|

Vocapedia >

Technology > Internet > Personal data

Privacy

Web tracking, Data tracking, Data mining,

Big Data, Data harvesting, Algorithms

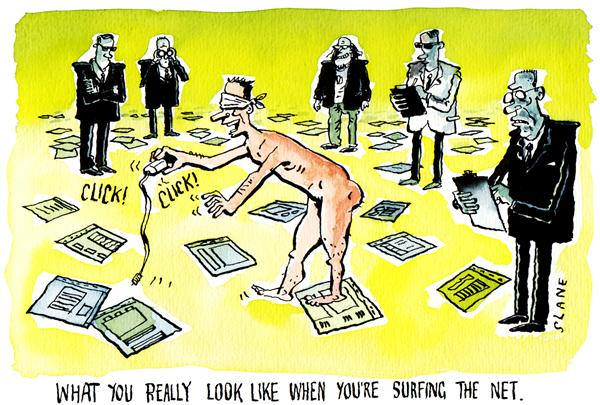

How You Look On The Net

editorial cartoon

By Chris Slane

New Zealand

Cagle

8 February 2005

http://www.politicalcartoons.com/cartoon/

a9f8e9cd-48ed-4eab-b990-eaac7de5b900.html

cookies and web tracking

UK / USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/21/

technology/21cookie.html

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2006/sep/28/

newmedia.business

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2006/sep/28/

newmedia.business

track

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/06/

technology/legislation-would-regulate-tracking-of-cellphone-users.html

track consumers online

without

their knowledge USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/19/

technology/google-to-pay-17-million-to-settle-privacy-case.html

data USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/23/

technology/personaltech/ai-phones-computers-privacy.html

data tracking USA

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/04/

616280585/apple-requested-zero-personal-data-in-deals-with-facebook-ceo-tim-cook-says

data mining USA

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/04/

616280585/apple-requested-zero-personal-data-in-deals-with-facebook-ceo-tim-cook-says

Twitter > illegally using peoples' personal data

(...)

to help sell targeted advertisements.

https://www.npr.org/2022/05/25/

1101275323/twitter-privacy-settlement-doj-ftc

Google > tracking purchases Internet users make in person,

at physical store locations.

USA

https://www.npr.org/2017/07/31/

540610933/watchdog-group-files-complaint-over-google-tracking-in-person-purchases

Google > scan emails in Gmail

accounts

in order sell targeted advertising

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

534451513/google-says-it-will-no-longer-read-users-emails-to-sell-targeted-ads

tracker USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/09/26/

495502526/online-trackers-follow-our-digital-shadow-by-fingerprinting-browsers-devices

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/

technology/ftc-moves-to-tighten-online-privacy-protections-for-children.html

Tracking the trackers:

who are the companies monitoring us

online? - interactive April 23, 2012

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/interactive/2012/apr/23/

tracking-trackers-companies-following-online - broken link

collect information on users

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/24/us/

politics/facebook-ads-politics.html

collect information about the online

activities

of millions of young Internet users

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/

technology/ftc-moves-to-tighten-online-privacy-protections-for-children.html

collect, collate and

analyze information

about a wide range

of

consumer activities and traits USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/

technology/ftc-moves-to-tighten-online-privacy-protections-for-children.html

online behaviour UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/05/

algorithms-rate-credit-scores-finances-data

mine personal details and online

behavior USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

personal information

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

detailed personal information

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/21/

opinion/sunday/facebook-patents-privacy.html

individual ratings UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/05/

algorithms-rate-credit-scores-finances-data

algorithms UK

https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=FXdYSQ6nu-M -

G - 17 March 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/05/

algorithms-rate-credit-scores-finances-data

big data UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/05/

algorithms-rate-credit-scores-finances-data

big data USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/09/09/

492297006/how-will-big-data-change-the-way-we-live

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/11/28/

503035862/big-data-coming-in-faster-than-biomedical-researchers-can-process-it

http://www.npr.org/2016/09/12/

493654950/weapons-of-math-destruction-outlines-dangers-of-relying-on-data-analytics

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/08/06/

is-big-data-spreading-inequality

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/02/us/

white-house-report-calls-for-transparency-in-online-data-collection.html

collect

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

gather

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/07/17/

629441555/health-insurers-are-vacuuming-up-details-about-you-and-it-could-raise-your-rates

data-gathering practices

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/

technology/ftc-moves-to-tighten-online-privacy-protections-for-children.html

data garb UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/feb/28/

google-summoned-data-grab-excesses

data dealers USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/

business/on-the-data-sharing-trail-try-following-the-breadcrumbs.html

data sellers

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/25/

technology/congress-opens-inquiry-into-data-brokers.html

data brokers

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/02/

opinion/facebook-silicon-valley-regulation.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/08/06/

is-big-data-spreading-inequality

harvest user data

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

google-russia-rutarget-sberbank-sanctions-ukraine - July 1, 2022

data harvesting

USA

https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=FXdYSQ6nu-M -

G - 17 March 2018

data harvesting

USA

Google’s harvesting

of e-mails, passwords

and other sensitive personal

information

from unsuspecting households

in the United States and around the world

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/

technology/google-engineer-told-others-of-data-collection-fcc-report-reveals.html

data privacy vault

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/09/

business/company-envisions-vaults-for-personal-data.html

Privacy and the Apps You Download

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/12/11/

privacy-and-the-apps-you-download

violate

the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act

USA

http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/11/

new-concerns-over-apps-for-children/

The Center for Digital Democracy

and Common Sense Media

have partnered for a campaign

to support

the Federal Trade Commission's

proposed rule changes to update

the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

for the digital

era. USA

https://www.democraticmedia.org/

Mapping, and Sharing, the Consumer

Genome USA

2012

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/

technology/acxiom-the-quiet-giant-of-consumer-database-marketing.html

charting consumers' buying power

USA 2012

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/19/

business/electronic-scores-rank-consumers-by-potential-value.html

Rubicon Project

Ever wonder why

that same ad for

a car or a couch

keeps popping up on your screen?

Nearly always,

the answer is real-time bidding,

an electronic trading system

that sells ad space

on the Web pages people visit

at the very moment

they are

visiting them.

Think of these systems

as a sort of Nasdaq stock market,

only trading in audiences

for online ads.

Millions of bids

flood in every second.

And those bids

— essentially what your eyeballs

are worth to advertisers —

could determine whether you see an ad for,

say, a new Lexus or a used Ford,

for sneakers or a popcorn maker.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/18/

technology/your-online-attention-bought-in-an-instant-by-advertisers.html

profile

profiling spending,

Web browsing

and social media habits USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/

business/on-the-data-sharing-trail-try-following-the-breadcrumbs.html

compile psychological profiles of millions of web

users UK

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2007/may/12/

newmedia.news

privacy / personal data

UK / USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2018/05/28/

614419275/do-not-sell-my-personal-information-california-eyes-data-privacy-measure

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/19/

technology/with-graph-search-facebook-bets-on-more-sharing.html

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2012/oct/16/

google-privacy-policies-eu-data-protection

privacy advocates

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/04/

1003205422/states-fight-over-how-our-data-is-tracked-and-sold-online-as-congress-stalls

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/

technology/google-engineer-told-others-of-data-collection-fcc-report-reveals.html

Deleting your online presence

-

share your experiences 25 March 2013

UK

Your online profile

can be an increasingly useful tool

in controlling your

image,

but what if you wanted

to delete the 'online' you

and start over again?

Help the Guardian news team

investigate profile deletion processes

https://www.theguardian.com/news/blog/2013/mar/25/

delete-your-online-presence

Secure Sockets Layer SSL

That cryptography system,

called

SSL for short

and used by many online

banking and e-commerce sites,

protects people who log in to sites

over an open Wi-Fi network

— like the kind offered

by many coffee shops —

from strangers who might be using

snooping software on the same network.

(An “https” at the beginning of a URL

indicates SSL encryption.)

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/23/

business/data-security-is-a-classroom-worry-too.html

policing > data

analysis USA

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/25/

622715984/how-data-analysis-is-driving-policing

Corpus of news articles

Technology > Internet > Personal data >

Privacy

Their Apps Track You.

Will Congress Track Them?

January 5, 2013

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

WASHINGTON

THERE are three things that matter in consumer data collection: location,

location, location.

E-ZPasses clock the routes we drive. Metro passes register the subway stations

we enter. A.T.M.’s record where and when we get cash. Not to mention the credit

and debit card transactions that map our trajectories in comprehensive detail —

the stores, restaurants and gas stations we frequent; the hotels and health

clubs we patronize.

Each of these represents a kind of knowing trade, a conscious consumer

submission to surveillance for the sake of convenience.

But now legislators, regulators, advocacy groups and marketers are squaring off

over newer technology: smartphones and mobile apps that can continuously record

and share people’s precise movements. At issue is whether consumers are

unwittingly acquiescing to pervasive tracking just for the sake of having mobile

amenities like calendar, game or weather apps.

For Senator Al Franken, the Minnesota Democrat, the potential hazard is that by

compiling location patterns over time, companies could create an intimate

portrait of a person’s familial and professional associations, political and

religious beliefs, even health status. To give consumers some say in the

surveillance, Mr. Franken has been working on a locational privacy protection

bill that would require entities like app developers to obtain explicit one-time

consent from users before recording the locations of their mobile devices. It

would prohibit stalking apps — programs that allow one person to track another

person’s whereabouts surreptitiously.

The bill, approved last month by the Senate Judiciary Committee, would also

require mobile services to disclose the names of the advertising networks or

other third parties with which they share consumers’ locations.

“Someone who has this information doesn’t just know where you live,” Mr. Franken

said during the Judiciary Committee meeting. “They know the roads you take to

work, where you drop your kids off at school, the church you attend and the

doctors that you visit.”

Yet many marketers say they need to know consumers’ precise locations so they

can show relevant mobile ads or coupons at the very moment a person is in or

near a store. Informing such users about each and every ad network or analytics

company that tracks their locations could hinder that hyperlocal marketing, they

say, because it could require a new consent notice to appear every time someone

opened an app.

“Consumers would revolt if this was the case, and applications could be rendered

useless,” said Senator Charles Grassley, the Iowa Republican, who promulgated

industry arguments during the committee meeting. “Worse yet, free applications

that rely on advertising could be pushed by the consent requirement to become

fee-based.”

Mr. Franken’s bill may seem intended simply to protect consumer privacy. But the

underlying issue is the future of consumer data property rights — the question

of who actually owns the information generated by a person who uses a digital

device and whether using that property without explicit authorization

constitutes trespassing.

In common law, a property intrusion is known as “trespass to chattels.” The

Supreme Court invoked the legal concept last January in United States v. Jones,

in which it ruled that the government had violated the Fourth Amendment — which

protects people against unreasonable search and seizure — by placing a GPS

tracking device on a suspect’s car for 28 days without getting a warrant.

Some advocacy groups view location tracking by mobile apps and ad networks as a

parallel, warrantless commercial intrusion. To these groups, Mr. Franken’s bill

suggests that consumers may eventually gain some rights over their own digital

footprints.

“People don’t think about how they broadcast their locations all the time when

they carry their phones. The law is just starting to catch up and think about

how to treat this,” says Marcia Hofmann, a senior staff lawyer at the Electronic

Frontier Foundation, a digital rights group based in San Francisco. “In an ideal

world, users would be able to share the information they want and not share the

information they don’t want and have more control over how it is used.”

Even some marketers agree.

One is Scout Advertising, a location-based mobile ad service that promises to

help advertisers pinpoint the whereabouts of potential customers within 100

meters. The service, previously known as ThinkNear and recently acquired by

Telenav, a personalized navigation service, works by determining a person’s

location; figuring out whether that place is a home or a store, a health club or

a sports stadium; analyzing weather and other local conditions; and then showing

a mobile ad tailored to the situation.

Eli Portnoy, general manager of Scout Advertising, calls the technique

“situational targeting.” He says Crunch, the fitness center chain, used the

service to show mobile ads to people within three miles of a Crunch gym on rainy

mornings. The ad said: “Seven-day pass. Run on a treadmill, not in the rain.”

When a person clicks on one of these ads, Mr. Portnoy says, a browser-based map

pops up with turn-by-turn directions to the nearest location. Through GPS

tracking, Scout Advertising can tell when someone starts driving and whether

that person arrives at the site.

Despite the tracking, Mr. Portnoy describes his company’s mobile ads as

protective of privacy because the service works only with sites or apps that

obtain consent to use people’s locations. Scout Advertising, he adds, does not

compile data on individuals’ whereabouts over time.

Still, he says, if Congress were to enact Mr. Franken’s location privacy bill as

written, it “would be a little challenging” for the industry to carry out,

because of the number and variety of companies involved in mobile marketing.

“We are in favor of more privacy,” Mr. Portnoy says, “but it has to be done

within the nuances of how mobile advertising works so it can scale.”

A SPOKESMAN for Mr. Franken said the senator planned to reintroduce the bill in

the new Congress. It is one of several continuing government efforts to develop

some baseline consumer data rights.

“New technology may provide increased convenience or security at the expense of

privacy and many people may find the trade-off worthwhile,” Justice Samuel Alito

wrote last year in his opinion in the Jones case. “On the other hand,” he added,

“concern about new intrusions on privacy may spur the enactment of legislation

to protect against these intrusions.”

Their Apps Track You. Will Congress Track

Them?,

NYT,

5.1.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/06/

technology/legislation-would-regulate-tracking-of-cellphone-users.html

A Vault for Taking Charge

of Your Online Life

December 8, 2012

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

REDWOOD CITY, Calif.

“YOU are walking around naked on the Internet and you need some clothes,” says

Michael Fertik. “I am going to sell you some.”

Naked? Not exactly, but close.

Mr. Fertik, 34, is the chief executive of Reputation.com, a company that helps

people manage their online reputations. From his perch here in Silicon Valley,

he views the digital screens in our lives, the smartphones and the tablets, the

desktops and the laptops, as windows of a house. People go about their lives on

the inside, he says, while dozens of marketing and analytics companies watch

through the windows, sizing them up like peeping Toms.

By now many Americans are learning that they are living in a surveillance

economy. “Information resellers,” also known as “data brokers,” have collected

hundreds to thousands of details — what we buy, our race or ethnicity, our

finances and health concerns, our Web activities and social networks — on almost

every American adult. Other companies that specialize in ranking consumers use

computer algorithms to covertly score Internet users, identifying some as

“high-value” consumers worthy of receiving pitches for premium credit cards and

other offers, while dismissing others as a waste of time and marketing money.

Yet another type of company, called an ad-trading platform, profiles Internet

users and auctions off online access to them to marketers in a practice called

“real-time bidding.”

As these practices have come to light, several members of Congress, and federal

agencies, have opened investigations.

At least for now, however, these companies typically do not permit consumers to

see the records or marketing scores that have been compiled about them. And that

is perfectly legal.

Now, Mr. Fertik, the loquacious, lion-maned founder of Reputation.com, says he

has the free-market solution. He calls it a “data vault,” or “a bank for other

people’s data.”

Here at Reputation.com’s headquarters, a vast open-plan office decorated with

industrial-looking metal struts and reclaimed wood — a discreet homage to the

lab where Thomas Edison invented the light bulb — his company has amassed a

database on millions of consumers. Mr. Fertik plans to use it to sell people on

the idea of taking control of their own marketing profiles. To succeed, he will

have to persuade people that they must take charge of their digital personas.

Pointing out the potential hazards posed by data brokers and the like is part of

Mr. Fertik’s M.O. Covert online profiling and scoring, he says, may unfairly

exclude certain Internet users from marketing offers that could affect their

financial, educational or health opportunities — a practice Mr. Fertik calls

“Weblining.” He plans to market Reputation.com’s data vault, scheduled to open

for business early next year, as an antidote.

“A data privacy vault,” he says, “is a way to control yourself as a person.”

Reputation.com is at the forefront of a nascent industry called “personal

identity management.” The company’s business model for its vault service

involves collecting data about consumers’ marketing preferences and giving them

the option to share the information on a limited basis with certain companies in

exchange for coupons, say, or status upgrades. In turn, participating companies

will get access both to potential customers who welcome their pitches and to

details about the exact products and services those people are seeking. In

theory, the data vault would earn money as a kind of authorization supervisor,

managing the permissions that marketers would need to access information about

Reputation.com’s clients.

To some, the idea seems a bit quixotic.

Reputation.com, with $67 million in venture capital, is not making a profit.

Although the company’s “privacy” products, like removing clients’ personal

information from list broker and marketing databases, are popular, its

reputation management techniques can be controversial. For instance, it offers

services meant to make negative commentary about individual or corporate clients

less visible on the Web.

And there are other hurdles, like competition. A few companies, like Personal,

have already introduced vault services. Also, a number of other enterprises have

tried — and quickly failed — to sell consumers on data lockers.

Even so, Mr. Fertik contends Reputation.com has the answer. The company already

has several hundred thousand paying customers, he says, and patents on software

that can identify consumers’ information online and score their reputations. He

intends to show clients their scores and advise them on how to improve them.

“You can’t just build a vault and wish that vendors cared enough about your data

to pay for it,” Mr. Fertik says. “You have to build a business that gives you

the lift to accumulate a data set and attract consumers, the science to create

insights that are valuable to vendors, and the power to impose restrictions on

the companies who consume your data.”

THE consumer data trade is large and largely unregulated.

Companies and organizations in the United States spend more than $2 billion a

year on third-party data about individuals, according to a report last year on

personal identity management from Forrester Research, a market research firm.

They spend billions more on credit data, market research and customer data

analytics, the report said.

Unlike consumer reporting agencies, which compile credit reports, however,

business-to-business companies that calculate consumer valuation scores, or

collect and sell consumer marketing data, are not required by federal law to

show people the records the companies have about them or allow them to correct

errors in their own files.

Marketing industry groups argue that regulation is unnecessary. They say Web

sites have privacy policies to explain what data they and their business

partners collect. They add that third-party data collectors do not know Internet

users’ real names and compile consumers’ online marketing records under customer

code numbers. Besides, they say, Internet users who are uncomfortable with

seeing ads based on data-mining about themselves may use an industry group’s

program, Your Ad Choices, to opt out of receiving customized pitches.

As the popular conversation shifts from practices like privacy policies and

opt-outs to ideas like consumer empowerment and data rights, however, marketing

industry efforts have not kept pace with changing public attitudes, analysts

say.

“Consumers are leaving an exponentially growing digital footprint across

channels and media, and they are awakening to the fact that marketers use this

data for financial gain,” Fatemeh Khatibloo, an analyst at Forrester, wrote in

the report. “This, combined with growing concerns about data security, means

that individuals increasingly want to know when data about them is being

collected, what is being stored and by whom, and how that data is being used.”

A variety of industries could respond by providing services that offer consumers

greater control, she wrote. These might include online companies like Yahoo,

Microsoft and Google that already house certain categories of data for

consumers; social networks like Facebook and LinkedIn; data vaults like

Personal, which allow consumers to store and manage certain kinds of data; and

companies like Reputation.com whose business model already relies on customers

willing to pay for data privacy.

In a phone interview last month, Ms. Khatibloo described how such an ecosystem

might work.

Consumers could choose a variety of companies or institutions to house and

manage different categories of their information. They might select a financial

institution as the gatekeeper for their financial data, a medical center to

manage their health data, and a consumer data locker as their retail manager.

Then, when a person is ready to buy a car, she could authorize her personal

vault to share relevant financial and insurance information with a car dealer.

Or a person might allow his home insurer to survey his retail data vault for

purchases every month and automatically increase his insurance coverage if he

buys expensive items like a home entertainment system, she said.

“What is necessary to make that happen,” Ms. Khatibloo said, is “an inflection

point of consumers adopting technology that makes it more valuable for marketers

to come to them directly for their data.”

Marketers and information resellers will also have to acknowledge that consumers

have some rights to information collected about them, she said. If the industry

does not update its data capture practices, legislators and regulators are

likely to mandate public data access, she said.

With increasing complaints by consumer advocacy groups and investigations by the

news media, the surveillance economy is attracting greater government scrutiny.

Two separate efforts in Congress are now examining practices by third-party

consumer data collectors. Regulators at the Federal Trade Commission and

researchers at the Government Accountability Office are also investigating. In a

report this year, the F.T.C. recommended that Congress pass a law giving

consumers the right to have some access to the records data brokers compile

about them.

“We have a right, I think, to all of the data we have a hand in generating,” Ms.

Khatibloo said. “I have the right to know who is tracking me online, who is

looking at my behavior as I move from site to site, what data they are

collecting, all of these.”

MR. FERTIK, blue marker in hand, sketches his vision of a data vault on a white

board in a conference room at Reputation.com’s headquarters. “The problem is you

don’t own your data,” he says. “Now, imagine owning your data.”

He sketches a silo and labeles it “data privacy vault.” To the left of the silo,

he draws an arrow saying “IN: data about people.” To the right of the vault, he

draws another arrow which says “OUT: data to vendors.”

It is a system he has previously described at the World Economic Forum in Davos,

Switzerland; at Harvard Law School; at the Aspen Institute. He points to the

diagram.

“This is the future. Let me demystify it. This is not difficult technology,” he

says. “It’s a database where you put your data, or we put it for you, and there

are some rules as to how it is externalized or shared.”

Mr. Fertik’s thinking on consumer privacy developed in part from what he called

his Upper West Side, civil rights, “Jewish, lefty, pinko” upbringing and his

Dalton, Horace Mann, Harvard College, Harvard Law School education. The result,

Reputation.com, founded in 2006, is a part social justice, part profit motive.

“I thought something was wrong,” Mr. Fertik says. “You know when you go into a

bank or an insurer that you may get offered different rates than the next

person, but you have no idea when you go on the Internet that your options, the

offers you get or whether you get a coupon, have been defined 20 steps before

you get to a site.”

For $99 per year, clients can have the company remove their personal details

from databases maintained by various information resellers. They can also

install company software that blocks Web tracking by 200 data brokers,

advertising networks and ad trading platforms. For $5,000 a year, Reputation.com

also offers a “white glove” service for executives who want their personal

details removed from list brokers with more cumbersome opt-out processes.

Reputation’s forthcoming data vault service is just a more elaborate attempt to

monetize consumer privacy.

Mr. Fertik says he doesn’t think it will be difficult to persuade people to

store their data in the vault and share some of it with selected companies in

exchange for benefits like cash, coupons or status upgrades. The companies that

get permission to gain access to his clients’ records, he adds, will have to

sign contracts agreeing not to sell or share them with third parties.

Still, some people may not be comfortable with the fact that Reputation.com has

already amassed files on millions of Americans mainly by scraping the Web. Other

people may wonder whether a consumer data vault is truly secure. Mr. Fertik says

Reputation.com will never share or sell clients’ information without their

permission.

Convincing marketers that Reputation.com’s vault has more valuable information

and consumer insights than an ordinary data broker is another challenge. “In

order to make our information attractive to Best Buy, Amazon or Disney World,

we’d have to tell them we have 5 percent more information about you and better

insights than other sources,” Mr. Fertik says.

EXECUTIVES in technology, retail, marketing and other industries like to say

that data is “the new oil” or, at least, the fuel that powers the Internet

economy. It is a metaphor that casts consumers as natural resources with no say

over the valuable commodities that companies extract from them.

Data vaults could give consumers more control over who sees certain kinds of

information about them and how that information is used.

It is already a common practice in health care. Patients of the Kaiser

Permanente system, for example, can use an online health manager to handle

information about their health care, prescriptions and insurance. Elderly

parents might also choose to give access to their health vault to offspring who

help manage their care.

Still, consumers may not care enough about data-mining by marketers and

information resellers to patronize data vaults. And legislators may eventually

require information resellers to periodically provide consumers with free data

reports, Ms. Khatibloo, of Forrester, said. That would put a dent in the

fee-for-service data vault business.

In fact, some politicians and regulators already argue that services that charge

people to control their personal data are not an appropriate solution to

comprehensive online data collection.

“Having to pay a fee in order to engage in a retrospective effort to claw back

personal information doesn’t seem to us the right way to go about this,” David

Vladeck, the director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the Federal Trade

Commission, said at a Congressional hearing in 2010.

Regulators are moving to give consumers more control over data without having to

pay for it. In February, for example, the White House assigned the Commerce

Department to supervise the development of a “Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights,”

a code of conduct to be worked out between industry and consumer advocacy

groups.

While governmental efforts inch along, companies like Reputation.com are forging

ahead with new services that promise consumers more insight into the data

collected about them. This month, for example, the direct-to-consumer division

of Equifax, the credit information services company, plans to begin offering its

customers a separate personal data report from Reputation.com in addition to

their credit report. Some Equifax customers will also be offered the option to

have Reputation.com delete personal details, like home addresses and phone

numbers, from certain information broker databases.

“We see broadening consumers’ understanding of what’s out there about them

online as a very natural extension of what we do today,” said Trey Loughran, the

president of Equifax Personal Information Solutions.

Next spring, TransUnion Interactive, the consumer division of the TransUnion

credit information company, plans to offer its customers similar services from

Reputation.com.

These deals in no way signify that data vaults are a sure thing or, if they are,

that Reputation.com is the company to take them to the masses. But the sudden

interest from corporations like Equifax and TransUnion gives credence to the

idea that consumers increasingly want to see data collected about themselves and

that there is some commercial benefit in showing it to them.

After all, Mr. Fertik says, “it’s your data.”

A Vault for Taking Charge of Your Online

Life, NYT, 8.12.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/09/business/

company-envisions-vaults-for-personal-data.html

U.S. Is

Tightening Web Privacy Rule

to Shield Young

September

27, 2012

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

Federal

regulators are about to take the biggest steps in more than a decade to protect

children online.

The moves come at a time when major corporations, app developers and data miners

appear to be collecting information about the online activities of millions of

young Internet users without their parents’ awareness, children’s advocates say.

Some sites and apps have also collected details like children’s photographs or

locations of mobile devices; the concern is that the information could be used

to identify or locate individual children.

These data-gathering practices are legal. But the development has so alarmed

officials at the Federal Trade Commission that the agency is moving to overhaul

rules that many experts say have not kept pace with the explosive growth of the

Web and innovations like mobile apps. New rules are expected within weeks.

“Today, almost every child has a computer in his pocket and it’s that much

harder for parents to monitor what their kids are doing online, who they are

interacting with, and what information they are sharing,” says Mary K. Engle,

associate director of the advertising practices division at the F.T.C. “The

concern is that a lot of this may be going on without anybody’s knowledge.”

The proposed changes could greatly increase the need for children’s sites to

obtain parental permission for some practices that are now popular — like using

cookies to track users’ activities around the Web over time. Marketers argue

that the rule should not be changed so extensively, lest it cause companies to

reduce their offerings for children.

“Do we need a broad, wholesale change of the law?” says Mike Zaneis, the general

counsel for the Interactive Advertising Bureau, an industry association. “The

answer is no. It is working very well.”

The current federal rule, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998,

requires operators of children’s Web sites to obtain parental consent before

they collect personal information like phone numbers or physical addresses from

children under 13. But rapid advances in technology have overtaken the rules,

privacy advocates say.

Today, many brand-name companies and analytics firms collect, collate and

analyze information about a wide range of consumer activities and traits. Some

of those techniques could put children at risk, advocates say.

Under the F.T.C.’s proposals, some current online practices, like getting

children under 13 to submit photos of themselves, would require parental

consent.

Children who visit McDonald’s HappyMeal.com, for instance, can “get in the

picture with Ronald McDonald” by uploading photos of themselves and combining

them with images of the clown. Children may also “star in a music video” on the

site by uploading photos or webcam images and having it graft their faces onto

dancing cartoon bodies.

But according to children’s advocates, McDonald’s stored these images in

directories that were publicly available. Anyone with an Internet connection

could check out hundreds of photos of young children, a few of whom were

pictured in pajamas in their bedrooms, advocates said.

In a related complaint to the F.T.C. last month, a coalition of advocacy groups

accused McDonald’s and four other corporations of violating the 1998 law by

collecting e-mail addresses without parental consent. HappyMeal.com, the

complaint noted, invites children to share their creations on the site by

providing the first names and e-mail addresses of their friends.

“When we tell parents about this they are appalled, because basically what it’s

doing is going around the parents’ back and taking advantage of kids’ naïveté,”

says Jennifer Harris, the director of marketing initiatives at the Yale Rudd

Center for Food Policy and Obesity, a member of the coalition that filed the

complaint. “It’s a very unfair and deceptive practice that we don’t think

companies should be allowed to do.”

Danya Proud, a spokeswoman for McDonald’s, said in an e-mail that the company

placed a “high importance” on protecting privacy, including children’s online

privacy. She said that McDonald’s had blocked public access to several

directories on the site.

Last year, the F.T.C. filed a complaint against W3 Innovations, a developer of

popular iPhone and iPod Touch apps like Emily’s Dress Up, which invited children

to design outfits and e-mail their comments to a blog. The agency said that the

apps violated the children’s privacy rule by collecting the e-mail addresses of

tens of thousands of children without their parents’ permission and encouraging

those children to post personal information publicly. The company later settled

the case, agreeing to pay a penalty of $50,000 and delete personal data it had

collected about children.

It is often difficult to know what kind of data is being collected and shared.

Industry trade groups say marketers do not knowingly track young children for

advertising purposes. But a study last year of 54 Web sites popular with

children, including Disney.go.com and Nick.com, found that many used tracking

technologies extensively.

“I was surprised to find that pretty much all of the same technologies used to

track adults are being used on kids’ Web sites,” said Richard M. Smith, an

Internet security expert in Boston who conducted the study at the request of the

Center for Digital Democracy, an advocacy group.

Using a software program called Ghostery, which detects and identifies tracking

entities on Web sites, a New York Times reporter recently identified seven

trackers on Nick.com — including Quantcast, an analytics company that, according

to its own marketing material, helps Web sites “segment out specific audiences

you want to sell” to advertisers.

Ghostery found 13 trackers on a Disney game page for kids, including

AudienceScience, an analytics company that, according to that company’s site,

“pioneered the concept of targeting and audience-based marketing.”

David Bittler, a spokesman for Nickelodeon, which runs Nick.com, says Viacom,

the parent company, does not show targeted ads on Nick.com or other company

sites for children under 13. But the sites and their analytics partners may

collect data anonymously about users for purposes like improving content. Zenia

Mucha, a spokeswoman for Disney, said the company does not show targeted ads to

children and requires its ad partners to do the same.

Another popular children’s site, Webkinz, says openly that its advertising

partners may aim at visitors with ads based on the collection of “anonymous

data.” In its privacy policy, Webkinz describes the practice as “online advanced

targeting.”

If the F.T.C. carries out its proposed changes, children’s Web sites would be

required to obtain parents’ permission before tracking children around the Web

for advertising purposes, even with anonymous customer codes.

Some parents say they are trying to teach their children basic online

self-defense. “We don’t give out birth dates to get the free stuff,” said

Patricia Tay-Weiss, a mother of two young children in Venice, Calif., who runs

foreign language classes for elementary school students. “We are teaching our

kids to ask, ‘What is the company getting from you and what are they going to do

with that information?’ ”

U.S. Is Tightening Web Privacy Rule to Shield Young, NYT, 27.9.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/technology/

ftc-moves-to-tighten-online-privacy-protections-for-children.html

Facebook’s Prospects

May Rest on Trove of Data

May 14, 2012

The New York Times

By SOMINI SENGUPTA

SAN FRANCISCO — Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief, has managed

to amass more information about more people than anyone else in history.

Now what?

As Facebook turns to Wall Street in the biggest public offering ever by an

Internet company, it faces a new, unenviable test: how to keep growing and

enriching its hungry new shareholders.

The answer lies in what Facebook will be able to do — and how quickly — with its

crown jewel: its status as an online directory for a good chunk of the human

race, with the names, photos, tastes and desires of nearly a billion people.

Facebook’s shares are expected to begin trading as early as this week. Already,

lots of investors are scrambling to buy those shares, with giddy hopes that it

will become a big moneymaker like Google. Because of that high demand, Facebook

is expected to increase its offering price from its initial range, giving the

company a valuation possibly as high as $104 billion.

In the eight years since it sprang out of a Harvard dorm room, Facebook has

signed up users at breakneck speed, kept them glued to the site for longer

stretches of time and turned a profit by using their personal information to

customize the ads they see.

Whether it can spin that data into enough gold to justify a valuation of as much

as $104 billion remains unclear.

“We know Facebook has an awful lot of data, but what they have not worked out

yet is the most effective means of using that data for advertising,” said

Catherine Tucker, a professor of marketing at the Sloan School of Management at

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “They are going to have to experiment

a lot more.”

Analysts, investors and company executives can rattle off any number of

challenges facing the company. As it works to better match ads to people, it has

to avoid violating its users’ perceived sense of privacy or inviting regulatory

scrutiny. It needs to find other ways to generate revenue, like allowing people

to buy more goods and services with Facebook Credits, a kind of virtual

currency. Most urgently it has to make money on mobile devices, the window to

Facebook for more and more people.

All the while, its ability to innovate with new features and approaches — to

“break things,” in the words of Mr. Zuckerberg — may be markedly constrained

once it has investors to answer to.

“They are going to have to think about whether they can continue with the motto

‘Done is better than perfect,’ ” said Susan Etlinger, an industry analyst at the

Altimeter Group. “When you’re operating as a public company, life is very

different. We haven’t seen that play out yet. It’s going to take a few quarters

to figure out what a public Facebook is going to look like.”

Skeptics point out that the company’s revenue growth showed signs of slowing in

the first quarter of 2012. And a Bloomberg survey of 1,253 investors, analysts

and traders found that a substantial majority were dubious about the eye-popping

valuation Facebook was seeking. “It’s a risky asset. No doubt about that,” said

Brian Wieser, of Pivotal Research Group. “Google was less risky.” No matter. Mr.

Wieser says he thinks that Facebook is worth $83 billion and that its revenue

will grow by at least 30 percent for the next five years.

The comparisons to Google are inevitable. When that company went public in 2004,

there were so many doubters that the company lowered its offering price to $85 a

share. It closed at just over $100 on the first day of trading, and now sells

for more than $600. Facebook is farther along than Google was in terms of

revenue, having brought in nearly $4 billion last year, or $5.11 a user,

compared with Google’s $2 billion in 2003.

One Facebook investor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of market

regulations as the offering draws near, noted that when Google went public it

already had a clear business strategy. By contrast, he described Facebook this

way: “They have built an incredibly valuable asset — as opposed to a business

they have executed well.”

The most pressing issue for Facebook executives may be the mobile challenge.

Already, over half of Facebook’s 901 million users access the site through

mobile devices. In regulatory filings, the company says mobile use is growing

fastest in some of Facebook’s largest markets, including the United States,

India and Brazil. Facebook goes on to acknowledge that it makes little to no

money on mobile and that “our ability to do so successfully is unproven.”

There is not much space on mobile screens to show advertisements. And Google and

Apple, two of Facebook’s biggest rivals, control the basic software on most

smartphones, which could make it harder for the company to make inroads there.

Facebook’s response to this challenge so far has been to aggressively acquire

companies focused on mobile, including Instagram, for which it paid $1 billion

in April. But it warned in a revision to its offering documents last week that

the mobile shift meant it was adding users faster than it was increasing the

number of ads it displayed.

What Facebook already has — more than any other digital company — is a

spectacularly rich vault of information about its users, who cannot seem to stay

away from the site. Americans, on average, now spend 20 percent of their online

time on Facebook alone, thanks to the ever-growing menu of activities the

company has introduced, from playing games to sampling music to posting pictures

of baby showers and drunken escapades. Some 300 million photos are uploaded to

the site daily.

How Facebook exploits its users’ information — and how those users react — is

the next reckoning. David Eastman, worldwide digital director for the

advertising agency JWT, said Facebook would need to give marketers more data

about what kinds of users click on what kinds of advertising, and about their

travels on the Internet before and after they click on an ad. Most brands want

to have a presence on Facebook, he said, but they do not quite understand who

sees their pitches and whether they lead to greater sales.

“They need to make the data work more,” Mr. Eastman said. “They need to provide

deeper data. Right now the value of Facebook advertising is largely unknown.”

While the bulk of Facebook’s revenue comes from North America, it is banking on

international growth. The company has expanded its global footprint so rapidly

that four out of five Facebook users are now outside the United States. It is

the dominant social network in large emerging markets like Brazil and India,

though it shows no signs of penetrating China — where it would face not only

government censorship but stiff competition from homegrown social networks.

Mr. Zuckerberg, who has studied Mandarin, signaled his ambitions to crack the

vast Chinese market as far back as 2010. He suggested that Facebook would first

try to advance deeper into markets like Russia and Japan before it took on a

country as “complex” as China.

With international growth comes international regulatory headaches. Facebook

already faces audits in Europe on whether the company is living up to promises

made to consumers about how it uses their data — and now, a stringent new data

protection law. In India, it has been sued for spreading offensive content. And

in the United States, it faces privacy audits by the Federal Trade Commission

for the next 20 years. In its offering documents, Facebook repeatedly warns of

legislative and regulatory scrutiny over user privacy, “which may adversely

affect our reputation and brand.”

Maintaining brand loyalty is excruciatingly difficult in the Internet business.

Across Silicon Valley, investors are plotting the next big thing in social

networks. Already, the clock may be ticking for Facebook.

“There is no consumer-facing Internet brand or site that ever keeps consumers’

attention for more than 10 years,” said Tim Chang, a managing director at

Mayfield Fund. “It is not hard to imagine that in 10 years, people are going to

be off of Facebook even.”

Mr. Zuckerberg has an answer to that. In the video for investors released this

month, Mr. Zuckerberg hinted at the ambitions he had for the company. Facebook,

in his vision, will hook itself into the rest of the Web, making itself

indispensable. Already Facebook serves as a de facto Internet passport, allowing

users to log in with their Facebook identities and explore millions of other Web

sites and applications.

“I think that we’re going to reach this point where almost every app that you

use is going to be integrated with Facebook in some way,” Mr. Zuckerberg says in

the video. “We make decisions at Facebook not optimizing for what is going to

happen in the next year, but what’s going to set us up for this world where

every product experience you have is social, and that’s all powered by

Facebook.”

Facebook’s Prospects May Rest on Trove of

Data, NYT, 14.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/15/technology/

facebook-needs-to-turn-data-trove-into-investor-gold.html

Following the Breadcrumbs

on the Data-Sharing Trail

April 28, 2012

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

WOULD you like to donate to the Obama campaign? Sign up for a

college course? Or maybe subscribe to Architectural Digest?

If you have ever felt inundated by such solicitations, by e-mail or by snail

mail, you may have wondered what you did to deserve it.

I did.

I wondered how all those campaigns, companies and institutions got my number.

And how much money data brokers behind the scenes might make by flipping my name

and address.

Turns out there’s no easy way for consumers in the United States to track the

data dealers who profile our spending, Web browsing and social media habits, the

better to sell us stuff. Although the Federal Trade Commission issued a consumer

privacy report last month urging companies that collect and share customer

information to give people more notification and control over the proliferation

of their personal details, the recommendations don’t have the force of binding

regulations.

So, without a right to compel vendors to show me where my data goes, I decided

to do some profiling of my own.

I subscribed to a half-dozen print magazines last year, signing up for each with

a different typo in my name or variation in my address. Then I collected the

direct mail that resulted, tracking the solicitations back to the publishers who

had shared my erroneous contact information.

Admittedly, it was unscientific. But I figured this little off-line experiment

might provide insight into an even more opaque world — online behavioral

targeting — where ad networks deliver tailored marketing pitches to people based

on their location, search queries, online purchases and the like.

Here are the results:

Natawsha, the name under which I had subscribed to Wired and The New Yorker, got

hit up for a donation to Literacy Partners, a tutoring company in Manhattan, and

received a bulletin from the New-York Historical Society.

Nafasha, who signed up for Fast Company, received solicitations from Forbes. The

mangled address I had submitted to Foreign Policy received a cascade of mail

from, among others, the World Monuments Fund, Barron’s and the Kiplinger Letter.

And a subscription to The New York Review of Books led to solicitations from the

Central Park Conservancy, the New York Public Library and The New York Times —

and, on behalf of President Obama’s 2012 campaign, an appeal from Michelle

Obama.

“It is revenue-producing for a publisher to collect subscribers’ information and

sell it,” said Paul Stephens, the director of policy and advocacy at the Privacy

Rights Clearinghouse, a consumer group in San Diego. “It’s just information that

is very valuable to advertisers who want to target individuals based on their

interests.”*

INDEED, the Direct Marketing Association, a trade group, has

estimated that spending on direct marketing in the United States reached $163

billion in 2011.

Still, a report earlier this year from the White House, laying out a privacy

bill of rights for consumers, implicates the decades-old practice of

list-sharing, among others. The report says consumers have a right to expect

that companies will collect, use and share information in ways consistent with

the context in which people provided it.

In other words, if you subscribe to a magazine, you might reasonably expect to

receive offers from magazines owned by the same publishing house, said Nancy J.

King, a privacy law expert who is an associate professor at Oregon State

University’s College of Business.

“But you probably would not have expected a magazine to share your information

with a political campaign” that has inferred your political preferences from

your choice of periodicals, Professor King said.

Of course, publishers are hardly the only businesses sharing and selling

consumer information. In the United States, with the exception of specific

sectors like credit and health care, companies are free to use their customers’

data as they deem appropriate. That means every time a person buys a car or a

house, takes a trip or stays in a hotel, signs up for a catalog or shops online

or in a mall, his or her name might end up on a list shared with other

marketers. That can happen directly, or through middlemen known as list brokers

and data brokers.

The ultimate purpose of all this sharing and profiling is to personalize

marketing, using analytics to predict the offers most likely to interest

consumers based on their past behavior, says Linda A. Woolley, the executive

vice president of Washington operations at the Direct Marketing Association.

“Sometimes the analytics are right; sometimes they are wrong,” Ms. Woolley said.

“The industry exists to try to perfect those guesses.”

For those who’d rather not receive such offers, she said, the trade group offers

a dedicated Web site, dmachoice.org, where people can opt out of getting all

kinds of direct mail or specific categories of it, like credit card offers.

But Christopher Olsen, the assistant director of privacy and identity protection

in the Federal Trade Commission’s bureau of consumer protection, said companies

ought to notify their customers if they plan to share information about them

with third parties — rather than simply permitting people to opt out after the

fact. Indeed, the agency’s recent report calls on industry to be more

transparent with consumers.

“If your name is flying around the ether because you have subscribed to a

magazine,” Mr. Olsen said, “you ought to understand who has got that information

and whether you have a choice about its onward distribution.”

ALTHOUGH all of the magazines contacted for this article said

their subscribers could opt out, some publishers took a more active approach

than others to notifying readers of their practices.

Natalie Raabe, a spokeswoman for The Atlantic, for example, said the magazine

occasionally allows companies it has screened to contact subscribers about

products or services that may be of interest. But the magazine does not share

subscriber addresses directly with these companies, she said; it uses a third

party to administer the process.

A spokeswoman for Condé Nast, publisher of The New Yorker, said it adhered to

industry best practices and offered subscribers multiple ways to opt out.

Diane R. Seltzer, list manager at The New York Review of Books, vets all

proposals from companies that want to market to subscribers to ensure the offers

are appropriate. Those making the cut are charged a rental fee of $105 per 1,000

names for one-time use, she said. The publication runs an ad in every issue, she

added, notifying subscribers of this practice and explaining how to opt out.

“We are very proactive in trying to keep subscribers happy,” she said.

In light of the new federal privacy reports, however, at least one publisher

said it might halt, or at least further limit, the selling of its subscriber

list.

“I think media companies are going to have to tackle this issue,” said David

Rothkopf, the new chief executive of Foreign Policy. Two months into the job, he

said, he had hired a new circulation director and intended to review his

magazines’ list-sharing policy: “I think there are people out there who don’t

want to be part of some giant circulating mailing list.”

Following the Breadcrumbs on the

Data-Sharing Trail, NYT, 28.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/business/

on-the-data-sharing-trail-try-following-the-breadcrumbs.html

Data Harvesting at Google

Not a Rogue Act, Report Finds

April 28, 2012

The New York Times

By DAVID STREITFELD

SAN FRANCISCO — Google’s harvesting of e-mails, passwords and

other sensitive personal information from unsuspecting households in the United

States and around the world was neither a mistake nor the work of a rogue

engineer, as the company long maintained, but a program that supervisors knew

about, according to new details from the full text of a regulatory report.

The report, prepared by the Federal Communications Commission after a 17-month

investigation of Google’s Street View project, was released, heavily redacted,

two weeks ago. Although it found that Google had not violated any laws, the

agency said Google had obstructed the inquiry and fined the company $25,000.

On Saturday, Google released a version of the report with only employees’ names

redacted.

The full version draws a portrait of a company where an engineer can easily

embark on a project to gather personal e-mails and Web searches of potentially

hundreds of millions of people as part of his or her unscheduled work time, and

where privacy concerns are shrugged off.

The so-called payload data was secretly collected between 2007 and 2010 as part

of Street View, a project to photograph streetscapes over much of the civilized

world. When the program was being designed, the report says, it included the

following “to do” item: “Discuss privacy considerations with Product Counsel.”

“That never occurred,” the report says.

Google says the data collection was legal. But when regulators asked to see what

had been collected, Google refused, the report says, saying it might break

privacy and wiretapping laws if it shared the material.

A Google spokeswoman said Saturday that the company had much stricter privacy

controls than it used to, in part because of the Street View controversy. She

expressed the hope that with the release of the full report, “we can now put

this matter behind us.”

Ever since information about the secret data collection first began to emerge

two years ago, Google has portrayed it as the mistakes of an unauthorized

engineer operating on his own and stressed that the data was never used in any

Google product.

The report, quoting the engineer’s original proposal, gives a somewhat different

impression. The data, the engineer wrote, would “be analyzed offline for use in

other initiatives.” Google says this was never done.

The report, which was first published in its unredacted form by The Los Angeles

Times, also states that the engineer, who began the project as part of his “20

percent” time that Google gives employees to do work on their own initiative,

“specifically told two engineers working on the project, including a senior

manager, about collecting payload data.”

As early as 2007, the report says, Street View engineers had “wide access” to

the plan to collect payload data. Five engineers tested the Street View code, a

sixth reviewed it line by line, and a seventh also worked on it, the report

says.

Privacy advocates said the full report put Google in a bad light.

“Google’s rogue engineer scenario collapses in light of the fact that others

were aware of the project and did not object,” said Marc Rotenberg, executive

director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center. “This is what happens in

the absence of enforcement and the absence of regulation.”

The Street View program used special cars outfitted with cameras. Google first

said it was just photographing streets and did not disclose that it was

collecting Internet communications called payload data, transmitted over Wi-Fi

networks, until May 2010, when it was confronted by German regulators.

Eventually, it was forced to reveal that the information it had collected could

include the full text of e-mails, sites visited and other data.

Even if a user was not working on a computer at the moment the Street View car

slowly passed, if the device was on and the network was unencrypted, all sorts

of information about what the user had been doing could be scooped up, data

experts say.

“So how did this happen? Quite simply, it was a mistake,” a Google executive

wrote on a company blog in 2010. “The project leaders did not want, and had no

intention of using, payload data.”

But according to the report, the engineer suggested in his proposal that it was

entirely intentional: “We are logging user traffic along with sufficient data to

precisely triangulate their position at a given time, along with information

about what they were doing.”

Attending to paperwork did not seem to be a high priority, however. Managers of

the Street View project told F.C.C. investigators that they never read the

engineer’s proposal, called a design document. A senior manager of Street View

said he “preapproved” the document before it was written.

More than a dozen countries began investigations of Street View in 2010. In the

United States, the Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, state

attorneys general and the F.C.C. looked into the matter.

The engineer at the center of the project cited the Fifth Amendment protection

against self-incrimination. Because F.C.C. investigators could not interview

him, they said there were still unresolved questions about the case.

Data Harvesting at Google Not a Rogue Act,

Report Finds,

NYT,

28.4.2012,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/

technology/google-engineer-told-others-of-data-collection-

fcc-report-reveals.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

technology

|