|

History > 2006 > USA > Faith, Sects (IV)

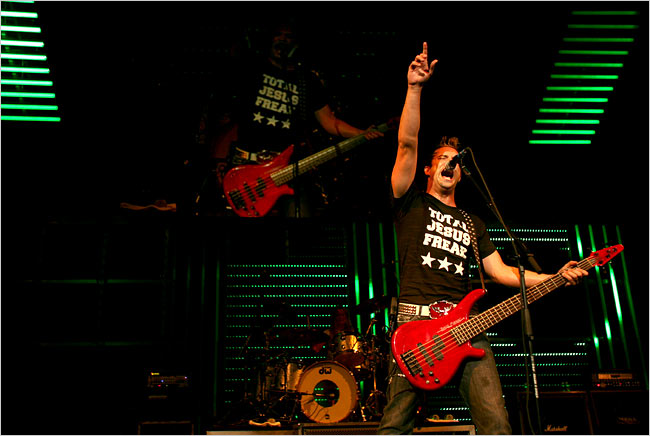

John Cooper of the Christian rock band

Skillet

at last month’s Acquire the Fire event in Massachusetts

for evangelical

teenagers.

Photograph: Erik Jacobs for The New York Times

Evangelicals Fear the Loss of Their

Teenagers

NYT

6.10.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/06/us/06evangelical.html

Some Protestant churches feeling 'mainline'

again

Updated 10/31/2006 9:51 PM ET

USA Today

By Cathy Lynn Grossman

YORKTOWN, Va. — St. Mark Evangelical Lutheran Church in

this historic southern Virginia town welcomed 24 new members last month — a tiny

breath of life in a denomination faced with a daunting decline in national

membership.

Next week, when Virginians vote in 2006's divisive midterm

elections, the people of St. Mark may split "red" conservative or "blue"

liberal. But when they gather to pray, this is a "purple" place, red and blue

mixing in the pews.

"God is calling us to something bigger than just our political views," says the

Rev. Gary Erdos, pastor of St. Mark.

It is classic mainline Protestant in nearly every respect:

It embraces an interpretive approach to Scripture rather than taking the Bible

literally. It makes a strong commitment to social justice and social action

drawn from Gospel teachings.

Classic in every respect but one: St. Mark is growing. Membership has jumped

from 500 to 1,200 people since 1997, and Sunday attendance climbed from 200 to

500.

By comparison, total membership in the seven largest mainline Protestant

denominations — United Methodist, Evangelical Lutheran, Episcopal, Presbyterian

Church (USA), Disciples of Christ, United Church of Christ and American Baptist

Churches — fell a total of 7.4% from 1995 to 2004, based on tallies reported to

the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches.

Meanwhile, the total membership count for Roman Catholics, the

ultra-conservative Southern Baptist Convention, Pentecostal Assemblies of God

and proselytizing Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) reported

to the Yearbook is up nearly 11.4% for the same period.

Yet church historian Diana Butler Bass argues that St. Mark is not an anomaly

but a signpost of revival. It's living proof that headline-dominating

conservative and fundamentalist churches aren't the only face of American

Christianity.

In her new book, Christianity for the Rest of Us, Bass visits churches coast to

coast to bolster her claim that the mainline is not dead — yet.

"Mainline" is shorthand among historians, statisticians and theologians for the

Protestant faiths of the Founding Fathers, housed in landmark churches on

downtown corners, still preaching the social justice teachings that have shaped

many political, academic and philanthropic leaders to this day.

Bass set out on a Lilly Foundation grant to find 50 mainline churches rooted in

the Gospel, rich in worship, strong in social justice, creative in spirituality

and radiating hospitality. Instead, she found 1,000 thriving congregations from

California to Virginia. St. Mark, nestled in the town where the British

surrendered to Colonial forces 225 years ago, is one of the 10 churches

highlighted in her book.

Erdos says "orthodox preaching, hospitality and attention to details" enable St.

Mark to prosper. "We hew to the gospel of Jesus. It's the reason we exist, or

we'd just be Habitat for Humanity doing good things."

Under the high wooden beams of its simple sanctuary, St. Mark offers a

traditional service, with a pipe organ sounding.

"We chant and stand in a line of Christians who, for 1,700 years, have been

saying 'Lord have mercy' in a way that a praise band and a PowerPoint

presentation just don't do," Erdos says.

The church's welcome is exemplified in Cafe St. Mark, set up twice a week in the

atrium. Staff and volunteers cook and serve a bountiful buffet, including

waffles and omelets cooked to order, every Sunday morning.

It's free to visitors and a nominal charge to members, as are the Wednesday

restaurant-style dinners offered so families can socialize and still be on time

to Bible study or hand-bell choir rehearsal.

"We pay attention to the small things that show respect. Our worship doesn't

sound or look like a third-rate high school play. There are no typos in the

newsletter or half-hearted sermons," says Erdos, who preaches without notes,

roaming the front of the pews.

"I don't want a rock 'n' roll service," says Tammy Held, head of the church

council, who loves the formal style, age-old hymns and prayer-laden liturgy and

programs. "I really welcomed the 10-day prayer vigil we're doing right now on

stewardship in the church. It works for coming close to God, closer to the Bible

and closer to each other."

Erdos designed another reason for growth right into the glass-walled atrium that

connects the sanctuary with a new education and office wing. The view is all

trees and traffic, nature and passing humanity. "I want us to see each other and

to see out all the time.

"What makes us different than the evangelical church down the road?" he asks

during a recent sermon. "My goal is to equip you to go back into the world, to

equip you for life, health and wholeness. You come here for support and prayer

in this journey."

Threats from left and right

Yorktown is within an hour of the Rev. Pat Robertson's ultra-conservative,

Republican-leaning media and ministry empire. But it's a world away in

philosophy.

Had Dan Cummins and his wife, Karen, found politics in the pulpit and pews of

St. Mark — people telling them and their two teenage sons how to vote or what to

think about Iraq, homosexuality, the environment or other hot issues — "We'd

have never joined," he says.

The Cummins family and 20 other people joined the church in late October after

the adults completed one of the four-week classes, held several times a year, in

Lutheran theology and the practices, ministries and missions at St. Mark.

It will take this kind of proactive energy to stem a 15-year-drop in membership

in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, said presiding bishop Rev. Mark

Hanson in a state-of-the-church address to a McLean, Va., church last month.

He cited twin threats: the growing strength of the theological conservatives on

the right and the lure of unchurched spirituality and secularism on the left.

About one in three U.S. Christians identify themselves in national surveys as

conservative evangelical Protestants, whose loudest voices Hanson calls

"fundamentalist." Yet, Hanson said, "I hear voices everywhere saying that the

fundamentalist image of Christianity is 'not who I am.' "

And 10% to 14% of Americans, depending on the survey, say they have no religious

identity.

"We got lazy. We waited for the culture to produce Christians for us. It's not

going to happen," Hanson said. Of his own six children, ages 18 to 30, "I bet my

bottom dollar only two are in worship today."

Says Eileen Lindner, editor of the 2006 Yearbook of American and Canadian

Churches, "There's a wholesale decline in denominational clout, no matter what

brand. Denominations have lost the power to enforce theological conformity or

regulate the actions of local congregations, and they've ceded their service

programs to relatively new organizations such as Habitat for Humanity, Heifer

International or Bread for the World."

Sociologist Barry Kosmin, a lead researcher for the American Religious

Identification Survey, done in 1990 and 2001, says, "The mainline is never going

to be the dominant cultural group again.

"But neither is anyone else in this highly fragmented, segmented market."

In 2001, 17.2 million people named a mainline denomination, down from 18.7

million in 1990. "It's the same thing you have with television," says Kosmin,

co-author of Religion in a Free Market, which analyzed the 2001 research.

"You once had three or four networks. Now you have 500 channels."

Still, the experts say hold off on playing taps for the mainline. "Numbers

aren't the only story," Lindner says. "We still have to talk about what really

counts — cultural hegemony."

Faith and the Founding Fathers

The mainline churches are still landmarks on the landscape of the city squares.

Their ideas were formative in the historic documents dating to the Declaration

of Independence. And members are still bellwethers, opinion makers in politics,

philanthropy, education and activism for social justice.

"Just because a denomination looks like it's dying out doesn't mean there

actually is less mainlinereligion out there," says Baylor University sociologist

Paul Froese.

Baylor's national survey, released in September, found 26.1% of Americans

described themselves as mainline in general. When asked to name a denomination,

22.1% named a mainline brand.

"You are always going to have a third to a quarter of American churches who call

themselves theologically liberal, that offer solid religious ethics and meet the

needs of a population less absolute in their moral outlook and less likely to

believe literally in the Bible," Froese says.

Bass sees an analogy to the Dr. Seuss classic children's book Horton Hears a

Who!

Horton the elephant hears the voices of the "Who," creatures so tiny no one can

see them. Just as the Who face extinction, he persuades all the Who to shout at

once, to be strong enough to be heard and thereby survive.

Mainline congregations, says Bass, "have a beautiful world where they are

enacting service, doing justice, learning to pray and caring for one another.

And no one seems to realize they are there."

Some Protestant

churches feeling 'mainline' again, UT, 31.10.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2006-10-31-protestant-cover_x.htm

In Ohio, Democrats Show a Religious Side to

Voters

October 31, 2006

The New York Times

By DAVID KIRKPATRICK

COLUMBUS, Ohio, Oct. 30 — Representative Ted

Strickland, an Ohio Democrat and former Methodist minister, opened his campaign

for governor with a commercial on Christian radio vowing that “biblical

principles” would guide him in office.

In his first major campaign speech, Mr. Strickland said “the example of Jesus”

had led him into public service. He has made words from the prophet Micah a

touchstone of his campaign.

Ohio, where a groundswell of conservative Christian support helped push

President Bush to re-election two years ago, has become the leading edge of

national Democratic efforts to win over religious voters, including

evangelicals.

Explaining his hope to win conservative Christian votes, Mr. Strickland said, “I

try to make a distinction between the religious right — people who have a

conservative theological perspective — and the political religious right, who

seem to have as their primary motivation political influence.”

Polls show a notable decline since 2004 in support for Republicans among white

evangelical Christians, who make up about a quarter of the electorate. The slip

in Ohio has been especially steep. In 2004, 76 percent of white evangelical

Christians in Ohio voted for Mr. Bush over the Democratic candidate, Senator

John Kerry. But in a recent New York Times/CBS News poll, 53 percent of the same

voters approved of the president’s performance, and 42 percent disapproved.

Democrats, meanwhile, have stepped up efforts to lure religious voters in states

including Michigan, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. But Mr. Strickland has

capitalized more than anyone else on evangelical disaffection from the

Republicans, helping to give him a lead of more than 20 percentage points in the

race.

Mr. Strickland faces a Republican opponent, J. Kenneth Blackwell, who speaks

just as openly about his evangelical faith, staunchly opposes abortion rights

and same-sex unions and carries the endorsement of several nationally known

Christian conservatives. But in a recent Quinnipiac University poll, Mr.

Blackwell led Mr. Strickland among white evangelical voters by only three

percentage points, which is within the margin of error.

“I have talked to lots of folks who say this is the first time they are not

voting Republican,” Rich Nathan, pastor of the Vineyard Columbus Church, one of

the largest in the state, said in an interview Sunday after a service. Mr.

Strickland, he said, was “making headway.”

Still, dozens of evangelicals interviewed at Vineyard Columbus and another

megachurch, Grace Brethren, said they remained wary of overtures from Democrats,

even Mr. Strickland. Many said they felt more repelled by the Republicans than

attracted to the Democrats.

“The Republican is lying, and the Democrats are secular,” said Joshua Porter, a

video producer attending Vineyard Columbus. “Who do we vote for?”

Robert Oser, an usher at Grace Brethren, said Mr. Strickland’s liberal positions

undercut him. “The Democrats are trying to change their spots,” Mr. Oser said,

“but their spots are still there.”

No one brought up the New Jersey Supreme Court decision to recognize some form

of same-sex unions as a factor on Election Day.

Only Mr. Oser offered the explanation for grass-roots malaise that Christian

conservative groups in Washington usually suggest: that the Republicans had not

done enough about abortion or other social issues.

Instead, some said they were disturbed by corruption in the

Republican-controlled Statehouse here and in the Republican-controlled Congress.

And many pointed to the Ohio economy, budget cuts for schools and social

services and the war in Iraq.

Lawrence Porath, a parishioner at Grace Brethren, said he called himself a

staunch Republican two years ago and helped turn out voters as a county leader

of the Christian Coalition. But a week before this year’s midterm elections, he

said he was not sure whom to vote for.

“I feel like our president has really not given us the complete truth from the

beginning, on the war, or on anything,” Mr. Porath, a commercial real estate

investor, said in an interview after services on Sunday.

Mr. Nathan of Vineyard Columbus said such disillusionment was common. “How is it

that we evangelicals have become the strongest constituency for war of any group

in America?” he asked.

When he asked that question from the pulpit, Mr. Nathan said, people stand up

and cheer.

Other Democratic candidates here are also reaching out to evangelicals and other

Christians. Until recently, Representative Sherrod Brown, a Lutheran who is

running for Senate here, seldom spoke publicly about his religious views.

This year, however, Mr. Brown’s advisers discovered that after visiting Israel a

decade ago he had written to his daughters and a Jewish friend about the

emotions he felt reading aloud from the Sermon on the Mount at the site where

Jesus is believed to have delivered it. Mr. Brown’s campaign quickly

incorporated his private words into messages sent to Christian voters.

In an interview, Mr. Brown said he now talked about his faith “a bit, not a

lot.” A campaign aide then arranged a second interview with Mr. Brown’s wife,

Connie Schultz, who said her husband tithed, listened to Lutheran hymns to relax

and prayed before each campaign debate.

Mara Vanderslice, an evangelical Protestant who worked on Senator Kerry’s

presidential campaign, has opened a consulting firm, Common Good Strategies,

based here, to help Democrats across the country reach religious voters and, she

said, to help make the party more welcoming to them.

In addition to working with Mr. Strickland and Mr. Brown, Ms. Vanderslice is

consulting with Democrats in Alabama, Michigan, Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

The Michigan Democratic Party consulted with 500 members of the clergy,

including many evangelical Christians, and revised its platform. The revision

included a dedication: “The Common Good. The best for each person in the state.

The orphan. The family. The sick. The healthy. The wealthy. The poor. The

citizen. The stranger. The First. The Last.”

At a speech this month at a Lutheran college here, Mr. Strickland put a liberal

twist on the common conservative Christian theme about secular forces trying to

squeeze religion from the public square.

“There are those in Columbus and elsewhere who argue that the biblical mandates

to love your neighbor and to work for justice are meant only for individuals and

have no application to the political sphere,” Mr. Strickland said. “They dismiss

the Democrats and those religious leaders who claim that our faith requires us

to insist that governments and government leaders — not just private citizens —

seek justice, love, mercy, and humbly work to help the least, the last and the

lost in our society.”

In an interview, Mr. Strickland said that Christian conservatives had a right to

their interpretation of the Bible, but that “it is an anemic interpretation, at

best.”

Phil Burress, president of Citizens for Community Values and a prominent

Christian conservative organizer here, accused Mr. Strickland of using his

faith. “He abandoned his theology degree,” Mr. Burress said, “and all of a

sudden he has found that it is a good political toy.”

Still, Mr. Burress commended the Democrats for at least competing for

conservative Christian voters. And, he added, “if he is successful in breaking

into that bloc of voters, it is going to be a very interesting 2008.”

In

Ohio, Democrats Show a Religious Side to Voters, NYT, 31.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/31/us/politics/31church.html

Bishops Draft Rules on Ministering to Gays

October 29, 2006

The New York Times

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN

The nation’s Roman Catholic bishops have

drafted new guidelines for ministry to gay people that affirm church teaching

against same-sex relationships, marriages and adoptions by gay couples, yet

encourage parishes to reach out to gay Catholics who feel alienated by their

church.

The bishops’ document, the result of a four-year effort, gives specific

instructions on some of the conundrums now faced in many parishes.

The guidelines recommend baptizing the adopted children of same-sex couples, as

long as the children will be raised as Catholics. It says that gay people may

benefit from revealing their “tendencies” to friends, family and their priest,

but should not make “general public announcements” about it in the parish.

The guidelines also say that gay men and lesbians have “no moral obligation to

attempt” therapy, an apparent reference to therapy programs that claim to change

gay people’s sexual orientation. It says that while “some have found therapy

helpful,” there is “no scientific consensus” either on therapy or the causes of

homosexuality.

The bishops will vote on the document — “Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual

Inclination: Guidelines for Pastoral Care” — when the United States Conference

of Catholic Bishops meets Nov. 13-16 in Baltimore. It could be amended, and

needs a two-thirds majority to pass.

Bishop Arthur J. Serratelli of Paterson, N.J., the chairman of the bishops

doctrine committee, which wrote the new guidelines, said that although it was

difficult to predict whether it would pass, “It’s a very sound document, a very

clear document. My sense is that the bishops will readily embrace it.”

Gay Catholic leaders who had read the draft, however, predicted that it would

only further alienate gays and their families from the church.

“There certainly is some lovely language that sounds welcoming in here,” said

Sam Sinnett, president of DignityUSA, an organization for gay Catholics, “but

essentially they’re repeating all the spiritually violent things they’ve been

saying about gay and lesbian Catholics for a couple of decades — that we are

‘objectively disordered’ and our relationships are intrinsically evil.”

A previous document, issued by a committee of bishops in 1997, was directed

primarily at parents with gay children. But it proved controversial and was

never approved by the bishops conference.

This new document puts more emphasis on the church’s moral teaching about

sexuality. It says that although having a “homosexual inclination” is not itself

a sin, homosexual sex is a sin — as are premarital sex and adultery. The answer

in all these situations is chastity.

The document says that although the church teaches that homosexuality is

“objectively disordered” — a teaching in the catechism that says homosexual acts

violate the natural law — the church is not saying that homosexual people

themselves are disordered or “rendered morally defective by this inclination.”

Such distinctions will provide little comfort to gay Catholics, said Francis

DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways Ministry, a gay outreach group for

Catholics based in Maryland. Mr. DeBernardo criticized the document for saying

that gay people should make their sexuality known only to a small group, and

that gay people whose behavior “violates” church teaching should be denied

leadership roles in parishes.

“Gay and lesbian people are going to read those remarks and see them as

offensive, as telling them to go underground,” he said.

That is not the intention, said the Rev. Thomas G. Weinandy, who worked on the

document as executive director for the United States bishops’ secretariat for

doctrine and pastoral practices.

“The bishops would like people with homosexual inclinations to really

participate in the church, but they don’t want to ‘give scandal,’ ” Father

Weinandy said. “If you knew a heterosexual couple were just cohabitating and not

married, you wouldn’t let them be eucharistic ministers either.”

The Rev. James Martin, an editor at the Jesuit magazine America, said, “The

document expresses the tension in the church between a sincere desire to

minister to gays and lesbians, and the reality that many gays and lesbians feel

unwelcome in the church by virtue of the church’s teaching.”

The bishops have issued statements in recent years condemning gay marriage, gay

adoption and benefits for gay partners. They have historically been more attuned

to gay issues, however, than some of their colleagues overseas. Last year, the

Vatican issued an “instruction” saying that men with “deep-seated” homosexual

attraction should not be ordained. In its wake, some American bishops commented

in their diocesan newspapers or privately to their priests that they did not

regard this as a ban on ordaining gay men, and would continue to accept gay

candidates on a case-by-case basis.

The bishops said they felt the need for clear guidelines because there were many

pastoral ministries for gay people in parishes and dioceses around the country,

and “confusion” about what was an “authentic” Catholic approach, Father Weinandy

said. He noted that the Vatican had disciplined the founders of New Ways

Ministry, the Rev. Robert Nugent and Sister Jeannine Gramick, for preaching

acceptance of gay relationships.

As such, the guidelines repeatedly say that bishops should not countenance

church leaders and pastoral workers who fail to uphold its teachings on

homosexuality, or who advocate harm toward gay people.

It says, “The church cannot support organizations or individuals whose work

contradicts, is ambiguous about, or neglects her teaching on sexuality.”

Bishops Draft Rules on Ministering to Gays, NYT, 29.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/us/29bishops.html

Los Angeles Abuse Cases Are Settled for $10

Million

October 28, 2006

The New York Times

By NEELA BANERJEE

WASHINGTON, Oct. 27 — The Roman Catholic

Archdiocese of Los Angeles and a Catholic religious order have agreed to pay $10

million to settle claims made by seven victims of sexual abuse by clergy

members, lawyers for the parties involved said Friday.

While the amount per victim is large relative to payments made to settle sexual

abuse cases in other parts of the country, it is typical of the sums paid in

California, which has a taken a strong stance toward the Catholic Church in

abuse cases. In 2003, for example, the state extended its statute of limitations

for child sexual abuse cases, and the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office has

been conducting a criminal investigation into the archdiocese since 2002.

More than 95 percent of the $10 million settlement will be paid by the religious

order, the Carmelites, Province of the Most Pure Heart of Mary, which is based

in Darien, Ill. The archdiocese will pay less than 5 percent, lawyers for the

plaintiffs and the order said.

The settlement for the most part is not covered by the Carmelites’ insurance,

said Jim Geoly, the order’s lawyer, adding that the order might have to borrow

money to pay the sum.

Mr. Geoly said the order wanted to avoid protracted litigation, which he said

would have amounted to going to war with the plaintiffs, “because that’s what

litigation is.”

“They are deeply sorry that this sexual abuse occurred and that the church

didn’t have more understanding of this kind of problem at the time,” he said.

“They want to do everything they can to make it right, even though money can’t

make the abuse go away.”

The seven plaintiffs accused four Carmelite priests and one Carmelite brother of

sexual abuse in a period from the early 1950s to the late 1970s.

Several of the claims focused on the Rev. Dominic Savino, who held several

high-ranking faculty positions at Crespi Carmelite High School in the Encino

section of the city before he was removed from the ministry in 2002. One

plaintiff accused Father Savino and another priest of raping him at the school

when he was 15 and continuing the abuse from 1978 to 1979, said John C. Manly, a

lawyer for the plaintiff.

Mr. Manly and victims’ rights groups welcomed the decision by the Carmelites,

though they said that it had been hard-won.

“I’m glad Carmelites did the right thing,” said Mr. Manly, himself a Catholic,

“but I think that’s what’s ultimately wrong with the Catholic Church: you

shouldn’t have to sue your church to get them and the bishop to do the right

thing.”

Los

Angeles Abuse Cases Are Settled for $10 Million, NYT, 28.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/28/us/28settle.html

Taking On a Coal Mining Practice as a

Matter of Faith

October 28, 2006

The New York Times

By NEELA BANERJEE

HALE GAP, Va. — The windswept ridge that

Sharman Chapman-Crane hiked to on a recent fall afternoon is the kind of place,

she said, that she normally would avoid. From there, she could see what she

loved about Appalachia and what it had lost, and she wanted her visitors to see

it, too.

The old rounded peaks of the mountains encircled the ridge, dense with trees

smudged red and gold. But in the middle of the peaks, several stood stripped

bare and chopped up, a result of an increasingly common and controversial coal

mining practice called mountaintop removal.

“Doesn’t it say in Scripture, ‘Who can weigh a mountain, measure a basket of

earth?’ ” Ms. Chapman-Crane said, recalling descriptions of God’s omnipotence in

Isaiah 40:12. “Well, only God can. But now, the coal companies seem to be able

to do it, too.”

Ms. Chapman-Crane, her colleagues at the Mennonite Central Committee Appalachia

and other Appalachian Christians are trying to halt mountaintop removal, and at

the heart of their work, they say, is their faith.

They are part of an awakening among religious people to environmental issues,

said Paul Gorman, executive director of the National Religious Partnership for

the Environment, an interreligious alliance. Increasingly, religious people

across denominations are organizing around local issues, like preventing a

landfill, preserving wetlands and changing mining.

“People of faith are thinking afresh about human place and purpose in the

greater web of life,” Mr. Gorman said. “They are asking, What does it mean to be

present in a crisis of God’s creation made by God’s children?”

Although Christian environmental activists speak out against mountaintop removal

at different levels of government, many believe that showing the practice’s toll

will persuade others to join them in seeking stricter regulation of it, if not

an outright ban.

A new group, Christians for the Mountains, urges religious people to take up

mountaintop removal “as a spiritual issue,” and it has made a DVD that it is

distributing to churches and individuals, said Allen Johnson, an evangelical

Christian and a founder of the group.

The Rev. John Rausch, director of the Catholic Committee of Appalachia, has led

tours of mountaintop removal sites since 1994. Mr. Rausch estimates that 400

people have taken his tour. They learn of the tours by word of mouth or from

their churches, pay a few hundred dollars to stay in simple accommodations, hike

several miles through forests and mined lands and talk to people whose lives

have been affected by mountaintop removal.

The Mennonite Central Committee Appalachia, based in Whitesburg, Ky., gave its

first tour in October, focusing on a corner of southeastern Kentucky and

southwestern Virginia rich in coal and diverse forests.

On the second morning of the four-day tour, the trip’s leaders, Ms.

Chapman-Crane and the Rev. Duane Beachey, marched their three-member group up

the mile-long trail to Bad Branch Falls. Poplars, beeches, hemlocks and

magnolias thatched together a canopy above the trail, and the rain of their

leaves made a soft ticking sound. Wild ginseng and wintergreen lined the path.

Cottage-size boulders leaned forward over a rushing stream below the trail.

“Not every place on the mountains has waterfalls like Bad Branch,” Ms.

Chapman-Crane said. “But this is pretty much what it’s like on the mountains

here. The forests of the Appalachian range are like a northern rain forest.”

Mary Yoder, who had volunteered to come on the trip for her congregation,

Columbus Mennonite Church in Columbus, Ohio, asked, “So this is the kind of

place that gets blown up in mountaintop removal?”

Mr. Chapman-Crane replied, “This is what would be lost, is lost, when they blast

a mountaintop.”

The United States is rich with coal, and mountaintop removal has begun to

replace underground mining in Appalachia as the preferred method of extraction

because of its efficiency and lower cost. Mountaintop removal involves leveling

mountains with explosives to reach seams of coal. The debris that had once been

the mountain is usually dumped by bulldozers and huge trucks into neighboring

valleys, burying streams.

The coal industry asserts that mountaintop removal is a safer way to remove coal

than sending miners underground and that without it, companies would have to

close mines and lay off workers.

Luke Popovich, a spokesman for the National Mining Association, a coal lobbying

group, said that by fighting mountaintop removal religious groups might find

their priorities colliding.

“They find themselves in a difficult position,” Mr. Popovich said, “because

they’re expressing support for those who purport to protect nature, and, at the

same time, that activism carries implications for the human side of the natural

equation. Human welfare depends on the rational exploitation of nature.”

Christianity runs wide and deep in Appalachia. At the Courthouse Cafe in

Whitesburg, Mr. Beachey explained that as a Christian concern for his neighbors

drove his desire to rein in mountaintop removal. But as in much of Appalachia,

pastors and churchgoers here are reluctant to stir up trouble: many work for

coal companies, or the people next to them in the pew do. Others believe

stopping mountaintop removal would eliminate the few jobs that remain.

Many understand their faith differently than Christian environmentalists do. One

night, Darrell Caudill and several friends gathered to play their guitars for

the environmental tour and sing traditional songs and hymns. Mr. Caudill, 57,

works for a coal company and believes in being a good steward of the earth. But

to him, he said, being a Christian means being saved and spreading the Gospel.

There is no tension between being committed to his faith and supporting

mountaintop removal.

“Why did God produce coal then and put it underground?” said Mr. Caudill, who

attends a nondenominational evangelical church. “He produced things that we need

on this earth. Without coal, you wouldn’t have the warmth and light you have

right now.”

Late in the trip, the tour group drove Lucious Thompson, 63, a former coal

miner, to the horseshoe of peaks above McRoberts, where he lives. The peaks have

been leveled. The woods where he had hunted are gone. The new grass on the new

plateaus barely clings to the soil, which means that McRoberts often floods now

after hard rains, he said.

“I’ve been flooded three times since they started working on the mountaintop,”

Mr. Thompson said.

He talked of neighbors whose house foundations had been cracked because of the

daily blasting, of a pond lost to sludge and of respiratory ailments because of

the coal dust flying from the coal trucks.

“The coal company says it’s God’s will,” he said. “Well, God ain’t ever run no

bulldozer.”

People like Mr. Thompson and the woods and mountains of Appalachia seemed to

make the point the tour’s organizers hoped for. After the tour, Ms. Yoder

returned to Columbus to tell her congregation of about 200 what she had learned.

“My comment to the church was that I would do the tour with an open mind,” she

said, “and my conclusion is there is no room for mountaintop removal in our

country.”

Taking On a Coal Mining Practice as a Matter of Faith, NYT, 28.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/28/us/28mountains.html?hp&ex=1162094400&en=08c7ce06e6fb8d86&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Watchdog Group Accuses Churches of

Political Action

October 26, 2006

The New York Times

By STEPHANIE STROM

A nonprofit group has filed a complaint asking

the Internal Revenue Service to investigate the role that two churches may have

played in the re-election campaign of Kansas’ attorney general.

The complaint by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a

nonpartisan legal watchdog organization, cited a memorandum from the attorney

general, Phill Kline, a Republican, directing members of his campaign staff to

recruit churches to distribute campaign literature and serve as the sites for

events.

“This is the top law enforcement official in the state who is encouraging

everyone to break the law,” said Melanie Sloan, executive director of the

watchdog group. “He’s either abysmally unfamiliar with the law, or he’s

deliberately violating it.”

A spokeswoman for Mr. Kline, Sherriene Jones, did not return calls to her

office.

In his memorandum, Mr. Kline identified two Topeka churches, the Light of the

World Christian Center and the Wanamaker Woods Church of the Nazarene, which he

said had participated in “lit drops” by handing out campaign literature. A woman

who answered the telephone at Wanamaker Woods Church said the church had no

comment.

The Rev. Greg Varney, pastor of Light of the World Christian Center, issued a

statement saying that Mr. Kline had preached at the church on July 9, but

insisting that no illegal activity had occurred. “At no time here at our church

did Phill bring up politics, re-election or campaign contributions,” the

statement said.

Mark W. Everson, the commissioner of the I.R.S., has repeatedly warned that the

agency will crack down on religious organizations that violate laws barring

charities of any type from involvement in partisan political activities.

This election cycle, additional accusations of such violations have been made

against religious organizations in California, Minnesota, Missouri and Ohio.

Whether the I.R.S. has responded to those complaints is unknown; the agency is

barred by law from disclosing its investigations.

All Saints Church, an Episcopal congregation in Pasadena, Calif., has said it

was under investigation, but no other church named in complaints that have

become public has acknowledged an I.R.S. inquiry.

Despite a report last year by the Treasury Department’s inspector general that

concluded political considerations had played no role in the I.R.S.’s selection

of nonprofit groups for review, the agency’s silence regarding its

investigations has led to accusations of political bias.

“From what we know, the I.R.S. has gone after liberal organizations primarily,

the N.A.A.C.P. and the liberal church in California,” Ms. Sloan said, referring

to the inquiry into All Saints Church. An I.R.S. investigation of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People was closed with no finding of

wrongdoing.

“Clearly, there are violations on the conservative side, and no action appears

to be taken.” Ms. Sloan said. “If they’re being even-handed,” she added, “I

certainly can’t tell.”

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington also filed a complaint with

the I.R.S. last week against the Living Word Christian Center in Brooklyn Park,

Minn., accusing its senior pastor of violating the law by openly stating his

support for a Congressional candidate.

“We can’t publicly endorse as a church, and would not for any candidate,” the

senior pastor, the Rev. Mac Hammond, told his congregation during a service on

Oct. 14 as he introduced Michele Bachmann, a Republican state senator who is

running for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. “But I can

tell you personally that I’m going to vote for Michele Bachmann,” he said.

During her remarks that followed, Ms. Bachmann said that she had been called by

God to run for the House seat after three days of fasting and praying with her

husband.

The Star Tribune in Minneapolis later reported that Mr. Hammond could not vote

for Ms. Bachmann because he does not live in her district.

Mr. Hammond did not respond to messages seeking comment.

The Star Tribune quoted Mr. Hammond as saying he had “learned my lesson.”

Watchdog Group Accuses Churches of Political Action, NYT, 26.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/26/washington/26church.html

1867 Mormon Tabernacle Pews

Are Casualties

of a Face-Lift

October 26, 2006

The New York Times

By MARTIN STOLZ

SALT LAKE CITY, Oct. 25 — When the historic

Tabernacle, the egg-shaped building that is home to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir,

reopens next year after a lengthy face-lift and seismic retrofit, visitors will

find something new: the pews.

The loss of the original, and uncomfortable, pine pews, handmade in 1867 and

meticulously etched and painted to look like oak, angers many Mormons, whose

religion is strongly defined by its history and its forebears’ hardships.

Kim Farah, a spokeswoman for the Mormon Church (officially known as the Church

of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), released a two-sentence statement saying

some original pews — Ms. Farah would not say how many — would be returned and

that others would be replaced with oak copies “to maintain historicity.” “No

determination has been made on what will happen to the unused original benches,”

the statement said.

Church officials would not give an explanation for the change, Ms. Farah said in

an interview.

“The church is circumspect about the pews, because it is a work in progress,”

she said of the Tabernacle renovations, including the pews.

Lack of an explanation angered LaMar Taft Merrill Jr., a retired schoolteacher

who grew up here and lives in Lexington, Ky. Mr. Merrill, a descendant of an

early church apostle, said not returning the pine pews would be a “shameful act”

by the church’s “misguided top echelon.”

“You can’t ever replace what’s original,” he said. “And an oak bench is no more

comfortable than a pine bench.”

A professor of architectural history at the University of Utah, Thomas R.

Carter, said the Tabernacle design reflected “the innovation and creativity of

the early church.” “It’s experiential,” Professor Carter said. “When I’m there,

I feel like, wow, this is such a monumental achievement for the time. And the

style is so radical. It’s not a different kind of church. It’s an other. It is

otherness.”

Professor Carter, a Presbyterian, said he did not have strong feelings about the

pews. He suggested that Tabernacle users could consider the bench dispute based

on “what they feel through their bottoms, whether they feel uncomfortable or a

connection to the past.”

The early Mormons who made their way west and established Salt Lake City in 1847

believed that they were building a holy “kingdom in the tops of the mountains,”

a place to live and welcome their savior with suitable edifices, said Jan

Shipps, an emeritus professor of Mormon history and religion at Indiana

University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

“Their fervor, it was amazing,” Ms. Shipps said. “They understood themselves to

be going to the Promised Land.”

In April 1867, the Mormon leader, Brigham Young, exhorted thousands of the

faithful to donate labor and supplies to help furnish the interior with pews.

Hundreds of volunteers heeded the call. Six months later, the Tabernacle had

seating for nearly 9,000. Thousands of pines from the Wasatch Mountains to the

east were felled, milled and hauled overland.

Because Young wanted the pews to look as if they were fashioned from oak, the

volunteers, including Edward William Davis, a skilled carpenter, painter and

glazer from England, created faux grains in the wood, using chisels to etch and

feathers or combs to paint the 290,000 feet of the plain pine to resemble oak.

Graining, as the 19th-century practice is known, was common, but the scale of

the pew project here is impressive, said Carol Edison, manager of the folk art

program at the Utah Arts Council. Mr. Davis’s great-great-grandson, David

Ericson, an art dealer here, called the pews “the character-defining attribute”

of the Tabernacle. If they go, Mr. Ericson said, “you lose your access to that

indigenous past.”

Ms. Edison voiced hope that the old pews would be preserved and reused in other

historic Utah buildings.

The church has added controversy by announcing this month that it plans to tear

down three historical structures it owns, including the 14-story Greek Revival

First Security Bank tower of 1919. The demolition would make way for a $1

billion retail, office and residential complex, the largest development project

in the city’s history, on 25 acres opposite Mormon headquarters.

The prospect of losing the ornately decorated bank building dismays

preservationists. “We think the building is one of the social and historical and

architectural icons of downtown,” Kirk Huffaker, interim executive director of

the Utah Heritage Foundation, said.

On Oct. 18, an official of the church’s real estate development company, Mark

Gibbons, told City Council members that the church had decided, for now, to

postpone leveling the bank and would re-evaluate its plan, though “all options

are on the table.”

The state historic preservation officer, Wilson G. Martin, said the state hoped

that the church would “tweak” its plans and save the bank. But his agency, the

Division of State History, has no position on the Tabernacle pews, Mr. Martin

said, because interiors of functioning historic buildings change frequently, and

he considers the pews interior furniture.

For Robert Charles Mitchell, a retired newspaper editor from Salt Lake City who

lives in Logan, the fate of the pews and the bank tower hit the “same vein.”

“It’s an issue of values,” he said. “We glorify our pioneers. We talk about

their travails and bless their devilishly hard work. We laud them on the one

hand and run roughshod over them on the other. We’re dishing up ersatz history

and throwing away the real thing.”

1867

Mormon Tabernacle Pews Are Casualties of a Face-Lift, NYT, 26.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/26/us/26pews.html

Connecticut Episcopal Bishop Will Bless Gay

Unions

October 23, 2006

The New York Times

By FERNANDA SANTOS

The leader of the Episcopal Diocese of

Connecticut, Bishop Andrew D. Smith, has authorized priests to give blessings to

same-sex unions during religious ceremonies. The move threatens to further

alienate the conservative wing of his church and deepen a fissure between

progressive and orthodox Episcopalians nationwide.

“I believe in my heart and soul that it is time for this church, this diocese,

formally to acknowledge and support and bless our sisters and brothers who are

gay and lesbian, including those who are living in faithful and faith-filled

committed partnerships,” Bishop Smith said on Saturday in a speech at a diocesan

conference in Hartford.

The decision, reported yesterday by The Hartford Courant, does not authorize

Episcopal clergy to officiate at civil unions or create an official prayer

service for the blessings. Rather, it permits parishes to acknowledge gay and

lesbian couples who have had a civil union granted by the state. Connecticut

approved civil unions last year.

The decision allows each parish to choose whether to acknowledge same-sex

couples during religious services, said Karin Hamilton, spokeswoman for the

diocese.

Nationwide, nine other Episcopal dioceses — in Arkansas, California, Delaware,

Long Island, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Vermont and Washington, D.C.

— have enacted policies allowing the blessing of same-sex couples, according to

Integrity, a national Episcopal gay organization based in Rochester. Kansas used

to have the same policy, but it was rescinded there in 2003, when the diocese

ordained a new bishop, Dean E. Wolfe.

“What happened in Connecticut is great news for the church, because what it says

is that we’re going to continue to move forward to fully include all of the

baptized in the body of Christ, whether they’re gay or straight,” said the Rev.

Susan Russell, president of Integrity and an Episcopal priest in Los Angeles.

“We should be in the business of building bridges, not walls.”

But the Rev. Canon David C. Anderson, president of the American Anglican

Council, an orthodox umbrella group, said that Bishop Smith’s decision “is proof

of his disregard for the larger Anglican Communion and further evidences his

militancy with the homosexual gay agenda.”

“Bishop Smith and some other bishops as well are literally choosing to pull

themselves and their churches out of the broader religious community,” Canon

Anderson continued. “In the future of the Anglican community, there might be no

place for people like Bishop Smith.”

With about two million members in the United States, the Episcopal Church has

taken significant steps toward inclusiveness in the past few years, most notably

with the election of V. Gene Robinson in 2003 as bishop of New Hampshire, the

first openly gay bishop in the history of the denomination.

The same year, clergy and laymen overwhelmingly approved a resolution that

recognized the blessing of same-sex unions as a prerogative of individual

parishes.

The moves strained relations between congregations in the United States and

those in the global, more traditional, Anglican Communion, of which the

Episcopal Church is the American arm.

A 2004 report commissioned by the communion’s leader, the archbishop of

Canterbury, recommended that the Episcopal Church apologize for the ordination

of Bishop Robinson and stop blessing same-sex couples and electing gay bishops.

The Episcopal Church responded at its triennial conference this year, calling on

dioceses to avoid backing the election of openly gay bishops.

But in Connecticut, Bishop Smith has continued to push forward his changes, as

he has done since becoming the diocesan bishop seven years ago.

In 1999, he changed a longstanding policy to allow the ordination of gay clergy

members. In 2000, he and other religious leaders voted to extend health benefits

to the same-sex partners of diocesan employees.

“I believe that it is time for us to rethink, repray and reform our theology and

our pastoral practices; to welcome, recognize, support and bless the lives and

faith of brothers and sisters who are gay and lesbian in the equal fullness of

Christian fellowship,” Bishop Smith said in his speech, which drew effusive

cheers.

The Rev. Christopher Leighton one of six priests who rebelled against Bishop

Smith over his support of Bishop Robinson, said yesterday that Bishop Smith’s

position on the blessing of same-sex unions only complicated matters.

“He had a very fiery speech, interrupted by applause at several points and in

the end, he got a standing ovation,” said Father Leighton, of St. Paul’s

Episcopal Church in Darien. “This is where the vast majority of the diocese

stands on this matter; the problem is that the worldwide Anglican community will

have no part in this.”

Father Leighon added, “It’s not that we’re against gays. It’s rather that we’re

affirming the traditional beliefs that only a man and a woman should be intimate

for life in holy wedlock.”

Connecticut Episcopal Bishop Will Bless Gay Unions, NYT, 23.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/23/nyregion/23bishop.html?hp&ex=1161662400&en=a2be2a7204645369&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Accused Priest’s Long Flight From Law in

U.S. and Mexico

October 21, 2006

The New York Times

By JAMES C. McKINLEY Jr.

TEHUACÁN, Mexico — For two decades, dozens of

children have accused the Rev. Nicolás Aguilar of molesting or brutally raping

them. He faces an indictment charging sexual abuse in Los Angeles and at least

five formal complaints in Mexico. Yet at 65 he remains at large, still working

as a priest in villages here.

Father Aguilar’s long flight from the law, critics say, reflects the ease with

which priests can avoid prosecution in the United States by hiding in Mexico,

where judges and prosecutors are reluctant to challenge the enduring political

strength of the Roman Catholic Church.

The case has focused attention on a problem that is not limited to Father

Aguilar, but rather, critics say, points to a pattern of complicity by high

officials in the church.

In September one of Father Aguilar’s accusers filed a lawsuit in southern

California alleging that the cardinals of Mexico City and Los Angeles had

conspired to help him escape prosecution by allowing him to slip across the

border.

Both cardinals deny any wrongdoing. But American law enforcement officials and

advocates for victims say that since 1995 at least three other priests accused

of molesting children in the United States have fled to Mexico before the

authorities could arrest them. In other cases, going back to the 1980’s, still

more were transferred to Mexico after church officials received complaints about

them.

“It is symptomatic of a problem that is large and will only get larger in the

future,” said David Clohessy, director of the Survivor’s Network of Those Abused

by Priests. “More and more Catholic bishops understand these predators are hot

potatoes, and it is far safer to let them go into the third world.”

Cardinal Roger M. Mahony of Los Angeles, who leads the country’s largest Roman

Catholic archdiocese, has been accused before of sheltering priests who have sex

with children. A new documentary film, “Deliver Us From Evil,” contends that

Cardinal Mahony knew that another priest under his supervision, the Rev. Oliver

O’Grady, was abusing children in the 1980’s but moved him from parish to parish

rather than turn him in. The cardinal denies the accusation.

The other fugitives hiding in Mexico, prosecutors in the United States say, are

the Rev. Xavier Ochoa, who is wanted in Santa Rosa, Calif., on 10 counts of

forcing children to have sex with him; the Rev. Javier García, who faces 11

counts of child sex abuse in Sacramento, Calif.; and the Rev. Jesús Armando

Domínguez, who faces 58 similar charges, including forcible sodomy, in Riverside

County, Calif.

María de Jesús González, the mother of a boy in Tehuacán whom Father Aguilar is

accused of molesting in 1997, said she had given up hope that the Mexican

authorities would ever bring the priest to justice.

“Here in this world there is no justice, so I have to believe in divine

justice,” she said, angry tears welling in her eyes. “There is a religious

mafia. Among the priests, they protect each other, they help each other.”

Over the years, Father Aguilar, who began his priesthood in Mexico in 1970, has

shuffled from parish to parish under the oversight of some of Mexico’s most

prominent churchmen, even as he has been followed by many allegations of sexual

predation, critics say.

His overseers included Cardinal Norberto Rivera Carrera of Mexico City, who

heads the church in Mexico and was considered a candidate for pope last year,

advocates for victims of sexual abuse say.

Cardinal Rivera Carrera declined to be interviewed for this article. But he told

the newspaper La Prensa on Sept. 27 that he had heard “accusations of

homosexuality, but not of pedophilia” about the priest before shipping him off

to Los Angeles with a letter of recommendation. The letter said the priest

wanted a change of scene “for family and health reasons.”

In September, after protests over the case in front of the Mexico City cathedral

that drew national attention, Cardinal Rivera Carrera read a statement urging

Father Aguilar to turn himself in, “for the good of his own conscience and to

avoid more damage to the church.”

In the United States, Father Aguilar served under Cardinal Mahony in Los

Angeles. Through a spokesman, Cardinal Mahony, who is named in the civil case,

said his office reported Father Aguilar’s abuse of two altar boys to the

authorities in January 1988.

The spokesman, Tod Tamberg, said the principal of the church school left a

message on an answering machine at the office of child protective services on

the afternoon of Jan. 8 of that year; Father Aguilar left the country the next

day.

The Los Angeles police say the vicar for clergy, Msgr. Thomas Curry, tipped off

the priest on the morning of Jan. 9 that he would be investigated, two days

before their detectives were informed. Father Aguilar slipped across the border

that night.

Mr. Tamberg confirmed that Monsignor Curry had confronted Father Aguilar with

the accusations against him that morning and stripped him of ministry duty. The

priest told Monsignor Curry he was going to stay with relatives in Los Angeles

during the investigation, but he fled the country instead, Mr. Tamberg said.

“Our school officials acted appropriately,” he said, “and so did church

officials, to remove this guy from the ministry.” In the next nine years the

parents of at least five boys in Mexico have formally accused Father Aguilar of

sexual abuse or rape as he continued to work in parishes.

“The frustration is unbelievable,” said Detective Federico Sicard, the Los

Angeles investigator who has been seeking Father Aguilar for 18 years. He added:

“When things like this happen we fail them. The justice system failed these

kids.”

Father Aguilar’s troubled private life first came to light in 1987 in

Cuacnopalan, a dusty farming town where he headed a parish for more than a

decade.

Many older parishioners still defended Father Aguilar as the best priest they

ever had. But there were also hushed reports among some parents that the priest

had molested and fondled boys in the congregation, and at least one youngster,

who died of complications from AIDS in 1996, told friends that he had complained

to the diocese, town officials and residents said.

“There were a lot of comments about his relationships with the boys, that he had

problems with the youngsters,” Melquíades Alcántara, 61, recalled. Cardinal

Rivera Carrera, who was then the bishop of the Tehuacán Diocese, did not mount

an inquiry. He told La Prensa that an attack on Father Aguilar — along with

persistent rumors about his homosexuality, not pedophilia — had persuaded him to

ship the priest off to Los Angeles in early 1988.

After Father Aguilar was in Los Angeles nine months, two altar boys complained

that on several occasions he had lured them into his residence and fondled them.

Three months after the case was reported to the authorities, a grand jury

indicted Father Aguilar on 19 counts of lewd acts upon a child, involving 10

children. But by then he had fled back to Mexico. The Los Angeles authorities

immediately sought to have him indicted in México and extradited to California.

It took seven years for the Mexican attorney general’s office to issue an arrest

warrant, Detective Sicard said. Three months after it did, the statute of

limitations on the sex abuse charges ran out.

The priest was never arrested, but allegations of new abuses hounded him. In the

early 1990’s he served as the associate pastor at two churches in Mexico City.

Joaquín Aguilar Méndez, who brought the suit in Los Angeles in September, was an

altar boy at both. Mr. Aguilar Méndez says Father Aguilar brutally raped him in

October 1994 inside a rectory after he had misbehaved at Mass. He was 13.

Lawyers for Mr. Aguilar Méndez say he and his parents reported the rape to the

police three weeks later. The police did three rape tests and told them that

they had lost the results all three times, the lawsuit claims.

A prosecutor, the lawyers allege, offered the parents a bribe to drop the

charges. The parents refused, but the complaint never resulted in a trial, Mr.

Aguilar Méndez said.

In late 1995 or early 1996, Father Aguilar returned to Tehuacán, where he was

assigned to the small San Vicente Ferrer church, clergymen there said. Within a

year his parishioners were once again leveling charges of child molestation.

Four mothers filed charges of sexual abuse with the local prosecutor, though

other mothers said the number of victims was far higher. Cecilia Flores said her

son was only 10 when the priest tried to put his hand down the boy’s shorts.

“How many injustices has this priest committed?” Mrs. Flores asked.

That investigation dragged on for six years. The state judge handling the

charges, Carlos Guillermo Ramírez, has never issued an arrest warrant in three

of the cases and ruled out rape charges in all of them.

Even as the investigation was proceeding, Archbishop Rosendo Huesca Pacheco of

Puebla, just 71 miles away, gave Father Aguilar permission in 2001 to serve as

an assistant priest in another village. “We didn’t know there were charges

against him,” said an official in the Puebla archdiocese, the Rev. Amador Tapia.

In 2002 a state tribunal in Puebla finally ordered that the priest be arrested

for the “corruption of minors.” Father Aguilar appealed to a federal judge, who

canceled the arrest warrant because the statute of limitations had expired.

In 2003 Judge Ramírez found Father Aguilar guilty of a lesser charge of touching

the genitals of one boy, but acquitted him of the top charge of corruption of

minors. He sentenced the priest to one year in prison and a $765 fine, according

to court papers.

Father Aguilar was allowed to pay a slightly larger fine to avoid prison and

disappeared once again.

In recent months he has been seen saying Mass in tiny towns in the states of

Puebla and Morelos. The Tehuacán diocese has never defrocked him.

Accused Priest’s Long Flight From Law in U.S. and Mexico, NYT, 21.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/21/world/americas/21mexico.html

Priest Named by Foley Is Barred From All

Religious Duties

October 21, 2006

The New York Times

By ABBY GOODNOUGH

MIAMI, Oct. 20 — The Archdiocese of Miami on

Friday barred the Rev. Anthony Mercieca from functioning as a priest anywhere in

the world after confirming that he was the clergyman who Mark Foley said

molested him in the 1960’s.

Father Mercieca, who now lives in Malta, can no longer publicly celebrate Mass,

administer the sacraments or wear priestly clothes, said Mary Ross Agosta, a

diocesan spokeswoman.

Ms. Agosta apologized to Mr. Foley in a statement and described as repugnant

Father Mercieca’s intimate contact with him, which the priest disclosed to a

Florida newspaper this week. Father Mercieca, 69, worked in South Florida for

almost 40 years and remains under the auspices of the archdiocese.

“Such behavior is morally reprehensible, canonically criminal and inexcusable,”

Ms. Agosta said.

Mr. Foley, 52, resigned from the House of Representatives last month after the

release of sexually explicit messages he had sent to teenage Congressional

pages. Soon after, his lawyer announced that Mr. Foley is gay, had gone into

treatment for alcoholism and had been molested by a clergyman when he was 13 to

15.

“An apology is due to Mr. Foley for the hurt he has experienced,” Ms. Agosta

said.

So far, she said, no one else had reported sexual misconduct by Father Mercieca.

He worked in at least eight parishes in South Florida since 1966, most recently

at Blessed Trinity Catholic Church in Miami Springs from 1993 to 2003. Ms.

Agosta said he left Florida to retire.

“There were absolutely no other problems,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Agosta said the Archdiocese of Miami had begun an internal investigation

that could result in further sanctions against Father Mercieca. A spokesman for

the archbishop of Malta said an investigation was under way there, too.

Though retired, Father Mercieca was still saying Mass every morning at a

cathedral on Gozo, the Maltese island where he was raised and now lives with his

brother, also a priest.

The Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, an advocacy group, said that

both diocesan actions were insufficient and that Father Mercieca should be put

in a secure treatment facility while the police investigated.

The Herald-Tribune of Sarasota, Fla., reported Thursday that Father Mercieca

said he had skinny-dipped and lounged naked in saunas with the young Mr. Foley,

massaged him and roomed with him naked on overnight trips. He said that once, on

tranquilizers, he might have gone further with Mr. Foley but could not recall

details.

Father Mercieca repeated the claims in interviews with other news outlets, but

also said his relationship with Mr. Foley was not sexual.

The survivors group has urged Mr. Foley to press charges, but the statute of

limitations has probably expired. His civil lawyer, Gerald Richman, said Friday

that he had no idea whether Mr. Foley would pursue the matter.

Mr. Richman identified Father Mercieca to Palm Beach County prosecutors this

week as Mr. Foley’s molester. Prosecutors shared the information with the

archdiocese, but said they would do nothing more unless other victims emerged.

Ms. Agosta said the archdiocese, which includes Broward, Miami-Dade and Monroe

Counties, would encourage any other victims to come forward by asking every

parish to make an announcement about Father Mercieca.

Terry Aguayo contributed reporting.

Priest Named by Foley Is Barred From All Religious Duties, NYT, 21.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/21/us/21priest.html

Editorial

Faith-Based Profits

October 16, 2006

The New York Times

Mary Rosati, a novice training to be a nun in

Toledo, Ohio, says that after she received a diagnosis of breast cancer, her

mother superior dismissed her. If Ms. Rosati had had a nonreligious job, she

might have won a lawsuit against her diocese (which denies the charge). But a

federal judge dismissed her suit under the Americans With Disabilities Act,

declining to second-guess the church’s “ecclesiastical decision.”

Ms. Rosati’s story is one of many that Diana Henriques told in a recent Times

series examining the fast-changing legal status of churches and

religious-affiliated institutions. The series showed that the wall between

church and state is being replaced by a platform that raises religious

organizations to a higher legal plane than their secular counterparts.

Day care centers with religious affiliations are exempted in some states from

licensing requirements. Churches can expand in ways that would violate zoning

ordinances if a nonreligious builder did the same thing, and they are permitted,

in some localities, to operate lavish facilities, like state-of-the-art gyms,

without paying property taxes.

Some of the most disturbing stories, like Ms. Rosati’s, involve employment

discrimination. Ms. Henriques told of a New Mexico rabbi who was dismissed after

developing Parkinson’s disease and found himself blocked from suing, and of

nurses in a 44,000-employee health care system operated by the Seventh Day

Adventists barred from joining unions.

Religious institutions should be protected from excessive intrusion by

government. Judges should not tell churches who they have to hire as ministers,

or meddle in doctrinal disputes. But under pressure from politically influential

religious groups, Congress, the White House, and federal and state courts have

expanded this principle beyond all reason. It is increasingly being applied to

people, buildings and programs only tangentially related to religion.

In its expanded form, this principle amounts to an enormous subsidy for

religion, in some cases violating the establishment clause of the First

Amendment. It also undermines core American values, like the right to be free

from job discrimination. It puts secular entrepreneurs at an unfair competitive

disadvantage. And it deprives states and localities of much-needed tax revenues,

putting a heavier burden on ordinary taxpayers.

Like most special-interest handouts, these privileges exist in large part

because the majority is not aware, or is not being heard. With property taxes

growing ever more burdensome, it is likely that localities will start to give

religious exemptions closer scrutiny. People who care about discrimination-free

workplaces, the right to unionize and children’s safety should also start to

push back.

In a few places, at least, that has started. After Texas exempted religious day

care centers and drug-treatment programs from state licensing, a study found

that the “alternatively accredited” facilities had 10 times the rate of abuse

and neglect of the others, and several were investigated. In 2001, the Texas

Legislature, no enemy of organized religion, did the right thing and ended the

exemption.

Faith-Based Profits, NYT, 16.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/16/opinion/16mon1.html

Letter to Priests Is Critical of

Archbishop’s Leadership

October 15, 2006

The New York Times

By MANNY FERNANDEZ

An anonymous letter circulating among priests

in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York is calling for a vote of no

confidence in Cardinal Edward M. Egan, the archbishop of New York.

“During the last six years, the Cardinal’s relations with the Priests of New

York have been defined by dishonesty, deception, disinterest and disregard,”

read the 950-word letter, written by a group calling itself A Committee of

Concerned Clergy for the Archdiocese of New York.

Though it is unclear how many priests are part of the committee, the letter

appears to have resonated with some in the archdiocese. It also is an unusually

public display of internal friction between priests and their archbishop.

In response, Cardinal Egan planned to meet with the Priest Council, the

cardinal’s chief advisory group of about 40 priests, at his residence in

Manhattan tomorrow morning. “He will discuss whatever needs to be discussed with

them,” said Joseph Zwilling, the spokesman for the archdiocese said..

Mr. Zwilling said that Cardinal Egan was taking the letter seriously. “An

anonymous letter of this kind can potentially do great damage to the church,” he

said.

Posted Wednesday on a Catholic news blog called Whispers in the Loggia and

reported on by The New York Daily News on Friday, the letter criticized Cardinal

Egan for ignoring priests’ spiritual concerns, refusing to seek their advice and

fomenting low morale with an arrogant, ruthless manner. The letter said that

committee members must remain anonymous “because of the severely vindictive

nature of Cardinal Egan” and that attempts to “open avenues of communication”

with him had failed.

The letter also claimed that Cardinal Egan’s decision to leave New York two days

after the Sept. 11, 2001, attack is an example of his failure to act as a

spiritual leader in the city. Cardinal Egan, however, did not leave the city in

the days after the attack as claimed in the letter. He visited ground zero,

presided at memorial Masses and spoke at an interfaith service at Yankee Stadium

on Sept. 23. He went to Rome that October to help run a Vatican conference.

Msgr. Howard Calkins, pastor of Sacred Heart Church in Mount Vernon in

Westchester County, said he did not approve of the letter’s harsh tone and

anonymity, but agreed with its description of the morale and communication

problems in the archdiocese. “I think there is truth in it; that the cardinal

has really been an absent figure,” he said.

Monsignor Calkins, who is also vicar of the South Shore Vicariate, said Cardinal

Egan has attempted to reach out to priests in recent years, but that generally

there has been very little consultation with them on the issues affecting the

archdiocese. “I think there’s a feeling that we’re not being heard, even though

he did hold a convocation of the priests of the archdiocese in October 2004,” he

said.

Rocco Palmo, a Philadelphia resident who started the Whispers in the Loggia blog

in 2004, said that a priest who had received the letter called him on Wednesday

and read him the text. After confirming the wording, he said he posted it on his

blog and later received an electronic copy. Mr. Palmo, who is also a

correspondent for The Tablet, a Catholic weekly in London, said he had spoken

with about 40 priests about the letter.

“While nobody is taking credit for this, there’s been little to no critique of

the substance of it,” Mr. Palmo said. “It’s their way of kind of quietly

standing by each other.”

Cardinal Egan was chosen by Pope John Paul II to succeed Cardinal John J.

O’Connor, who died in May 2000. Some priests found Cardinal Egan’s style distant

and clinical. Cardinal O’Connor had extended an open invitation for priests to

visit him at his residence on Wednesdays, without an appointment, to talk about

their concerns. Cardinal Egan did not continue the tradition.

“That I don’t do,” Cardinal Egan said of the practice in an interview with The

New York Times in 2001. “But I assure you this: any priest that calls to see me,

I see.”

The letter stated that a vote of no confidence would encourage Pope Benedict XVI

to accept Cardinal Egan’s resignation in April 2007, when he turns 75. Canon law

requires all bishops to submit a letter to the Pope offering their retirement at

75, Mr. Zwilling said. It is then up to the Pope to accept or postpone

retirement.

“The search for a new Archbishop should begin sooner rather than later,” the

letter stated.

Letter to Priests Is Critical of Archbishop’s Leadership, NYT, 15.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/15/nyregion/15letter.html

Within hours of the start of demolition, not

even debris remained at the site of the Amish school

where a gunman killed five girls and badly wounded five others. The ground will

be returned to pastureland.

Matt Rourke/Associated Press

NYT

Amish

Schoolhouse Is Razed NYT 12.10.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Amish-School-Shooting.html?hp&ex=

1160712000&en=afaeb0d1f7c23ab3&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Amish Schoolhouse Is Razed

October 12, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 11:30 a.m. ET

The New York Times

NICKEL MINES, Pa. (AP) -- Workers with heavy

machinery rather than hand tools moved in before dawn Thursday and demolished

the one-room Amish schoolhouse where a gunman fatally shot five girls and

wounded five others.

Construction lights glared in the mist as a large backhoe tore into the overhang

of the school's porch around 4:45 a.m., then knocked down the bell tower and

toppled the walls. Within 15 minutes, the building was reduced to a pile of

rubble. By 7:30 a.m., the debris was gone, leaving just a bare patch of earth.

The schoolhouse had been boarded up since the killings 10 days earlier, with

classes moved to a nearby farm. The Amish planned to leave a quiet pasture where

the schoolhouse stood.

''I thought there was widespread feeling in the community that it was important

to remove the building,'' said Herman Bontrager, a Mennonite businessman who is

serving as a spokesman. ''Especially for the children, but not only for the

children.''

The Amish are known for constructing buildings by hand, without the aid of

modern technology, but for this job they relied on an outside demolition crew to

bring closure to a painful chapter for their peaceful community.

A group of 20 to 30 people, many of them in traditional Amish dress, gathered

nearby to watch as the schoolhouse was leveled. One Amish man shook his head

when asked if he would comment on the demolition.

''It seems this is a type of closure for them,'' Mike Hart, a spokesman for the

Bart Fire Company, said as loaders lifted debris into dump trucks to be hauled

away.

The destruction of the West Nickel Mines Amish School came a week after the

solemn funerals of the five girls killed by gunman Charles Carl Roberts IV.

Roberts came heavily armed and apparently prepared for a long standoff. He held

the 10 girls hostage for about an hour before shooting them and killing himself

as police closed in.

The five girls wounded in the Oct. 2 shooting are still believed to be

hospitalized. The hospitals are no longer providing any information about the

patients at the request of their families.

Hart, who has been coordinating activities with the Amish community and whose

company will help provide security, said private contractors were handling the

demolition, and the debris would be hauled to a landfill.