|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Music

Spirituals, Gospel,

Doo Wop, Jazz

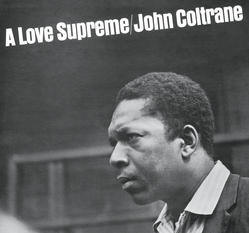

John Coltrane

Photograph:

Francis Wolff

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/coltrane/

art_photos.htm - broken link

John Coltrane

Impulse

http://www.vervemusicgroup.com/

artist.aspx?ob=ros&src=lb&aid=2660 - broken link

John Coltrane

https://bohemian.com/papers/

sonoma/12.13.01/gifs/coltrane-0150.jpg

John Coltrane

Impulse

http://www.vervemusicgroup.com/

artist.aspx?ob=ros&src=lb&aid=2660 - broken link

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Love_Supreme

doo wop

USA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Doo-wop

https://www.npr.org/2023/03/18/

1164572532/parliament-funkadelic-singer-

clarence-fuzzy-haskins-obituary-dead

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/28/

632661834/american-anthem-

dancing-in-the-street-martha-vandellas

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/

obituaries/eugene-pitt-doo-wop-singer-with-staying-power-

dies-at-80.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/07/

arts/music/carlo-mastrangelo-

a-doo-wop-voice-for-dion-and-the-belmonts-dies-at-78.html

doo wopper

gospel USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/02/28/

nx-s1-5289879/black-gospel-music-rare-recordings-archive-history

https://www.npr.org/2024/10/07/

1105956461/cissy-houston-has-died

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/may/10/

amazing-grace-review-aretha-franklin-gospel-album-documentary

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/01/

643828580/at-aretha-franklins-funeral-gospel-was-the-heart-and-backbone

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/04/

616845894/clarence-fountain-leader-and-founding-member-of-blind-boys-of-alabama-

dies-at-88

https://www.npr.org/2018/03/19/

594349558/the-indelible-career-of-gospel-innovator-dr-bobby-jones

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/11/

arts/music/linda-hopkins-died-gospel-singer-on-broadway.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/06/

arts/music/evelyn-starks-hardy-founder-of-the-gospel-harmonettes-dies-at-92.html

https://www.npr.org/2006/02/12/

5202677/a-40-year-friendship-built-on-gospel-music

https://www.nytimes.com/1976/05/02/

archives/ray-charles-adds-gospel-overtones-to-his-repertory.html

the handclapping

backbeat of gospel

call-and-response patterns of black gospel music

America, USA > slaves > Black

spirituals

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/05/

t-magazine/black-spirituals-poetry-resistance.htm

rag / ragtime

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2022/02/07/

1078314203/reconsidering-scott-joplins-the-entertainer

southern rag

jazz

UK / USA

https://www.npr.org/music/genres/

jazz/

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

jazz

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/mar/06/

roy-ayers-jazz-funk-pioneer-everybody-loves-the-sunshine-dies

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/10/

arts/music/bill-holman-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2022/05/06/

1096885184/who-says-big-band-jazz-is-for-old-people-not-this-teenage-composer

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/

913619163/stanley-crouch-towering-jazz-critic-dead-at-74

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/16/

obituaries/stanley-crouch-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/05/

793722676/how-to-like-jazz-for-the-uninitiated

https://www.npr.org/2018/08/17/

639519163/all-the-things-you-are-aretha-franklin-life-in-jazz

http://www.npr.org/2017/02/24/

517042756/jazz-on-film-and-the-problem-of-the-mad-creative-genius

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/oct/27/

verve-records-jazz-norman-granz

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/06/

arts/music/dave-brubeck-jazz-musician-dies-at-91.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/22/

archives/bill-cobham-leads-his-jazzrock-band-at-the-bottom-line.html

West

coast jazz USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/10/

arts/music/bill-holman-dead.html

jazz-funk

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/mar/06/

roy-ayers-jazz-funk-pioneer-everybody-loves-the-sunshine-dies

jazz-rock USA

https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/22/

archives/bill-cobham-leads-his-jazzrock-band-at-the-bottom-line.html

jazz greats

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/06/

arts/music/phoebe-jacobs-publicist-for-jazz-greats-is-dead-at-93.html

jazz giants

USA

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/08/16/

hearing-music-in-photos-of-jazz-giants/

jazz club > UK > London >

Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club / Ronnie Scott's /

Ronnie’s UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/08/

arts/music/ronnies-jazz-club-documentary.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/oct/06/

happy-50th-ronnie-scotts

1970s > USA > Ney

York venues > Studio Rivbea USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/22/

arts/music/sam-rivers-centennial-studio-rivbea.html

jazz slang USA

http://www.npr.org/event/music/467259732/

a-dive-into-jazz-slang-you-dig - February 18, 2016

jazz zealot USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/

movies/jean-bach-jazz-documentarian-and-fan-dies-at-94.html

jazz documentarian USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/

movies/jean-bach-jazz-documentarian-and-fan-dies-at-94.html

jazz

critic USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/

913619163/stanley-crouch-towering-jazz-critic-dead-at-74

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/16/

obituaries/stanley-crouch-dead.html

50 great moments in jazz

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog+series/

50-great-jazz-moments

Illustration:

Dante Zaballa

5 Minutes That

Will Make You Love Jazz Vocals

Nat King Cole,

Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong

were A-list

celebrities at the top of their art form.

Today’s jazz

singers are finding new paths.

Listen to these 11

favorites.

NYT

December 8, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/08/arts/music/jazz-vocals.html

free jazz USA

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/29/

717579612/more-than-kind-of-blue-in-1959-a-few-albums-changed-jazz-forever

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/23/

arts/music/bernard-stollman-record-label-founder-dies-at-85.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/23/

arts/music/ronald-shannon-jackson-avant-garde-drummer-dies-at-73.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/20/

arts/music/david-s-ware-adventurous-saxophonist-dies-at-62.html

free improvisation jazz UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/oct/03/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

Creed Taylor 1929-2022

USA

one of the most influential and prolific

jazz producers

of the second half of the last century,

best known for the distinctive work

he did for his CTI label in the 1970s,

(...)

Mr. Taylor began his career

as a jazz producer in the 1950s,

and in 1960 he founded the Impulse! label,

which would become the home of John Coltran

and other stars.

He did not stay there long, though,

and most of the label’s best-known records

were produced later.

He moved to another jazz label, Verve.

He made a lasting mark there

by producing recordings

by the saxophonist Stan Getz

that popularized bossa nova,

including “Getz/Gilberto,”

the celebrated 1964 album by Getz

and the guitarist João Gilberto

that included “The Girl From Ipanema,”

with Mr. Gilberto’s wife, Astrud.

Both the album and the single,

a crossover hit,

won Grammy Awards.

In 1967, Mr. Taylor was at A&M,

where he founded another label,

Creed Taylor Inc.,

better known as CTI.

Three years later

it became an independent label,

which over the next decade

became known for stylish albums

by George Benson, Stanley Turrentine,

Grover Washington Jr. and others

— and for a degree of commercial success

that was unusual for jazz.

“In many ways the sound of the 1970s

was defined by CTI,”

the musician and producer Leo Sidran said

in introducing a 2015 podcast

featuring an interview with Mr. Taylor.

The records Mr. Taylor released

on the label

often emphasized rhythm

and favored accessibility

over esoteric exploration.

As J.D. Considine wrote

in The New York Times in 2002

when some of these recordings

were rereleased,

Mr. Taylor “believed that jazz,

having started out as popular music,

ought to maintain a connection

to a broader audience.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/

arts/music/creed-taylor-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/

arts/music/creed-taylor-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2022/08/25/

1119337612/creed-taylor-legendary-producer-who-guided-and-expanded-jazz-dead-at-93

fusion USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/02/11/

967082282/chick-corea-jazz-fusion-pioneer-has-died-of-cancer-at-79

http://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2017/02/20/

516245069/guitarist-larry-coryell-godfather-of-fusion-dies-at-73

1959 >

Ornette Coleman's “The Shape of Jazz to Come”

USA

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/

story.php?storyId=6449431 - November 13,

2006

the original Dixieland Jazz Band

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/07/04/

arts/music-original-dixieland-jazz-band.html

The William P. Gottlieb Collection

USA

over sixteen hundred photographs

of celebrated jazz artists jazz scene

from 1938 to 1948,

primarily in New York City

and Washington, D.C.

https://www.loc.gov/collections/

jazz-photography-of-william-p-gottlieb/about-this-collection/

label > Strata-East Records - founded in 1971

About 50 years ago,

pianist Stanley Cowell and trumpeter Charles Tolliver

embarked on a bold venture together.

In the face of a tough business climate,

at a time of constriction in the record industry,

they started their own label, Strata-East Records,

breaking in its catalog with the self-titled debut

by their own working band, Music Inc.

More than just an indie record label,

Strata-East was one of the first artist-driven collectives;

ownership of the music remained

with the composer or bandleader.

It was a revolutionary model at the time

(and still hardly the norm today),

and appealed to a range of Black creative artists,

from saxophonist Clifford Jordan to poet Gil Scott-Heron

and keyboardist Brian Jackson,

whose 1974 album Winter in America

brought Strata-East a breakout hit.

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/03/

1060933094/strata-east-at-50-

how-a-revolutionary-record-label-put-control-in-artists-hands

indie jazz and blues label Delmark Records >

Bob

Koester 1932-2021

USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/15/

997105714/remembering-delmark-records-founder-bob-koester

Franklin Swan Driggs USA 1930-2011

writer, historian and record producer

who amassed what is considered

the finest collection of jazz photographs in the

world USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/26/

arts/music/frank-driggs-jazz-age-historian-and-photo-collector-dies-at-81.html

John Philip William Dankworth

musician, composer and bandleader UK 1927-2010 UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2010/feb/07/

sir-john-dankworth-obituary

William James Claxton USA 1927-2008 UK/USA

jazz photographer

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/oct/13/

william-claxton-photographer-chet-baker

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/oct/17/

jazz-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/oct/15/jazz

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2008/oct/15/

photography-art?picture=338596323

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/14/

arts/design/14claxton.html

https://www.npr.org/2008/10/18/

95827792/william-claxton-80-shot-jazz-for-the-eyes

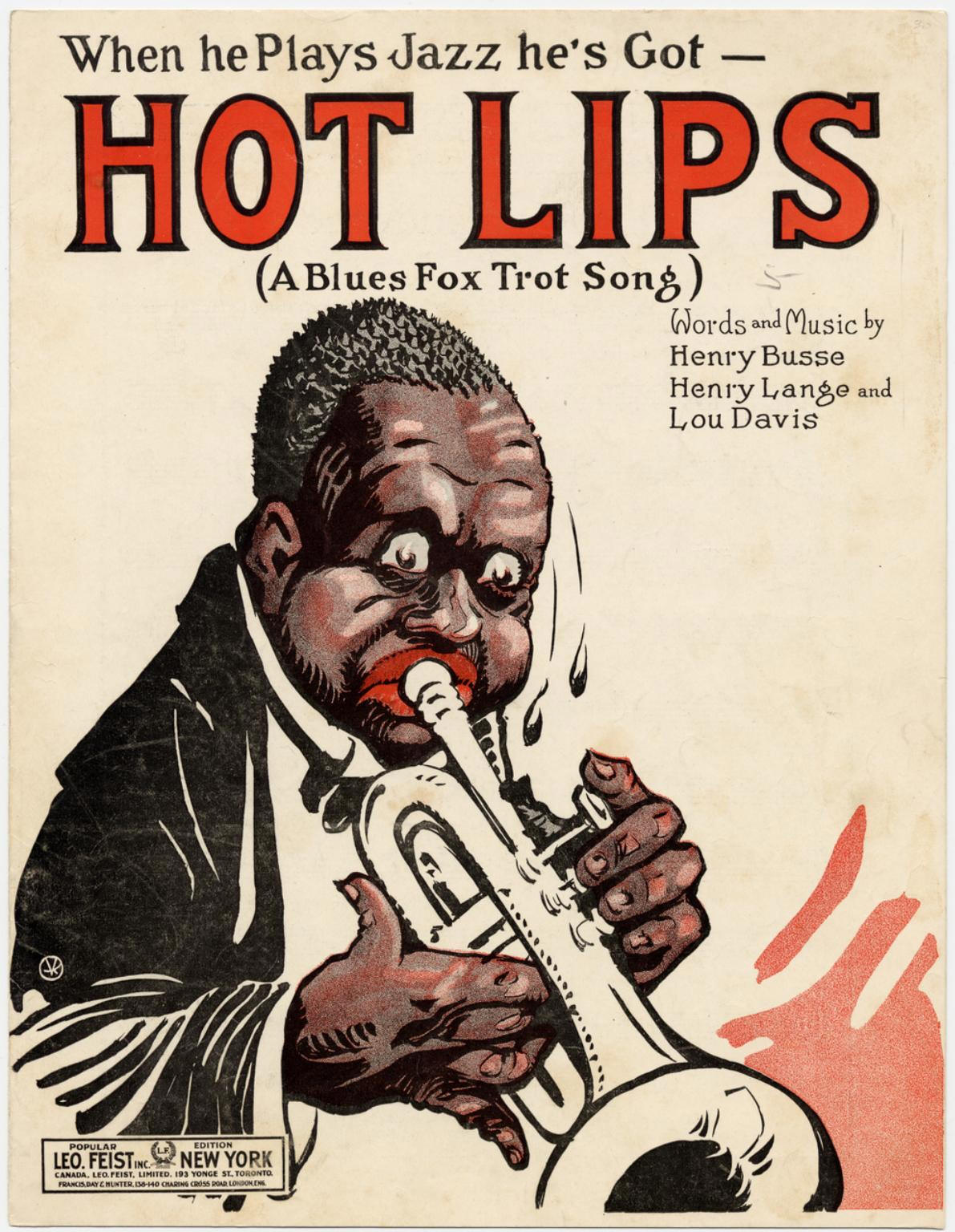

sheet music collection

1920s > popular American music

> UCLA Library USA

Sheet music from the UCLA Music Library’s

Archive of Popular American Music

https://digital.library.ucla.edu/sheetmusic/

Francis Wolff

1907/1908-1971

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Francis_Wolff

big band

bandleader

jazz quartet > Modern Jazz Quartet

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/29/

arts/music/29heath.html

swing UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2009/apr/27/

benny-goodman-jazz

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2009/feb/10/

louis-armstrong-invention-swing-jazz

swing USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/13/

arts/music/buddy-greco-singer-who-had-that-swing-dies-at-90.html

jive talk > glossary USA

Jive talk, Harlem jive or simply Jive

(also known as the argot of jazz, jazz jargon,

vernacular of the jazz world,

slang of jazz, and parlance of hip)

is an African-American Vernacular English slang

or vocabulary that developed in Harlem,

where "jive" (jazz) was played

and was adopted more widely in African-American society,

peaking in the 1940s.

- Wikipedia - August 26, 2022

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_jive_talk

jiving

cool USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/15/

835634362/lee-konitz-prolific-and-influential-jazz-saxophonist-has-died-at-92

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/29/

717579612/more-than-kind-of-blue-in-1959-a-few-albums-changed-jazz-forever

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/13/

fashion/mens-style/miles-davis-style-icon.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birth_of_the_Cool

bebop UK / USA

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/29/

717579612/more-than-kind-of-blue-in-1959-a-few-albums-changed-jazz-forever

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/04/

t-magazine/mintons-jazz-club-harlem-bebop.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/10/

556842176/after-midnight-thelonious-monk-at-100

http://www.npr.org/2016/08/22/

490940271/toots-thielemans-jazz-harmonica-baron-has-died

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2009/jul/06/

50-moments-jazz-bebop

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/18/

guardianobituaries.obituaries

bebop drummer > USA > Max Roach 1924-2007

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/20/

guardianobituaries.usa

hard bop USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/03/01/

972507165/ralph-peterson-jr-drummer-who-re-enlivened-hard-bop-dead-at-58

http://www.npr.org/event/music/

561069637/louis-hayes-80th-birthday-at-dizzy-s - Nov. 3, 2017

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/15/

arts/music/joe-sample-crusaders-pianist-dies-at-75.html

http://www.npr.org/2014/06/20/

323950913/remembering-horace-silver-hard-bop-pioneer

http://www.npr.org/2010/01/25/

99865218/a-hard-look-at-hard-bop

Illustration: Dante Zaballa

5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Ornette Coleman

We asked writers, critics and musicians

including Kamasi Washington, Nubya Garcia and Shabaka

Hutchings

to tell us how they connect with Coleman’s fearless artistry.

NYT

Nov. 2, 2022, 5:00 a.m. ET

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/02/

arts/music/ornette-coleman-jazz-music.html

saxophone player / saxophonist UK /

USA

https://www.theguardian.com/music/article/2024/may/14/

david-sanborn-jazz-saxophonist-dies-aged-78

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/02/

arts/music/ornette-coleman-jazz-music.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/20/

arts/music/david-s-ware-adventurous-saxophonist-dies-at-62.html

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/apr/03/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries2

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/oct/03/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

alto saxophone

alto saxophonist USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/13/

986501724/sonny-simmons-fiercely-independent-alto-saxophonist-dies-at-87

https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/15/

835634362/lee-konitz-prolific-and-influential-jazz-saxophonist-has-died-at-92

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/23/

arts/pop-music-the-return-of-jazz-s-greatest-eccentric.html

tenor-saxophone

combo

jazz trumpet USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/09/

arts/music/al-porcino-king-of-the-high-notes-on-jazz-trumpet-dies-at-88.html

jazz trumpeter USA

http://www.npr.org/2017/02/24/

517042756/jazz-on-film-and-the-problem-of-the-mad-creative-genius

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/23/

arts/music/clark-terry-influential-jazz-trumpeter-dies-at-94.html

https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/

january-06/

cornet USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/03/09/

1085637403/ron-miles-cornetist-who-imbued-modern-jazz-with-heart-and-soul-dies-at-58

cornetist

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/03/09/

1085637403/ron-miles-cornetist-who-imbued-modern-jazz-with-heart-and-soul-dies-at-58

flugelhorn USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/23/

arts/music/clark-terry-influential-jazz-trumpeter-dies-at-94.html

jazz clarinettist USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/28/

arts/music/joe-muranyi-clarinetist-with-louis-armstrong-dies-at-84.html

jazz organist UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/feb/11/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

jazz guitarist >

Larry Coryell USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2017/02/20/

516245069/guitarist-larry-coryell-godfather-of-fusion-dies-at-73

jazz instruments

bass

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/01/

arts/music/jazz-bass-music.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/08/28/

435576837/all-about-that-bass-but-give-the-drummer-some

bassist

UK / USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/12/

arts/music/charlie-haden-influential-jazz-bassist-is-dead-at-76.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2005/may/05/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

clarinettist

saxophonist

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/apr/03/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries2

alto saxophonist >

Clifford Everett "Bud" Shank

Jnr USA 1926-2009

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/apr/06/

bud-shank-obituary

trumpeter

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2004/jan/02/

jazz.shopping

hard-bop trumpeter > Clifford Brown

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2005/apr/15/

jazz.shopping1

trombone

> trombonist > Grachan Moncur III 1937-2022

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/06/03/

1103013844/grachan-moncur-iii-trailblazing-blue-note-trombonist-

dies-at-85

alto-saxist > Steve Coleman

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/apr/28/

jazz.shopping1

flutist > Samuel Most 1930-2013

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/23/

arts/sam-most-who-helped-bring-the-flute-into-the-jazz-mainstream-

dies-at-82.html

drums

snare drum

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/27/

arts/music/27jazz.html

kick drum

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/27/

arts/music/27jazz.html

ride cymbal

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/27/

arts/music/27jazz.html

drummer UK / USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/03/01/

972507165/ralph-peterson-jr-drummer-who-re-enlivened-hard-bop-

dead-at-58

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/23/

arts/music/ronald-shannon-jackson-avant-garde-drummer-

dies-at-73.html

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2009/jun/26/

paul-motian-trio

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2009/feb/18/

louie-bellson-obituary

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/20/

guardianobituaries.usa

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/18/

guardianobituaries.obituaries

https://www.nytimes.com/1974/04/13/

archives/2-young-drummers-lead-jazz-combos.html

Illustration:

Dante Zaballa

Five Minutes That

Will Make You Love Duke Ellington

We asked jazz

musicians, writers and others

to tell us what moves them.

Listen to their

choices.

NYT

Aug. 3, 2022

5:00 a.m. ET

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/03/

arts/music/duke-ellington-jazz-music.html

piano

Harlem stride piano > James P. Johnson

USA

http://video.nytimes.com/video/2009/10/06/nyregion/1247465020527/

flowers-for-a-jazzman-s-unmarked-grave.html

jazz pîanist

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/11/28/

1139388807/pianist-ahmad-jamal-has-released-a-pair-of-archival-albums

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/03/

arts/music/duke-ellington-jazz-music.html

https://www.npr.org/2020/03/06/

812954365/mccoy-tyner-the-pianist

https://www.npr.org/2020/03/06/

812940062/mccoy-tyner-groundbreaking-pianist-of-20th-century-jazz-dies-at-81

http://www.npr.org/2014/06/20/

323950913/remembering-horace-silver-hard-bop-pioneer

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/

arts/music/mulgrew-miller-jazz-pianist-dies-at-57.html

hard bop pianist > Sonny Clark USA 1931-1963

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonny_Clark

https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/18/

arts/the-pop-life-recalling-sonny-clark.html

pianist > Canada > Oscar Emmanuel Peterson 1925-2007

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2007/dec/25/2

http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/news/2007-12-24-

oscar-peterson_N.htm

flautist >

Clifford Everett "Bud" Shank Jnr

USA 1926-2009

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/apr/06/

bud-shank-obituary

Benjamin Gordon Powell Jr. USA 1930-2010

Trombonist who performed or recorded

with everyone from Frank Sinatra to

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins

but who was best known

for his long tenure with Count Basie’s big band

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/04/

arts/music/04powell.html

trombonist >

Weldon Leo "Jack" Teagarden USA 1905-1964 UK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Jack_Teagarden

USA >

vibraphone UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/jun/19/

how-we-made-roy-ayers-everybody-loves-the-sunshine

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/06/

arts/music/vibraphone-jazz-music.html

vibraphonist USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/17/

arts/music/bobby-hutcherson-dies-jazz.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/21/

arts/music/teddy-charles-jazz-musician-turned-sea-captain-dies-at-84.html

vibraphone > USA > Lionel Hampton

UK

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/06/

arts/music/vibraphone-jazz-music.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/sep/01/

arts.artsnews

sideman

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/23/

obituaries/michael-henderson-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/

arts/music/idris-muhammad-drummer-whose-beat-still-echoes-

dies-at-74.html

harmonica

USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/08/22/

490940271/toots-thielemans-jazz-harmonica-baron-has-died

jazz harmonica

player USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/08/22/

490940271/toots-thielemans-jazz-harmonica-baron-has-died

The Lenox Lounge opened in Harlem in 1942

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/08/nyregion/

harlem-to-say-goodbye-to-the-lenox-lounge.html

jam session

tour

swing

tap dancer

Charleston dance

American black music

gospel USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/28/

arts/music/fontella-bass-72-singer-of-rescue-me-is-dead.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/22/

arts/music/inez-andrews-gospel-singer-dies-at-83.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/27/

arts/music/jessy-dixon-gospel-singer-and-songwriter-dies-at-73.html

gospel group > The Staple Singers 1950's-1960's

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/apr/15/

popandrock.urban

secular music USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/28/

arts/music/fontella-bass-72-singer-of-rescue-me-is-dead.html

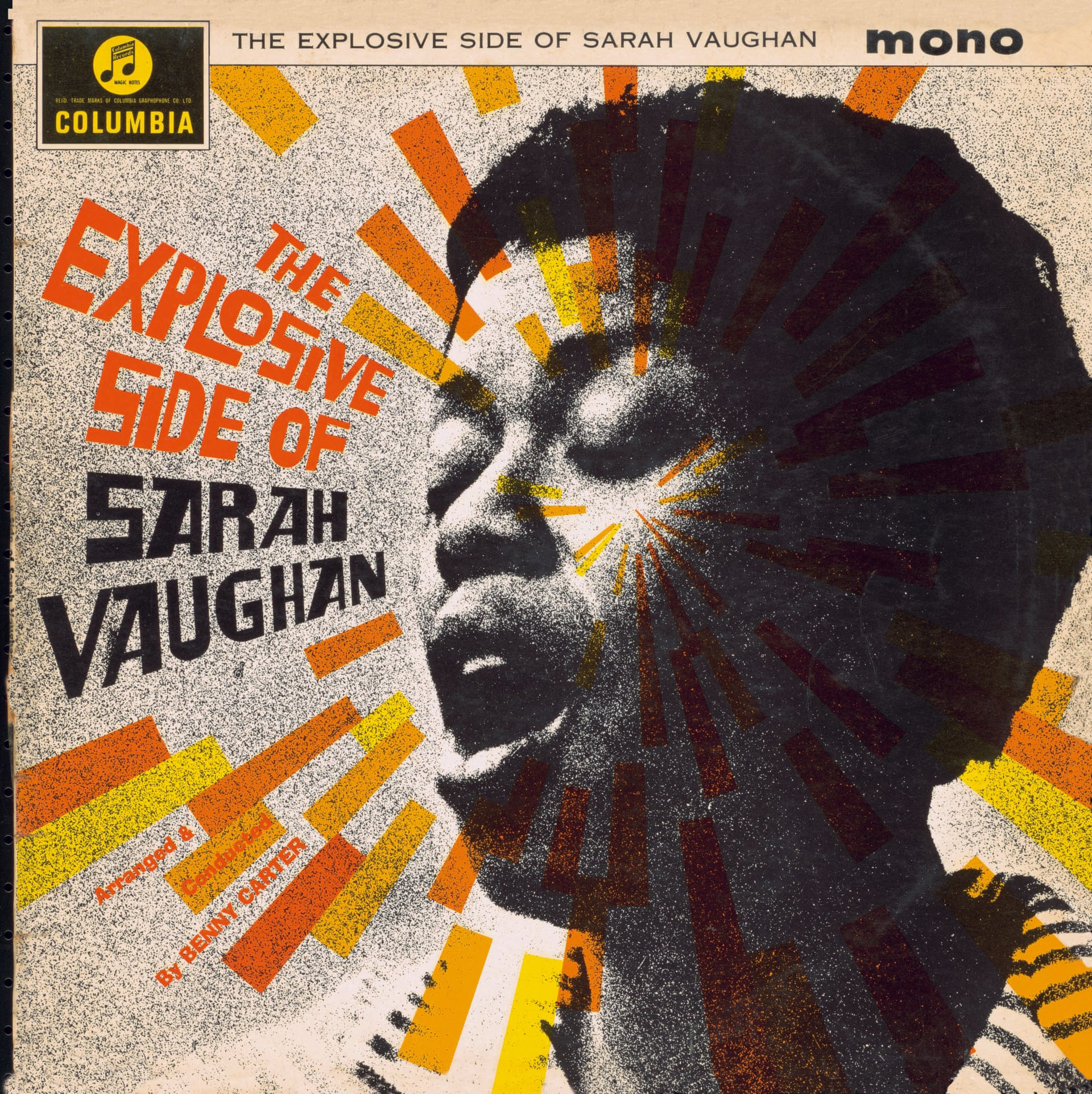

Sarah Vaughan – The Explosive Side of ...

Released by Columbia in 1963

Photograph: Taschen

And all that jazz:

innovative album covers from the 1950s on –

in pictures

In a new Taschen book Jazz Covers,

a range of striking and colourful album artworks

showcase a long-running relationship

between the worlds of

design and jazz music,

from Archie Shepp to Duke Ellington

G

Fri 16 Apr 2021 15.01 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2021/apr/16/

jazz-albums-artists-covers-taschen-in-pictures

USA >

jazz covers UK

https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2021/apr/16/

jazz-albums-artists-covers-taschen-in-pictures

jazz covers > Sadamitsu Fujita USA 1921-2010

graphic designer

who used avant-garde painting and photography

to create some of the most striking album covers of the 1950s,

and who designed the visually arresting book jackets

for “In Cold Blood” and

“The Godfather”

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/27/

arts/design/27fujita.html

USA > soul / R&B

label > Motown Records UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/music/

motown

http://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2017/08/30/

547029912/stevie-wonder-reflects-on-motown-god-and-prince

http://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2017/04/19/

524716502/remembering-sylvia-moy-pioneering-motown-songwriter-and-producer

http://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2016/mar/29/

motown-the-sound-of-young-america-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/mar/22/

how-we-made-motown-records-

berry-gordy-smokey-robinson-stevie-wonder-interview

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/dec/13/

motown-maps-sites-legendary-detroit-label

USA >

jazz label > Verve Records > Norman Granz

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/oct/27/

verve-records-jazz-norman-granz

http://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2013/oct/27/

verve-records-norman-granz-jazz

Title : Hot lips

Creators : Lange, Henry [composer/lyricist]

: Busse, Henry [composer/lyricist]

: Davis, Louis [composer/lyricist]

Publisher : New York : Leo. Feist, Inc.

Date : 1922

Tempo : Allegro moderato

Key : F Major, A flat Major

https://digital.library.ucla.edu/sheetmusic/

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Music

Gospel, Doo Wop, Blues,

Jazz, Fusion

Monk’s Moods

October 18, 2009

The New York Times

By AUGUST KLEINZAHLER

THELONIOUS MONK

The Life and Times of an American Original

By Robin D. G. Kelley

Illustrated. 588 pp. Free Press. $30

Thelonious Monk, the great American jazz artist, during the first half of his

junior year at Stuyvesant High School in New York, showed up in class only 16

out of 92 days and received zeros in every one of his subjects. His mother,

Barbara Monk, would not have been pleased. She had brought her three children to

New York from North Carolina, effectively leaving behind her husband, who

suffered bad health, and raising the family on her own, in order that they might

receive a proper education. But Mrs. Monk, like a succession of canny,

tough-minded, loving and very indulgent women in Thelonious Monk’s life,

understood that her middle child had a large gift and was put on this earth to

play piano. Presently, her son was off on a two-year musical tour of the United

States, playing a kind of sanctified R & B piano in the employ, with the rest of

his small band, of a traveling woman evangelist.

The brilliant pianist Mary Lou Williams, seven years Monk’s senior and working

at the time for Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy orchestra, heard Monk play at a

late-night jam session in Kansas City in 1935. Monk, born in 1917, would have

been 18 or so at the time. When not playing to the faithful, he sought out the

musical action in centers like Kansas City. Williams would later claim that even

as a teenager, Monk “really used to blow on piano. . . . He was one of the

original modernists all right, playing pretty much the same harmonies then that

he’s playing now.”

It was those harmonies — with their radical, often dissonant chord voicings,

along with the complex rhythms, “misplaced” accents, startling shifts in

dynamics, hesitations and silences — that, even in embryonic form, Williams was

hearing for the first time. It’s an angular, splintered sound, percussive in

attack and asymmetrical, music that always manages to swing hard and respect the

melody. Monk was big on melody. Thelonious Monk’s body of work, as composer and

player (the jazz critic Whitney Balliett called Monk’s compositions “frozen . .

. improvisations” and his improvisations “molten . . . compositions”), sits as

comfortably beside Bartok’s Hungarian folk-influenced compositions for solo

piano as it does beside the music of jazz giants like James P. Johnson, Teddy

Wilson and Duke Ellington, some of the more obvious influences on Monk. It’s

unclear how much of Bartok he listened to. Monk did know well and play

Rachmaninoff, Liszt and Chopin (especially Chopin). Stravinsky was also a

favorite.

Robin D. G. Kelley, in his extraordinary and heroically detailed new biography,

“Thelonious Monk,” makes a large point time and time again that Monk was no

primitive, as so many have characterized him. At the age of 11, he was taught by

Simon Wolf, an Austrian émigré who had studied under the concertmaster for the

New York Philharmonic. Wolf told the parent of another student, after not too

many sessions with young Thelonious: “I don’t think there will be anything I can

teach him. He will go beyond me very soon.” But the direction the boy would go

in, after two years of classical lessons, was jazz.

Monk was well enough known and appreciated in his lifetime to have appeared on

the cover of the Feb. 28, 1964, issue of Time magazine. He was 46 at the time,

and after many years of neglect and scuffling had become one of the principal

faces and sounds of contemporary jazz. The Time article, by Barry Farrell, is,

given the vintage and target audience, well done, both positive and fair, and

accurate in the main. But it does make much of its subject’s eccentricities, and

refers to Monk’s considerable and erratic drug and alcohol use. This last would

have raised eyebrows in the white middle-class America of that era.

Throughout the book, Kelley plays down Monk’s “weirdness,” or at least

contextualizes it. But Monk did little to discourage the popular view of him as

odd. Always a sharp dresser and stickler for just the right look, he also

favored a wide array of unconventional headgear: astrakhan, Japanese skullcap,

Stetson, tam-o’-shanter. He had a trickster sense of humor, in life and in

music, and he loved keeping people off-balance in both realms. Off-balance was

the plane on which Monk existed. He also liked to dance during group

performances, but this served very real functions: first, as a method of

conducting, communicating musical instructions to the band members; and second,

to let them know that he dug their playing when they were in a groove and

swinging.

Even early in his career, Monk often insisted on showing up late to gigs,

driving bandleaders, club owners and audiences to distraction. And on occasion

he would simply fall asleep at the piano. He would also disappear to his room in

the family apartment for two weeks at a time. When he was young, these behaviors

or idiosyncrasies were tolerated and, more or less, manageable. But the manic,

erratic behavior turned out to be the precursor of a more serious bipolar

illness that would over time become immobilizing. From his father, Thelonious

Sr., who was gone from the scene by the time Monk was 11, Thelonious Jr. seems

to have gotten his musical gene (there always seems to be one in there). But he

also inherited his father’s illness. Monk Sr. was committed to the State

Hospital for the Colored Insane in Goldsboro, N.C., at the age of 52, in 1941.

He never left.

Kelley, the author of “Race Rebels” and other books, makes use of the “carpet

bombing” method in this biography. It is not pretty, or terribly selective, but

it is thorough and hugely effective. He knows music, especially Monk’s music,

and his descriptions of assorted studio and live dates, along with what Monk is

up to musically throughout, are handled expertly. The familiar episodes of

Monk’s career are all well covered: the years as house pianist at Minton’s

after-hours club in Harlem, which served as an incubator for the new “modern

music,” later to be called bebop; the brilliant “Genius of Modern Music”

sessions for Blue Note, Monk’s first recordings with him as the bandleader; the

drug bust, where Monk took the rap for Bud Powell and lost his New York cabaret

license for six years; his triumphant return in 1957 with his quartet, featuring

John Coltrane, at the Five Spot; the terrible beating Monk took for resisting

arrest in New Castle, Del.; the final dissolution and breakdown. Likewise, the

characters in Monk’s life and career are well served: his fellow musicians; his

family; his friend and benefactor, the fascinating Pannonica (Nica) de

Koenigswarter, the “jazz baroness,” at whose home in Weehawken, N.J., Monk spent

his final years. He would die, after a long silence, in 1982, in the arms of his

wife, Nellie.

Musicians — particularly jazz musicians of Monk’s period, and most especially

Monk, taciturn and gnomic in utterance by nature — tend not, as writers do, to

write hundreds of letters sharing with intimates what is going on in their

hearts or heads. A biography of Monk, perforce, has to rely on the not always

reliable, often conflicting, memories of others. Instinct is involved, surely as

much as perspicacity, in sifting through the mass of observation and anecdote.

The Monk family appears to have shared private material with Kelley that had

hitherto been unavailable. This trust was not misplaced. There will be shapelier

and more elegantly written biographies to come — Monk, the man and the music, is

an endlessly fascinating subject — but I doubt there will be a biography anytime

soon that is as textured, thorough and knowing as Kelley’s. The “genius of

modern music” has gotten the passionate, and compassionate, advocate he

deserves. h

August Kleinzahler’s most recent book

is

“Music: I-LXXIV,” a collection of

essays.

Monk’s Moods,

NYT,

16.10.2009,

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/18/

books/review/Kleinzahler-t.html

Freddie Hubbard,

Jazz Trumpeter,

Dies at 70

December 30, 2008

The New York Times

By PETER KEEPNEWS

Freddie Hubbard, a jazz trumpeter who dazzled audiences and critics alike

with his virtuosity, his melodicism and his infectious energy, died on Monday in

Sherman Oaks, Calif. He was 70 and lived in Sherman Oaks.

The cause was complications of a heart attack he had on Nov. 26, said his

spokesman, Don Lucoff of DL Media.

Over a career that began in the late 1950s, Mr. Hubbard earned both critical

praise and commercial success — although rarely for the same projects.

He attracted attention in the 1960s for his bravura work as a member of the Jazz

Messengers, the valuable training ground for young musicians led by the veteran

drummer Art Blakey, and on albums by Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and many

others. He also recorded several well-regarded albums as a leader. And although

he was not an avant-gardist by temperament, he participated in three of the

seminal recordings of the 1960s jazz avant-garde: Ornette Coleman’s “Free Jazz”

(1960), Eric Dolphy’s “Out to Lunch” (1964) and John Coltrane’s “Ascension”

(1965).

In the 1970s Mr. Hubbard, like many other jazz musicians of his generation,

began courting a larger audience, with albums that featured electric

instruments, rock and funk rhythms, string arrangements and repertory sprinkled

with pop and R&B songs like Paul McCartney’s “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” and

the Stylistics’ “Betcha by Golly, Wow.” His audience did indeed grow, but his

standing in the jazz world diminished.

By the start of the next decade he had largely abandoned his more commercial

approach and returned to his jazz roots. But his career came to a virtual halt

in 1992 when he damaged his lip, and although he resumed performing and

recording after an extended hiatus, he was never again as powerful a player as

he had been in his prime.

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard was born on April 7, 1938, in Indianapolis. His first

instrument was the alto-brass mellophone, and in high school he studied French

horn and tuba as well as trumpet. After taking lessons with Max Woodbury, the

first trumpeter of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, at the Arthur Jordan

Conservatory of Music, he performed locally with, among others, the guitarist

Wes Montgomery and his brothers.

Mr. Hubbard moved to New York in 1958 and almost immediately began working with

groups led by the saxophonist Sonny Rollins, the drummer Philly Joe Jones and

others. His profile rose in 1960 when he joined the roster of Blue Note, a

leading jazz label; it rose further the next year when he was hired by Blakey,

widely regarded as the music’s premier talent scout.

Adding his own spin to a style informed by Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and

Clifford Brown, Mr. Hubbard played trumpet with an unusual mix of melodic

inventiveness and technical razzle-dazzle. The critics took notice. Leonard

Feather called him “one of the most skilled, original and forceful trumpeters of

the ’60s.”

After leaving Blakey’s band in 1964, Mr. Hubbard worked for a while with another

drummer-bandleader, Max Roach, before forming his own group in 1966. Four years

later he began recording for CTI, a record company that would soon become known

for its aggressive efforts to market jazz musicians beyond the confines of the

jazz audience.

His first albums for the label, notably “Red Clay,” contained some of the best

playing of his career and, except for slicker production and the presence of

some electric instruments, were not significantly different from his work for

Blue Note. But his later albums on CTI, and the ones he made after leaving the

label for Columbia in 1974, put less and less emphasis on improvisation and

relied more and more on glossy arrangements and pop appeal. They sold well, for

the most part, but were attacked, or in some cases simply ignored, by jazz

critics. Within a few years Mr. Hubbard was expressing regrets about his career

path.

Most of his recordings as a leader from the early 1980s on, for Pablo,

Musicmasters and other labels, were small-group sessions emphasizing his gifts

as an improviser that helped restore his critical reputation. But in 1992 he

suffered a setback from which he never fully recovered.

By Mr. Hubbard’s own account, he seriously injured his upper lip that year by

playing too hard, without warming up, once too often. The lip became infected,

and for the rest of his life it was a struggle for him to play with his

trademark strength and fire. As Howard Mandel explained in a 2008 Down Beat

article, “His ability to project and hold a clear tone was damaged, so his fast

finger flurries often result in blurts and blurs rather than explosive phrases.”

Mr. Hubbard nonetheless continued to perform and record sporadically, primarily

on fluegelhorn rather than on the more demanding trumpet. In his last years he

worked mostly with the trumpeter David Weiss, who featured Mr. Hubbard as a

guest artist with his group, the New Jazz Composers Octet, on albums released

under Mr. Hubbard’s name in 2001 and 2008, and at occasional nightclub

engagements.

Mr. Hubbard won a Grammy Award for the album “First Light” in 1972 and was named

a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2006.

He is survived by his wife of 35 years, Briggie Hubbard, and his son, Duane.

Mr. Hubbard was once known as the brashest of jazzmen, but his personality as

well as his music mellowed in the wake of his lip problems. In a 1995 interview

with Fred Shuster of Down Beat, he offered some sober advice to younger

musicians: “Don’t make the mistake I made of not taking care of myself. Please,

keep your chops cool and don’t overblow.”

Freddie Hubbard, Jazz

Trumpeter, Dies at 70,

NYT,

29.12.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/30/

arts/music/30hubbard.html

Saxophonist Johnny Griffin

Dies at 80

July 26,

2008

The New York Times

By BEN RATLIFF

Johnny

Griffin, a jazz tenor-saxophonist from Chicago whose speed, control, and

harmonic acuity made him one of the most talented musicians of his generation,

and who abandoned his hopes for an American career when he moved to Europe in

1963, died Friday at his home in Availles-Limouzine, a village in France. He was

80 and had lived in Availles-Limouzine for 24 years.

His death was announced to Agence France-Presse by his wife, Miriam, who did not

give a cause. He played his last concert Monday in Hyères.

His height — around five feet five — earned him the nickname “The Little Giant”;

his speed in bebop improvising marked him as “The Fastest Gun in the West”; a

group he led with Eddie Lockjaw Davis was informally called the “tough tenor”

band, a designation that was eventually applied to a whole school of hard bop

tenor players.

And in general, Mr. Griffin suffered from categorization. In the early 1960s, he

became embittered by the acceptance of free jazz; he stayed true to his identity

as a bebopper. When he felt the American jazz marketplace had no use for him (at

a time he was also having marital and tax troubles) , he left for Holland.

At that point America lost one of its best musicians, even if his style fell out

of sync with the times.

“It’s not like I’m looking to prove anything any more,” he said in a 1993

interview. “At this age, what can I prove? I’m concentrating more on the beauty

in the music, the humanity.”

Indeed his work in the 1990s, with an American quartet that stayed constant

whenever he revisited his home country to perform or record, had a new sound,

mellower and sweeter than in his younger days.

Mr. Griffin grew up on the South Side of Chicago and attended DuSable High

School, where he was taught by the high school band instructor Capt. Walter

Dyett, who also taught the singers Nat (King) Cole and Dinah Washington and the

saxophonists Gene Ammons and Von Freeman.

Mr. Griffin’s career started in a hurry: At the age of 12, attending his grammar

school graduation dance at the Parkway ballroom, he saw Ammons play in King

Kolax’s big band and decided what his instrument would be. By 14, he was playing

alto saxophone in a variety of situations, including a group called the Baby

Band with schoolmates, and occasionally with the guitarist T-Bone Walker.

At 18, three days after his high school graduation, Mr. Griffin left Chicago to

join Lionel Hampton’s big band, switching to tenor saxophone. From then until

1951, he was mostly on the road, though based in New York City. By 1947 he was

touring with Joe Morris, a fellow Chicagoan who ran a rhythm-and-blues band, and

with Morris he made his first recordings for the Atlantic record label. He

entered the army in 1951, was stationed in Hawaii, and played in an army band.

Mr. Griffin was of an impressionable age when Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

became a force in jazz. He heard both with the Billy Eckstine band in 1945;

having first internalized the more ballad-like saxophone sound earlier

popularized by Johnny Hodges and Ben Webster, he was now entranced by the

lightning-fast phrasing of the new music, bebop. In general, his style remained

brisk but relaxed, his bebop playing salted with blues tonality.

Beyond the 1960s, his skill and his musical eccentricity continued to deepen,

and in later years he could play odd, asymmetrical phrases, bulging with blues

honking and then tapering off into state-of-the-art bebop, filled with passing

chords.

Starting in the late 1940s, he befriended the pianists Elmo Hope, Bud Powell and

Thelonious Monk, and he called these friendships his “postgraduate education.”

After his army service, he went back to Chicago and started playing with Monk, a

move that altered his career. He became interested in Monk’s brightly melodic

style of composition, and he ended up as a regular member of Monk’s quartet back

in New York in the late ‘50s; later, in 1967, he played with Monk’s touring

eight- and nine-person groups.

In 1957, Mr. Griffin joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers for a short stint, and

in 1958 started making his own records for the Riverside label. On a series of

recordings, including “Way Out” and “The Little Giant,” his rampaging energy got

its moment in the sun: on tunes like “Cherokee,” famous vehicles to test a

musician’s mettle, he was simply blazing.

A few years later he hooked up with Eddie Lockjaw Davis, a more blues-oriented

tenor saxophonist, and made a series of records that act as barometers of taste:

listeners tend to either find them thrilling or filled with too many notes,

especially on Monk tunes. The matchup with Davis was a popular one, and they

would sporadically reunite through the ‘70s and ‘80s.

In 1963 he left the United States, eventually settling in Paris and recording

thereafter mostly for European labels — sometimes with other American

expatriates like Kenny Clarke, sometimes with European rhythm sections. In 1973

he moved to Bergambacht, in the Netherlands; in the early 80s he moved to

Poitiers, in southwestern France.

With his American quartet — including the pianist Michael Weiss and the drummer

Kenny Washington — he stayed true to the bebop small-group ideal, and the 1991

record he made with the group for the Antilles label, called “The Cat,” was

received warmly as a comeback.

Every April he returned to Chicago to visit family and play during his birthday

week at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago, and usually spent a week at the Village

Vanguard in New York before returning home to his quiet countryside chateau.

Saxophonist Johnny Griffin Dies at 80,

NYT,

26.7.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/26/

arts/music/26griffin.html

Max Roach Is Remembered

for Music and More

August 25, 2007

The New York Times

By PETER KEEPNEWS

Max Roach was remembered at his funeral not just as a brilliant drummer who

helped bring about radical changes in American music, but also as a committed

activist who worked hard to bring about radical changes in American society.

Mr. Roach “used his music as an instrument of our struggle,” the Rev. Calvin O.

Butts III of Abyssinian Baptist Church said in eulogizing Mr. Roach, who died on

Aug. 16 at the age of 83. Mr. Roach’s funeral, held yesterday morning at

Riverside Church in Morningside Heights, drew a capacity crowd of friends,

admirers and fellow musicians.

Former President Bill Clinton, in a statement read by Representative Charles B.

Rangel, Democrat of New York, praised Mr. Roach as “one of the first jazz

musicians to align his craft with the goals of the civil rights movement.”

But Mr. Roach’s musical contributions were not neglected. The writer Amiri

Baraka, while noting that the music Mr. Roach and the singer Abbey Lincoln made

in the 1960s was “part of the liberation movement,” also read a poem that

included a long list of musicians who owed Mr. Roach an artistic debt. Bill

Cosby said that he owed Mr. Roach a different kind of debt — and that Mr. Roach

had owed him one, too.

“Why I became a comedian is because of Max Roach,” he said. “I wanted to be a

drummer.”

As a young jazz fan in Philadelphia, Mr. Cosby explained, he tried to teach

himself to play drums by copying records and watching the great jazz drummers in

action. But when he first saw Mr. Roach, he said, he was awed by his virtuosity

and realized that “there were no tricks, nothing I could take.”

Shortly thereafter, Mr. Cosby told the crowd, he decided that the rudimentary

drum kit for which he had paid $75 was not for him. And, he added, when he

finally met Mr. Roach some years later, the first thing he said to him was, “You

owe me $75.”

As befits a memorial for a man recognized as one of the architects of modern

jazz, music played an important part in the service. The vocalist Cassandra

Wilson, the pianists Randy Weston and Billy Taylor, and the saxophonist Jimmy

Heath were among those who performed.

Mr. Heath performed an unaccompanied improvisation on a song whose title

encapsulated what many of the speakers said about Mr. Roach: “There Will Never

Be Another You.”

Max Roach Is Remembered

for Music and More,

NYT,

25.8.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/25/

arts/music/25roach.html

Obituary

Max Roach

One of the great bebop drummers,

he went on to help define modern jazz

Saturday August 18, 2007

Guardian

Ronald Atkins

It says much for Charlie Parker's ability to spot talent that two young

sidemen from his most famous quintet, Miles Davis (obituary September 30, 1991)

and Max Roach, left him far behind. Roach, who has died aged 83, was rated among

the greatest of pioneering drummers and later shone as an innovative composer

and bandleader.

Parker brought an unprecedented rhythmic intensity to jazz, packing his solos

with phrases that used the gap between beats as a springboard. The underlying

pulse had quickened during the swing decade from two beats to four. Parker and

other bebop masters stretched it to eight in a bar. It followed that a

swing-style background guitar strumming would impede the soloists. So, strummers

were outlawed, which left more flexible, less intrusive bassists to combine

metric and harmonic roles.

Roach, barely 20 when he recorded Koko with Parker, reinvented the role of the

drums to exploit these changes. He had the imagination and the quickfire hands,

not merely to tap eight beats evenly on his top cymbal at speed but to elaborate

them or vary the tones. Bebop's doubling the number of beats created space that

encouraged the drummer to overlap between bars, and Roach did so with an endless

array of fill-ins and paradiddles. Inventiveness and technical dexterity were

equally balanced in his solos, which he built with impeccable logic.

Born in New Land, North Carolina, Roach was four when his family moved to New

York. His aunt was pianist in the local baptist church, where the young Max

sang. When he was eight, he began studying piano, when he was 12, his father

bought him a drum kit. He taught himself music and had a succession of gigs

while still at the boy's high school in Brooklyn. At 16 he briefly played with

Duke Ellington's orchestra. Later he studied theory and composition at the

Manhattan School of Music.

Roach's recording debut was with Coleman Hawkins in 1943 and he toured with

Benny Carter's big band. By 1945, firmly into bebop mode, he worked with Parker

and Dizzy Gillespie, appearing on all the Parker classics, from Koko to Billie's

Bounce and Parker's Mood. In 1949-50 he featured on Davis's Birth of the Cool

sessions.

In the early 1950s Roach gravitated to Los Angeles, working with west coast

musicians and appearing in the film Carmen Jones (1954). In the same year,

offered the chance to form a group, he recruited the superlative trumpeter

Clifford Brown into what became known as the Roach-Brown quintet. Brown's

saxophone partners were successively Teddy Edwards, Harold Land and Sonny

Rollins. Kenny Dorham joined after Brown was killed in a car crash. Brown's

death sent Roach into a profound, alcohol-fuelled depression, for which he

received psychiatric help. He also defeated a heroin habit.

Parker died in 1955, and modern jazz, via groups led by Davis, Art Blakey,

Horace Silver and others ironed out bebop's jagged edges. The first Roach

quintets fitted this pattern, though even then, the leader's tendency to pick

very fast tempos added an abrasiveness that became more marked when, after

Rollins and then Dorham left, he brought in younger men. Replacing the piano

with tuba or trombone pushed the drums further towards the front line.

After 1955, a radical tide inspired black Americans to focus on African culture.

Increasingly writing the material for his groups, Roach's contributions

intensified through an association with singer Abbey Lincoln - they later

married - and Lincoln introduced him to lyricist Oscar Brown Jr (obituary June

1, 2005). The three collaborated on the Freedom Now Suite (1960). Roach broke

entirely fresh ground with the album, It's Time, composing the music for a

16-piece choir and a jazz sextet, followed by the equally gripping Lift Every

Voice And Sing, made up of his arrangements of spirituals.

Among musicians who identified with black consciousness, Roach was most

frequently involved in direct action. Together with Charles Mingus - with whom

he had set up the shortlived Debut label in 1952 - he organised the Newport

Rebels concert, featuring musicians allegedly ignored by the main Newport

festival. Roach even interrupted a Miles Davis Carnegie Hall charity performance

because he disapproved of the beneficiary. The Village Vanguard club's owner

once pleaded with him to just play music and stop lecturing the audience.

In the 1980s, he set Martin Luther King Jr's I Have A Dream speech to a drum

accompaniment. His British appearances included a 1986 concert during Africa

Week. Its organisers, the then Greater London Council, named a Brixton park

after him.

Many young musicians he employed carved out their own niches. Among them were

trumpeter Booker Little and saxophonists Stanley Turrentine and George Coleman.

Little's partnership with the reedsman Eric Dolphy, a double-act that thrived on

extremes of emotional contrast, works to perfection on Tender Warriors, from

another classic Roach album, Percussion Bitter Suite. Their successors,

trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater and saxophonist Odean Pope, appeared in a number of

Roach's groups during a period of 20 years.

By then, jazz musicians were in demand for academic posts and in 1972, Roach had

begun a long association with the University of Massachusetts where he joined

the department of music and dance. His awards included an honorary doctorate in

music from the New England Conservatory. In 1988, he became the first jazz

musician to be given a MacArthur fellowship, reserved for those making major

contributions to American culture and science.

Roach outgrew the conventions of bebop to the extent that younger innovators

such as Anthony Braxton and Cecil Taylor played duets with him. He played his

last concert with Taylor at Colombia University in 2000. Never interested in

retracing his career, he continued to break fresh ground well into his 70s. He

was among the first jazz stars to claim rappers followed a black tradition by

making music without expensive instruments. In 1983 he shared the stage with a

team of breakdancers, a rapper and two DJs. He won an Obie for his music for

three Sam Shepard plays in 1984. He performed with symphony orchestras,

classical string quartets - in one of which his daughter Maxine played cello -

as well as with Japanese drummers and Chinese free improvisers, and composed

music for Alvin Ailey dance pieces. Perhaps the most telling long-term outcome

of his interest in Africa was the splendidly named M'Boom, first set up in the

early 1970s, an African-related percussion ensemble including marimba and

xylophone that incorporated jazz ideas. His last recording was with Clark Terry

in 2002.

Roach's three marriages ended in divorce. His survivors include a son and

daughter from his first marriage, a son from another relationship and twin

daughters from his third marriage.

· Maxwell Lemuel Roach, musician,

born January 10 1924; died August 16 2007

Max Roach,

G,

18.8.2007,

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/aug/18/

guardianobituaries.obituaries

From The Times Archives

On This Day - June 14, 1986

Benny Goodman was at one time

the

best-known musician in the US,

and was the first to play jazz

in Carnegie Hall,

New York

BENNY GOODMAN, one of the world’s greatest

jazz clarinettists and the first man to bring together blacks and whites in one

band, died from a heart attack at his Manhattan home yesterday. He was 77.

His body was found in his East Side apartment yesterday afternoon, said Mr Lloyd

Rausch, his personal assistant.

The “King of Swing”, who dominated jazz for 50 years, was raised in Chicago and

started playing in a synagogue when he was 13. He went on to become the first

person to play jazz in New York’s Carnegie Hall.

He had recently emerged from semi-retirement, and finding his sound and

techniques were still good, formed a new band last year and began accepting

engagements.

He brought blacks into his band in the 1930s, using the piano of Teddy Wilson

and the vibes of Lionel Hampton.

“He was really a great man, a godsend to the world,” Mr Wilson said yesterday.

“We’ve lost another giant,” said big band leader Ray Anthony.

A blunt, grumpy man who was not afraid to call rock‘n’roll “amplified junk”, he

made numerous recordings and was known throughout the world.

Ronnie Scott paid tribute to Goodman last night. “You cannot overestimate his

talent, he was one of the greats.

“He was known as a hard man to work with and was famous for the glare he would

give people when they did something he did not like.

“As a musician he was hard to fault and to me was the greatest jazz clarinet

player of all time,” he said.

From

The Times Archives >

On This Day - June 14, 1986,

Ts,

14.6.2005,

http://www.newsint-archive.co.uk/

pages/main.asp - broken link

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

music > genre > jazz > record labels >

Blue Note

music > genre > rap, hip-hop

music > genre > soul

music > genre

> blues

slavery,

eugenics,

race relations,

racial divide, racism,

segregation, civil rights,

apartheid

African-Americans > NYC > Harlem

Related > Anglonautes >

Arts >

Music

urban

music, rap, hip-hop

jazz

blues

soul

Related > Anglonautes >

History

20th century > USA > Civil rights

17th, 18th, 19th, 20th century

English America, America, USA

Racism,

Slavery,

Abolition, Civil war,

Abraham Lincoln,

Reconstruction

17th, 18th, 19th century

English America, America, USA

|