|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Architecture > 20th century

> Modernism

A 22-acre estate, Sea Cove Farms,

with 2,000 feet of waterfront

on Seatuck and Little Seatuck

Creeks in Eastport,

is about to enter the market at $12 million.

The bi-level home,

designed by the modernist architect

Horace

Gifford,

was completed in 1979.

An extension to its western side, seen above,

was designed by

Philip Babb in 1994-96.

The 6,000-square-foot cedar-clad house,

set on a landscaped

5.1 acre parcel,

has six bedrooms and six bathrooms.

The property includes a 2.1 acre buffer lot to the east

and a

14.8 acre lot used for organic farming.

Photograph: Nicole Bengiveno

The New York Times

Real Estate

A Secluded Modern

22-Acre Eastport Estate at $12 Million

NYT JULY 25, 2014

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/

realestate/22-acre-eastport-estate-at-12-million.html

The master suite has 11-foot ceilings, a fireplace,

and an adjacent home office with curved walls of glass

overlooking Seatuck Creek and Little Seatuck Creek.

Photograph: Nicole Bengiveno

The New York Times

Real Estate

A Secluded Modern

22-Acre Eastport Estate at $12 Million

NYT JULY 25, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/realestate/22-acre-eastport-estate-at-12-million.html

The living room section of the great room

has a wood-burning

fireplace with a stone surround;

a floating staircase leads to the great room,

which has views

across Moriches Bay to Dune Road

in Westhampton.

Photograph: Nicole Bengiveno

The New York Times

Real Estate

A Secluded Modern

22-Acre Eastport Estate at $12 Million

NYT JULY 25, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/realestate/22-acre-eastport-estate-at-12-million.html

The 20-by-40 foot great room

has cedar walls, oak floors,

ten-foot ceilings

and a wall of south-facing windows

with sliders that open to

the half-moon shaped deck.

Photograph: Nicole Bengiveno

The New York Times

Real Estate

A Secluded Modern

22-Acre Eastport Estate at $12 Million

NYT JULY 25, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/realestate/22-acre-eastport-estate-at-12-million.html

modernist UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/gallery/2025/feb/28/

brutalist-modernist-homes-for-sale-england-barbican

USA > modernism

UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2018/sep/11/

memorable-monuments-to-american-modernism-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2018/jun/05/

suburban-modernism-metroland-london-architecture

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/06/

531751099/william-krisel-architect-who-helped-define-california-modernism-dies-at-92

http://www.npr.org/2016/02/21/

467352937/meet-the-architect-who-helped-bring-modernism-to-the-masses

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/26/us/

palm-springs-modern-architecture-tours.html

Modernist design after World War II

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/17/

arts/design/walter-pierce-architect-of-modernist-homes-is-dead-at-93.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/27/

arts/design/balthazar-korab-architectural-photographer-dies-at-86.html

Modernist architect

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/27/

arts/design/john-m-johansen-last-of-harvard-five-architects-dies-at-96.html

modernist

architecture UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/jul/19/

modernist-architecture-photography-corbusier-concrete-gibberd-hill

modernist villa UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/jun/30/

eileen-gray-e1027-corbusier-review

modernist house

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/

realestate/22-acre-eastport-estate-at-12-million.html

the Modern

House UK

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/gallery/2015/sep/12/

the-modern-house-in-pictures

the Harvard Five

USA

a group that made New Canaan, Conn.,

a hotbed of architectural experimentation

in the 1950s and ’60s

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/27/

arts/design/john-m-johansen-last-of-harvard-five-architects-dies-at-96.html

Interior with Mirrored

Wall, 1991. Roy

Lichtenstein

Oil and Magna on canvas,, 126 1/8 x 160 inches.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

92.4023.

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein.

http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_work_lg_88_3.html

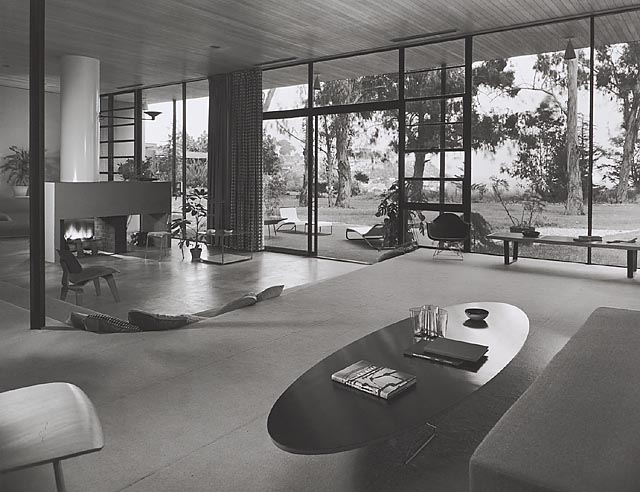

Julius Shulman

Case Study House #22 1960

Los Angeles, CA

Pierre Koenig, architect

gelatin silver print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/js13.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_2.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/obituaries/story/0,3604,1190539,00.html

http://www.usc.edu/dept/architecture/slide/koenig/

Related

http://www.latimes.com/features/home/la-hm-stahl27-2009jun27,0,504751.story

Julius Shulman

Case Study House #21 1958

Los Angeles, CA

Pierre Koenig, architect

chromogenic print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_2.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

Julius Shulman

Singleton House 1960

Los Angeles, CA

Richard Neutra, architect

gelatin silver print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_2.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

Julius Shulman

Chuey House 1958

Los Angeles, CA

Richard Neutra, architect

gelatin silver print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_2.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

Julius Shulman Recreation

Pavilion, Mirman Residence 1959

Arcadia, CA

Buff, Straub and Hensman, architects

chromogenic print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_2.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

Julius Shulman

Case Study House #9 / Entenza House 1950

Pacific Palisades, CA

Eames & Saarinen, architects

gelatin silver print

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/exhibitions/2003/2003_06/shulman/shulman_2003_1.html

http://www.wirtzgallery.com/main.html

Architecture

Architect Without Limits

May 15, 2009

The New York Times

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

Frank Lloyd Wright died half a century ago, but people are

still fighting over him.

The extraordinary scope of his genius, which touched on every aspect of American

life, makes him one of the most daunting figures of the 20th century. But to

many he is still the vain, megalomaniacal architect, someone who trampled over

his clients’ wishes, drained their bank accounts and left them with leaky roofs.

So “Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward,” which opens on Friday at the

Guggenheim Museum, will be a disappointment to some. The show offers no new

insight into his life’s work. Nor is there any real sense of what makes him so

controversial. It’s a chaste show, as if the Guggenheim, which is celebrating

its 50th anniversary, was determined to make Wright fit for civilized company.

The advantage of this low-key approach is that it puts the emphasis back where

it belongs: on the work. There are more than 200 drawings, many never exhibited

publicly before. More than a dozen scale models, some commissioned for the show,

give a strong sense of the lucidity of his designs and the intimate relationship

between building and landscape that was such a central theme of his art.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition conveys not only the remarkable scope of his

interests, which ranged from affordable housing to reimagining the American

city, but also the astonishing cohesiveness of that vision

— an achievement that has been matched by only one or two other architects in

the 20th century.

One way to experience the show is as a straightforward tour of Wright’s

masterpieces. Organized by Thomas Krens and David van der Leer, it is arranged

in roughly chronological order, so that you can spiral up through the highlights

of his career: the reinvention of the suburban home and the office block, the

obsession with car culture, the increasingly outlandish urban projects.

There is a stunning plaster model of the vaultlike interior of Unity Temple,

built in Oak Park between 1905 and 1908. Just a bit farther up the ramp, another

model painstakingly recreates the Great Workroom of the Johnson Wax Headquarters

in Racine, Wis., with its delicate grid of mushroom columns and milky glass

ceiling.

Such tightly composed, inward-looking structures contrast with the free-flowing

spaces that we tend to associate with Wright’s fantasy of a democratic, agrarian

society.

But as always with Wright, the complexity of his approach reveals itself only

after you begin to fit the pieces together. For Wright, the singular masterpiece

was never enough. His aim was to create a framework for an entire new way of

life, one that completely redefined the relationships between individual, family

and community. And he pursued it with missionary zeal.

Wright went to extreme lengths to sell his dream of affordable housing for the

masses, tirelessly promoting it in magazines.

The second-floor annex shows a small sampling of its various incarnations,

including an elaborate model of the Jacobs House (1936-37), its walls and floors

pulled apart and suspended from the ceiling on a system of wires and lead

weights. One of Wright’s earliest Usonian houses, the one-story Jacobs structure

in Madison, Wis., was made of modest wood and brick and organized around a

central hearth. Its L-shape layout framed a rectangular lawn, locking it into

the landscape, so that the homeowner remained in close touch with the earth.

The ideas Wright explored in such projects were eventually woven into grander

urban fantasies, first proposed in Broadacre City and later in The Living City

project. In both, Usonian communities were dispersed over an endless matrix of

highways and farmland, punctuated by the occasional residential tower.

The subtext of these plans, of course, was Wright’s war with the city. To

Wright, the congested neighborhoods of the traditional city were anathema to the

spirit of unbridled individual freedom. His alternative, shaped by the car,

represented a landscape of endless horizons. Sadly, it was also a model for

suburban sprawl.

Wright continued to explore these themes until the end of his life, even as his

formal language evolved. A model of the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and

Planetarium captures his growing obsession with the ziggurat and the spiral. A

tourist destination that was planned for Sugarloaf Mountain, Md., but never

built, the massive concrete structure coiled around a vast planetarium. The

project combines his love of cars and his fascination with primitive forms, as

if he were striving to weave together the whole continuum of human history.

In his 1957 Plan for Greater Baghdad, Wright went a step further, adapting his

ideas to the heart of the ancient city. The plan is centered on a spectacular

opera house enclosed beneath a spiraling dome and crowned by a statue of

Alladin. Set on an island in the Tigris, the opera house was to be surrounded by

tiers of parking and public gardens. A network of roadways extends like tendrils

from this base, weaving along the edge of the river and tying the complex to the

old city.

Just across the river, another ring of parking, almost a mile in diameter,

encloses a new campus for Baghdad University.

Wright’s fanciful design was never built, but it demonstrates the degree to

which he remained distrustful of urban centers. Stubborn to the end, he saw the

car as the city’s salvation rather than its ruin. The cosmopolitan ideal is

supplanted by a sprawling suburbia shaded by palms and date trees.

And what of the Guggenheim? Some will continue to see it as an example of

Wright’s brazen indifference to the city’s history. With its aloof attitude

toward the Manhattan street grid, the building still pushes buttons.

For his part, Wright saw the spiral as a symbol of life and rebirth. The

reflecting pool at the bottom of his rotunda represented a seed, part of his

vision of an organic architecture that sprouts directly from the earth.

Yet Wright also needed the city to make his vision work. The force of the

spiral’s upward thrust gains immeasurably from the grid that presses in on all

sides. The ramps, too, can be read as an extension of the street life outside.

Coiled tightly around the audience, they replicate the atmosphere of urban

intensity that Wright supposedly so abhorred.

Or maybe not. In preparing for the show, the Guggenheim’s curators decided to

remove the frosting from a window at the lobby’s southwest corner. The window

frames a vista over a low retaining wall toward the corner of 88th Street and

Fifth Avenue, where you can see people milling around the exterior of the

building. It is the only real view out of the lobby, and it visually locks the

building into the streetscape, making the city part of the composition.

I choose to see it as a gesture of love, of a sort, between Wright and the city

he claimed to hate.

Architect Without

Limits,

NYT,

15.5.2009,

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/15/

arts/design/15wrig.html

Wright

- Designed Fountain Works _ Finally

October 26, 2007

Filed at 10:48 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

LAKELAND, Fla. (AP) -- The giant water fountain Frank Lloyd Wright designed

here is no longer the unworkable dud it was for decades.

Thanks to computers and extensive restoration, the ''Water Dome'' finally

produces the three-story dome of water Wright envisioned 70 years ago as the

centerpiece of his architectural design for Florida Southern College's campus.

''He was very far ahead of his time, and sometimes materials are just catching

up with him,'' said New York-based architect Jeff Baker, who heads preservation

work at the college where 12 structures make up the largest collection of

Wright's works on a single site.

More than 1,000 people cheered the fountain's opening Thursday, when the school

celebrated Wright's vision if not his engineering ability. Spectators ringed the

fountain more than 10 deep in places, and some had black and white pictures

taken with a cutout of Wright.

Construction of the fountain took place between 1941 and 1958, and Wright

himself visited the campus during construction. Florida Southern students today

attend class in Wright-designed rooms and walk under his covered esplanades. The

school, affiliated with the United Methodist Church, also holds services in the

architect's chapels.

Until now, his Water Dome though was a disappointment. Its pool was completed in

1948, and contemporary newspapers said the fountain's opening was imminent. That

never happened. Low water pressure, or low funds, may have been the cause. In

the late 1960s, the school covered much of the pool with cement, creating three

smaller ponds.

A $1 million restoration started a year ago. Preservationists visited Wright's

archives in Spring Green, Wis., to research early plans and letters between

engineers. Paint analysis recreated the original bright aqua of the fountain's

basin, and a Wright-designed pump house was reclaimed.

Other features, however, Wright might not recognize: Computers control the water

streaming from the 74 nozzles; public water rather than a well fills the basin,

which is a few inches shallower because of new building codes. Architects also

added underwater lighting.

There's even a modern solution for a problem rumored in Wright's time: that wind

blew the water around, drenching students. A wind meter on top of a nearby

building can now help adjust the water height if winds get too high.

That feature had been turned off Thursday night, however, so the dome would stay

at its maximum, 45-foot height. And mist swept off the fountain, cutting short a

performance by a band under its path. Most students didn't seem to mind,

however, taking pictures with cameras before heading to the library or dorms.

Freshman Shannon Ryan, 18, rode a Ferris wheel the school had set up for an

overhead view. How would Wright feel about finally seeing his fountain on? Ryan

thought she knew: ''Um, hello, it took you long enough.''

Wright - Designed

Fountain Works _ Finally,

NYT,

26.10.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/

AP-Wright-Fountain.html - broken link

Group Seeks

to Restore 1916 Wright Home

June 16, 2007

Filed at 10:25 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

MILWAUKEE (AP) -- Pieces of architectural history sit on Milwaukee's south

side -- a row of four duplexes and two cottages designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

more than 90 years ago for low-to-moderate-income families.

But years of extreme makeovers, including aluminum siding added to one house,

rendered some of them shells of their former designs. Now a nonprofit group

wants to restore the Frank Lloyd Wright charm to one of the single-family homes

-- right down to the crushed quartz stone-infused stucco on the exterior.

Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin has bought one of the single-family houses and a

duplex, and plans to start restoring an 850-square-foot, two-bedroom home to its

1916 condition, possibly as early as fall.

The group hopes to make it a museum, inspire others to renovate the four

remaining structures and motivate architects to design housing for the

disadvantaged.

Wright historian Jack Holzhueter said the houses, known as the American

System-Built Homes, are the best example of the beloved architect's lifelong

pursuit of providing affordable housing for low-income residents.

''It's early relatively in his career, 1916,'' he said. ''It's a very large

group of buildings. No other cluster of Wright buildings begins to resemble this

one, in proximity, density, etceteras.''

Wright, who was born in Richland Center, Wis., and died in 1959 at the age of 92

in Arizona, is known for his sprawling, earth-hugging homes in the countryside,

but he took a special interest in creating low-cost shelter in urban settings.

He believed all economic classes were entitled to good architecture.

Wright produced more than 900 drawings of various designs. To reduce costs,

factory-cut materials were assembled onsite, said Mike Lilek, the group's

treasurer.

Developer Arthur Richards built the compact, geometric homes -- five of the six

have flat roofs -- in 1915 and 1916. They sold originally for $3,500 to $4,500.

Eight others have been identified around the Midwest. Wright and Richards

recruited builders from around the Midwest for the American System project

through 1917, but the effort was largely abandoned because of World War I and

Wright's other endeavors, Lilek said.

Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin bought the single-family home in 2004 for $130,000

from an owner who lived there for about 40 years and a duplex for $142,000 in

2005.

The group hopes its efforts serve as a catalyst for the entire block's

restoration, said Denise Hice, the group's president. Members also want to

create educational programs.

''We feel that it's important that we restore them as well and open them again

leading into the educational component to maybe have people design homes today

just like Wright did almost 100 years ago,'' Hice said.

Lilek expects work on the house to take more than a year.

They have so far raised $298,500 toward the $379,369 needed, Lilek said.

The home is in relatively good shape. One of the first tasks will be to remove

an unoriginal enclosed porch, which surrounds full-length windows inside. The

group wants to replace the 3/4-inch layer of stucco outside with an original

1/4-layer with crushed quartz stone. It will recondition the roof with modern

materials and rebuild an enclosed rear stairwell.

Other repairs include updating electrical, removing varnish on woodwork,

stripping the hardwood floors and restoring the wooden kitchen counter.

The Historic Preservation Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee,

School of Architecture and Urban Planning, helped research the house's original

condition, Lilek said. Its work, along with that of Italian conservator Nikolas

Vakalis, can be seen in swatches of color on the walls that show the original

paint.

Vakalis had 17 samples of finishes, plaster, stucco and paint analyzed by a lab

to determine the composition so they could be replicated. They will try to

restore as much as they can, but not if it won't hold up, Lilek said.

Eventually, they will also have furniture made, based on Wright's drawings.

Wright saved space by adding a folding door to the kitchen, a built-in kitchen

table and chairs and built-in closets, which are all still there.

Caretaker William Krueger said despite the square footage, the house is

spacious. He earned his master's degree in architecture last year and gets a

small stipend to live in the house and give tours.

''I have no problems entertaining up to 30 guests in this house,'' he said.

''It's so small and yet things are interlocked or overlapping each other.''

Hice said they have charged $2 for tours once a month for about a year and plan

to give tours during restoration.

The group eventually wants to refurbish the exterior of the duplex, which is now

a rental property. But what will be done, if anything, to the remodeled interior

has not been decided, Lilek said.

Their intent isn't to make each house into a museum. ''We're going to try and

turn these back to owner-occupied buildings,'' he said. ''I don't know if me or

you would move into a building in its 1916 condition.''

Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin bought the two houses because no one else was

making a major effort to preserve them, Hice said, except for the Arena family.

Jillayne and Dave Arena bought one of the duplexes 25 years ago. They put

hundreds of thousands of dollars into making it a one-family home, after it had

been a rental property, Jillayne Arena said.

They removed paneling, restored the original hardwood floors, added stucco on

the exterior, created 80 leaded glass windows and attached trellises to the

front.

She said living in Wright's design has taught her to approach problems

differently.

''I think when you live in a house like this you ... understand that the

conventional view, the conventional wisdom is not always what should be,'' she

said. ''So you kind of end up thinking and being perhaps a bit eccentric.''

Holzhueter, the historian, said Wright wanted to bring beauty into everyone's

home.

''Beauty was the goal -- to live in harmony with your surroundings, to have a

more beautifully proportioned and designed house for very little money,'' he

said, ''and that would bring you into a state of greater appreciation for the

world around you and for your own potential.''

Group Seeks to Restore

1916 Wright Home,

NYT,

16.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/arts/

AP-Wright-Restoration.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia >

Arts

architecture, towns, cities

Related > Anglonautes

arts > architects, architecture

|