|

History > 2009 > USA > Health (VII)

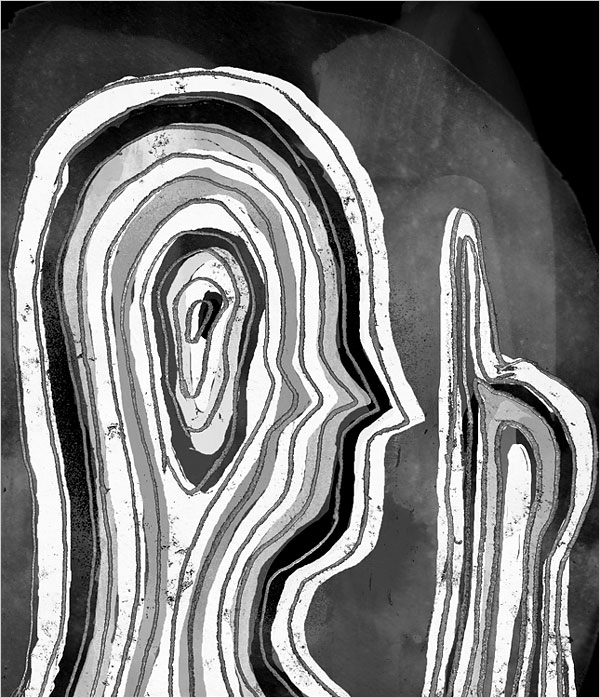

Illustration: Jon Han

How Biology Influences Our Behavior

NYT

15.10.2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/15/

opinion/l15brooks.html

Editorial

A Modest Public Plan

November 29, 2009

The New York Times

It is astonishing, but the question of whether a small slice

of Americans should be able to choose between a government-run health insurance

plan and private health insurance plans is threatening passage of much-needed

health care reform.

Senate Democrats barely mustered enough votes to start debating their reform

bill, and some senators who voted to allow debate have said flatly that they

will not support the final bill if it retains its public option clauses. If they

mean what they say, their defection could make it extremely hard to overcome a

Republican-led filibuster.

We got to this juncture because, in an already overheated political debate, no

issue has drawn more demagoguery and less rational analysis than the public

option. And while both political parties exaggerate what a public plan could do,

Republican critics are particularly divorced from reality.

They say the public option would start a government takeover of all health care;

interpose government bureaucrats between patients and their doctors; sound the

death knell for private insurance; and lead many companies to dump insurance

benefits. They also say it could cost taxpayers a lot.

Democrats, meanwhile, claim that competition from a public plan would help drive

down insurance premiums and the overall cost of medical care.

We wish the proposed public plan could be powerful enough to demand low rates

from health care providers, charge much lower premiums than private plans and

attract large numbers of enrollees. But neither the House nor Senate versions

would have that kind of power.

Here is what a public option — as structured in the House and Senate bills —

would do and would not do:

HOW IT WOULD WORK Both bills would create new insurance exchanges, with an array

of plans to choose from, for a limited number of Americans — those who lack

group coverage and must buy policies directly from insurers and those who work

for small employers, about 30 million people within a few years. With millions

of potential new clients, all major insurers are expected to participate. And

Congress willing, a new public plan would also be available.

The government would run the public plan, but both the Senate and House versions

would require it to compete on a “level playing field.” It would have to follow

the same rules as the private plans, meet the same benefit standards, maintain

the same reserves, and support itself entirely with premium income, with no

federal help beyond start-up money that would have to be repaid.

The secretary of health and human services, as the head of the plan, would have

to negotiate rates with health care providers just as the private plans do.

WHAT IT COULDN’T DO Because of intense opposition from conservatives, both bills

shunned a more robust public plan that would have had the power to virtually

force doctors to serve its beneficiaries — at Medicare rates that are typically

less than private plans pay them.

As a result, the current weaker versions could find it difficult to compete with

well-entrenched private insurers. The Congressional Budget Office believes

public plan premiums would actually end up higher than the average private plan

premium. This is partly because the public plan would probably attract the

sickest patients, whose bills are highest, and who might fear that private plans

would find some way to jettison them.

All told, the C.B.O. estimates that the House bill’s public plan would attract

only six million enrollees. The Senate version, which would allow states to opt

out, might attract only three million to four million.

This is not going to destroy the private insurance market or start a government

takeover of the health care system, or put bureaucrats in control, any more than

private plans do. Nevertheless, in a recent Senate debate, Republicans insisted

that more than 100 million Americans might enroll in a public plan, the vast

majority of them dumped by employers from coverage that they were satisfied

with.

That overblown claim is based on a study showing that a much more robust plan

could offer far lower premiums than private plans, and if available to virtually

everyone, it could attract huge numbers of enrollees.

In that no-longer-relevant scenario, private plans would indeed lose a lot of

their subscribers. But workers would still not lose their employer-sponsored

benefits. Their employer’s subsidy would follow them to the exchanges, where

they would have a much wider choice of plans than they now do. Even in a

nightmare scenario that lives only in Republicans’ fevered rhetoric, workers

would be better off than they now are.

Although the public plan is supposed to be self-sustaining, critics worry that

if it starts to fail, future Congresses will bail it out with taxpayer money. We

hope they are wrong. If the public plan gets into financial trouble, it should

simply raise its premiums or close.

SO IS IT STILL WORTH DOING? Even with the constraints, a public plan could be a

useful part of health care reform. Most important, it would compete in markets

dominated by one or two private insurers that can charge more and not worry

about losing customers.

The presence of a public plan could serve as a brake on unwarranted premium

increases by the private companies. The C.B.O. said a public plan with

negotiated rates would place “downward pressure on the premiums of private

plans.” A public plan would also provide a safe harbor for people who do not

trust the insurance industry and would prefer a government plan even if its

premiums were higher. And it would be a place to test innovative ideas for

controlling costs and improving quality.

The C.B.O., a notably cautious evaluator, could be wrong in its assessments. The

plan might turn out to be better at negotiating lower rates. And with no need to

turn a profit, it might be able to charge less than private plans and attract

millions more people than expected. That could force private plans to lower

their own rates.

We are not holding our breath. The public plan could face enormous practical

problems entering markets where private insurers already have well-established

networks of providers or where hospital groups already have the upper hand in

negotiating with insurers.

Even a weak public plan would be better than no public plan. It would expand the

choices available to millions of Americans and could help slow the relentless

increases in the cost of health insurance. Congress certainly owes Americans a

more rational and informed debate.

•

This editorial is a part of a continuing series by The New York Times that is

providing a comprehensive examination of the policy changes and politics behind

the debate over health care reform.

A Modest Public Plan,

NYT, 29.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/29/opinion/29sun1.html

The Cancer Lounge

November 29, 2009

The New York Times

By N. R. KLEINFIELD

The cancer patient racked them up and broke. Clackety-clack. Seven ball in

the corner pocket. Five ball in the side.

Light was seeping out of day. The long, brick-walled room was getting busy.

People hooked to IVs in whispered conversation. Others working a jigsaw puzzle.

Playing gin rummy. All of them caught in an unwelcome dance with mortality.

This is what passes for pleasure in a cancer hospital.

Paul Gugliotta always sought out the pool table. His game had sharpened beyond

expectations. Since a diagnosis of lymphoma in June, Mr. Gugliotta, a chemical

engineer from Long Island, had had two lengthy stays at Memorial Sloan-Kettering

Cancer Center on the Upper East Side. He chafed at being cooped up in his

antiseptic room. He even fled the grounds several times, in violation of the

rules, wandering down to the 59th Street Bridge and ordering a hot open-faced

turkey sandwich at a nearby diner. Then one day he stumbled upon the recreation

center, which can be reached from the hospital’s 15th floor, and it became his

nesting ground.

It is something of a cancer patient’s corner bar, minus the booze. Mr. Gugliotta

hung around and talked cancer, talked life. He sampled just about everything the

center offered. Pottery, copper enameling, blackjack. He made a toolbox, a

stained-glass thermometer. His wife, Francine, said, “I never thought I’d see

him doing decoupage, but sure enough.”

Now, Mr. Gugliotta, 46, is a commuter, reporting every three weeks for

chemotherapy. While the chemicals are mixed, a process that can make patients

wait up to two hours, he repairs to the recreation center and begins

methodically rocketing balls into pockets. He knows the good cue is stashed in

the back. “It’s enjoyable here,” he said. “And it’s where you can talk about

what’s inside you, because it’s inside everyone here.”

Nothing about this big room will cure what brings its visitors to

Sloan-Kettering. Distraction from the truths and riddles of the vile disease

they have, though, is sometimes good enough, a counterpoint to the scientific

experiments that fill the rest of the hospital, and to the claustrophobia of

their thoughts. It’s a place to have some fun within a building where it’s hard

for many who enter to imagine fun.

Putting Fear in Its Place

Recreation centers are staples of nursing homes and pediatric wards, but are

unusual in general hospitals for adults. But since Sloan-Kettering is a cancer

hospital, patients typically stay a while — the average is six days, and many

are there for weeks or even months at a stretch — then return repeatedly as

outpatients.

“There is a lot of down time with nothing to do,” said Yolanda Toth, the adult

recreation center’s director. “After you’ve counted all the holes in the ceiling

of your room and all the blocks and watched enough television, you’re pretty

bored. And then you start thinking — what’s going to happen to me?”

Patients can avoid those crushing fears, or confront them, at the center, open

daily from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. The sprawling room, its walls adorned with patient

art, contains a pool table, a foosball table, a movie screen, a sitting area and

tables for scheduled craft workshops; adjoining it is a terrace with commanding

views. Visiting performers appear — comedians, Juilliard students. The library

is braced with 12,000 volumes, including plenty of paperbacks; hardcover

editions are too heavy for some of the patients.

Doctors or nurses are not allowed in the recreation center. It’s the No White

Coats Rule. If they need to see a patient, they call and the person is sent back

to their room. “Sometimes doctors will wander in and we will very politely tell

them to wander out,” Ms. Toth said.

In a 434-bed hospital, the recreation center got roughly 35,000 visits last

year, including from outpatients and family members. At the start of a week,

when new patients tend to be admitted, only a few dribble in. Other times,

several dozen people populate the place.

Many patients are too weak or straitened by grief to come by, or don’t see the

point. Others glide into the center in wheelchairs, even on stretchers. Many pad

in rolling IV poles, the dangling drip bags working on their cancer even as they

make rag dolls or play cards.

All in the Cards

Texas Hold ’em was Monday evening. Just three patients showed, so the dealer,

another volunteer and a visitor joined in. No money changed hands. But there

would be prizes.

Douglas Meyers dealt the requisite two cards, accepted bets, turned over the

flop. He is 26, a technology project manager at Citibank, who volunteers to deal

poker hands. Cancer runs in his family — his mother died of melanoma — and that

connection got him engaged.

The weekly poker game commenced in June (before that Mr. Meyers presided over

the roulette wheel). Beginners are welcome. Not long ago, though, a former

participant in the World Series of Poker landed in the hospital. He sat down and

did quite well indeed.

On this Monday, Lee Piepho, 67, was fumbling his way through the hands. An

English professor at Sweet Briar College in Virginia, he was in the hospital to

address an infection after having had surgery for a soft-tissue sarcoma. And he

was rusty. Back in 1958, when he was 16, Mr. Piepho lost $25 in a Chicago poker

game, had to nervously explain the sour outcome to his father and abandoned

cards. But now this.

Unsure of his instincts, he folded successive hands, then raked in one big pot

with a straight, snatched another with two pairs. A young woman shuffled by with

her IV trolley, a scarf masking her baldness, and she smiled on his good

fortune. Besides cards, Mr. Piepho had been using the center’s library, caught

part of the Alfred Hitchcock film “Notorious” the other day, played Speed

Scrabble.

He felt comfortable in the center. Among other things, it allowed his cancer to

be out front, because it was everywhere in the room. It is those without cancer

who felt strange here.

Outside of the hospital, Mr. Piepho rarely speaks of his condition, even to

close friends. “I think there’s a certain ethical responsibility about handling

cancer,” he said. “There’s a burden you place on people when you tell them you

have it. Here there’s no burden. This particular place is common ground.”

Nursing a decent stack of chips, Mr. Piepho played the remaining hands warily,

folding miserable cards early. He wound up the winner with a chip count of 19,

eclipsing a 68-year-old woman who had had surgery for uterine cancer and now

seemed to have a growth in her lungs.

Mr. Piepho collected his prize: a green Brooks Brothers tie.

Oil Painting Is Out

The recreation idea at Sloan-Kettering goes back to 1947, and in the early years

the department functioned out of two small second-floor rooms, ferrying

activities throughout the hospital. There were some art classes, sewing circles

and a little music. A spinet piano was wheeled clumsily from floor to floor.

Two years after Sloan-Kettering opened its new building in 1973, the recreation

department earned an entire floor of the old adjoining structure, where it

remains. The scope of activities broadened enormously. The place was renovated

with a gift from the estate of Abby Rockefeller Mauzé, and is paid for out of

the hospital’s operating budget.

Strong odors are avoided, since patients in chemotherapy can develop severe

headaches or nausea from potent smells. Therefore, no oil paints. Only stems

with mild scents are chosen for the flower-arranging sessions. Busy patterns can

make patients dizzy, so solid-colored carpeting and simple tile adorn the floor.

Ms. Toth has years of quirky episodes to recount. A man from Florida was

admitted for throat cancer surgery. His parents came up from Maryland to sit at

his bedside. Eventually, they began to gnaw at his nerves. He told Ms. Toth that

they were jigsaw puzzle nuts. Could she dig up the toughest puzzle she had and

get them going on it? She fished out a monster with 1,500 pieces and a fiendish

pattern. They spent days attacking it, affording their son the peace he craved.

Six years ago, the mother of a soon-to-be bride was a patient, not doing very

well, and the family feared she might not make the wedding. They moved up the

date and held the ceremony at the recreation center. A justice of the peace

presided. Ms. Toth made the wedding cake.

On New Year’s Eve, the center stays open until 1 a.m. Last year, there was

nonalcoholic Champagne and belly dancers. They’re coming again this year.

A Tough Crowd

Maury Fogel said, “Hi, did I wake you?”

He said, “Ever go to the eye doctor and get these magazines with small print? I

can’t see, Doc! You get new glasses — it costs you 500 bucks.”

O.K.

The comedians come twice a month. The rules are: no vulgarity, no death jokes,

no cancer jokes, no edgy medical jokes. Mr. Fogel, a messenger who moonlights as

a stand-up comedian, puts the bill together. On this night, there was an

audience of 14.

Billy Bingo came on. He promotes himself as New York’s Bravest Comic, because he

used to be a firefighter. Mr. Bingo said: “People say I look like Sonny Bono.

What do you think? I usually get, ‘After the tree.’ ”

He said: “We had a fire in a massage parlor. You want to talk about a fast

response! I was already there.”

Some chuckles, an occasional deep-throated laugh. Tough crowd.

Earlier, the “Look Good ... Feel Better” program for women had 10 patients

clustered around a square table gazing into makeup mirrors. “We don’t talk about

doctors or appointments,” Penny Worth, a former Broadway performer and the

program’s coordinator, told them. “We get away from that. Be girls.”

The concept: Teach cancer patients to use makeup and wigs to improve their looks

and their spirits. Hence, sharpen eyebrow pencils every day when going through

treatment. Wash wigs after six to eight wearings in spring and summer, 12 to 15

in fall and winter.

Afterward, Ms. Worth and the volunteers broke into the old ragtime song “Oh, You

Beautiful Doll.”

Josephine Walsh was circling the room. She’s a veteran. She is 84, and has been

coming to the recreation center for 22 years from her home in Queens. First she

had cancer in a kidney, then breast cancer, and now she is an outpatient. She

watched a daughter die of lung cancer at 40.

“My whole life is seeing doctors, trust me,” Ms. Walsh said. She shows up at

least once a week, likes to make jewelry, talk to whoever is around. “I ask them

where their boo-boo is,” she said. “It’s easy to talk with someone who lives in

the same shoes.”

She looked on as a woman from Florida with rectal and lung cancer pasted leaves

into a collage, something achieved. The woman inhaled deeply, feeling a little

woozy.

Ms. Walsh told her: “You forget all your troubles when you’re in here.”

She told her: “You’ll be well. God bless you.”

The Would-Be Olympian

Stories take hold in the recreation center for moments in time, then relocate,

overtaken by new ones. Happy stories, sad stories.

For weeks, one of the odder sights had been the genial young man, usually

connected to the IV pole he had nicknamed Bertha, on the terrace doing the

regimen he devised: 1,000 jumping jacks, 250 push-ups, 500 situps, 400 lunges.

He was training to represent Nigeria in the Olympics in the skeleton, a sledding

event.

He was aiming for the 2014 Olympic Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. Nigeria has

never sent anyone to the Winter Games in the skeleton. Nigeria has never sent

anyone to the Winter Games in anything. And he had never tried the skeleton.

The man’s name is Seun Adebiyi. He is 26. Born in Nigeria, he moved to Alabama

with his mother, a math professor, when he was 6. In May, he graduated from Yale

Law School. He is on leave from his job as an operations analyst with Goldman

Sachs in Salt Lake City. Salt Lake City happens to be one of two places in the

country with a facility to practice skeleton. You lie on your stomach and ride

the sled at absurd speeds down a twisting course.

Early next year, Mr. Adebiyi intends to take the New York bar exam. Eventually,

he hopes to return to Nigeria and try to make the country better. In addition to

his workouts, he has been studying for the bar in the center, in jeans and a

T-shirt. “I continue to think of me as I was before I came here,” he said.

“Wearing the hospital gown is like a form of surrender I’m not willing to do

yet.”

Mr. Adebiyi said that he had felt since he was little that he ought to be in the

Olympics. For years, he swam competitively. He missed qualifying for the 2004

Summer Games by a tenth of a second in the 50-meter freestyle. The slim miss

sent him into a funk.

Last March, he researched alternate events that would be less competitive in

Nigeria. Well, winter sports aren’t big in a country without any actual winter.

Skeleton seemed the ticket. He had never been on a sled, but so what.

Then in June a swelling he had noticed in his groin led him to find out he had

lymphoblastic lymphoma and stem-cell leukemia, two rare and aggressive cancers.

As Mr. Adebiyi put it, “It completely reshuffled the deck.”

This was his seventh week at Sloan-Kettering. Chemotherapy had contained things

for now. Yet he urgently needed a bone marrow transplant. He has no full

siblings. Available donors are sparse for people of African descent. A good

donor has not yet been found.

Mr. Adebiyi dealt with the unknown through daily meditation. He began a blog,

nigeria2014.wordpress.com, in part to advocate for minority donors, to help

others if he can’t help himself.

He liked it at the recreation center. “When you talk about your cancer, you

don’t get the intake of breath, the sharp gasp,” he said. “No one is rushing to

get anywhere.”

The place provided him needed space from his hospital roommates, of which he’s

had 10. He had overheard one on the phone orchestrating his funeral, what sort

of urn for his ashes.

Mr. Adebiyi was discharged this month. The search for a donor continues. Those

who knew him at the center hope that he will return soon and that the hospital

will have something to put in him, give his story a good ending. Meanwhile, he

went looking for a used skeleton sled. He needed to practice.

The Cancer Lounge, NYT,

29.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/29/nyregion/29cancer.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Fighting the Wrong Health Care Battle

November 29, 2009

The New York Times

By PAUL STARR

Princeton, N.J.

AS the health care debate enters its decisive stage, liberals in Congress should

be ready to trade the public option for provisions that will actually make the

reforms succeed.

Discussion of the public option — a government insurance plan that would be

offered to individuals and small businesses buying coverage through new

insurance exchanges — has been dominated by ideological politics. Conservatives

claim it would amount to a government takeover, while liberals imagine that it

would radically alter the insurance market by providing better protection at

lower cost.

As it now stands in Congress, however, the public option would do neither.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, it would enroll less than 2

percent of the population and probably have higher premiums than private plans.

For progressives to say they will block reform without a public option is not

just foolish, but potentially tragic if it results in legislative deadlock.

An earlier version of the public option, available to the entire public, might

have realized progressive hopes and conservative fears. By paying doctors and

hospitals at Medicare rates (which are 20 percent to 30 percent below those paid

by private insurers), the public option would have had a distinct price

advantage. But by severely cutting revenue to health-care providers, it would

also have set off such a political crisis that Congress would never have passed

it.

Instead, the bills in Congress now call for the government plan to negotiate

rates with providers, as private insurers do. That limitation exposes a defect

in the idea. The government plan may well have to charge higher premiums because

it is likely to attract more than its share of the chronically ill and other

high-cost subscribers. It could go into a death spiral of mounting costs.

But giving the exchanges the necessary authority to regulate private insurers

could solve many of the problems that motivated the public option in the first

place. Strengthening that authority and accelerating the timetable for reform

are what liberals in Congress should be looking for in a deal.

The basic aim of reform is to create a more efficient and equitable system for

health insurance and health care and to provide subsidies so everyone can afford

coverage. Those who obtain insurance individually or through small businesses

now get a rotten deal in the market. Out of every dollar in premiums they pay,

nearly 30 cents goes for administrative overhead (as opposed to about 7 cents in

large-employer plans). And those in poor health may be denied coverage for

pre-existing conditions or be charged astronomical rates for insurance.

By creating a single, large “risk pool” for individuals and employees of small

businesses, the exchanges should give those vulnerable groups the advantages of

large-employer plans. The bill would also ban pre-existing condition exclusions

and require insurers to offer coverage to everyone in the exchange at the same

rate regardless of health (albeit with some adjustment according to age).

For these reforms to succeed, there needs to be effective regulatory authority

to prevent insurers from engaging in abusive practices and subverting the new

rules. The bill passed by the House would provide for that authority and lodges

it in the federal government, though states could take over the exchanges if

they met federal requirements. The Senate bill would leave most of the

enforcement as well as the running of the exchanges to the states.

Yet many states have a poor record of regulating health insurance, and some

would resist passing legislation to conform with the new federal law. Under the

Senate bill, the federal government can step in if a state failed to set up an

exchange. But it’s hard enough to get reform through Congress; to try to repeat

that process in 50 state legislatures would be asking for trouble and

guaranteeing delay.

Accelerating the timetable of reform ought to be a priority. Although the

legislation calls for some important interim measures, the Senate bill defers

opening the exchanges and extending coverage until 2014. By comparison, when

Medicare was enacted in 1965, it went into effect the next year.

For Congress to put off expanding coverage to 2014 would be asking for a lot of

patience from voters. It would also give the opponents of reform two elections

to undo it. President Obama would have to run for re-election in 2012 defending

a program from which people would have seen little benefit.

To speed the process, the legislation ought to give states financial incentives

to adopt the reforms on their own as early as mid-2011. A state like

Massachusetts, which already has a working exchange, could move expeditiously to

qualify for federal money. The final deadline for the federal government’s

expansion of coverage should be no later than Jan. 1, 2012.

Let the moderate Democrats who oppose the public option say they stopped a

government takeover. Liberals should be prepared to give up what is now a mere

symbol for changes in the bill that would deliver affordable insurance more

effectively and quickly to the millions of Americans who desperately need it.

Paul Starr, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton, was a

senior health policy adviser in the Clinton administration.

Fighting the Wrong Health Care Battle, NYT,

29.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/29/opinion/29starr.html

Brain Power

Surgery for Mental Ills

Offers Hope and Risk

November 27, 2009

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

One was a middle-aged man who refused to get into the shower. The other was a

teenager who was afraid to get out.

The man, Leonard, a writer living outside Chicago, found himself completely

unable to wash himself or brush his teeth. The teenager, Ross, growing up in a

suburb of New York, had become so terrified of germs that he would regularly

shower for seven hours. Each received a diagnosis of severe obsessive-compulsive

disorder, or O.C.D., and for years neither felt comfortable enough to leave the

house.

But leave they eventually did, traveling in desperation to a hospital in Rhode

Island for an experimental brain operation in which four raisin-sized holes were

burned deep in their brains.

Today, two years after surgery, Ross is 21 and in college. “It saved my life,”

he said. “I really believe that.”

The same cannot be said for Leonard, 67, who had surgery in 1995. “There was no

change at all,” he said. “I still don’t leave the house.”

Both men asked that their last names not be used to protect their privacy.

The great promise of neuroscience at the end of the last century was that it

would revolutionize the treatment of psychiatric problems. But the first real

application of advanced brain science is not novel at all. It is a precise,

sophisticated version of an old and controversial approach: psychosurgery, in

which doctors operate directly on the brain.

In the last decade or so, more than 500 people have undergone brain surgery for

problems like depression, anxiety, Tourette’s syndrome, even obesity, most as a

part of medical studies. The results have been encouraging, and this year, for

the first time since frontal lobotomy fell into disrepute in the 1950s, the Food

and Drug Administration approved one of the surgical techniques for some cases

of O.C.D.

While no more than a few thousand people are impaired enough to meet the strict

criteria for the surgery right now, millions more suffering from an array of

severe conditions, from depression to obesity, could seek such operations as the

techniques become less experimental.

But with that hope comes risk. For all the progress that has been made, some

psychiatrists and medical ethicists say, doctors still do not know much about

the circuits they are tampering with, and the results are unpredictable: some

people improve, others feel little or nothing, and an unlucky few actually get

worse. In this country, at least one patient was left unable to feed or care for

herself after botched surgery.

Moreover, demand for the operations is so high that it could tempt less

experienced surgeons to offer them, without the oversight or support of research

institutions.

And if the operations are oversold as a kind of all-purpose cure for emotional

problems — which they are not, doctors say — then the great promise could

quickly feel like a betrayal.

“We have this idea — it’s almost a fetish — that progress is its own

justification, that if something is promising, then how can we not rush to

relieve suffering?” said Paul Root Wolpe, a medical ethicist at Emory

University.

It was not so long ago, he noted, that doctors considered the frontal lobotomy a

major advance — only to learn that the operation left thousands of patients with

irreversible brain damage. Many promising medical ideas have run aground, Dr.

Wolpe added, “and that’s why we have to move very cautiously.”

Dr. Darin D. Dougherty, director of the division of neurotherapeutics at

Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of psychiatry at

Harvard, put it more bluntly. Given the history of failed techniques, like

frontal lobotomy, he said, “If this effort somehow goes wrong, it’ll shut down

this approach for another hundred years.”

A Last Resort

Five percent to 15 percent of people given diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive

disorder are beyond the reach of any standard treatment. Ross said he was 12

when he noticed that he took longer to wash his hands than most people. Soon he

was changing into clean clothes several times a day. Eventually he would barely

come out of his room, and when he did, he was careful about what he touched.

“It got so bad, I didn’t want any contact with people,” he said. “I couldn’t hug

my own parents.”

Before turning to writing, Leonard was a healthy, successful businessman. Then

he was struck, out of nowhere, with a fear of insects and spiders. He overcame

the phobias, only to find himself with a strong aversion to bathing. He stopped

washing and could not brush his teeth or shave.

“I just looked horrible,” he said. “I had a big, ugly beard. My skin turned

black. I was afraid to be seen out in public. I looked like a street person. If

you were a policeman, you would have arrested me.”

Both tried antidepressants like Prozac, as well as a variety of other

medications. They spent many hours in standard psychotherapy for

obsessive-compulsive disorder, gradually becoming exposed to dreaded situations

— a moldy shower stall, for instance — and practicing cognitive and relaxation

techniques to defuse their anxiety.

To no avail.

“It worked for a while for me, but never lasted,” Ross said. “I mean, I just

thought my life was over.”

But there was one more option, their doctors told them, a last resort. At a

handful of medical centers here and abroad, including Harvard, the University of

Toronto and the Cleveland Clinic, doctors for years have performed a variety of

experimental procedures, most for O.C.D. or depression, each guided by

high-resolution imaging technology. The companies that make some of the devices

have supported the research, and paid some of the doctors to consult on

operations.

In one procedure, called a cingulotomy, doctors drill into the skull and thread

wires into an area called the anterior cingulate. There they pinpoint and

destroy pinches of tissue that lie along a circuit in each hemisphere that

connects deeper, emotional centers of the brain to areas of the frontal cortex,

where conscious planning is centered.

This circuit appears to be hyperactive in people with severe O.C.D., and imaging

studies suggest that the surgery quiets that activity. In another operation,

called a capsulotomy, surgeons go deeper, into an area called the internal

capsule, and burn out spots in a circuit also thought to be overactive.

An altogether different approach is called deep brain stimulation, or D.B.S., in

which surgeons sink wires into the brain but leave them in place. A

pacemaker-like device sends a current to the electrodes, apparently interfering

with circuits thought to be hyperactive in people with obsessive-compulsive

disorder (and also those with severe depression). The current can be turned up,

down or off, so deep brain stimulation is adjustable and, to some extent,

reversible.

In yet another technique, doctors place the patient in an M.R.I.-like machine

that sends beams of radiation into the skull. The beams pass through the brain

without causing damage, except at the point where they converge. There they burn

out spots of tissue from O.C.D.-related circuits, with similar effects as the

other operations. This option, called gamma knife surgery, was the one Leonard

and Ross settled on.

The institutions all have strict ethical screening to select candidates. The

disorder must be severe and disabling, and all standard treatments exhausted.

The informed-consent documents make clear that the operation is experimental and

not guaranteed to succeed.

Nor is desperation by itself sufficient to qualify, said Richard Marsland, who

oversees the screening process at Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I., which

works with surgeons at Rhode Island Hospital, where Leonard and Ross had the

operation.

“We get hundreds of requests a year and do only one or two,” Mr. Marsland said.

“And some of the people we turn down are in bad shape. Still, we stick to the

criteria.”

For those who have successfully recovered from surgery, this intensive screening

seems excessive. “I know why it’s done, but this is an operation that could make

the difference between life and death for so many people,” said Gerry Radano,

whose book “Contaminated: My Journey Out of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder”

(Bar-le-Duc Books, 2007), recounts her own suffering and long recovery from

surgery. She also has a Web site, freeofocd.com, where people from around the

world consult with her.

But for the doctors running the programs, this screening is crucial. “If

patients are poorly selected or not followed well, there’ll be an increasing

number of bad outcomes, and the promise of this field will wither away,” said

Dr. Ben Greenberg, the psychiatrist in charge of the program at Butler.

Dr. Greenberg said about 60 percent of patients who underwent either gamma knife

surgery or deep brain stimulation showed significant improvement, and the rest

showed little or no improvement. For this article, he agreed to put a reporter

in touch with one — Leonard — who did not have a good experience.

The Danger of Optimism

The true measure of an operation, medical ethicists say, is its overall effect

on a person’s life, not only on specific symptoms.

In the early days of psychosurgery, after World War II, doctors published scores

of papers detailing how lobotomy relieved symptoms of mental distress. In 1949,

the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz won the Nobel Prize in medicine for

inventing the procedure.

But careful follow-up painted a darker picture: of people who lost motivation,

who developed the helpless indifference dramatized by the post-op rebel McMurphy

in Ken Kesey’s novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” played by Jack Nicholson

in the 1975 movie.

The newer operations pinpoint targets on specific, precisely mapped circuits,

whereas the frontal lobotomy amounted to a crude slash into the brain behind the

eyes, blindly mangling whatever connections and circuits were in the way. Still,

there remain large gaps in doctors’ understanding of the circuits they are

operating on.

In a paper published last year, researchers at the Karolinska Institute in

Sweden reported that half the people who had the most commonly offered

operations for obsessive-compulsive disorder showed symptoms of apathy and poor

self-control for years afterward, despite scoring lower on a measure of O.C.D.

severity.

“An inherent problem in most research is that innovation is driven by groups

that believe in their method, thus introducing bias that is almost impossible to

avoid,” Dr. Christian Ruck, the lead author of the paper, wrote in an e-mail

message. The institute’s doctors, who burned out significantly more tissue than

other centers did, no longer perform the operations, partly, Dr. Ruck said, as a

result of his findings.

In the United States, at least one patient has suffered disabling brain damage

from an operation for O.C.D. The case led to a $7.5 million judgment in 2002

against the Ohio hospital that performed the procedure. (It is no longer offered

there.)

Most outcomes, whether favorable or not, have had less remarkable immediate

results. The brain can take months or even years to fully adjust after the

operations. The revelations about the people treated at Karolinska “underscore

the importance of face-to-face assessments of adverse symptoms,” Dr. Ruck and

his co-authors concluded.

The Long Way Back

Ross said he felt no difference for months after surgery, until the day his

brother asked him to play a video game in the basement, and down the stairs he

went.

“I just felt like doing it,” he said. “I would never have gone down there

before.”

He said the procedure seemed to give the psychotherapy sessions a chance to

work, and last summer he felt comfortable enough to stop them. He now spends his

days studying, going to class, playing the odd video game to relax. He has told

friends about the operation, he said, “and they’re O.K. with it — they know the

story.”

Leonard is still struggling, for reasons no one understands. He keeps odd hours,

working through most nights and sleeping much of the day. He is not unhappy, he

said, but he has the same aversion to washing and still lives like a hermit.

“I still don’t know why I’m like this, and I would still try anything that could

help,” he said. “But at this point, obviously, I’m skeptical of the efficacy of

surgery, at least for me.”

Ms. Radano, who wrote the book about her recovery, said the most important thing

about the surgery was that it gave people a chance. “That’s all people in this

situation want, and I know because I was there,” she said while getting into her

car on a recent afternoon.

On the passenger seat was a container of decontaminating hand wipes. She pointed

and laughed. “See? You’re never completely out.”

Surgery for Mental Ills

Offers Hope and Risk, NYT, 27.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/27/health/research/27brain.html

Trying to Explain a Drop

in Infant Mortality

November 27, 2009

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

MADISON, Wis. — Seven and a half months into Ta-Shai Pendleton’s first

pregnancy, her child was stillborn. Then in early 2008, she bore a daughter

prematurely.

Soon after, Ms. Pendleton moved from a community in Racine that was thick with

poverty to a better neighborhood in Madison. Here, for the first time, she had a

full-term pregnancy.

As she cradled her 2-month-old daughter recently, she described the fear and

isolation she had experienced during her first two pregnancies, and the more

embracing help she found 100 miles away with her third. In Madison, county

nurses made frequent home visits, and she got more help from her new church.

The lives and pregnancies of black mothers like Ms. Pendleton, 21, are now the

subject of intense study as researchers confront one of the country’s most

intractable health problems: the large racial gap in infant deaths, primarily

due to a higher incidence among blacks of very premature births.

Here in Dane County, Wis., which includes Madison, the implausible has happened:

the rate of infant deaths among blacks plummeted between the 1990s and the

current decade, from an average of 19 deaths per thousand births to, in recent

years, fewer than 5.

The steep decline, reaching parity with whites, is particularly intriguing,

experts say, because obstetrical services for low-income women in the county

have not changed that much.

Finding out what went right in Dane County has become an urgent quest — one that

might guide similar progress in other cities. In other parts of the state,

including Milwaukee, Racine and two other counties, black infant death rates

remain among the nation’s highest, surpassing 20 deaths per thousand in some

areas.

Nationwide for 2007, according to the latest federal data, infant mortality was

6 per 1,000 for whites and 13 for blacks.

“This kind of dramatic elimination of the black-white gap in a short period has

never been seen,” Dr. Philip M. Farrell, professor of pediatrics and former dean

of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, said of the

progress in Dane County.

“We don’t have a medical model to explain it,” Dr. Farrell added, explaining

that no significant changes had occurred in the extent of prenatal care or in

medical technology.

Without a simple medical explanation, health officials say, the decline appears

to support the theory that links infant mortality to the well-being of mothers

from the time they were in the womb themselves, including physical and mental

health; personal behaviors; exposure to stresses, like racism; and their social

ties.

Those factors could in turn affect how well young women take care of themselves

and their pregnancies.

Karen Timberlake, the Wisconsin secretary of health services, said that in Dane

County, the likely explanation lay in “the interaction among a variety of

interrelated factors.”

“Our challenge is,” Ms. Timberlake said, “how can we distill this and take it to

other counties?”

Only about 5 percent of Dane County’s population is black, and the sharp drop in

the mortality rate also tracked larger declines in the numbers of very premature

and underweight births for blacks, said Dr. Thomas L. Schlenker, the county

director of public health.

A three-year study, led by Dr. Gloria E. Sarto of the University of Wisconsin,

is using tools including focus groups and research on pollution to compare the

experiences of black mothers here with those in Racine County, which has the

highest black infant mortality in the state.

It is not hard to imagine why death rates would be lower in Dane County than in

Racine, which is more segregated and violent, or in Milwaukee, a larger city.

Dane County has a greater array of public and private services, but pinpointing

how they may have changed over the decade in ways that made a difference is the

challenge.

Dr. Schlenker, the county health director, credits heightened outreach to young

women by health workers and private groups. “I think it’s a community effect,”

he said. “Pregnant women need to feel safe, cared for and valued. I believe that

when they don’t, that contributes to premature birth and fetal loss in the sixth

or seventh month.”

He pointed to services that started in the mid-90s and have gathered steam. For

instance, a law center, ABC for Health, has increasingly connected poor women

with insurance and medical services. He said local health maintenance

organizations were now acting far more assertively to promote the health of

prospective mothers.

And a federally supported clinic, Access Community Health Center, which serves

the uninsured and others, has cared for a growing number of women using

nurse-midwives, who tend to bond with pregnant women, spending more time on

appointments and staying with them through childbirth.

County nurses visit low-income women at high risk of premature birth, providing

transportation to appointments and referrals to antismoking programs or

antidepression therapies. Another program sends social workers into some homes.

The programs exist statewide, but in Milwaukee, Racine and other areas they do

not appear to have achieved the same broad coverage, said Ms. Timberlake, the

state health leader.

And community leaders in Dane County, shocked by high mortality rates, started

keeping closer watch on young pregnant women.

“The African-American community in Madison is close-knit,” said Carola Gaines, a

black leader and coordinator of Medicaid services for a private insurance plan.

Similar community efforts are now being promoted in other struggling cities.

Brandice Hatcher, 26, who recently moved into a new, subsidized apartment in

Madison, spent her first 18 years in foster care in Chicago before moving two

years ago.

When she learned last June that she was pregnant, Ms. Hatcher said, “I didn’t

know how to be a parent and I didn’t know what services could help me.”

Over the summer she started receiving monthly visits from Laura Berger, a county

nurse, who put her in touch with a dentist. That was not just a matter of

comfort; periodontal disease elevates the risk of premature birth, increasing

the levels of a labor-inducing chemical.

Ms. Hatcher had been living in a rooming house, but she was able to get help

from a program that provided a security deposit for her apartment. She attained

certification as a nursing assistant while awaiting childbirth.

Under a state program, a social worker visits weekly and helps her look for

jobs. And she receives her prenatal care from the community center’s

nurse-midwives. A church gave her baby clothes and a changing table.

Ms. Hatcher said she would not do anything to jeopardize her unborn baby’s

prospects. She has named her Zaria and is collecting coins and bills in a glass

jar, the start, she said, of Zaria’s personal savings account.

Trying to Explain a Drop

in Infant Mortality, NYT, 27.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/27/us/27infant.html

From the Hospital Room

to Bankruptcy Court

November 25, 2009

The New York Times

By KEVIN SACK

NASHVILLE — Some of the debtors sitting forlornly in this city’s old stone

bankruptcy court have lost a job or gotten divorced. Others have been summoned

to face their creditors because they spent mindlessly beyond their means. But

all too often these days, they are there merely because they, or their children,

got sick.

Wes and Katie Covington, from Smyrna, Tenn., were already in debt from a round

of fertility treatments when complications with her pregnancy and surgery on his

knee left them with unmanageable bills. For Christine L. Phillips of Nashville,

it was a $10,000 trip to the emergency room after a car wreck, on the heels of

costly operations to remove a cyst and repair a damaged nerve.

Jodie and Charlie Mullins of Dickson, Tenn., were making ends meet on his

patrolman’s salary until she developed debilitating back pain that required

spinal surgery and forced her to quit nursing school. As with many medical

bankruptcies, they had health insurance but their policy had a $3,000 deductible

and, to their surprise, covered only 80 percent of their costs.

“I always promised myself that if I ever got in trouble, I’d work two jobs to

get out of it,” said Mr. Mullins, a 16-year veteran of the Dickson police force.

“But it gets to the point where two or three or four jobs wouldn’t take care of

it. The bills just were out of sight.”

Although statistics are elusive, there is a general sense among bankruptcy

lawyers and court officials, in Nashville as elsewhere, that the share of

personal bankruptcies caused by illness is growing.

In the campaign to broaden support for the overhaul of American health care, few

arguments have packed as much rhetorical punch as the

there-but-for-the-grace-of-God notion that average families, through no fault of

their own, are going bankrupt because of medical debt.

President Obama, in addressing a joint session of Congress in September, called

on lawmakers to protect those “who live every day just one accident or illness

away from bankruptcy.” He added: “These are not primarily people on welfare.

These are middle-class Americans.”

The Senate majority leader, Harry Reid of Nevada, made a similar case on

Saturday in a floor speech calling for passage of a measure to open debate on

his chamber’s health care bill.

The legislation moving through Congress would attack the problem in numerous

ways.

Bills in both houses would expand eligibility for Medicaid and provide health

insurance subsidies for those making up to four times the federal poverty level.

Insurers would be prohibited from denying coverage to those with pre-existing

health conditions. Out-of-pocket medical costs would be capped annually.

How many personal bankruptcies might be avoided is unpredictable, as it is not

clear how often medical debt plays a back-breaking role. There were 1.1 million

personal bankruptcy filings in 2008, including 12,500 in Nashville, and more are

expected this year.

Last summer, Harvard researchers published a headline-grabbing paper that

concluded that illness or medical bills contributed to 62 percent of

bankruptcies in 2007, up from about half in 2001. More than three-fourths of

those with medical debt had health insurance.

But the researchers’ methodology has been criticized as defining medical

bankruptcy too broadly and for the ideological leanings of its authors, some of

whom are outspoken advocates for nationalized health care.

At the bankruptcy court in Nashville, lawyers provided a spectrum of estimates

for the share of cases in Middle Tennessee where medical debt was decisive, from

15 percent to 50 percent. But many said they felt the number had been growing,

and might be higher than was obvious because medical bills are often disguised

as credit card debt.

“This has really become the insurance system for the country,” said Susan R.

Limor, a bankruptcy trustee who calculated that 13 of the 48 Chapter 7

liquidation cases on her docket one recent afternoon included medical debts of

more than $1,000.

Under Chapter 7, a debtor’s assets are liquidated and the proceeds are used to

pay creditors; any remaining debts are discharged, and filers are left with a

10-year stain on their credit ratings.

“You can’t believe how many people discharge medical debts,” Ms. Limor said.

“It’s a kind of trailing indicator of who’s suffering in this economy.”

Kyle D. Craddock, a bankruptcy lawyer here, said his medical cases were

heartbreaking because the financial devastation was so rapid and ill-timed.

“They’re sick, they’re bankrupt, and if they stay sick for too long, they end up

losing their jobs as well,” he said.

That was the case for Ms. Phillips, 45, who said she was fired in October from

her job in a shipping department because she had missed so much work while

recuperating from her car accident and operations. Her firing came only 11 days

after she filed for bankruptcy, listing about $7,000 in unpaid medical bills

among her $187,000 in liabilities.

“The medical bills put me over the edge,” said Ms. Phillips, who lost her health

insurance along with her job. “I had no money for food at this point. How was I

going to do it?”

It was the same for the Mullinses, who have two children. They had a mortgage

and owed money on credit cards and student loans. “But the medical problem is

what took us down,” said Ms. Mullins, who is packing to move from the

two-bedroom house they will soon surrender to Wells Fargo. “Everything was due,

they wanted their money now, now, now, and it just became overwhelming.”

For some, like Nathan W. Hale, 34, who had an attack of pancreatitis two months

after losing his job with a Nashville cable company, it is the absence of

insurance that pulls them under. Others, like Robin P. Herron, 35, of

Eagleville, Tenn., have insurance, but it is not enough. Her Blue Cross Blue

Shield policy covered only 80 percent of the cost when her daughter needed

surgery to remove a cyst from a fallopian tube, leaving her $6,000 in debt.

After cortisone injections failed to cure his gimpy knee, Mr. Covington, 31, had

surgery because the pain was forcing him to miss days of work as an emergency

medical technician. His recovery kept him off the job for five months.

Simultaneously, his wife, a 911 dispatcher, developed sciatica while pregnant

and had to take months off on reduced disability pay. Their insurance policy,

with an $850 monthly premium, has a $4,000 annual deductible per family.

As the bills rolled in, the Covingtons compounded their troubles by placing

medical charges on credit cards, simply to make the collection agencies stop

calling. They fell months behind on their mortgage, and by August had lost their

house and both cars.

Mr. Covington, who has taken a second job, said he found it ironic that it had

not been the recession that forced them into bankruptcy. “I tell my wife that we

beat the economy,” he said, “but health care beat us.”

From the Hospital Room

to Bankruptcy Court, NYT, 25.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/25/health/policy/25bankruptcy.html

Scared and Silent, Runaway, 13,

Spent 11 Days in the Subways

November 24, 2009

The New York Times

By KIRK SEMPLE

Day after day, night after night, Francisco Hernandez Jr. rode the subway. He

had a MetroCard, $10 in his pocket and a book bag on his lap. As the human tide

flowed and ebbed around him, he sat impassively, a gangly 13-year-old boy in

glasses and a red hoodie, speaking to no one.

After getting in trouble in class in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, and fearing another

scolding at home, he had sought refuge in the subway system. He removed the

battery from his cellphone. “I didn’t want anyone to scream at me,” he said.

All told, Francisco disappeared for 11 days last month — a stretch he spent

entirely in subway stations and on trains, he says, hurtling through four

boroughs. And somehow he went undetected, despite a round-the-clock search by

his panicked parents, relatives and family friends, the police and the Mexican

Consulate.

Since Oct. 26, when a transit police officer found him in a Coney Island subway

station, no one has been able to fully explain how a boy could vanish for so

long in a busy train system dotted with surveillance cameras and fliers bearing

his photograph.

But this was not a typical missing-person search. Francisco has Asperger’s

syndrome, a form of autism that often causes difficulty with social interaction,

and can lead to seemingly eccentric behavior and isolation. His parents are

Mexican immigrants, who say they felt the police were slow to make the case a

priority.

“Maybe because you might not understand how to manage the situation, because you

don’t speak English very well, because of your legal status, they don’t pay you

a lot of attention,” said Francisco’s mother, Marisela García, 38, a

housecleaner who immigrated in 1994 and has struggled to find ways to help her

son.

The police, however, say they took the case seriously from the start,

interviewing school officials and classmates, canvassing neighborhoods and

leafleting all over the city.

Francisco says his odyssey wound through three subway lines: the D, F and No. 1.

He would ride a train until its last stop, then wait for the next one, wherever

it was headed. He says he subsisted on the little he could afford at subway

newsstands: potato chips, croissants, jelly rolls, neatly folding the wrappers

and saving them in the backpack. He drank bottled water. He used the bathroom in

the Stillwell Avenue station in Coney Island.

Otherwise, he says, he slipped into a kind of stupor, sleeping much of the time,

his head on his book bag. “At some point I just stopped feeling anything,” he

recalled.

Though the boy’s recollections are incomplete, and neither the police nor his

family can retrace his movements in detail, the authorities say that he was

clearly missing for 11 days and that they have no evidence he was anywhere but

the subway.

For his parents, the memories of those 11 frantic days — the dubious sightings,

the dashed hopes and no sleep — remain vivid. “It’s the most terrible thing,”

his mother said in Spanish.

Just what propelled Francisco to take flight on Oct. 15 is unclear.

Administrators at his school, Intermediate School 281, would not comment. But

Francisco said he had failed to complete an assignment for an eighth-grade

class, and was scolded for not concentrating.

After school, he phoned his mother to say he was heading home. She told him the

school had called and she wanted a serious talk with him.

His first impulse was to flee. He walked eight blocks to the Bay Parkway station

and boarded a D train. It seemed a safe place to hide, he said.

When he did not arrive home, his mother started to panic. In January, after

another problem at school, Francisco had left home and ridden the subway, but

returned after five hours. “We thought this time it would be the same,” Ms.

García said. “But unfortunately it wasn’t.”

Her husband, also named Francisco Hernandez, went to the nearest subway station

and waited for several hours while she stayed at home on Bay 25th Street with

their 9-year-old daughter, Jessica. After midnight, the couple called the

police, and two officers from the 62nd Precinct visited their apartment.

The next morning, Mr. Hernandez, 32, a construction laborer, borrowed a bicycle

and scoured Bensonhurst. He and his wife separately explored the subway from

Coney Island to Midtown Manhattan.

They had been trying to help their son for years. Born in Brooklyn, Francisco

grew up a normal child in many ways, his mother said, earning mostly passing

grades and enjoying drawing and video games. But he had no friends outside

school, and found it difficult to express emotions. A gentle, polite boy, he

spoke — when he did speak — in a soft monotone.

In 2006, his parents had him evaluated at a developmental disabilities research

clinic on Staten Island, where his Asperger’s was diagnosed. The clinic’s chief

neuropsychologist concluded that Francisco struggled in situations that demanded

a “verbal or social response.”

“His anxiety level can elevate, and he freezes in confusion because he does not

know what to do or say,” the doctor wrote.

After he disappeared, his parents printed more than 2,000 color leaflets with a

photo of Francisco wearing the same red hoodie; friends and relatives helped

post them in shops, on the street and throughout the subway in Brooklyn. The

family hand-lettered fluorescent-colored signs.

“Franky come home,” one pleaded in Spanish. “I’m your mother I beg you I love

you my little boy.”

Francisco said he never saw the signs. He lost sense of time. He was prepared,

he said, to remain in the subway system forever.

No one spoke to him. Asked if he saw any larger meaning in that, he said,

“Nobody really cares about the world and about people.”

Sightings were reported. An image of a boy resembling Francisco had been

captured by a video game store’s security camera, but he turned out to be

someone else, the police said. A stranger called Mr. Hernandez to say he had

spotted Francisco with some boys at a movie theater in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn.

A search turned up nothing.

Ms. García said one detective told her the boy was probably hiding out with a

friend. She replied that her son had no friends to hide out with. Frustrated,

the parents sought help from the Mexican Consulate. Officials there contacted

the Spanish-language news media, which ran brief newspaper and television

reports about Francisco, and called the police — “to use the weight that we have

to encourage them, to tell them that we have an emergency,” a consular spokesman

said.

Six days after Francisco’s disappearance, on Oct. 21, the case shifted from the

police precinct to the Missing Persons Squad, and the search intensified. A

police spokeswoman explained that a precinct must complete its preliminary

investigation before the squad takes over.

The squad’s lead investigator on the case, Detective Michael Bonanno, said he

turned the focus to the subway. He and his colleagues blanketed the system with

their own signs, rode trains and briefed station attendants.

About 6 a.m. on Oct. 26, the police said, a transit officer stood on the D train

platform at the Stillwell Avenue station studying a sign with Francisco’s photo.

He turned and spotted a dirty, emaciated boy sitting in a stopped train. “He

asked me if I was Francisco,” the boy recalled. “I said yes.”

Asked later how it felt to hear about the work that had gone into finding him,

Francisco said he was not sure. “Sometimes I don’t know how I feel,” he said. “I

don’t know how I express myself sometimes.”

Apart from leg cramps, he was all right physically, and returned to school a

week later. But Ms. García said she was still trying to learn how to manage her

son’s condition. Though doctors had recommended that Francisco be placed in a

small school for children with learning disorders, she said, officials at his

school told her he was testing fine and did not need to be transferred.

“I tell him: ‘Talk to me. Tell me what you need. If I ever make a mistake, tell

me,’ ” she said. “I don’t know, as a mother, how to get to his heart, to find

out what hurts.”

One of the fluorescent signs hangs on the living room wall. The others are

stacked discreetly in a corner, and Ms. García said she was not ready to discard

them.

“It’s not easy to say it’s over and it won’t happen again,” she said.

Scared and Silent,

Runaway, 13, Spent 11 Days in the Subways, NYT, 24.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/nyregion/24runaway.html

Shifting Vaccine for Flu to Elderly

November 24, 2009

The New York Times

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr.

Federal health officials are trying to shift supplies of the seasonal flu

vaccine away from chain pharmacies and supermarkets to nursing homes, hoping to

counter a shortage that threatens to cause a wave of deaths this winter among

the nation’s most vulnerable population.

The extent of the shortage is still unclear, but Janice Zalen, director of

special programs for the American Health Care Association, which represents

11,000 nursing homes and assisted-living facilities, called it “a very big

problem.”

Ms. Zalen said that of 1,000 nursing home managers who responded to a survey of

the association’s 11,000 members, 800 reported they could not get enough

vaccine.

Dr. Carol Friedman, head of adult immunization at the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, said she did not have a figure for the size of the

shortage, but added, “It’s a problem, and it’s all over the country.”

Mary Hahn, who manages six Ohio nursing homes with 800 beds, said she could not

get vaccine for any of her patients.

“It’s just so disheartening, because we’re having to leave people unprotected,”

she said. “You see people get flus and get sent to the hospital because they

really can’t fight it off.”

A nationwide shortage of the seasonal flu vaccine has been reported for several

weeks, but nursing homes and their suppliers have grown more alarmed in recent

days. Of the 36,000 Americans who die of seasonal flu in the average year, more

than 90 percent are 65 or older, and nursing home outbreaks are particularly

deadly. By contrast, the swine flu epidemic has been most deadly among younger

people.

The nursing homes’ predicament has been caused by a confluence of factors.

Because of the swine flu pandemic, far more people than usual are seeking

vaccination, Dr. Friedman said — even though the seasonal vaccine does not

protect against swine flu.

The five companies licensed to make flu shots for the United States originally

planned to make only slightly more than the 118 million they made in 2008. Then,

production problems caused GlaxoSmithKline to cut its run by half; Novartis’s

shrank by 10 percent. Then all five companies had to switch over early to making

swine flu vaccine.

So the total supply of vaccine is about 114 million doses, of which about 95

million have been shipped.

At the same time, reports of price gouging have grown more frequent. That also

happened in 2004, when sterility problems at a British plant cut the American

flu vaccine supply in half; prices shot up as high as $90 a dose, from the

normal level of $8 to $9.

Gouging is illegal in about half the states, but each state varies in how big a

price increase constitutes gouging and as to whether an emergency must have been

declared for the law to kick in.

“To pursue a case, we need to show it’s not just a couple of dollars but is very

significant,” said Attorney General Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, who has

opened an investigation.

Criminal charges are less likely than a civil suit, Mr. Blumenthal said. But he

added that if distributors were “masquerading or fraudulently claiming to have

vaccine,” that could end in a criminal charge. While he had suspicions, he said,

“we don’t have hard evidence yet.”

Dr. Friedman said that once the agency became aware of the shortage at nursing

homes, “we began working with the manufacturers to see if they could redirect

some of their vaccine.”

“Several big-box retailers and pharmacies volunteered to go into the

long-term-care facilities and set up flu clinics,” she said.

Dr. Friedman said she knew of one major supplier to nursing homes that received

100,000 fewer doses from the vaccine makers than it had ordered. Her agency

began acting as a broker among the homes, vaccine distributors and other

customers. Since then, she said, that supplier has found about 50,000 more

doses.

“That’s definitely not going to close the gap,” she said, “but it will help.”

Also, both she and Ms. Zalen said, pharmacy and supermarket chains like

Walgreen’s and Safeway that bought millions of doses to sell for $25 to $30 have

offered to give shots in nursing homes. They do not charge but get Medicare

reimbursements, which vary by state but run up to $25.

By contrast, Bob McKay, chief of sales for PharMerica, one of the two largest

wholesale pharmacies supplying nursing homes, said he had received 95 percent of

the 300,000 doses he ordered and “the voids are getting filled in” at the

nursing homes he supplies.

“We’re not hearing rage and craziness out there,” Mr. McKay said. “If a lot of

homes were still short, they’d be beating our doors down.”

But he said he had asked some not to buy shots for their staffs. Flu experts say

that in nursing homes, vaccination of staff members is just as important as

patient vaccination.

Prices offered to PharMerica for the extra doses they needed were “in the

$15-$16 range,” Mr. McKay said. “That’s more than we’d normally pay, but not

price-gouging.”

Jim Mathews, an executive at Hometown Pharmacy, a smaller wholesale

pharmaceutical company supplying Michigan nursing homes, said that late last

month he found himself 3,000 doses short; his usual supplier, which charges

$6.75 per dose, was out of stock. He called the C.D.C. for advice, was directed

to a Web page listing other suppliers and contacted all 10. Only one had

vaccine, and it sent him a fax in broken English asking for $57 to $59 per dose.

Mr. Mathews said he reported that to local law enforcement officials, but he is

more worried about the patients who will not get shots.

“When I first recognized the potential death toll from this shortage, there was

time to prioritize the remaining supply for the most vulnerable elderly,” he

said. “Now I’m afraid it’s too late. From what I see, the seasonal flu vaccine

shortage is going to cost more lives than the H1N1 shortage is.”

Dr. Friedman, of the C.D.C., said she had heard of “about 15” price-gouging

complaints.

Dr. Lillian Overman, an internist in East Hartford, Conn., was one of the first

to alert Mr. Blumenthal, the state’s attorney general, about gouging

accusations. On Oct. 26, her office manager began looking for vaccine, for which

she normally pays $8.50 a dose. A saleswoman at ABO Pharmaceuticals in San Diego

wanted $60 per dose, she said.

“That’s just prohibitive,” a frustrated Dr. Overman said. “If I’d known there

would be a shortage, I would have called in my most vulnerable patients first.”

Mark Nemeth, an ABO sales manager, denied that anyone there had asked for $60.

“I can guarantee you without a shadow of a doubt, we would never have offered it

at that price,” he said; the company is asking “in the ballpark of $12 to $14”

for its remaining supplies.

Shifting Vaccine for Flu

to Elderly, NYT, 24.11.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/health/24flu.html

Health Care Debate

Revives Abortion Campaigners

November 24, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID D. KIRKPATRICK

WASHINGTON — Lobbying over abortion was turning into a sleepy business. But

the health care debate has brought a new boom, and both sides are exploiting it

with fund-raising appeals.

“The reaction has been phenomenal, like a match dropped on dry kindling,” said

Cecile Richards, president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Abortion opponents have been blanketing their supporters with solicitations and

alarms since House Democrats laid out their health care proposals three months

ago. “The largest expansion of abortion since Roe vs. Wade,” warns the Web site

Stop the Abortion Mandate, which directs visitors to sign up with the

anti-abortion fund-raising group Susan B. Anthony List.

“It is far and away, in the history of our group, the biggest fulcrum of

activism we have ever had,” said Marjorie Dannenfelser, the group’s president,

adding that the 12-year-old organization has seen its contributions spike more

than 50 percent from 2007, the last year without a national election. Among

other things, her group is using the money for automated phone campaigns in

pivotal states and spending more than $130,000 on an advertising campaign aimed

at Senator Harry Reid, the Democratic leader, in his home state of Nevada. (The

National Right to Life Committee is soliciting donations at

stoptheabortionagenda.com.)

Abortion-rights groups got into the act two weeks ago, when the House of

Representatives adopted an amendment sponsored by Representative Bart Stupak,

Democrat of Michigan, to block the use of federal subsidies for policies that

cover abortion. “Stop Abortion Coverage Ban!,” declares an online solicitation

from NARAL Pro-Choice America, warning that “Women could lose the right to use

their own personal, private funds to purchase an insurance plan with abortion

coverage in the new health system.”

“Stop Stupak!,” is the headline of a new online petition that doubles as a

fund-raiser for Emily’s List, which raises money for female candidates who

support abortion rights. The group’s president, Ellen Malcolm, said in an

interview that she had not seen such an outpouring of support since Webster vs.

Reproductive Health Services, the 1989 Supreme Court decision that appeared to

re-open the question of a right to the procedure.

“Women are up in arms,” Ms. Malcolm said, adding that her group had made an

exception to its no-lobbying policy to pressure the women it helped elect.

This week the Web site of Cosmopolitan Magazine carried a “Secrets and Advice”

column entitled “Are Your Rights in Jeopardy?” that directed readers to a

similar “Stop Stupak” Web site from the Planned Parenthood Federation of

America. A third “Stop Stupak” campaign, by a group called the Progressive

Change Campaign Committee, has raised more than $23,000 from more than 700

donors since it started Nov. 11, according to its host, the online fund-raising

venture ActBlue.

“We have seen money coming in at every level,” said Ms. Richards of Planned

Parenthood, which is also patching calls into lawmakers’ offices in several

states. “Congressman Stupak managed to crystallize this movement in a way that

is hard to replicate.”

Veteran observers of the fight say that each side feels an honest threat from

the legislation. “It is not like burning your house down to collect the

insurance,” said Rachel Laser, of the moderate Democratic group Third Way.

But the practical stakes for abortion are in some ways quite narrow. No one in

the debate proposes adding or removing restrictions on the procedure itself. And

leaders of both parties say their goal is to avoid using federal tax money to

pay for abortion while subsidizing insurance coverage.

Democratic leaders favor requiring insurance companies to segregate any federal