|

Vocapedia >

Economy > Currencies

> Euro

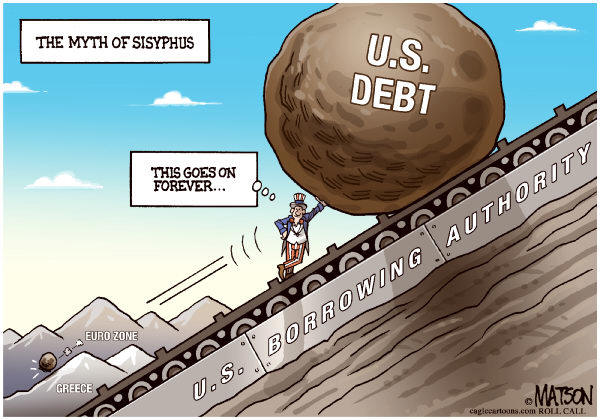

RJ Matson

Roll Call

Cagle

21 June 2011

single currency

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/14/

euro-single-currency-greece

currency > euro

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

euro

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/22/

three-days-to-save-the-euro-greece

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/26/

opinion/sunday/how-the-euro-turned-into-a-trap.html

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/03/

greece-referendum-euro-destroying-european-dream-deficit-fetishists

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/12/

business/alexandre-lamfalussy-a-euro-founder-dies-at-86.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/12/

business/international/delight-or-dread-as-euro-falls.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/09/

opinion/the-stumbling-tumbling-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/15/

opinion/krugman-the-money-trap.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/02/

opinion/sunday/douthat-prisoners-of-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/30/

opinion/krugman-crash-of-the-bumblebee.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/14/

euro-single-currency-greece

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jan/25/

davos-soros-roubini-warnings-eurozone

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/17/

business/global/euro-woes-could-revive-bout-of-market-volatility.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/29/

euro-sinks-italian-bond-auction

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/28/

euro-low-dollar-banks-ecb

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/

business/global/european-leaders-agree-on-fiscal-treaty.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/09/

euro-currency-live-discussion

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/audio/2011/dec/09/

politics-weekly-podcast-europe-cameron-treaty

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/02/

angela-merkel-action-euro-collapse

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/

opinion/krugman-killing-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/

opinion/the-fed-and-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/17/

business/daily-stock-market-activity.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/16/

business/global/european-economy-grew-0-2-percent-in-3rd-quarter-

helped-by-france-and-germany.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/world/europe/

for-european-union-and-the-euro-a-moment-of-truth.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/20/world/europe/

euro-meant-to-unite-europe-seems-to-be-dividing-it.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/21/

business/global/21schioppa.html

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2010/05/17/

business/business-us-markets-global.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/15/

opinion/15krugman.html

take

Britain into the euro

euro > Maastricht treaty UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/09/

euro-currency-live-discussion

Europe USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/29/

opinion/paul-krugman-the-fall-of-france.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/12/01/

europes-identity-crisis

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/

opinion/sunday/kristof-why-is-europe-a-dirty-word.html

European Central Bank ECB

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/

european-central-bank

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/16/

uk-banks-greek-euro-exit

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/29/

euro-sinks-italian-bond-auction

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/28/

euro-low-dollar-banks-ecb

euro zone’s jobless rate

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/02/business/global/

unemployment-in-euro-zone-rose-to-new-high-in-august.html

euro woes USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/17/business/global/

euro-woes-could-revive-bout-of-market-volatility.html

'euromess'

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/15/

opinion/15krugman.html

euro collapse

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/02/

angela-merkel-action-euro-collapse

on edge of financial collapse

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/14/

greece-on-edge-financial-collapse

economic crash

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/21/world/europe/

amid-the-echoes-of-an-economic-crash-the-sounds-of-greek-society-being-torn.html

Eurozone GDP > double-dip recession

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/nov/15/

eurozone-double-dip-recession

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/datablog/interactive/2012/nov/15/

eurozone-falls-back-into-recession

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/nov/15/

eurozone-recession-economists

economy > European debt crisis / eurozone crisis

2011-2015

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/debt-crisis

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/e/

european_sovereign_debt_crisis/index.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/

business/international/greece-debt-crisis-euro.html

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/22/

three-days-to-save-the-euro-greece

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jul/06/

greek-referendum-optimism-fades-eurozone-yanis-varoufakis

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/

opinion/paul-krugman-ending-greeces-bleeding.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/world/europe/

with-no-greek-vote-tsipras-wins-a-victory-that-could-carry-a-steep-price.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/18/

opinion/europes-recurring-malaise.html

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/31/

european-union-dream-austerity-disharmony

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/15/

opinion/krugman-the-money-trap.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/09/

opinion/greece-drinks-the-hemlock.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/

spain-eurozone-impending-doom

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/

spain-eu-rescue-funds-borrowing-costs

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/14/

greece-on-edge-financial-collapse

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/25/

opinion/the-euro-crisis-this-time.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/23/

eurozone-crisis-france-germany-divide

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/21/world/europe/

greek-crisis-poses-hard-choices-for-western-leaders.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/global/2012/may/16/

cost-greek-exit-euro-emerges

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/16/

business/economy/leaving-the-euro-may-be-better-than-the-alternative.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/14/euro-single-currency-greece

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/07/eurozone-crisis-merkel-athens-paris

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/business/global/sp-cuts-its-rating-on-spain-citing-debt.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/reality-check-with-polly-curtis/2012/apr/25/economicgrowth-debt-crisis

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/16/opinion/krugman-europes-economic-suicide.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/feb/15/greece-forced-out-eurozone-venizelos

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/world/europe/eu-leaders-fall-short-of-far-reaching-debt-solution.html

http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/u-s-banks-tally-their-exposure-to-europes-debt-maelstrom/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jan/25/davos-soros-roubini-warnings-eurozone

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/17/

business/global/euro-woes-could-revive-bout-of-market-volatility.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/03/business/global/

ramon-fernandez-french-point-man-keeps-out-of-the-limelight.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/17/business/global/

angry-salvos-on-euro-pact-sail-across-the-channel.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/16/french-ministers-britain-economy-bigger

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/15/imf-world-risks-1930s-style-slump

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/15/france-eurozone-row-uk-credit-downgrade

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/14/eu-treaty-cameron-sarkozy-row

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/opinion/europes-latest-try.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/business/global/european-leaders-agree-on-fiscal-treaty.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/dec/09/cameron-eu-treaty-veto-analysis

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/dec/09/michael-white-blog-splendid-isolation

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/09/uk-leading-role-europe-hague

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/09/clegg-cameron-veto-eu-summit

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/gallery/2011/dec/09/national-leaders-eu-summit-pictures

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/dec/09/labour-condemns-cameron-eu-veto

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/09/euro-currency-live-discussion

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/audio/2011/dec/09/politics-weekly-podcast-europe-cameron-treaty

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/09/uk-isolation-grows-eurozone-treaty

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/business/global/european-leaders-agree-on-fiscal-treaty.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/09/world/europe/

debt-crisis-bring-former-foes-poland-and-germany-closer-than-ever.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/08/world/europe/britain-suffers-as-a-bystander-to-europes-crisis.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/05/world/europe/leaders-struggle-for-deal-to-keep-euro-intact.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/world/europe/

french-president-warns-of-dire-consequences-if-euro-crisis-goes-unsolved.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/opinion/krugman-killing-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/02/opinion/the-fed-and-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/11/30/did-the-fed-go-far-enough

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/01/business/central-banks-move-together-to-ease-debt-crisis.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/opinion/germanys-denial-europes-disaster.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/business/ratings-firms-misread-signs-of-greek-woes.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/magazine/adam-davidson-european-finance.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/29/business/businesses-scramble-as-credit-tightens-in-europe.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/20/opinion/sunday/douthat-conspiracies-coups-and-currencies.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/19/business/global/

lenders-flee-debt-of-european-nations-and-banks.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/15/business/global/

as-european-nations-teeter-only-lenders-get-central-banks-help.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/15/business/global/

lack-of-transparency-leads-to-anxiety-among-banks.html

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/14/us-eurozone-idUSTRE7AC15K20111114

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/world/europe/

for-european-union-and-the-euro-a-moment-of-truth.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/11/business/global/sovereign-debt-turns-sour-in-euro-zone.html

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/10/us-eurozone-idUSTRE7A948U20111110

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/10/world/europe/

euro-fears-spread-to-italy-in-a-widening-debt-crisis.html

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/10/us-eurozone-democracy-idUSTRE7A861G20111110

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/10/us-eurozone-britain-cameron-idUSTRE7A92Q320111110

http://blogs.reuters.com/breakingviews/2011/11/09/don%E2%80%99t-count-your-chickens/

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/11/09/world/europe/europes-debt-problems.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/09/world/europe/support-for-berlusconi-ebbs-before-crucial-vote.html

eurozone crisis > Spain

2012

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/12/

world/europe/spain-evictions-create-an-austerity-homeless-crisis.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/spain-eurozone-impending-doom

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/spain-eu-rescue-funds-borrowing-costs

Spain borrowing costs

2012

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/spain-eu-rescue-funds-borrowing-costs

eurobonds

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/23/

eurozone-crisis-france-germany-divide

Tracking Europe's Debt Crisis

December 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/business/global/european-debt-crisis-tracker.html

fallout of the debt crisis

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/01/

business/central-banks-move-together-to-ease-debt-crisis.html

Europe’s financial crisis

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/

magazine/adam-davidson-european-finance.html

“suicide by economic crisis”

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/

opinion/sunday/bruni-on-old-walls-new-despair.html

U.S. Banks Tally Their Exposure to Europe’s

Debt Maelstrom January 29, 2012

http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/

u-s-banks-tally-their-exposure-to-europes-debt-maelstrom/

eurozone

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/feb/15/greece-forced-out-eurozone-venizelos

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/15/france-eurozone-row-uk-credit-downgrade

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/26/opinion/euro-zone-death-trip.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2009/jan/01/europe-creditcrunch

eurozone banks

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/16/uk-banks-greek-euro-exit

be forced out of

eurozone

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/feb/15/greece-forced-out-eurozone-venizelos

leave the euro

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/16/business/economy/

leaving-the-euro-may-be-better-than-the-alternative.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/10/opinion/how-greece-could-leave-the-euro.html

exit from euro / exit from the single currency

> Greece

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/21/

opinion/the-greece-issue-breeds-brinkmanship-in-the-eurozone.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/18/opinion/krugman-greece-as-victim.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/14/greece-on-edge-financial-collapse

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jun/14/spain-eu-rescue-funds-borrowing-costs

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/21/world/europe/

greek-crisis-poses-hard-choices-for-western-leaders.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/global/2012/may/16/cost-greek-exit-euro-emerges

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/14/euro-single-currency-greece

euro zone breakup

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/16/euro-breakup-eu-david-cameron

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/business/global/banks-fear-breakup-of-the-euro-zone.html

eurozone crisis / euro zone crisis / euro

crisis

2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/debt-crisis

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/18/opinion/brooks-the-technocratic-nightmare.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/world/europe/

for-european-union-and-the-euro-a-moment-of-truth.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/nov/09/european-debt-crisis-eurozone-breakup

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/10/world/europe/

euro-fears-spread-to-italy-in-a-widening-debt-crisis.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/08/world/europe/

greece-and-italy-sink-under-turmoil-as-euro-crisis-widens.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/06/business/global/europes-two-years-of-denials-trapped-greece.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/06/world/europe/political-uncertainty-lingers-in-greece.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/nov/03/greece-may-leave-euro-leaders-admit

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/business/global/03iht-group03.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/opinion/weak-economies-weak-leaders-greece.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/11/01/will-greece-destroy-the-euro-zone/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/02/opinion/how-to-prop-up-the-euro.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/world/europe/

greek-cabinet-backs-call-for-referendum-on-debt-crisis.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/02/business/global/

plan-to-leave-euro-for-drachma-gains-support-in-greece.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/27/world/europe/

german-vote-backs-bailout-fund-as-rifts-remain-in-talks.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/oct/27/eurozone-crisis-banks-50-greece

euro area / euro zone

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/15/business/global/

lack-of-transparency-leads-to-anxiety-among-banks.html

all over the euro zone

European credit markets

2012

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/04/opinion/an-insufficient-firewall.html

European Union EU

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/07/opinion/frances-ticking-time-bomb.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2014/may/22/

what-has-the-european-union-ever-done-for-you-video

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/jan/25/davos-soros-roubini-warnings-eurozone

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/02/world/europe/uk-and-future-in-mind-eu-plans-for-less-unanimity.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/audio/2011/dec/09/politics-weekly-podcast-europe-cameron-treaty

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/dec/09/cameron-eu-treaty-veto-analysis

Europe

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/opinion/europes-latest-try.html

Eurocrats

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/23/opinion/krugman-crisis-of-the-eurocrats.html

credit rating

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/

business/global/sp-cuts-its-rating-on-spain-citing-debt.html

rating firms

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/

business/ratings-firms-misread-signs-of-greek-woes.html

rating firms > Moody’s Investors Service

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/

business/global/moodys-downgrades-top-french-banks.html

rating firms > Standard & Poor’s

S&P's

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/

business/global/sp-cuts-its-rating-on-spain-citing-debt.html

downgrade

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/

business/global/sp-cuts-its-rating-on-spain-citing-debt.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/

business/global/moodys-downgrades-top-french-banks.html

downgrade

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/dec/15/

france-eurozone-row-uk-credit-downgrade

downgrade of debt ratings / rating downgrade

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/14/opinion/a-long-bleak-winter.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/14/business/global/

in-france-the-pain-of-rating-downgrade-is-especially-acute.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/14/business/global/euro-zone-downgrades-expected.html

Rob Rogers

political cartoon

GoComics

May 20, 2012

credit crunch

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/nov/30/

world-central-banks-act-credit-crunch

shun the dollar

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/07/business/07markets.html

dollar plunges

to all-time low against euro

slip below euro

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/dec/14/

euro-economic-policy-currencies-europe

lose

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2006/may/23/

ftse.frontpagenews

stock market > against the euro

A protesting officer from Greece's police

stands in a mock gallows

outside the Finance Ministry during an

anti-austerity protest in Athens

on September 6, 2012.

More than 4,000 officers, chanting "thieves,

thieves’’ and carrying black flags

took part in the march against expected new

pay cuts in the crisis-hit country.

Thanassis Stavrakis/Associated Press

Boston Globe > Big Picture > Austerity

protests

November 12, 2012

http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/2012/11/austerity_protests.html

austerity

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/may/31/

european-union-dream-austerity-disharmony

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/16/

opinion/europes-populist-backlash.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/24/world/europe/

vote-for-merkel-seen-as-victory-for-austerity.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/gallery/2012/nov/15/

austerity-protests-spain-portugal-pictures

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/02/opinion/

spanish-protests-german-prescriptions.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/

opinion/krugman-europes-austerity-madness.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/02/

business/global/in-euro-zone-austerity-seems-to-hit-its-limits.html

Boston Globe > Big Picture > Austerity protests

November 12, 2012

Matters of the economy are forefront in many

minds,

with economic issues dominating the recent American election

and the leadership change in China.

But in several countries in Europe,

economic debate is played out on the streets

with protests, petrol bombs, and strikes.

As the Eurozone struggles with the global financial crisis,

many member countries have turned

to

a series of spending cuts to health, education,

and other services and social programs.

Widespread protests against

these so-called austerity measures

have erupted in several countries

Gathered here are photographs

from the most heavily impacted nations in recent months,

including Spain, Greece, Portugal, and Italy

http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/2012/11/austerity_protests.html

austerity

Ireland

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/06/

business/global/despite-praise-for-its-austerity-

ireland-and-its-people-are-being-battered.html

Corpus of news articles

Economy >

Cryptocurrencies

Crash of the Bumblebee

July 29,

2012

The New York Times

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Last week

Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank, declared that his

institution “is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” — and

markets celebrated. In particular, interest rates on Spanish bonds fell sharply,

and stock markets soared everywhere.

But will the euro really be saved? That remains very much in doubt.

First of all, Europe’s single currency is a deeply flawed construction. And Mr.

Draghi, to his credit, actually acknowledged that. “The euro is like a

bumblebee,” he declared. “This is a mystery of nature because it shouldn’t fly

but instead it does. So the euro was a bumblebee that flew very well for several

years.” But now it has stopped flying. What can be done? The answer, he

suggested, is “to graduate to a real bee.”

Never mind the dubious biology, we get the point. In the long run, the euro will

be workable only if the European Union becomes much more like a unified country.

Consider, for example, the comparison between Spain and Florida. Both had huge

housing bubbles followed by dramatic crashes. But Spain is in crisis in a way

Florida isn’t. Why? Because when the slump hit, Florida could count on

Washington to keep paying for Social Security and Medicare, to guarantee the

solvency of its banks, to provide emergency aid to its unemployed, and more.

Spain had no such safety net, and in the long run, that has to be fixed.

But the creation of a United States of Europe won’t happen soon, if ever, while

the crisis of the euro is now. So what can be done to save the currency?

Well, why was the bumblebee able to fly for a while? Why did the euro seem to

work for its first eight or so years? Because the structure’s flaws were papered

over by a boom in southern Europe. The creation of the euro convinced investors

that it was safe to lend to countries like Greece and Spain that had previously

been considered risky, so money poured into these countries — mainly, by the

way, to finance private rather than public borrowing, with Greece the exception.

And for a while everyone was happy. In southern Europe, huge housing bubbles led

to a surge in construction employment, even as manufacturing became increasingly

uncompetitive. Meanwhile, the German economy, which had been languishing, perked

up thanks to rapidly rising exports to those bubble economies in the south. The

euro, it seemed, was working.

Then the bubbles burst. The construction jobs vanished, and unemployment in the

south soared; it’s now well above 20 percent in both Spain and Greece. At the

same time, revenues plunged; for the most part, big budget deficits are a

result, not a cause, of the crisis. Nonetheless, investors took flight, driving

up borrowing costs. In an attempt to soothe the financial markets, the afflicted

countries imposed harsh austerity measures that deepened their slumps. And the

euro as a whole is looking dangerously shaky.

What could turn this dangerous situation around? The answer is fairly clear:

policy makers would have to (a) do something to bring southern Europe’s

borrowing costs down and (b) give Europe’s debtors the same kind of opportunity

to export their way out of trouble that Germany received during the good years —

that is, create a boom in Germany that mirrors the boom in southern Europe

between 1999 and 2007. (And yes, that would mean a temporary rise in German

inflation.) The trouble is that Europe’s policy makers seem reluctant to do (a)

and completely unwilling to do (b).

In his remarks, Mr. Draghi — who I suspect understands all of this — basically

floated the idea of having the central bank buy lots of southern European bonds

to bring those borrowing costs down. But over the next two days German officials

appeared to throw cold water on that idea. In principle, Mr. Draghi could just

overrule German objections, but would he really be willing to do that?

And bond purchases are the easy part. The euro can’t be saved unless Germany is

also willing to accept substantially higher inflation over the next few years —

and so far I have seen no sign that German officials are even willing to discuss

this issue, let alone accept what’s necessary. Instead, they’re still insisting,

despite failure after failure — remember when Ireland was supposedly on the road

to rapid recovery? — that everything will be fine if debtors just stick to their

austerity programs.

So could the euro be saved? Yes, probably. Should it be saved? Yes, even though

its creation now looks like a huge mistake. For failure of the euro wouldn’t

just cause economic disruption; it would be a giant blow to the wider European

project, which has brought peace and democracy to a continent with a tragic

history.

But will it actually be saved? Despite Mr. Draghi’s show of determination, that

is, as I said, very much in doubt.

Crash of the Bumblebee, NYT, 29.7.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/30/opinion/

krugman-crash-of-the-bumblebee.html

On Old

Walls, New Despair

April 21,

2012

The New York Times

By FRANK BRUNI

LISBON

ANA LUISA NOGUEIRA started out looking for love. More and more, she found hate.

Not hate, exactly, although that’s a word she sometimes uses for it. Sorrow.

Anger. A broken faith in a future with much to offer.

About four years ago, as a weekend hobby, she began wandering Lisbon to

photograph the clusters of hearts and proclamations of ardor — the endearing

graffiti of romance — that she saw on the city’s buildings. But about two years

ago, on those same buildings, she noticed new images and messages sprouting.

Some raged at the Portuguese government, which had saddled the country with

debt. Some railed at Germany, which held the cards and the purse strings. Some

were just scrawled wails of grief.

As Europe’s financial crisis deepened and Portugal reeled, Lisbon’s walls

talked. “Abandon all hope, you who still believe in me,” they said, in

Portuguese. “Portugal died. R.I.P.”

That epitaph was long gone by earlier this month, when I joined Nogueira, 37,

for one of her walks. But we found other writings, including several with the

same blunt refrain of hopelessness.

“You will never own a house in your life,” it said. Except it said this with an

unprintable adjective before “your life.” It said this with vitriol and

heartache.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Portugal was a very different place, riding

high on the promise of the European Union, optimistic. So, to varying degrees,

were Greece, Spain, Ireland, Italy. Today they’re enduring a magnitude of

sacrifice, uncertainty and anxiety that trumps what America is going through,

not to belittle our hurt, and that serves as a warning and lesson.

What happens when the gap between what people thought lay ahead of them and what

they now confront is allowed to widen as quickly and as much as it has in these

countries? How do they adjust?

“They commit suicide in the public square,” said my friend Paulo Côrte-Real, an

economics professor in Lisbon, over dinner here. He was referring to

international headlines about a 77-year-old man who had recently shot himself in

front of the Greek Parliament and to “suicide by economic crisis,” a phrase that

several European newspapers now use. A story about the rise of such deaths

happened to appear in The Times the day after our dinner.

Maybe they flirt with far-right parties that scapegoat minorities and that

bemoan modernism and globalism. There have been reports and evidence of this in

Greece, Hungary, even France.

Maybe they take to the streets, loudly and repeatedly, as in Spain. Or maybe

they flee. Seemingly any young college graduate you talk to in Portugal — where

the unemployment rate is 15 percent overall but significantly higher for young

people, and where wages and benefits have plummeted — tells you about similarly

well-educated peers who have moved, with their skills and their ambitions,

elsewhere, leaving Portugal poorer in an additional way.

“The Netherlands, Germany, England, Canada, the U.S., Brazil, Angola, Denmark,”

said Joana Pacheco, 26, when I asked her to name places her friends had gone.

When I asked her how many of her friends she was talking about, she answered,

“All of them.”

She has an M.B.A. but works as a computer technician, making 800 euros (about

$1,000) a month, after taxes, in a job whose salary is trending downward. “Ten

years from now, we’ll be working for 300 euros,” she joked — sort of. She

recently applied for a position, any position, in a German municipality that

advertised jobs in a Portuguese newspaper. It was flooded with 8,000

applications, she said.

I met her through Nogueira, the photographer, whom I had met through a

Portuguese wine exporter I know. I had asked him, “What’s the mood like in

Portugal right now?”

He e-mailed me back a picture that Nogueira had just sent him: one of the darker

images she now sees and collects. On a blue doorway, in white, someone had

written, “Destiny is erased.”

Nogueira is a divorced mother of two girls, ages 8 and 10. She runs a private

kindergarten in Lisbon whose enrollment dropped to 85 students from 125 over the

last two years. Those departed children’s parents couldn’t afford it anymore.

Her income fell sharply as a result, and in order to pay for her own daughters’

private school, she had to move into a simpler apartment where she could live

rent-free, since her father owned it. But the bank could technically seize it at

any moment and probably will within two years, tops. The computer company over

which her father presided went bust, and he with it.

If forced to, she’ll put her daughters in public school, but she’s desperate to

keep them where they are, because the instruction in languages is so strong. “I

want them to learn English — better than me — and German,” she said. “I want

them to be able to leave.”

She doesn’t believe that Portugal will rebound anytime soon, in part because she

thinks its prosperity a decade ago was an illusion assisted by European Union

aid and extravagant, unnecessary infrastructure projects.

“Roads, roads, roads everywhere,” she said. “Portugal seemed perfect.” I

remembered having similar thoughts about Greece, which I covered from 2002 to

2004 for The Times. It had used European Union financial assistance and the

impetus of the looming Olympics to build, build, build.

And Greeks spent, spent, spent. Athens seemed to have three furniture stores and

two kitchen appliance retailers for each one in Italy, where I lived at the

time.

Nogueira took me to see wall writings. They’re not everywhere, but she knows

where to find them.

We spotted a stencil of the Portuguese flag beside the Greek flag and, snug

above them, this message: “Figure out the differences.” Another stencil, stamped

on many buildings, said: “All systems have a dead end.”

Many of the epigrams we saw over two days — and many others that she showed me

pictures of — are cryptic that way, more emotional than specific. Some are

reproduced in a slide show that accompanies this column online.

“Destroy what destroys you.” “The debt isn’t yours.” “I want to be happy.”

And in English, for whatever reason: “Until debt tear us apart.” “They say jump,

you say how high.” “Don’t give up.”

Perhaps the saddest one I saw was only one word. “Liberdade,” meaning freedom.

But with an arrow pointing heavenward. As if to say there was freedom only in

death?

About two months ago she persuaded a Lisbon souvenir store, Lisbon Lovers, to

turn her love photos — she still takes them, because romance hasn’t perished —

into a packet of 10 postcards.

She’d like to do something with the hate photos, too. But she senses that those

would be a much harder sell.

On Old Walls, New Despair, NYT, 21.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/opinion/

sunday/bruni-on-old-walls-new-despair.html

Europe’s Economic Suicide

April 15,

2012

The New York Times

By PAUL KRUGMAN

On Saturday

The Times reported on an apparently growing phenomenon in Europe: “suicide by

economic crisis,” people taking their own lives in despair over unemployment and

business failure. It was a heartbreaking story. But I’m sure I wasn’t the only

reader, especially among economists, wondering if the larger story isn’t so much

about individuals as about the apparent determination of European leaders to

commit economic suicide for the Continent as a whole.

Just a few months ago I was feeling some hope about Europe. You may recall that

late last fall Europe appeared to be on the verge of financial meltdown; but the

European Central Bank, Europe’s counterpart to the Fed, came to the Continent’s

rescue. It offered Europe’s banks open-ended credit lines as long as they put up

the bonds of European governments as collateral; this directly supported the

banks and indirectly supported the governments, and put an end to the panic.

The question then was whether this brave and effective action would be the start

of a broader rethink, whether European leaders would use the breathing space the

bank had created to reconsider the policies that brought matters to a head in

the first place.

But they didn’t. Instead, they doubled down on their failed policies and ideas.

And it’s getting harder and harder to believe that anything will get them to

change course.

Consider the state of affairs in Spain, which is now the epicenter of the

crisis. Never mind talk of recession; Spain is in full-on depression, with the

overall unemployment rate at 23.6 percent, comparable to America at the depths

of the Great Depression, and the youth unemployment rate over 50 percent. This

can’t go on — and the realization that it can’t go on is what is sending Spanish

borrowing costs ever higher.

In a way, it doesn’t really matter how Spain got to this point — but for what

it’s worth, the Spanish story bears no resemblance to the morality tales so

popular among European officials, especially in Germany. Spain wasn’t fiscally

profligate — on the eve of the crisis it had low debt and a budget surplus.

Unfortunately, it also had an enormous housing bubble, a bubble made possible in

large part by huge loans from German banks to their Spanish counterparts. When

the bubble burst, the Spanish economy was left high and dry; Spain’s fiscal

problems are a consequence of its depression, not its cause.

Nonetheless, the prescription coming from Berlin and Frankfurt is, you guessed

it, even more fiscal austerity.

This is, not to mince words, just insane. Europe has had several years of

experience with harsh austerity programs, and the results are exactly what

students of history told you would happen: such programs push depressed

economies even deeper into depression. And because investors look at the state

of a nation’s economy when assessing its ability to repay debt, austerity

programs haven’t even worked as a way to reduce borrowing costs.

What is the alternative? Well, in the 1930s — an era that modern Europe is

starting to replicate in ever more faithful detail — the essential condition for

recovery was exit from the gold standard. The equivalent move now would be exit

from the euro, and restoration of national currencies. You may say that this is

inconceivable, and it would indeed be a hugely disruptive event both

economically and politically. But continuing on the present course, imposing

ever-harsher austerity on countries that are already suffering Depression-era

unemployment, is what’s truly inconceivable.

So if European leaders really wanted to save the euro they would be looking for

an alternative course. And the shape of such an alternative is actually fairly

clear. The Continent needs more expansionary monetary policies, in the form of a

willingness — an announced willingness — on the part of the European Central

Bank to accept somewhat higher inflation; it needs more expansionary fiscal

policies, in the form of budgets in Germany that offset austerity in Spain and

other troubled nations around the Continent’s periphery, rather than reinforcing

it. Even with such policies, the peripheral nations would face years of hard

times. But at least there would be some hope of recovery.

What we’re actually seeing, however, is complete inflexibility. In March,

European leaders signed a fiscal pact that in effect locks in fiscal austerity

as the response to any and all problems. Meanwhile, key officials at the central

bank are making a point of emphasizing the bank’s willingness to raise rates at

the slightest hint of higher inflation.

So it’s hard to avoid a sense of despair. Rather than admit that they’ve been

wrong, European leaders seem determined to drive their economy — and their

society — off a cliff. And the whole world will pay the price.

Europe’s Economic Suicide, NYT, 15.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/16/opinion/

krugman-europes-economic-suicide.html

Europe’s Failed Course

February

17, 2012

The New York Times

Struggling

euro-zone economies like Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy cannot cut their way

back to growth. Demanding rigid austerity from them as the price of European

support has lengthened and deepened their recessions. It has made their debts

harder, not easier, to pay off.

This is not an issue of philosophical debate. The numbers are in.

As The Times’s Landon Thomas Jr. reported this week, Portugal has met every

demand from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. It has cut

wages and pensions, slashed public spending and raised taxes. Those steps have

deepened its recession, making it even less able to repay its debts. When it

received a bailout last May, Portugal’s ratio of debt to gross domestic product

was 107 percent. By next year, it is expected to rise to 118 percent. That ratio

will continue to rise so long as the economy shrinks. That is, indeed, the very

definition of a vicious circle.

Meanwhile, shrinking demand and fears of a contagious collapse keep pushing more

European countries toward the danger zone of unsustainable debt.

Why are Europe’s leaders so determined to deny reality? Chancellor Angela Merkel

of Germany and President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, in particular, seem unable

to admit that they got this wrong. They are still captivated by the illogical

but seductive notion that every country can emulate Germany’s export-driven

model without the decades of public investment and artificially low exchange

rates that are crucial to Germany’s success.

Mrs. Merkel also seems determined to pander to the prejudices of German voters

who believe that suffering is the only way to purge Greece and other southern

European countries of their profligate ways.

There’s no question that Greece has behaved inexcusably, spending more than it

could afford, failing to collect taxes from some of its richest citizens and

fudging its books. And while we sympathize with Greek protests against excessive

austerity, we have no patience with politicians who continue to drag their feet

over pro-growth reforms and privatizations. But the cure is neither collective

punishment nor induced recession. Europe must be willing to help Greece grow out

of its problems — on the condition that Greek politicians finally commit

themselves to market reforms.

Under strong pressure from international investors, euro-zone leaders have

recently adjusted some of their policies. Europe’s central bank has injected

much needed liquidity into the Continent’s banking system. Plans are finally

under way to add money to a chronically underfinanced European Union bailout

fund. But until they abandon the mistaken belief that austerity is the way to

debt relief, even those steps won’t be enough.

With Greece rapidly approaching the day (probably next month) when it can no

longer pay government salaries and foreign creditors, Europe still has not

released needed bailout money. It is not clear whether Mrs. Merkel and Mr.

Sarkozy and others are playing chicken with Athens or think they could withstand

Greece defaulting and leaving the euro zone. The risks are enormous.

At a minimum, a Greek default would send damaging aftershocks rippling through

government finances and banks across Europe. The ideal and the practice of a

united Europe would suffer a major blow. Those are high prices for all of Europe

to pay for clinging to a failed idea.

Europe’s Failed Course, NYT, 17.2.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/18/opinion/europes-failed-course-

on-the-economy.html

Europe

v. World

February

14, 2012

The New York Times

By EDWIN M. TRUMAN

Washington

FOR the third time in a century, a bitter conflict fueled by historic grievances

has erupted in Europe, with the United States looking from afar and hoping not

to get involved. Of course, this is not being fought on the battlefields but in

the arcane arenas of international finance. But as in World War I, which

President Woodrow Wilson once dismissed as “a drunken brawl,” and in World War

II, which America formally stayed out of until Pearl Harbor, the crisis over the

euro will require further American involvement — whether we like it or not.

Currently, the United States is discouraging the International Monetary Fund and

its non-European members from promising additional financial assistance to

Europe.

The American posture is understandable and, at one level, sensible. With our own

debt and deficit problems, we and other countries can be forgiven for feeling

that it not up to us to extricate Europe from its mistakes and excesses.

President Obama, facing a tough re-election fight, is hardly in a position to

offer financial aid to Europe. Just as Washington wants Europe to do more to

enhance its political and military security, so is it appropriate to demand that

Europe do more on its own with respect to its economic and financial security.

But policy passivity risks exacerbating the European crisis and its

macroeconomic effects. The United States must show more leadership. First, it

must be bolder and more public in setting conditions on Europe’s loan programs.

Then, if Europe finally responds convincingly, the United States should rally

the rest of the world in a supporting role.

For two years, Europe has dithered over creating a financial firewall to prevent

the financial meltdown’s spreading from Greece. Little has come of the

discussions. Europe now needs a financial safety net to rescue itself from a

self-made conflagration that threatens itself and the rest of the world.

As a measure of the consternation outside of Europe, the economic forecasts

released recently by the I.M.F. projected global growth this year at 1.2

percentage points lower than last spring, a deterioration that is largely

attributable to mismanagement of the euro crisis. No region of the world has

been spared. The loss in global output amounts to $1 trillion.

Two months ago, European leaders asked the I.M.F. and the rest of the world for

help, while pledging to make their own financial contribution, channeled through

the I.M.F. The United States does not need to put up money, but it has been slow

to respond positively. It is time for Washington to insist that I.M.F.

assistance be accompanied by conditions on economic and financial policies in

the euro area. There should be conditions attached not just to programs to

support Greece, Ireland, Portugal and potentially Italy and Spain but also to

euro-area policies more broadly because this is a euro-area crisis.

Four conditions are appropriate.

First, countries that can — that is, those where the ratio of government debt to

gross domestic product is 90 percent or less — should reverse their projected

budget tightening in 2012 and 2013. Those countries are Austria, Finland,

France, Slovenia — and, above all, Germany.

Second, the European Central Bank should lower its refinancing rate to 0.25

percent from 1 percent — an action that it has resisted because of an

unjustified fear of inflation.

Third, euro-area authorities should set aside at least $1 trillion for a

European financial safety net — a far larger amount than what has been publicly

discussed so far — to persuade markets to stop betting against debt markets of

solvent countries.

Fourth, new loans from the euro area, channeled through the I.M.F back to the

euro area, should not be repaid until all existing I.M.F. loans to euro-area

countries have been entirely repaid. A change in this treatment is necessary

before China, the Persian Gulf countries and other potential contributors are

comfortable with throwing a lifeline to a region more prosperous than their own

countries.

If these four conditions are met, then the United States should drop its tacit

opposition to a proposal by Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the

I.M.F. and a former French finance minister, to raise $500 billion to support

Europe and actively encourage those countries with the political and financial

capacity to participate in the I.M.F. component of a European financial safety

net.

Ironically, the I.M.F. will be turning to these emerging markets and developing

countries for help just as the euro debt crisis has delayed the timetable for

long-promised increases in voting power for those nations at the I.M.F. Given

the economic and financial damage inflicted by Europe on the rest of the world,

the United States must insist that these promises be strengthened, and speedily

fulfilled.

Edwin M.

Truman,

a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute

for International Economics,

was director of international finance

at the Federal Reserve Board from 1977 to

1998

and assistant secretary of the Treasury

for international affairs from 1998

to 2001.

He served as a counselor to the Treasury secretary in 2009.

Europe v. World, NYT, 14.2.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/15/opinion/europe-v-world.html

Why Is

Europe a Dirty Word?

January 14,

2012

The New York Times

By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF

PARIS

QUELLE horreur! One of the uglier revelations about President Obama emerging

from the Republican primaries is that he is trying to turn the United States

into Europe.

“He wants us to turn into a European-style welfare state,” warned Mitt Romney.

Countless versions of that horrific vision creep into Romney’s speeches,

suggesting that it would “poison the very spirit of America.”

Rick Santorum agrees, fretting that Obama is “trying to impose some sort of

European socialism on the United States.”

Who knew? Our president is plotting to turn us into Europeans. Imagine:

It’s a languid morning in Peoria, as a husband and wife are having breakfast.

“You’re sure you don’t want eggs and bacon?” the wife asks. “Oh, no, I prefer

these croissants,” the husband replies. “They have a lovely je ne sais quoi.”

He dips the croissant into his café au-lait and chews it with zest. “What do you

want to do this evening?” he asks. “Now that we’re only working 35 hours a week,

we have so much more time. You want to go to the new Bond film?”

“I’d rather go to a subtitled art film,” she suggests. “Or watch a pretentious

intellectual television show.”

“I hear Kim Kardashian is launching a reality TV show where she discusses

philosophy and global politics with Bernard-Henri Lévy,” he muses. “Oh, chérie,

that reminds me, let’s take advantage of the new pétanque channel and host a

super-boules party.”

“Parfait! And we must work out our vacation, now that we can take all of August

off. Instead of a weekend watching ultimate fighting in Vegas, let’s go on a

monthlong wine country tour.”

“How romantic!” he exclaims. “I used to worry about getting sick on the road.

But now that we have universal health care, no problem!”

Look out: another term of Obama, and we’ll all greet each other with double

pecks on the cheek.

Yet there is something serious going on. The Republican candidates unleash these

attacks on Obama because so many Americans have in mind a caricature of Europe

as an effete, failed socialist system. As Romney puts it: “Europe isn’t working

in Europe. It’s not going to work here.”

(Monsieur Romney is getting his comeuppance. Newt Gingrich has released an

attack ad, called “The French Connection,” showing clips of Romney speaking the

language of Paris. The scandalized narrator warns: “Just like John Kerry, he

speaks French!”)

But the basic notion of Europe as a failure is a dangerous misconception. The

reality is far more complicated.

What is true is that Europe is in an economic mess. Quite aside from the current

economic crisis, labor laws are often too rigid, and the effect has been to make

companies reluctant to hire in the first place. Unemployment rates therefore are

stubbornly high, especially for the young. And Europe’s welfare state has been

too generous, creating long-term budget problems as baby boomers retire.

“The dirty little secret of European governments was that we lived in a way we

couldn’t afford,” Sylvie Kauffmann, the editorial director of the newspaper Le

Monde, told me. “We lived beyond our means. We can’t live this lie anymore.”

Yet Kauffmann also notes that Europeans aren’t questioning the basic European

model of safety nets, and are aghast that Americans tolerate the way bad luck

sometimes leaves families homeless.

It’s absurd to dismiss Europe. After all, Norway is richer per capita than the

United States. Moreover, according to figures from the United States Bureau of

Labor Statistics, per-capita G.N.P. in France was 64 percent of the American

figure in 1960. That rose to 73 percent by 2010. Zut alors! The socialists

gained on us!

Meanwhile, they did it without breaking a sweat. The Bureau of Labor Statistics

says that employed Americans averaged 1,741 hours at work in 2010. In France,

the figure was 1,439 hours.

If Europe was as anticapitalist as Americans assume, its companies would be

collapsing. But there are 172 European corporations among the Fortune Global

500, compared with just 133 from the United States.

Europe gets some important things right. It has addressed energy issues and

climate change far more seriously than America has. It now has more economic

mobility than the United States, partly because of strong public education

systems. America used to have the highest proportion of college graduates in the

world; now France and Britain are both ahead of us.

Back in 1960, French life expectancy was just a few months longer than in the

United States, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development. By 2009, the French were living almost three years longer than we

were.

So it is worth acknowledging Europe’s labor rigidities and its lethargy in

resolving the current economic crisis. Its problems are real. But embracing a

caricature of Europe as a failure reveals our own ignorance — and chauvinism.

Why Is Europe a Dirty Word?, NYT, 1.14.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/opinion/sunday/kristof-

why-is-europe-a-dirty-word.html

Downgrade of Debt Ratings

Underscores Europe’s Woes

January 13, 2012

The New York Times

By LIZ ALDERMAN and RACHEL DONADIO

PARIS — Standard & Poor’s downgraded the credit ratings of

France, Italy and seven other European countries on Friday, a move that may have

more symbolic than fundamental financial impact but served as a reminder that

Europe’s economic woes were far from over.

Another memory jog came Friday from Greece, the original source of Europe’s debt

troubles. Talks hit a snag between the new Greek government and the banks and

other private investors that Athens hopes will agree to take losses on their

debt so that Greece can avoid a default.

Together, those developments underscore that even as Europe’s debt turmoil

enters its third year, no clear solutions are yet in sight — despite recent

signs that a new lending program by the European Central Bank might be easing

financial market pressures.

S.& P. warned in December that it might downgrade many of the 17 nations that

share the euro, largely because it said European politicians were moving too

slowly to strengthen the monetary union and because the euro zone’s problems

were propelling Europe toward its second recession in three years.

European politicians, in turn, criticized S.& P.’s downgrade plans as providing

no meaningful new information to investors but simply stoking a sense of crisis.

To some extent, the prospect of rating downgrades has already been priced into

recent bond auctions by Italy, Spain and other countries. Italy, in fact,

completed another fairly successful bond auction on Friday, even as rumors of

the downgrades had begun to swirl.

But the downgrades may now add to the borrowing costs of the nations affected.

Some commercial banks that are required to hold only the highest-rated

government securities will have to replace French bonds with other assets, like

bonds of Germany.

And the downgrades cannot help but add to the gloom pervading Europe’s economic

climate.

“Today’s rating actions are primarily driven by our assessment that the policy

initiatives that have been taken by European policy makers in recent weeks may

be insufficient to fully address ongoing systemic stresses in the euro zone,”

S.&. P said.

Finance Minister François Baroin of France said Friday that the loss of his

country’s pristine AAA rating, cut a notch to AA+, was “not good news” but was

“not a catastrophe.” He insisted that the country was headed in the right

direction and that no ratings agency would dictate the policies of France, which

has Europe’s second-biggest economy, behind Germany’s.

But the downgrades pose fresh challenges for Europe’s political leaders,

particularly President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, who is expected to run for

re-election this spring and had long cited his country’s AAA credit rating as a

badge of honor.

In August, when S.& P. cut the United States a notch from its top-rank AAA

rating, markets briefly plunged. But bond investors have continued to flock to

the debt of the United States, which as the world’s largest economy has retained

the perception of a financial safe haven. That has kept the United States

government’s interest rates at very low levels. But none of the countries

downgraded on Friday can necessarily count on such a reaction.

After Friday, the only euro zone nations retaining their top AAA ratings are

Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and Luxembourg.

Italy and Spain, which are considered the two big euro-zone economies most

vulnerable to an escalation of debt problems, both were downgraded two notches,

Italy to BBB+ and Spain to A.

“It will make it harder to erect firewalls around struggling euro zone economies

and convince investors that things are more sustainable,” said Simon Tilford,

the chief economist for the Center for European Reform in London.

Stocks were down broadly if not deeply in Europe and the United States on

Friday, as rumors of the downgrades preceded S.& P.’s announcement, which came

after the close of trading on Wall Street. And the euro fell to a 16-month low

against the dollar.

Just as significant as the ratings downgrades may be the suspension on Friday of

the creditor talks in Greece — whose debt S.& P. long ago gave junk status.

In October, the European Union pledged to write off 100 billion euros ($127.8

billion) of Greece’s debt if bondholders would agree to voluntarily accept 50

percent losses on their Greek holdings. Such an arrangement, known as

private-sector involvement, or P.S.I., has been pushed by Chancellor Angela

Merkel of Germany as a way of forcing banks, not only European taxpayers, to

foot the bill for bailing out Greece.

But talks broke down on Friday between Greece and the commercial banks.

“Discussions with Greece and the official sector are paused for reflection on

the benefits of a voluntary approach,” the Institute of International Finance,

which negotiates on behalf of the banks, said in a statement on Friday, after

its leader, Charles Dallara, left Athens.

“Unfortunately, despite the efforts of Greece’s leadership, the proposal put

forward,” the statement added, “has not produced a constructive consolidated

response by all parties.”

The reference to a “voluntary approach” might be a not-so-subtle message that if

Europe pushed too hard on this point, then the creditors could no longer accept

the agreement as a voluntary one. That is crucial, because an involuntary debt

revamping would be seen by creditors as a default — a step Greece and Europe are

trying hard to avoid.

If Greece defaults, it could set off the activation of credit default swaps — a

type of financial insurance. If the issuers of that insurance have to start

paying up, many analysts fear the same sort of falling dominoes of i.o.u.’s that

cascaded through the financial industry after the subprime mortgage market

collapsed in the United States in 2007 and 2008.

Talks are expected to resume next week. If Greece fails to persuade enough

bondholders to take voluntary losses, it may pass a law activating clauses in

the bonds that would force creditors to take losses.

“We should be ready, if we don’t have 100 percent participation and if Europe

doesn’t want to give us more money,” Christos Staikouras, a member of the Greek

Parliament from the center-right New Democracy opposition party and its economic

spokesman, said in an interview.

The tense negotiations over Greece’s debt come as the Greek government struggles

to find a consensus to pass the budget reforms demanded by its so-called troika

of lenders — the European Central Bank, European Union and International

Monetary Fund — in exchange for releasing the next installment of bailout money,

a 30 billion euro ($38.3 billion) payout scheduled to be released in March.

The Greek uncertainties only add to the regional doubt that helped set off the

S.& P. downgrades. Europe’s economy, having barely clawed its way out of a

recession three years ago, is again tipping into a new one. France, Spain,

Greece and Portugal are already in recessions, and Italy is expected to head

into one as a result of belt-tightening measures being pushed by its new prime

minister, Mario Monti.

Austria, the other country whose AAA rating was cut a notch on Friday, could be

in for trouble if the political turmoil in neighboring Hungary affects Austrian

banks, S.& P. said.

Even mighty Germany, with most of its neighbors in a downturn, is also expected

to slip into a shallow recession this year. On Friday, S.& P. kept Germany’s

ratings untouched, citing its continued competitiveness and financial rigor. But

it said it could lower Germany’s rating if its debt, now 80 percent of gross

domestic product, reached 100 percent.

David Jolly and Steven Erlanger

contributed reporting from Paris,

Landon Thomas Jr. from London

and Gaia Pianigiani from Rome.

Downgrade of Debt Ratings Underscores

Europe’s Woes, NYT, 13.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/14/business/global/

euro-zone-downgrades-expected.html

Austerity Reigns Over Euro Zone

as Crisis Deepens

January 1,

2012

The New York Times

By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ

Europe’s

leaders braced their nations for a turbulent year, with their beleaguered

economies facing a threat on two fronts: widening deficits that force more

borrowing but increasing austerity measures that put growth further out of

reach.

Saying that Europe was facing its “harshest test in decades,” Chancellor Angela

Merkel of Germany warned on New Year’s Eve that “next year will no doubt be more

difficult than 2011” — a marked change in tone from a year ago, when she praised

Germans for “mastering the crisis as no other nation.”

Her blunt message was echoed in Italy, France and Greece, the epicenter of the

debt crisis, where Prime Minister Lucas Papademos asked for resolve in seeing

reforms through, “so that the sacrifices we have made up to now won’t be in

vain.”

While the economic picture in the United States has brightened recently with

more upbeat employment figures, Europe remains mired in a slump. Most economists

are forecasting a recession for 2012, which will heighten the pressure

governments and financial institutions across the Continent are seeing.

Adding to the gloomy outlook is the prospect of a downgrade in France’s sterling

credit rating, a move that analysts say could happen early in the new year and

have wide-ranging consequences on efforts to stabilize Europe’s finances.

Despite criticism from many economists, though, most European governments are

sticking to austerity plans, rejecting the Keynesian approach of economic

stimulus favored by Washington after the financial crisis in 2008, in a bid to

show investors they are serious about fiscal discipline.

This cycle was evident on Friday, when Spain surprised observers by announcing a

larger-than-expected budget gap for 2011 even as the new conservative government

there laid out plans to increase property and income taxes in 2012.

Indeed, even in the country where the crisis began, Greece, the cycle of

spending cuts, tax increases and contraction has not resulted in a course

correction, and the same path now lies in store for much larger economies like

those of Italy and Spain.

“Every government in Europe with the exception of Germany is bending over

backwards to prove to the market that they won’t hesitate to do what it takes,”

said Charles Wyplosz, a professor of economics at the Graduate Institute of

Geneva. “We’re going straight into a wall with this kind of policy. It’s sheer

madness.”

Rather than the austerity measures now being imposed, Mr. Wyplosz said he would

like to see governments halt the recent tax increases and spending reductions,

and instead cut consumption taxes in a bid to encourage consumer spending. More

belt-tightening, he said, increases the likelihood that Europe will see a “lost

decade” of economic torpor like Japan faced in the 1990s.

In fact, economists and strategists on both sides of the Atlantic have been

steadily ratcheting down their growth expectations for 2012.

“Europe is likely to have a meaningful recession in 2012,” said Tobias

Levkovich, Citigroup’s chief equity strategist. While Mr. Levkovich does not see

that as a significant threat to the bottom line of most American businesses — he

estimates that Europe accounts for about 8.5 percent of sales for the typical

company in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index — the psychological effects on

global markets will be magnified if political opposition to austerity increases.

“Powerful street protests could bring it back to the front pages,” he said.

“We’ve seen episodic crises in Europe over the past two years. It’s a recurring

event.” He expects Europe to remain a key worry for investors worldwide in 2012.

Neville Hill, head of European economics at Credit Suisse, expects gross

domestic product in the euro zone to shrink by 0.5 percent in 2012, with the

worst of the pain being felt in the first quarter. At the same time, borrowing

needs will remain elevated, with Italy and Spain planning to raise more than 100

billion euros in the first quarter alone.

“We shouldn’t underestimate the scale of the challenge the euro zone faces in

early 2012,” Mr. Hill said. “Italian and Spanish sovereign borrowers are at the

foot of the mountain, rather than the top. The first quarter is a crunch point.”

The Continent’s economic outlook will take center stage on Jan. 9, when Mrs.

Merkel and President Nicolas Sarkozy of France will discuss a new fiscal treaty

intended to impose stringent budget requirements on European Union nations. Then

on Jan. 30, European Union leaders will gather in Brussels to discuss ways to

spur growth.

There are some bright spots as Europe enters 2012. The recent drop of the euro

currency against foreign rivals like the yen and the dollar makes European

exports more competitive — a critical advantage for Germany, Europe’s largest

exporter and its largest economy. German unemployment now stands at 5.5 percent,

the lowest since German reunification.

About 15 percent of the euro zone’s gross domestic product comes from German

consumer spending, more than the contribution of Greece, Spain, Portugal and

Ireland combined, according to Mr. Hill.

The first test for the Continent will come this Thursday, when France is

expected to raise as much as 8 billion euros. On Jan. 12, Spain plans to auction

3 billion euros worth of euro debt, followed by Italy the next day with 9

billion euros. Along with governments tapping the market, European banks are

also expected to keep borrowing heavily as loans come due.

In the first quarter of 2012, about 215 billion euros worth of euro zone bank

debt must be rolled over, according to Julian Callow, chief European economist

at Barclays.

Over all, Mr. Callow said, “the big picture is one of very restricted

visibility. The choice is whether you get a mild or more severe recession.”

Despite a move by the European Central Bank on Dec. 21 to provide 489 billion

euros in cheap, long-term credit to European banks, the central bank remains

reluctant to take more aggressive steps to become the lender of the last resort

as the Federal Reserve did in the wake of the financial crisis in the United

States in 2008.

In particular, the European bank has remained steadfast in its opposition to

buying up sovereign debt outright, for fear of encouraging a return to the kind

of deficit spending that got countries like Greece — which continues to rely on

bailout money — into trouble in the first place. But the bank’s move to inject

liquidity on Dec. 21 was seen as a kind of backdoor way of supporting government

bonds, since it is likely that a substantial portion of the money the banks

borrowed was quickly parked in sovereign bonds.

Rates have fallen since then, especially on short-term notes. At an auction

Wednesday of Italian six-month bills, the yield fell to 3.25 percent from a

record 6.5 percent yield a month earlier. But plenty of caution remains — a sale

by Italy Thursday of longer-term debt, including 10-year bonds, managed to raise

only 7 billion euros instead of the 8.5 billion euros that had been forecast.

“Europe is going about this the hard way,” Mr. Callow added. “It’s not really

using the central bank to alleviate these pressures in a dominant way.”

In addition, with governments in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland planning

more austerity measures, Mr. Callow said, “this is likely to fuel growing

political and social tension. The markets will be closely watching the level of

domestic support.”

Melissa Eddy

contributed reporting.

Austerity Reigns Over Euro Zone as Crisis Deepens, NYT, 1.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/02/business/global/

in-euro-zone-austerity-seems-to-hit-its-limits.html

As Tension Rises in France,

Harsh Talk With Britain

December 16, 2011

The New York Times

By LIZ ALDERMAN

PARIS — To the long list of victims emerging from Europe’s

financial crisis, make room for a new one: the “Entente Cordiale” between

Britain and France.

A week after the British prime minister, David Cameron, refused to sign a

Europe-wide pact that leaders had hoped would stabilize the euro zone, a

cross-Channel spat has escalated into a full-blown war of words. Fears in Paris

have reached a fever pitch over the prospect that France is about to lose its

triple-A credit rating, the highest available.

President Nicolas Sarkozy started preparing the country this week for the

imminent loss of its gilt-edged status, though Fitch Ratings on Friday affirmed

France’s top credit rating while changing its outlook to negative.

A downgrade by Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, which has put France on

review with a negative outlook, became more likely last week after a summit

meeting of European Union leaders was widely declared a flop.

But in the last two days, French officials have unleashed a diatribe suggesting

that Britain, not France, is far more deserving of a downgrade.

“At this point, one would prefer to be French than British on the economic

level,” the French finance minister, François Baroin, declared Friday.

The ruckus comes as Mr. Sarkozy prepares for a tense re-election campaign

heading into what promises to be a gloomy year economically for the country and

much of the rest of Europe.

Troubled by the crisis in the euro zone, France is probably already in a

recession, the government and the central bank warned this week, with a decline

in economic activity expected to continue at least through March. Business and

consumer sentiment have deteriorated, and unemployment is stuck at just below 10

percent.

Paris has embraced two austerity plans since the summer in a bid to reduce the

country’s chronic budget deficit and meet the demands from Berlin to set an

example for the rest of Europe to follow. Officials say those steps are also

necessary to prevent France’s international borrowing costs from rising to

unhealthy levels because of investors’ concern that France is losing the

capacity to foot a growing bill from the euro zone crisis.

The verbal onslaught seemed aimed at deflecting attention from those problems.

Within hours, headlines blared from British news Web sites taking exception to

the perceived French snub.

“The gall of Gaul!” read The Mail Online. An article in The Guardian accused

French politicians of descending “to the level of the school playground.”

Both countries are in poor economic shape. While the French are not suffering

anything like the distress being felt in Greece, Portugal and Ireland — which

cannot pay their bills without help from the European Union and the

International Monetary Fund — the French government is not immune to speculators

who see its rising debt levels as making it vulnerable to attacks in the bond

market.

France’s debt as a percentage of gross domestic product was 82.3 percent in

2010, a figure that is expected to rise in the coming years even after it

tightens its belt. Britain’s debt was 75 percent of its G.D.P. and also rising

fast despite a stringent austerity program that is, at least for now, only

adding to the country’s economic woes.

In France, the budget deficit was 7.1 percent of G.D.P. last year. Mr. Sarkozy

has pledged to reduce it to 3 percent by 2013, partly through higher taxes, but

he has been reluctant to spell out which social programs may have to be cut as

well, out of fear of further alienating already disenchanted voters.

A looming recession is making that fiscal dilemma even worse by adding to social

costs and reducing tax revenue.

“It is very bad news for people, because it means the unemployment rate will

increase as more firms will have to fire people or go bankrupt in the private

sector,” said Jean-Paul Fitoussi, a professor of economics at L’Institut

d’Études Politiques in Paris. “It’s also bad news for politicians. They are in a

kind of a trap because they have to say to the people that there is nothing they

can do for them.”

As he walked to his job in an affluent suburb of Paris, Steve Kamguea, 22, an

entry-level banker at AlterValor Finances, said he saw little hope for a revival

of economic growth in France.

“With the problems in the euro zone hitting us, people are anxious about what

will happen in the future,” Mr. Kamguea said. “Purchasing power is already low,

and it’s hard to get by,” he added, shielding his face from a driving cold rain.

“Many people don’t know if they can find a job, and if they do, how much it will

pay.”

The prospect of losing France’s sterling credit rating may throw more fuel on

the fire. Both Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s said they would review all European

Union countries for a possible downgrade soon after last week’s summit meeting.

On Friday, Fitch left France off a list of six euro zone countries that it

warned could be downgraded soon. The agency named Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland,

Italy, Spain and Slovenia.

But Fitch, in a separate statement reaffirming France’s AAA rating, revised its

outlook on long-term debt to negative from stable. It suggested that France

could lose the top rating over the next two years, saying it was the most

exposed of other euro countries to a further intensification of the crisis.

As for last week’s euro crisis summit and actions by the European Central Bank

to ease a banking credit crunch, Fitch said the commitments “were not sufficient

to put in place a fully credible financial firewall to prevent a self-fulfilling

liquidity and even solvency crisis for some non-AAA euro area sovereigns. In the

absence of a comprehensive solution, the euro zone crisis will persist and

likely be punctuated by episodes of severe financial market volatility.”

In the six-country announcement, Fitch was even more severe, concluding that

after the summit meeting, “a ‘comprehensive solution’ to the euro zone crisis

was technically and politically beyond reach.”