|

History > 2009 > USA > Health (VI)

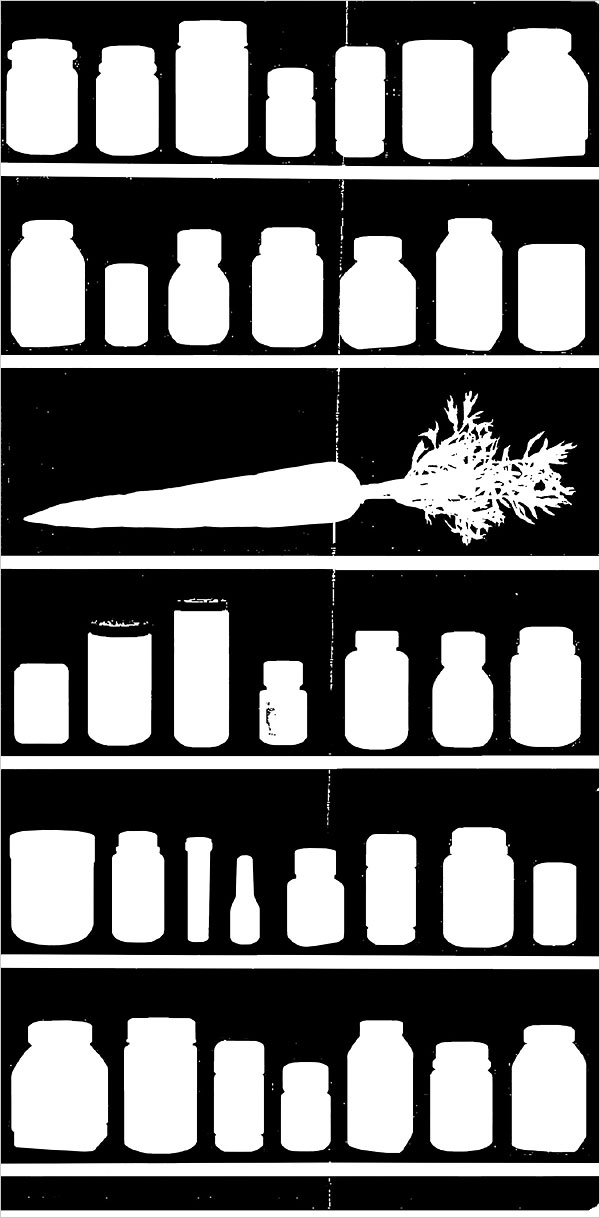

Illustration: Brian Rea

Putting America on a

Healthier Diet

NYT

12.9.2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/12/

opinion/l12pollan.html

Swine Flu Spreading Widely;

Worry Over Pregnant Women

October 2, 2009

The New York Times

By DONALD G. MCNEIL Jr.

Swine flu is now widespread across the entire country, the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention announced Thursday as federal health officials

released Tamiflu for children from the national stockpile and began taking

orders from the states for the new swine flu vaccine.

Also, as anecdotal reports and at least one poll showed that many Americans are

nervous about the vaccine, officials emphasized that the new shots were nearly

identical to seasonal ones, and said they were doing what they could to debunk

myths about the vaccine.

Dr. Anne Schuchat, the disease control center’s director of immunization and

respiratory disease, said there was “significant flu activity in virtually all

states,” which, she added, was “quite unusual for this time of year.”

Dr. Schuchat expressed particular worry about pregnant women. As of late August,

100 had been hospitalized in intensive care, and 28 had died since the beginning

of the outbreak in April.

“These are really upsetting numbers,” she said, urging obstetricians and

midwives to advise patients to get swine flu shots as soon as they become

available.

Also on Thursday, a 23-year-old recruit in basic training in Fort Jackson, S.C.,

was acknowledged Thursday to be the Army’s first swine flu death. The recruit,

Specialist Christopher M. Hogg of Deltona, Fla., fell ill on Sept. 1 and died of

pneumonia on Sept. 10, the military said. Although Specialist Hogg initially

tested negative for swine flu, it was found on autopsy.

About 50,000 troops a year train at Fort Jackson. (The camp was hit hard by the

Spanish influenza in 1918, when up to 5 percent of the recruits died, according

to a military historian quoted by The Associated Press.)

Flu cases are rising in many parts of the country, according to local news media

reports.

Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Tex., erected two tents in its parking

lot to handle emergency room visits, and hospitals near Colorado Springs had a

30 percent spike in flu visits. Several North Carolina hospitals barred children

from visiting.

Because pediatric cases are increasing, the Department of Health and Human

Services on Tuesday released 300,000 courses of children’s liquid Tamiflu from

the national pandemic stockpile, with the first batches going to Texas and

Colorado.

Some was past its expiration date, Dr. Schuchat said, but the Food and Drug

Administration tested the stocks and certified them as still usable.

More than 99 percent of all swine flu cases are mild to moderate, but millions

of people with relatively common problems like asthma, obesity, diabetes or

heart problems are at higher risk, as are pregnant women and infants too young

for vaccine.

The last disease centers count of child deaths from the flu was 36 as of Aug. 8.

Since then, there have been reports of children dying in several states, mostly

in the South, where schools reopened earlier.

Last week, the centers reported that 936 Americans had died of flu symptoms or

of flu-associated pneumonia since Aug. 30, when it began a new count of deaths

including some without lab-confirmed swine flu. That is few compared with the

36,000 that die annually of seasonal flu, but the deaths are concentrated in age

groups that do not normally succumb, and the regular flu season will not arrive

until November.

Confirming the centers’ anxiety that many Americans are reluctant to get swine

flu shots, Consumer Reports released a poll late Wednesday showing that half of

all parents surveyed said they were worried about the flu, but only 35 percent

would definitely have their children vaccinated. About half were undecided, and

of those, many said they feared that the vaccine was new and untested.

One worrying aspect, said Dr. John Santa, the director of health ratings at

Consumer Reports, was that 69 percent of parents who were undecided or opposed

to shots said they “wanted their children to build up their natural immunity.”

“Your body produces exactly the same antibodies, whether it’s from a ‘natural’

infection or from a vaccine,” Dr. Santa said. “If your child is the one that

dies, you’ve paid a very high price for ‘natural’ immunity.”

(The poll was a telephone survey of 1,502 adults from Sept. 2 to Sept. 7, with a

margin of sampling error of plus or minus three percentage points.)

Dr. Schuchat argued that the vaccine was neither new nor untested.

It is attached to the same “genetic backbone” of weakened flu virus as the 100

million seasonal flu injections given each year, grown in the same sterile eggs

and purified in the same factories. And test injections done in September found

that it had the same side effects, most of which were sore arms and mild fevers.

Scientists at the disease centers also looked at lung samples from 77 fatal

swine flu cases and found that in about a third of the cases, the patient had

died not from flu alone, but from bacteria that infiltrate when flu inflames the

lungs.

The “good news,” Dr. Schuchat said, is that most infections were streptococcus

pneumoniae, a common bacteria for which there is a vaccine. That vaccine is

normally given only to people over 65 or with chronic heart and lung problems,

but only about one in five Americans eligible for that shot ever gets it. More

people in those categories should, she said.

Swine Flu Spreading

Widely; Worry Over Pregnant Women, NYT, 2.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/02/health/02flu.html

After a Death,

the Pain That Doesn’t Go Away

September 29, 2009

TH e New York Times

By FRAN SCHUMER

Each of the 2.5 million annual deaths in the United States directly affects

four other people, on average. For most of these people, the suffering is finite

— painful and lasting, of course, but not so disabling that 2 or 20 years later

the person can barely get out of bed in the morning.

For some people, however — an estimated 15 percent of the bereaved population,

or more than a million people a year — grieving becomes what Dr. M. Katherine

Shear, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia, calls “a loop of suffering.” And

these people, Dr. Shear added, can barely function. “It takes a person away from

humanity,” she said of their suffering, “and has no redemptive value.”

This extreme form of grieving, called complicated grief or prolonged grief

disorder, has attracted so much attention in recent years that it is one of only

a handful of disorders under consideration for being added to the DSM-V, the

American Psychiatric Association’s handbook for diagnosing mental disorders, due

out in 2012.

Some experts argue that complicated grief should not be considered a separate

condition, merely an aspect of existing disorders, like depression or

post-traumatic stress. But others say the evidence is convincing.

“Of all the disorders I’ve heard proposed, they have better data for this than

almost any of the other possible topics,” said Dr. Michael B. First, a professor

of clinical psychiatry at Columbia and an editor of the current manual, DSM-IV.

“It would be crazy of them not to take it seriously.”

There is no formal definition of complicated grief, but researchers describe it

as an acute form persisting more than six months, at least six months after a

death. Its chief symptom is a yearning for the loved one so intense that it

strips a person of other desires. Life has no meaning; joy is out of bounds.

Other symptoms include intrusive thoughts about death; uncontrollable bouts of

sadness, guilt and other negative emotions; and a preoccupation with, or

avoidance of, anything associated with the loss. Complicated grief has been

linked to higher incidences of drinking, cancer and suicide attempts.

“Simply put,” Dr. Shear said, “complicated grief can wreck a person’s life.”

In 2004, Stephanie Muldberg of Short Hills, N.J., lost her son Eric, 13, to

Ewing’s sarcoma, a bone cancer. Four years after Eric’s death, Ms. Muldberg, now

48, walked around like a zombie. “I felt guilty all the time, guilty about

living,” she said. “I couldn’t walk into the deli because Eric couldn’t go there

any longer. I couldn’t play golf because Eric couldn’t play golf. My life was a

mess.

“And I couldn’t talk to my friends about it, because after a while they didn’t

want to hear about it. ‘Stephanie, you need to get your life back,’ they’d say.

But how could I? On birthdays, I’d shut the door and take the phone off the

hook. Eric couldn’t have any more birthdays; why should I?”

Hours of therapy and support groups later, Ms. Muldberg was referred to a

clinical trial at Columbia. After 16 weeks of a treatment developed by Dr.

Shear, she was able to resume a more normal life. She learned to play bridge,

went on a family vacation and read a book about something other than dying.

A crucial phase of the treatment, borrowed from the cognitive behavioral therapy

used to treat victims of post-traumatic stress disorder, requires the patient to

recall the death in detail while the therapist records the session. The patient

must replay the tape at home, daily. The goal is to show that grief, like the

tape, can be picked up or put away.

“I’d never been able to do that before, to put it away,” Ms. Muldberg said. “I

was afraid I’d lose the memories, lose Eric.”

For some, the recounting is the hardest part of recovering. “That was just

brutal and I had to relive it,” said Virginia Eskridge, 66, who began treatment

20 years after the death of her husband, Fred Adelman, a college professor in

Pittsburgh. “I nearly dropped out, but I knew this was my last hope of getting

any kind of functional life back.”

At the same time patients learn to handle their grief, they are encouraged to

set new goals. For Ms. Eskridge, a retired law school librarian, that meant

returning to the campus where her husband had taught.

“Everywhere I went there were reminders of him, because we had been everywhere,”

she said. “It was like I was getting stabbed in the heart every time I went

somewhere.”

That feeling finally went away, and Ms. Eskridge was even able to visit her

husband’s old office. “It really gave me my life back,” she said of the

treatment. “It sounds extreme, but it’s true.”

In a 2005 study in The Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. Shear

presented evidence that the treatment was twice as effective as the traditional

interpersonal therapy used to treat depression or bereavement, and that it

worked faster. The study supported earlier suggestions that complicated grief

might actually be different not only from normal grief but also from other

disorders like post-traumatic stress and major depression.

Then, in 2008, NeuroImage published a study of the brain activity of people with

complicated grief. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Mary-Frances

O’Connor, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California,

Los Angeles, showed that when patients with complicated grief looked at pictures

of their loved ones, the nucleus accumbens — the part of the brain associated

with rewards or longing — lighted up. It showed significantly less activity in

people who experienced more normal patterns of grieving.

“It’s as if the brain were saying, ‘Yes I’m anticipating seeing this person’ and

yet ‘I am not getting to see this person,’ ” Dr. O’Connor said. “The mismatch is

very painful.”

The nucleus accumbens is associated with other kinds of longing — for alcohol

and drugs — and is more dense in the neurotransmitter dopamine than in

serotonin. That raises two interesting questions: Could memories of a loved one

have addictive qualities in some people? And might there be a more effective

treatment for this kind of suffering than the usual antidepressants, whose

target is serotonin?

Experts who question whether complicated grief is a distinct disorder argue that

more research is needed. “You can safely say that complicated grief is a

disorder, a collection of symptoms that causes distress, which is the beginning

of the definition of a disease,” said Dr. Paula J. Clayton, medical director of

the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “However, other validators are

needed: family history and studies that follow the course of a disorder. For

example, once it’s cured, does it go away or show up years later as something

else, like depression?”

George A. Bonanno, a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia known for his

work on resilience (the reaction of the 85 percent of the population that does

adapt to loss), was skeptical at first. But, Dr. Bonanno said, “I ran those

tests and, lo and behold, extra grief symptoms were very important in predicting

what was going on with these people, over and above depression and P.T.S.D.”

Regardless of how complicated grief is classified, the discussion highlights a

larger issue: the need for a more nuanced look at bereavement. The DSM-IV

devotes only one paragraph to the topic.

Studies suggest that therapy for bereavement in general is not very effective.

But Dr. Bonanno called the published data “embarrassingly bad” and noted they

tended to lump in results from “a lot of people who don’t need treatment” but

sought it at the insistence of “loved ones or misguided professionals.”

Even if clinicians did identify people with complicated grief, there would not

be enough therapists to treat them. Despite Dr. Shear’s “terrific research” on

the therapy she pioneered, said Dr. Sidney Zisook, a professor of psychiatry at

the University of California, San Diego, “there aren’t a lot of people out there

who are trained to do it, and there aren’t a lot of patients with complicated

grief who are benefiting from this treatment breakthrough.”

The issue is pressing given the links between complicated grief and a higher

incidence of suicide, social problems and serious illness. “Do the symptoms of

prolonged grief predict suicidality, a higher level of substance abuse,

cigarette and alcohol consumption?” said Holly G. Prigerson, associate professor

of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for

Psycho-oncology and Palliative Care Research at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

in Boston. “Yes, yes and yes, over and above depression; they’re better

predictors of those things.”

In an age when activities like compulsive shopping are viewed as disorders, the

subject of grief is especially sensitive. Deeply bereaved people are often

reluctant to talk about their sorrow, and when they do, they are insulted by the

use of terms like disorder or addiction. Grief, after all, is noble — emblematic

of the deep love between parents and children, spouses and even friends. Our

sorrows, the poets tell us, make us human; would proper therapy have denied us

Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”?

Diagnosing a deeper form of grief, however, is not about taking away anyone’s

sorrow. “We don’t get rid of suffering in our treatment,” Dr. Shear said. “We

just help people come to terms with it more quickly.”

“Personally, if it were me,” she added, “I would want that help.”

After a Death, the Pain

That Doesn’t Go Away, NYT, 29.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/29/health/29grief.html

Job Losses,

Early Retirements

Hurt Social Security

September 28, 2009

Filed at 2:32 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Big job losses and a spike in early retirement claims from

laid-off seniors will force Social Security to pay out more in benefits than it

collects in taxes the next two years, the first time that's happened since the

1980s.

The deficits -- $10 billion in 2010 and $9 billion in 2011 -- won't affect

payments to retirees because Social Security has accumulated surpluses from

previous years totaling $2.5 trillion. But they will add to the overall federal

deficit.

Applications for retirement benefits are 23 percent higher than last year, while

disability claims have risen by about 20 percent. Social Security officials had

expected applications to increase from the growing number of baby boomers

reaching retirement, but they didn't expect the increase to be so large.

What happened? The recession hit and many older workers suddenly found

themselves laid off with no place to turn but Social Security.

''A lot of people who in better times would have continued working are opting to

retire,'' said Alan J. Auerbach, an economics and law professor at the

University of California, Berkeley. ''If they were younger, we would call them

unemployed.''

Job losses are forcing more retirements even though an increasing number of

older people want to keep working. Many can't afford to retire, especially after

the financial collapse demolished their nest eggs.

Some have no choice.

Marylyn Kish turns 62 in December, making her eligible for early benefits. She

wants to put off applying for Social Security until she is at least 67 because

the longer you wait, the larger your monthly check.

But she first needs to find a job.

Kish lives in tiny Concord Township in Lake County, Ohio, northeast of

Cleveland. The region, like many others, has been hit hard by the recession.

She was laid off about a year ago from her job as an office manager at an

employment agency and now spends hours each morning scouring job sites on the

Internet. Neither she nor her husband, Raymond, has health insurance.

''I want to work,'' she said. ''I have a brain and I want to use it.''

Kish is far from alone. The share of U.S. residents in their 60s either working

or looking for work has climbed steadily since the mid-1990s, according to data

from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This year, more than 55 percent of people

age 60 to 64 are still in the labor force, compared with about 46 percent a

decade ago.

Kish said her husband already gets early benefits. She will have to apply, too,

if she doesn't soon find a job.

''We won't starve,'' she said. ''But I want more than that. I want to be able to

do more than just pay my bills.''

Nearly 2.2 million people applied for Social Security retirement benefits from

start of the budget year in October through July, compared with just under 1.8

million in the same period last year.

The increase in early retirements is hurting Social Security's short-term

finances, already strained from the loss of 6.9 million U.S. jobs. Social

Security is funded through payroll taxes, which are down because of so many lost

jobs.

The Congressional Budget Office is projecting that Social Security will pay out

more in benefits than it collects in taxes next year and in 2011, a first since

the early 1980s, when Congress last overhauled Social Security.

Social Security is projected to start generating surpluses again in 2012 before

permanently returning to deficits in 2016 unless Congress acts again to shore up

the program. Without a new fix, the $2.5 trillion in Social Security's trust

funds will be exhausted in 2037. Those funds have actually been spent over the

years on other government programs. They are now represented by government

bonds, or IOUs, that will have to be repaid as Social Security draws down its

trust fund.

President Barack Obama has said he would like to tackle Social Security next

year.

''The thing to keep in mind is that it's unlikely we are going to pull out (of

the recession) with a strong recovery,'' said Kent Smetters, an associate

professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. ''These deficits

may last longer than a year or two.''

About 43 million retirees and their dependents receive Social Security benefits.

An additional 9.5 million receive disability benefits. The average monthly

benefit for retirees is $1,100 while the average disability benefit is about

$920.

The recession is also fueling applications for disability benefits, said Stephen

C. Goss, the Social Security Administration's chief actuary. In a typical year,

about 2.5 million people apply for disability benefits, including Supplemental

Security Income. Applications are on pace to reach 3 million in the budget year

that ends this month and even more are expected next year, Goss said.

A lot of people who had been working despite their disabilities are applying for

benefits after losing their jobs. ''When there's a bad recession and we lose 6

million jobs, people of all types are going to be part of that,'' Goss said.

Nancy Rhoades said she dreads applying for disability benefits because of her

multiple sclerosis. Rhoades, who lives in Orange, Va., about 75 miles northwest

of Richmond, said her illness is physically draining, but she takes pride in

working and caring for herself.

In June, however, her hours were cut in half -- to just 10 a week -- at a

community services organization. She lost her health benefits, though she is

able to buy insurance through work, for about $530 a month.

''I've had to go into my retirement annuity for medical costs,'' she said.

Her husband, Wayne, turned 62 on Sunday, and has applied for early Social

Security benefits. He still works part time.

Nancy Rhoades is just 56, so she won't be eligible for retirement benefits for

six more years. She's pretty confident she would qualify for disability

benefits, but would rather work.

''You don't think of things like this happening to you,'' she said. ''You want

to be in a position to work until retirement, and even after retirement.''

------

On the Net:

Social Security retirement planner:

http://www.ssa.gov/retire2/retirechart.htm

Congressional Budget Office:

http://tinyurl.com/ydgrl5d

Job Losses, Early

Retirements Hurt Social Security, NYT, 28.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/09/28/us/politics/AP-US-Social-Security-Early-Retirements.html

A Burst of Technology,

Helping the Blind to See

September 27, 2009

The New York Times

By PAM BELLUCK

Blindness first began creeping up on Barbara Campbell when she was a

teenager, and by her late 30s, her eye disease had stolen what was left of her

sight.

Reliant on a talking computer for reading and a cane for navigating New York

City, where she lives and works, Ms. Campbell, now 56, would have been thrilled

to see something. Anything.

Now, as part of a striking experiment, she can. So far, she can detect burners

on her stove when making a grilled cheese, her mirror frame, and whether her

computer monitor is on.

She is beginning an intensive three-year research project involving electrodes

surgically implanted in her eye, a camera on the bridge of her nose and a video

processor strapped to her waist.

The project, involving patients in the United States, Mexico and Europe, is part

of a burst of recent research aimed at one of science’s most-sought-after holy

grails: making the blind see.

Some of the 37 other participants further along in the project can differentiate

plates from cups, tell grass from sidewalk, sort white socks from dark,

distinguish doors and windows, identify large letters of the alphabet, and see

where people are, albeit not details about them.

Linda Morfoot, 65, of Long Beach, Calif., blind for 12 years, says she can now

toss a ball into a basketball hoop, follow her nine grandchildren as they run

around her living room and “see where the preacher is” in church.

“For someone who’s been totally blind, this is really remarkable,” said Andrew

P. Mariani, a program director at the National Eye Institute. “They’re able to

get some sort of vision.”

Scientists involved in the project, the artificial retina, say they have plans

to develop the technology to allow people to read, write and recognize faces.

Advances in technology, genetics, brain science and biology are making a goal

that long seemed out of reach — restoring sight — more feasible.

“For a long time, scientists and clinicians were very conservative, but you have

to at some point get out of the laboratory and focus on getting clinical trials

in actual humans,” said Timothy J. Schoen, director of science and preclinical

development for the Foundation Fighting Blindness. Now “there’s a real push,” he

said, because “we’ve got a lot of blind people walking around, and we’ve got to

try to help them.”

More than 3.3 million Americans 40 and over, or about one in 28, are blind or

have vision so poor that even with glasses, medicine or surgery, everyday tasks

are difficult, according to the National Eye Institute, a federal agency. That

number is expected to double in the next 30 years. Worldwide, about 160 million

people are similarly affected.

“With an aging population, it’s obviously going to be an increasing problem,”

said Michael D. Oberdorfer, who runs the visual neuroscience program for the

National Eye Institute, which finances several sight-restoration projects,

including the artificial retina. Wide-ranging research is important, he said,

because different methods could help different causes of blindness.

The approaches include gene therapy, which has produced improved vision in

people who are blind from one rare congenital disease. Stem cell research is

considered promising, although far from producing results, and other studies

involve a light-responding protein and retinal transplants.

Others are implanting electrodes in monkeys’ brains to see if directly

stimulating visual areas might allow even people with no eye function to see.

And recently, Sharron Kay Thornton, 60, from Smithdale, Miss., blinded by a skin

condition, regained sight in one eye after doctors at the University of Miami

Miller School of Medicine extracted a tooth (her eyetooth, actually), shaved it

down and used it as a base for a plastic lens replacing her cornea.

It was the first time the procedure, modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis, was

performed in this country. The surgeon, Dr. Victor L. Perez, said it could help

people with severely scarred corneas from chemical or combat injuries.

Other techniques focus on delaying blindness, including one involving a capsule

implanted in the eye to release proteins that slow the decay of light-responding

cells. And with BrainPort, a camera worn by a blind person captures images and

transmits signals to electrodes slipped onto the tongue, causing tingling

sensations that a person can learn to decipher as the location and movement of

objects.

Ms. Campbell’s artificial retina works similarly, except it produces the

sensation of sight, not tingling on the tongue. Developed by Dr. Mark S.

Humayun, a retinal surgeon at the University of Southern California, it drew on

cochlear implants for the deaf and is partly financed by a cochlear implant

maker.

It is so far being used in people with retinitis pigmentosa, in which

photoreceptor cells, which take in light, deteriorate.

Gerald J. Chader, chief scientific officer at the University of Southern

California’s Doheny Retinal Institute, where Dr. Humayun works, said it should

also work for severe cases of age-related macular degeneration, the major cause

of vision loss in older people.

With the artificial retina, a sheet of electrodes is implanted in the eye. The

person wears glasses with a tiny camera, which captures images that the

belt-pack video processor translates into patterns of light and dark, like the

“pixelized image we see on a stadium scoreboard,” said Jessy D. Dorn, a research

scientist at Second Sight Medical Products, which produces the device,

collaborating with the Department of Energy. (Other research teams are

developing similar devices.)

The video processor directs each electrode to transmit signals representing an

object’s contours, brightness and contrast, which pulse along optic neurons into

the brain.

Currently, “it’s a very crude image,” Dr. Dorn said, because the implant has

only 60 electrodes; many people see flashes or patches of light.

Brian Mech, Second Sight’s vice president for business development, said the

company was seeking federal approval to market the 60-electrode version, which

would cost up to $100,000 and might be covered by insurance. Also planned are

200- and 1,000-electrode versions; the higher number might provide enough

resolution for reading. (Dr. Mech said a maximum electrode number would

eventually be reached because if they are packed too densely, retinal tissue

could be burned.)

“Every subject has received some sort of visual input,” he said. “There are

people who aren’t extremely impressed with the results, and other people who

are.” Second Sight is studying what affects results, including whether practice

or disease characteristics influence the brain’s ability to relearn how to

process visual signals.

People choose when to use the device by turning their camera on. Dean Lloyd, 68,

a Palo Alto, Calif., lawyer, was “pretty disappointed” when he started in 2007,

but since his implant was adjusted so more electrodes responded, is “a lot more

excited about it,” he said. He uses it constantly, seeing “borders and

boundaries” and flashes from highly reflective objects, like glass, water or

eyes.

With Ms. Morfoot’s earlier 16-electrode version, which registers objects as

horizontal lines, she climbed the Eiffel Tower and “could see all the lights of

the city,” she said. “I can see my hand when I’m writing. At Little League

games, I can see where the catcher, batter and umpire are.”

Kathy Blake, 58, of Fountain Valley, Calif., said she mainly wanted to help

advance research. But she uses it to sort laundry, notice cars and people, and

on the Fourth of July, to “see all the fireworks,” she said.

Ms. Campbell, a vocational rehabilitation counselor for New York’s Commission

for the Blind and Visually Handicapped, has long been cheerfully

self-sufficient, traveling widely from her fourth-floor walk-up, going to the

theater, babysitting for her niece in North Carolina.

But little things rankle, like not knowing if clothes are stained and needing

help shopping for greeting cards. Everything is a “gray haze — like being in a

cloud,” she said. The device will not make her “see like I used to see,” she

said. “But it’s going to be more than what I have. It’s not just for me — it’s

for so many other people that will follow me.”

Ms. Campbell’s “realistic view of her vision” and willingness to practice are a

plus, said Aries Arditi, senior fellow in vision science at Lighthouse

International, a nonprofit agency overseeing her weekly training, which includes

practice moving her head so the camera captures images and interpreting light as

objects.

“In 20 years, people will think it’s primitive, like the difference between a

Model T and a Ferrari,” said Dr. Lucian Del Priore, an ophthalmology surgeon at

New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center, who implanted

Ms. Campbell’s electrodes. “But the fact is, the Model T came first.”

Ms. Campbell would especially like to see colors, but, for now, any color would

be random flashes, Dr. Arditi said.

But she saw circular lights at a restaurant, part of a light installation at an

art exhibition. “There’s a lot to learn,” she said. Still, “I’m, like, really

seeing this.”

A Burst of Technology,

Helping the Blind to See, NYT, 27.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/27/health/research/27eye.html

Atlanta Judge Rules

Dialysis Unit Can Be Closed

September 26, 2009

The New York Times

By KEVIN SACK

ATLANTA — Uninsured dialysis patients who could be cut off from their

life-sustaining care lost a court challenge on Friday when a judge ruled that

Grady Memorial Hospital could close its outpatient dialysis clinic. But the

hospital gave the patients a temporary reprieve.

Ruling largely on technical grounds, a state court judge dissolved the

restraining order that prevented last weekend’s scheduled closing of the clinic

at Grady, the Atlanta region’s safety net hospital. The hospital, which is

deeply in debt, quickly announced it would close the clinic within a week. It

agreed, however, to pay for up to three months of dialysis at private clinics

for the 51 patients who will be dislocated.

Grady will continue to assist the indigent patients, many of them illegal

immigrants, in seeking care in their home countries or in other states where

they may qualify for emergency Medicaid coverage.

Lawyers and advocates for the Grady dialysis patients had asked in negotiating

sessions that the hospital provide a longer transition period. Grady’s senior

vice president, Matt Gove, said he could not speculate about whether the

hospital would extend its financial assistance beyond three months to patients

unable to make arrangements.

“The hospital, along with the patient, each bears some responsibility in doing

everything we can to find a long-term solution,” Mr. Gove said.

Federal law generally prohibits coverage of illegal immigrants by Medicaid and

Medicare (which pays for dialysis for citizens regardless of age). Some states —

but not Georgia — allow those immigrants to use Medicaid dollars in emergency

situations, potentially including dialysis. Legal immigrants must wait five

years before qualifying for benefits.

In the Atlanta region, that has made Grady, which accepts all patients

regardless of immigration status or ability to pay, the provider of last resort

for many illegal and uninsured patients. The taxpayer-supported hospital

estimates the dialysis clinic will lose $2 million this year. Mr. Gove said he

could not project how much the three-month extension might cost.

Lindsay R. Jones, the lawyer for the patients, called the order Friday by Judge

Ural D. Glanville of Fulton County Superior Court “an angry, punitive decision.”

“At least 51 patients had their life support system unplugged today under the

authorization of this judge,” Mr. Jones said.

He said he planned to refile his case in Judge Glanville’s court on Monday after

addressing its technical problems. He said he hoped to persuade the judge to

hear the stories of some of the dialysis patients who accompanied him to a

hearing on Wednesday but were not allowed to testify.

Mr. Jones said he did not expect a markedly different result, but hoped to

create a record that might be used in a federal court filing that he was

considering.

Judge Glanville ruled that Mr. Jones’s class-action complaint had been

improperly filed because, among other reasons, it lacked signatures from the two

patients listed as plaintiffs. But the judge went further by writing that even

if the case had been properly filed it would be unlikely to succeed on the

merits.

“As it relates to the receipt of medical treatment, the court is unpersuaded at

this time that plaintiffs have a constitutional right to the sought-after

relief,” Judge Glanville wrote.

Atlanta Judge Rules

Dialysis Unit Can Be Closed, NYT, 27.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/26/health/policy/26grady.html

For First Time,

AIDS Vaccine Shows Some Success

September 25, 2009

The New York Times

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr.

Scientists said Thursday that a new AIDS vaccine, the first ever declared to

protect a significant minority of humans against the disease, would be studied

to answer two fundamental questions: why it worked in some people but not in

others, and why those infected despite vaccination got no benefit at all.

The vaccine — known as RV 144, a combination of two genetically engineered

vaccines, neither of which had worked before in humans — was declared a

qualified success after a six-year clinical trial on more than 16,000 volunteers

in Thailand. Those who were vaccinated became infected at a rate nearly

one-third lower than the others, the sponsors said Thursday morning.

“I don’t want to use a word like ‘breakthrough,’ but I don’t think there’s any

doubt that this is a very important result,” said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the

director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is

one of the trial’s backers.

“For more than 20 years now, vaccine trials have essentially been failures,” Dr.

Fauci said. “Now it’s like we were groping down an unlit path, and a door has

been opened. We can start asking some very important questions.”

It will still, however, take years of work before a vaccine that could end the

epidemic, which has killed about 25 million people, can even be contemplated.

“We often talk about whether a vaccine is even possible,” said Mitchell Warren,

the executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, or AVAC. “This is

not the vaccine that ends the epidemic and says, ‘O.K., let’s move on to

something else.’ But it’s a fabulous new step that takes us in a new direction.”

In which direction is still unknown. No one — including the researchers from the

United States Army, the National Institutes of Health, the Thai Ministry of

Public Health and two vaccine companies that tested the vaccine — knows why the

vaccine gave even its weak indicator of success.

Experts generally disdain vaccines that do not protect at least 70 to 80 percent

of those getting them. And this vaccine did not lower the viral loads of people

who were vaccinated but caught the virus anyway, which was baffling because even

mismatched vaccines usually do that.

Simply repeating the trial to confirm the results would be pointless, experts

agreed.

The trial, the largest AIDS vaccine trial in history, cost $105 million and

followed 16,402 Thai volunteers.

The men and women ages 18 to 30 were recruited from two provinces southeast of

the capital, Bangkok, from the general population rather than from high-risk

groups like drug injectors or sex workers. Half got six doses of two different

vaccines; half were given placebos.

For ethical reasons, all were offered condoms, taught how to avoid infection and

promised lifelong antiretroviral treatment if they got AIDS. They were then

regularly tested for three years; 74 of those who got placebos became infected,

but only 51 of those who got the vaccines did.

Although the difference was a mere 23 people, Col. Jerome H. Kim, a physician

and the manager of the Army’s H.I.V. vaccine program, said it was statistically

significant and meant that the vaccine was 31.2 percent effective.

The results were surprising because both vaccines, one from the French company

Sanofi-Aventis and one developed by Genentech but now licensed to Global

Solutions for Infectious Diseases, a nonprofit health group, had failed when

used individually.

“This came out of the blue,” said Chris Viehbacher, Sanofi’s chief executive.

Even 31 percent protection “was at least twice as good as our own internal

experts were predicting,” he added.

In 2004, there was so much skepticism about the trial just after it began that

22 top AIDS researchers published an editorial in Science magazine suggesting

that it was a waste of money.

One conclusion from the surprising result, said Alan Bernstein, head of the

Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, an alliance of organizations pursuing a vaccine,

“is that we’re not doing enough work in humans.”

Instead of going back to mice or monkeys, he said, different new variants on the

two vaccines could be tried on a few hundred people in several countries.

This vaccine was designed to combat the most common strain of the virus in

Southeast Asia, so it would have to be modified for the strains circulating in

Africa and the United States.

Sanofi’s vaccine, Alvac-HIV, is a canarypox virus with three AIDS virus genes

grafted onto it. Variations of it were tested in several countries; it was safe

but not protective. The other vaccine, Aidsvax, was originally made by Genentech

and contains a protein found on the surface of the AIDS virus; it is grown in a

broth of hamster ovary cells. It was tested in Thai drug users in 2003 and in

gay men in North America and Europe but failed.

In 2007, two trials of a Merck vaccine in about 4,000 people were stopped early;

it not only failed to work but for some men also seemed to increase the risk of

infection.

Combining Alvac and Aidsvax was simply a hunch: if one was designed to create

antibodies and the other to alert white blood cells, might they work together?

One puzzling result — those who became infected had as much virus in their blood

whether they got the vaccine or a placebo — suggests that RV 144 does not

produce neutralizing antibodies, as most vaccines do, Dr. Fauci said. Antibodies

are Y-shaped proteins formed by the body that clump onto invading viruses,

blocking the surface spikes with which they attach to cells and flagging them

for destruction.

Instead, he theorized, it might produce “binding antibodies,” which latch onto

and empower effector cells, a type of white blood cell attacking the virus.

Therefore, he said, it might make sense to screen all the stored Thai blood

samples for binding antibodies.

“The humbling prospect of this,” he said, “is that we may not even be measuring

the critical parameter. It may be something you don’t normally associate with

protection.”

Dr. Lawrence Corey, the principal investigator for the HIV Vaccine Trials

Network, who was not part of the RV 144 trial, said new work on weakened

versions of the smallpox vaccine had produced better pox “spines” that could be

substituted for the canarypox. New trials, he added, could be faster and smaller

if they were done in African countries where AIDS is more common than in

Thailand.

For First Time, AIDS Vaccine Shows Some

Success, NYT, 25.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/25/health/research/25aids.html

Immigrants Cling to Fragile Lifeline

at Safety-Net Hospital

September 24, 2009

The New York Times

By KEVIN SACK

ATLANTA — If Grady Memorial Hospital succeeds in closing its outpatient

dialysis clinic, Tadesse A. Amdago, a 69-year-old immigrant from Ethiopia, said

he would begin “counting the days until I die.” Rosa Lira, 78, a permanent

resident from Mexico, said she also assumed she “would just die.” Another woman,

a 32-year-old illegal immigrant from Honduras, said she could only hope to make

it “back to my country to die.”

The patients, who have relied for years on Grady’s free provision of dialysis to

people without means, said they had no other options to obtain the care that is

essential to their survival. But the safety-net hospital, after years of failed

efforts to drain its red ink, is not backing away from what its chairman, A. D.

Correll, calls a “gut-wrenching decision”: closing the clinic this month.

The sides confronted each other in state court on Wednesday morning as lawyers

for the patients sought to keep the clinic open until other arrangements for

dialysis could be secured. Dialysis patients and their families packed the

benches and 60-year-old Nelson Tabares, a seriously ill illegal immigrant from

Honduras, was wheeled into court in a portable bed.

Despite a judge’s urging that the two sides negotiate a solution Wednesday,

there was no agreement by the end of the day on how to go forward. For the time

being, a restraining order keeping the clinic open stands. The judge is

considering whether to extend it.

The dialysis unit on Grady’s ninth floor might as well be ground zero for the

national health care debate. It is there that many of the ills afflicting

American health care intersect: the struggle of the uninsured, the strain of

providing uncompensated care, the inadequacy of government support, and the

dilemma posed by treating illegal immigrants.

Grady is one of many public hospitals that have been battered by the recession

as the number of uninsured has mounted. New York City’s public hospital system

is eliminating 400 positions and closing some children’s mental health programs,

pharmacies and clinics. University Medical Center in Las Vegas has closed its

mammography center and outpatient oncology clinic.

“It comes down to which service do you need to keep open,” said Larry S. Gage,

president of the National Association of Public Hospitals. “You try your hardest

to cut back on services that are going to be available elsewhere in the

community.”

Public hospital officials are concerned that the health care legislation being

negotiated in Washington could worsen their plight before making it better.

Under bills traveling through both houses of Congress, as the number of

uninsured declines there would be commensurate reductions in Medicaid subsidies

to hospitals that provide large amounts of uncompensated care.

At Grady, about four in 10 patients are uninsured, and an additional 25 percent

are insured by Medicaid, which reimburses at rates so low they often do not

cover actual costs. As a result, the hospital lost $33.5 million last year, with

the dialysis clinic accounting for about $2 million of that total, said Denise

R. Williams, the hospital’s executive vice president.

Nonetheless, as a taxpayer-supported hospital with the mission of serving the

indigent, Grady is expected to take all comers in need of emergency care, like

dialysis. Treatment there does not depend on a patient’s insurance or

immigration status.

The hospital has been encouraging some of the dialysis patients to move to other

states or back to their home countries, offering to defray some costs.

Hospital officials estimate that two-thirds of the outpatient clinic’s roughly

90 patients are illegal immigrants. They do not qualify for Medicare, which

covers dialysis regardless of a patient’s age, and they are excluded in Georgia

from Medicaid and other government insurance programs. Legal immigrants face a

five-year waiting period before becoming eligible. That leaves Grady to absorb

costs of up to $50,000 a year per dialysis patient, some of whom have availed

themselves of the thrice-weekly treatments for years.

After years of fiscal desperation and management turmoil at Grady, Atlanta

business leaders stepped in last year to force a restructuring, from a

quasi-governmental authority to a nonprofit corporate board. In response, the

Robert W. Woodruff Foundation pledged $200 million over four years to replace

dilapidated beds and modernize computers. A $20 million gift from Bernie Marcus,

a founder of Home Depot, is helping to update the emergency department, which

provides regional trauma services.

But the hospital’s operating deficits have continued. Grady’s senior vice

president, Matt Gove, estimated that its uncompensated care would grow by $50

million this year, up 25 percent. The new nonprofit board eliminated 150 jobs

this year, closed an underused primary care clinic and began charging higher

fees to patients who live outside of the two counties that support Grady with

direct appropriations.

The closing of the outpatient dialysis clinic was recommended by consultants in

2007, who said that equipment was outmoded, that most hospitals did not provide

outpatient dialysis and that Atlanta had scores of commercial dialysis centers.

When the hospital’s chief executive at the time tried to shut it down, the

resulting firestorm helped prompt his dismissal.

This July, the new board voted to try again. The hospital gave patients a

month’s notice of the scheduled Sept. 19 closing, and vowed to assist them in

finding local dialysis providers, relocating elsewhere and qualifying for public

insurance. “We committed that not a single person would be left behind,” Mr.

Correll wrote in a newspaper advertisement published on Sunday.

About a third of the patients have been successfully moved, including several

illegal immigrants who returned to Mexico with the hospital’s financial help,

Mr. Gove said. But others have said they have no place to go, have no means to

pay for dialysis or are too ill to travel.

The female illegal immigrant from Honduras, who has a 7-year-old son, said her

parents live more than a four-hour drive from the nearest dialysis center, in

Tegucigalpa. She is mindful that her sister died from a stroke while being

driven to a hospital there. She said she had no money to pay for dialysis

because she was too weary from her kidney condition to hold down a job.

“I feel like they are trying to get rid of me because I don’t work,” she said,

her eyes tearing. “But being sick is not my fault.”

Samuel Tabares, who rolled his father into court in his bed, said his father,

who was paralyzed by a stroke, would probably not survive the strain of

relocation or repeated trips to the emergency room in search of treatment.

“They’re treating the closing of this clinic like it’s the closing of a dental

clinic,” Mr. Tabares said, “as if people’s lives don’t depend on it.”

Immigrants Cling to Fragile Lifeline at

Safety-Net Hospital, NYT, 24.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/24/health/policy/24grady.html

Forty Years' War

Where Cancer Progress Is Rare,

One Man Says No

September 16, 2009

The New York Times

By GARDINER HARRIS

Politicians and researchers have predicted for nearly four decades that a

cure for cancer is near, but cancer death rates have hardly budged and most new

cancer drugs cost a fortune while giving patients few, if any, added weeks of

life. For this collective failure, the man atop the nation’s regulatory agency

for new cancer drugs increasingly — and supporters say unfairly — gets the

blame: Dr. Richard Pazdur.

Patient advocates have called Dr. Pazdur, director of the Food and Drug

Administration’s cancer drug office, a murderer, conservative pundits have

vilified him as an obstructionist bureaucrat, and guards are now posted at the

agency’s public cancer advisory meetings to protect him and other committee

members.

“The industry is not producing that many good drugs, so now they’re looking for

scapegoats in Rick Pazdur and the F.D.A.,” said Ira S. Loss, who follows the

drug industry for Washington Analysis, a service for investors.

In 10 years at the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Pazdur, 57, has helped to

loosen approval standards for cancer medicines and made it easier for dying

patients to get experimental drugs. But he demands that drug makers prove with

near certainty that their products are beneficial, a requirement that he

repeated at a public advisory hearing on Sept. 1 in the slow, loud tones of

someone disciplining a dog. After he spoke, the committee of experts voted to

reject both drugs.

Critics say that Dr. Pazdur’s resolve has cost thousands of lives and set back

the pace of discoveries.

“Patients are right to be angry and frustrated with Richard Pazdur,” said Steven

Walker, co-founder of the Abigail Alliance, a patient advocacy group. “He is a

dinosaur.”

But neither the controversies swirling about him nor his years as an oncologist

treating terminal patients have dented Dr. Pazdur’s naturally sunny disposition.

He laughs like Charles Nelson Reilly, eats like Gandhi and likens his tenure at

the drug administration to that of a Roman Catholic priest from the 1960s who

had to translate the Latin liturgy into plain language.

“You can’t win in this job,” Dr. Pazdur said in an interview in his office. “If

you approve a drug, they accuse you of lowering standards. And if you don’t

approve it, you’re the worst thing since the Nazi death camps and should be

killed.”

Whether Dr. Pazdur has struck the right balance between hope and certainty has

enormous consequences for patients and industry. Cancer is the second-leading

cause of death in the United States; more than 562,000 people are expected to

die of it this year.

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies are testing more than 860 new cancer

medicines — more than in any other disease category, according to manufacturers.

Because patients are desperate and insurers are often forced by law to pay,

prices are soaring, making cancer medicines among the best ways for drug makers

to make money. But cancer has proven difficult to crack, leading to frustration

among executives and advocates who wonder why the Food and Drug Administration

is not approving more drugs.

No cancer medicines can be sold to or even tested on people without the

imprimatur of Dr. Pazdur and his staff of about 150 oncologists, toxicologists

and other specialists. But pressure from advocacy groups and cancer researchers

frustrated with failure have led the agency to abandon many of the usual

approval requirements.

Federal law requires that the agency demand two “well controlled” trials before

approving a drug; in cancer, the Food and Drug Administration is often satisfied

with just one. With many experimental drugs, the agency demands trials with

thousands of patients, while for cancer, it has accepted studies with a few

dozen.

Before Dr. Pazdur’s arrival, the agency largely insisted that drug makers prove

that their products extended life. Companies did this by giving the drug to one

group of patients, providing a placebo or an older drug to another group and

then seeing which group lived longer. But some cancers take a long time to kill,

making survival trials lengthy and expensive.

So the drug administration under Dr. Pazdur’s leadership increasingly allowed

some studies to track a drug’s effect with X-rays. If scans showed that tumors

grew less rapidly, the drug could be approved.

Dr. Pazdur pressed for the changes because, he said, the growing number of

approved cancer medicines made determining whether any one delayed death

increasingly difficult. Many patients now cycle through several medicines before

dying. And some drugs that have not been proven to extend life may delay more

serious symptoms and medical interventions, he said.

For instance, the drug administration initially rejected oxaliplatin because no

trial at the time proved that it delayed death. But the agency finally relented

in 2002 — years after the drug’s approval in Europe — because scans showed that

it postponed tumor growth. Oxaliplatin is now commonly used to combat colorectal

cancer.

Criticizing Changes

Some patient advocates — mostly from older, more established organizations —

bemoan these changes because even if a drug shrinks tumors, it may do nothing to

delay death or improve patients’ last days. And because so many cancer medicines

have toxic side effects and high prices, drugs that have no proven benefit may

actually be harmful to patients’ health and economic well-being.

These advocates point to mistakes like toxic chemotherapy with bone marrow

transplants in breast cancer, which in the 1980s and 1990s increased the

suffering of nearly 30,000 women before studies finally showed that it was

ineffective. When in doubt, the drug administration should not approve, they

say.

“We want drugs that prolong survival, not drugs that just improve a test

result,” said Frances M. Visco, president of the National Breast Cancer

Coalition.

To others — mostly newer, more aggressive patient organizations — the F.D.A.’s

cancer group under Dr. Pazdur’s leadership has not lowered standards or sped

approvals nearly enough. If there is any hint that a drug works, dying patients

— many of whom have run out of other options — should be allowed to buy them,

they said.

And some cancer specialists say that Dr. Pazdur, after pushing for years to

lower approval standards, has toughened them recently after being criticized for

approving drugs that were later shown to have few benefits.

“I’m worried there’s been a change in his thinking that could be adverse for the

field,” said Dr. Bruce A. Chabner, clinical director of the Massachusetts

General Hospital Cancer Center and a member of the board of directors of

PharmaMar, a Spanish biotech company whose drug Yondelis is approved in Europe

but was rejected in July by the F.D.A.’s cancer advisory board after a critical

introduction by Dr. Pazdur.

Little of this controversy surrounding Dr. Pazdur affects the development of

truly powerful medicines. In 2001, his agency took just 11 weeks to approve

Gleevec, which has miraculous effects on a form of leukemia. But when drugs have

marginal benefits, figuring out whether they work is controversial and time

consuming.

Taking a Drug to the F.D.A.

Many of the recent rejects have come from small biotechnology companies for

which a single F.D.A. approval can be the difference between fiscal calamity and

vast profits. On Sept. 1, tiny Vion Pharmaceuticals took its leukemia drug

Onrigin to a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee for consideration.

One clinical trial found that Onrigin increased deaths threefold compared with a

placebo. The drug administration told the company in meetings in 2004 and 2006

that another trial was so poorly designed that it was unlikely to pass muster.

Vion persisted.

During the company’s presentation to the advisory committee, Dr. Pazdur seemed

at times visibly pained — grimacing or shaking his head. When patients taken to

the meeting by Vion spoke about Onrigin’s benefits, he turned away. (“Only

patients who benefit from the drugs are brought to the meetings, not those who

are harmed or get nothing,” he explained later.) He reminded the committee, “We

only have one randomized trial here which shows an increase in death.”

The committee voted 13 to 0 to require a new study. Vion executives would not

comment.

Some small companies seeking approval of a drug have waged public campaigns with

the help of investors and advocacy groups that sometimes lead to vicious attacks

on Dr. Pazdur. Take the case of Xcytrin, a brain cancer medicine made by

Pharmacyclics of Sunnyvale, Calif. After a critical study failed to show that

the drug worked, the company’s chief executive at the time, Dr. Richard Miller,

blamed doctors at a hospital in France.

“They got a very negative result there, and it really skewed the data,” Dr.

Miller said in an interview.

He lobbied top F.D.A. officials to approve the drug anyway. They refused. He

became a prominent agency critic, writing four opinion columns in The Wall

Street Journal in 2007 arguing that the agency was keeping vital treatments from

dying patients.

Dr. Miller did not make public the drug agency’s reasons for rejecting Xcytrin

and, because the law prevents the agency from discussing drug rejections, Dr.

Pazdur remained mum.

A year ago, Dr. Miller was replaced as chief executive at Pharmacyclics by

Robert W. Duggan. In an interview, Mr. Duggan said that the Xcytrin study was

flawed and that the drug administration was right to reject the drug.

“It’s not just one hospital mishandling the data — that’s false,” said Mr.

Duggan, who described the trial’s results as a “dog’s breakfast” of confusing

signals. Biotech executives often blame the drug administration for their own

failures so they can continue to raise money from investors, Mr. Duggan said.

Dr. Miller, who is raising money for a new company, responded, “I think Mr.

Duggan is making nice to the F.D.A.”

Tony Fiorino, president and chief executive of EnzymeRx, in Paramus, N.J., said

that biotech executives were often former scientists who believed so deeply in

their products that “it’s an ecstatic experience.” When the drug administration

rejects their application, these executives have every incentive, he said, to

“go ballistic on the agency.”

“You’re going to pull out all the stops,” Mr. Fiorino said. “This is your one

lottery ticket.”

And it is not just executives behind the attacks. Melvin Flores, an oxygen

technician from Lowell, Ark., sent several e-mail messages last year to Dr.

Pazdur, one of which said, “You’ve murdered enough innocent people already —

enough is enough.”

Mr. Flores invested in a company whose cancer medicine did not get approved,

pummeling its shares and depriving patients of a lifesaver, he said in an

interview. “It’s a Holocaust that has happened,” he said.

Besides singling out Dr. Pazdur’s e-mail box, advocates have put his name on

advertisements on city buses in the Washington area, sued him and shouted his

name at protests. But Dr. Pazdur said he and his family had endured far worse.

In Perspective

His grandfather, a Polish immigrant, was crushed to death under a railroad car

in the Great Depression while sweeping up loose corn kernels to feed his family.

With six children, his grandmother remarried, had three more kids and was

widowed again several years later when her second husband died in a construction

accident.

His mother married her first husband two weeks before he shipped out for World

War II; he was killed in the war. Dr. Pazdur’s father, a factory worker for

Standard Oil of Indiana, went blind from glaucoma when Dr. Pazdur was a young

teenager, impoverishing his family anew.

An avid gym cyclist who is greyhound thin, Dr. Pazdur does not eat meat because

he believes that a vegetarian diet will help protect him from cancer, although

the supporting evidence is as thin as vegetable broth. His wife, Mary, said that

when he travels, she buys herself a nice steak.

Dr. Pazdur became intrigued with the Food and Drug Administration while

overseeing drug trials at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

When the cancer job became available, he applied. On his first day, he was

struck by how much the agency resembled the Catholic Church of his childhood.

“We had a door in our old office that was controlled electronically, so someone

had to buzz you in,” Dr. Pazdur said. “We had that same door in my grade school

separating the convent from the school. It was such a secretive world here.”

He set about changing that by reaching out to cancer advocacy and medical

groups. He has held cancer advisory meetings at the annual meeting of the

American Society of Clinical Oncology, the world’s largest body of cancer

scientists. And he began, in conjunction with others, an annual training program

for cancer researchers.

The result is that Dr. Pazdur “has a lot of support within the mainstream cancer

community,” said Dr. Otis W. Brawley, chief medical officer of the American

Cancer Society. In May, the oncologists’ society gave him a special recognition

award for “his outstanding service to the oncology community.”

Dr. Pazdur said that blaming the Food and Drug Administration for the dearth of

new cancer medicines was “like blaming the failures of American education on the

SAT test.”

“We just do the assessments,” he said.

Where Cancer Progress Is

Rare, One Man Says No, NYT, 16.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/16/health/policy/16cancer.html

Slain Abortion Opponent

‘Loved the Controversy’

His Protests Generated

September 14, 2009

The New York Times

By MARY M. CHAPMAN

OWOSSO, Mich. — For at least two decades, in weather good or bad, James

Pouillon would stand for hours at a time around this small, rural town, waving

graphic signs and breaking the idyllic quiet with loud anti-abortion rants.

That is how most residents of Owosso, just outside Flint, said they would

remember Mr. Pouillon, a retired auto worker who was shot to death on Friday

morning while staging a protest here. Others, though, knew him as a good

neighbor and devoted family man who loved to romp with his grandchildren in his

backyard.

On the day he died, Mr. Pouillon, 63, was in front of Owosso High School doing

what he did just about every day, demonstrating and carrying a placard bearing

the word “Life” on one side and an image of an aborted fetus with the word

“Abortion” on the other.

Mr. Pouillon’s death is believed to be the first killing of a person protesting

abortion. And it even caught the attention of President Obama, who on Sunday

called the shooting “deplorable” in a statement. “Whichever side of a public

debate you’re on,” he said, “violence is never the right answer.”

An Owosso truck driver, Harlan J. Drake, has been charged in Mr. Pouillon’s

killing and that of a local businessman, Mike Fuoss. Sara Edwards, the Shiawasee

County chief assistant prosecutor, said the suspect was annoyed by Mr.

Pouillon’s protests, especially when they were near schools.

Mr. Pouillon’s nephew Steven Pouillon, 39, said in a telephone interview from

his home in Owosso that his uncle was a family man “who took care of his own.”

He said his uncle was in good spirits when he last saw him, at a high school

football game on Sept. 4.

Although he said the two of them were not particularly close, Steven Pouillon

remembers hunting and fishing trips together years ago. He said that Mr.

Pouillon’s divorce more than a decade ago “triggered” an increase in his protest

activities.

“He got heavy into it after that,” he said.

Mr. Pouillon was a frequent diner at Greg and Lou’s, a family restaurant in

Owosso. He visited at least twice a week, mostly for breakfast. And he seemed

like a normal guy to Amanda Lange, a waitress there.

“He never pushed that here,” Ms. Lange said of Mr. Pouillon’s views. “He was a

very nice guy. He’d always ask about my family.”

But Tony Young, president of Young Chevrolet, saw another side of Mr. Pouillon,

who sometimes protested outside his dealership. The protests were because Mr.

Pouillon did not like a political candidate Mr. Young supported, Mr. Young said.

“He loved the attention, he loved the controversy,” Mr. Young said, “and he knew

how to get your goat.”

Longtime residents said Mr. Pouillon grew up in Owosso and kept mostly to

himself. He went to work at a Flint plant.

One of those residents, Jimmy Carmody, 54 also linked Mr. Pouillon’s protests to

his divorce.

“I really don’t think he hated abortion as much as he was bitter about the

marriage,” Mr. Carmody said, after shopping at the Farmer’s Market. Mr.

Pouillon’s former wife, Mary Lou, died in a car accident in 2001, a family

member said.

Last Saturday, “the Sign Man,” as many local residents called Mr. Pouillon, was

pelted with fruit by a shopper with whom he was arguing while protesting near

the market. “He’d stand over there with his signs and be cussing customers out,”

Mr. Carmody said. “He became just too in-your-face.”

In the last year or so, Mr. Pouillon’s protests became increasingly erratic.

“You could hear him sometimes making baby noises, or screaming something about

Obama,” Mr. Carmody said.

Mr. Young said that after about three years of protesting outside his

dealership, Mr. Pouillon came in and offered a truce. “ ‘Tony,’ ” Mr. Young said

the exchange began, “if you would just agree that I’m right on my beliefs, I’ll

stop.’

“I just told him, ‘Sure, Jim, you’re right,’ ” Mr. Young said, chuckling. After

that, he said, Mr. Pouillon moved on.

Mr. Young said the last time he saw Mr. Pouillon was at the football game. In

addition to places like City Hall, Mr. Pouillon liked to be where he thought he

could influence young people, he said.

Ms. Edwards said Mr. Pouillon had been arrested before for his activities,

although not in recent years. “He knew his boundaries,” she said. “He always was

on the right of way. He knew where he could stand, basically.”

From most accounts, Mr. Pouillon was not particularly religious, although he did

occasionally attend St. Paul’s Catholic Church in Owosso, residents said. He was

active with area anti-abortion groups. A vigil was held for him Sunday not far

from where he was shot, The Associated Press reported.

On Saturday, a handful of bouquets lay at the corner where Mr. Pouillon was

killed.

The clean, expansive mobile home community where he lived is in a remote area of

Owosso Township surrounded by cornfields and dotted with single-family, mostly

aluminum-sided homes. A dirt-bike racing complex is nearby. The home where Mr.

Pouillon lived is beige with maroon shutters that have heart shapes cut out of

them. The lawn is well manicured, and flags adorn the outside doors. Two of Mr.

Pouillon’s five adult children, his daughter Mary Jo, 26, and his son Lance, 24,

lived with him.

Gary Herald, 33, a computer programmer and Mr. Pouillon’s next-door neighbor for

the last nine years, said he had thought something bad might befall Mr. Pouillon

because of his protesting.

“We used to talk casually as neighbors,” Mr. Herald said, “and one time a few

years ago I told him I thought his signs were gross. He just shrugged and told

me those were his beliefs.”

Steven Pouillon said that his uncle was regularly threatened by residents for

his anti-abortion protests, but that he never took them seriously.

“Everybody talked their smack, but my uncle was never afraid,” he said.

Mr. Pouillon frequently had visitors, Mr. Herald said, adding that he never saw

any anti-abortion activity in the complex. “He was always at softball games

watching his granddaughter play from his old Dodge van. He’d be there

encouraging her.”

Slain Abortion Opponent

‘Loved the Controversy’ His Protests Generated, NYT, 14.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/14/us/14abortion.html

Letters

Putting America on a Healthier Diet

September 12, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Big Food vs. Big Insurance,” by

Michael Pollan (Op-Ed, Sept. 10):

Mr. Pollan rightly contends that health care reform will be ineffective unless

the country’s increasing obesity problem is addressed. But because the food

industry is only part of the problem, reforming it is only part of the solution.

The other part of the problem is the American consumer. While food producers

provide an array of unhealthy fare, how, what and when we eat are personal

choices.

Mr. Pollan praises attempts to tax sugary sodas because these products add empty

calories to our diets, particularly for our youth. Yet sugar-free sodas have

been available and widely consumed for 40 years. The choice is the consumer’s.

If we are to make headway on this issue, we must have comprehensive physical

education and health education in our schools and incentives supporting healthy,

active lifestyles and nutritional food choices for all citizens.

Like all industries, the food producers are driven by their bottom line. Only

when consumers begin to demand healthier food will the industry change.

Anne-Marie Hislop

Davenport, Iowa, Sept. 10, 2009

•

To the Editor:

I applaud Michael Pollan’s recognition that obesity is the “elephant in the

room” in the health care debate, but dissent on his solutions.

Taxing specific products such as soft drinks or creating yet another educational

program will not get the job done. Multiple studies have demonstrated that “fat”

taxes will not appreciably lower obesity rates, while attempts to change

consumer eating behavior have historically come up short.

The real enemy is the number of excess calories available for consumption,

regardless of the source. The only way to slim down this beast is to engage the

food industry.

Rather than alienate or overregulate the industry, my recommendation is to put

into effect tax incentives that would entice food companies to sell fewer

calories. If they cut their calories, they would be rewarded. If they continued

to spew excess calories on the public, they would risk losing favorable tax

treatments.

This approach is well worth discussing. Our nation’s health depends on it.

Henry J. Cardello

Chapel Hill, N.C., Sept. 10, 2009

The writer is a former food industry executive and author of “Stuffed: An

Insider’s Look at Who’s (Really) Making America Fat.”

•

To the Editor:

Eating well and exercising are important, but not necessarily a panacea against

disease.

I am a 55-year-old woman who is slim, eats a healthy organic diet, takes ballet

classes and practices yoga on a weekly basis.

I had breast cancer in 2003 and learned I had Stage 4 tonsil cancer in 2008. My

out-of-the-pocket costs for my recent treatment for tonsil cancer totaled

$15,000.

As part of my follow-up care, I need thousands of dollars of dental work, plus

expensive magnetic resonance imaging every six months for the next three years.

My monthly health insurance premium, for me alone, has gone up to $662.

Michael Pollan is correct in targeting agribusiness for contributing to obesity,

but he does a grave disservice to me, and Americans in general, when he links

the dire consequences of not having strong and meaningful health care reform

with the honorable, but separate, issue of food industry reform.

Francesca Pastine

San Francisco, Sept. 10, 2009

•

To the Editor:

As a big fan of Michael Pollan, I was delighted to read “Big Food vs. Big

Insurance.”

I am 65, look 50, and weigh 10 pounds more than when I graduated from high

school, where I lettered in two sports. I work out three or four times a week,

recently added two weekly yoga classes, take stairs whenever possible and have

no major health issues.

My “diet” is to eat as much as I need, and no more. If my weight is up a little

any morning, I just eat less that day.

My wife and I usually split the massive entrees at restaurants, we eat very

little meat, and our snacks are fruits and nuts. And yes, I indulge — with a

little delicious dark chocolate and low-fat ice cream every day.

I don’t eat junk food or buy the soft drinks and other reconstituted muck that

American agribusiness currently substitutes for real food.

When Americans demand that restaurants and agribusiness put our health first, I

will no longer be unusual.

James G. Goodale

Houston, Sept. 10, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Michael Pollan’s essay on the role of the food industry in contributing to

obesity and associated chronic diseases may have some merit, but only because

too many consumers make poor dietary choices, meal after meal, day after day.

Are we really going to blame the food industry for providing foods we enjoy but

overindulge in? When did personal responsibility go out the window?