|

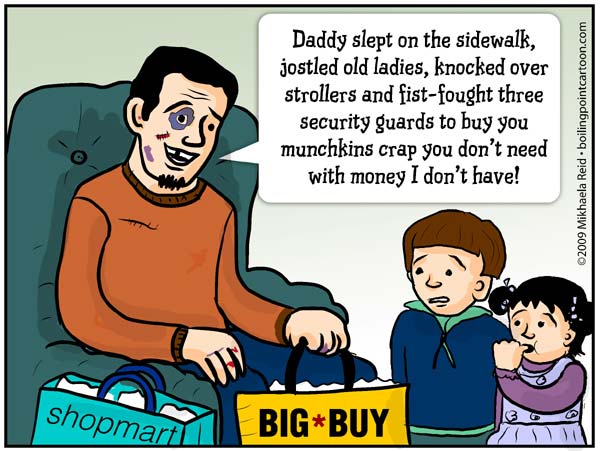

History > 2009 > USA > Economy (IX)

Mikhaela Reid

cartoon

Cagle

3 December 2009

Op-Ed Columnist

The Big Zero

December 28, 2009

The New York Times

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Maybe we knew, at some unconscious, instinctive level, that it

would be an era best forgotten. Whatever the reason, we got through the first

decade of the new millennium without ever agreeing on what to call it. The

aughts? The naughties? Whatever. (Yes, I know that strictly speaking the

millennium didn’t begin until 2001. Do we really care?)

But from an economic point of view, I’d suggest that we call the decade past the

Big Zero. It was a decade in which nothing good happened, and none of the

optimistic things we were supposed to believe turned out to be true.

It was a decade with basically zero job creation. O.K., the headline employment

number for December 2009 will be slightly higher than that for December 1999,

but only slightly. And private-sector employment has actually declined — the

first decade on record in which that happened.

It was a decade with zero economic gains for the typical family. Actually, even

at the height of the alleged “Bush boom,” in 2007, median household income

adjusted for inflation was lower than it had been in 1999. And you know what

happened next.

It was a decade of zero gains for homeowners, even if they bought early: right

now housing prices, adjusted for inflation, are roughly back to where they were

at the beginning of the decade. And for those who bought in the decade’s middle

years — when all the serious people ridiculed warnings that housing prices made

no sense, that we were in the middle of a gigantic bubble — well, I feel your

pain. Almost a quarter of all mortgages in America, and 45 percent of mortgages

in Florida, are underwater, with owners owing more than their houses are worth.

Last and least for most Americans — but a big deal for retirement accounts, not

to mention the talking heads on financial TV — it was a decade of zero gains for

stocks, even without taking inflation into account. Remember the excitement when

the Dow first topped 10,000, and best-selling books like “Dow 36,000” predicted

that the good times would just keep rolling? Well, that was back in 1999. Last

week the market closed at 10,520.

So there was a whole lot of nothing going on in measures of economic progress or

success. Funny how that happened.

For as the decade began, there was an overwhelming sense of economic

triumphalism in America’s business and political establishments, a belief that

we — more than anyone else in the world — knew what we were doing.

Let me quote from a speech that Lawrence Summers, then deputy Treasury secretary

(and now the Obama administration’s top economist), gave in 1999. “If you ask

why the American financial system succeeds,” he said, “at least my reading of

the history would be that there is no innovation more important than that of

generally accepted accounting principles: it means that every investor gets to

see information presented on a comparable basis; that there is discipline on

company managements in the way they report and monitor their activities.” And he

went on to declare that there is “an ongoing process that really is what makes

our capital market work and work as stably as it does.”

So here’s what Mr. Summers — and, to be fair, just about everyone in a

policy-making position at the time — believed in 1999: America has honest

corporate accounting; this lets investors make good decisions, and also forces

management to behave responsibly; and the result is a stable, well-functioning

financial system.

What percentage of all this turned out to be true? Zero.

What was truly impressive about the decade past, however, was our unwillingness,

as a nation, to learn from our mistakes.

Even as the dot-com bubble deflated, credulous bankers and investors began

inflating a new bubble in housing. Even after famous, admired companies like

Enron and WorldCom were revealed to have been Potemkin corporations with facades

built out of creative accounting, analysts and investors believed banks’ claims

about their own financial strength and bought into the hype about investments

they didn’t understand. Even after triggering a global economic collapse, and

having to be rescued at taxpayers’ expense, bankers wasted no time going right

back to the culture of giant bonuses and excessive leverage.

Then there are the politicians. Even now, it’s hard to get Democrats, President

Obama included, to deliver a full-throated critique of the practices that got us

into the mess we’re in. And as for the Republicans: now that their policies of

tax cuts and deregulation have led us into an economic quagmire, their

prescription for recovery is — tax cuts and deregulation.

So let’s bid a not at all fond farewell to the Big Zero — the decade in which we

achieved nothing and learned nothing. Will the next decade be better? Stay

tuned. Oh, and happy New Year.

The Big Zero,

NYT,

28.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/28/opinion/28krugman.html

Utility Bill

Is One More Casualty of Recession

December 20, 2009

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — For the Cardente family, the shutoff of

their electricity and gas in September was a wrenching marker in a two-year

downslide.

A run of mishaps, including illness and the husband’s workplace injury,

extensive structural damage from a burst water bed and the mother’s layoff from

a nursing job, had already upended their middle-class lives. Then the pile of

utility bills emerged as a headache to rival the past-due mortgage.

“You always try to pay your mortgage or rent to keep a roof over your head,”

said Debra Cardente, the mother. “Then you ask, do you pay your electric or gas

bill, pay your telephone or put food on the table?”

The recession has accentuated what was already a growing home-energy challenge

for low-income and many middle-class households across the nation. Rising

numbers have had their utilities shut off, causing desperate scrambles to pay

arrears and penalties to get them restored.

In 2009, some 31,000 households in Rhode Island will have their utilities shut

off, and the effort to juggle energy bills and mortgages is helping push some

homeowners into foreclosure, said Henry Shelton, director of the George Wiley

Center, a consumer advocacy group here. (Here, as in many states, utilities may

not disconnect the poor in the winter.)

Since 2000, the cost of heating a home with fuel oil has more than doubled and

the cost of heating a home with electricity has risen by one third, outpacing

many incomes. The recent surge in unemployment has thrown even more people into

energy debt.

Last winter, applications for federal energy assistance soared and Congress

nearly doubled money for the program, known as Liheap, to $5.1 billion. In 2009,

a record 8.1 million households, up from 6.1 million in 2008, received one-time

grants, averaging about $500, according to data released Friday by the National

Energy Assistance Directors’ Association.

Congress kept the financing at $5.1 billion for the coming year. Energy prices

have dipped slightly, but applications this fall are up an additional 20

percent, so grants will shrink or more people will be turned down, the

association said.

“Households will do just about anything to stay connected,” said John Howat, an

analyst with the National Consumer Law Center in Boston. If they cannot pay,

some people move and open a new account under a different name. Some run

extension cords from a neighbor’s house, others spend weeks getting heat from

dangerous kerosene stoves and light from candles.

The Cardentes got their power turned back on by borrowing money from relatives

and paying $3,500 toward arrears of more than $10,000. But they defaulted on a

plan that called for them to pay $723 each month, and the utility demanded the

balance of almost $5,000. They are applying for Liheap aid and plan to appeal to

the utility for more time.

For some low-income families, the federal grants have been welcome but just too

small. Suzette Orazi, 50, and her husband, Juan Lizardo, 45, live with a teenage

son in a house in Providence that is heated inefficiently with electric room

units. As energy prices climbed over the last several years, so did their

utility bills, while Mr. Lizardo lost his job as a jewel polisher.

The $1,000 they got from Liheap last winter hardly made a dent in their growing

arrears, now over $11,000. The power company recently threatened to cut them off

but later said that in accord with state protections for low-income customers,

it would not do so in winter. It is still pressing for an immediate $2,456,

however.

“We just can’t make that payment,” said Ms. Orazi, who receives disability. The

couple fears losing the house as well as the electricity needed to live in it.

California, like Rhode Island, requires lower electric rates for low-income

consumers. Even so, as unemployment in California climbed past 12 percent, the

number of shutoffs among such families rose by one-fifth in the year that ended

in August, according to a report last month by the state’s Division of Ratepayer

Advocates.

In Connecticut, the number of shutoffs for all incomes rose from 86,074 in 2008

to 105,300 in just the first nine months of 2009, according to the state’s

Public Utilities Commission.

New Jersey is widely praised for its program for low-income residents: a family

of four making less than $38,588 pays only about 6 percent of its income on

utilities. Those one step up, with incomes up to $49,612 for a family of four,

are eligible for Liheap grants.

But many families just above that level, with incomes between $50,000 and

$66,000, have found themselves in energy trouble in a high-cost state where

unemployment is 9.7 percent. New Jersey Shares, a nonprofit organization that

provides up to $1,000 in energy assistance to that group, has already helped a

record 19,000 families this fall and turned away an additional 18,000 for lack

of money, said its director, James M. Jacob. Many seeking aid are facing

imminent shutoffs, he said.

With energy costs becoming a chronic challenge, consumer advocates in Rhode

Island and elsewhere are pushing for alternatives to one-time grants, citing the

program in New Jersey and a similar one adopted this year in Illinois, setting

bills as a share of income.

Such an approach would make a world of difference for the Cardente family, for

example; in hard times, their bills would have been cut, and when Ms. Cardente

and her husband find work, the bills would rise.

New Hampshire already has income-linked subsidies, but in mid-December, citing

rising hardship, the governor and legislative leaders said they would rush

through a bill for still more aid. Indiana, Nevada, Ohio and Pennsylvania are

among states that reduce utility bills according to income levels, said Mr.

Howat, the consumer advocate.

The subsidies are usually paid for by raising rates for household, commercial

and industrial customers, posing political risks. In Rhode Island, a bill to cap

utility bills for the poor at 6 percent of income has been introduced by State

Representative Arthur Handy, Democrat of Cranston. But in a statement last June,

the state’s Division of Public Utilities and Carriers expressed “reservations”

about the proposal, and its prospects remain uncertain.

James E. Lanni, the state’s associate administrator of utilities, said the plan

would place an unreasonable burden on consumers, raising the average electric

bill by 3.7 percent and the average gas bill by 5 percent to yield $15.2 million

in subsidies. He said that the doubling of federal energy aid, along with other

programs, had reduced need and that if fees were not linked to consumption,

people would have no incentive to conserve energy.

In an interview, Mr. Handy countered that with his plan, utilities would save

money on dealing with delinquent accounts and spend less money disconnecting and

reconnecting homes.

The Rhode Island legislature is expected to consider the measure early next

year.

Utility Bill Is One

More Casualty of Recession, NYT, 20.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/20/us/20utility.html

Fed Says Economy Improving,

Though Slowly

December 17, 2009

The New York Times

By CATHERINE RAMPELL

WASHINGTON — The Federal Reserve said on Wednesday that it was

still wary of raising interest rates anytime soon because it believed the

economy, though improving, remained tenuous.

In a statement released after two days of Federal Open Market Committee

meetings, the central bank said its benchmark overnight interest rate would

remain at virtually zero, its level for the last year. The statement repeated a

pledge to keep the rate “exceptionally low” for “an extended period.”

The committee noted that economic activity, including household spending, had

continued to pick up and that the deterioration in the labor market was slowing.

Improvements in the financial markets have also become “more supportive of

growth,” the statement said.

But businesses are still cutting back on fixed investment, and employers are

still reluctant to hire.

Additionally, the Fed said that it was gradually slowing its purchases of

mortgage-backed securities and other agency debt, and that most of its emergency

liquidity programs would expire in February.

The statement comes at a time when the central bank’s response to the financial

crisis — and to its denouement — is being watched closely by traders and

politicians alike. Lawmakers have been threatening to take away some of the

bank’s supervisory powers and subject it to greater oversight.

The bank’s chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, also endured some tongue-lashings in his

reconfirmation hearings earlier this month. And the Senate Banking Committee has

scheduled a confirmation vote on Thursday morning. If the committee approves Mr.

Bernanke for a second term, his nomination will be considered by the full

Senate.

Mr. Bernanke and the Fed face a difficult balancing act in the quest to return

monetary policy to normal after two years of unprecedented intervention in the

credit markets.

If the Fed waits too long to raise interest rates and draw down its balance

sheet, it risks severe inflation. But tightening too early, or even intimating

that it could tighten soon, might spook markets and derail the recovery.

Wednesday’s release echoed the language used in the last few statements, saying

that the threat of a major increase in prices remains subdued.

Economic output grew at an annualized rate of 2.8 percent in the third quarter.

Consumer prices increased 0.4 percent at a seasonally adjusted rate in November,

according to a government report released Wednesday morning. Additionally, the

Fed’s favored barometer of inflation, a measure based on consumer spending that

excludes food and energy, has increased 1.4 percent over the last year.

November’s jobs report, which was better than expected but still showed payroll

job losses on net, has signaled that the job market may recover in the coming

months.

Despite such relatively optimistic economic news in recent weeks, Fed officials

have shown hesitation about pulling back its emergency policy measures.

“Though we have begun to see some improvement in economic activity, we still

have some way to go before we can be assured that the recovery will be

self-sustaining,” Mr. Bernanke said in a speech at the Economic Club of

Washington last week.

Mr. Bernanke is expected to be reconfirmed by Congress to serve another four

years as chairman, in spite of some vocal opposition. His current term ends Jan.

31.

In an indication of his growing popular acclaim for his handling of the crisis —

if not necessarily his leadership before the crisis — Mr. Bernanke was named

“Person of the Year” by Time Magazine on Wednesday. He has received similar

accolades in recent weeks from other magazines.

Fed Says Economy

Improving, Though Slowly, NYT, 17.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/17/business/economy/17fed.html

Obama Presses Biggest Banks

to Lend More

December 15, 2009

The New York Times

By HELENE COOPER

and ERIC DASH

WASHINGTON — President Obama pressured the heads of the

nation’s biggest banks on Monday to take “extraordinary” steps to revive lending

for small businesses and homeowners, prompting assurances from some financial

institutions that they would do more even as they continued to shed their

supplicant status in Washington.

Meeting with top executives from 12 financial institutions, Mr. Obama sent a

clear message that the industry had a responsibility to help nurse the economy

back to health and do more to create jobs in return for the huge federal bailout

last year that kept Wall Street and the banking system afloat.

But Mr. Obama also confronted the limits of his power to jawbone the industry as

banking companies continued to repay government money received in the bailout.

Citigroup and Wells Fargo, two of the biggest, announced on Monday that they

were doing precisely that.

If the banks came hat in hand to Washington a year ago to assure their survival,

they returned on Monday in a much stronger position to deal with the government.

As they scurry to repay the government and escape its influence over their

operations, they have been fighting elements of legislation to regulate their

industry more tightly.

At the same time, the banks are seeking to restore executive pay to high levels

and asserting that the government’s demand that they hold bigger financial

buffers against possible losses makes it hard for them to issue more loans.

During the hourlong meeting in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Mr. Obama

prodded the executives to stop fighting the regulation legislation intended to

deal with the problems that led to the financial crisis, White House officials

said.

“I made very clear that I have no intention of letting their lobbyists thwart

reforms necessary to protect the American people,” Mr. Obama said in remarks

after the meeting. “If they wish to fight common sense consumer protections,

that’s a fight I’m more than willing to have.”

The heads of three of the biggest companies — Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and

Citigroup — did not even make it to the White House meeting in person. They had

waited until Monday morning to travel on commercial flights to Washington and

then were held up by fog.

By contrast, James E. Rohr, PNC Financial’s chief executive, drove his own car

on Sunday evening to Washington from Pittsburgh, stopping at a Wendy’s for a

sandwich en route. Other chief executives made sure they would arrive on time:

Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase flew into Washington on one of the bank’s private

jets, while Kenneth D. Chenault of American Express took Amtrak.

Executives at the meeting said that Mr. Obama had told the missing three that he

understood that their flight had been canceled. But he directed strong words at

the industry afterward.

“America’s banks received extraordinary assistance from American taxpayers to

rebuild their industry,” Mr. Obama said. “Now that they’re back on their feet,

we expect an extraordinary commitment from them to help rebuild our economy.”

He added, “Ultimately in this country we rise and fall together; banks and small

businesses, consumers and large corporations.”

In the glare of the presidential spotlight, Bank of America used the occasion to

say it would increase lending to small and mid-size businesses by $5 billion

next year over what it lent to them in 2009. JPMorgan Chase announced a similar

increase in early November and recently experienced an increase in new

applications for loans.

Wells Fargo said in a statement on Monday that it expected to increase lending

in 2010 as much as 25 percent, to more than $16 billion, for firms with $20

million or less in annual revenue.

The banking executives promised Mr. Obama that they would take second looks at

loans they had denied over the last year. Richard K. Davis, the chief executive

of US Bancorp, told reporters after the meeting that the executives were aware

of the public perception that they were profiting with hefty bonuses at taxpayer

expense, and that they realized they were “under a microscope” and needed to

align themselves more closely with the needs of consumers.

But he cautioned that banks had a responsibility to carefully evaluate the

qualifications of each client, lest there be a repeat of the bad lending

practices that contributed to the financial crisis to begin with.

“We simply want to assure that we make qualified loans,” he said.

White House officials acknowledged that beyond the legislation on Capitol Hill,

the administration’s leverage to prod the bankers, particularly on lending, was

limited. But Robert Gibbs, the White House spokesman, said that Mr. Obama would

keep up the public pressure. “I think that the bully pulpit can be a powerful

thing,” he said.

In calling the bankers to the White House, Mr. Obama was seeking to capitalize

on public anger over the continuation of big bonuses for Wall Street executives,

coupled with the slow pace of renewed lending by institutions bailed out by

taxpayers.

During Monday’s meeting, Mr. Obama did not repeat the language he used in an

interview on “60 Minutes” on CBS Sunday night, in which he termed the bank

executives “fat cats.” During the meeting, “he didn’t call us any names,” Mr.

Davis said, adding that “we agree viscerally that more lending needs to be

done.”

But with the unemployment rate at 10 percent, the White House needs to move the

conversation from visceral to specific, administration officials said. Mr. Obama

pressed the bankers to come up with possible solutions, according to

administration officials and industry officials. In contrast to the lecturing

tones of a similar meeting last March, several people in attendance Monday

described this session as more constructive.

“There were no pitchforks, no fat cat bankers,” said Mr. Rohr of PNC.

Several of the chief executives, armed with statistics about initiatives to hire

new bankers, replied that they were very focused on lending. Some, like Mr.

Davis of US Bancorp, raised ideas like giving a second look to previously denied

loans. Others proposed cutting the red tape on Small Business Administration

loans.

Mr. Obama will meet next week with representatives of smaller banks, where he is

expected to sound similar tones.

Helene Cooper reported from Washington,

and Eric Dash from New

York.

Obama Presses Biggest

Banks to Lend More, NYT, 15.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/15/business/economy/15obama.html

Wells Fargo to Repay U.S.,

a Coda to the Bailout Era

December 15, 2009

The New York Times

By ERIC DASH and ANDREW MARTIN

When Washington pressed the nation’s largest banks to take

billions in federal support last autumn, few protested more loudly than Wells

Fargo. On Monday, Wells became the last of the big lenders to rush through a

repayment before the end of the year, signifying a fitting bookend to the

bailout era.

Hours after Citigroup confirmed it was exiting the federal Troubled Asset Relief

Program, Wells said it would return the $25 billion it was given to weather the

worst financial storm since the Depression. Wells, the largest consumer bank in

the United States, will raise $10.4 billion in a share sale to help replenish

its coffers.

Wells joins Citigroup, Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase, its largest rivals,

in shedding the stigma of taxpayer support and the restrictions on compensation

that came with it. At the same time, President Obama was pressing chief

executives of large bailed-out banks to step up lending to help an economic

recovery.

“The stigma of TARP is becoming such an emotional, testosterone-driven thing

that they want to be done with the government,” said David H. Ellison, a

portfolio manager at FBR Funds, which specializes in financial stocks. “If Bank

of America, if Citigroup can do it, then why not me, too?”

Mr. Ellison said banks appeared to be “rushing in” to pay back the government,

so they can offer bigger bonuses to their executives and get lawmakers off their

backs.

But the prospect of huge losses on mortgages and commercial real estate loans

early next year might also be causing the repayment stampede, he said.

“It may be as much about raising capital as it is paying off TARP,” he said.

While bank profits surged this year as the economy recovered and the stock

market rebounded, many banks were fearful of what next year might bring and

wanted to raise money in the capital markets now.

Although the recession has ended, high unemployment means banks like Wells and

Citigroup, which aggressively peddled consumer loans, will face looming losses

as consumers struggle to make ends meet. The stock market is also likely to

level off after a breakneck year, analysts said.

Any sudden event on the world stage, like a further weakening in emerging

markets or a sovereign default, could restrain the environment for raising

capital.

Only nine months ago, big institutional investors were so fearful during the

credit crisis that they refused to pour money into the banks that badly needed

it. Talk of nationalization prevailed.

But confidence has come back to the market, in part because the government has

shown its willingness to save large banks whose demise would produce systemic

risks after the fall of Lehman Brothers.

Yet even as banks pay back their bailout money, the government is still

extending them billions of dollars in taxpayer support through other programs

run by the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

In spite of the recent rush to repay the government, many financial experts say

the financial system is sound. At both Citigroup and Wells Fargo, regulators

required the banks to swap in private money almost dollar for dollar with the

bailout funds.

“You are talking about them having about the same amount of capital and less of

a government role, which the markets will like,” said Douglas J. Elliott, a

former investment banker and fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Even so, other financial experts worry that the government may be making a

terrible mistake by allowing the biggest banks to exit too quickly.

If the economy takes a turn for the worse, they argue, these same large banks

will return to the government for a new round of aid.

“The guarantee is no longer explicit, it’s implicit — just like the implicit

guarantee for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac,” said Dino Kos, a banking analyst and

former Federal Reserve official. “This is the nature of the ‘too big to fail’

problem.”

For the banks’ existing stockholders, repayment comes at a high cost. As part of

Citigroup’s agreement with the government, the bank is planning to raise about

$17 billion by selling stock, which will dilute the value of existing shares.

“It’s terribly negative,” said Richard Bove, an analyst at Rochdale Securities.

“Management has shown that it is willing to take any action to harm shareholders

as long as the executives get paid more money.”

Mr. Bove said the payback did nothing to improve Citigroup’s overall financial

health, nor did it remove the bank entirely from government control. Instead,

Citigroup’s management had “ruined” the stock price for the next three or four

months, he said.

On Monday, Citi’s stock lost 25 cents and closed at $3.70.

Citigroup will still operate under a loose set of pay restrictions. By contrast,

Wells will now face no pay restrictions since it will have fully repaid its

bailout funds. But that may hold less significance, because Wells, a commercial

bank, does not have the traders and bankers who demand multimillion-dollar

salaries and bonuses.

That became a sore point for Wells when Henry M. Paulson Jr., then the Treasury

secretary, summoned its chief executive to appear last October with seven others

at the Treasury Department.

At the meeting, Richard M. Kovacevich, then the Wells Fargo chairman, protested

strongly that, unlike its New York rivals, Wells was not in trouble because of

investments in exotic mortgages, and did not need a bailout, according to people

briefed on the meeting.

But Wells has since changed its tune as it struggles to digest Wachovia, which

it took over at the height of the financial crisis after a heated fight with

Citigroup. After that merger, Wells was saddled with a giant portfolio of

troubled real estate loans, and it faces a coming wave of losses on its

pick-a-pay mortgages and commercial real estate and corporate loans.

Under the terms of the deal, Wells will raise $1.35 billion by issuing common

stock to Wells benefit plans. The bank will also increase equity by $1.5 billion

through asset sales.

Wells’s current chief executive, John G. Stumpf, said the move was a good deal

for investors and taxpayers, who walk away from their investment in the bank

with a $1.4 billion dividend.

Jeff Zeleny reported from Washington,

and Eric Dash from New

York.

Wells Fargo to Repay

U.S., a Coda to the Bailout Era, NYT, 15.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/15/business/economy/15bank.html

Poll Reveals Depth and Trauma

of Joblessness in U.S.

December 15, 2009

The New York Times

By MICHAEL LUO

and MEGAN THEE-BRENAN

More than half of the nation’s unemployed workers have

borrowed money from friends or relatives since losing their jobs. An equal

number have cut back on doctor visits or medical treatments because they are out

of work.

Almost half have suffered from depression or anxiety. About 4 in 10 parents have

noticed behavioral changes in their children that they attribute to their

difficulties in finding work.

Joblessness has wreaked financial and emotional havoc on the lives of many of

those out of work, according to a New York Times/CBS News poll of unemployed

adults, causing major life changes, mental health issues and trouble maintaining

even basic necessities.

The results of the poll, which surveyed 708 unemployed adults from Dec. 5 to

Dec. 10 and has a margin of sampling error of plus or minus four percentage

points, help to lay bare the depth of the trauma experienced by millions across

the country who are out of work as the jobless rate hovers at 10 percent and, in

particular, as the ranks of the long-term unemployed soar.

Roughly half of the respondents described the recession as a hardship that had

caused fundamental changes in their lives. Generally, those who have been out of

work longer reported experiencing more acute financial and emotional effects.

“I lost my job in March, and from there on, everything went downhill,” said

Vicky Newton, 38, of Mount Pleasant, Mich., a single mother who had been a

customer-service representative in an insurance agency.

“After struggling and struggling and not being able to pay my house payments or

my other bills, I finally sucked up my pride,” she said in an interview after

the poll was conducted. “I got food stamps just to help feed my daughter.”

Over the summer, she abandoned her home in Flint, Mich., after she started

receiving foreclosure notices. She now lives 90 minutes away, in a rental house

owned by her father.

With unemployment driving foreclosures nationwide, a quarter of those polled

said they had either lost their home or been threatened with foreclosure or

eviction for not paying their mortgage or rent. About a quarter, like Ms.

Newton, have received food stamps. More than half said they had cut back on both

luxuries and necessities in their spending. Seven in 10 rated their family’s

financial situation as fairly bad or very bad.

But the impact on their lives was not limited to the difficulty in paying bills.

Almost half said unemployment had led to more conflicts or arguments with family

members and friends; 55 percent have suffered from insomnia.

“Everything gets touched,” said Colleen Klemm, 51, of North Lake, Wis., who lost

her job as a manager at a landscaping company last November. “All your

relationships are touched by it. You’re never your normal happy-go-lucky person.

Your countenance, your self-esteem goes. You think, ‘I’m not employable.’ ”

A quarter of those who experienced anxiety or depression said they had gone to

see a mental health professional. Women were significantly more likely than men

to acknowledge emotional issues.

Tammy Linville, 29, of Louisville, Ky., said she lost her job as a clerical

worker for the Census Bureau a year and a half ago. She began seeing a therapist

for depression every week through Medicaid but recently has not been able to go

because her car broke down and she cannot afford to fix it.

Her partner works at the Ford plant in the area, but his schedule has been

sporadic. They have two small children and at this point, she said, they are

“saving quarters for diapers.”

“Every time I think about money, I shut down because there is none,” Ms.

Linville said. “I get major panic attacks. I just don’t know what we’re going to

do.”

Nearly half of the adults surveyed admitted to feeling embarrassed or ashamed

most of the time or sometimes as a result of being out of work. Perhaps

unsurprisingly, given the traditional image of men as breadwinners, men were

significantly more likely than women to report feeling ashamed most of the time.

There was a pervasive sense from the poll that the American dream had been

upended for many. Nearly half of those polled said they felt in danger of

falling out of their social class, with those out of work six months or more

feeling especially vulnerable. Working-class respondents felt at risk in the

greatest numbers.

Nearly half of respondents said they did not have health insurance, with the

vast majority citing job loss as a reason, a notable finding given the tug of

war in Congress over a health care overhaul. The poll offered a glimpse of the

potential ripple effect of having no coverage. More than half characterized the

cost of basic medical care as a hardship.

Many in the ranks of the unemployed appear to be rethinking their career and

life choices. Just over 40 percent said they had moved or considered moving to

another part of the state or country where there were more jobs. More than

two-thirds of respondents had considered changing their career or field, and 44

percent of those surveyed had pursued job retraining or other educational

opportunities.

Joe Whitlow, 31, of Nashville, worked as a mechanic until a repair shop he was

running with a friend finally petered out in August. He had contemplated going

back to school before, but the potential loss in income always deterred him. Now

he is enrolled at a local community college, planning to study accounting.

“When everything went bad, not that I didn’t have a choice, but it made the

choice easier,” Mr. Whitlow said.

The poll also shed light on the formal and informal safety nets that the jobless

have relied upon. More than half said they were receiving or had received

unemployment benefits. But 61 percent of those receiving benefits said the

amount was not enough to cover basic necessities.

Meanwhile, a fifth said they had received food from a nonprofit organization or

religious institution. Among those with a working spouse, half said their spouse

had taken on additional hours or another job to help make ends meet.

Even those who have stayed employed have not escaped the recession’s bite.

According to a New York Times/CBS News nationwide poll conducted at the same

time as the poll of unemployed adults, about 3 in 10 people said that in the

past year, as a result of bad economic conditions, their pay had been cut.

In terms of casting blame for the high unemployment rate, 26 percent of

unemployed adults cited former President George W. Bush; 12 percent pointed the

finger at banks; 8 percent highlighted jobs going overseas and the same number

blamed politicians. Only 3 percent blamed President Obama.

Those out of work were split, however, on the president’s handling of job

creation, with 47 percent expressing approval and 44 percent disapproval.

Unemployed Americans are divided over what the future holds for the job market:

39 percent anticipate improvement, 36 percent expect it will stay the same, and

22 percent say it will get worse.

Marina Stefan and Dalia Sussman contributed reporting.

Poll Reveals Depth

and Trauma of Joblessness in U.S., NYT, 15.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/15/us/15poll.html

Paul A. Samuelson,

Groundbreaking Economist,

Dies at 94

December 14, 2009

The New York Times

By MICHAEL M. WEINSTEIN

Paul A. Samuelson, the first American Nobel laureate in

economics and the foremost academic economist of the 20th century, died Sunday

at his home in Belmont, Mass. He was 94.

His death was announced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which Mr.

Samuelson helped build into one of the world’s great centers of graduate

education in economics.

In receiving the Nobel Prize in 1970, Mr. Samuelson was credited with

transforming his discipline from one that ruminates about economic issues to one

that solves problems, answering questions about cause and effect with

mathematical rigor and clarity.

When economists “sit down with a piece of paper to calculate or analyze

something, you would have to say that no one was more important in providing the

tools they use and the ideas that they employ than Paul Samuelson,” said Robert

M. Solow, a fellow Nobel laureate and colleague.of Mr. Samuelson’s at M.I.T.

Mr. Samuelson attracted a brilliant roster of economists to teach or study at

the university, among them Mr. Solow as well as such other future Nobel

laureates as George A. Akerlof, Robert F. Engle III, Lawrence R. Klein, Paul

Krugman, Franco Modigliani, Robert C. Merton and Joseph E. Stiglitz.

Mr. Samuelson wrote one of the most widely used college textbooks in the history

of American education. The book, “Economics,” first published in 1948, was the

nation’s best-selling textbook for nearly 30 years. Translated into 20

languages, it was selling 50,000 copies a year a half century after it first

appeared.

“I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws — or crafts its advanced treatises — if

I can write its economics textbooks,” Mr. Samuelson said.

Histextbook taught college students how to think about economics. His technical

work — especially his discipline-shattering Ph.D. thesis, immodestly titled “The

Foundations of Economic Analysis” — taught professional economists how to ply

their trade. Between the two books, Mr. Samuelson redefined modern economics.

The textbook introduced generations of students to the revolutionary ideas of

John Maynard Keynes, the British economist who in the 1930s developed the theory

that modern market economies could become trapped in depression and would then

need a strong push from government spending or tax cuts, in addition to lenient

monetary policy, to restore them. No student would ever again rest comfortably

with the 19th-century nostrum that private markets would cure unemployment

without need of government intervention.

That lesson was reinforced in 2008, when the international economy slipped into

the steepest downturn since the Great Depression, when Keynesian economics was

born. When the Depression began, governments stood pat or made matters worse by

trying to balance fiscal budgets and erecting trade barriers. But 80 years

later, having absorbed the Keynesian preaching of Mr. Samuelson and his

followers, most industrialized countries took corrective action, raising

government spending, cutting taxes, keeping exports and imports flowing and

driving short-term interest rates to near zero.

Lessons for President Kennedy

Mr. Samuelson explained Keynesian economics to American presidents, world

leaders, members of Congress and the Federal Reserve Board, not to mention other

economists. He was a consultant to the United States Treasury, the Bureau of the

Budget and the President’s Council of Economic Advisers.

His most influential student was John F. Kennedy, whose first 40-minute class

with Mr. Samuelson, after the 1960 election, was conducted on a rock by the

beach at the family compound at Hyannis Port, Mass. Before class, there was

lunch with politicians and Cambridge intellectuals aboard a yacht offshore. “I

had expected a scrumptious meal,” Mr. Samuelson said. “We had franks and beans.”

As a member of the Kennedy campaign brain trust, Professor Samuelson headed an

economic task force for the candidate and held several private sessions on

economics with him. Many would have a bearing on decisions made during the

Kennedy administration.

Though Professor Samuelson was President Kennedy’s first choice to become

chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, he refused, on principle, to take

any government office because, he said, he did not want to put himself in a

position in which he could not say and write what he believed.

After the 1960 election, he told the young president-elect that the nation was

heading into a recession and that Mr. Kennedy should push through a tax cut to

head it off. Mr. Kennedy was shocked.

“I’ve just campaigned on a platform of fiscal responsibility and balanced

budgets and here you are telling me that the first thing I should do in office

is to cut taxes?” Professor Samuelson recalled, quoting the president.

Kennedy eventually accepted the professor’s advice and signaled his willingness

to cut taxes, but he was assassinated before he could take action. His

successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, carried out the plan, however, and the tax cut

reinvigorated the economy.

Adding a Bite to Academia

In the classroom, Mr. Samuelson was a lively, funny, articulate teacher. On

theories that he and others had developed to show links between the performance

of the stock market and the general economy, he famously said: “It is indeed

true that the stock market can forecast the business cycle. The stock market has

called nine of the last five recessions.”

His speeches and his voluminous writing had a lucidity and bite not usually

found in academic technicians. He tried to give his economic pronouncements a

“snap at the end,” he said, “like Mark Twain.” When women began complaining

about career and salary inequities, for example, he said in their defense,

“Women are men without money.”

Remarkably versatile, Mr. Samuelson reshaped academic thinking about nearly

every economic subject, from what Marx could have meant by a labor theory of

value to whether stock prices fluctuate randomly. Mathematics had already been

employed by social scientists, but Mr. Samuelson brought the discipline into the

mainstream of economic thinking, showing how to derive strong theoretical

predictions from simple mathematical assumptions.

His early work, for example, presented a unified mathematical structure for

predicting how businesses and households alike will respond to changes in

economic forces, how changes in wage rates will affect employment, and how tax

rate changes will affect tax collections.

His relentless application of mathematical analysis gave rise to an astonishing

number of groundbreaking theorems, resolving debates that had raged among

theorists for decades, if not centuries.

Early in his career, Mr. Samuelson developed the rudimentary mathematics of

business cycles with a model, called the multiplier-accelerator, that captured

the inherent tendency of market economies to fluctuate. The model showed how

markets magnify the impact of outside shocks and turn, say, an initial

one-dollar increase in foreign investment into a several-dollar increase in

total domestic income, to be followed by a decline.

The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem

Mr. Samuelson provided a mathematical structure to study the impact of trade on

different groups of consumers and workers. In a famous theorem, known as

Stolper-Samuelson, he and a co-author showed that competition from imports of

clothes and similar goods from underdeveloped countries, where producers rely on

unskilled workers, could drive down the wages of low-paid workers in

industrialized countries.

The theorem provided the intellectual scaffold for opponents of free trade. And

late in his career, Mr. Samuelson set off an intellectual commotion by pointing

out that the economy of a country like the United States could be hurt if

productivity rose among the economies with which it traded.

Yet Mr. Samuelson, like most academic economists, remained an advocate of open

trade. Trade, he taught, raises average living standards enough to allow the

workers and consumers who benefit to compensate those who suffer, and still have

some extra income left over. Protectionism would not help, but higher

productivity would.

Mr. Samuelson also formulated a theory of public goods — that is, goods that can

be provided effectively only through collective, or government, action. National

defense is one such public good. It is non-exclusive; the Navy, for example,

exists to protect every citizen. It also eliminates rivalry among its many

consumers; that is, the amount of security that any one citizen derives from the

Navy subtracts nothing from the amount of security that any other citizen

derives.

The features of public goods, Mr. Samuelson taught, stand in direct contrast to

those of ordinary goods, like apples. An apple eaten by one consumer is not

available to any other. Public goods, he concluded, cannot be sold in private

markets because individuals have no incentive to pay for them voluntarily.

Instead they hope to get a free ride off the decisions of others to make the

public goods available.

‘Correspondence Principle’

Mr. Samuelson pushed mathematical analysis to new levels of sophistication. His

“correspondence principle” showed that information about the stability or

instability of a theoretical economic system — whether, after a disruption, the

economy returns to fixed levels of prices and output or, instead, flies out of

control — could be used to predict the aggregate outcome of decisions taken by

consumers and business firms. He showed, for example, that only a stable

economic system would undergo ordinary business cycles like those captured by

Mr. Samuelson’s multiplier-accelerator model.

He analyzed the evolution of economies with a mathematical model, called an

overlapping generations model, that scholars have since used to study, for

example, the functioning over time of the Social Security System and the

management of public debt.

He also helped develop linear programming, a mathematical tool used by

corporations and central planners to calculate how to produce pre-set levels of

various goods and services at the least cost.

Late in his career, Mr. Samuelson laid out the mathematics of stock price

movements, an analysis that became the basis for Nobel-prize-winning research by

his student Mr. Merton and Myron S. Scholes. They designed formulas that Wall

Street analysts use to trade options and other complicated securities known as

derivatives.

But beyond his astonishing array of scientific theorems and conclusions, Mr.

Samuelson wedded Keynesian thought to conventional economics. He developed what

he called the Neoclassical Synthesis. The neoclassical economists in the late

19th century showed how forces of supply and demand generate equilibrium in the

market for apples, shoes and all other consumer goods and services. The standard

analysis had held that market economies, left to their own devices, gravitated

naturally toward full employment.

Economists clung to this theory even in the wake of the Depression of the 1930s.

But the need to explain the market collapse, as well as unemployment rates that

soared to 25 percent, gave rise to a contrary strain of thought associated with

Lord Keynes.

Mr. Samuelson’s resulting “synthesis” amounted to the notion that economists

could use the neoclassical apparatus to analyze economies operating near full

employment, but switch over to Keynesian analysis when the economy turned sour.

Midwestern Roots

Paul Anthony Samuelson was born on May 15, 1915 in Gary, Ind., the son of Frank

Samuelson, a pharmacist, and the former Ella Lipton. His family, he said, was

“made up of upwardly mobile Jewish immigrants from Poland who had prospered

considerably in World War I, because Gary was a brand new steel town when my

family went there.”

But after his father lost much of his money in the years after the war, the

family moved to Chicago. Young Paul attended Hyde Park High School, where as a

freshman he began studying the stock market. At one point he helped his algebra

teacher select stocks to buy in the boom of the 1920s.

“Hupp Motors and other losers,” he remembered in an interview in 1996. “Proof of

the fallibility of systems,” he explained.

He left high school at age 16 to enter the University of Chicago. “I was born as

an economist on Jan. 2, 1932,” he said. That was the day he heard his first

college lecture, on Thomas Malthus, the 18th-century British economist who

studied the relation between poverty and population growth. Hooked, he began

taking economics courses.

The University of Chicago developed the century’s leading conservative economic

theorists, under the later guidance of Milton Friedman. But Mr. Samuelson

regarded the teaching at Chicago as “schizophrenic.” This was at the height of

the Depression, and courses about the business cycle naturally talked about

unemployment, he said. But in economic-theory classes, joblessness was not

mentioned.

“The niceties of existence were not a matter of concern,” he recalled, “yet

everything around was closed down most of the time. If you lived in a

middle-class community in Chicago, children and adults came daily to the door

saying, ‘We are starving, how about a potato?’ I speak from poignant memory.”

After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Chicago in 1935, he went to Harvard,

where he was attracted to the ideas of the Harvard professor Alvin Hansen, the

leading exponent of Keynesian theory in America.

As a student at Chicago and later at Cambridge, Paul Samuelson had at first

reacted negatively to Keynes. “What I resisted most was the notion that there

could be equilibrium unemployment” — that some level of unemployment would be

impossible to eliminate and have to be tolerated. “I spent four summers of my

college career on the beach at Lake Michigan,” he explained. “It was pointless

to look for work. I didn’t even have to test the market because I had friends

who would go to 350 potential employers and not be able to get any job at all.”

Eventually he was converted. “Why do I want to refuse a paradigm that enables me

to understand the Roosevelt upturn from 1933 to 1937?” he asked himself.

A Bold Dissertation

Mr. Samuelson was perceived at the outset of his career as a brilliant

mathematical economist. He shot to academic fame as a 22-year-old l’enfant

terrible at Harvard when he began a boldly sweeping and highly technical

doctoral dissertation, published as a book in 1947 by Harvard University Press.

At Harvard, as at Chicago, he was not shy about critiquing his professors —

“respecting neither age nor rank,” according to James Tobin, a Nobel laureate of

Yale University. The young Mr. Samuelson’s chief complaint against economists

was that they preoccupied themselves with finer economic principles while all

around them people were being thrown into bread lines.

His attitudes did not endear him to the austere chairman of the economics

department at Harvard, Harold Hitchings Burbank, with whom he had a rocky

relationship.

But the publication of his dissertation was an immediate success. It won him the

John Bates Clark Medal awarded by the American Economic Association to the

economist showing the most scholarly promise before the age of 40; it would

eventually help him win his Nobel Prize, and it was frequently reprinted despite

the heavy resistance of Professor Burbank, selling to economists around the

world for more than 20 years. (“Sweet revenge,” Mr. Samuelson said.)

Among Mr. Samuelson’s fellow students was Marion Crawford. They married in 1938.

Mr. Samuelson earned his master’s degree from Harvard in 1936 and a Ph.D. in

1941. He wrote his thesis between 1937 and 1940 as a member of the prestigious

Harvard Society of Junior Fellows. In 1940, Harvard offered him an

instructorship, which he accepted, but a month later M.I.T. invited him to

become an assistant professor.

Harvard made no attempt to keep him, even though he had by then developed an

international following. Mr. Solow said of the Harvard economics department at

the time: “You could be disqualified for a job if you were either smart or

Jewish or Keynesian. So what chance did this smart, Jewish, Keynesian have?”

Indeed, American university life before World War II was anti-Semitic in a way

that hardly seemed possible later, and Harvard, along with Yale and Princeton,

was a flagrant example.

During World War II, Mr. Samuelson worked in M.I.T.’s Radiation Laboratory,

developing computers for tracking aircraft, and was a consultant for the War

Production Board. After the war, having resumed teaching, he and his wife

started a family. When she became pregnant the fourth time, she gave birth to

triplets, all boys.

Marion Samuelson died in 1978. Mr. Samuelson is survived by his second wife,

Risha Clay Samuelson; six children from his first marriage: Jane Raybould,

Margaret Crawford-Samuelson, William and the triplet sons Robert, John and Paul;

a brother, Robert Summers, a professor emeritus of economics at the University

of Pennsylvania, and 15 grandchildren.

A Keynesian Textbook

The birth of the triplets doubled the number of children in the Samuelson

household, which soon found itself sending 350 diapers to the laundry per week.

His friends suggested that Mr. Samuelson needed to write a book to earn more

money.

He decided on writing an economics textbook, but one that would not only be

compelling for students but also sophisticated and complete. And he wanted to

center it on the still poorly understood Keynesian revolution. President Herbert

Hoover, he noted, had never referred to Keynes other than as “the Marxist

Keynes.”

“I never quite understood that venom, Mr. Samuelson said.

He said he “sweated blood” writing his book, employing detailed charts, color

graphics and humor. He wrote: “Economists are said to disagree too much but in

ways that are too much alike: If eight sleep in the same bed, you can be sure

that, like Eskimos, when they turn over, they’ll all turn over together.”

It would be difficult to overestimate the influence of “Economics.” Business

Week, taking note of the textbook’s publication in Greek, Punjabi, Hebrew,

Russian, Serbo-Croatian and other languages, once said that it had “gone a long

way in giving the world a common economic language.” Students were attracted to

its lively prose and relevance to their everyday lives. Many textbook authors

began to copy its presentation.

“Economics,” together with shrewd investing, made Mr. Samuelson a millionaire

many times over.

Friendship and Rivalry With Friedman

A historian could well tell the story of 20th-century public debate over

economic policy in America through the jousting between Mr. Samuelson and Milton

Friedman, who won the Nobel prize in 1976. Mr. Samuelson said the two had almost

always disagreed with each other but had remained friends. They met in 1933 at

the University of Chicago, when Mr. Samuelson was an undergraduate and Mr.

Friedman a graduate student.

Unlike the liberal Mr. Samuelson, the conservative Mr. Friedman opposed active

government participation in most areas of the economy except national defense

and law enforcement. He thought private enterprise and competition could do

better and that government controls posed risks to individual freedoms.

Both men were fluid speakers as well as writers, and they debated often in

public forums, in testimony before congressional committees, in op-ed articles

and in columns each of them wrote for Newsweek magazine. But Professor Samuelson

said he always had fear in his heart when he prepared for combat with Professor

Friedman, a formidably engaging debater.

“If you looked at a transcript afterward, it might seem clear that you had won

the debate on points,” he said. “But somehow, with members of the audience, you

always seemed to come off as elite, and Milton seemed to have won the day.”

Mr. Samuelson said he had never regarded Keynesianism as a religion, and he

criticized some of his liberal colleagues for seeming to do so, earning himself,

late in life, the label l’enfant terrible, emeritus. The experience of nations

in the second half of the century, he said, had diminished his optimism about

the ability of government to perform miracles.

If government gets too big, and too great a portion of the nation’s income

passes through it, he said, government becomes inefficient and unresponsive to

the human needs “we do-gooders extol,” and thus risks infringing on freedoms.

But, he said, no serious political or economic thinker would reject the

fundamental Keynesian idea that a benevolent democratic government must do what

it can to avert economic trouble in areas the free markets cannot. Neither

government alone nor the markets alone, he said, could serve the public welfare

without help from the other.

As nations became locked in global competition, and as the computerization of

the workplace created daunting employment problems, he agreed with the economic

conservatives in advocating that American corporations must stay lean and

efficient and follow the general dictates of the free market.

But he warned that the harshness of the market place had to be tempered and that

corporate downsizing and the reduction of government programs “must be done with

a heart.”

Despite his celebrated accomplishments, Mr. Samuelson preached and practiced

humility. The M.I.T. economics department became famous for collegiality, in no

small part because no one else could play prima donna if Mr. Samuelson refused

the role, and, of course, he did. Economists, he told his students, as Churchill

said of political colleagues, “have much to be humble about.”

Paul A. Samuelson,

Groundbreaking Economist, Dies at 94, NYT, 14.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/14/business/economy/14samuelson.html

House Approves

Tougher Rules on Wall Street

December 12, 2009

The New York Times

By CARL HULSE

WASHINGTON — The House approved a Democratic plan on Friday to

tighten federal regulation of Wall Street and banks, advancing a far-reaching

Congressional response to the financial crisis that rocked the economy.

After three days of floor debate, the House voted 223 to 202 to approve the

measure. It would create an agency to protect consumers from abusive lending

practices, set rules for the trading of some of the sophisticated financial

instruments that fueled the crisis, and take steps to reduce the threat that the

failure of one or two huge banks or investment firms could topple the entire

economy.

Whether all of those measures will become law, however, is uncertain because the

Obama administration wants certain revisions and the Senate will not take up its

version of the legislation until next year.

The Democratic authors of the House legislation hailed the bill as the biggest

change in oversight of Wall Street since the Great Depression, and said they

believed they had struck a careful balance between protecting the public and the

economy while not stifling economic growth and market forces.

“We have a set of rules in place that will allow the most productive parts of

the free market economy, and particularly the financial system, to play the role

they should play, but with much less chance of abuse,” Representative Barney

Frank, Democrat of Massachusetts and a main architect of the measure, said after

the vote.

The approval of the bill is the most significant step lawmakers have taken to

confront the financial crisis since the $700 billion bailout package was rammed

through Congress at the peak of the emergency more than a year ago. The bill

represents an attempt to address comprehensively what many of its supporters

have called the underlying causes of the collapse — reckless risk-taking

unrestrained by regulation.

No Republican voted for the measure, and 27 Democrats, most from more

conservative districts, broke ranks with their party. Republicans strongly

criticized the Democratic legislation, saying it could restrict the availability

of credit, cause job loss and lead to future bailouts of failing businesses.

“The array of new regulations and taxes on consumers, investors and businesses

will destroy jobs and further undermine the fragile economy,” Representative

Spencer Bachus of Alabama, the senior Republican on the Financial Services

Committee, said.

The bill would create, at a cost that could run into the billions, a Consumer

Financial Protection Agency in an attempt to head off the kinds of lending

practices that led many homeowners to take on mortgages they could not afford.

The bill would bring regulation for the first time to a portion of the

over-the-counter market for derivatives. It would create a process for dealing

with troubles at very large financial institutions that might pose a risk to the

financial system and the economy, and require large firms to contribute to a

fund to help with an orderly dissolution of those institutions if they are in

danger of failing.

And the bill includes a number of other provisions to address executive

compensation, investor protections and regulation of hedge funds.

Before approving the measure, House Democrats held off an attempt led by

Representative Walt Minnick, Democrat of Idaho, to replace the proposed new

consumer protection agency with a council made up of existing regulators.

He and other moderate Democrats, joined by Republicans and much of the banking

industry, argued the new agency — a central element of the overhaul —

represented an unnecessary bureaucratic approach that would give the federal

government excessive control over mortgages, credit cards and other financial

products.

“How many new government agencies are necessary to accomplish this task?” asked

Representative Dan Boren, Democrat of Oklahoma. Their effort was defeated on a

vote of 223 to 208, removing a final obstacle to the measure.

In other important preliminary votes, lawmakers slightly scaled back the bill’s

ambitions to address objections from powerful financial interests.

Heeding complaints from banks, the House rejected an effort to allow bankruptcy

judges to restructure mortgage payments, a plan that has passed the House before

but not the Senate.

House members also agreed to relax some of the proposed new controls on trading

in derivatives. Rather than subject all over-the-counter derivatives to open

trading, the bill would subject such derivatives only if they were traded

between Wall Street firms, or with a major player like the American

International Group. But the transactions between dealers and customers will

remain largely hidden, so customers will not be able to compare the prices they

are being charged with the prices charged to other customers.

The overhaul of Wall Street regulation is a top domestic priority of the Obama

administration, which supported the House bill and applauded its approval. But

Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner signaled that the administration would

seek changes in any final measure.

Despite the House action, final legislation is not imminent. The Senate is still

developing its own measure for debate early next year and any Senate bill is

likely to differ substantially from the House measure, necessitating further

negotiations.

Most Democrats agreed that stiffened regulation of the financial services

industry was warranted by the events leading up to the financial crisis.

Representative Steny H. Hoyer of Maryland, the House majority leader, cited what

many considered a lack of adequate regulation during the administration of

President George W. Bush as a central reason for the economic collapse.

“This bill puts the referees back on the field,” Mr. Hoyer said.

The chief argument in the House centered on the Democratic proposal that would

assess large financial companies a fee to create a $150 billion fund to cover

the costs of dissolving companies that pose a threat to the economy.

Democrats said the fund did not amount to a reserve for bailouts since it would

not be used to keep companies afloat but would instead lead to a more orderly

shutdown and would be paid for by large companies, not taxpayers.

Republicans, trying to capitalize on public frustration with financial bailouts,

said that failing firms should instead go through normal bankruptcy proceedings.

“We just think at the end of the day that $150 billion in a permanent bailout

fund is not the direction the American people want this nation to go,” said

Representative Mike Pence of Indiana, the No. 3 Republican in the House.

Both sides saw the vote as a political opening in the coming midterm elections.

Republicans sought to turn the issue on dozens of potentially vulnerable

Democrats in swing districts, noting that they had opposed a Republican

procedural move that would have shut down the bailout fund and put the money

toward paying off the national debt.

Floyd Norris contributed reporting from New York.

House Approves

Tougher Rules on Wall Street, NYT, 12.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/12/business/12regulate.html

Op-Ed Columnist

An Innovation Agenda

December 8, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

The economy seems to be stabilizing, and this has prompted a

shift in the public mood. Raw fear has given way to anxiety that the recovery

will be feeble and drab. Companies are hoarding cash. Banks aren’t lending to

small businesses. Private research spending is drifting downward.

People are asking anxious questions about America’s future. Will it take years

before the animal spirits revive? Can the economy rebalance so that it relies

less on consumption and debt and more on innovation and export? Have we entered

a period of relative decline?

The first thing to say is, let’s not get carried away with the malaise. The U.S.

remains the world’s most competitive economy, the leader in information

technology, biotechnology and nearly every cutting-edge sector.

The American model remains an impressive growth engine, even allowing for the

debt-fueled bubble. The U.S. economy grew by 63 percent between 1991 and 2009,

compared with 35 percent for France, 22 percent for Germany and 16 percent for

Japan over the same period. In 1975, the U.S. accounted for 26.3 percent of

world G.D.P. Today, after the rise of the Asian tigers, the U.S. actually

accounts for a slightly higher share of world output: 26.7 percent.

The U.S. has its problems, but Americans would be crazy to trade their problems

with those of any other large nation.

Moreover, there’s a straightforward way to revive innovation. In an unfairly

neglected white paper on the subject, President Obama’s National Economic

Council argued that the U.S. should not be in the industrial policy business.

Governments that try to pick winners “too often end up wasting resources and

stifling rather than promoting innovation.” But there are several things the

government can do to improve the economic ecology. If you begin with that

framework, you can quickly come up with a bipartisan innovation agenda.

First, push hard to fulfill the Obama administration’s education reforms. Those

reforms, embraced by Republicans and Democrats, encourage charter school

innovation, improve teacher quality, support community colleges and simplify

finances for college students and war veterans. That’s the surest way to improve

human capital.

Second, pay for basic research. Federal research money has been astonishingly

productive, leading to DNA sequencing, semiconductors, lasers and many other

technologies. Yet this financing has slipped, especially in physics, math and

engineering. Overall research-and-development funding has slipped, too. The U.S.

should aim to spend 3 percent of G.D.P. on research, as it did in the 1960s.

Third, rebuild the nation’s infrastructure. Abraham Lincoln spent the first half

of his career promoting canals and railroads. Today, the updated needs are just

as great, and there’s widespread agreement that decisions should be made by a

National Infrastructure Bank, not pork-seeking politicians.

Fourth, find a fiscal exit strategy. If the deficits continue to surge, interest

payments on the debt will be stifling. More important, the mounting deficits

destroy confidence by sending the message that the American government is

dysfunctional. The only way to realistically fix this problem is to appoint a

binding commission, already supported by Republicans and Democrats, which would

create a roadmap toward fiscal responsibility and then allow the Congress to

vote on it, up or down.

Fifth, gradually address global imbalances. American consumers are now spending

less and saving more. But the world economy will be out of whack if the Chinese

continue to consume too little. The only solution is slow diplomacy to rebalance

exchange rates and other distorting policies.

Sixth, loosen the so-called H-1B visa quotas to attract skilled immigrants.

Seventh, encourage regional innovation clusters. Innovation doesn’t happen at

the national level. It happens within hot spots — places where hordes of

entrepreneurs gather to compete, meet face to face, pollinate ideas. Regional

authorities can’t innovate themselves, but they can encourage those who do to

cluster.

Eighth, lower the corporate tax rate so it matches international norms.

Ninth, don’t be stupid. Don’t make labor markets rigid. Don’t pick trade fights

with the Chinese. Don’t get infatuated with research tax credits and other

gimmicks, which don’t increase overall research-and-development spending but

just increase the salaries of the people who would be doing it anyway.

This sort of agenda doesn’t rely on politicians who think they can predict the

next new thing. Nor does it mean merely letting the market go its own way. (The

market seems to have a preference for useless financial instruments and insane

compensation packages.)

Instead, it’s an agenda that would steer and spark innovation without

controlling it, which is what government has done since the days of Alexander

Hamilton. It’s the sort of thing the country does periodically, each time we

need to recover from one of our binges of national stupidity.

An Innovation Agenda, NYT, 8.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/08/opinion/08brooks.html

AP: Manufacturing Areas

Lead Surprise Job Comeback

December 6, 2009

Filed at 3:33 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

CONOVER, N.C. (AP) -- As record numbers of orders flow through

Legacy Furniture Group's manufacturing plant, workers toil between towers of

piled foam and incomplete end tables precariously stacked five pieces high.

With a 10 percent sales growth this year, Legacy has quickly forgotten the

recession's low point in March, when weak order volumes forced the company to

implement four-day work weeks.

In November alone, the company that specializes in furniture for the medical

industry added a half-dozen employees to its staff of 35. These days, everyone

is clocking overtime and the 40,000-square-foot factory is starting to feel

awfully cramped.

''We're starting to stack people instead of stacking furniture,'' jokes

co-founder Todd Norris as he navigates rows of hand-sanded chair frames.

Legacy's recent success highlights a trend: Counties with the heaviest reliance

on manufacturing income are posting some of the biggest employment gains of the

nation's early economic recovery. This is a big change from just half a year

ago, when some economists worried that widespread layoffs by U.S. manufacturers

might be part of an irreversible trend in that sector.

The Associated Press Economic Stress Index, a monthly analysis of the economic

state of more than 3,100 U.S. counties, found that manufacturing counties have

outperformed the national average since March. The Stress Index calculates a

score from 1 to 100 based on a county's unemployment, foreclosure and bankruptcy

rates. The higher the number, the greater the county's level of economic stress.

The top 100 manufacturing counties with populations of more than 25,000 saw

their Stress score drop slightly over the spring and summer quarters, largely

due to improvements in the unemployment rate. By comparison, the national

average of similar counties saw county Stress score increases of about 7 percent

over the same time.

Economists say these counties may always have high rates of idled workers as

technology replaces workers on the assembly line and companies find cheaper

labor elsewhere. And manufacturing counties did have an average Stress score of

11.9 in September, while the top counties dedicated to hospitality were at 9.2.

But the early improvements in unemployment rates and manufacturing activity

illustrate that there are, at the very least, signs of stability. U.S.

manufacturers increased production by an average of 1.1 percent each month

through July, August and September, before falling slightly, by 0.1 percent, in

October, according to federal data.

Economists cite a range of potential explanations for the early resurgence,