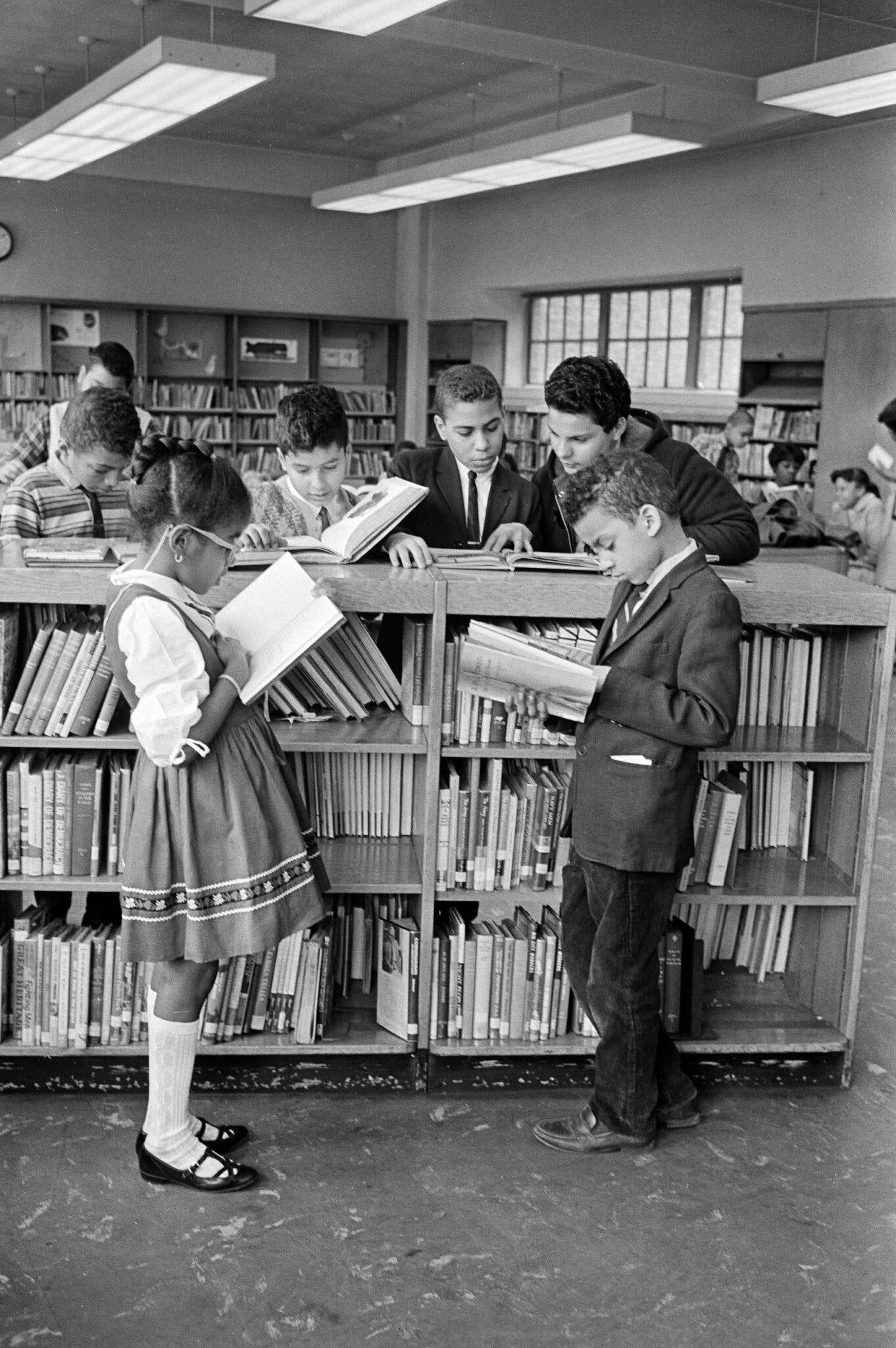

Children reading at the Countee Cullen

Public Library

on 136th Street between Lenox and 7th

Avenues, 1967.

Photograph:

Arthur Brower

The New York Times

Visuals

The Literary Lives of New York City’s Youth

Archival photos of children’s reading rooms

at the New York Public Library over the

years.

NYT

Nov. 10, 2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/10/

books/review/the-literary-lives-of-new-york-citys-youth.html

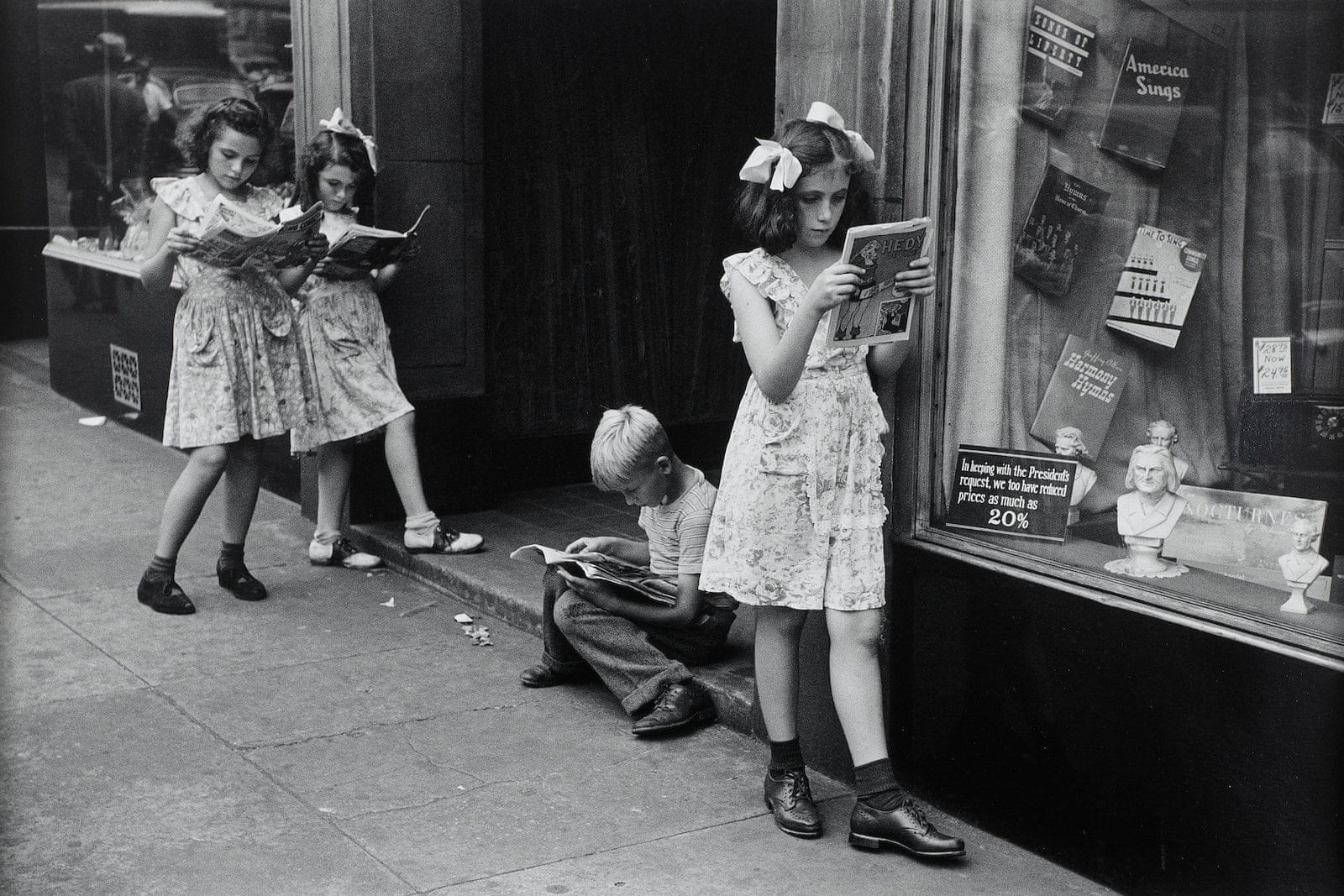

Comic Book Readers, NYC,

1947

In 1940,

Orkin briefly attended Los Angeles City College for

photojournalism

before becoming the first messenger girl at MGM Studios in

1941.

She had hoped to become a cinematographer

but left after discovering that the cinematographers’ union

did not allow female members

American girl behind the camera: the pioneering work of Ruth

Orkin – in pictures

A new auction marks 100 years since the birth of US

photographer Ruth Orkin,

who travelled the world making waves in an industry dominated

by men

G

Tue 12 Jan 2021 07.00 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2021/jan/12/

american-photographer-ruth-orkin-in-pictures

Freshly Squeezed

by Ed Stein

GoComics

June 23, 2013

https://www.gocomics.com/freshlysqueezed/2013/06/23

Readers digest

The Guardian Review

p. 5

30 December 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/dec/30/

bestbooksoftheyear.bestbooks

Readers digest

The Guardian Review

p. 6

30

December 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/dec/30/

bestbooksoftheyear.bestbooks

Izhar Cohen

Guardian Review p. 3

12 March 2005

read UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/sep/06/

neil-gaiman-and-chris-riddell-on-why-we-need-libraries-

an-essay-in-pictures

read

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/26/

books/man-died-book-list-thousands.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/25/

style/fiction-books-men-reading.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/25/

us/reading-literacy-memphis-tennessee.html

https://www.propublica.org/article/

literacy-adult-education-united-states-solutions - December 23, 2022

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/01/

1041859001/reading-aloud-benefits-childrens-literacy

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/30/

991935818/a-joy-of-reading-sparked-

by-a-special-librarian-determined-to-make-a-difference

https://www.npr.org/2019/12/16/

788399531/kids-books-

to-read-again-and-again-and-again-and-again-and-again-and

https://www.npr.org/2019/11/21/

781673493/how-to-read-more-books

https://www.npr.org/2019/03/15/

700345380/building-teens-into-strong-readers-by-letting-them-teach

https://www.npr.org/2019/01/04/

678645947/his-love-for-books-reads-like-poetry

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2018/05/24/

611609366/whats-going-on-in-your-childs-brain-

when-you-read-them-a-story

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2018/03/01/

589912466/dolly-parton-gives-the-gift-of-literacy-a-library-of-100-million-books

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/17/

technology/personaltech/

how-technology-is-and-isnt-changing-our-reading-habits.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/10/19/

498539751/checking-back-in-on-the-barber-who-encourages-kids-to-read

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/10/12/

496553810/choose-a-book-and-read-to-your-barber-hell-take-a-little-money-off-the-top

https://www.npr.org/2016/04/17/

474404440/you-can-go-home-again-the-transformative-joy-of-rereading

https://www.npr.org/blogs/ed/2015/03/17/

387774026/q-a-raising-kids-who-want-to-read

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/13/

opinion/bruni-read-kids-read.html

read aloud

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/01/

1041859001/reading-aloud-benefits-childrens-literacy

the

right to read

USA

https://www.propublica.org/series/

the-right-to-read

https://www.propublica.org/article/

literacy-adult-education-united-states-solutions - December 23, 2022

read

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/06/11/

nx-s1-5002183/fiction-books-summer-2024

literacy

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/25/

us/reading-literacy-memphis-tennessee.html

https://www.propublica.org/article/

literacy-adult-education-united-states-solutions - December 23, 2022

high

school literacy curriculum USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/25/

us/reading-literacy-memphis-tennessee.html

wrestle with complex texts at school

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/25/

us/reading-literacy-memphis-tennessee.html

good read

be a riveting read

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/09/

spy-among-friends-kim-philby-ben-macintyre-review

riveting

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/10/

books/review-in-the-whites-richard-price-tries-on-a-pseudonym-

in-a-world-of-brooding-cops.html

reading

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/oct/06/

the-one-change-that-worked-i-was-lost-in-the-infinite-scroll-

until-a-small-ritual-renewed-my-love-of-reading

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/09/

books/reading-pandemic.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/sep/06/

neil-gaiman-and-chris-riddell-on-why-we-need-libraries-an-essay-

in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/jun/02/

film.schools

reading

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/01/

1041859001/reading-aloud-benefits-childrens-literacy

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/30/

991935818/a-joy-of-reading-sparked-

by-a-special-librarian-determined-to-make-a-difference

http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/07/29/

487934979/cant-buy-me-love-of-reading

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/25/

opinion/the-gift-of-reading.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/

books/review/when-it-comes-to-reading-is-pleasure-suspect.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/

opinion/sunday/how-writing-transforms-us.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/

books/review/the-creator-of-hbos-girls-shares-her-reading-habits.html

reading skills

USA

https://www.npr.org/2019/03/15/

700345380/building-teens-into-strong-readers-by-letting-them-teach

rereading USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/17/

474404440/you-can-go-home-again-the-transformative-joy-of-rereading

reading habits

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/17/

technology/personaltech/how-technology-is-and-isnt-changing-our-reading-habits.html

skim reading

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/aug/25/

skim-reading-new-normal-maryanne-wolf

reader

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/10/

books/review/the-literary-lives-of-new-york-citys-youth.html

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2021/jan/12/

american-photographer-ruth-orkin-

in-pictures - Guardian picture gallery

https://www.npr.org/2019/03/15/

700345380/building-teens-into-strong-readers-by-letting-them-teach

https://www.npr.org/2019/01/04/

678645947/his-love-for-books-reads-like-poetry

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/19/

fashion/a-not-so-young-audience-for-young-adult-books.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/23/

books/review/alice-hoffman-by-the-book.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/aug/05/

will-self-umbrella-booker-interview

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/13/

books/steve-jobs-biography-and-other-hot-titles-bookstore-lures.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/dec/30/

bestbooksoftheyear.bestbooks

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/dec/30/

bestbooksoftheyear.bestbooks1

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/dec/31/

bestbooksoftheyear.bestbooks1

casual reader

avid reader

dyslexic readers

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/childrens-books-site/2015/jan/22/

top-10-books-for-reluctant-and-dyslexic-readers

readership

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/sep/15/

dan-brown-lost-symbol-sales

skim

over N

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Books > Readers, Reading

Page Turner

A Good Mystery: Why We Read

November 25, 2007

The New York Times

By MOTOKO RICH

PERHAPS the most fantastical story of the year was not “Harry Potter and the

Deathly Hallows,” but “The Uncommon Reader,” a novella by Alan Bennett that

imagines the queen of England suddenly becoming a voracious reader late in life.

At a time when books appear to be waging a Sisyphean battle against the forces

of MySpace, YouTube and “American Idol,” the notion that someone could move so

quickly from literary indifference to devouring passion seems, sadly,

far-fetched.

The problem was underscored last week when the National Endowment for the Arts

delivered the sobering news that Americans — particularly teenagers and young

adults — are reading less for fun. At the same time, reading scores among those

who read less are declining, and employers are proclaiming workers deficient in

basic reading comprehension skills.

So that’s the bad news. But is all hope gone, or will people still be drawn to

the literary landscape? And what is it, exactly, that turns someone into a book

lover who keeps coming back for more?

There is no empirical answer. If there were, more books would sell as well as

the “Harry Potter” series or “The Da Vinci Code.” The gestation of a true,

committed reader is in some ways a magical process, shaped in part by external

forces but also by a spark within the imagination. Having parents who read a lot

helps, but is no guarantee. Devoted teachers and librarians can also be

influential. But despite the proliferation of book groups and literary blogs,

reading is ultimately a private act. “Why people read what they read is a great

unknown and personal thing,” said Sara Nelson, editor in chief of the trade

magazine Publishers Weekly.

In some cases, asking someone to explain why they read is to invite an elegant

rationalization. Junot Díaz, the author of “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar

Wao,” vividly recalls stumbling into a mobile library shortly after his family

emigrated from the Dominican Republic to New Jersey when he was 6 years old. He

checked out a Richard Scarry picture book, a collection of 19th-century American

wilderness paintings and a bowdlerized version of Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Sign of

Four.”

So what about those three titles turned him into someone who is crazy for books?

“I could create a narrative explaining the creation myth of my reading frenzy,”

Mr. Díaz said. “But in some ways it’s just provisional. I feel like it’s a

mystery what makes us vulnerable to certain practices and not to others.”

Such caveats aside, there are some clues as to what might transform someone into

an enduring reader.

“The Uncommon Reader” posits the theory that the right book at the right time

can ignite a lifelong habit. (For the fictional queen, it’s Nancy Mitford’s

“Pursuit of Love.”) This is a romantic ideal that persists among many a

bibliophile.

“It can be like a drug in a positive way,” said Daniel Goldin, general manager

of the Harry W. Schwartz Bookshops in Milwaukee. “If you get the book that makes

the person fall in love with reading, they want another one.”

Most often, that experience occurs in childhood. In “The Child That Books

Built,” Francis Spufford, a British journalist and critic, writes of how “the

furze of black marks between ‘The Hobbit’ grew lucid, and released a dragon,”

turning him into “an addict.”

But what makes that one book a trigger for continuous reading? For some, it’s

the discovery that a book’s character is like you, or thinks and feels like you.

In accepting the National Book Award for young people’s literature for “The

Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” earlier this month, Sherman Alexie

thanked Ezra Jack Keats, author of “The Snowy Day,” a classic picture book. “It

was the first time I looked at a book and saw a brown, black, beige character —

a character who resembled me physically and resembled me spiritually, in all his

gorgeous loneliness and splendid isolation,” Mr. Alexie, a Spokane Indian who

grew up on a reservation, told the audience.

In an interview, Mr. Alexie said “The Snowy Day” transformed him from someone

who read regularly into a true bookhound. “I really think it’s the age at which

you find that book that you really identify with that determines the rest of

your reading life,” Mr. Alexie said. “The younger you are when you do that, the

more likely you’re going to be a serious reader. It really is about finding

yourself in a book.”

Of course that doesn’t account for reading for information, enlightenment or

practical advice. And for others, it’s not so much identification as the embrace

of the Other that draws them into reading. “It’s that excitement of trying to

discover that unknown world,” said Azar Nafisi, the author of “Reading Lolita in

Tehran,” the best-selling memoir about a book group she led in Iran.

Sometimes the world of reading is opened up by a book that goes down easy. Mr.

Bennett said he chose “The Pursuit of Love” for his fictional queen because it

happened to be the first adult novel that he read for pleasure. He said that for

him, as with the queen’s character, the book was a stepping off point into more

heavyweight literature. “There are all sorts of entrances that you can get into

reading by reading what might at first seem trash,” Mr. Bennett said.

And certain books that become phenomena — like those in the Harry Potter series

or “The Da Vinci Code” or, to a slightly lesser extent most books recommended

for Oprah Winfrey’s book club — can, in tempting people to read in the first

place, create habitual readers. Perhaps more often, however, those readers just

wait for the next “hot” book.

Indeed, even after Ms. Winfrey recommends a title, sales of other books by the

same author don’t necessarily match those of the book that bears her imprimatur.

“What I find with readers today is they don’t go off on their own to another

book,” said Jonathan Galassi, publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “They wait

for the next recommendation.”

It may also be that for some, reading is a pursuit that, like ballet or

baseball, simply requires practice. “I think for a lot of people, reading is

just something you do,” said Paula Brehm Heeger, president of the Young Adult

Library Services Association. “And you eventually realize that you really like

it.”

Book sales in general are growing only slightly: According to the Book Industry

Study Group, a publishing trade association, the number of books sold last year,

3.1 billion, was up just 0.5 percent from a year earlier.

The question of whether reading, or reading books in particular, is essential is

complicated by the fact that part of what draws people to books can now be found

elsewhere — and there is only so much time to consume it all.

Readers who want to know they are not alone are finding reflections of

themselves in the confessional blogs sprouting across the Internet. And

television shows like “The Sopranos” or “Lost” can satisfy the hunger for

narrative and richly textured characters in a way that only books could in a

previous age.

But books have outlived many death knells, and are likely to keep doing so. “I’m

much more optimistic than I think most people are,” Mr. Díaz said. Reading

suffers, he said, because it has to compete unfairly with movies, television

shows and electronic gadgets whose marketing budgets far outstrip those of

publishers. “Books don’t have billion-dollar publicity behind them,” Mr. Díaz

said. “Given the fact that books don’t have that, they’re not doing a bad job.”

A Good Mystery: Why We

Read,

NYT,

25.11.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/25/

weekinreview/25rich.html

Potter Has Limited Effect

on Reading Habits

July 11, 2007

The New York Times

By MOTOKO RICH

Of all the magical powers wielded by Harry Potter, perhaps none has cast a

stronger spell than his supposed ability to transform the reading habits of

young people. In what has become near mythology about the wildly popular series

by J. K. Rowling, many parents, teachers, librarians and booksellers have

credited it with inspiring a generation of kids to read for pleasure in a world

dominated by instant messaging and music downloads.

And so it has, for many children. But in keeping with the intricately plotted

novels themselves, the truth about Harry Potter and reading is not quite so

straightforward a success story. Indeed, as the series draws to a much-lamented

close, federal statistics show that the percentage of youngsters who read for

fun continues to drop significantly as children get older, at almost exactly the

same rate as before Harry Potter came along.

There is no doubt that the books have been a publishing sensation. In the 10

years since the first one, “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” was

published, the series has sold 325 million copies worldwide, with 121.5 million

in print in the United States alone. Before Harry Potter, it was virtually

unheard of for kids to queue up for a mere book. Children who had previously

read short chapter books were suddenly plowing through more than 700 pages in a

matter of days. Scholastic, the series’s United States publisher, plans a

record-setting print run of 12 million copies for “Harry Potter and the Deathly

Hallows,” the eagerly awaited seventh and final installment due out at 12:01

a.m. on July 21.

But some researchers and educators say that the series, in the end, has not

permanently tempted children to put down their Game Boys and curl up with a book

instead. Some kids have found themselves daunted by the growing size of the

books (“Sorcerer’s Stone” was 309 pages; “Deathly Hallows,” will be 784). Others

say that Harry Potter does not have as much resonance as titles that more

realistically reflect their daily lives. “The Harry Potter craze was a very

positive thing for kids,” said Dana Gioia, chairman of the National Endowment

for the Arts, who has reviewed statistics from federal and private sources that

consistently show that children read less as they age. “It got millions of kids

to read a long and reasonably complex series of books. The trouble is that one

Harry Potter novel every few years is not enough to reverse the decline in

reading.”

Educators agree that the series can’t get the job done alone.

“Unless there are scaffolds in place for kids — an enthusiastic adult saying,

‘Here’s the next one’ — it’s not going to happen,” said Nancie Atwell, the

author of “The Reading Zone: How to Help Kids Become Skilled, Passionate,

Habitual, Critical Readers” and a teacher in Edgecomb, Me. “And in way too many

American classrooms it’s not happening.”

Young people are less inclined to read for pleasure as they move into their

teenage years for a variety of reasons, educators say. Some of these are trends

of long standing (older children inevitably become more socially active, spend

more time on reading-for-school or simply find other sources of entertainment

other than books), and some are of more recent vintage (the multiplying

menagerie of high-tech gizmos that compete for their attention, from iPods to

Wii consoles). What parents and others hoped was that the phenomenal success of

the Potter books would blunt these trends, perhaps even creating a generation of

lifelong readers in their wake.

“Anyone who has children or grandchildren sees the competition for children’s

time increasing as they enter adolescence, and the difficulty that reading seems

to have to compete effectively,” Mr. Gioia said.

Many thousands of children have, indeed, gone from the Potter books to other

pleasure reading. But others have dropped away.

Starting when Avram Leierwood was 7, he would read the books aloud with his

mother, Mina. “We’d sit in the treehouse in our backyard and take turns,”

recalled Ms. Leierwood, of South Minneapolis.

But while Ms. Leierwood has remained an avid fan, Avram, now 15, is indifferent.

When “Deathly Hallows” comes out, he will be on a canoe trip. As for reading, he

said: “I don’t really have much time anymore. I like to hang out with my

friends, talk, go watch movies and stuff, go to the park and play ultimate

Frisbee.”

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a series of

federal tests administered every few years to a sample of students in grades 4,

8 and 12, the percentage of kids who said they read for fun almost every day

dropped from 43 percent in fourth grade to 19 percent in eighth grade in 1998,

the year “Sorcerer’s Stone” was published in the United States. In 2005, when

“Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince,” the sixth book, was published, the

results were identical.

Many parents, educators and librarians say that despite such statistics, they

have seen enough evidence to convince them that Harry Potter is a bona fide

hero.

“Parents will say, ‘You know, my son never spent time reading, and now my son is

staying up late reading, keeping the light on because he can’t put that book

down,’ ” said Linda B. Gambrell, president of the International Reading

Association, a professional organization for teachers.

In a study commissioned last year by Scholastic, Yankelovich, a market research

firm, reported that 51 percent of the 500 kids aged 5 to 17 polled said they did

not read books for fun before they started reading the series. A little over

three-quarters of them said Harry Potter had made them interested in reading

other books.

Before she discovered Harry Potter, Kara Havranek, 13, spent most of her time

romping outside in Parma, a suburb of Cleveland, or playing video games like

Crash Bandicoot.

But four years after struggling through “Sorcerer’s Stone,” Kara has read and

reread all six books, decorated her bedroom with Potter memorabilia and said she

could hardly wait for “Deathly Hallows.”

But although Kara said she has enjoyed other books, she was not sure what

lasting influence the series would have. “I probably won’t read as much when

Harry Potter is over,” she said.

In a way that was previously rare for books, Harry Potter entered the

pop-culture consciousness. The movies (the film version of “Harry Potter and the

Order of the Phoenix,” the fifth in the series, just opened) heightened the

fervor, spawning video games and collectible figurines. That made it easier for

kids who thought reading was for geeks to pick up a book.

Until Harry Potter, “I don’t think kids were reading proudly,” said Connie

Williams, the school librarian at Kenilworth Junior High School in Petaluma,

Calif. “Now it’s more normalized. It’s like, ‘Gosh we can read now, it’s O.K.’ ”

But creating a habit of reading is a continuous battle with kids who are

saturated with other options. During a recent sixth-grade English class at the

John W. McCormack Middle School in the Dorchester section of Boston, Aaron

Forde, a cherubic 12-year-old, said he loved playing soccer, basketball and

football. On top of that, he spends four hours a day chatting with friends on

MySpace.com, the social networking site.

He had read the first three Harry Potter books, but said he had no particular

interest in reading more. “I don’t like to read that much,” he said. “I think

there are better things to do.”

Neema Avashia, Aaron’s English teacher, said it was rare for the Harry Potter

series to draw reluctant readers to books. “I try to have a lot of books in my

library that reflect where kids are coming from,” Ms. Avashia said. “And Harry

Potter isn’t really where my kids are coming from.” She noted that her class is

85 percent nonwhite, and Harry Potter has few characters that belong to a racial

minority group.

Some reading experts say that urging kids to read fiction in general might be a

misplaced goal. “If you look at what most people need to read for their

occupation, it’s zero narrative,” said Michael L. Kamil, a professor of

education at Stanford University. “I don’t want to deny that you should be

reading stories and literature. But we’ve overemphasized it,” he said. Instead,

children need to learn to read for information, Mr. Kamil said, something they

can practice while reading on the Internet, for example.

Still, there is something about seeing the passion that a novel can inspire that

excites those who want to perpetuate a culture of reading. Even as the Harry

Potter series draws to a close, there are signs that other books are coming up

to take its place.

On a recent afternoon at at Public School 54 on Staten Island, a group of fifth

grade boys shouted with enthusiasm for the “Cirque du Freak” series by Darren

Shan, about a boy who becomes entangled with a vampire.

“I like the books so much that even when the teacher is teaching a lesson, I

still want to read the books,” said Vincent Eng, a wiry 11-year-old. His

classmate Thejas Alex said he had stopped reading a Harry Potter book to jump

into “Cirque du Freak.”

“While I was reading them,” Thejas said, referring to the “Cirque” books, “I was

like, addicted.”

Potter Has Limited

Effect on Reading Habits,

NYT,

11.7.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/11/

books/11potter.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

books

arts

education, learning,

school, universities / colleges > UK

education,

learning,

school, universities / colleges > USA

learning disability > dyslexia

Related > Anglonautes >

Arts

books

|