|

learning > grammaire anglaise - niveau avancé

séquences

nominales

syntaxe, sens et valeurs énonciatives

N

+ 's +

N

=

Ngénitif

N

+ 's +

N

+ of +

N

reprise

d'un élément bien connu, repéré,

identifié

répétitif, rituel

(toile de fond, décor,

profondeur de champ,

"ça fait partie du paysage")

+

information présentée

sur le mode / la fiction

de l'inédit,

de la

nouveauté,

de la théâtralité

suspense,

effet d'annonce,

focalisation

(mise au premier plan)

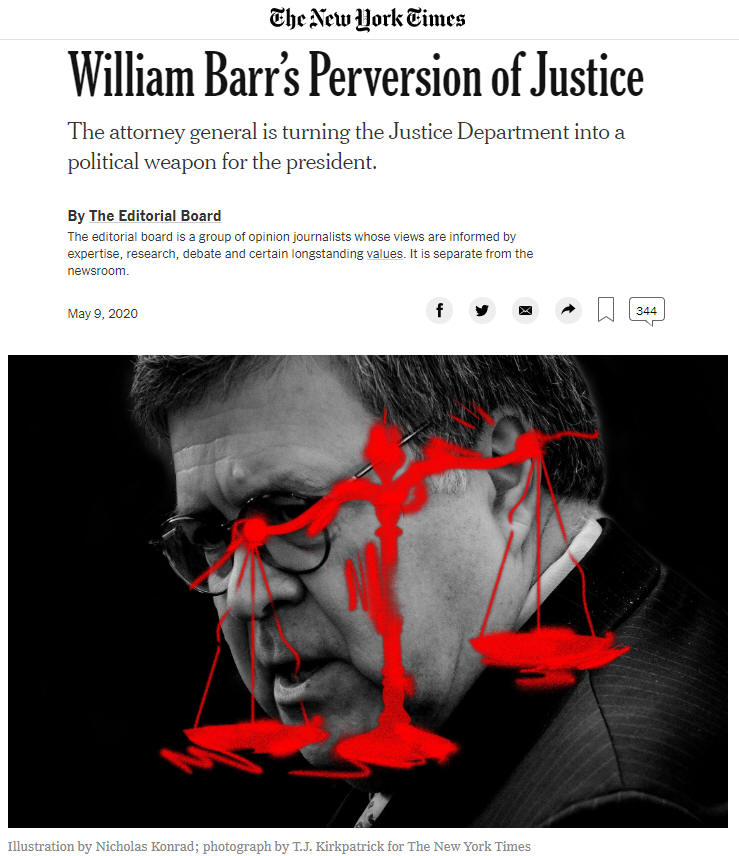

William Barr’s Perversion of

Justice

the UK's

biggest celebration

of

contemporary art

Obama Condemns

Islamic

State’s Killing of Peter Kassig

The Guardian

Culture Hot Spots p. 5

2 September 2006

The Guardian

pp. 8-9 6 July 2006

Obama Condemns

Islamic State’s Killing of Peter Kassig

NOV. 16, 2014

The New York Times

By RUKMINI CALLIMACHI

GAZIANTEP, Turkey — Islamic State militants released a chilling

videotape on Sunday showing they had beheaded a fifth Western hostage, an

American aid worker the group had threatened to kill in retaliation for

airstrikes carried out by the United States in Iraq and Syria.

President Obama on Sunday confirmed the death of the aid worker, Peter Kassig, a

former Army Ranger who disappeared more than a year ago at a checkpoint in

northeastern Syria while delivering medical supplies.

Mr. Kassig “was taken from us in an act of pure evil by a terrorist group,” Mr.

Obama said in a statement from aboard Air Force One that was read to the news

media in Washington.

In recent days, American intelligence agencies received strong indications that

the Islamic State had killed Mr. Kassig, the group’s third American victim. The

president’s announcement was the first official confirmation of his death.

“Today we offer our prayers and condolences to the parents and family of

Abdul-Rahman Kassig, also known to us as Peter,” Mr. Obama’s statement said. The

president used the Muslim name that Mr. Kassig adopted after his capture, making

the point that the Islamic State had killed a fellow Muslim. He acknowledged the

“anguish at this painful time” felt by Mr. Kassig’s family.

The footage in the video released Sunday was of poorer quality than some of the

group’s previous, slickly produced execution videos.

The video shows a black-robed executioner standing over the severed head of Mr.

Kassig. Though the end result of the footage was grimly familiar, it was

strikingly different from the executions of four other Western hostages, whose

recorded deaths were carefully choreographed.

In the clip released early Sunday, the Islamic State displays the head of Mr.

Kassig, 26, at the feet of a man with a British accent who appeared in the

previous beheading videos and has been nicknamed Jihadi John by the British news

media. Unlike the earlier videos, which were staged with multiple cameras from

different vantage points, and which show the hostages kneeling, then uttering

their last words, the footage of Mr. Kassig’s death is curtailed — showing only

the final scene.

“This is Peter Edward Kassig, a U.S. citizen of your country. Peter, who fought

against the Muslims in Iraq while serving as a soldier under the American Army,

doesn’t have much to say. His previous cellmates have already spoken on his

behalf,” the fighter with a British accent says in the video. “You claim to have

withdrawn from Iraq four years ago. We said to you then that you are liars.”

Analysts said that the change in the videos suggested that something may have

gone wrong as the militants, who have been under sustained attack from a United

States-led military coalition and have faced a series of setbacks in recent

weeks, carried out the killing.

“The most obvious difference is in the beheading itself — the previous videos

all showed the beheading on camera,” said Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, a senior

fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, in Washington, and a former

director of the Center for the Study of Terrorist Radicalization. “This one just

shows the severed head itself. I don’t think this was the Islamic State’s

choice.” He added, “The likeliest possibility is that something went wrong when

they were beheading him.”

Among the things that could have gone wrong, analysts surmise, is that the

extremists did not have as much time outdoors as they did when they killed the

others. The United States announced soon after the first beheading in August

that they would send surveillance aircraft over Syria and residents contacted on

social media have reported seeing objects in the sky that they believe are

drones.

The first four beheadings were carried out in the open air, with a cinematic

precision that suggests multiple takes, filmed over an extended period of time.

Carrying out a similar level of production as surveillance planes crisscrossed

the skies above would result in extended exposure — heightening risk.

Another possibility, Mr. Gartenstein-Ross said, is that Mr. Kassig resisted,

depriving the militants of the ability to stage the killing as they wanted.

“We know that this is a very media-savvy organization, and they know that you

only have one take to get the beheading right,” he said.

An Indianapolis native, Mr. Kassig turned to humanitarian work after a tour as

an Army Ranger in Iraq in 2007. He was certified as an emergency technician, and

by 2012 he returned to the battlefield, this time helping bandage the victims of

Syria’s civil war who were flooding into Lebanon. He moved to Lebanon’s capital,

Beirut, where he founded a small aid group and initially used his savings to buy

supplies, like diapers, which he distributed to the Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

In the summer of 2013, he relocated to Gaziantep in southern Turkey, roughly an

hour from the border, and began making regular trips into Syria to offer medical

care to the wounded.

He disappeared on Oct. 1, 2013, when the ambulance he and a colleague were

driving was stopped at a checkpoint on the road to Deir al-Zour, Syria. He was

transferred late last year to a prison beneath the basement of the Children’s

Hospital in Aleppo, and then to a network of jails in Raqqa, the capital of the

extremist group’s self-declared caliphate, where he became one of at least 23

Western hostages held by the group.

His cellmates included two American journalists, James Foley and Steven J.

Sotloff, as well as two British aid workers, David Haines and Alan Henning, who

were beheaded in roughly two-week intervals starting in August. Mr. Kassig was

shown in the video released in October that showed the decapitation of Mr.

Henning.

The previous videos of beheadings produced by the Islamic State, also known as

ISIS or ISIL, appeared to be filmed in the same location, identified by analysts

using geo-mapping as a bald hill outside Raqqa. Each video was relatively short

— under five minutes on average — and included a speech by the hostage, in which

he is forced to accuse his government of crimes against Muslims, while the

masked killer stands by holding the knife.

By contrast, Mr. Kassig’s death appears in the final segment of a nearly

16-minute video, which traces the history of the Islamic State, from its origins

as a unit under the control of Osama bin Laden to its modern incarnation in the

region straddling Iraq and Syria. In one extended sequence, a mass beheading of

captured Syrian soldiers is shown, filmed with long close-ups of details, like

the shining blade of the executioner’s knife, mirroring the high production

quality of the first four beheading videos.

The part showing Mr. Kassig’s body is amateurish compared with both the footage

of the soldiers being killed and previous executions of Westerners.

“The final Kassig execution section is definitely different from previous

videos,” said Jarret Brachman, a counterterrorism expert who advises the United

States intelligence community. The “message to President Obama from Jihadi John

is sloppy, jumbled and redundant. His joke about Kassig having nothing to say

seems like a defensive way of covering up the fact that they don’t have a video

of his actual beheading or weren’t able to make one.”

In the months leading up to his death, Mr. Kassig seemed to know the end was

near.

In a letter to his parents smuggled out this summer, he described his fear: “I

am obviously pretty scared to die but the hardest part is not knowing,

wondering, hoping, and wondering if I should even hope at all,” he wrote. “Just

know I’m with you. Every stream, every lake, every field and river. In the woods

and in the hills, in all the places you showed me. I love you.”

Correction: November 16, 2014

An earlier version of this article misidentified the country where Peter Kassig

went in 2012 to help care for those wounded in and those living as refugees from

Syria’s civil war. It is Lebanon, not Libya.

Karam Shoumali contributed reporting from Gaziantep, Turkey, and Michael S.

Schmidt from Washington.

A version of this article appears in print on November 17, 2014, on page A1 of

the New York edition with the headline: Obama Confirms That ISIS Killed Third

American.

Obama Condemns Islamic State’s Killing of

Peter Kassig,

NYT,

16.11.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/17/world/middleeast/

peter-kassig-isis-video-execution.html

Related

Kitty Empire's artist of the week

https://www.theguardian.com/music/series/

kitty-empires-artist-of-the-week

Alexis Petridis's album of the week

https://www.theguardian.com/music/series/

alexis-petridis-album-of-the-week

Mark Kermode's film of the week

https://www.theguardian.com/film/series/

mark-kermode-film-of-the-week

Voir aussi > Anglonautes >

Grammaire anglais

explicative - niveau avancé

formes nominales

formes nominales > pronoms

|