|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Architecture, Cities > Suburbs

Bushland, a suburb of Amarillo.

Photograph: Damon Winter

Gerrymander U.S.A.

NYT

July 12, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/12/

opinion/texas-redistricting-maps-gerrymandering.html

Untitled Arizona IV

by Christoph Gielen

Can Paradise Be Planned?

NYT

APRIL 18, 2014

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/19/

opinion/can-paradise-be-planned.html

Suburban housing

estates seen from the air

in Queensbury, north-west London in 1935.

Photograph: RH

Windsor

Getty

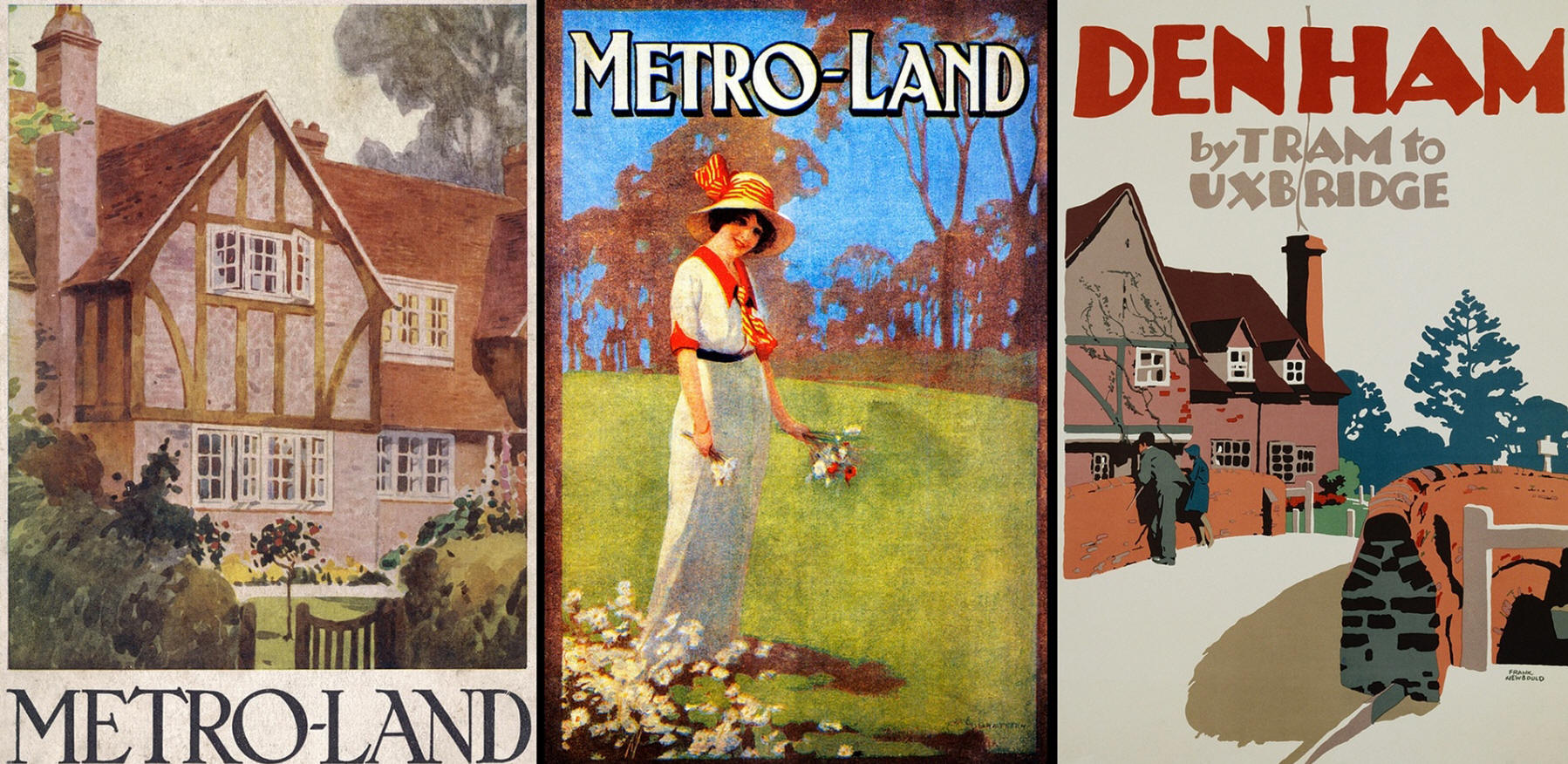

Metroland, 100

years on:

what's become of England’s original vision of suburbia?

G

Thursday 10 September 2015 10.33 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/sep/10/

metroland-100-years-england-original-vision-suburbia

The

Metropolitan Railway’s PR people

accidentally invented English suburbia.

Photograph:

Alamy/Swim Ink 2/Corbis

Metroland, 100

years on:

what's become of England’s original vision of suburbia?

G

Thursday 10 September 2015 10.33 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/sep/10/

metroland-100-years-england-original-vision-suburbia

A photo of a new housing development

in San

Jose, CA, USA.

Photo by Sean O'Flaherty

Date : ?

Source: Wikipedia - 7 October 2009

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:South_San_Jose_(crop).jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:South_San_Jose.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_the_United_States

suburb

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2023/may/12/

homes-for-sale-in-the-super-suburbs-in-pictures

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/feb/03/

enfield-experiment-london-cities-economy

https://www.economist.com/britain/2005/06/02/

wisteria-lane

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/dec/31/

britishidentity.housing

suburbia

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/sep/10/

metroland-100-years-england-original-vision-suburbia

suburb / fringe suburb / suburbia

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/12/

opinion/texas-redistricting-maps-gerrymandering.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/15/

sunday-review/future-suburb-millennials.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/

realestate/city-suburbia-exodus.html

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/mar/22/

alec-dawson-nobody-claps-anymore-perugia-social-photo-festival

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/

realestate/communities/robert-e-simon-jr-founder-of-reston-va-dies-at-101.html

http://www.npr.org/2014/03/09/

287877060/city-versus-suburb-a-longstanding-divide-in-detroit

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/06/

suburban-disequilibrium/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/

opinion/the-death-of-the-fringe-suburb.html

residential suburbs / suburban offices

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/

opinion/to-rethink-sprawl-start-with-offices.html

suburban corporate landscapes

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/

opinion/to-rethink-sprawl-start-with-offices.html

suburban landscape

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2006/jul/17/

communities.homes

exurbs

USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/11/03/

500506308/michigan-community-clashes-over-embrace-of-immigrants

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/15/

national/15exurb.html

city > suburbs > Detroit

USA

http://www.npr.org/2014/03/09/

287877060/city-versus-suburb-a-longstanding-divide-in-detroit

suburban sprawl

USA

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/28/

commutings-hidden-cost/

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/15/sunday-review/

is-suburban-sprawl-on-its-way-back.html

sprawling

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/29/us/

memphis-aims-to-be-a-friendlier-place-for-cyclists.html

commuting

USA

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/28/

commutings-hidden-cost/

planner UK

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/jul/17/

communities.homes

sprawl / urban sprawl

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/opinion/

to-rethink-sprawl-start-with-offices.html

on the outskirts of

N

deprived boroughs

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/28/

englands-poorest-spend-gambling-machines

Corpus of news articles

Arts >

Architecture, Towns, Cities >

Suburbs

Can

Paradise Be Planned?

APRIL 18,

2014

The New York Times

The Opinion Pages

Contributing Op-Ed Writer

When the

architect Robert A. M. Stern was a kid in the ‘40s, he used to spend his Sundays

perusing The New York Times real estate section. In those days, recalls the

self-described “modern traditionalist” best known for buildings like 15 Central

Park West and the George W. Bush Presidential Library, “It was all about new

houses that were being built in suburbia. I would look at them and redraw the

plans. At the basic level I thought they were so damn bad and I thought I could

do better.”

Decades later, Stern is still fed up with the state of suburbia and remains

resolutely committed to its betterment. He’s now thrown down the gauntlet with

what can be described as a McMansion-size manifesto called “Paradise Planned:

The Garden Suburb and the Modern City.”

Stern and his co-authors David Fishman and Jacob Tilove want to bring back the

garden suburb, and in so doing hope to restore a “tragically interrupted,

150-year-old tradition.” While the book engages a bit with contemporary issues

plaguing suburbia — homogeneity, automobile-dependency, sprawl — its primary

focus is former and existing garden suburbs, in hopes of transforming the ways

future suburbs are created. (It also continues a deep and fractured academic

debate among modernists, traditionalists and a whole host of other “ists,” but

we won’t bother ourselves with that here.)

“Paradise Planned” appears at a time when suburbia is rapidly losing its appeal.

As The Times reported Thursday, suburbs are experiencing a major exodus as young

people move to cities — and stay there. They’re increasingly delaying, or

avoiding altogether, the “inevitable” move to suburbia. Young people want what

cities have to offer. Can suburbia shift its own paradigm to give them something

similar? Stern would say yes — that the garden suburb can do just that.

The garden suburb is — because it still exists in many places — a planned,

self-contained village located usually outside a major city. Ideally, it

features a variety of housing types, though by variety, we’re talking

single-family homes and a few low-rise multifamily buildings. These buildings

are similar in architectural style, but similar is understating it. The

vernacular of the garden suburb is most definitely traditional — some modernist

examples crop up but they were either never built (i.e., Frank Lloyd Wright’s

Broadacre City and Norman Bel Geddes’s Futurama, both of which might have been

darn near close to paradise) or were hard to love (such as the Mussolini-backed

Sabaudia). In contrast to the suburbs we’ve come to be most familiar with, these

featured homes are situated in a comfortably dense, highly walkable environment

designed around a public center or square.

Stern sees the garden suburb as an antidote to the current suburban sprawl but

also views it as a smart way to think about what he calls in the book “the

middle city,” neighborhoods found in cities like Detroit, for example, where, he

writes, “now, virtually empty of people and buildings, [they] have no

discernible assets except the infrastructure of the streets and utility systems

buried under them.”

While the garden suburb does provide a nice alternative to bad suburban

development, the book isn’t very prescriptive about how that retrofitting might

happen (check out Galina Tachieva’s “Sprawl Repair Manual” for a more

comprehensive strategy).Stern proposes what is probably a smarter use of the

garden suburb today: deploying it in a very suburbanized, spread-out city — say,

Indianapolis or San Jose — that would work better as a collection of

neighborhoods than as a sprawling metropolis. “I think there is a

misunderstanding of what a city is,” Stern told me recently. “A city has

suburban areas inside it. Even the city of New York, once you get off the

island, is suburban in scale.” Some good local examples would include Prospect

Park South in Brooklyn and Sunnyside in Queens.

What people are trying to do, Stern told me, is to get out of what he calls

“sprawling ‘slurbias’ where they’re chained to their cars whether they’re taking

their kids to school or getting a haircut. Everyone doesn’t want to live in a

90th floor penthouse overlooking the Hudson River but people do want to live in

nice communities.”

But what about the people who live in the very antithesis of what’s he’s arguing

for, yet the form that is most prevalent on the American landscape. Let’s call

it the “post-garden suburb.” Well, Stern says that in order to go forward, we

often have to go backward. It’s hard to dispute that these well-planned

communities he has documented are often the perfect mix between town and country

— lots of green space, community gathering spots, paths for ambling, all in

dense (but not too dense) urban settings. But it is easier to suggest that

publishing a 1,072-page, 12-1/2-pound hardcover book might not be the best

strategy for pushing the needle. When all is said and done, it’s a solid

historical document but only offers models for what to do if you have the luxury

of starting from square one. As Stern well knows, those opportunities are few

and far between. “You have to put the infrastructure in before you build the

community,” he says. “And governments won’t even do that anymore. It’s come to

that. Arguments are about who can put in the least amount of infrastructure into

these developments.”

Case in point, one of the more successful (or controversial, depending on your

point of view) garden suburbs of recent times — Celebration, Fla. — which, Stern

admits, needed Disney’s backing to become a reality. I’m not sure that

corporation-financed communities offer a replicable — or desirable — model,

however, particularly when they are described, as Celebration was by Andrew

Ross, an academic (and my former Ph.D. adviser) who spent a year living there,

as “the product of a company that merchandises the semi-real with an attitude

that the architectural historian Vincent Scully once described as ‘unacceptably

optimistic.'”

And while it’s lovely to look at the suburbs of yore in this tome, perhaps

that’s the real problem with “Paradise Planned”: it’s unacceptably optimistic.

Stern shows what was as a means of demonstrating what could be. In contrast, the

photographer Christoph Gielen shows, with his startling aerial photographs of

contemporary suburbs, what actually is. The only rational response to these

images would seem to be, “What the hell were we thinking?”

“It is an encounter in the most literal sense,” writes the futurist Geoff

Manaugh in Gielen’s jarring yet utterly mesmerizing new book, “Ciphers.” “A

forensic confrontation with something all but impossible to comprehend.”

We may be starting to comprehend the mess a little better. Smart Growth

America’s just-released report, “Measuring Sprawl 2014,” is illuminating. In it,

researchers determine that several quality-of-life factors improve as sprawl

decreases. Individuals living in compact, connected metro areas (akin to the

garden suburb) were found to have greater economic mobility. These folks spend

less on both housing and transportation, and have greater transit options. They

tend to live longer, safer, healthier lives than their peers in metro areas with

sprawl. The report cites evidence that people who live in areas with sprawl

suffer from more obesity, high blood pressure and fatal car crashes.

Whether viewed through the lens of data, nostalgia or aerial photography,

automobile-dependent sprawl not only has a damaging impact on the environment

but is also connected to poorer economy, health and safety. There’s no question

that things need to change. The Smart Growth report suggests that many

decision-makers like mayors and planning commissioners are re-examining

traditional zoning, economic development incentives, transportation access and

availability (or the lack thereof), and other policies that have helped to

create sprawling development patterns — and are opting instead to create more

connections, transportation choices and walkable neighborhoods in their

communities. Still, I fear we’re going to be stuck in traffic for a long time.

Can Paradise Be Planned?, NYT, 18.4.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/19/opinion/can-paradise-be-planned.html

To Rethink Sprawl, Start With Offices

November 25, 2011

The New York Times

By LOUISE A. MOZINGO

San Francisco

IN an era of concern about climate change, residential suburbs are the focus of

a new round of critiques, as low-density developments use more energy, water and

other resources. But so far there’s been little discussion of that other

archetype of sprawl, the suburban office.

Rethinking sprawl might begin much more effectively with these business

enclaves. They cover vast areas and are occupied by a few powerful entities,

corporations, which at some point will begin spending their ample reserves to

upgrade, expand or replace their facilities.

The bucolic business office is not a state-of-the-art workplace but rather a

decades-old model of corporate retreat. In 1942 the AT&T Bell Telephone

Laboratories moved from its offices in Lower Manhattan to a new, custom-designed

facility on 213 acres outside Summit, N.J.

The location provided space for laboratories and quiet for acoustical research,

and new features: parking lots that allowed scientists and engineers to drive

from their nearby suburban homes, a spacious cafeteria and lounge and, most

surprisingly, views from every window of a carefully tended pastoral landscape

designed by the Olmsted brothers, sons of the designer of Central Park.

Corporate management never saw the city center in the same way again. Bell Labs

initiated a tide of migration of white-collar workers, especially as state and

federal governments conveniently extended highways into the rural edge.

In metropolitan areas across America, corporate campuses for research and

development units proliferated and top executives ensconced themselves in

palatial estates like the Deere & Co. Administrative Center outside Moline, Ill.

Meanwhile, branch offices, small corporations and start-ups found footing in the

office parks that lined suburban highways and arterial roads, like those of

Silicon Valley in California and the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina.

Born in an era of seemingly limitless resources, this pastoral capitalism

restructured the landscape of metropolitan regions; today it accounts for well

over half the office space in the United States.

Yet suburban offices are even more unsustainably designed than residential

suburbs. Sidewalks extend only between office buildings and parking lots,

expanses of open space remain private and the spreading of offices over large

zones precludes effective mass transit.

These workplaces embody a new form of segregation, where civic space connecting

work to the shops, housing, recreation and transportation that cities used to

provide is entirely absent. Corporations have cut themselves off from

participation in a larger public realm.

Rethinking pastoral capitalism is integral to creating a connected, compact

metropolitan landscape that tackles rather than sidesteps a post-peak-oil

future. This requires three interrelated strategies. State and federal

governments should stop paying for new highway extensions that essentially

subsidize the conversion of agricultural land for development, including

corporate offices. Existing infrastructure needs maintenance and renewal, not

expansion.

Suburban jurisdictions that now require little of the next corporate campus

other than plentiful parking can demand more. For instance, they can use zoning

codes to require pedestrian, bicycle and mass-transit links to adjacent

residential developments. Add to the mix new public spaces, a greater diversity

of uses, and transit between multiple employment centers and residential

districts — not only to and from the downtown — and suburban corporate offices

could initiate a wave of reform.

While suburban offices will continue to exist, some corporations can re-occupy

city centers that they abandoned two generations ago. Development parcels,

vacant offices and economic subsidies lie waiting in cities like Cleveland,

Hartford, Raleigh, N.C., and Birmingham, Ala. These downtowns are well served by

transit and pedestrian connections, a mix of retail and service uses, and a

surprising amount of newly built and renovated housing where workers can live.

All three steps — a halt to agricultural land conversion, connecting dispersed

employment centers with alternative transit, and encouraging downtown

development — are needed to create renewed, civic-minded corporate workplaces

and, in the process, move toward sustainable cities. Even leaving aside climate

change, very soon the price of energy will make the dispersed, unconnected,

low-density city-building pattern impossibly costly. Those jurisdictions and

businesses that first create livable, workable, post-peak-oil metropolitan

regions are the ones that will win the future.

Louise A. Mozingo,

a professor of landscape architecture

and environmental

planning

at the University of California, Berkeley,

is the author of “Pastoral

Capitalism:

A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes.”

To Rethink Sprawl, Start With Offices, NYT,

25.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/opinion/

to-rethink-sprawl-start-with-offices.html

The Death of the Fringe Suburb

November 25, 2011

The New York Times

By CHRISTOPHER B. LEINBERGER

Washington

DRIVE through any number of outer-ring suburbs in America, and you’ll see

boarded-up and vacant strip malls, surrounded by vast seas of empty parking

spaces. These forlorn monuments to the real estate crash are not going to come

back to life, even when the economy recovers. And that’s because the demand for

the housing that once supported commercial activity in many exurbs isn’t coming

back, either.

By now, nearly five years after the housing crash, most Americans understand

that a mortgage meltdown was the catalyst for the Great Recession, facilitated

by underregulation of finance and reckless risk-taking. Less understood is the

divergence between center cities and inner-ring suburbs on one hand, and the

suburban fringe on the other.

It was predominantly the collapse of the car-dependent suburban fringe that

caused the mortgage collapse.

In the late 1990s, high-end outer suburbs contained most of the expensive

housing in the United States, as measured by price per square foot, according to

data I analyzed from the Zillow real estate database. Today, the most expensive

housing is in the high-density, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods of the center

city and inner suburbs. Some of the most expensive neighborhoods in their

metropolitan areas are Capitol Hill in Seattle; Virginia Highland in Atlanta;

German Village in Columbus, Ohio, and Logan Circle in Washington. Considered

slums as recently as 30 years ago, they have been transformed by gentrification.

Simply put, there has been a profound structural shift — a reversal of what took

place in the 1950s, when drivable suburbs boomed and flourished as center cities

emptied and withered.

The shift is durable and lasting because of a major demographic event: the

convergence of the two largest generations in American history, the baby boomers

(born between 1946 and 1964) and the millennials (born between 1979 and 1996),

which today represent half of the total population.

Many boomers are now empty nesters and approaching retirement. Generally this

means that they will downsize their housing in the near future. Boomers want to

live in a walkable urban downtown, a suburban town center or a small town,

according to a recent survey by the National Association of Realtors.

The millennials are just now beginning to emerge from the nest — at least those

who can afford to live on their own. This coming-of-age cohort also favors urban

downtowns and suburban town centers — for lifestyle reasons and the convenience

of not having to own cars.

Over all, only 12 percent of future homebuyers want the drivable suburban-fringe

houses that are in such oversupply, according to the Realtors survey. This lack

of demand all but guarantees continued price declines. Boomers selling their

fringe housing will only add to the glut. Nothing the federal government can do

will reverse this.

Many drivable-fringe house prices are now below replacement value, meaning the

land under the house has no value and the sticks and bricks are worth less than

they would cost to replace. This means there is no financial incentive to

maintain the house; the next dollar invested will not be recouped upon resale.

Many of these houses will be converted to rentals, which are rarely as well

maintained as owner-occupied housing. Add the fact that the houses were built

with cheap materials and methods to begin with, and you see why many fringe

suburbs are turning into slums, with abandoned housing and rising crime.

The good news is that there is great pent-up demand for walkable, centrally

located neighborhoods in cities like Portland, Denver, Philadelphia and

Chattanooga, Tenn. The transformation of suburbia can be seen in places like

Arlington County, Va., Bellevue, Wash., and Pasadena, Calif., where strip malls

have been bulldozed and replaced by higher-density mixed-use developments with

good transit connections.

Reinvesting in America’s built environment — which makes up a third of the

country’s assets — and reviving the construction trades are vital for lifting

our economic growth rate. (Disclosure: I am the president of Locus, a coalition

of real estate developers and investors and a project of Smart Growth America,

which supports walkable neighborhoods and transit-oriented development.)

Some critics will say that investment in the built environment risks repeating

the mistake that caused the recession in the first place. That reasoning is as

faulty as saying that technology should have been neglected after the dot-com

bust, which precipitated the 2001 recession.

The cities and inner-ring suburbs that will be the foundation of the recovery

require significant investment at a time of government retrenchment. Bus and

light-rail systems, bike lanes and pedestrian improvements — what traffic

engineers dismissively call “alternative transportation” — are vital. So is the

repair of infrastructure like roads and bridges. Places as diverse as Los

Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Dallas, Charlotte, Denver and Washington have

recently voted to pay for “alternative transportation,” mindful of the dividends

to be reaped. As Congress works to reauthorize highway and transit legislation,

it must give metropolitan areas greater flexibility for financing

transportation, rather than mandating that the vast bulk of the money can be

used only for roads.

For too long, we over-invested in the wrong places. Those retail centers and

subdivisions will never be worth what they cost to build. We have to stop

throwing good money after bad. It is time to instead build what the market

wants: mixed-income, walkable cities and suburbs that will support the knowledge

economy, promote environmental sustainability and create jobs.

Christopher B. Leinberger

is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution

and professor of practice in urban and regional planning

at the University of

Michigan.

The Death of the Fringe Suburb, NYT,

25.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/opinion/

the-death-of-the-fringe-suburb.html

Gas prices drive push

to reinvent America's suburbs

29 July 2008

USA Today

By Haya El Nasser

MARICOPA, Ariz. — Mayor Tony Smith proudly waves a thank-you letter from a

major builder telling him that no city has ever reached out to him in his

30-year career the way Maricopa did.

What Maricopa has been doing is unusual, especially for a distant suburb.

This city about 35 miles south of Phoenix is asking builders not to develop just

isolated subdivisions behind walls, but whole communities that encourage walking

by including stores, schools and services nearby.

"The people of Maricopa don't want to be a bedroom community, a city of

rooftops," Smith says. "They want a self-sustained community."

Especially today. As gas prices hover around $4 a gallon, the nation's

far-flung suburbs — which have boomed because they could provide larger homes at

cheaper prices to those willing to drive farther — are losing their appeal.

Soaring energy costs and the foreclosure epidemic have jolted many Americans

into realizing that their lifestyles are at risk. For many, ever-lengthening

commutes in the search for affordable homes no longer make financial sense.

In Maricopa and elsewhere, a movement is underway to transform suburbs from

bedroom communities that sprang up during an era of cheap gasoline to lively,

more cosmopolitan places that mix houses with jobs, shops, restaurants, colleges

and entertainment.

Suburbs on the far edge of metro areas are turning aside strip malls and

creating new downtowns and neighborhoods that favor pedestrians. They're trying

to attract more employers and services such as hospitals, colleges and small

airports.

The appeal of urbanism is spreading to far suburbs such as Rancho Cucamonga,

Calif.(about 42 miles east of Los Angeles), and Huntersville, N.C., about 16

miles north of Charlotte. Centers that combine residential, retail, office and

entertainment are becoming popular far from urban centers.

Small historic towns on the edge of metropolitan areas such as Brighton, Colo.,

northeast of Denver, and Plainfield, Ill., southwest of Chicago, are emphasizing

their Main Streets and history to provide a sense of community outside the walls

of sprawling subdivisions.

Mass transit is being embraced by towns that wouldn't have been born without the

automobile. Here in Maricopa, the city introduced bus service to Phoenix and

Tempe this year, providing the first mass transit alternative to residents, many

of whom commute about 35 miles to Phoenix.

Such changes could have a profound effect on the way the nation develops as it

prepares to absorb an estimated 100 million more people by about 2040.

The scent of change is in the air in Maricopa, even in the way city officials

talk. Words such as "bedroom community" have become dirty words. "Green,"

"sustainable," "walkable," "mass transit," "conservation," "open space" and

"energy-efficient" punctuate the suburban dialogue.

"Absolutely, suburbs are not going to go away," says David Goldberg, spokesman

for Smart Growth America, a national coalition of groups pushing for

conservation and sustainable growth. "But the math is becoming very clear."

Until now, people were willing to drive increasingly far for a home they could

afford. "Drive-till-you-qualify collapsed," Goldberg says. "It's done. It's not

going to work as a housing strategy anymore."

Living costs soar

In the past year, as gas prices skyrocketed, the housing bubble burst and

transit ridership soared, the cost of living farther out for many Americans went

from manageable to pricey.

An analysis of real estate data by Fiserv Lending Solutions shows that home

prices have fallen more in towns and neighborhoods far from urban centers than

in close-in suburbs.

Developers traditionally have flocked to fields at the edge of metro areas to

avoid the stricter zoning rules and higher fees they face in older, more densely

populated communities. But that could be changing.

"The trends that pushed housing demand toward distant suburbs and rural areas

were not sustainable," says David Stiff, chief economist at Fiserv. "The problem

is that it can be two, three, four times as expensive to develop in close-in

neighborhoods vs. outlying neighborhoods, if there's any space at all."

If gas prices continue to climb or government provides incentives to build more

densely and closer in, development patterns should evolve, planners say.

"People respond to economic incentives," Stiff says. "Reducing commuting costs,

trying to be more environmentally conscious and trying to find the cheapest

housing affect decisions simultaneously."

"We're sort of stuck with retrofitting the suburbs," says Scott Bernstein, head

of the Center for Neighborhood Technology, which for years has urged that

transportation costs be a criterion for mortgage qualification. "That's not all

that bad. … There's nothing like a crisis to get people to try something."

Fresh ideas about development are spreading. A new website gives "walk" scores

for more than 2,500 neighborhoods in the 40 largest cities (walkscore.com).

Bernstein's group publishes a housing and transportation affordability index for

52 metropolitan areas (htaindex.cnt.org/).

Kenneth Himmel says now is "the perfect moment to be doing everything we're

talking about."

The developer of the Reston Town Center in Virginia, the Time Warner Center in

New York and City Place in West Palm Beach, Fla., says: "Some people will say,

'For $300,000 to $325,000, what are my options to live closer?' Maybe it's a

smaller home. … Do they want to drive or do they want to be five or 10 minutes

from their office? People will make the trade."

The new reality

The Phoenix area is legendary for sprawl. The city alone covers 517 square

miles. Surrounding it is 14,000 square miles (twice the size of New Jersey) of

desert dotted by seas of rooftops.

Foreclosures have hit the region hard — more than 5,500 the first six months of

this year. Home construction permits have slowed by more than half in many

communities. Still, building crews are grading tracts of land far from downtown.

Buckeye, more than 30 miles west of Phoenix, and Maricopa, a similar distance to

the south, are the suburbs that have the highest number of new single-family

home permits.

It's there that the seeds of change are taking root.

"We've got to get jobs to keep people from driving," says Buckeye Mayor Jackie

Meck, who worries that gas "could easily go to $8, $10" a gallon.

Meck and town manager Jeanine Guy say Buckeye's goal was never to be a bedroom

community but a gateway to California and the Pacific Rim. Already, developers

of a master-planned community on 1,100 acres 30 miles beyond Buckeye — 60 miles

from Phoenix — are rethinking their project because of fuel costs. They want to

turn it into a distribution center that would cut gas costs for truckers from

the West who are delivering goods to the Phoenix area.

In Maricopa, the city for the first time is encouraging builders to create

sustainable communities that use alternative forms of energy or are near jobs,

goods and services. Already, the city is home to Arizona's first ethanol plant

and a facility that uses recycled water to flush toilets. And there are the

commuter buses to downtown Phoenix and Tempe.

When gas prices inched toward $4 a gallon, Donna Nance bemoaned her 40-mile,

one-way commute to work her job as the court clerk in downtown Phoenix. Gas

would now cost her $60 a week, a blow for a single mom who had moved here to get

a house at a better price.

She considered moving closer, at the risk of giving up her three-bedroom,

single-family home and might have done it if Maricopa had not introduced

Phoenix-bound commuter buses in April. Nance, 43, now drives 7 miles to the bus

stop and enjoys the ride. Even if gas prices keep climbing, Nance says she has

no reason to leave.

"We hit a sweet spot starting a transit program here," Mayor Smith says.

It's a reflection of how some suburbs are trying to replace their "middle of

nowhere" image with a "there." "Maybe gas drops to $3 a gallon and people will

say we don't need to do this anymore," says Guy, the Buckeye town manager. "We

do."

Gas prices drive push to

reinvent America's suburbs,

UT, 29.7.2008,

https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2008-07-29-

nosale_N.htm

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia > Arts

architecture, towns, cities

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

transports

Related > Anglonautes >

Arts

architects, architecture

Related

Guardian > Life in the suburbs: share your pictures

2014

https://witness.theguardian.com/assignment/

5386098ce4b0f6774a4ff2cb?INTCMP=mic_231930

|