|

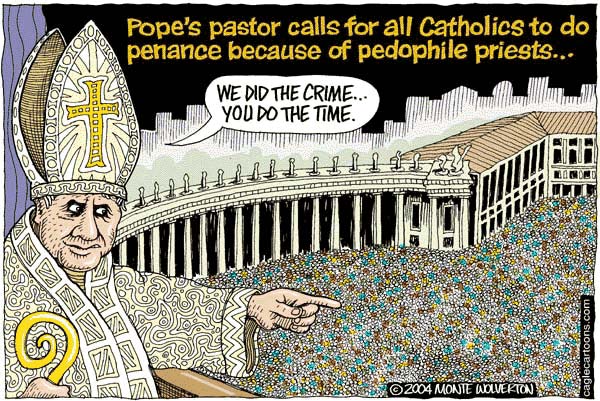

History > 2006 > USA > Faith, Sects (V)

Monte Wolverton

The Wolvertoon Cagle

18.12.2006

http://cagle.msnbc.com/politicalcartoons/PCcartoons/wolverton.asp

Pope Benedict XVI

Faith brings people together

and tears them

apart

Updated 12/28/2006 12:11 PM ET

USA Today

This year offered a window on religious faith

at its most inspirational — as well as ample reminders of ideological conflict

and garden-variety sexual scandals. USA TODAY's Cathy Lynn Grossman looks back:

•Forgiveness. The tiny Amish community of

Nickel Mines, Pa., exemplified forgiveness after a neighbor opened fire on 10

schoolgirls in October, killing five. Their faith teaches submission to the will

of God and compassion to all. So they lived it, quietly, devoutly. While the

world watched in humble awe, mourning parents brought food and comfort to the

killer's family, even as they buried their daughters.

•Apologies. In June, Mel Gibson, director of The Passion of the Christ,

apologized profusely to the Jewish people for an anti-Semitic drunken rant after

a police report leaked out detailing his comments to a Jewish police officer who

stopped him for speeding. And Pope Benedict XVI apologized after angering

Muslims worldwide with an academic speech in September quoting an ancient

emperor who linked Islam and violence. In a visit this month to Turkey, he spoke

well of Islam's moral message in a chaotic world and visited a mosque, only the

second pope to do so.

•Episcopal divide. The split continued to widen between the Episcopal Church,

which approved a gay bishop three years ago, and the Anglican Communion, which

draws most of its global membership from conservative Third World churches.

At its triennial meeting in June, Episcopal lay leaders and clergy elected their

first female president, Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori, a scientist turned

priest who supports gay bishops and gay marriage. Her election drove more of the

most conservative believers, about 10% of parishes and dioceses in the

2.3-million-member U.S. denomination, to withhold contributions. Nearly three

dozen churches, including some of the USA's wealthiest and most historic, have

withdrawn from the Episcopal Church to align with Anglican bishops in Africa.

•Scandal. Two Colorado pastors, the Rev. Ted Haggard, president of the National

Association of Evangelicals, and the Rev. Paul Barnes, pastor of an evangelical

church in Denver, preached against homosexual behavior and then confessed it.

Haggard resigned in November from his church after his secret life was revealed.

A few weeks later, Barnes admitted sexual infidelity and resigned as well.

•Movie madness. Movies made news with overtly Christian films, but nothing

matched the publicity barrage in May for The Da Vinci Code, based on Dan Brown's

mega-selling book. Churches braced for the film, a thriller in which the heroes

set out to find the descendents of Mary Magdalene, who supposedly fled to France

and gave birth to Jesus' daughter. Debunking books were published by the

crateload, but the movie turned out to be a cultural pop-gun: It came, bored and

confused, and then it went off to DVD.

Faith

brings people together and tears them apart, UT, 28.12.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2006-12-27-faith_x.htm

A Rural Church Loses Its Old Moniker to Atlanta’s

Growing Suburbs

December 25, 2006

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

DACULA, Ga., Dec. 24 — The Rev. Barney Williams has always

been a modernizer. In the 1960s he razed the outhouses at Hog Mountain Baptist

Church and installed indoor plumbing.

That move was controversial, but not nearly as divisive as his more recent big

idea: renaming the 152-year-old country church after a posh new subdivision

nearby, Hamilton Mill (“homes in the 300’s to 700’s,” the sign near the

miniature spinning waterwheel reads).

To Pastor Williams, 81 and in his second stint as the church’s leader, the

decision made perfect sense. The name Hog Mountain, which referred to a

crossroads used by frontiersmen driving their pigs to market in Atlanta, is

disappearing, he says. The school is called Fort Daniel Elementary, the shopping

center is Mountain Crossing. The Hog Mountain Barber Shop recently closed.

And Sunday, the neat white church celebrated its first Christmas Eve as Hamilton

Mill Baptist. “It was good for our mothers,” the members sang in a rendition of

“Old Time Religion,” “and it’s good enough for me.”

On the steps before the service, Jeremy Swancey, 28, said, “This area’s not

known as Hog Mountain anymore.”

Irma Cooper, a 92-year-old who joined the church decades ago, stood nearby in a

bright blue suit. “I’m Hog Mountain,” she said.

Pastor Williams has complained that the name made him the object of ridicule. “A

lot of people in the community resent the word hog; they don’t like it,” he

said. “In reference to the Bible, swine is associated with sin.”

But for many people, Hog Mountain is nothing to be ashamed of. The name change,

approved by a congregational vote, has raised an outcry among old-timers,

current and former church members, and even the Gwinnett County Historical

Society, which sent a chiding letter.

Robin Rundbaken, 36, who moved to the Hamilton Mill subdivision three years ago,

said she had not heard about the hubbub at the church but would prefer that

places kept their historic names. “I’m old-fashioned that way,” she said. “I

would rather they do that than try to appeal to the yuppie prestigious name

thing. And I would think it’s a slap in the face to the members that have grown

up here.”

But Pastor Williams said he had no need to explain replacing such an ungainly

moniker. “The general public knows why we changed the name,” he said. “I don’t

think they’re interested in history.”

Hog Mountain, 40 miles from Atlanta, was never an official town, but the

community began in the early 1800s. There was a fort, a trading post and an inn

called the Hog Mountain House. The church was founded in 1854 by 11 members, led

by Elders David H. Moncrief and Amos Hadaway, according to a historical marker

near the front door. The current building was constructed in 1905.

Gwinnett County has changed drastically since then, especially in recent years,

as farmland has been taken over by the spreading suburbs of Atlanta. Since 1990,

the county has more than doubled in population, and traffic has become extremely

heavy. “Some days it takes 10 minutes to get out of my driveway,” said Claudette

Miller, a church member who opposed the name change.

Ms. Miller said she always thought it was cool to be from a place called Hog

Mountain: “People would say, ‘You must be a hick,’ and I would say, ‘Yep!’ ”

She remembered the church’s recent celebration of its 150th anniversary. The

women dressed in hoop skirts, the men in top hats. The children looked like

little Pilgrims. “I thought we were so proud then,” Ms. Miller said. “What

happened?”

Betty Warbington, a longtime member of the church who left in 1995, about the

time Pastor Williams returned, has written passionate letters and a newspaper

column criticizing the change as a crime against history.

She details how her husband’s father went to the church on wintry Sunday

mornings and lighted the pot-bellied stove before the service. Ms. Warbington’s

uncle was a chorister, and her aunt was the church pianist, a position Ms.

Warbington herself held for more than two decades. She and her husband plan to

be buried in the church’s cemetery.

Ms. Warbington said she suspected that the name was changed in retaliation

against those who blocked Pastor Williams’s plan to sell the church ball field,

next to the oldest part of the cemetery, to a strip mall developer. Pastor

Williams said he intended to use the money to build a gym for younger church

members. “If young people don’t take over the church, it will die,” he said.

Although the congregation voted 3 to 1 in favor of the name change, it was

difficult to find proponents who would explain their reasons. Church members

have tired of publicity and have been asked not to discuss the issue.

But evidently, the name is no more likely to appeal to the young than the old.

Traci Drinkwater, 15, a member, and her friend Elyse Young, 17, a frequent

visitor, said they preferred the name Hog Mountain.

“Everything’s changing to fit the Hamilton Mill folk,” Elyse said. “They’re

snooty. Money’s what it’s all about.”

Traci added: “If they weren’t coming here with the old name, then they wouldn’t

be coming here for the right reasons. It’s not the name, it’s what’s on the

inside.”

A Rural Church

Loses Its Old Moniker to Atlanta’s Growing Suburbs, NYT, 25.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/25/us/25church.html

At Axis of Episcopal Split, an Anti-Gay Nigerian

December 25, 2006

The New York Times

By LYDIA POLGREEN and LAURIE GOODSTEIN

ABUJA, Nigeria, Dec. 20 — The way he tells the story, the

first and only time Archbishop Peter J. Akinola knowingly shook a gay person’s

hand, he sprang backward the moment he realized what he had done.

Archbishop Akinola, the conservative leader of Nigeria’s Anglican Church who has

emerged at the center of a schism over homosexuality in the global Anglican

Communion, re-enacted the scene from behind his desk Tuesday, shaking his head

in wonder and horror.

“This man came up to me after a service, in New York I think, and said, ‘Oh,

good to see you bishop, this is my partner of many years,’ ” he recalled. “I

said, ‘Oh!’ I jumped back.”

Archbishop Akinola, a man whose international reputation has largely been built

on his tough stance against homosexuality, has become the spiritual head of 21

conservative churches in the United States. They opted to leave the Episcopal

Church over its decision to consecrate an openly gay bishop and allow churches

to bless same-sex unions. Among the eight Virginia churches to announce they had

joined the archbishop’s fold last week are The Falls Church and Truro Church,

two large, historic and wealthy parishes.

In a move attacked by some church leaders as a violation of geographical

boundaries, Archbishop Akinola has created an offshoot of his Nigerian church in

North America for the discontented Americans. In doing so, he has made himself

the kingpin of a remarkable alliance between theological conservatives in North

America and the developing world that could tip the power to conservatives in

the Anglican Communion, a 77-million member confederation of national churches

that trace their roots to the Church of England and the Archbishop of

Canterbury.

“He sees himself as the spokesperson for a new Anglicanism, and thus is a direct

challenge to the historic authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury,” said the

Rev. Dr. Ian T. Douglas of the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Mass.

The 62-year-old son of an illiterate widow, Archbishop Akinola now heads not

only Nigeria — the most populous province, or region, in the Anglican Communion,

with at least 17 million members — but also the organizations representing the

leaders of Anglican provinces in Africa and the developing world. He has also

become the most visible advocate for a literal interpretation of Scripture,

challenging the traditional Anglican approach of embracing diverse theological

viewpoints.

“Why didn’t God make a lion to be a man’s companion?” Archbishop Akinola said at

his office here in Abuja. “Why didn’t he make a tree to be a man’s companion? Or

better still, why didn’t he make another man to be man’s companion? So even from

the creation story, you can see that the mind of God, God’s intention, is for

man and woman to be together.”

Archbishop Akinola’s views on homosexuality — that it is an abomination akin to

bestiality and pedophilia — are fairly mainstream here. Nigeria is a deeply

religious country, evenly divided between Christians and Muslims, and attitudes

toward homosexuality, women’s rights and marriage are dictated largely by

scripture and enforced by deep social taboos.

Archbishop Akinola spoke forcefully about his unswerving convictions against

homosexuality, the ordination of women and the rise of what he called “the

liberal agenda,” which he said had “infiltrated our seminaries” in the Anglican

Communion.

This view emanating from the developing world is hardly unique to the Anglican

church. More and more, churches of many denominations in what many Christian

leaders call the “global south,” encompassing Latin America, Africa and parts of

Asia, which share these views, are surging as church attendance lags in

developed countries.

Bishop Martyn Minns, the rector of Truro Church in Fairfax, Va., who was

consecrated by Archbishop Akinola this year to serve as his missionary bishop in

North America, said Archbishop Akinola was motivated by a conviction that the

Anglican Communion must change its colonial-era leadership structure and

mentality.

“He doesn’t want to be the man; he just no longer wants to be the boy,” Bishop

Minns said. “He wants to be treated as an equal leader, with equal respect.”

Even among Anglican conservatives, Archbishop Akinola is not universally

beloved. In November 2005, he published a letter purporting to be from the

leaders, known as primates, of provinces in the global south. It called Europe a

“spiritual desert” and criticized the Church of England. Three of the bishops

who supposedly signed it later denied adding their names. Some bishops in

southern Africa have also challenged his fixation with homosexuality, when AIDS

and poverty are a crisis for the continent.

He has been chastised more recently for creating a missionary branch of the

Nigerian church in the United States, called the Convocation of Anglicans in

North America, despite Anglican rules and traditions prohibiting bishops from

taking control of churches or priests not in their territory.

“There are primates who are very, very concerned about it,” said Archbishop

Drexel Gomez, the primate of the West Indies, because “it introduces more

fragmentation.”

Other conservative American churches that have split from the Episcopal Church,

the American branch of the Anglican Communion, have aligned themselves with

other archbishops, in Rwanda, Uganda and several provinces in Latin America —

often because they already had ties to these provinces through mission work.

Archbishop Gomez said he understood Archbishop Akinola’s actions because the

American conservatives felt an urgent need to leave the Episcopal Church and

were unwilling to wait for a new covenant being written for the Anglican

Communion. The new covenant is a lengthy and uncertain process led by Archbishop

Gomez that some conservatives hope will eventually end the impasse over

homosexuality.

One of Archbishop Akinola’s principal arguments, often heard from other

conservatives as well, is that Christianity in Nigeria, a country where

religious violence has killed tens of thousands in the past decade, must guard

its flank lest Islam overtake it. “The church is in the midst of Islam,” he

said. “Should the church in this country begin to teach that it is appropriate,

that it is right to have same sex unions and all that, the church will simply

die.”

He supports a bill in Nigeria’s legislature that would make homosexual sex and

any public expression of homosexual identity a crime punishable by five years in

prison.

The bill ostensibly aims to ban gay marriage, but it includes measures so

extreme that the State Department warned that they would violate basic human

rights. Strictly interpreted, the bill would ban two gay people from going out

to dinner or seeing a movie together.

It could also lead to the arrest and imprisonment of members of organizations

providing all manner of services, particularly those helping people with AIDS.

“They are very loose, those provisions,” said Dorothy Aken ’Ova of the

International Center for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, a charity that works

with rape victims, AIDS patients and gay rights groups. “It could target just

about anyone, based on any form of perception from anybody.”

Archbishop Akinola said he supported any law that limited marriage to

heterosexuals, but declined to say whether he supported the specific provisions

criminalizing gay associations. “No bishop in this church will go out and say,

‘This man is gay, put him in jail,’ ” the archbishop said. But, he added,

Nigeria has the right to pass such a law if it reflects the country’s values.

“Does Nigeria tell America what laws to make?” he said. “Does Nigeria tell

England what laws to make? This arrogance, this imperial tendency, should stop

for God’s sake.”

Though he insisted that he was not seeking power or influence, he is clearly

relishing the curious role reversal of African archbishops sending missionaries

to a Western society he sees as increasingly godless.

Asked whether his installing a bishop in the United States violated the church’s

longstanding rules, he responded heatedly that he was simply doing what Western

churches had done for centuries, sending a bishop to serve Anglicans where there

is no church to provide one.

Archbishop Akinola argues that the Convocation, his group in the United States,

was established last year to serve Nigerian Anglicans unhappy with the direction

of the Episcopal Church, and eventually began to attract non-Nigerians who

shared their views. Other church officials and experts say Archbishop Akinola’s

intention for the Convocation was to attract Americans and become a rival to the

Episcopal Church.

“Self-seeking, self-glory, that is not me,” he said. “No. Many people say I

embarrass them with my humility.”

Anyone who criticizes him as power-seeking is simply trying to undermine his

message, he said. “The more they demonize, the stronger the works of God,” he

said.

Lydia Polgreen reported from Abuja, and Laurie Goodstein from New York.

At Axis of

Episcopal Split, an Anti-Gay Nigerian, NYT, 25.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/25/world/africa/25episcopal.html?hp&ex=1167109200&en=ed16045828e5ecba&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Pastor at Haggard's New Life Church resigns over 'sexual

misconduct'

Posted 12/19/2006 10:17 AM ET

AP

USA Today

COLORADO SPRINGS (AP) — A pastor who worked with young

adults at New Life Church has admitted sexual misconduct and resigned just weeks

after former church leader Ted Haggard stepped down over sexual immorality.

Christopher Beard, who headed the "twentyfourseven"

ministry that taught leadership skills to young adults, resigned Friday, said

Rob Brendle, an associate pastor at the 14,000-member church.

Brendle said Beard told church officials about "a series of decisions displaying

poor judgment, including one incident of sexual misconduct several years ago."

The church said in a statement that the misconduct was with another unmarried

adult several years ago. Beard, who worked at the church for nine years, has

since married.

Brendle would not elaborate about the nature of the misconduct but said it did

not involve Haggard, who acknowledged he paid a man for a massage and for

methamphetamine but said he did not have sex with the man and did not use the

drug.

Beard's resignation was first reported Monday by The Denver Post and The Gazette

in Colorado Springs. The church said it wouldn't comment further. A residential

phone number listed in Beard's name was disconnected.

The church's outside Board of Overseers was asked to examine the "spiritual

character" of its 200 staff members after Haggard resigned last month from the

church and as president of the National Association of Evangelicals.

"We recognize there will be increased scrutiny of our church in the wake of the

scandal," Brendle said.

He said Beard discussed his "misconduct" during a meeting with the Board of

Overseers, made up of four pastors from other congregations.

Beard was reprimanded by the church in 2002, when police broke up a

twentyfourseven training exercise he led in a church parking lot involving fake

assault rifles.

Haggard and his wife, Gayle Haggard, are undergoing three weeks of counseling at

an undisclosed center in Arizona.

Pastor at

Haggard's New Life Church resigns over 'sexual misconduct', UT, 19.12.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-12-19-newlifechurch_x.htm

Episcopal Parishes in Virginia Vote to Secede

December 18, 2006

The New York Times

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN

Two large and influential Episcopal parishes in Virginia

voted overwhelmingly yesterday to leave the Episcopal Church and to affiliate

with the Anglican archbishop of Nigeria, a conservative leader in a churchwide

fight over homosexuality.

Five smaller churches in Virginia also announced yesterday that they had voted

to secede, joining four others that have already left and three more expected to

announce their decisions soon. Some affiliated with other archbishops in Africa.

The secessions could lead to battles over the churches’ property, although both

sides say they want to avoid legal fights. The move is also likely to escalate

divisions in the worldwide Anglican Communion, a 77-million-member alliance in

which the Episcopal Church is the American branch.

The Rev. Martyn Minns, rector at one of the two large parishes, Truro Church in

Fairfax, said at a news conference: “A burden is being lifted. There are new

possibilities breaking through.”

Clergy members at some of these churches have for many years criticized what

they regard as a leftward drift in the Episcopal Church and saw the consecration

of an openly gay bishop in New Hampshire in 2003 as the last straw.

Episcopal Church leaders tried to persuade them that the church could

accommodate everyone. The conservatives are a minority in a denomination with

7,200 congregations in 100 dioceses in the United States. Since 2003, about 36

other churches have left, according to the Episcopal News Service. Several

dioceses have also taken steps toward separation.

Most of the breakaway churches in Virginia are joining the Convocation of

Anglicans in North America, an offshoot of the Nigerian church led by the

archbishop of Nigeria, Peter J. Akinola.

But there is a dispute over whether other leaders in the communion will

recognize the legitimacy of the convocation. Under Anglican rules and

traditions, bishops are not to take control of churches outside their

geographical boundaries from the recognized presiding bishops.

Father Minns was consecrated by Archbishop Akinola this year as a bishop in the

Nigerian church to lead the convocation in the United States, in the hope that

other disaffected churches would gather under that banner.

Bishop Peter James Lee of the Diocese of Virginia, where the Episcopal Church

has had roots for nearly 400 years, said his diocese had worked to keep the

disaffected churches in the fold.

“The votes today have compromised these discussions and have created Nigerian

congregations occupying Episcopal churches,” Bishop Lee said. “This is not the

future of the Episcopal Church envisioned by our forebears.”

The bishop also said that, under church law, parish property was “held in trust”

for the denomination and the diocese. “As stewards of this historic trust, we

fully intend to assert the church’s canonical and legal rights over these

properties,” he said.

Ninety-two percent of the parishioners who cast ballots at Truro Church, and 90

percent at the Falls Church, which is in Falls Church, voted to pull out.

Sarah R. Bartenstein, a member of the standing committee for the Diocese of

Virginia, said the diocese was concerned about the members of the departing

churches who did not want to leave and had no other Episcopal parish in their

community.

“They have been unfortunately overlooked in all of this,” Ms. Bartenstein said.

Episcopal Parishes

in Virginia Vote to Secede, NYT, 18.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/18/us/18episcopal.html

Episcopalians Are Reaching Point of Revolt

December 17, 2006

The New York Times

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN

For about 30 years, the Episcopal Church has been one big

unhappy family. Under one roof there were female bishops and male bishops who

would not ordain women. There were parishes that celebrated gay weddings and

parishes that denounced them; theologians sure that Jesus was the only route to

salvation, and theologians who disagreed.

Now, after years of threats, the family is breaking up.

As many as eight conservative Episcopal churches in Virginia are expected to

announce today that their parishioners have voted to cut their ties with the

Episcopal Church. Two are large, historic congregations that minister to the

Washington elite and occupy real estate worth a combined $27 million, which

could result in a legal battle over who keeps the property.

In a twist, these wealthy American congregations are essentially putting

themselves up for adoption by Anglican archbishops in poorer dioceses in Africa,

Asia and Latin America who share conservative theological views about

homosexuality and the interpretation of Scripture with the breakaway Americans.

“The Episcopalian ship is in trouble,” said the Rev. John Yates, rector of The

Falls Church, one of the two large Virginia congregations, where George

Washington served on the vestry. “So we’re climbing over the rails down to

various little lifeboats. There’s a lifeboat from Bolivia, one from Rwanda,

another from Nigeria. Their desire is to help us build a new ship in North

America, and design it and get it sailing.”

Together, these Americans and their overseas allies say they intend to form a

new American branch that would rival or even supplant the Episcopal Church in

the worldwide Anglican Communion, a confederation of national churches that

trace their roots to the Church of England and the archbishop of Canterbury.

The archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev. Rowan Williams, is now struggling to

hold the communion together while facing a revolt on many fronts from emboldened

conservatives. Last week, conservative priests in the Church of England warned

him that they would depart if he did not allow them to sidestep liberal bishops

and report instead to sympathetic conservatives.

In Virginia, the two large churches are voting on whether they want to report to

the powerful archbishop of Nigeria, Peter Akinola, an outspoken opponent of

homosexuality who supports legislation in his country that would make it illegal

for gay men and lesbians to form organizations, read gay literature or eat

together in a restaurant. Archbishop Akinola presides over the largest province

in the 77-million-member Anglican Communion; it has more than 17 million

members, dwarfing the Episcopal Church, with 2.3 million.

If all eight Virginia churches vote to separate, the Diocese of Virginia, the

largest Episcopal diocese in the country, will lose about 10 percent of its

90,000 members. In addition, four churches in Virginia have already voted to

secede, and two more are expected to vote soon, said Patrick N. Getlein,

secretary of the diocese.

Two weeks ago, the entire diocese in San Joaquin, Calif., voted to sever its

ties with the Episcopal Church, a decision it would have to confirm in a second

vote next year. Six or more American dioceses say they are considering such a

move.

In the last three years, since the Episcopal Church consecrated V. Gene

Robinson, a gay man who lives with his partner, as bishop of New Hampshire,

about three dozen American churches have voted to secede and affiliate with

provinces overseas, according to The Episcopal News Service.

However, the secession effort in Virginia is being closely watched by Anglicans

around the world because so many churches are poised to depart simultaneously.

Virginia has become a central stage, both for those pushing for secession and

for those trying to prevent it.

The Diocese of Virginia is led by Bishop Peter James Lee, the longest-serving

Episcopal bishop and a centrist who, both sides agree, has been gracious to the

disaffected churches and worked to keep them in the fold.

Bishop Lee has made concessions other bishops would not. He has allowed the

churches to keep their seats in diocesan councils, even though they stopped

contributing to the diocesan budget in protest. When some of the churches

refused to have Bishop Lee perform confirmations in their parishes, he flew in

the former archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev. George Carey, a conservative

evangelical, to take his place.

“Our Anglican tradition has always been a very large tent in which people with

different theological emphases can live together,” Bishop Lee said in a

telephone interview. “I’m very sorry some in these churches feel that this is no

longer the case for them. It certainly is their choice and their decision. No

one is forcing them to do this.”

The Diocese of Virginia is also home to the Rev. Martyn Minns, a main organizer

in the global effort by conservative Anglicans to ostracize the Episcopal

Church. Mr. Minns is the priest in charge of Truro Church, the second of the two

historic Virginia parishes now voting on secession.

Anglican rules and traditions prohibit bishops from crossing geographical

boundaries to take control of churches or priests not in their territory. So

Archbishop Akinola and his American allies have tried to bypass that by

establishing a branch of the Nigerian church in the United States, the

Convocation of Anglicans in North America. Archbishop Akinola has appointed Mr.

Minns as his key “missionary bishop” to spread the gospel to Americans on his

behalf.

Mr. Minns and other advocates of secession have suggested to the voters that the

convocation arrangement has the blessing of the Anglican hierarchy. But on

Friday, the Anglican Communion office in London issued a terse statement saying

the convocation had not been granted “any official status within the communion’s

structures, nor has the archbishop of Canterbury indicated any support for its

establishment.”

The voting in Virginia, however, was already well under way, with ballot boxes

open for a week starting last Sunday. Church leaders say they need 70 percent of

the voters to approve the secession for it to take effect.

If the vote is to secede, the churches and the diocese will fight to keep

ownership of Truro Church, in Fairfax, and The Falls Church, in Falls Church,

Va., a city named for the church.

Henry D. W. Burt, a member of the standing committee of the Virginia Diocese,

grew up in The Falls Church and recently urged members not to secede. He said in

an interview: “We’re not talking about Class A office space in Arlington, Va.

We’re talking about sacred ground.”

Neither side says it wants to go to court over control of the church property,

but both say the law is on their side.

At one of the four Virginia parishes that has already voted to secede, All

Saints Church in Dale City, the tally was 402 to 6. But that church had already

negotiated a settlement to rent its property from the diocese for $1 each year

until it builds another church.

The presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, Katharine Jefferts Schori, said in

an e-mail response to a request for an interview that such splits reflect a

polarized society, as well as the “anxiety” and “discomfort” that many people

feel when they are asked to live with diversity.

“The quick fix embraced in drawing lines or in departing is not going to be an

ultimate solution for our discomfort,” she said.

Soon, Bishop Jefferts Schori herself will become the issue. Archbishop Akinola

and some other leaders of provinces in developing countries have said they will

boycott their primates’ meeting in Tanzania in February unless the archbishop of

Canterbury sends a second representative for the American conservatives.

“It’s a huge amount of mess,” said the Rev. Dr. Kendall Harmon, canon theologian

of the Diocese of South Carolina, who is aligned with the conservatives. “As

these two sides fight, a lot of people in the middle of the Episcopal Church are

exhausted and trying to hide, and you can’t. When you’re in a family and the two

sides are fighting, it affects everybody.”

Episcopalians Are

Reaching Point of Revolt, NYT, 17.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/17/us/17episcopal.html?hp&ex=1166418000&en=0849e2dc5db0755e&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Second Colorado evangelical resigns over gay sex

Tue Dec 12, 2006 9:00pm ET

Reuters

DENVER (Reuters) - A second Colorado evangelical leader in

little over a month has resigned from the pulpit over a scandal involving gay

sex, church officials said on Tuesday.

Paul Barnes has resigned from the 2,100-member Grace Chapel, a church he founded

in suburban Denver, said church spokeswoman Michelle Ames.

Barnes' resignation follows last month's admission by high-profile preacher Ted

Haggard that he was guilty of unspecified "sexual immorality" after a male

prostitute went public with their liaisons.

Many evangelical Christians view homosexuality as a sin, though some are more

strident on the issue than others.

Ames said Barnes told his congregation in a videotaped

message on Sunday he had "struggled with homosexuality since he was five years

old."

Barnes was confronted by an associate pastor of the church who received an

anonymous phone call from a person who heard someone was threatening to go

public with the names of Barnes and other evangelical leaders who engaged in

homosexual behavior, Ames said.

Barnes, who is married with two grown daughters, then confessed to church

elders.

Haggard had been a vocal opponent of gay marriage. He stepped down as president

of the National Association of Evangelicals and as pastor of the 14,000-member

New Life "mega-church" in Colorado Springs.

Second Colorado

evangelical resigns over gay sex, R, 12.12.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=domesticNews&storyID=2006-12-13T015957Z_01_N12378716_RTRUKOC_0_US-EVANGELICAL-SCANDAL-GAY.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C5-domesticNews-2

Gay and Evangelical, Seeking Paths of Acceptance

December 12, 2006

The New York Times

By NEELA BANERJEE

RALEIGH, N.C. — Justin Lee believes that the Virgin birth

was real, that there is a heaven and a hell, that salvation comes through Christ

alone and that he, the 29-year-old son of Southern Baptists, is an evangelical

Christian.

Just as he is certain about the tenets of his faith, Mr. Lee also knows he is

gay, that he did not choose it and cannot change it.

To many people, Mr. Lee is a walking contradiction, and most evangelicals and

gay people alike consider Christians like him horribly deluded about their

faith. “I’ve gotten hate mail from both sides,” said Mr. Lee, who runs

gaychristian.net, a Web site with 4,700 registered users that mostly attracts

gay evangelicals.

The difficulty some evangelicals have in coping with same-sex attraction was

thrown into relief on Sunday when the pastor of a Denver megachurch, the Rev.

Paul Barnes, resigned after confessing to having sex with men. Mr. Barnes said

he had often cried himself to sleep, begging God to end his attraction to men.

His departure followed by only a few weeks that of the Rev. Ted Haggard, then

the president of the National Association of Evangelicals and the pastor of a

Colorado Springs megachurch, after a male prostitute said Mr. Haggard had had a

relationship with him for three years.

Though he did not publicly admit to the relationship, in a letter to his

congregation, Mr. Haggard said that he was “guilty of sexual immorality” and

that he had struggled all his life with impulses he called “repulsive and dark.”

While debates over homosexuality have upset many Christian and Jewish

congregations, gay evangelicals come from a tradition whose leaders have led the

fight against greater acceptance of homosexuals.

Gay evangelicals seem to have few paths carved out for them: they can leave

religion behind; they can turn to theologically liberal congregations that often

differ from the tradition they grew up in; or they can enter programs to try to

change their behavior, even their orientation, through prayer and support.

But as gay men and lesbians grapple with their sexuality and an evangelical

upbringing they cherish, some have come to accept both. And like other

Christians who are trying to broaden the definition of evangelical to include

other, though less charged, concerns like the environment and AIDS, gay

evangelicals are trying to expand the understanding of evangelical to include

them, too.

“A lot of people are freaked out because their only exposure to evangelicalism

was a bad one, and a lot ask, ‘Why would you want to be part of a group that

doesn’t like you very much?’ ” Mr. Lee said. “But it’s not about membership in

groups. It’s about what I believe. Just because some people who believe the same

things I do aren’t very loving doesn’t mean I stop believing what I do.”

The most well-known gay evangelical may be the Rev. Mel White, a former seminary

professor and ghostwriter for the Rev. Jerry Falwell. Mr. White, who came out

publicly in 1993, helped found Soulforce, a group that challenges Christian

denominations and other institutions regarding their stance on homosexuality.

But over the last 30 years, rather than push for change, gay evangelicals have

mostly created organizations where they are accepted.

Members of Evangelicals Concerned, founded in 1975 by a therapist from New York,

Ralph Blair, worship in cities including Denver, New York and Seattle. Web sites

have emerged, like Christianlesbians.com and Mr. Lee’s gaychristian.net, whose

members include gay people struggling with coming out, those who lead celibate

lives and those in relationships.

Justin Cannon, 22, a seminarian who grew up in a conservative Episcopal parish

in Michigan, started two Web sites, including an Internet dating site for gay

Christians.

“About 90 percent of the profiles say ‘Looking for someone with whom I can share

my faith and that it would be a central part of our relationship,’ ” Mr. Cannon

said, “so not just a life partner but someone with whom they can connect

spiritually.”

But for most evangelicals, gay men and lesbians cannot truly be considered

Christian, let alone evangelical.

“If by gay evangelical is meant someone who claims both to abide by the

authority of Scripture and to engage in a self-affirming manner in homosexual

unions, then the concept gay evangelical is a contradiction,” Robert A. J.

Gagnon, associate professor of New Testament at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary,

said in an e-mail message.

“Scripture clearly, pervasively, strongly, absolutely and counterculturally

opposes all homosexual practice,” Dr. Gagnon said. “I trust that gay

evangelicals would argue otherwise, but Christian proponents of homosexual

practice have not made their case from Scripture.”

In fact, both sides look to Scripture. The debate is largely over seven passages

in the Bible about same-sex couplings. Mr. Gagnon and other traditionalists say

those passages unequivocally condemn same-sex couplings.

Those who advocate acceptance of gay people assert that the passages have to do

with acts in the context of idolatry, prostitution or violence. The Bible, they

argue, says nothing about homosexuality as it is largely understood today as an

enduring orientation, or about committed long-term, same-sex relationships.

For some gay evangelicals, their faith in God helped them override the biblical

restrictions people preached to them. One lesbian who attends Pullen Memorial

Baptist Church in Raleigh said she grew up in a devout Southern Baptist family

and still has what she calls the “faith of a child.” When she figured out at 13

that she was gay, she believed there must have been something wrong with the

Bible for condemning her.

“I always knew my own heart: that I loved the Lord, I loved Jesus, loved the

church and felt the Spirit move through me when we sang,” said the woman, who

declined to be identified to protect her partner’s privacy. “I felt that if God

created me, how is that wrong?”

But most evangelicals struggle profoundly with reconciling their faith and

homosexuality, and they write to people like Mr. Lee.

There is the 65-year-old minister who is a married father and gay. There are the

teenagers considering suicide because they have been taught that gay people are

an abomination. There are those who have tried the evangelical “ex-gay”

therapies and never became straight.

Mr. Lee said he and his family, who live in Raleigh, have been through almost

all of it. His faith was central to his life from an early age, he said. He got

the nickname Godboy in high school. But because of his attraction to other boys,

he wept at night and begged God to change him. He was certain God would, but

when that did not happen, he said, it called everything into question.

He knew no one who was gay who could help, and he could not turn to his church.

So for a year, Mr. Lee went to the library almost every day with a notebook and

the bright blue leather-bound Bible his parents had given him. He set up his Web

site to tell his friends what he was learning through his readings, but e-mail

rolled in from strangers, because, he says, other gay evangelicals came to

understand they were not alone.

“I told them I don’t have the answers,” Mr. Lee said, “but we can pray together

and see where God takes us.”

But even when they accept themselves, gay evangelicals often have difficulty

finding a community. They are too Christian for many gay people, with the

evangelical rock they listen to and their talk of loving God. Mr. Lee plans to

remain sexually abstinent until he is in a long-term, religiously blessed

relationship, which would make him a curiosity in straight and gay circles

alike.

Gay evangelicals seldom find churches that fit. Congregations and denominations

that are open to gay people are often too liberal theologically for

evangelicals. Yet those congregations whose preaching is familiar do not welcome

gay members, those evangelicals said.

Clyde Zuber, 49, and Martin Fowler, 55, remember sitting on the curb outside

Lakeview Baptist Church in Grand Prairie, Tex., almost 20 years ago, Sunday

after Sunday, reading the Bible together, after the pastor told them they were

not welcome inside. The men met at a Dallas church and have been together 23

years. In Durham, N.C., they attend an Episcopal church and hold a Bible study

for gay evangelicals every Friday night at their home.

“Our faith is the basis of our lives,” said Mr. Fowler, a soft-spoken professor

of philosophy. “It means that Jesus is the Lord of our household, that we

resolve differences peacefully and through love.”

Their lives seem a testament to all that is changing and all that holds fast

among evangelicals. Their parents came to their commitment ceremony 20 years

ago, their decision ultimately an act of loyalty to their sons, Mr. Zuber said.

But Mr. Zuber’s sister and brother-in-law in Virginia remain convinced that the

couple is sinning. “They’re worried we’re going to hell,” Mr. Zuber said. “They

say, ‘We love you, but we’re concerned.’ ”

Gay and

Evangelical, Seeking Paths of Acceptance, NYT, 12.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/12/us/12evangelical.html

Settlement Set in Oregon Priest Abuse Case

December 11, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 2:15 p.m. ET

The New York Times

EUGENE, Ore. (AP) -- About 150 people claiming they were

sexually abused by priests have agreed to settle their lawsuits against the

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Portland, a federal judge announced Monday.

U.S. District Judge Michael Hogan declined to release the dollar amount, but he

said all current and future claims could be covered by the archdiocese without

selling off property held by parishes and schools.

All parties involved with the case have been under a strict gag order not to

discuss it publicly.

The Archdiocese of Portland was the first in the nation to seek bankruptcy

protection to head off a massive lawsuit claiming sexual abuse by priests. It

had faced a $135 million lawsuit alleging sexual abuse by the late Rev. Maurice

Grammond, a priest at the center of a number of Oregon abuse claims.

Three other dioceses -- Tucson, Ariz.; Spokane, Wash.; and Davenport, Iowa --

have also sought bankruptcy protection from a flood of lawsuits by people

alleging sexual abuse by priests. Tucson emerged from the process in 2005.

Earlier this month, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles said it would pay $60 million

to settle 45 abuse lawsuits, possibly selling off some of its property in

Southern California to help cover the cost.

Roman Catholic dioceses in the United States have paid an estimated $1.5 billion

since 1950 to handle claims of sex abuse by its priests.

------

On the Net:

Archdiocese of Portland: http://www.archpdx.org

Settlement Set in

Oregon Priest Abuse Case, NYT, 11.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Church-Abuse-Settlement.html?hp&ex=1165899600&en=85c9988fff6c1512&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Religion for a Captive Audience, Paid For by Taxes

December 10, 2006

The New York Times

By DIANA B. HENRIQUES and ANDREW LEHREN

Life was different in Unit E at the state prison outside

Newton, Iowa.

The toilets and sinks — white porcelain ones, like at home — were in a separate

bathroom with partitions for privacy. In many Iowa prisons, metal

toilet-and-sink combinations squat beside the bunks, to be used without privacy,

a few feet from cellmates.

The cells in Unit E had real wooden doors and doorknobs, with locks. More books

and computers were available, and inmates were kept busy with classes, chores,

music practice and discussions. There were occasional movies and events with

live bands and real-world food, like pizza or sandwiches from Subway. Best of

all, there were opportunities to see loved ones in an environment quieter and

more intimate than the typical visiting rooms.

But the only way an inmate could qualify for this kinder mutation of prison life

was to enter an intensely religious rehabilitation program and satisfy the

evangelical Christians running it that he was making acceptable spiritual

progress. The program — which grew from a project started in 1997 at a Texas

prison with the support of George W. Bush, who was governor at the time — says

on its Web site that it seeks “to ‘cure’ prisoners by identifying sin as the

root of their problems” and showing inmates “how God can heal them permanently,

if they turn from their sinful past.”

One Roman Catholic inmate, Michael A. Bauer, left the program after a year,

mostly because he felt the program staff and volunteers were hostile toward his

faith.

“My No. 1 reason for leaving the program was that I personally felt spiritually

crushed,” he testified at a court hearing last year. “I just didn’t feel good

about where I was and what was going on.”

For Robert W. Pratt, chief judge of the federal courts in the Southern District

of Iowa, this all added up to an unconstitutional use of taxpayer money for

religious indoctrination, as he ruled in June in a lawsuit challenging the

arrangement.

The Iowa prison program is not unique. Since 2000, courts have cited more than a

dozen programs for having unconstitutionally used taxpayer money to pay for

religious activities or evangelism aimed at prisoners, recovering addicts, job

seekers, teenagers and children.

Nevertheless, the programs are proliferating. For example, the Corrections

Corporation of America, the nation’s largest prison management company, with 65

facilities and 71,000 inmates under its control, is substantially expanding its

religion-based curriculum and now has 22 institutions offering residential

programs similar to the one in Iowa. And the federal Bureau of Prisons, which

runs at least five multifaith programs at its facilities, is preparing to seek

bids for a single-faith prison program as well.

Government agencies have been repeatedly cited by judges and government auditors

for not doing enough to guard against taxpayer-financed evangelism. But some

constitutional lawyers say new federal rules may bar the government from

imposing any special requirements for how faith-based programs are audited.

And, typically, the only penalty imposed when constitutional violations are

detected is the cancellation of future financing — with no requirement that

money improperly used for religious purposes be repaid.

But in a move that some constitutional lawyers found surprising, Judge Pratt

ordered the prison ministry in the Iowa case to repay more than $1.5 million in

government money, saying the constitutional violations were serious and clearly

foreseeable.

His decision has been appealed by the prison ministry to a federal appeals court

and fiercely protested by the attorneys general of nine states and lawyers for a

number of groups advocating greater government accommodation of religious

groups. The ministry’s allies in court include the Bush administration, which

argued that the repayment order could derail its efforts to draw more religious

groups into taxpayer-financed programs.

Officials of the Iowa program said that any anti-Catholic comments made to

inmates did not reflect the program’s philosophy, and are not condoned by its

leadership.

Jay Hein, director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community

Initiatives, said the Iowa decision was unfair to the ministry and reflects an

“overreaching” at odds with legal developments that increasingly “show favor to

religion in the public square.”

And while he acknowledged the need for vigilance, he said he did not think the

constitutional risks outweighed the benefits of inviting “faith-infused”

ministries, like the one in Iowa, to provide government-financed services to

“people of faith who seek to be served in this ‘full-person’ concept.”

Crossing a Bright Line

Over the last two decades, legislatures, government agencies and the courts have

provided religious organizations with a widening range of regulatory and tax

exemptions. And in the last decade religious institutions have also been granted

access to public money once denied on constitutional grounds, including historic

preservation grants and emergency reconstruction funds.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that public money could be used for religious

instruction or indoctrination, but only when the intended beneficiaries made the

choice themselves between religious and secular programs — as when parents

decide whether to use tuition vouchers at religious schools or secular ones. The

court emphasized the difference between such “indirect” financing, in which the

money flows through beneficiaries who choose that program, and “direct” funding,

where the government chooses the programs that receive money.

But even in today’s more accommodating environment, constitutional scholars

agree that one line between church and state has remained fairly bright: The

government cannot directly finance or support religious evangelism or

indoctrination. That restriction typically has not loomed large when public

money goes to religious charities providing essentially secular services, like

job training, after-school tutoring, child care or food banks. In such cases,

the beneficiaries need not accept the charity’s religious beliefs to get the

secular benefits the government is financing.

The courts have taken a different view, however, when public money goes directly

to groups, like the Iowa ministry, whose method of helping others is to

introduce them to a specific set of religious beliefs — and whose success

depends on the beneficiary accepting those core beliefs. In those cases, most of

the challenged grants have been struck down as unconstitutional.

Those who see faith-based groups as exceptionally effective allies in the battle

against criminal recidivism, teen pregnancy, addiction and other social ills say

these cases are rare, compared with the number of programs receiving funds, and

should not tarnish the concept of bringing more religious groups into publicly

financed programs, so long as any direct financing is used only for secular

expenses.

That concept has been embodied most prominently since 2001 in the Bush

administration’s Faith-Based and Community Initiative, a high-profile effort to

encourage religious and community groups to participate in government programs.

More than 100 cities and 33 states have established similar initiatives,

according to Mr. Hein.

The basic architecture of these initiatives has so far withstood constitutional

challenge, although the Supreme Court agreed on Dec. 1 to consider a case on

whether taxpayers have legal standing to bring such challenges against the Bush

administration’s program.

Defenders of these initiatives say they are necessary to eliminate longstanding

government policies that discriminated against religious groups — to provide a

level playing field, as one White House study put it.

But critics say the “level playing field” argument ignores the fact that giving

public money directly to ministries that aim at religious conversion poses

constitutional problems that simply do not arise when the money goes elsewhere.

Converting Young People

Those constitutional problems sharpen when young people are the intended

beneficiaries of these transformational ministries. In recent years, several

judges have concluded that children and teenagers, like prisoners, have too few

options and too little power to make the voluntary choices the Supreme Court

requires when public money flows to programs involving religious instruction or

indoctrination.

That was the conclusion last year of a federal judge in Michigan, in a case

filed by Teen Ranch, a nonprofit Christian facility that provides residential

care for troubled or abused children ages 11 to 17.

In 2003, state officials imposed a moratorium on placements of children there,

primarily because of its intensively religious programming. Lawyers for the

ranch went to court to challenge that moratorium.

“Teen Ranch acknowledges that it is overtly and unapologetically a Christian

facility with a Christian worldview that hopes to touch and improve the lives of

the youth served by encouraging their conversion to faith in Christ, or

assisting them in deepening their pre-existing Christian faith,” observed a

United States District judge, Robert Holmes Bell, in a decision released in

September 2005.

Although youngsters in state custody could not choose where to be placed, they

could refuse to go to the ranch if they objected to its religious character. As

a result, the ranch’s lawyers argued, the state money was constitutionally

permissible.

The state contended that the children in its care were “too young, vulnerable

and traumatized” to make genuine choices. The ranch disputed that and added that

the children had case workers and other adults to guide them. Judge Bell

rejected Teen Ranch’s arguments. “Regardless of whether state wards are

particularly vulnerable, they are children,” he wrote.

The ranch in Michigan has discontinued operations pending the outcome of its

appeal, said Mitchell E. Koster, who was its chief operating officer. “We are

confident that our argument will win,” Mr. Koster said. “It’s just a question of

at what level.”

In another case early last year, a federal judge struck down a federal grant in

2003 to MentorKids USA, a ministry based in Phoenix, to provide mentors for the

children of prisoners. In a case filed by the Freedom From Religion Foundation

in Madison, Wis., the judge noted that the exclusively Christian mentors had to

regularly assess whether the young people in their care seemed “to be

progressing in relationship with God.” In a program newsletter offered as

evidence, its director said, “Our goal is to see every young adult choose

Christ.”

The federal government had been clearly informed in advance of the nature of the

MentorKids ministry, said John Gibson, chairman of the group’s board. “The

court’s decision meant that there were 50 kids we could have served that we were

not able to serve.”

In another case, more than $1 million in federal funds went to the Alaska

Christian College in Soldotna, Alaska, which says it provides “a theologically

based post-secondary education” to teenage Native Americans from isolated

villages. But an investigator from the Education Department who visited the

school last year found a first-year curriculum “that is almost entirely

religious in nature.”

The Freedom From Religion Foundation sued to block the financing. The school

promised to use government money only for secular expenses, and federal

financing resumed last May, according to Derek Gaubatz, of the Becket Fund for

Religious Liberty, which represents the college.

A number of government grants to finance sexual abstinence education have been

successfully challenged. For example, the Louisiana Governor’s Program on

Abstinence gave federal money to several religious groups that used it for

clearly unconstitutional purposes, a federal judge ruled in 2002, in a case

filed by the American Civil Liberties Union.

One grant went to a theater company that toured high schools performing a skit

called “Just Say Whoa.” The script contained many religious references including

one in which a character called Bible Guy tells teenagers in the cast: “As

Christians, our bodies belong to the Lord, not to us.”

The federal judge said the grants were so poorly monitored that the state missed

other clear signs of unconstitutional activity — as when one Catholic diocese

sent monthly reports showing that it had used federal money “to support prayer

at abortion clinics, pro-life marches and pro-life rallies.” Gail Dignam,

director of the abstinence program, said that state contracts now emphasize more

clearly that no grant money may be used for religious activities.

The Programs in Prisons

Programs like the one at the Iowa prison are a rare ray of hope for American

prisoners, and governments should encourage them, their supporters say.

“We have 2.3 million Americans in prison today; 700,000 of them will get out of

prison this coming year,” said Mark L. Earley, a former attorney general of

Virginia. Many inmates come out of prison “much more antisocial than when they

came in,” he added. He said he saw faith-based groups as essential partners in

any effective rehabilitation efforts.

Mr. Earley is the president and chief executive of Prison Fellowship Ministries,

based in Lansdowne, Va. With almost $56 million a year in revenue, the ministry

oversees the InnerChange Freedom Initiative, which operates the Iowa program.

Since its birth in 1976, Prison Fellowship has been most closely associated with

one of its founders, Charles W. Colson, who said in a 2002 newsletter that the

InnerChange program demonstrates “that Christ changes lives, and that changing

prisoners from the inside out is the only crime-prevention program that really

works.”

In early 2003, Americans United for Separation of Church and State joined with a

group of Iowa taxpayers and inmates to challenge the InnerChange program in

federal court.

In ruling on that case, Judge Pratt noted that the born-again Christian staff

was the sole judge of an inmate’s spiritual transformation. If an inmate did not

join in the religious activities that were part of his “treatment,” the staff

could write up disciplinary reports, generating demerits the inmate’s parole

board might see. Or they could expel the inmate.

And while the program was supposedly open to all, in practice its content was “a

substantial disincentive” for inmates of other faiths to join, the judge noted.

Although the ministry itself does not condone hostility toward Catholics, Roman

Catholic inmates heard their faith criticized by staff members and volunteers

from local evangelical churches, the judge found. And Jews and Muslims in the

program would have been required to participate in Christian worship services

even if that deeply offended their own religious beliefs.

Mr. Earley said Judge Pratt’s decision was sharply inconsistent with current law

and his standard for separating secular from religious expenses was so extreme

that it would disqualify almost any faith-based program. He acknowledged that

inmates, whatever their own faith, are required to participate in all program

activities, including worship, but he insisted that a religious conversion is

not required for success. InnerChange uses biblical references only to

illustrate a set of universal values, such as integrity and responsibility, and

not to exclude those of other faiths, he said, adding that it was “unfortunate”

if any inmates felt the program denigrated Catholicism or any other Christian

faith. Corrections officials in Iowa declined to comment on the case.

Not all programs in prisons are so narrowly focused. Florida now has three

prisons that offer inmates, who must ask to be housed there, more than two dozen

offerings ranging from various Christian denominations to Orthodox Judaism to

Scientology. But at Newton, Judge Pratt found, there were few options — and no

equivalent programs — without religious indoctrination.

“The state has literally established an Evangelical Christian congregation

within the walls of one of its penal institutions, giving the leaders of that

congregation, i.e., InnerChange employees, authority to control the spiritual,

emotional and physical lives of hundreds of Iowa inmates,” Judge Pratt wrote.

“There are no adequate safeguards present, nor could there be, to ensure that

state funds are not being directly spent to indoctrinate Iowa inmates.”

InnerChange, which has been widely praised by corrections officials and

politicians, operates similar programs at prisons in Texas, Minnesota, Kansas,

Arkansas and, by next spring, Missouri. Officials in those states are monitoring

the Iowa case, but several said they believed their programs were sufficiently

different to survive a similar challenge.

A government-financed religious education program at a county jail in Fort Worth

was struck down by the Texas Supreme Court more than five years ago, and more

lawsuits are pending. Corrections Corporation was among those sued last year by

the Freedom From Religion Foundation, which is challenging a Christian

residential program at a women’s prison in Grant, N.M. The foundation has also

sued the federal Bureau of Prisons over its faith-based rehabilitation programs.

And Americans United, the Iowa plaintiff, and the American Civil Liberties Union

have sued a job-training program run by a religious group at the Bradford County

Jail near Troy, Pa.

Prison Fellowship Ministries is one of about a half-dozen Christian groups that

operate programs at jails and prisons run by the Corrections Corporation. The

company’s lawyers are studying the Iowa decision, said a spokeswoman, Louise

Grant. “But we are not, at this time, changing or altering any of our

programming based on that, or any other ruling.”

Inadequate Monitoring

Government agencies have been criticized repeatedly for inadequately watching

these programs. Besides the criticism in various court decisions, the Government

Accountability Office has twice raised questions about cloudy guidelines and

inadequate safeguards against government-financed evangelism.

In its most recent audit released in June, the G.A.O., which examined

faith-based organizations in four states, found that some were violating federal

rules against proselytizing and that government agencies did not have adequate

safeguards against such violations.

The problem is not that none of these programs are audited. Every group that

gets a federal grant worth more than $500,000 has to pay a private auditor to

examine its books and report to the government. Many federal programs, like

those that provide Medicaid services or help the government allocate arts

grants, require additional audits.

But no supplemental audits are required under the faith-based initiative —

indeed, it would probably violate the Bush administration’s new regulations to

do so, said Robert W. Tuttle, a professor of law and religion at George

Washington University and co-director of legal research, along with Ira C. Lupu,

for the Roundtable on Religion and Social Welfare Policy, a project of the

Rockefeller Institute.

“The rules can be read to prohibit special audit requirements because that would

be considered a stigma, which would be discriminatory,” Professor Tuttle said.

“But that flies in the face of constitutional logic, because religion is

special, and that special quality has to be reflected in program guidelines and

audit rules.”

The G.A.O. also says the government cannot easily or accurately track either how

much money is flowing to groups or whether they are using the funds in

unconstitutional ways.

The Bush administration is already studying whether these constitutional

problems can be resolved by reshaping many government grants into voucher

programs under which the beneficiary decides where the money goes. But vouchers

are a limited solution because most social service agencies need to know that a

certain amount of money is assured before they can begin operations.

Mr. Hein, the White House official, agreed that vouchers could clarify the legal

landscape. But even where they are not practical, he said, the Bush

administration remains committed to keeping the doors to government financing

open for as many religious groups as possible.

Donna Anderson contributed research.

Religion for a

Captive Audience, Paid For by Taxes, NYT, 10.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/10/business/10faith.html?hp&ex=1165813200&en=9d0e1451cc709fc2&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Conservative Jews Allow Gay Rabbis and Unions

December 7, 2006

The New York Times

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN

The highest legal body in Conservative Judaism, the

centrist movement in worldwide Jewry, voted yesterday to allow the ordination of

gay rabbis and the celebration of same-sex commitment ceremonies.

The decision, which followed years of debate, was denounced by traditionalists

in the movement as an indication that Conservative Judaism had abandoned its

commitment to adhere to Jewish law, but celebrated by others as a long-awaited

move toward full equality for gay people.

“We see this as a giant step forward,” said Sarah Freidson, a rabbinical student

and co-chairwoman of Keshet, a student group at the Jewish Theological Seminary

in New York that has been pushing for change.

But in a reflection of the divisions in the movement, the 25 rabbis on the law

committee passed three conflicting legal opinions — one in favor of gay rabbis

and unions, and two against.

In doing so, the committee left it up to individual synagogues to decide whether

to accept or reject gay rabbis and commitment ceremonies, saying that either

course is justified according to Jewish law.

“We believe in pluralism,” said Rabbi Kassel Abelson, chairman of the panel, the

Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly, at a news

conference after the meeting at the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York. “We

recognized from the very beginnings of the movement that no single position

could speak for all members” on the law committee or in the Conservative

movement.

In protest, four conservative rabbis resigned from the law committee, saying

that the decision to allow gay ordination violated Jewish law, or halacha. Among

them were the authors of the two legal opinions the committee adopted that

opposed gay rabbis and same-sex unions.

One rabbi, Joel Roth, said he resigned because the measure allowing gay rabbis

and unions was “outside the pale of halachic reasoning.”

With many Protestant denominations divided over homosexuality in recent years,

the decision by Conservative Judaism’s leading committee of legal scholars will

be read closely by many outside the movement because Conservative Jews say they

uphold Jewish law and tradition, which includes biblical injunctions against

homosexuality.

The decision is also significant because Conservative Judaism is considered the

centrist movement in Judaism, wedged between the liberal Reform and

Reconstructionist movements, which have accepted an openly gay clergy for more

than 10 years, and the more traditional Orthodox, which rejects it.

The move could create confusion in congregations that are divided over the

issue, said Rabbi Jerome Epstein, executive director of the United Synagogue of

Conservative Judaism, which represents the movement’s more than 750 synagogues

with 1.5 million members in North America.

“Most of our congregations will not be of one mind, the same way that we were

not of one mind,” said Rabbi Epstein, also a law committee member. “Our mandate

is to help congregations deal with this pluralism.”

Some synagogues and rabbis could leave the Conservative movement, but many

rabbis and experts cautioned that the law committee’s decision was unlikely to

cause a widespread schism.

Before the vote, some rabbis in Canada, where many Conservative synagogues lean

closer to Orthodoxy than in the United States, threatened to break with the

movement.

But Jonathan D. Sarna, a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis

University, said: “I find it hard to buy the idea that this change, which has

been widely expected, will lead anybody to leave, because synagogues that don’t

want to make changes will simply point to the rulings that will allow them not

to make any changes. This is not like a papal edict.”

The question of whether to admit and ordain openly gay rabbinic students will

now be taken up by the movement’s seminaries. The University of Judaism, in Los

Angeles, has already signaled its support, said Rabbi Elliot Dorff, its rector

and the vice chairman of the law committee. He co-wrote the legal opinion

allowing gay ordination and unions that passed on Wednesday.

The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, the flagship school in Conservative

Judaism, will take up the issue in meetings of the faculty, the students and the

trustees in the next few months, Chancellor-elect Arnold Eisen said in an

interview. Mr. Eisen said he personally favored ordaining gay rabbis as long as

it was permissible according to Jewish law and the faculty approved.

“I’ve been asking the faculty, and time and again I got the same answer,” Mr.

Eisen said. “People don’t know what they themselves think, and they don’t know

what their colleagues are thinking. There’s never been a discussion like this

before about this issue.”

The law committee has passed contradictory rulings before, on issues like

whether it is permissible to drive to synagogue on the Sabbath. But the opinions

it approved on Wednesday reflect the law committee’s split on homosexuality.

The one written by Rabbi Roth upholds the prohibition on gay rabbis that the

committee passed overwhelmingly in 1992. Another rebuts the idea that

homosexuality is biologically ingrained in every case, and suggests that some

gay people could undergo “reparative therapy” to change their sexuality.

The ruling accepting gay rabbis is itself a compromise. It favors ordaining gay

rabbis and blessing same-sex unions, as long as the men do not practice sodomy.

Committee members said that, in practice, it is a prohibition that will never be

policed. The ruling was intended to open the door to gay people while conforming

to rabbinic interpretations of the biblical passage in Leviticus which says, “Do

not lie with a male as one lies with a woman; it is an abomination.”

The committee also rejected two measures that argued for a complete lifting of

the prohibition on homosexuality, after deciding that both amounted to a “fix”

of existing Jewish law, a higher level of change that requires 13 votes to pass,

which they did not receive.

Rabbi Gordon Tucker, the author of one of the rejected opinions, said he was

satisfied with the compromise measure. “In effect, there isn’t any real

practical difference,” he said.

The Conservative movement was once the dominant stream in American Judaism but

is now second in numbers to the Reform movement. Conservative Judaism has lost

members in the last two decades to branches on the left and the right. Pamela S.

Nadell, a professor of history and director of the Jewish Studies program at

American University, said, “The conservative movement is wrestling with the

whole question of how it defines itself, whether it still defines itself as a

halachic movement, and that’s why there was so much debate and angst over this.”

Conservative Jews

Allow Gay Rabbis and Unions, NYT, 7.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/07/us/07jews.html

Justices to Decide if Citizens May Challenge White

House’s Religion-Based Initiative

December 2, 2006

The New York Times

By LINDA GREENHOUSE

WASHINGTON, Dec. 1 — The Supreme Court agreed Friday to

decide whether private citizens are entitled to go to court to challenge

activities of the White House office in charge of the Bush administration’s

religion-based initiative.

A lower court had blocked a lawsuit challenging conferences the White House

office holds for the purpose of teaching religious organizations how to apply

and compete for federal grants. That constitutional challenge, by a group

advocating the strict separation of church and state, was reinstated by an

appeals court; the administration in turn appealed to the Supreme Court.

The case is one of three appeals the justices added to their calendar for

argument in February. A question in one of the other cases is whether a public

school principal in Juneau, Alaska, violated a student’s free-speech rights by