|

learning > grammaire anglaise - niveau avancé

séquences

nominales

syntaxe et sens

N1

+ of +

N2

sens figuré / imagé,

focalisation

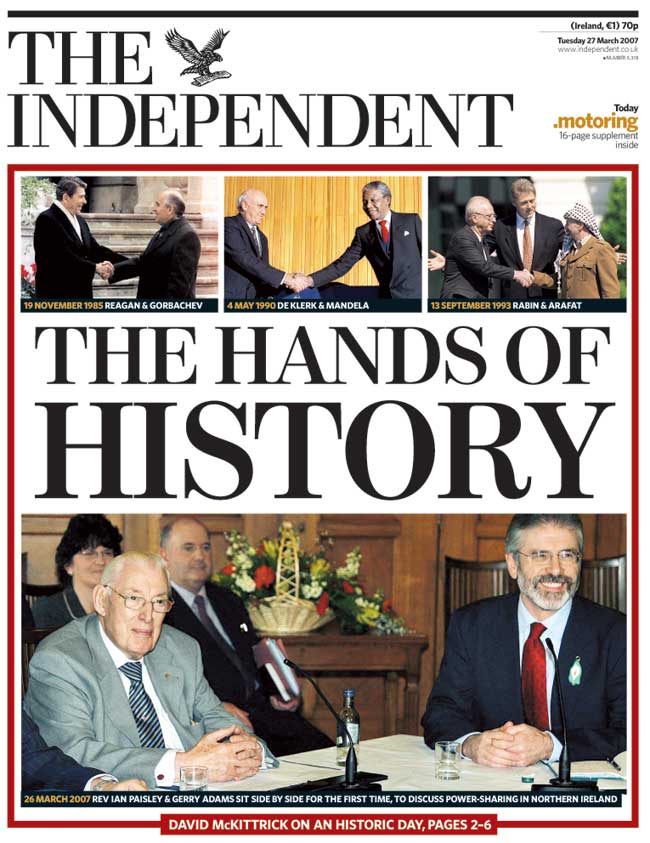

the hands of history

permutation

N2 + 's +

N1 impossible

???the history's

hands

ne fait pas sens

The hands of history:

Two worlds come together

to broker a new era of hope

David McKittrick witnesses the first meeting

between the two commanding

political figures in Belfast

as they calmly sit side by side to discuss

the

future of Northern Ireland

Published: 27 March 2007

The Independent

Ian Paisley and Gerry Adams did not shake hands yesterday: they had no need

to, since their manner of signalling they are ready to go into government

together produced an even more telling and forceful image.

The substance of what they said was breathtaking enough, but the way they did it

was even more phenomenal: they sat calmly side by side, exuding a sense of

purpose and the intention of doing serious business together.

The picture of Belfast's two commanding political figures, flanked by their

senior lieutenants, carried a subliminal but unambiguous message: after 3,700

deaths the Troubles are over and real politics can begin.

The two warriors of the Troubles believe they can work together. The statements

they delivered in the ornate surroundings of a Stormont dining-room were

exquisitely crafted to avoid giving anyone offence.

The big news they contained was that Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party

will be going into government together, launching a new era and underpinning the

peace process with a political foundation.

But even more striking was the absence of accompanying threats or conditions -

no begrudgery, no condemnations, no blame game. The two listened carefully and

politely to each other, conveying something new in Belfast politics - mutual

respect.

For many months, London, Dublin, Washington, republicans and just about everyone

else have pressed Mr Paisley to go for power-sharing with Sinn Fein. He has

finally done so, and done so handsomely, with no hint of reservation or even

tension. Until now, he has not even spoken to Mr Adams or any Sinn Fein

representative, leading some to assume that no breakthrough could be expected at

their first encounter.

But a breakthrough came and, by letting the cameras in to witness it, the

parties provided an image that will take its place among key moments in other

peace processes across the world.

Many in Belfast reacted with shock and awe: shock that the leaders of loyalism

and republicanism should have finally struck a deal, awe that it had been done

without histrionics but in such a business-like manner. Mr Paisley announced the

timetable for devolution with a phrase no one has ever heard him use before:

"Today we have agreed with Sinn Fein that this date will be Tuesday 8th May

2007." He added: "We must not allow our justified loathing of the horrors and

tragedies of the past to become a barrier to creating a better and more stable

future."

The two statements were studiously symmetrical. Mr Adams provided an echo by

accepting that "the relationships between the people of this island have been

marred by centuries of discord, conflict, hurt and tragedy." He continued: "The

discussions and agreement between our two parties shows the potential of what

can now be achieved."

The sense of mutual satisfaction was also evident in London and Dublin, with the

two governments cock-a-hoop at what they describe as the successful slotting in

of the last piece of a jigsaw that has taken a painstaking decade to put

together.

Tony Blair said proudly: "Everything we have done over the past 10 years has

been a preparation for this moment." The Irish Prime Minister, Bertie Ahern,

lauded the deal as having "the potential to transform the future of this

island."

There was also a welcome from the United States, since the Bush and especially

the Clinton administration have been closely involved in the peace process.

Washington said it looked forward to the dawning of "a new era for Northern

Ireland".

Although long anticipated, the actual accomplishment of an agreement for

government caused near-incredulity on the streets of Belfast.

The Government long ago set yesterday as a deadline, with the Northern Ireland

Secretary, Peter Hain, proclaiming - more than 50 times, by the DUP's count -

that it was "devolution or dissolution." A meeting of the Assembly set for noon

yesterday was abandoned, and the transfer of powers from London postponed until

8 May. But the loss of six weeks of devolution is regarded as a negligible price

to pay for such an advance.

Although a devolved administration was expected at some stage, until yesterday

many wondered how well it could function if Mr Paisley maintained his no-talk

stance. As First Minister he would, in particular, be expected to work alongside

Martin McGuinness, who last night accepted the post of Deputy First Minister

after being nominated by Sinn Fein. Mr Paisley has, however, now specifically

said he will have regular meetings with Mr McGuinness.

It will be fascinating to see what relationship may develop between the

Protestant patriarch and the one-time IRA commander. But if yesterday's

introductory Paisley-Adams performance is anything to go by, the expected

friction may be less than anticipated, given that the two men have spent a full

generation eyeing each other from opposite ends of the political spectrum.

Their lives have in a sense been intertwined. One of the formative political

experiences of Gerry Adams's life was a bout of serious rioting that broke out

in the Falls Road area of Belfast in 1964, when he was 16.

In his biography, Mr Adams blamed the disturbances on "a rabble-rousing,

sectarian anti-Catholic demagogue named Ian Paisley" who had threatened to

remove an Irish tricolour from the district. In the years since then, Mr Paisley

has reciprocated by describing Mr Adams with a battery of uncomplimentary names.

Those early riots pre-dated the Troubles proper, in which the loyalist and the

republican were to play prominent roles.

For decades, Mr Paisley flew a strictly fundamentalist flag, insisting that

attempts to form power-sharing governments involving Unionists and nationalists

were to be opposed at all costs. As leader of the Democratic Unionist party he

denounced Unionist leaders who sought to set up cross-community governments as

traitors, an attitude that he maintained with extraordinary consistency from the

1960s until a few years ago.

Mr Adams, as the republican movement's outstanding leader, was equally opposed

to such arrangements, though from an entirely different perspective. He held

they were diversions from the central problem, which he defined as the British

presence in Northern Ireland.

While the pair maintained those positions for decades, Mr Adams was the first of

the two to broaden his analysis and definition of the issues, seeking secret

meetings with a range of political figures and others.

By the 1990s, those efforts produced an IRA ceasefire as republicans tested the

proposition that the negative power of their violence could be replaced by entry

into politics, with votes proving more effective than guns.

This peace process, which reduced but did not remove violence, was - in its

early years - a highly controversial project, with Mr Paisley leading the ranks

of those who condemned it and wanted it closed down.

But as the death rate fell and a semblance of normality returned to Belfast, the

benefits of the process became clear. It provided huge benefits to Sinn Fein,

whose vote rose dramatically so that it has become Northern Ireland's largest

nationalist party.

The process was much more problematic for Mr Paisley, who was opposed to the

whole thing in principle and by gut instinct. But his party nonetheless accepted

posts in a power-sharing administration while refusing to attend cabinet

meetings with Sinn Fein, a stance that rivals described as "semi-detached".

Republicans have remained solidly attached to the peace process, with the IRA

eventually decommissioning its armoury and saying it was going out of business.

A key moment came when the DUP grew to become the largest Unionist party, a

position that meant Mr Paisley would get to be First Minister in any new

administration. That gave him the chance of moving on from perpetual opposition

and into powerful office.

He and his party brooded on the options for many months. Its choices were to

simply say no, thus blocking the formation of a new administration, or to agree

to take part in a coalition dominated by itself and Sinn Fein. He would be First

Minister but it would mean placing hmself at the head of a project he had spent

years condemning.

While the signs are that he decided some time ago that he would go for

devolution, a defining moment came earlier this month with elections to the

Assembly. His party scored a triumphant victory, banishing candidates who were

opposed to power-sharing.

On Saturday, a resolution supporting power-sharing was put to his party

executive and passed overwhelmingly, with some in the ranks who had seemed to be

doubters changing their position to one of support for the idea. All of that

amounted to approval for Mr Paisley going into government with a united party

and indeed a united Protestant electorate behind him, a level of support that

gave him the confidence to do business with his lifelong foes.

What happens next?

* The clock is ticking towards 8 May, the date set for the transfer of powers

from London to the Belfast Assembly. In the meantime, both Sinn Fein and the DUP

will attempt to postpone unpopular new water rates. They will also be calling on

Gordon Brown to increase a £1bn boost planned for the new administration. In the

next few days, work will also begin on a programme for government to be ready

for devolution. On 8 May, Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness are to be nominated

as First Minister and Deputy First Minister. The Assembly's four largest parties

will also nominate 10 departmental ministers.

Shaking the world

* GORBACHEV and REAGAN (19 November 1985)

After more than 40 years of nuclear brinkmanship, the two met in Geneva to talk

about scaling back their arsenals and did the unthinkable - they shook hands.

RABIN, ARAFAT and CLINTON (13 September 1993)

Bitter rivals Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shook hands at the White House. It

was the ultimate symbol of commitment to the Middle East peace process by two

men who were seen as lifelong enemies

MANDELA and DE KLERK (4 May 1990)

Mandela shook hands with the person who had come to symbolise the government

that imprisoned him. Although they remained bitter rivals, the moment came to

symbolise their commitment to South African society

NIXON and MAO (February 1972)

Setting aside two decades of bitter animosity, Nixon's surprise visit to

Communist China in 1972 and his subsequent handshake with the Chinese leader,

Mao Zedong, was described at the time as a meeting that "shook the world".

BEGIN and SADAT (26 March 1979)

The first of the Middle East's momentous handshakes, with Jimmy Carter at the

White House, sent shockwaves through the region. It ended 30 years of war

between Israel and Egypt, but led to Anwar Sadat's assassination.

The hands of history:

Two worlds come together to broker a new era of hope,

I, 27.3.2007,

http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/ulster/

article2396057.ece

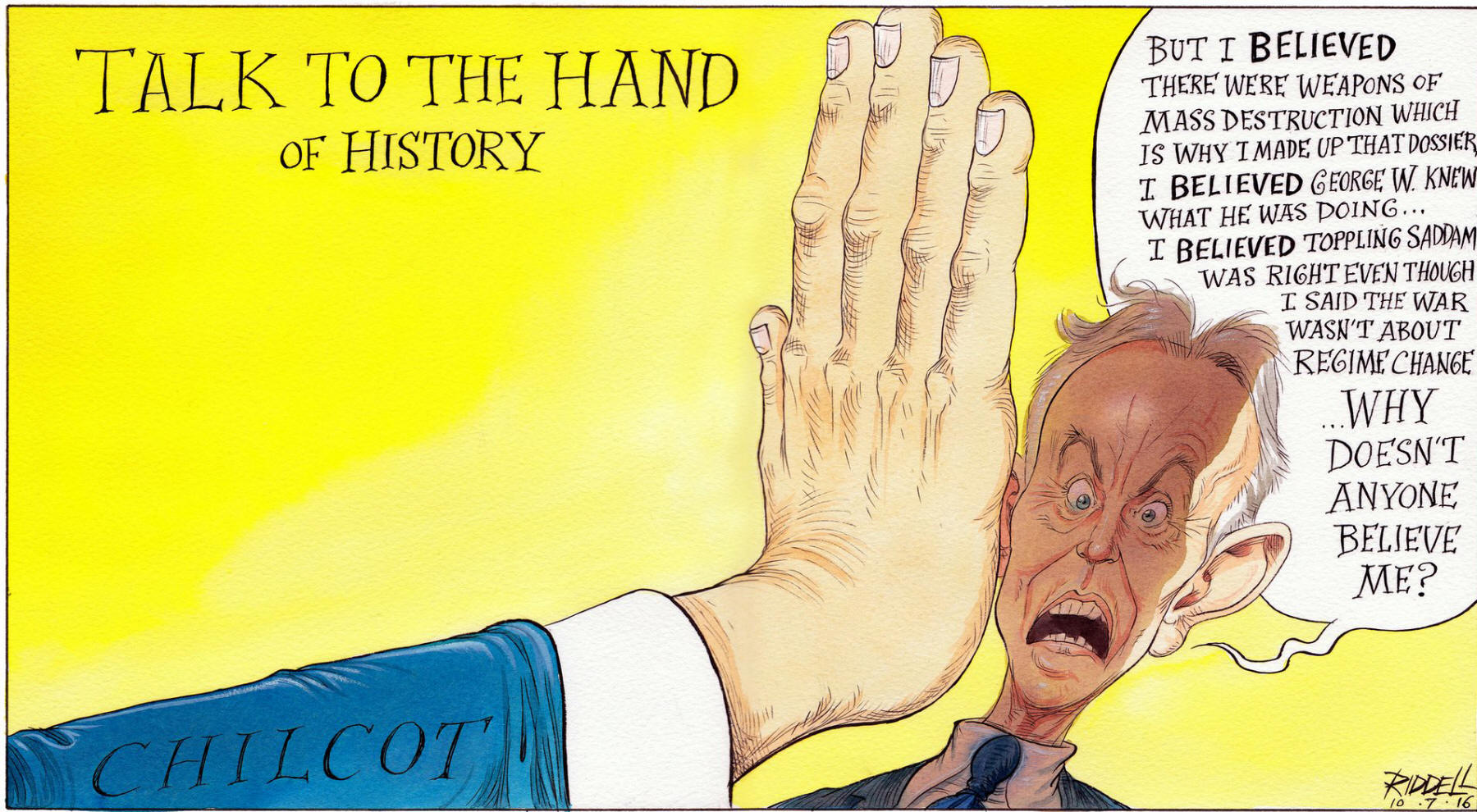

Editorial cartoon: Chris Riddell

Tony Blair and his beliefs

Chris Riddell on the former prime minister’s

response to the Chilcot report

O

Sunday 10 July 2016 00.05 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2016/jul/10/

tony-blair-and-his-beliefs

Voir aussi > Anglonautes >

Grammaire anglaise explicative - niveau avancé

N + of +

N

catégorisation >

syntaxe et sémantisme

permutation impossible

N + of + N / N +

's + N

syntaxe et sémantisme > permutation impossible

formes nominales

formes nominales > pronoms

|