|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Toys and games >

Board games >

Chess

Chess Champion Bobby Fischer

Date taken: 1962

Photograph:

Carl Mydans

Life Images

Anglonautes: Wrong Life caption ? - the man in the

picture

may

not be Chess Champion Bobby Fischer (1943-2008).

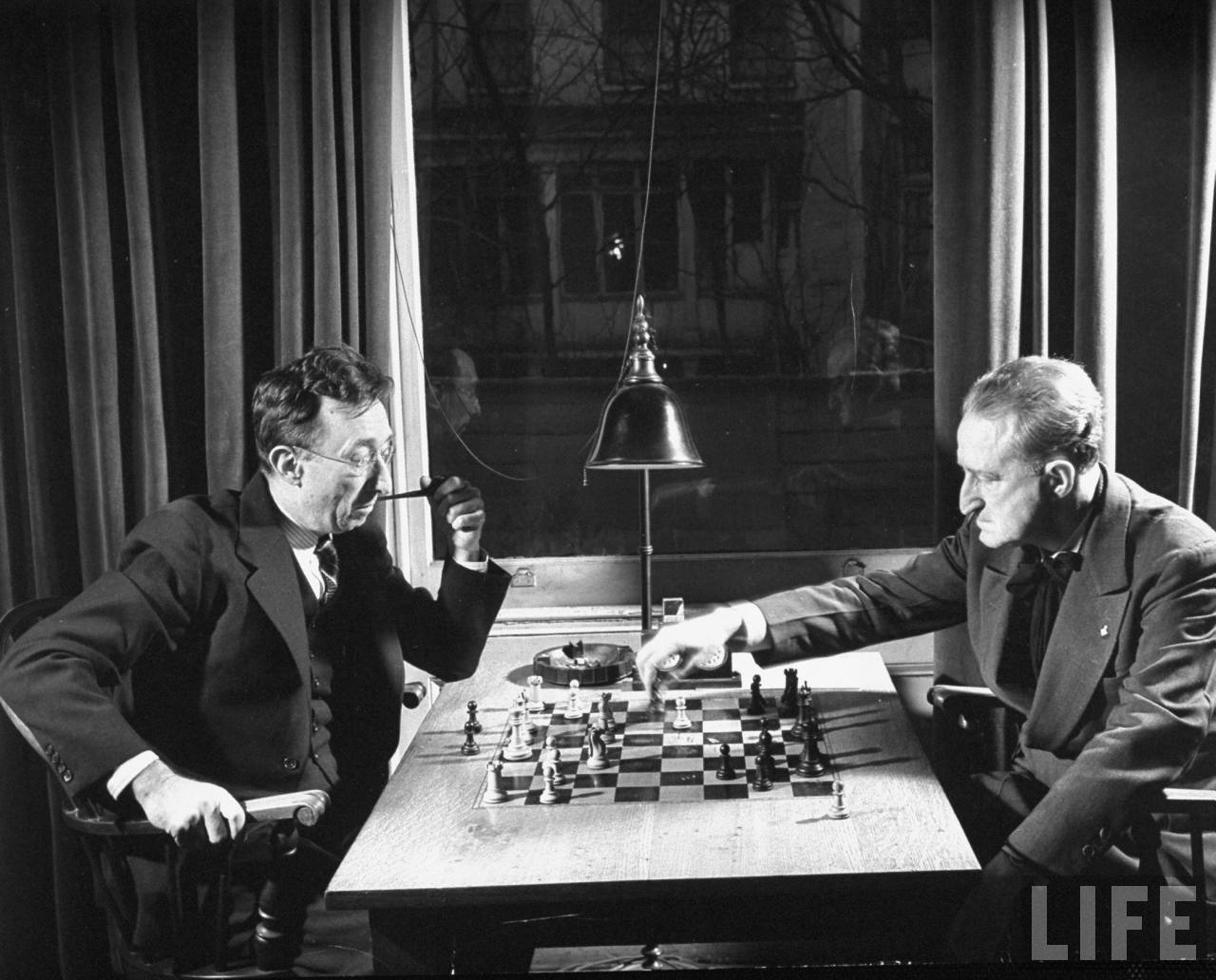

Chess Tournament

Location: US

Date taken: 1939

Photograph:

Hansel Mieth

Life Images

chess UK /

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

chess

https://www.theguardian.com/sport/

chess

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Chess

2024

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/18/

world/europe/bodhana-sivanandan-chess-prodigy-england.html

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/apr/07/

id-never-been-interested-in-chess-until-my-son-wanted-a-game

2022

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/oct/07/

the-cheating-scandal-rocking-the-chess-world

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/oct/07/

the-cheating-scandal-rocking-the-chess-world - Guardian podcast

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/

obituaries/vera-menchik-overlooked.html

2016

http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/04/23/

475125081/chess-for-progress-how-a-grandmaster-

is-using-the-game-to-teach-life-skills

http://www.npr.org/2016/02/09/

466148977/chess-wars-20-inmates-5-weeks-1-champion

2013

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/

business/for-chess-a-would-be-white-knight.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/2013/apr/01/

magnus-carlsen-chess-world-number-one

chess player USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/

us/lubomir-kavalek-dead.html

chess master USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/11/

995936257/meet-americas-newest-chess-master-10-year-old-tanitoluwa-adewumi

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/

opinion/sunday/homeless-chess-champion-tani-adewumi.html

chess prodigy UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/article/2024/aug/05/

boy-15-shreyas-royal-becomes-youngest-british-chess-grandmaster

match UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/oct/07/

the-cheating-scandal-rocking-the-chess-world

chess champion USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/

obituaries/vera-menchik-overlooked.html

chess set

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/11/20/

936732591/cant-find-a-chess-set-you-can-thank-the-queens-gambit-for-that

chess board

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/

opinion/sunday/homeless-chess-champion-tani-adewumi.html

Chess Championships UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/article/2024/aug/05/

boy-15-shreyas-royal-becomes-youngest-british-chess-grandmaster

chess grandmaster UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/article/2024/aug/05/

boy-15-shreyas-royal-becomes-youngest-british-chess-grandmaster

chess grandmaster

William James Joseph Lombardy

USA 1937-2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/14/

obituaries/william-lombardy-dead-chess-grandmaster.html

chess grandmaster

Walter Shawn Browne Australia / USA 1949-2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/

sports/walter-shawn-browne-chess-grandmaster-dies-at-66.html

Robert James "Bobby" Fischer

USA 1943-2008

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/person/bobby-fischer

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/19/

crosswords/chess/19fischer.html

Corpus of news articles

Games

> Board games > Chess

Larry Evans,

Chess Champ,

Dies at 78

November 17, 2010

The New York Times

By DYLAN LOEB McCLAIN

Larry Evans, a five-time United States chess champion and prolific writer who

helped Bobby Fischer win the world championship in 1972, died Monday in Reno,

Nev. He was 78.

Mr. Evans, who lived in Reno, died of complications of gall bladder surgery,

according to the Web site of the United States Chess Federation, the governing

body for the game.

Though Mr. Evans was a grandmaster, he was best known for his writing; he had a

syndicated chess column for decades and wrote more than 20 books, among them

“New Ideas in Chess,” “Modern Chess Brilliancies” and “The 10 Most Common Chess

Mistakes.”

Mr. Evans was an editor of the 10th edition of “Modern Chess Openings,” long a

mainstay for tournament players. He also founded American Chess Quarterly and

edited it from 1961 to 1965. The book that Mr. Evans was probably most famous

for was one on which he assisted: Mr. Fischer’s “My 60 Memorable Games.” He

cajoled and exhorted Mr. Fischer to finish the book, edited and helped him with

the prose and wrote introductions to all the games.

Typical of Mr. Evans’s style was the introduction to Game 9 against Edgar

Walther, in which Mr. Fischer escaped with a draw: “What makes this game

memorable is the demonstration it affords of the way in which a grandmaster

redeems himself after having started like a duffer; and how a weaker opponent,

after masterfully building a winning position, often lacks the technique

required to administer the coup de grace.”

During Mr. Fischer’s prelude to the world championship, Mr. Evans was what is

known in chess as his second. He helped him train and prepare for his matches

against Mark Taimanov, Bent Larsen and Tigran Petrosian. Before the championship

match in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 1972 against Boris Spassky, Mr. Evans and Mr.

Fischer had a falling out. Frank Brady, Mr. Fischer’s biographer, speculated

that the rift was over Mr. Evans’s desire to have his wife, Ingrid, accompany

them on the trip, which lasted more than two months.

Larry Melvyn Evans was born March 22, 1932, in Manhattan. Growing up, he hustled

games for dimes on 42nd Street. He won the championship of the prestigious

Marshall Chess Club on West 10th Street at 15 and was New York State champion by

18. In 1950, he played for the United States team in the biennial Chess Olympiad

in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia, and took an individual gold medal. He went on to play

on seven more Olympiad teams, including the one that won the gold medal in

Haifa, Israel, in 1976.

In 1951, at 19, he won his first United States championship. He defended the

title a year later in a match against Herman Steiner. He won the title again in

1961, 1968 and 1980, when he tied for first with Walter Browne and Larry

Christiansen. He also won four United States Open championships. The World Chess

Federation awarded him the title of grandmaster in 1957.

In the 1960s, Mr. Evans moved to Reno when he discovered he had another talent:

counting cards. “He had a memory that he built up from chess,” Dr. Brady said.

“He could memorize cards, and he wasn’t making any money from chess in those

days. Nobody was.” His other profession did not last. “He made a lot of money

and he kept getting banned from casino to casino,” Dr. Brady said.

Mr. Evans is survived by his wife, an artist and photographer, and two stepsons.

Mr. Evans had a few successes in international tournaments, among them a first

at Portimo, Portugal, in 1975. But he rarely played internationally, and in his

one attempt to qualify for the world championship, at the Amsterdam Interzonal

in 1964, he finished 14th.

Dr. Anthony Saidy, an international master who knew Mr. Evans for many years,

said the risk-taking that made Mr. Evans successful in tournaments in the United

States did not work as well against the very best players, but he was still a

formidable player. Dr. Saidy said, “He was one of the very few American

grandmasters that I couldn’t beat, ever.”

Larry Evans, Chess

Champ, Dies at 78,

NYT,

17.11.2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/

us/18evans.html

Teenage

Riddle:

Skipping Class, Mastering Chess

April 13,

2007

The New York Times

By TIMOTHY WILLIAMS

It is early

afternoon, 20 minutes into G band — or sixth period — at Edward R. Murrow High

School in Brooklyn. But today, Shawn Martinez, a third-year student, and one of

the stars of its national championship chess team, is nowhere near school.

Instead, while his classmates memorize the periodic table of the elements,

perform Shakespeare or solve for x, Shawn, wearing a black do-rag under a brown

Yankees cap, distractedly watches a pickup chess match inside the atrium of a

building on Wall Street. The place is a hangout for chess hustlers.

Shawn, 16, skips a lot of school — “It wasn’t weeks that I missed, it was

months,” he says — but he is no ordinary truant. He is so gifted a chess player

that he has claimed a place among the top young players in the nation after

learning the game only four years ago. He is also important to Murrow’s chances

of capturing its fourth consecutive national high school title; the tournament

begins today in Kansas City, Mo.

Shawn comes to Wall Street to play a type of chess called blitz, a game in which

the ticking of a three-minute clock eliminates the ponderous pauses of

traditional chess and transforms the game into a fevered, trash-talking street

sport in which money, not prestige, is the prime motivator. For Shawn, a large

bet might be $10 a game.

“It helped my game to play for money,” said Shawn, dismissing as “average” the

players he had been watching. “I love chess with a passion. It’s all the

situations you get put in — it’s like life to me. It’s like anger to me.

Sometimes, if I don’t like something that’s happening, I can take my anger out

on the chessboard.”

Murrow has no varsity sports; its nationally known chess team is a source of

deep pride at the school. And while Shawn’s story has echoes of the classic tale

of the star high school athlete who struggles academically but remains on the

team, it is also very different. Instead of marveling about quarterback options

and touchdown passes, his supporters speak about castling and checkmates. And no

one questions his intelligence.

Charming and funny, Shawn has a remarkable long-term memory, and parries easily

with older members of the Wall Street crowd as he takes their money. He is by

turns quiet and boisterous, open and defensive, and seems easily bored. He says

he does poorly in English class, but he is well spoken. During nearly three

years at Murrow, Shawn has missed so many classes that he is credited with

passing only three courses.

Administrators and the teacher who runs the club say they have struggled with

Shawn, and are seeking a balance of how to engage him in his studies without

barring him from the one thing about which he is passionate. Beth Siegel-Graf,

Murrow’s assistant vice principal for student guidance, said allowing Shawn to

compete on the team is part of a strategy intended to keep him from dropping out

altogether.

“What we try to make students and parents understand is that students doing

poorly in school are hooked to the building because of their extracurricular

activity,” she said. “We try to use that activity as a hinge.”

A math teacher named Eliot Weiss started the school on its road to becoming the

powerhouse it is today when he formed a chess club; Murrow is now able to

attract some of the city’s best young players. The team was the subject of a

recent book, “The Kings of New York,” by Michael Weinreb, an occasional

contributor to The New York Times. Two years ago, the team met President Bush in

the White House.

Shawn, like many great players, has been blessed with the combination of an

amazing visual memory and the ability to essentially see into the future by

predicting various outcomes within a few seconds. During the past two years,

Shawn has raised his United States Chess Federation rating more than 100 points

to 2,028, giving him the rank of expert, a level just below master, and ranking

him No. 19 among 16-year-olds. During that same two-year period, however, he has

flunked every class.

His relationship with chess sums up his contradictions: he loves it, yet in one

candid moment he said it had ruined his life. He had strong grades in sixth

grade, he said, but was failing in seventh — the year he started playing. And he

rejected the opinions of adults that he benefits from his relationship with the

game.

“I became addicted to chess,” he said. “They think they did something for me,

but they didn’t. Chess didn’t save my life. They want to make it like I’m a kid

from the ghetto and I can play chess and that’s special. Why does it have to be

like that? It’s embarrassing. They compare me to my environment — the way I

dress to chess. You don’t have to be the brightest person in the world to play

chess.”

Perhaps the most significant of those adults, Mr. Weiss has evolved into

something of a father figure for Shawn, whose own father died when he was young.

The teacher said he was taken aback by Shawn’s chronic underperformance.

“I have never had a student this talented in a particular skill — not just

talented, but one of the best in the country — and so disinterested in

schoolwork, not understanding what it means to fail high school,” Mr. Weiss

said.

On some days, Shawn does attend classes with about 10 other students who are

also behind. On many other days, he simply does not bother. He likes math, but

the algebra course he has been forced to take repeatedly is too easy, he said,

so he does not make an effort. “The sad thing is, some of the kids can’t even do

it,” he said.

Murrow, a 4,000-student school in the Midwood neighborhood with a far-reaching

variety of course offerings that are reminiscent of a small liberal arts

college, was founded in 1974, and it gives its students considerable freedom.

Periods are called bands. There are no bells, and no one is herded from class to

class. Free time is scheduled into every school day, and students can choose to

eat, to sleep, to do homework, to do nothing or, as Shawn has often done, to

play cards in the cafeteria.

“It is a school where if you don’t have your personal responsibility together,

you could drop out,” Shawn said.

Ms. Siegel-Graf, the assistant vice principal, said Shawn was allowed to

accompany his teammates on the plane to Missouri on Wednesday afternoon after a

conference at which he promised that, this time, he would begin going to school

regularly. Shawn turns 17 on April 24 — 11 days after the nationals start — and

Ms. Siegel-Graf said Shawn and the school had worked out an arrangement in which

although he would still be technically enrolled at Murrow, he would begin taking

courses to prepare for the G.E.D diploma.

The rules for the national tournament require students to be enrolled full time

in school in the United States or its territories for the entire semester. They

also state, “The coach is responsible for assuring that all of his players are

properly registered and eligible to participate as members of his team.”

On a recent Thursday, a few weeks before the nationals, Shawn said he had not

gone to school because he had a sore throat. Later, he said he had run out of

minutes on his mobile phone and needed to win some money playing chess to pay

the bill.

Here, among the businesspeople and tourists on Wall Street, Shawn sticks out

with his Yankees cap, baggy jeans and well-worn red and black Nike high tops,

but he also mixes easily with the stockbrokers and others who come to play.

They challenge Shawn and lose their money, even after he warns them he is an

expert.

“What I do is allow them to think they can beat me,” he said, though he denies

adamantly that he is a hustler. “It’s gambling, and gambling you do at your own

risk.”

Playing chess for money is a gray area in the law. The state statute generally

prohibits wagering on “games of chance,” but it is unclear whether chess falls

into that category. A Police Department spokesman did not respond to a request

to clarify the matter.

Shawn was taken away from his birth mother when he was one week old because of

her crack cocaine habit. Lidia Martinez, a widow who is Shawn’s adoptive mother,

said she knew immediately upon seeing the week-old Shawn that she wanted to

adopt him. Ms. Martinez acknowledged however, that she, like everyone else, had

failed to get her son to go to class. “He believes he’s too smart for school,”

she said.

Shawn says he is able to remember his biological father, who died when he was 2.

He says he can even recall his own first birthday.

At Murrow, Shawn is the third best chess player, behind the seniors Alex

Lenderman and Sal Bercys, who are each among the top 2,000 players in the world.

They were both featured prominently in Mr. Weinreb’s book, while Shawn appeared

in fewer passages. In one he is described as being “monosyllabic” and unable to

let his guard down.

“The kid’s been an enigma since junior high school,” Mr. Weinreb wrote. “He has

a gift, that much is clear, and he’s managed to discover it amid a life that has

been fraught, like so many in the city, with disappointment.”

While Alex and Sal have played since around the time they started kindergarten,

have had private coaches, and have extensive experience at tournaments, Shawn

claims to have never even cracked a chess book. “I never studied a book in my

life,” he said. “I’m too bored.” Shawn said he learns by playing, often against

opponents online. He favors an aggressive style that employs his pawns as

attackers.

“When you put pawns together, there’s no stopping them,” he said. “You put two

or three together and they practically control the whole game. People know me

for my pawns.”

Teenage Riddle: Skipping Class, Mastering Chess,

NYT,

13.4.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/13/

nyregion/13chess.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

arts > toys, games

arts

|