|

Vocapedia > Media > USA > NYT > Illustrations >

2008-2009

Gerry Greaney

Op-Ed Contributor

Bright Lights, Big

Internet

July 30, 2009

The New York Times

By BILL WASIK

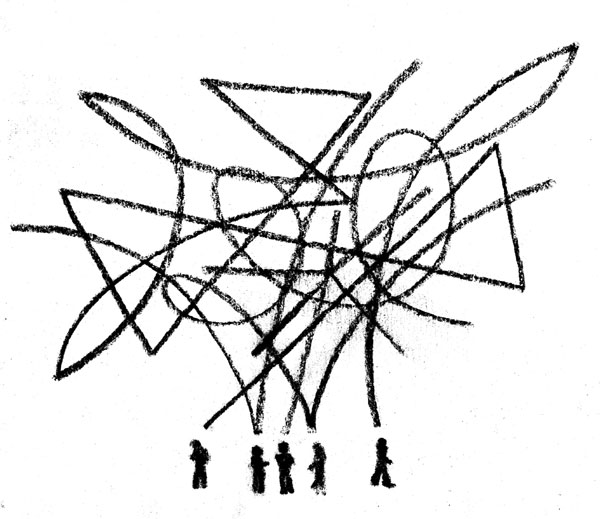

THIS summer, as in so many summers gone by, young aspirants to

the creative class — would-be writers, musicians, artists, editors, comedians,

performers, thinkers, provocateurs — are stepping off buses in Port Authority

and trains in Penn Station, navigating their rented trucks and borrowed cars

through outer-borough blocks. These new arrivals come to New York, first and

foremost, to find one another, a flock of other young people like themselves.

But they come also to seek success, to chase their “big break,” that vague but

real moment when, as if by magic, one suddenly finds oneself on the opposite

side of the glass from one’s nose print.

Is New York still worth the trip? Recessions tend to be hard on youthful dreams,

but this downturn has proved especially dispiriting. Those in the print media

have come to see their present fiscal woes as not merely cyclical but

structural, and so their slashed workforce and diminished output seem unlikely

to rebound any time soon. Galleries have closed. Foundations, their endowments

devastated, have cut back on grants for the arts. Internships across the board

are down by more than 20 percent. And those of us who still hold full-time jobs

in creative fields are clinging to them for dear life, making it difficult for

young people to pry any free for themselves.

Meanwhile, another destination beckons, a place that courses with all the raw

ambition and creative energy that the hard times seem to have drained from New

York. I am referring, of course, to the Internet, which over the past decade has

slowly become the de facto heart of American culture: the public space in which

our most influential conversations transpire, in which our new celebrities are

discovered and touted, in which fans are won and careers made.

Wherever young creatives physically reside today, in their endeavors they are

increasingly moving online: posting their photos, writing, videos and music,

building a “presence” in the hope of winning an audience. Monetary rewards on

the Internet are still scarce, it is true, but the cost of living is cheap and,

more important, the opportunities for attention are plentiful. Every month more

YouTube sensations emerge, more bloggers ink big book deals, more bands blow up

through music Web sites and MySpace, and every day more young people seek their

“big break” in the virtual megalopolis rather than in (or as well as in) the

physical one.

The experience of moving online actually bears quite a few similarities to

becoming a New Yorker. Disorienting and seemingly endless, the Internet

conversation moves at lightning speed and according to unstated social rules

that can bewilder outsiders. Also, like New Yorkers, residents of the Internet

do not suffer fools, or mince words in belittling them, as anyone who has

contributed a redundant post to Metafilter, or an earnest comment to Gawker, can

attest.

In their scope, both the Internet and New York are profoundly humbling: young

people accustomed to feeling special about their gifts are inevitably jarred,

upon arrival, to discover just how many others are trying to do precisely the

same, with equal or greater success. (For a vivid demonstration of this online,

try to invent a play on words, and then Google it. You’ll be convinced that

there is, in fact, “nothing new in the cloud” — a joke that a British I.B.M.

employee beat me to last November.)

Moreover, the presence of an audience causes online residents to style

themselves as outsized personae, as characters on a public stage. On the

Internet, as in creative New York, everyone can possess a tiny measure of

celebrity, and everyone pays attention to what everyone else is doing, all the

time.

Six months after my own arrival in this city, when I began a brief stint in 2000

working in the Condé Nast building, I was surprised to see minor incidents from

the elevators, or the cafeteria, appear in the pages of The New York Observer,

just as a decade before they might have shown up in Spy magazine. Today, of

course, that sort of mirthful over-scrutiny is everyone’s lot, as any

misdirected e-mail message in any city or industry whatsoever is likely to find

its way onto blogs and into the public domain.

But online, when creative affirmation finally arrives, it takes a very different

form than it has in New York. In the offline world, getting a “big break” is a

matter of impressing a subjective intelligence, one person or a few people who

look at work with an experienced eye and declare there’s something to it. Up

until now, it has been intimate encouragement that has literally set the course

of whole careers: a gallery offers a show, a record label dangles a contract, a

prospective boss plucks one résumé from a sheaf, and a path forward is set.

Such moments of recognition, by individuals or small groups, have helped to

decide not merely who succeeds but at what. A nice note from a famous poet can

cause an amorphously creative young person to throw the novels and screenplays

overboard and take up verse for life. Without intervention from The New Yorker,

John Updike might well have been a cartoonist, James Thurber a journalist,

William Shawn himself a composer.

On the Internet, however, it’s not one single subjectivity but a popular

hive-mind that decides. The “big break” arrives when, with lightning speed and

often to one’s own surprise, the inscrutable pack decides to start forwarding

one’s content around.

Like the note from the poet, the viral blowup online is transformative: The

Gregory Brothers, transplants to Brooklyn from Radford, Va., are a serious soul

band, but ever since the sudden success, this spring, of their deliriously funny

YouTube series “Auto-Tune the News” (which turns news footage of politicians and

pundits into pop jams), they’ve been devoting ever more time to keeping their

hundreds of thousands of online fans entertained. Talk to anyone who makes

culture online and you’ll often hear a similar story — of the first Web site

that took off, or the video or the new meme successfully disseminated.

And so the move online changes how we make art, but the road ahead there is

uncharted and perilous. In the old model, young creatives dreamed of

entertaining the millions, but in practice they could do so only by first

pleasing a small group of gatekeepers: established figures who controlled access

to the audience and, in doing so, protected young people from that audience, its

obsessions and desertions, its adoration and its scorn. These old hands had to

worry about the numbers, of course, but they rationalized the upticks and

downticks through a certain set of professional values, which they themselves

spent years imbibing and which they in turn pressed upon their wards.

Online, though, the audience can be yours right away, direct and unmediated — if

you can figure out how to find it and, what’s harder, to keep it. What to you is

a big break is, to this increasingly sophisticated and fickle audience, just one

forwarded e-mail message in a teeming inbox, to be refilled again tomorrow with

a whole new slate of distractions. “Microcelebrity” is now the rule, with

respect not only to the size of one’s fan base but also to the duration of its

love. Believe it or not, the Internet is a tougher town than New York; fewer

people make it here, but no one there seems to make it for long.

Bill Wasik, a senior editor at Harper’s, is the author

of “And

Then There’s This:

How Stories Live and Die in Viral Culture.”

Bright Lights, Big

Internet, NYT, 30.7.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/opinion/30wasik.html

|