|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Toys and games

Outdoor activities, Board games

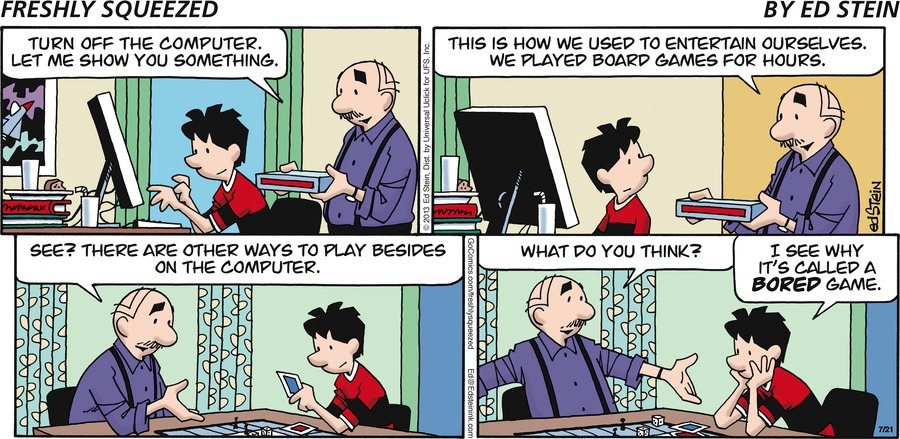

Freshly Squeezed

by Ed Stein

GoComics

July 21, 2013

https://www.gocomics.com/freshlysqueezed/2013/07/21

#.Uray8vTuKAk

Dungeons & Dragons Online: Stormreach

Game Spy PC

http://uk.media.pc.gamespy.com/media/619/619908/img_5195285.html

http://uk.media.pc.gamespy.com/media/619/619908/imgs_1.html

added 9.3.2008

slightly right cropped by Anglonautes

tabletop role-playing game > Dungeons & Dragons

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/09/20/

g-s1-23824/as-dungeons-dragons-turns-50-this-year-

we-asked-listeners-for-their-stories-about-the-game-here-are-5

http://www.npr.org/2015/10/27/

450881148/after-40-years-dungeons-dragons-still-brings-players-to-the-table

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/27/us/

27dungeons.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/05/

arts/05gygax.html

checkers USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/30/

us/30fortman.html

board games UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/dec/17/

board-games-christmas

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/gallery/2009/nov/27/

10-best-board-games

board games USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2018/01/09/

575952575/fighting-bias-with-board-games

https://www.npr.org/2016/07/24/

484356521/amid-board-game-boom-

designers-roll-the-dice-on-odd-ideas-even-exploding-cows

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/06/

technology/high-tech-push-has-board-games-rolling-again.html

The Settlers of Catan

Klaus Teuber (...)

created one of the best-selling board games of all time.

The Settlers of Catan

was first released in 1995,

and now the game known as Catan

has sold more than 40 million units

in nearly 50 languages all over the world,

as well as in video game versions.

https://www.npr.org/2023/04/05/

1168256131/catan-board-game-klaus-teuber-dies

tabletop games

USA

https://www.npr.org/2015/10/27/

450881148/after-40-years-dungeons-dragons-still-brings-players-to-the-table

dice USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/16/

business/16monopoly.html

cribbage UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2023/jun/09/

belfast-karakoram-mountains-photography-alain-le-garsmeur

Buffalo USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2018/01/09/

575952575/fighting-bias-with-board-games

Monopoly

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Monopoly_(game)

Monopoly mobile banking app

USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/03/15/

nx-s1-5325943/opinion-monopoly-money-is-going-digital

Monopoly > token UK

https://www.guardian.co.uk/news/blog/poll/2013/jan/09/

monopoly-hasbro-new-token-vote

The Landlord's Game > Monopoly

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/12/

obituaries/lizzie-magie-overlooked.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/

business/behind-monopoly-an-inventor-who-didnt-pass-go.html

new version of Monopoly

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/16/

business/16monopoly.html

The Wire Monopoly UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/mediamonkeyblog/2010/oct/07/

the-wire-monopoly

Hasbro's new edition of Monopoly,

complete with batteries and inflated house prices

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/oct/27/

monopoly-christmas-toy-bestseller

jigsaw puzzles

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/11/09/

932652740/puzzle-business-goes-bonkers-

as-people-seek-pandemic-pastimes-at-home

Scrabble USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/07/08/

889246690/scrabble-association-bans-racial-ethnic-slurs-

from-its-official-word-list

Scrabble UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/aug/13/

scrabble-champion-crowned-buffalo

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/

the-sublime-joy-of-scrabble-1067061.html

Trivial Pursuit USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/03/

business/03haney.html

crossword USA

https://www.nytimes.com/crosswords

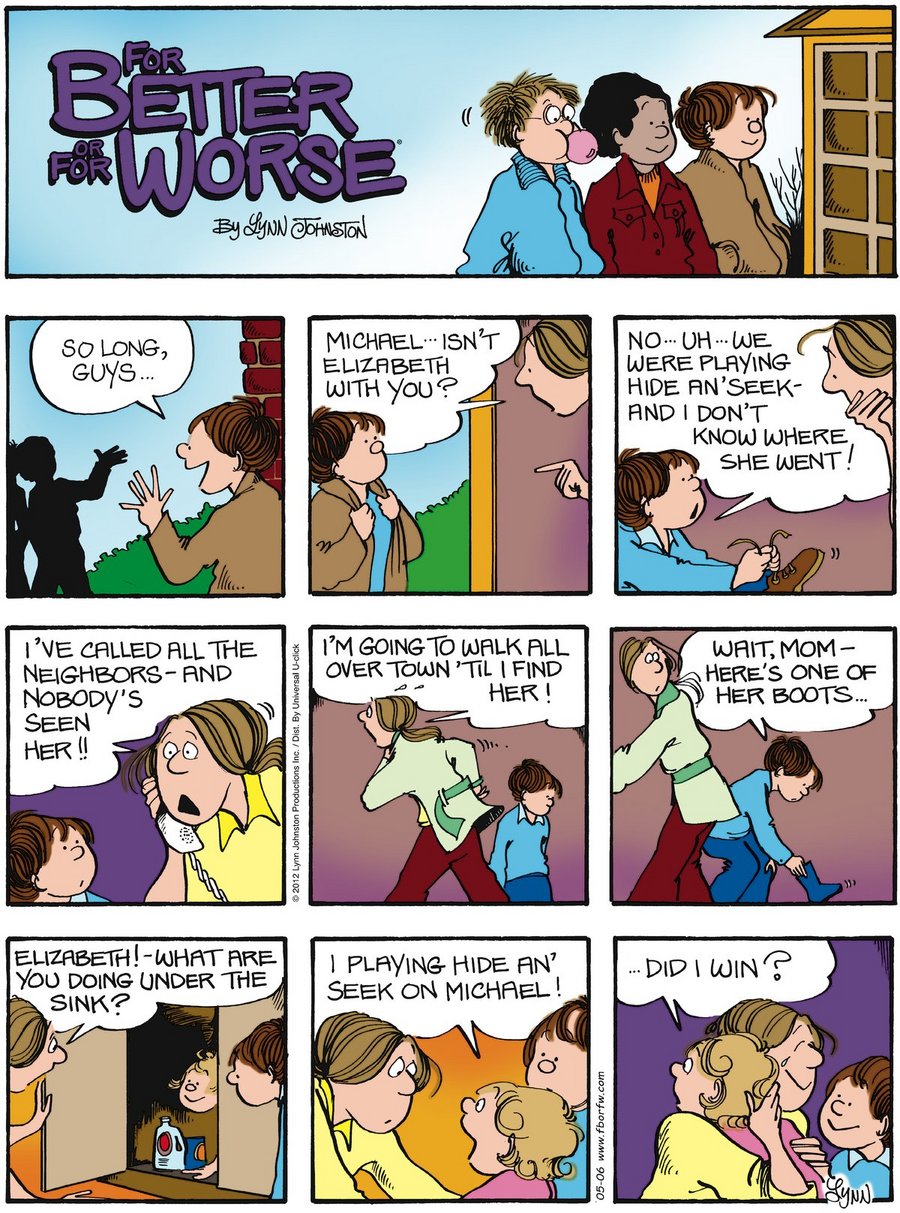

For Better and For Worse

by Lynn Johnston

GoComics

May 6, 2012

outdoor activity UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/may/21/

children-weaker-computers-replace-activity

hopscotch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Hopscotch

snakes and ladders

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Snakes_and_ladders

merry-go-round

hide and seek

sliding

swinging

climbing

Corpus of news articles

Games

> Outdoor activities, Board games

No Dice, No Money, No Cheating.

Are You Sure This Is Monopoly?

February 15, 2011

The New York Times

By STEPHANIE CLIFFORD

You can still collect $200 when you pass “Go,” but not in piles of play

money.

In the new version of Monopoly, the game’s classic pastel-colored bills and the

designated Banker have been banished, along with other old-fashioned elements,

in favor of a computer that runs the game.

Hasbro showed a preview of the new version, called Monopoly Live, at this week’s

Toy Fair in New York. It is the classic Monopoly board on the outside, with the

familiar railroads like the B.& O. and the development of property. But in the

center, instead of dice and Chance and Community Chest cards, an infrared tower

with a speaker issues instructions, keeps track of money and makes sure players

adhere to the rules. The all-knowing tower even watches over advancing the

proper number of spaces.

Hasbro hopes the computerized Monopoly will appeal to a generation raised on

video games amid a tough market for traditional board games, a category where

sales declined 9 percent in 2010, according to the market-research firm NPD

Group. “How do we give them the video game and the board game with the social

experience? That’s where Monopoly Live came in,” said Jane Ritson-Parsons,

global brand leader for Monopoly.

With free digital games everywhere, Hasbro is hoping to revive interest among

young children and preteenagers in several of its games that cost money. (The

new Monopoly, available in the fall, will be about $50). Battleship will undergo

a similar digital upgrade this year, and other Hasbro games will be redesigned

for 2012 and 2013, Ms. Ritson-Parsons said.

But for families used to arguing over Monopoly’s rules, players who slip a $100

bill under the board for later use and friends who gleefully demand rent from

one another, it may not be so easy to adapt to a computer’s presence on the

board.

“It seems that there’s a computer that makes most of the decisions for you — it

changes a lot of the rules, it removes a lot of the skill,” said Ken Koury, a

competitive Monopoly player and coach who informally settles rule disputes for

others. “With this computer, I’m wondering what’s left for the player to decide

— is it they just keep pushing buttons and wait for someone to win?”

Hasbro is aiming at luring 8- to 12-year-olds back to these board games. Its

executives say this age group, accustomed to video games, wants a fast-paced

game that requires using their hands. To move forward on the new Monopoly board,

players cover their game piece with their hands, and the tower announces how

many spaces the player can move. Players also hold their hands over decals to

buy or sell properties, insert “bank cards” into slots to check their accounts,

and send a plastic car moving around a track to win money or other advantages

(only when the tower instructs them to, of course).

Hasbro executives also say that young players do not want to bother with reading

instructions and toss rules aside.

“For games, but really for anything you buy today, you need to be able to take

it out of the box and play it,” said John Frascotti, Hasbro’s chief marketing

officer. “You’re not ensconced in the rulebook.”

To that end, Hasbro is shortening and simplifying many of its popular games,

changing the formats of Scrabble and Cranium so they can be played in

five-minute spurts. Rivals like Mattel are doing the same with games like Apples

to Apples. Even video games often come in bite-size pieces, like the popular

Angry Birds.

"There is a recognition that people’s attention spans maybe aren’t as big as

they used to be, or they don’t have the time to dedicate to this activity," said

Sean McGowan, a toy analyst with Needham & Company.

Ms. Ritson-Parsons said that while some aspects of the game had changed,

Monopoly Live still emphasized social interaction.

“Getting rid of the instruction book encourages a lot more face-to-face

interaction,” she said. “If you’re not having to read as much, you are all

chatting more.”

Hasbro has kept key social elements, like allowing negotiation for property.

The adherence to rules also speeds up the game and makes it more interesting,

she said. For example, if a player lands on Marvin Gardens but decides not to

buy it, the rules mandate that it be auctioned off right away — but a lot of

players do not know or do not follow that rule.

“People were saying, ‘It takes me a while to get to own properties,’ ” Ms.

Ritson-Parsons said. “Well, it’s going to if you don’t auction it.”

The new version tries to combat board boredom in other ways. It sprinkles in

random events, like a horse race where players must bet on winners.

The computer also tracks how fast or slow play is going, and may intervene to

make it lively. If, say, very little property is getting bought, it will

announce an auction in the middle of turns.

Hasbro executives said that the company would continue to sell classic Monopoly

once the new edition came out.

“It’s really just an extension of the brand, not a destruction of what was,” Mr.

Frascotti said.

Mary Flanagan, a game designer and distinguished professor of digital humanities

at Dartmouth, said that games tended to reflect the societies that they were

played in. For instance, the original Monopoly, issued in 1935 by Parker

Brothers, now a subsidiary of Hasbro, reflected “American ingenuity, the sense

of needing to have hope, and reinforcing capitalism in the face of real economic

despair,” she said.

This version, she said, seemed to be “less and less about financial awareness” —

children do not need math skills in it— and more about social interaction.

Yet “when you say you can’t cheat, it means that there’s no sense of being able

to socially negotiate the rules,” she said.

Joey Lee, who studies games as an assistant professor of technology and

education at Teachers College at Columbia University, said cheating could

actually be instructional.

“I wouldn’t necessarily even call it cheating,” he said. “In many cases a

gamer’s mind-set is coming up with new and novel approaches to winning, and to a

certain problem at hand. That’s exactly the kind of mind-set we need as far as

21st-century skills.”

“Being able to negotiate with others, make up your own rules, argue with other

players, that, to me, is part of what makes it a successful social game,” he

said. The tower is “more of that blind adherence to following orders, versus

being able to figure out and learn the game for yourself.”

Though Hasbro is emphasizing social interaction with the game, some Monopoly

players and academics said the new version sounded much less social — no arguing

over whether a player could buy his neighbor’s “Get Out of Jail Free” card?

“It takes away from the aspect of interpersonal negotiations if you have an

electronic voice in the middle of the board telling you everything to do,” said

Dale Crabtree, a finalist in the national Monopoly championships in 2009. “The

first thing I said was, ‘The next thing they’ll do away with is the players.’ ”

No Dice, No Money, No

Cheating. Are You Sure This Is Monopoly?,

NYT,

15.2.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/16/

business/16monopoly.html

Richard L. Fortman,

a Champion at Checkers,

Dies at 93

November 30, 2008

The New York Times

By MARGALIT FOX

Richard L. Fortman, an internationally known authority on checkers, the sport

of men and kings, died on Nov. 8 in Springfield, Ill. He was 93 and a lifelong

resident of Springfield.

His daughter, Cindy Ponder, confirmed the death.

For seven decades Mr. Fortman was considered one of the game’s foremost players,

analysts and authors. He was almost certainly the last living link to the heyday

of checkers in the era before television, when men passed the time playing in

barbershops and firehouses and city parks, and when high-pressure tournaments

took place in smoke-filled rooms where the prevailing hush was broken only by a

rhythmic click-click-clicking.

A specialist in the slow, ruminative art of checkers by mail, Mr. Fortman was a

former world postal checkers champion. His series of handbooks, “Basic

Checkers,” published privately in seven volumes in the 1970s and ’80’s, is

widely considered the Hoyle of checkers, required reading for students of the

game.

In the hands of a master checkers is no child’s play, and Mr. Fortman was quite

literally a master. (Like chess players, checkers players are ranked

internationally, the most extraordinary becoming masters and grandmasters.) In

his prime Mr. Fortman was one of the top players in the world. He could play

blindfolded. He could play 100 games at once. He won most of them.

Like chess, checkers is played on a board of 64 squares. Unlike chess, it is

played only on the black, the F sharp major of the gaming world. Pieces, or

“men,” as they are known, move on the diagonal. It is a game of relentless,

incremental forward motion: only when a piece reaches the farthest row and

becomes a king may it move in reverse. These tight restrictions on allowable

moves, players say, make checkers in many respects more difficult than chess.

There are about 500 billion billion possible positions on a checkerboard —

visualize a 5 with 20 zeros after it — and players study historical openings and

endgames with the fervor of initiates to priestly ritual. The hold checkers

exerts on the faithful can border on obsession; at its most tenacious, adherents

say, it has been the ruin of more than one man. Happily, Mr. Fortman, by all

accounts a solid citizen who earned his living as a warehouseman, was not among

them.

Richard Lee Fortman was born in Springfield on Feb. 8, 1915. His father, Richard

Clarence, was a railroad telegrapher, and late at night, when few trains came,

he and his co-workers along the line played checkers by telegraph. They could

not betray themselves by keeping checkerboards in the stations, so the games

played out entirely in their heads.

At home, father and son passed long winter evenings at the board. With years of

telegraphy under his belt, the father routinely trounced the son. When the son

was about 15, his father, an intuitive player, suggested he consult books on

checkers in the local library. Young Mr. Fortman did so, and after about a year

began thrashing his father. The father revised his position on checkers books.

In 1933, at 18, Mr. Fortman entered his first state tournament and placed third.

(Between 1950 and 1978, he was Illinois state champion six times.) After Army

service in Italy and North Africa in World War II, he joined the Panhandle

Eastern Pipe Line Company, becoming a warehouse foreman there.

Mr. Fortman married Faye Nichols in 1950. Their home was awash in checkers, with

games in various states of play scattered throughout the house. When his

children were young and dangerous, Mr. Fortman set up his boards in the basement

of his parents’ home, located conveniently next door.

In correspondence checkers, Mr. Fortman’s particular passion, a player has

perhaps 72 hours to plot and ponder before writing his next move on a postcard

and sending it to his opponent. A game unfolds over many months, sometimes

almost a year. Mr. Fortman won the world postal championship in 1986 and again

in 1990.

Besides his wife and daughter, both of Springfield, Mr. Fortman is survived by a

son, Mark, of Westmont, Ill.; a sister, June Russell of Springfield; and four

grandchildren.

In recent years the computer has made checkers by mail a bygone art. Mr. Fortman

adapted, and to the end of his life, his daughter said, he spent hours each day

playing, and winning, games online. Last month members of the checkers world

suspected that Mr. Fortman’s health was declining after he failed, highly

uncharacteristically, to submit his return moves in time.

Richard L. Fortman, a

Champion at Checkers, Dies at 93, NYT, 30.11.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/30/

us/30fortman.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Geek Love

March 9, 2008

The New York Times

By ADAM ROGERS

San Francisco

GARY GYGAX died last week and the universe did not collapse. This surprises me a

little bit, because he built it.

I’m not talking about the cosmological, Big Bang part. Everyone who reads blogs

knows that a flying spaghetti monster made all that. But Mr. Gygax co-created

the game Dungeons & Dragons, and on that foundation of role-playing and

polyhedral dice he constructed the social and intellectual structure of our

world.

Dungeons & Dragons was a brilliant pastiche, mashing together tabletop war

games, the Conan-the-Barbarian tales of Robert E. Howard and a magic trick from

the fantasy writer Jack Vance with a dash of Bulfinch’s mythology, a bit of the

Bible and a heaping helping of J. R. R. Tolkien.

Mr. Gygax’s genius was to give players a way to inhabit the characters inside

their games, rather than to merely command faceless hordes, as you did in, say,

the board game Risk. Roll the dice and you generated a character who was

quantified by personal attributes like strength or intelligence.

You also got to pick your moral alignment, like whether you were “lawful good”

or “chaotic evil.” And you could buy swords and fight dragons. It was cool.

Yes, I played a little. In junior high and even later. Lawful good paladin. Had

a flaming sword. It did not make me popular with the ladies, or indeed with

anyone. Neither did my affinity for geometry, nor my ability to recite all of

“Star Wars” from memory.

Yet on the strength of those skills and others like them, I now find myself on

top of the world. Not wealthy or in charge or even particularly popular, but in

instead of out. The stuff I know, the geeky stuff, is the stuff you and everyone

else has to know now, too.

We live in Gary Gygax’s world. The most popular books on earth are fantasy

novels about wizards and magic swords. The most popular movies are about

characters from superhero comic books. The most popular TV shows look like

elaborate role-playing games: intricate, hidden-clue-laden science fiction

stories connected to impossibly mathematical games that live both online and in

the real world. And you, the viewer, can play only if you’ve sufficiently

mastered your home-entertainment command center so that it can download a

snippet of audio to your iPhone, process it backward with beluga whale harmonic

sequences and then podcast the results to the members of your Yahoo group.

Even in the heyday of Dungeons & Dragons, when his company was selling millions

of copies and parents feared that the game was somehow related to Satan worship,

Mr. Gygax’s creation seemed like a niche product. Kids played it in basements

instead of socializing. (To be fair, you needed at least three people to play —

two adventurers and one Dungeon Master to guide the game — so Dungeons & Dragons

was social. Demented and sad, but social.) Nevertheless, the game taught the

right lessons to the right people.

Geeks like algorithms. We like sets of rules that guide future behavior. But

people, normal people, consistently act outside rule sets. People are messy and

unpredictable, until you have something like the Dungeons & Dragons character

sheet. Once you’ve broken down the elements of an invented personality into

numbers generated from dice, paper and pencil, you can do the same for your real

self.

For us, the character sheet and the rules for adventuring in an imaginary world

became a manual for how people are put together. Life could be lived as a kind

of vast, always-on role-playing campaign.

Don’t give me that look. I know I’m not a paladin, and I know I don’t live in

the Matrix. But the realization that everyone else was engaged in role-playing

all the time gave my universe rules and order.

We geeks might not be able to intuit the subtext of a facial expression or a

casual phrase, but give us a behavioral algorithm and human interactions become

a data stream. We can process what’s going on in the heads of the people around

us. Through careful observation of body language and awkward silences, we can

even learn to detect when we are bringing the party down with our analysis of

how loop quantum gravity helps explain the time travel in that new “Terminator”

TV show. I mean, so I hear.

Mr. Gygax’s game allowed geeks to venture out of our dungeons, blinking against

the light, just in time to create the present age of electronic miracles.

Dungeons & Dragons begat one of the first computer games, a swords-and-sorcery

dungeon crawl called Adventure. In the late 1970s, the two games provided the

narrative framework for the first fantasy-based computer worlds played by

multiple, remotely connected users. They were called multi-user dungeons back

then, and they were mostly the province of students at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology. But they required the same careful construction of

virtual identities that Mr. Gygax had introduced to gaming.

Today millions of people are slaves to Gary Gygax. They play EverQuest and World

of Warcraft, and someone must still be hanging out in Second Life. (That

“massively multiplayer” computer traffic, by the way, also helped drive the

development of the sort of huge server clouds that power Google.)

But that’s just gaming culture, more pervasive than it was in 1974 when Dungeons

& Dragons was created and certainly more profitable — today it’s estimated to be

a $40 billion-a-year business — but still a little bit nerdy. Delete the

dragon-slaying, though, and you’re left with something much more mainstream:

Facebook, a vast, interconnected universe populated by avatars.

Facebook and other social networks ask people to create a character — one based

on the user, sure, but still a distinct entity. Your character then builds

relationships by connecting to other characters. Like Dungeons & Dragons, this

is not a competitive game. There’s no way to win. You just play.

This diverse evolution from Mr. Gygax’s 1970s dungeon goes much further. Every

Gmail login, every instant-messaging screen name, every public photo collection

on Flickr, every blog-commenting alias is a newly manifested identity, a

character playing the real world.

We don’t have to say goodbye to Gary Gygax, the architect of the now. Every time

I make a tactical move (like when I suggest to my wife this summer that we

should see “Iron Man” instead of “The Dark Knight”), I’m counting my experience

points, hoping I have enough dexterity and rolling the dice. And every time, Mr.

Gygax is there — quasi-mystical, glowing in blue and bearing a simple game that

was an elegant weapon from a more civilized age.

That was a reference to “Star Wars.” Cool, right?

Adam Rogers is a senior editor at Wired.

Geek Love, NYT,

9.3.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/09/

opinion/09rogers.html

Gary Gygax,

Game Pioneer,

Dies at 69

March 5,

2008

The New York Times

By SETH SCHIESEL

Gary Gygax,

a pioneer of the imagination who transported a fantasy realm of wizards, goblins

and elves onto millions of kitchen tables around the world through the game he

helped create, Dungeons & Dragons, died Tuesday at his home in Lake Geneva, Wis.

He was 69.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Gail Gygax, who said he had been ailing and

had recently suffered an abdominal aneurysm, The Associated Press reported.

As co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, the seminal role-playing game introduced in

1974, Mr. Gygax wielded a cultural influence far broader than his relatively

narrow fame among hard-core game enthusiasts.

Before Dungeons & Dragons, a fantasy world was something to be merely read about

in the works of authors like J. R. R. Tolkien and Robert Howard. But with

Dungeons & Dragons, Mr. Gygax and his collaborator, Dave Arneson, created the

first fantasy universe that could actually be inhabited. In that sense, Dungeons

& Dragons formed a bridge between the noninteractive world of books and films

and the exploding interactive video game industry. It also became a commercial

phenomenon, selling an estimated $1 billion in books and equipment. More than 20

million people are estimated to have played the game.

While Dungeons & Dragons became famous for its voluminous rules, Mr. Gygax was

always adamant that the game’s most important rule was to have fun and to enjoy

the social experience of creating collaborative entertainment. In Dungeons &

Dragons, players create an alternate persona, like a dwarven thief or a noble

paladin, and go off on imagined adventures under the adjudication of another

player called the Dungeon Master.

“The essence of a role-playing game is that it is a group, cooperative

experience,” Mr. Gygax said in a telephone interview in 2006. “There is no

winning or losing, but rather the value is in the experience of imagining

yourself as a character in whatever genre you’re involved in, whether it’s a

fantasy game, the Wild West, secret agents or whatever else. You get to sort of

vicariously experience those things.”

When Mr. Gygax (pronounced GUY-gax) first published Dungeons & Dragons under the

banner of his company, Tactical Studies Rules, the game appealed mostly to

college-age players. But many of those early adopters continued to play into

middle age, even as the game also trickled down to a younger audience.

“It initially went to the college-age group, and then it worked its way backward

into the high schools and junior high schools as the college-age siblings

brought the game home and the younger ones picked it up,” Mr. Gygax said.

Mr. Gygax’s company, renamed TSR, was acquired in 1997 by Wizards of the Coast,

which was later acquired by Hasbro, which now publishes the game.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Gygax is survived by six children: three sons,

Ernest G. Jr., Lucion Paul and Alexander; and three daughters, Mary Elise, Heidi

Jo and Cindy Lee.

These days, pen-and-paper role-playing games have largely been supplanted by

online computer games. Dungeons & Dragons itself has been translated into

electronic games, including Dungeons & Dragons Online. Mr. Gygax recognized the

shift, but he never fully approved. To him, all of the graphics of a computer

dulled what he considered one of the major human faculties: the imagination.

“There is no intimacy; it’s not live,” he said of online games. “It’s being

translated through a computer, and your imagination is not there the same way it

is when you’re actually together with a group of people. It reminds me of one

time where I saw some children talking about whether they liked radio or

television, and I asked one little boy why he preferred radio, and he said,

‘Because the pictures are so much better.’ ”

Gary Gygax, Game Pioneer, Dies at 69,

NYT,

March 5, 2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/05/

arts/05gygax.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

arts > toys, games

arts

|