|

Vocapedia >

Technology > WWW > Wikipedia

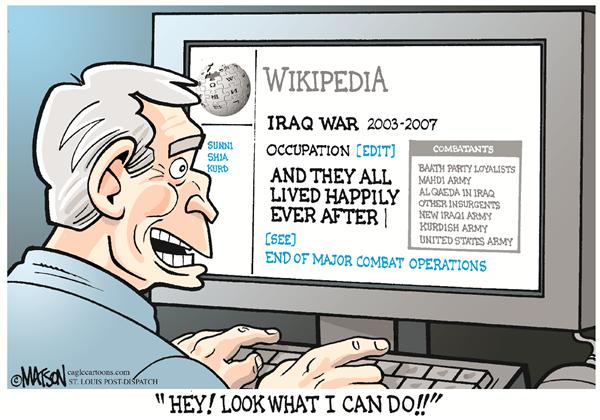

Matson

The St. Louis Post Dispatch

Cagle

22 August 2007

US president George W. Bush

knowledge platform > Wikipedia UK / USA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Main_Page

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/sep/12/

wikipedia-generation-z-young-editors-chatbots

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2023/sep/14/

julian-assange-

more-than-60-australian-mps-urge-us-

to-let-wikileaks-founder-walk-free

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/18/

magazine/wikipedia-ai-chatgpt.html

https://www.npr.org/2022/07/29/

1114599942/wikipedia-recession-edits

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jan/15/

wikipedia-at-20-last-gasp-of-an-internet-vision-or-a-beacon-to-a-better-future

https://www.npr.org/2021/01/04/

953334366/one-page-at-a-time-jess-wade-is-changing-wikipedia

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/02/

in-hysterical-world-wikipedia-ray-of-light-truth

https://www.npr.org/2018/04/27/

606393983/wikipedia-founder-says-internet-users-are-adrift-in-the-fake-news-era

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/04/29/

526184731/turkey-blocks-wikipedia-accusing-it-of-running-smear-campaign

https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/03/20/

520845007/the-earth-is-flat-check-wikipedia

http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/02/22/

515244025/what-students-can-learn-by-writing-for-wikipedia

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/11/

fashion/merriam-webster-dictionary-social-media-politics.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/12/21/

506501985/wikipedia-announces-the-most-edited-articles-of-2016

http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/01/15/

463059593/wikipedia-at-15-the-struggle-to-attract-non-techy-geeks

http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/sep/15/

wikipedia-view-of-the-world-is-still-written-by-the-west

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/

opinion/can-wikipedia-survive.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/10/

opinion/stop-spying-on-wikipedia-users.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/27/

business/media/wikipedia-is-emerging-as-trusted-internet-source-

for-information-on-ebola-.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/10/

technology/wikipedia-vs-the-small-screen.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/opinion/sunday/

wikipedias-sexism-toward-female-novelists.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/interactive/2012/apr/04/

wikipedia-world-language-map

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2012/feb/15/

wikipedia-cairo-educational-initiative

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/06/opinion/steal-this-column.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/18/technology/web-wide-protest-over-two-antipiracy-bills.html

http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/16/wikipedia-plans-to-go-dark-on-wednesday-to-protest-sopa/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2011/feb/19/interview-jimmy-wales-wikipedia

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jan/14/wikipedia-unplanned-miracle-10-years

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/technology/internet/25wikipedia.html

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2006/jun/18/wikipedia.news

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2005/dec/19/digitalmedia.news

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2005/dec/08/wikipedia.news

contributing to Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Wikipedia:About#Contributing_to_Wikipedia

Wikipedia editor UK

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/10/

opinion/stop-spying-on-wikipedia-users.html

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/blog/2009/nov/25/

wikipedia-editors-decline

Wikipedia editor USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/12/21/

506501985/wikipedia-announces-the-most-edited-articles-of-2016

Wikipedians USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/18/

magazine/wikipedia-ai-chatgpt.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/

technology/internet/25wikipedia.html

Wikiproject Medicine

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/27/business/media/

wikipedia-is-emerging-as-trusted-internet-source-for-information-on-ebola-.html

Where Are the Women in Wikipedia? USA

February 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/02/02/

where-are-the-women-in-wikipedia

entry USA

http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/09/

the-backstory-of-wikipedias-take-on-the-iraq-war/

go dark

USA

http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/16/

wikipedia-plans-to-go-dark-on-wednesday-to-protest-sopa/

Jimmy Wales UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/

jimmy-wales

https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2011/feb/19/

interview-jimmy-wales-wikipedia

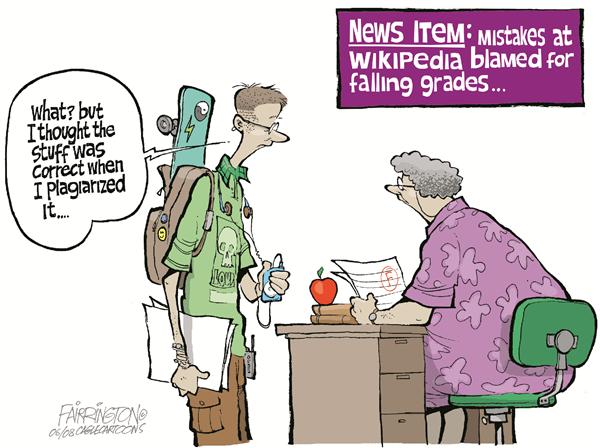

Brian Fairrington

Cagle

23 June 2008

Corpus of news articles

Technology > Internet > Wikipedia

Can Wikipedia Survive?

JUNE 20, 2015

The New York Times

SundayReview | Opinion

By ANDREW LIH

WASHINGTON — WIKIPEDIA has come a long way since it started in

2001. With around 70,000 volunteers editing in over 100 languages, it is by far

the world’s most popular reference site. Its future is also uncertain.

One of the biggest threats it faces is the rise of smartphones as the dominant

personal computing device. A recent Pew Research Center report found that 39 of

the top 50 news sites received more traffic from mobile devices than from

desktop and laptop computers, sales of which have declined for years.

This is a challenge for Wikipedia, which has always depended on contributors

hunched over keyboards searching references, discussing changes and writing

articles using a special markup code. Even before smartphones were widespread,

studies consistently showed that these are daunting tasks for newcomers. “Not

even our youngest and most computer-savvy participants accomplished these tasks

with ease,” a 2009 user test concluded. The difficulty of bringing on new

volunteers has resulted in seven straight years of declining editor

participation.

In 2005, during Wikipedia’s peak years, there were months when more than 60

editors were made administrator — a position with special privileges in editing

the English-language edition. For the past year, it has sometimes struggled to

promote even one per month.

The pool of potential Wikipedia editors could dry up as the number of mobile

users keeps growing; it’s simply too hard to manipulate complex code on a tiny

screen.

The nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation, which oversees Wikipedia’s operations but is

not directly involved in content, is investigating solutions. Some ideas include

touch-screen tools that would let Wikipedia editors sift through information and

share content from their phones.

What has not suffered is fund-raising. The foundation, based in San Francisco,

has a budget of roughly $60 million. How to fairly distribute resources has long

been a topic of debate. How much should go to regional chapters and affiliates,

or to groups devoted to non-English languages? How much should stay in the

foundation to develop software, create mobile apps and maintain infrastructure?

These tensions run through the community. Last year the foundation took the

unprecedented step of forcing the installation of new software on the

German-language Wikipedia. The German editors had shown their independent streak

by resisting an earlier update to the site’s user interface. Against the wishes

of veteran editors, the foundation installed a new way to view multimedia

content and then set up an Orwellian-sounding “superprotect” feature to block

obstinate administrators from changing it back.

The latest clash had repercussions in the election this year for seats to the

Wikimedia Foundation’s board of trustees — the most influential positions that

volunteers can hold. The election — a record 5,000 voters turned out, nearly

three times the number from the previous election — was a rebuke to the status

quo; all three incumbents up for re-election were defeated, replaced by critics

of the superprotect measures. Two other members will leave the 10-member board

at the end of this year. Meanwhile, the foundation’s new executive director,

Lila Tretikov, has been hiring developers from the world of open-source

technology, and their lack of experience with Wikipedia content has concerned

some veterans.

Could the pressure from mobile, and the internal tensions, tear Wikipedia apart?

A world without it seems unimaginable, but consider the fate of other online

communities. Founded in 1985, at the dawn of the Internet, the Well, the

self-proclaimed “birthplace of the online community movement,” hosted an

influential cast of dot-com luminaries on its electronic bulletin board

discussion forums. By 1995, it was in steep decline, and today it is a shell of

its former self. Blogging, celebrated a decade ago as pioneering an exciting new

form of personal writing, has decreased significantly in the social-media age.

These are existential challenges, but they can still be addressed. There is no

other significant alternative to Wikipedia, and good will toward the project — a

remarkable feat of altruism — could hardly be higher. If the foundation needed

more donations, it could surely raise them.

The real challenges for Wikipedia are to resolve the governance disputes — the

tensions among foundation employees, longtime editors trying to protect their

prerogatives, and new volunteers trying to break in — and to design a

mobile-oriented editing environment. One board member, María Sefidari, warned

that “some communities have become so change-resistant and innovation-averse”

that they risk staying “stuck in 2006 while the rest of the Internet is thinking

about 2020 and the next three billion users.”

For the last few years, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and

other world-class institutions, libraries and museums have collaborated with

Wikipedia’s volunteers to improve accuracy, quality of references and depth of

multimedia on article pages. This movement dates from 2010, when the British

Museum saw that Wikipedia’s visitor traffic to articles about its artifacts was

five times greater than that of the museum’s own website. Grasping the power of

Wikipedia to amplify its reach, the museum invited a Wikipedia editor to work

with its curatorial staff. Since then, similar parternships have been set up

with groups like the Cochrane Collaboration, a nonprofit organization that

focuses on evidence-based health care, and the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention.

These are vital opportunities for Wikipedia to tap external expertise and

enlarge its base of editors. It is also the most promising way to solve the

considerable and often-noted gender gap among Wikipedia editors; in 2011, less

than 15 percent were women.

The worst scenario is an end to Wikipedia, not with a bang but with a whimper: a

long, slow decline in participation, accuracy and usefulness that is not quite

dramatic enough to jolt the community into making meaningful reforms.

No effort in history has gotten so much information at so little cost into the

hands of so many — a feat made all the more remarkable by the absence of profit

and owners. In an age of Internet giants, this most selfless of websites is

worth saving.

Andrew Lih is an associate professor of journalism at American University and

the author of “The Wikipedia Revolution: How a Bunch of Nobodies Created the

World’s Greatest Encyclopedia.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up

for the Opinion Today newsletter.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on June 21, 2015, on page SR4 of the

New York edition with the headline: Can Wikipedia Survive?.

Can Wikipedia Survive?,

NYT,

JUNE 20, 2015,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/21/

opinion/ca

Stop Spying on Wikipedia Users

MARCH 10, 2015

The New York Times

The Opinion Pages

Op-Ed Contributors

By JIMMY WALES

and LILA TRETIKOV

SAN FRANCISCO — TODAY, we’re filing a lawsuit against the

National Security Agency to protect the rights of the 500 million people who use

Wikipedia every month. We’re doing so because a fundamental pillar of democracy

is at stake: the free exchange of knowledge and ideas.

Our lawsuit says that the N.S.A.’s mass surveillance of Internet traffic on

American soil — often called “upstream” surveillance — violates the Fourth

Amendment, which protects the right to privacy, as well as the First Amendment,

which protects the freedoms of expression and association. We also argue that

this agency activity exceeds the authority granted by the Foreign Intelligence

Surveillance Act that Congress amended in 2008.

Most people search and read Wikipedia anonymously, since you don’t need an

account to view its tens of millions of articles in hundreds of languages. Every

month, at least 75,000 volunteers in the United States and around the world

contribute their time and passion to writing those articles and keeping the site

going — and growing.

On our servers, run by the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation, those volunteers

discuss their work on everything from Tiananmen Square to gay rights in Uganda.

Many of them prefer to work anonymously, especially those who work on

controversial issues or who live in countries with repressive governments.

These volunteers should be able to do their work without having to worry that

the United States government is monitoring what they read and write.

Unfortunately, their anonymity is far from certain because, using upstream

surveillance, the N.S.A. intercepts and searches virtually all of the

international text-based traffic that flows across the Internet “backbone”

inside the United States. This is the network of fiber-optic cables and

junctions that connect Wikipedia with its global community of readers and

editors.

As a result, whenever someone overseas views or edits a Wikipedia page, it’s

likely that the N.S.A. is tracking that activity — including the content of what

was read or typed, as well as other information that can be linked to the

person’s physical location and possible identity. These activities are sensitive

and private: They can reveal everything from a person’s political and religious

beliefs to sexual orientation and medical conditions.

The notion that the N.S.A. is monitoring Wikipedia’s users is not,

unfortunately, a stretch of the imagination. One of the documents revealed by

the whistle-blower Edward J. Snowden specifically identified Wikipedia as a

target for surveillance, alongside several other major websites like CNN.com,

Gmail and Facebook. The leaked slide from a classified PowerPoint presentation

declared that monitoring these sites could allow N.S.A. analysts to learn

“nearly everything a typical user does on the Internet.”

The harm to Wikimedia and the hundreds of millions of people who visit our

websites is clear: Pervasive surveillance has a chilling effect. It stifles

freedom of expression and the free exchange of knowledge that Wikimedia was

designed to enable.

During the 2011 Arab uprisings, Wikipedia users collaborated to create articles

that helped educate the world about what was happening. Continuing cooperation

between American and Egyptian intelligence services is well established; the

director of Egypt’s main spy agency under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi boasted

in 2013 that he was “in constant contact” with the Central Intelligence Agency.

So imagine, now, a Wikipedia user in Egypt who wants to edit a page about

government opposition or discuss it with fellow editors. If that user knows the

N.S.A. is routinely combing through her contributions to Wikipedia, and possibly

sharing information with her government, she will surely be less likely to add

her knowledge or have that conversation, for fear of reprisal.

And then imagine this decision playing out in the minds of thousands of would-be

contributors in other countries. That represents a loss for everyone who uses

Wikipedia and the Internet — not just fellow editors, but hundreds of millions

of readers in the United States and around the world.

In the lawsuit we’re filing with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union,

we’re joining as a fellow plaintiff a broad coalition of human rights, civil

society, legal, media and information organizations. Their work, like ours,

requires them to engage in sensitive Internet communications with people outside

the United States.

That is why we’re asking the court to order an end to the N.S.A.’s dragnet

surveillance of Internet traffic.

Privacy is an essential right. It makes freedom of expression possible, and

sustains freedom of inquiry and association. It empowers us to read, write and

communicate in confidence, without fear of persecution. Knowledge flourishes

where privacy is protected.

Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, is a board member of the

Wikimedia Foundation, of which Lila Tretikov is the executive director.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on March 10, 2015, on page A21 of the

New York edition with the headline: Stop Spying on Wikipedia Users.

Stop Spying on Wikipedia Users,

NYT,

MARCH 10, 2015,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/10/

opinion/stop-spying-on-wikipedia-users.html

Steal This Column

February 5, 2012

The New York Times

By BILL KELLER

AMONG the wonders of the Internet, Wikipedia occupies a

special place. From its birth 11 years ago it has professed, and has tried

reasonably hard to practice, a kind of idealism that stands out in the vaguely,

artificially countercultural ambience of Silicon Valley. Google’s informal

corporate mantra — “Don’t Be Evil” — has become ever more cringe-making as the

company pursues its world conquest. Though Bill Gates has applied his personal

wealth to noble causes, nobody thinks of Microsoft as anything but a business. I

marvel at Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and his acolytes; but I marvel at their

imagination and industry, not what the new multibillionaire described last week

as their “social mission.” But Wikipedia, while it has grown something of a

bureaucratic exoskeleton, remains at heart the most successful example of the

public-service spirit of the wide-open Web: nonprofit, communitarian,

comparatively transparent, free to use and copy, privacy-minded, neutral and

civil.

Like many people, I was an early doubter that a volunteer-sourced encyclopedia

could be trusted, but I’m a convert. Although I find errors (a spot check of the

entries for myself and my father the other day found minor inaccuracies in both,

which I easily corrected), I use it more than any other Web tool except my

search engines, and because I value it, I donate to its NPR-style fund-raising

campaign.

So as I followed the latest battle in the great sectarian war over the governing

of the Internet — the attempt to curtail online piracy — I was startled to see

that Wikipedia’s founder and philosopher, Jimmy Wales, who generally stays out

of the political limelight, had assumed a higher profile as a combatant for the

tech industry. He supplied an aura of credibility to a libertarian alliance that

ranged from the money-farming Megatrons of Google to the hacker anarchists of

Anonymous.

Et tu, Jimmy?

For those of you who have not followed this subject — or who, like me, regard

phrases like “Net neutrality” as Novocain for the brain — the latest skirmish

concerns the rampant online theft of songs, films, books and other content.

Separate bills advancing in the House and Senate would have given the government

new tools to go after digital bootleggers. The central purpose of the

legislation — rather lost in the rhetorical cross-fire and press coverage — was

to extend the copyright laws that already protect content-creators in the U.S.

to offshore havens where the most egregious pirates have set up shop. Like most

people who make their living the way I do, I think parasite Web sites should be

treated with the same contempt as people who pick pockets or boost cars.

But the legislation in question, drafted by the once-mighty entertainment

industries, was vague and ham-handed, a case of overreach by Hollywood’s

lobbyists. In the journalistic equivalent of taking a bullet for you, I read all

78 staggeringly dull pages of the House version, called SOPA. Interpreted in the

most draconian way, it might have criminalized innocent sites and messed with

the secure plumbing of the Internet itself. The partisans of an unfettered

Internet saw their moment, and seized it. They unleashed a wave of protest that

included much waving of the First Amendment and an attention-grabbing blackout

of Wikipedia, the company’s most conspicuous foray into protest politics. The

legislation is dead, and proponents of the open Web have shown that they are the

new power in Washington.

The question is, how will they use their muscle now? Does this smackdown mean

that any attempt to police the Web for thievery is similarly doomed?

Jimmy Wales, when I connected with him in London, was the voice of reason

compared with some members of the openness alliance. He disavows the hacker

anarchists — whose most recent stunt to protest enforcement of the copyright

laws was to sabotage the Justice Department Web site — as “incredibly

counterproductive.” He said he believes copyright protection is “unquestionably

good” but that enforcement should focus on serious criminal enterprises, not the

music fan who burns a copy for a friend or the search engine that merely offers

the link to a bad place. (Agreed.) He worries that, under too-sweeping

legislation, a site like Wikipedia could be punished because its very

informative article about the aptly named site “The Pirate Bay” includes a link

to the offending destination. (That kind of prosecutorial overkill seems

unlikely, but it would be appalling.)

Wales thinks the current copyright protections — which require publishers,

broadcasters and other content-makers to watch out for piracy of their own

material and notify Internet hosts to take it down — work fine in the U.S. He

grants that enforcement in foreign countries is a problem, but he opposes as

burdensome and stifling any effort to make search engines or other

intermediaries filter what flows through them.

Wales is not endorsing legislation yet, but he had positive things to say about

an alternative bill, one that has won support from some tech companies and

Internet freedom groups. The so-called OPEN Act would give new powers to the

International Trade Commission to issue temporary restraining orders against

sites that specialize in selling bootleg copies of books, movies, TV shows and

so on, and to cut off their access to the online payment processors and

ad-placing services that fund them.

I read those 44 pages, too, and the best that can be said about the law —

drafted by the improbable left-right duo of Senator Ron Wyden, an Oregon

Democrat, and Representative Darrell Issa, a California Republican — is that

it’s a start. An impartial copyright expert who examined the bill at my request

pointed out many loopholes and ambiguities that could make enforcement

cumbersome and easily evaded. And personally, I’d go beyond OPEN (and Jimmy

Wales) to give the intermediaries — search engines, online sharing services —

greater responsibility to police what passes through their sites, rather than

obliging the victim to do all the work.

“Google can remove sites from its search results for causing too much spam; why

not for piracy?” said Robert Levine, whose 2011 book, “Free Ride,” is a

wonderfully clear-eyed account of this colossal struggle over the future of our

cultural lives.

But the OPEN Act is at least something to build on, and its sponsors have

indicated they are flexible. The music and motion-picture industries should be

reaching out to the saner members of the tech industry to collaborate in making

it better, instead of demonizing it as if it were written by Blackbeard himself.

The online industry is not a monolith. Internet companies that have made

fortunes building paid venues — Apple (proprietor of iTunes) and Microsoft (Xbox

Live) and Netflix, among others — have been pretty quiet during the angry

backlash against copyright laws. They have a financial stake in protecting

intellectual property.

“Basically, we need some serious reform,” Wales told me. “Everything should be

on the table. But it’s not a war; it’s a giant public policy question.”

Ah, Jimmy, Jimmy, there’s the rub. These days in Washington, everything is a

war. This is a complicated subject that has been turned into simplistic

sloganeering by rival vested interests dressed up as the saviors of freedom.

When the founders enshrined free speech in the Constitution, they did not mean

“free” in the sense of Wikipedia. As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote in an

important 1985 Supreme Court decision supporting intellectual property rights:

“the Framers intended copyright itself to be the engine of free expression. By

establishing a marketable right to the use of one’s expression, copyright

supplies the economic incentive to create and disseminate ideas.”

Content-makers would be crazy to let the Internet be stunted as a force for

invention, mobilization and shared wisdom. It’s the sea we all swim in.

At the same time, online companies would be crazy to let piracy kill off the

commerce that supplies quality material upon which even free sites like

Wikipedia depend.

Steal This Column, NYT, 5.2.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/06/opinion/steal-this-column.html

Protest on Web Uses Shutdown

to Take On Two Piracy Bills

January 17, 2012

The New York Times

By JENNA WORTHAM

With a Web-wide protest on Wednesday that includes a 24-hour

shutdown of the English-language Wikipedia, the legislative battle over two

Internet piracy bills has reached an extraordinary moment — a political coming

of age for a relatively young and disorganized industry that has largely steered

clear of lobbying and other political games in Washington.

The bills, the Stop Online Piracy Act in the House and the Protect IP Act in the

Senate, are backed by major media companies and are mostly intended to curtail

the illegal downloading and streaming of TV shows and movies online. But the

tech industry fears that, among other things, they will give media companies too

much power to shut down sites that they say are abusing copyrights.

The legislation has jolted technology leaders, venture capitalists and

entrepreneurs, who are not accustomed to having their free-wheeling online world

come under attack.

One response is Wednesday’s protest, which directs anyone visiting Google and

many other Web sites to pages detailing the tech industry’s opposition to the

bills. Wikipedia, run by a nonprofit organization, is going further than most

sites by actually taking material offline — no doubt causing panic among

countless students who have a paper due.

It said the move was meant to spark greater public opposition to the bills,

which could restrict its freedom to publish.

“For the first time, it’s very clear that legislation could have a direct impact

on the industry’s ability to do business,” said Jessica Lawrence, the managing

director of New York Tech Meetup, a trade organization with 20,000 members that

has organized a protest rally in Manhattan on Wednesday. “This has been a

wake-up call.”

Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia Law School, said that the technology industry,

which has birthed large businesses like Google, Facebook and eBay, is much more

powerful than it used to be.

“This is the first real test of the political strength of the Web, and

regardless of how things go, they are no longer a pushover,” said Professor Wu,

who is the author of “The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information

Empires.” He added, “The Web taking a stand against one of the most powerful

lobbyers and seeming to get somewhere is definitely a first.”

Under the proposed legislation, if a copyright holder like Warner Brothers

discovers that a foreign site is focused on offering illegal copies of songs or

movies, it could seek a court order that would require search engines like

Google to remove links to the site and require advertising companies to cut off

payments to it.

Internet companies fear that because the definitions of terms like “search

engine” are so broad in the legislation, Web sites big and small could be

responsible for monitoring all material on their pages for potential violations

— an expensive and complex challenge.

They say they support current law, which requires Web sites with

copyright-infringing content to take it down if copyright holders ask them to,

leaving the rest of the site intact. Google, which owns YouTube and other sites,

received five million requests to remove content or links last year, and it says

it acts in less than six hours if it determines that the request is legitimate.

The major players supporting the legislation, including the United States

Chamber of Commerce and the Motion Picture Association of America, say those

measures are not enough to protect intellectual property. They emphasize that

their primary targets are foreign Web sites that sell counterfeit goods and let

people stream and download music and video at no charge — sites that are now

largely out of reach of United States law enforcement. And they are fighting

against what they characterize as gimmicks and distortions by Internet companies

opposed to the bills.

With talk of censorship and loss of Internet freedom, “the current debate has

nothing to do with the substance of the bills,” David Hirschmann, who leads the

Chamber of Commerce’s initiative on intellectual property, said in an interview.

“We will certainly use every tool in our toolbox to make sure members of

Congress know what’s in these bills.”

With financial resources that few other groups can match, the chamber is one of

Washington’s most powerful lobbying forces and has shown the ability to alter

Congressional debate on its own.

Senator Patrick J. Leahy, Democrat of Vermont and author the Protect IP Act,

accused opponents Tuesday of trying to “stoke fear” through tactics like the

Wikipedia blackout. “Protecting foreign criminals from liability rather than

protecting American copyright holders and intellectual property developers is

irresponsible, will cost American jobs, and is just wrong,” he said in a

statement.

Opponents of the legislation have clearly seized the momentum in the debate.

Their protests have gained traction in that key provisions were stripped out of

one bill and the Obama administration has raised concerns. Legislators have

already agreed to delay or drop one ire-inducing component of the bills, Domain

Name System blocking, which would prevent access to sites that were found to

have illegal content.

A total of 115 companies and organizations have lobbyists working on the

antipiracy bills, spending millions of dollars to sway the outcome, according to

federal disclosure records. They include corporate and technology giants on both

sides of the legislation, with entertainment groups like News Corporation and

the Recording Industry Association of America backing it and Internet firms like

Google and Facebook raising concerns about it.

The largest advocates for the bills disagree with the tech industry’s main

rallying cry, which is the notion that they will hurt the average Internet user

or interfere with their online activities.

“The bill will not harm Wikipedia, domestic blogs or social network sites,” said

Representative Lamar Smith, Republican of Texas and a primary sponsor of the

House bill.

Most people in the tech world agree that the problem of piracy needs to be

addressed. But they say their main concern is that the tech industry had little

influence on the language of the legislation, which is still in flux and so

broadly worded that it is not entirely clear how Internet businesses will be

affected. Big Internet companies say the bills could prevent entire Web sites

from appearing in search results — even if the sites operate legally and most

content creators want their videos or music to appear there.

“It shouldn’t apply to U.S. Web sites, but any company with a server overseas or

a domain name overseas could be at risk,” said Andrew McLaughlin, vice president

at Tumblr, a popular blogging service.

Mr. McLaughlin said the fear is that on large and diverse Web communities like

Tumblr, any user who uploads an unauthorized clip from a movie or an unreleased

track from an album is putting the whole company in the line of fire.

In November, Tumblr rigged a tool that “censored” the page its users see when

they log into the site, explained the legislation and routed them to contact

information for their representatives in Congress. The stunt resulted in 80,000

calls to legislators in a three-day period. Mr. McLaughlin said the company was

planning a similar approach for Wednesday.

Some who oppose the bill, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an

online rights group, see a bright spot in a potential compromise called the OPEN

Act, which would provide for the International Trade Commission to judge cases

of copyright or trademark infringement. If the commission found that a foreign

site was largely devoted to piracy, it could compel payment processors and

online advertising companies to stop doing business with it.

Silicon Valley has championed companies that provide alternatives to piracy,

like Spotify and Netflix. And the industry says that the problem could be solved

by letting it do what it does best — innovating.

“It’s something that could be solved using technology through collaboration with

these start-ups,” said Ms. Lawrence of New York Tech Meetup.

Reporting was contributed by Eric Lichtblau, Edward Wyatt

and

Claire Cain Miller.

Protest on Web Uses Shutdown to Take On Two

Piracy Bills, NYT, 17.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/18/technology/

web-wide-protest-over-two-antipiracy-bills.html

Wikipedia – an unplanned miracle

Every day since its birth 10 years ago,

Wikipedia has got better.

Yet it's

amazing it even exists

Guardian.co.uk

Friday 14 January 2011

22.00 GMT

Clay Shirky

This article was published on guardian.co.uk

at 22.00 GMT on Friday 14 January

2011.

A version appeared on p36

of the Main section section of the Guardian

on

Saturday 15 January 2011.

It was last modified at 00.03 GMT

on Saturday 15 January 2011.

Wikipedia is the most widely used reference work in the world.

That statement is both ordinary and astonishing: it's a simple reflection of its

enormous readership; and yet, by any traditional view about how the world works,

Wikipedia shouldn't even exist, much less have succeeded so dramatically in the

space of a single decade.

The cumulative effort of Wikipedia's millions of contributors means you are a

click away from figuring out what a myocardial infarction is, or the cause of

the Agacher Strip war, or who Spangles Muldoon was. This is an unplanned

miracle, like "the market" deciding how much bread goes in the store. Wikipedia,

though, is even odder than the market: not only is all that material contributed

for free, it is available to you free; even the servers and system

administrators are funded through donations. That it would become such a miracle

was not obvious at its inception and so, on the occasion of its 10th birthday,

it's worth retelling the improbable story of its genesis.

Ten years ago today, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger were stuck trying to create

Nupedia, an online encyclopedia with a seven-step publishing process.

Unfortunately, that also meant seven places where things could grind to a halt.

However, after nearly a year of work, almost no articles had actually been

published.

So, 10 years ago tomorrow, Wales and Sanger decided to try a wiki, as a way of

cutting through some of that process. Sanger sent an email to Nupedia

collaborators about this new way of working, saying: "Humour me. Go there and

add a little article. It will take all of five or ten minutes."

The "Humour me" bit was necessary because the wiki is social media at its most

radical. Invented in the mid-90s by Ward Cunningham, a wiki has at its core only

one technical function: edit. You don't need permission to add, alter, or delete

text, and when you are done, you don't need permission to publish.

More remarkably, though, a wiki also has at its core only one social operation:

I care. The people who edit pages are the ones who care enough to edit them.

Putting the people who care in charge, rather than anointing experts or

authorities, was so radical that Wales and Sanger didn't propose replacing

Nupedia with a wiki. Instead, they proposed using the wiki to generate raw

material for Nupedia.

The participants, however, had other ideas. The ability to create an article in

five minutes, and to make an existing article a little better in less, was so

infectious that in a matter of days there were more articles on the nascent wiki

than on Nupedia. The wiki was so good, and so different from Nupedia, it was

soon moved to its own site. Wikipedia was born. (Nupedia was shut down a few

months later; Sanger also left the project.)

That process continues today, making Wikipedia an ordinary miracle for more than

250 million people a month. Every single day for the last 10 years Wikipedia has

got better because someone – several million someones in all – decided to make

it better. Sometimes that meant starting a new article. Mostly it meant editing

an existing one. Occasionally it meant defending Wikipedia against vandalism.

Always it meant caring. Most participants care a little, editing only one

article. A handful care a lot, contributing hundreds of thousands of edits,

across thousands of articles, over years. Most importantly, taken together, all

of us have contributed enough to make Wikipedia what we have today. What looks

like a stable thing is in fact a result of ceaseless attempts to preserve what

is good, and to improve what isn't. Wikipedia is best understood not as a

product with an organisation behind it, but as an activity that happens to leave

an encyclopedia in its wake.

That shift, from product to activity, has involved the most amazing expansion of

peer review ever: Wikipedia's editor-in-chief is a rotating quorum of whoever is

paying attention. Many of Wikipedia's critics have focused on the fact that the

software lets anyone edit anything; what they miss is that the social

constraints of the committed editors keep that capability in check. As easy as

the software makes it to do damage, it makes it even easier to undo damage.

Imagine a wall where it was easier to remove graffiti than add it: the amount of

graffiti on such a wall would depend on the commitment of its defenders. So with

Wikipedia; if all its passionate participants were to stop caring, the whole

thing would be gone by next Thursday, overrun by vandals and spammers. If you

can see Wikipedia right now, it means that again, today, the good guys won.

Wikipedia isn't perfect, of course. Many mediocre articles need improvement. The

editors are not diverse enough in age, gender or ethnicity. Biographies of the

living remain a persistent site of mischief. Defences erected against vandals

and spammers also see off novices and exhaust old-timers. But Wikipedia isn't

just an activity at the level of the articles; from the individual edits all the

way up to the culture of the whole, Wikipedia is a public good created by the

public, so it falls to the people who care to try to take on these problems as

well. As long as that culture continues to embrace "be bold" as a core value,

its status as one of the largest cumulative acts of generosity in history will

persist. So happy 10th birthday to Wikipedia, and ardent thanks to the millions

of people who have added and altered and argued and amended, the people who have

created the most widely used reference work in the world. Thanks for telling us

the story of the Stonewall riots and how Pluto got demoted to "dwarf planet";

about the Great Rift Valley and the Indian Ocean tsunami; about lion fish and

tiger teams and bear markets. And along with the birthday wishes, here's hoping

enough of us keep caring enough to be able to greet you again, in rude good

health, for your 20th.

Wikipedia – an

unplanned miracle, G, 14.1.2011,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jan/14/

wikipedia-unplanned-miracle-10-years

The wiki-snobs are taking over

Wikipedia is to curb its open-to-all policy

after a string of

howlers,

its boss tells Giles Hattersley

February 8, 2009

The Sunday Times

Jimmy Wales is in the departure lounge at JFK airport, New

York, sucking his breath with shame as he tells me of the moment when his

beloved Wikipedia got it wrong.

“Take your pick,” I’m thinking. Was it the day Alan Titchmarsh’s Wikipedia entry

stated that he had penned a sequel to the Kama Sutra? Or when Bruce

Springsteen’s biography kicked off with: “This guy kinda sucks.” Or when

Alistair Darling’s life story was replaced with a sentence so profane it would

be impossible to reprint here?

“No, it was the Ted Kennedy thing,” sighs Wales. Ah yes. That. Also known as the

day last month when Wikipedia – the world’s largest online encyclopedia,

co-founded by Wales eight years ago – announced that a member of America’s most

scrutinised dynasty had died . . . when, actually, he hadn’t.

It was Wales’s tipping point. Tomorrow the youthful-looking 42-year-old guardian

of wiki-world is putting forward a controversial proposal to ensure that changes

to the most popular wiki-pages are vetted before they go live. The biographies

of living persons and hot topics such as Gaza and God will have to be

scrutinised by arbitrators chosen from Wikipedia’s most active volunteer

contributors. These “core users” are the wiki-devotees who have spent years

posting and editing content. Some have worked on 10,000 pages from their spare

room in Basingstoke or on a laptop in Tokyo – and all for free. As a thank you,

they now get a say in how it’s run.

Sounds innocuous enough? But given that Wikipedia was founded on the principle

that anyone can post, edit, tweak or vandalise it at any time, you have to

wonder whether Wales’s libertarian experiment has failed.

A not atypical tale of how a Wikipedia entry can come into being is the story of

Bertie, then 11, a friend’s son, who was charged to deliver a school report on

Deal castle. He found no reference on Wikipedia, so after researching his essay

the old-fashioned way (books!) he uploaded his report on the site. To be fair,

young Bertie’s is by no means the least scholarly posting on the site. “I think

that’s great,” says Wales, who is big on “access”.

Wales’s enthusiasm aside, there have been sceptics about the open-access model

since the site was launched. Many of the first entries were lifted from the 1911

edition of Encyclopedia Britannica, but most of the content is user generated.

Accordingly, the site often feels like the Mrs Malaprop of cyberspace. You will

no doubt be familiar with the poor spelling, shaky sources and downright

misinformation. With notable exceptions, many of the 10m posts have become a

dodgy crutch for lazy students with an essay due.

Last month the crisis took hold. Wales’s utopian dream of shared knowledge –

built on the idea that none of us is as smart as all of us – seemed to be

unravelling. The headlines stank. Miley Cyrus, Oprah Winfrey and Steve Jobs had

all been declared dead and Margaret Thatcher’s entry claimed she was a

fictitious character. Then the “Kennedy moment” occurred.

“What’s interesting is that I was personally trying to edit the page as it

happened,” says Wales, scratching the designer stubble he has sported since he

quit his job as a high-rolling stocks trader in the 1990s and headed to Florida

to live his internet dream. “I finished watching the inauguration and the

television was still on and there were these early reports that Ted Kennedy had

been whisked away, so I went immediately to Wikipedia to see how things were

looking and I saw that he was dead. I instantly questioned it, because CNN said

they didn’t have all the facts on his condition and I thought it was pretty

unlikely that we would have it before they did.

“I thought: somebody’s jumped the gun here. So I went to edit it out of the page

but it was already being used so I couldn’t get on there.”

He pawed impotently at his keyboard. “It was extremely frustrating. This was a

very high-profile biography on a very high-profile day and it would have been

pretty straightforward to have stopped that.”

But would it? Wikipedia may be open to all, in theory, but it is in effect run

by a cabal of 3,000 amateur know-alls.

“They are an extremely smart, committed group, who seem to work almost full-time

on the project while at work or at home,” marvels Wales, whose paid staff number

a mere 25. “I don’t know how they get anything else done.”

The know-alls squabble constantly over “facts”, undoing each other’s work and

posting their own, but they tend to band together to protect their supremacy if

any upstarts come along. Between them they manage more than 70% of information

on the site. As Wikipedia has featured in the top 10 most visited sites globally

for five years, they have become the de facto arbiters of mankind’s collective

memory. Aside from the practical impossibility of sieving so much information,

doesn’t the site’s gang rule fly in the face of Wales’s hippie-tastic dream of

access for everyone?

“Well, I’m not a hippie,” Wales says. “I’m a centre-right, free-market

capitalist. And, actually, I think the opposite to you. There is a core

community who are extremely powerful but that is a good thing.

One of the great misconceptions about us is this idea that Wikipedia is

anti-elitist. That’s just wrong. We are actually extremely snobby.” And proud of

it? “Yes. These core users really manage and enforce our standards. If it

weren’t for them Wikipedia would be chock full of rubbish.”

Perhaps that should be “more” chock full. When Wikipedia and Britannica were

pitted against one another, the website was found to have 33% more errors. “I’ve

always been concerned about this,” Wales says. “We get this error or that error

making headlines and it’s something I don’t like to see. But at the same time I

feel it’s a bit unwarranted and usually means people don’t understand how

Wikipedia works.”

Or doesn’t work? “Look, if some mistake is only live for five minutes, is it

really cause for thinking of us as completely insane? For one thing, in the old

days with print, correcting an error took a day. We can do it fast.”

But while howlers such as Kennedy’s death are easily spotted, what of the reams

of erroneous detail that the site presents as fact?

My entry features at least two errors, one libellous (unless my mother has been

keeping a dark secret, I am not Roy Hattersley’s son). “Yes, sometimes a person

will post something that is a commonly held error. I say to people that just

because you’ve heard something somewhere does not make it valid.”

Wales claims that the plans to vet will increase accuracy. However, as Wikipedia

gives more power to its vociferous elite, won’t it become just what it never

wanted to be – a wannabe Académie Française?

“Wikipedia is human, evolving and democratic, so it will always be different,”

he says. But will it ever be accurate?

Perhaps not, says Wales: “One of my favourite examples of a mistake was in my

own biography. Someone had edited it to say I relax by playing chess with

friends. I don’t. I’ve nothing against it, I just don’t happen to play chess.

But this stayed on my biography for weeks.” If they can’t get it right for the

guy who runs it, could it be that all of us aren’t smarter than one of us after

all?

The wiki-snobs are

taking over, STs, 8.2.2009,

http://technology.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/

tech_and_web/the_web/article5682896.ece

Wikipedia a force for good?

Nonsense, says a co-founder

April 11,

2007

From The Times

Alexandra Frean,

Education Editor

The founder

of the Wikipedia online encyclopaedia criticised the Education Secretary

yesterday for suggesting that the website could be a good educational tool for

children.

Mr Johnson described the internet as “an incredible force for good in education”

for teachers and pupils, singling out Wikipedia for praise.

“Wikipedia enables anybody to access information which was once the preserve

only of those who could afford the subscription to Encyclopaedia Britannica and

could spend the time necessary to navigate its maze of indexes and content

pages,” he told the annual conference of the National Association of

Schoolteachers and Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT) in Belfast.

But Larry Sanger, who helped to found Wikipedia in 2001, said that the site was

“broken beyond repair” and no longer reliable.

Wikipedia is among the top ten most visited sites on the internet, containing

more than six million articles contributed only by members of the public. But it

has been criticised for being riddled with inaccuracies and nonsense.

Last month it was revealed that a prominent and long-standing Wikipedia

contributor had lied about his identity, having claimed to be a tenured

university professor, when he was in fact a 24-year-old college drop-out.

Concerned about the website’s integrity, Mr Sanger left Wikipedia, and two weeks

ago launched an online encyclopaedia called Citizendium.org, which he said would

be monitored and edited by academics and experts as well as accepting public

contributions.

He told The Times: “I’m afraid that Mr Johnson does not realise the many

problems afflicting Wikipedia, from serious management problems, to an often

dysfunctional community, to frequently unreliable content, and to a whole series

of scandals. While Wikipedia is still quite useful and an amazing phenomenon, I

have come to the view that it is also broken beyond repair.”

Nick Gibb, the Tory schools spokesman, said: “A huge amount of the current

curriculum, particularly in history, is devoted to teaching children to be

discerning when it comes to information on the internet.

“It appears the Secretary of State is not quite as modern as he needs to be in

this information age.”

Mr Johnson also used his speech to call on social networking websites to stop

pupils posting inappropriate videos of and abusive comments about their teachers

on the internet.

In one case a female teacher’s head was superimposed on to a pornographic

photograph.

Mr Johnson said that the online harassment of teachers was causing some to

consider leaving the profession. He called on the providers of websites to take

firmer action to block or remove offensive school material, in the same way that

they have cut pornographic content.

However, Chris Keates, the union’s general secretary, told Mr Johnson that his

call was likely to have little impact.

Wikipedia a force for good? Nonsense, says a co-founder,

Ts, 11.4.2007,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/

tol/life_and_style/education/article1637535.ece -

broken link

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia

technology

|