|

History > 2013 > USA > Education (I)

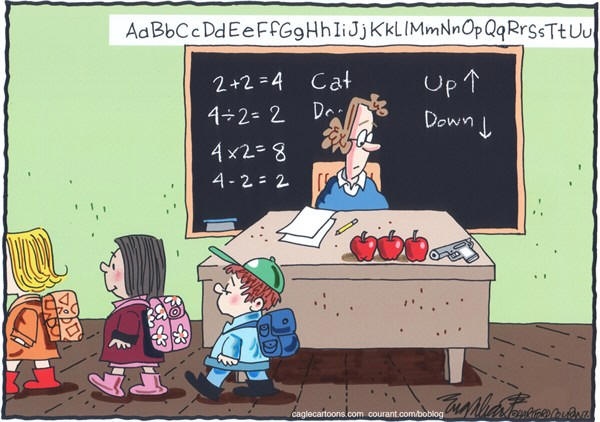

Guns In The Classroom

Bob Englehart

is the staff cartoonist for the Hartford Courant,

and his cartoons are nationally syndicated by Cagle Cartoons.

Cagle

23 January 2013

No Rich Child Left Behind

April 27,

2013

6:15 pm

The New York Times

By SEAN F. REARDON

Here’s a

fact that may not surprise you: the children of the rich perform better in

school, on average, than children from middle-class or poor families. Students

growing up in richer families have better grades and higher standardized test

scores, on average, than poorer students; they also have higher rates of

participation in extracurricular activities and school leadership positions,

higher graduation rates and higher rates of college enrollment and completion.

Whether you think it deeply unjust, lamentable but inevitable, or obvious and

unproblematic, this is hardly news. It is true in most societies and has been

true in the United States for at least as long as we have thought to ask the

question and had sufficient data to verify the answer.

What is news is that in the United States over the last few decades these

differences in educational success between high- and lower-income students have

grown substantially.

One way to see this is to look at the scores of rich and poor students on

standardized math and reading tests over the last 50 years. When I did this

using information from a dozen large national studies conducted between 1960 and

2010, I found that the rich-poor gap in test scores is about 40 percent larger

now than it was 30 years ago.

To make this trend concrete, consider two children, one from a family with

income of $165,000 and one from a family with income of $15,000. These incomes

are at the 90th and 10th percentiles of the income distribution nationally,

meaning that 10 percent of children today grow up in families with incomes below

$15,000 and 10 percent grow up in families with incomes above $165,000.

In the 1980s, on an 800-point SAT-type test scale, the average difference in

test scores between two such children would have been about 90 points; today it

is 125 points. This is almost twice as large as the 70-point test score gap

between white and black children. Family income is now a better predictor of

children’s success in school than race.

The same pattern is evident in other, more tangible, measures of educational

success, like college completion. In a study similar to mine, Martha J. Bailey

and Susan M. Dynarski, economists at the University of Michigan, found that the

proportion of students from upper-income families who earn a bachelor’s degree

has increased by 18 percentage points over a 20-year period, while the

completion rate of poor students has grown by only 4 points.

In a more recent study, my graduate students and I found that 15 percent of

high-income students from the high school class of 2004 enrolled in a highly

selective college or university, while fewer than 5 percent of middle-income and

2 percent of low-income students did.

These widening disparities are not confined to academic outcomes: new research

by the Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam and his colleagues shows

that the rich-poor gaps in student participation in sports, extracurricular

activities, volunteer work and church attendance have grown sharply as well.

In San Francisco this week, more than 14,000 educators and education scholars

have gathered for the annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association. The theme this year is familiar: Can schools provide children a way

out of poverty?

We are still talking about this despite decades of clucking about the crisis in

American education and wave after wave of school reform.Whatever we’ve been

doing in our schools, it hasn’t reduced educational inequality between children

from upper- and lower-income families.

Part of knowing what we should do about this is understanding how and why these

educational disparities are growing. For the past few years, alongside other

scholars, I have been digging into historical data to understand just that. The

results of this research don’t always match received wisdom or playground

folklore.

The most potent development over the past three decades is that the test scores

of children from high-income families have increased very rapidly. Before 1980,

affluent students had little advantage over middle-class students in academic

performance; most of the socioeconomic disparity in academics was between the

middle class and the poor. But the rich now outperform the middle class by as

much as the middle class outperform the poor. Just as the incomes of the

affluent have grown much more rapidly than those of the middle class over the

last few decades, so, too, have most of the gains in educational success accrued

to the children of the rich.

Before we can figure out what’s happening here, let’s dispel a few myths.

The income gap in academic achievement is not growing because the test scores of

poor students are dropping or because our schools are in decline. In fact,

average test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the

so-called Nation’s Report Card, have been rising — substantially in math and

very slowly in reading — since the 1970s. The average 9-year-old today has math

skills equal to those her parents had at age 11, a two-year improvement in a

single generation. The gains are not as large in reading and they are not as

large for older students, but there is no evidence that average test scores have

declined over the last three decades for any age or economic group.

The widening income disparity in academic achievement is not a result of

widening racial gaps in achievement, either. The achievement gaps between blacks

and whites, and Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites have been narrowing slowly over

the last two decades, trends that actually keep the yawning gap between higher-

and lower-income students from getting even wider. If we look at the test scores

of white students only, we find the same growing gap between high- and

low-income children as we see in the population as a whole.

It may seem counterintuitive, but schools don’t seem to produce much of the

disparity in test scores between high- and low-income students. We know this

because children from rich and poor families score very differently on school

readiness tests when they enter kindergarten, and this gap grows by less than 10

percent between kindergarten and high school. There is some evidence that

achievement gaps between high- and low-income students actually narrow during

the nine-month school year, but they widen again in the summer months.

That isn’t to say that there aren’t important differences in quality between

schools serving low- and high-income students — there certainly are — but they

appear to do less to reinforce the trends than conventional wisdom would have us

believe.

If not the usual suspects, what’s going on? It boils down to this: The academic

gap is widening because rich students are increasingly entering kindergarten

much better prepared to succeed in school than middle-class students. This

difference in preparation persists through elementary and high school.

My research suggests that one part of the explanation for this is rising income

inequality. As you may have heard, the incomes of the rich have grown faster

over the last 30 years than the incomes of the middle class and the poor. Money

helps families provide cognitively stimulating experiences for their young

children because it provides more stable home environments, more time for

parents to read to their children, access to higher-quality child care and

preschool and — in places like New York City, where 4-year-old children take

tests to determine entry into gifted and talented programs — access to preschool

test preparation tutors or the time to serve as tutors themselves.

But rising income inequality explains, at best, half of the increase in the

rich-poor academic achievement gap. It’s not just that the rich have more money

than they used to, it’s that they are using it differently. This is where things

get really interesting.

High-income families are increasingly focusing their resources — their money,

time and knowledge of what it takes to be successful in school — on their

children’s cognitive development and educational success. They are doing this

because educational success is much more important than it used to be, even for

the rich.

With a college degree insufficient to ensure a high-income job, or even a job as

a barista, parents are now investing more time and money in their children’s

cognitive development from the earliest ages. It may seem self-evident that

parents with more resources are able to invest more — more of both money and of

what Mr. Putnam calls “‘Goodnight Moon’ time” — in their children’s development.

But even though middle-class and poor families are also increasing the time and

money they invest in their children, they are not doing so as quickly or as

deeply as the rich.

The economists Richard J. Murnane and Greg J. Duncan report that from 1972 to

2006 high-income families increased the amount they spent on enrichment

activities for their children by 150 percent, while the spending of low-income

families grew by 57 percent over the same time period. Likewise, the amount of

time parents spend with their children has grown twice as fast since 1975 among

college-educated parents as it has among less-educated parents. The economists

Garey Ramey and Valerie A. Ramey of the University of California, San Diego,

call this escalation of early childhood investment “the rug rat race,” a phrase

that nicely captures the growing perception that early childhood experiences are

central to winning a lifelong educational and economic competition.

It’s not clear what we should do about all this. Partly that’s because much of

our public conversation about education is focused on the wrong culprits: we

blame failing schools and the behavior of the poor for trends that are really

the result of deepening income inequality and the behavior of the rich.

We’re also slow to understand what’s happening, I think, because the nature of

the problem — a growing educational gap between the rich and the middle class —

is unfamiliar. After all, for much of the last 50 years our national

conversation about educational inequality has focused almost exclusively on

strategies for reducing inequalities between the educational successes of the

poor and the middle class, and it has relied on programs aimed at the poor, like

Head Start and Title I.

We’ve barely given a thought to what the rich were doing. With the exception of

our continuing discussion about whether the rising costs of higher education are

pricing the middle class out of college, we don’t have much practice talking

about what economists call “upper-tail inequality” in education, much less

success at reducing it.

Meanwhile, not only are the children of the rich doing better in school than

even the children of the middle class, but the changing economy means that

school success is increasingly necessary to future economic success, a worrisome

mutual reinforcement of trends that is making our society more socially and

economically immobile.

We need to start talking about this. Strangely, the rapid growth in the

rich-poor educational gap provides a ray of hope: if the relationship between

family income and educational success can change this rapidly, then it is not an

immutable, inevitable pattern. What changed once can change again. Policy

choices matter more than we have recently been taught to think.

So how can we move toward a society in which educational success is not so

strongly linked to family background? Maybe we should take a lesson from the

rich and invest much more heavily as a society in our children’s educational

opportunities from the day they are born. Investments in early-childhood

education pay very high societal dividends. That means investing in developing

high-quality child care and preschool that is available to poor and middle-class

children. It also means recruiting and training a cadre of skilled preschool

teachers and child care providers. These are not new ideas, but we have to stop

talking about how expensive and difficult they are to implement and just get on

with it.

But we need to do much more than expand and improve preschool and child care.

There is a lot of discussion these days about investing in teachers and

“improving teacher quality,” but improving the quality of our parenting and of

our children’s earliest environments may be even more important. Let’s invest in

parents so they can better invest in their children.

This means finding ways of helping parents become better teachers themselves.

This might include strategies to support working families so that they can read

to their children more often.. It also means expanding programs like the

Nurse-Family Partnership that have proved to be effective at helping single

parents educate their children; but we also need to pay for research to develop

new resources for single parents.

It might also mean greater business and government support for maternity and

paternity leave and day care so that the middle class and the poor can get some

of the educational benefits that the early academic intervention of the rich

provides their children. Fundamentally, it means rethinking our still-persistent

notion that educational problems should be solved by schools alone.

The more we do to ensure that all children have similar cognitively stimulating

early childhood experiences, the less we will have to worry about failing

schools. This in turn will enable us to let our schools focus on teaching the

skills — how to solve complex problems, how to think critically and how to

collaborate — essential to a growing economy and a lively democracy.

Sean F.

Reardon

is a professor of education and sociology at Stanford.

No Rich Child Left Behind, NYT, 27.4.2013,

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/no-rich-child-left-behind/

Criminalizing Children at School

April 18, 2013

The New York Times

By THE EDITORIAL BOARD

The National Rifle Association and President Obama responded

to the Newtown, Conn., shootings by recommending that more police officers be

placed in the nation’s schools. But a growing body of research suggests that,

contrary to popular wisdom, a larger police presence in schools generally does

little to improve safety. It can also create a repressive environment in which

children are arrested or issued summonses for minor misdeeds — like cutting

class or talking back — that once would have been dealt with by the principal.

Stationing police in schools, while common today, was virtually unknown during

the 1970s. Things began to change with the surge of juvenile crime during the

’80s, followed by an overreaction among school officials. Then came the 1999

Columbine High School shooting outside Denver, which prompted a surge in

financing for specially trained police. In the mid-1970s, police patrolled about

1 percent of schools. By 2008, the figure was 40 percent.

The belief that police officers automatically make schools safer was challenged

in a 2011 study that compared federal crime data of schools that had police

officers with schools that did not. It found that the presence of the officers

did not drive down crime. The study — by Chongmin Na of The University of

Houston, Clear Lake, and Denise Gottfredson of the University of Maryland — also

found that with police in the buildings, routine disciplinary problems began to

be treated as criminal justice problems, increasing the likelihood of arrests.

Children as young as 12 have been treated as criminals for shoving matches and

even adolescent misconduct like cursing in school. This is worrisome because

young people who spend time in adult jails are more likely to have problems with

law enforcement later on. Moreover, federal data suggest a pattern of

discrimination in the arrests, with black and Hispanic children more likely to

be affected than their white peers.

In Texas, civil rights groups filed a federal complaint against the school

district in the town of Bryan. The lawyers say African-American students are

four times as likely as other students to be charged with misdemeanors, which

can carry fines up to $500 and lead to jail time for disrupting class or using

foul language.

The criminalization of misbehavior so alarmed the New York City Council that, in

2010, it passed the Student Safety Act, which requires detailed police reports

on which students are arrested and why. (Data from the 2011-12 school year show

that black students are being disproportionately arrested and suspended.)

Some critics now want to require greater transparency in the reporting process

to make the police even more forthcoming. Elsewhere in the country, judges,

lawmakers and children’s advocates have been working hard to dismantle what they

have begun to call the school-to-prison pipeline.

Given the growing criticism, districts that have gotten along without police

officers should think twice before deploying them in school buildings.

Criminalizing Children at School, NYT,

18.4.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/19/opinion/criminalizing-children-at-school.html

Scandal in Atlanta

Reignites Debate Over Tests’ Role

April 2,

2013

The New

York Times

By MOTOKO RICH

There are

few more contentious issues in public education than the increased reliance on

standardized testing.

In the context of a fiery debate, the Atlanta school cheating scandal, the

largest in recent history, detonates like a bomb, fueling critics who say that

standardized testing as a way to measure student achievement should be scaled

back.

Evidence of systemic cheating has emerged in as many as a dozen places across

the country, and protests in Chicago, New York City, Seattle, across Texas and

elsewhere represent a growing backlash among educators and parents against

high-stakes testing.

“The widespread cheating and test score manipulation problem,” said Robert

Schaeffer, the public education director of FairTest, the National Center for

Fair and Open Testing, “is one more example of the ways politicians’ fixation on

high-stakes testing is damaging education quality and equity.”

But those who say that testing helps improve the accountability of schools and

teachers argue that focusing on the cheating scandals ignores the larger

picture.

Abandoning testing would “be equivalent to saying ‘O.K., because there are some

players that cheated in Major League Baseball, we should stop keeping score,

because that only encourages people to take steroids,’ ” said Thomas J. Kane,

director of the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, who

has received funding from the Gates Foundation.

In Atlanta, where some critics say the rampant cheating on state tests

invalidates the district’s accomplishments over the past decade, students there

showed more growth between 2003 and 2011, as measured by federal education

exams, than any other district that participated in the tests, including

Chicago, Los Angeles and New York.

Education experts on both sides of the standardized testing debate generally

accept these federal exams, known as the National Assessment of Educational

Progress, as the gold standard in measuring genuine student achievement. The

federal tests were not implicated in the Atlanta investigation.

No one is defending the cheating in Atlanta, which resulted in the indictments

of 35 educators, including the district superintendent. But some education

advocates say the scandal, in a district of mostly black and poor children,

could detract from a genuine effort to raise the quality of education for some

of the neediest students.

“The idea that a superintendent who says, ‘We’ve got to have our kids learning

more and I don’t want to hear excuses about your lack of progress’ is somehow a

bad thing is, I think, unfortunate,” said Kati Haycock, president of the

Education Trust, a nonprofit group that works to close achievement gaps for

racial minorities and low-income children. She added that the tests generally

evaluated fundamental literacy and math skills. “We do know that kids who don’t

know what’s on these very basic tests will not be able to succeed,” Ms. Haycock

said.

Much of the objection to standardized testing is related to the use of student

scores in evaluating teachers. But many states are adopting systems where test

scores are just a part of an educator’s performance review. They are also judged

on classroom observations and, in some cases, student surveys.

Still, critics argue that because the tests provide administrators and state

education departments with the most convenient way to provide a quick

performance snapshot, the tests have warped classrooms by forcing teachers to

narrow their focus.

“The curriculum is focused on test drill,” said Melissa McCann Cooper, a

seventh-grade English teacher at Murchison Middle School in Austin, Tex., where

she said the district dictated a writing program that targeted expository and

persuasive essays, because that was what was tested. “I have some very gifted

writers who are being shoved into a very narrow kind of writing,” Ms. Cooper

said.

There is evidence that teachers who consistently help improve students’

standardized test scores can affect more than immediate academic performance,

with students in those classes being likelier to attend college and earn more as

adults. Teachers and parents argue, though, that the tests often do not

accommodate students who learn differently, or let them demonstrate their

knowledge creatively.

What’s more, testing opponents complain that standardized tests do not measure

all the skills that students need to succeed in college or in jobs, and can

force schools to disregard nontested subjects like art and music.

Such criticism is often loudest in more affluent, high-achieving communities.

“If you’re an upper-middle-class parent in Scarscale and you hate standardized

testing, you have some reason to hate it,” said Michael J. Petrilli, executive

vice president at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, an education policy group.

“It’s probably not doing your kid and your schools a whole lot of good, because

these tests are mainly about raising the floor and putting pressure on the

lowest-performing schools to do better.”

As for cheating, education advocates say states and districts clearly need to

increase security procedures. Matthew M. Chingos, a researcher in the Brown

Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution, points out that states

spend about $1.7 billion a year on testing administration, which represents less

than half 1 percent of total federal, state and local education spending. He

said that states could spend a bit more to hire independent proctors and to make

the tests a better measure of learning.

“If we’re worried about teaching to the test and cheating,” Mr. Chingos said,

“maybe we want to invest in more high-quality assessments that are worthy of

these things that we’re asking of them.”

Scandal in Atlanta Reignites Debate Over Tests’ Role, NYT, 2.4.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/03/education/atlanta-cheating-scandal-reignites-testing-debate.html

The Ivy League Was Another Planet

March 28, 2013

The New

York Times

By CLAIRE VAYE WATKINS

LEWISBURG,

Pa.

IN 12th grade, my friend Ryan and I were finalists for the Silver State

Scholars, a competition to identify the “Top 100” seniors in Nevada. The

finalists were flown to Lake Tahoe for two days of interviews. On the plane,

Ryan and I met a boy from Las Vegas. Looking to size up the competition, we

asked what high school he went to. He said a name we didn’t recognize and added,

“It’s a magnet school.” Ryan asked what a magnet school was, and spent the

remaining hour incredulously demanding a detailed account of the young man’s

educational history: his time abroad, his after-school robotics club, his

tutors, his college prep courses.

All educations, we realized then, are not created equal. For Ryan and me, of

Pahrump, Nev., just an hour from the city, the Vegas boy was a citizen of a

planet we would never visit. What we didn’t know was that there were other, more

distant planets that we could not even see. And those planets couldn’t see us,

either.

A study released last week by researchers at Harvard and Stanford quantified

what everyone in my hometown already knew: even the most talented rural poor

kids don’t go to the nation’s best colleges. The vast majority, the study found,

do not even try.

For deans of admissions brainstorming what they can do to remedy this, might I

suggest: anything.

By the time they’re ready to apply to colleges, most kids from families like

mine — poor, rural, no college grads in sight — know of and apply to only those

few universities to which they’ve incidentally been exposed. Your J.V.

basketball team goes to a clinic at University of Nevada, Las Vegas; you apply

to U.N.L.V. Your Amtrak train rolls through San Luis Obispo, Calif.; you go to

Cal Poly. I took a Greyhound bus to visit high school friends at the University

of Nevada, Reno, and ended up at U.N.R. a year later, in 2003.

If top colleges are looking for a more comprehensive tutorial in recruiting the

talented rural poor, they might take a cue from one institution doing a truly

stellar job: the military.

I never saw a college rep at Pahrump Valley High, but the military made sure

that a stream of alumni flooded back to our school in their uniforms and fresh

flattops, urging their old chums to enlist. Those students who did even

reasonably well on the Asvab (the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery,

for readers who went to schools where this test was not so exhaustively

administered) were thoroughly hounded by recruiters.

My school did its part, too: it devoted half a day’s class time to making sure

every junior took the Asvab. The test was also free, unlike the ACT and SAT,

which I had to choose between because I could afford only one registration fee.

I chose the ACT and crossed off those colleges that asked for the SAT.

To take the SAT II, I had to go to Las Vegas. My mother left work early one

Friday to drive me to my aunt’s house there, so I could sleep over and be at the

testing facility by 7:30 on Saturday morning. (Most of my friends didn’t have

the luxury of an aunt in the city and instead set their alarms for 4:30.) When I

cracked the test booklet, I realized that in registering for the exam with no

guidance, I’d signed up for the wrong subject — Mathematics Level 2, though I’d

barely made it out of algebra alive. Even if I had had the money to retake the

test, I wouldn’t have had another ride to Vegas. So I struggled through it and

said goodbye to those colleges that required the SAT II.

But the most important thing the military did was walk kids and their families

through the enlistment process.

Most parents like mine, who had never gone to college, were either intimidated

or oblivious (and sometimes outright hostile) to the intricacies of college

admissions and financial aid. I had no idea what I was doing when I applied.

Once, I’d heard a volleyball coach mention paying off her student loans, and

this led me to assume that college was like a restaurant — you paid when you

were done. When I realized I needed my mom’s and my stepfather’s income

information and tax documents, they refused to give them to me. They were, I

think, ashamed.

Eventually, I just stole the documents and forged their signatures. (Like nearly

every one of the dozen or so kids who went on to college from my class at

P.V.H.S., I paid for it with the $10,000 Nevada Millennium Scholarship, financed

by Nevada’s share of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.)

Granted, there’s a good reason top colleges aren’t sending recruiters around the

country to woo kids like me and Ryan (who, incidentally, got his B.S. at U.N.R.

before going on to earn his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from Purdue and now

holds a prestigious postdoctoral fellowship with the National Research Council).

The Army needs every qualified candidate it can get, while competitive colleges

have far more applicants than they can handle. But if these colleges are truly

committed to diversity, they have to start paying attention to the rural poor.

Until then, is it any wonder that students in Pahrump and throughout rural

America are more likely to end up in Afghanistan than at N.Y.U.?

Claire Vaye

Watkins, an assistant professor of English at Bucknell,

is the author

of the short story collection “Battleborn.”

The Ivy League Was Another Planet, NYT, 28.3.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/29/opinion/elite-colleges-are-as-foreign-as-mars.html

Better

Colleges Failing to Lure Talented Poor

March 16,

2013

The New York Times

By DAVID LEONHARDT

Most

low-income students who have top test scores and grades do not even apply to the

nation’s best colleges, according to a new analysis of every high school student

who took the SAT in a recent year.

The pattern contributes to widening economic inequality and low levels of

mobility in this country, economists say, because college graduates earn so much

more on average than nongraduates do. Low-income students who excel in high

school often do not graduate from the less selective colleges they attend.

Only 34 percent of high-achieving high school seniors in the bottom fourth of

income distribution attended any one of the country’s 238 most selective

colleges, according to the analysis, conducted by Caroline M. Hoxby of Stanford

and Christopher Avery of Harvard, two longtime education researchers. Among top

students in the highest income quartile, that figure was 78 percent.

The findings underscore that elite public and private colleges, despite a stated

desire to recruit an economically diverse group of students, have largely failed

to do so.

Many top low-income students instead attend community colleges or four-year

institutions closer to their homes, the study found. The students often are

unaware of the amount of financial aid available or simply do not consider a top

college because they have never met someone who attended one, according to the

study’s authors, other experts and high school guidance counselors.

“A lot of low-income and middle-income students have the inclination to stay

local, at known colleges, which is understandable when you think about it,” said

George Moran, a guidance counselor at Central Magnet High School in Bridgeport,

Conn. “They didn’t have any other examples, any models — who’s ever heard of

Bowdoin College?”

Whatever the reasons, the choice frequently has major consequences. The colleges

that most low-income students attend have fewer resources and lower graduation

rates than selective colleges, and many students who attend a local college do

not graduate. Those who do graduate can miss out on the career opportunities

that top colleges offer.

The new study is beginning to receive attention among scholars and college

officials because it is more comprehensive than other research on college

choices. The study suggests that the problems, and the opportunities, for

low-income students are larger than previously thought.

“It’s pretty close to unimpeachable — they’re drawing on a national sample,”

said Tom Parker, the dean of admissions at Amherst College, which has

aggressively recruited poor and middle-class students in recent years. That so

many high-achieving, lower-income students exist “is a very important

realization,” Mr. Parker said, and he suggested that colleges should become more

creative in persuading them to apply.

Top low-income students in the nation’s 15 largest metropolitan areas do often

apply to selective colleges, according to the study, which was based on test

scores, self-reported data, and census and other data for the high school class

of 2008. But such students from smaller metropolitan areas — like Bridgeport;

Memphis; Sacramento; Toledo, Ohio; and Tulsa, Okla. — and rural areas typically

do not.

These students, Ms. Hoxby said, “lack exposure to people who say there is a

difference among colleges.”

Elite colleges may soon face more pressure to recruit poor and middle-class

students, if the Supreme Court restricts race-based affirmative action. A ruling

in the case, involving the University of Texas, is expected sometime before late

June.

Colleges currently give little or no advantage in the admissions process to

low-income students, compared with more affluent students of the same race,

other research has found. A broad ruling against the University of Texas

affirmative action program could cause colleges to take into account various

socioeconomic measures, including income, neighborhood and family composition.

Such a step would require an increase in these colleges’ financial aid spending

but would help them enroll significant numbers of minority students.

Among high-achieving, low-income students, 6 percent were black, 8 percent

Latino, 15 percent Asian-American and 69 percent white, the study found.

“If there are changes to how we define diversity,” said Greg W. Roberts, the

dean of admission at the University of Virginia, referring to the court case,

“then I expect schools will really work hard at identifying low-income

students.”

Ms. Hoxby and Mr. Avery, both economists, compared the current approach of

colleges to looking under a streetlight for a lost key. The institutions

continue to focus their recruiting efforts on a small subset of high schools in

cities like Boston, New York and Los Angeles that have strong low-income

students.

The researchers defined high-achieving students as those very likely to gain

admission to a selective college, which translated into roughly the top 4

percent nationwide. Students needed to have at least an A-minus average and a

score in the top 10 percent among students who took the SAT or the ACT.

Of these high achievers, 34 percent came from families in the top fourth of

earners, 27 percent from the second fourth, 22 percent from the third fourth and

17 percent from the bottom fourth. (The researchers based the income cutoffs on

the population of families with a high school senior living at home, with

$41,472 being the dividing line for the bottom quartile and $120,776 for the

top.)

Winona Leon, a sophomore at the University of Southern California who grew up in

West Texas, said she was not surprised by the study’s results. Ms. Leon was the

valedictorian of her 17-member senior class in the ranch town of Fort Davis,

where Advanced Placement classes and SAT preparation were rare.

“It was really on ourselves to create those resources,” she said.

She first assumed that faraway colleges would be too expensive, given their high

list prices and the cost of plane tickets home. But after receiving a mailing

from QuestBridge, an outreach program for low-income students, she came to

realize that a top college might offer her enough financial aid to make it less

expensive than a state university in Texas.

On average, private colleges and top state universities are substantially more

expensive than community colleges, even with financial aid. But some colleges,

especially the most selective, offer enough aid to close or eliminate the gap

for low-income students.

If they make it to top colleges, high-achieving, low-income students tend to

thrive there, the paper found. Based on the most recent data, 89 percent of such

students at selective colleges had graduated or were on pace to do so, compared

with only 50 percent of top low-income students at nonselective colleges.

The study will be published in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

The authors emphasized that their data did not prove that students not applying

to top colleges would apply and excel if colleges recruited them more heavily.

Ms. Hoxby and Sarah Turner, a University of Virginia professor, are conducting

follow-up research in which they perform random trials to evaluate which

recruiting techniques work and how the students subsequently do.

For colleges, the potential recruiting techniques include mailed brochures,

phone calls, e-mail, social media and outreach from alumni. Another recent

study, cited in the Hoxby-Avery paper, suggests that very selective colleges

have at least one graduate in the “vast majority of U.S. counties.”

Better Colleges Failing to Lure Talented Poor, NYT, 16.3.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/17/education/

scholarly-poor-often-overlook-better-colleges.html

A State Backs Guns in Class for Teachers

March 8, 2013

The New York Times

By JOHN ELIGON

South Dakota became the first state in the nation to enact a

law explicitly authorizing school employees to carry guns on the job, under a

measure signed into law on Friday by Gov. Dennis Daugaard.

Passage of the law comes amid a passionate nationwide debate over arming

teachers, stoked after 20 first graders died in an elementary school shooting in

Newtown, Conn., in December. Shortly afterward, the National Rifle Association

proposed a plan for armed security officers in every school, and legislation to

allow school personnel to carry guns was introduced in about two dozen states.

All those measures had stalled until now.

Several other states already have provisions in their laws — or no legal

restrictions — that make it possible for teachers to possess guns in the

classroom. In fact, a handful of school districts nationwide do have teachers

who carry firearms. But South Dakota is the only known state with a statute that

specifically authorizes teachers to possess a firearm in a K-12 school,

according to Lauren Heintz, a research analyst at the National Conference of

State Legislatures.

Representative Scott Craig, a freshman Republican in the South Dakota House who

sponsored the bill, said he hoped the measure would shift the country’s

discourse on school safety.

“Given the national attention to safety in schools, specifically in response to

tragedies like in Connecticut, this is huge,” he said. He added that, hopefully,

“dominoes will start to fall, people will see it’s reasonable, it’s safer than

they think, it’s proactive and it’s preventive.”

The law leaves it up to school districts to decide whether to allow armed

teachers. It remains to be seen, however, if many schools will permit guns in

classrooms and whether the measure will reverberate nationwide. Mr. Daugaard, a

Republican, said he did not think that many schools would take advantage of the

option, but that it was important for them to have the choice available.

While many gun control advocates are horrified by the notion of guns in schools,

Laura Cutilletta, a senior staff lawyer with the San Francisco-based Law Center

to Prevent Gun Violence, said that what South Dakota did would not spark a

national trend. “For South Dakota to do this is less of a concern than if we saw

it in Colorado or somewhere else like that,” she said, referring to states that

have advocated for gun-control legislation.

Andrew Arulanandam, a spokesman for the National Rifle Association, said the

group supported the bill and lobbied for it in the South Dakota Legislature.

“There’s certainly not a one-size-fits-all approach to keeping our children safe

in schools,” he said. “It’s incumbent upon state and local governments to

formulate and implement a plan to keep students safe.”

The law says that school districts may choose to allow a school employee, a

hired security officer or a volunteer to serve as a “sentinel” who can carry a

firearm in the school. The school district must receive the permission of its

local law enforcement agency before carrying out the program. The law requires

the sentinels to undergo training similar to what law enforcement officers

receive.

“I think it does provide the same safety precautions that a citizen expects when

a law enforcement officer enters onto a premises,” Mr. Daugaard said in an

interview. He added that this law was more restrictive than those in other

states that permit guns in schools.

South Dakota is a state with deep roots in hunting, where children start

learning how to shoot BB guns when they are 8, skeet shoot with shotguns by age

14 and enter target shooting contests with .22-caliber semiautomatic rifles.

“Our kids start hunting here when they’re preteens,” said Kevin Jensen, who

supports the bill and is the vice president of the Canton School Board in South

Dakota. “We know guns. We respect guns.”

Opponents, which included state associations representing school boards and

teachers, said the bill was rushed, did not make schools safer and ignored other

approaches to safety.

Wade Pogany, the executive director of the Associated School Boards of South

Dakota, said he believed more discussion was necessary before passing this bill.

“If firearms are the best option that we have, I’ll stand down,” Dr. Pogany

said. “But let’s not come into a heated, emotional debate about this and say

this is the answer. This is premature.”

Supporters say the measure is important in a state where some schools are many

miles away from emergency responders, who can take upward of 30 or 45 minutes to

reach some areas.

But Don Kirkegaard, the superintendent of the Meade School District, which

encompasses 11 schools over 3,200 square miles, said that although some of his

institutions were isolated, he did not see any evidence to suggest that they

would be safer if teachers were armed. Mr. Kirkegaard said that schools in more

populated areas have been most affected by shootings.

“The likelihood of it happening in our rural attendant centers is not nearly as

probable as it is in the urban city areas,” he said.

But his school district, like many others across the state and country, does

employ an armed “resource officer” affiliated with the police who bounces

between the schools. Opponents of the legislation said they would be more

comfortable with providing resources to districts so they could hire law

enforcement to protect the schools.

It is unclear how many school districts nationwide have teachers carrying guns.

Hawaii and New Hampshire do not have any prohibition against carrying weapons on

school property for those with concealed carry permits. Texas’s law against

carrying weapons in school includes an exemption for people whom the school

authorizes.

The Harrold Independent School District in Texas began allowing teachers to

carry weapons in 2008. Utah is also said to have teachers who carry guns in the

classroom, though they do not have to disclose it publicly. Supporters point out

that there have been no accidents in states where teachers do carry guns.

But a couple of recent episodes could leave some people unsettled about firearms

in schools.

A maintenance worker at an East Texas school that plans to allow its staff to

carry guns accidentally shot himself during firearms safety training last month.

And a police officer assigned to patrol a high school in a town north of New

York City after the Newtown shooting was suspended this week because he

accidentally fired his gun in the hallway during school hours.

A State Backs Guns in Class for Teachers,

NYT, 8.3.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/09/us/south-dakota-gun-law-classrooms.html

Racist Incidents Stun Campus

and Halt

Classes at Oberlin

March 4,

2013

The New York Times

By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA and TRIP GABRIEL

OBERLIN,

Ohio — Oberlin College, known as much for ardent liberalism as for academic

excellence, canceled classes on Monday and convened a “day of solidarity” after

the latest in a monthlong string of what it called hate-related incidents and

vandalism.

At an emotional gathering in the packed 1,200-seat campus chapel, the college

president, Marvin Krislov, apologized on behalf of the college to students who

felt threatened by the incidents and said classes were canceled for “a different

type of educational exercise,” one intended to hold “an honest discussion, even

a difficult discussion.”

In the last month, racist, anti-Semitic and antigay messages have been left

around campus, a jarring incongruity in a place with the liberal political

leanings and traditions of Oberlin, a school of 2,800 students in Ohio, about 30

miles southwest of Cleveland. Guides to colleges routinely list it as among the

most progressive, activist and gay-friendly schools in the country.

The incidents included slurs written on Black History Month posters, drawings of

swastikas and the message “Whites Only” scrawled above a water fountain. After

midnight on Sunday, someone reported seeing a person dressed in a white robe and

hood near the Afrikan Heritage House. Mr. Krislov and three deans announced the

sighting in a community-wide e-mail early Monday morning.

“From what we have seen we believe these actions are the work of a very small

number of cowardly people,” Mr. Krislov told students, declining to give further

details because the campus security department and the Oberlin city police are

investigating.

A college spokesman, Scott Wargo, said investigators had not determined whether

the suspect or suspects were students or from off-campus.

Several students who spoke out at the campuswide meeting criticized the

administration, saying it was not doing enough to create a “safe and inclusive”

environment and was taking action only when prodded by student activists. But

beyond the chapel, many students praised the administration for a decisive

response.

“I was pretty shocked it would happen here,” said Sarah Kahl, a 19-year-old

freshman from Boston. “It’s a little scary.” She said there was an implied

threat behind the incidents. “That’s why this day is so important, so urgent.”

Meredith Gadsby, the chairwoman of the Afrikana Studies department, which hosted

a teach-in at midday attended by about 300 students, said, “Many of our students

feel very frightened, very insecure.”

One purpose of the teach-in was to make students aware of groups that have

formed, some in the past 24 hours in dorms, to respond.

“They’ll be addressing ways to publicly respond to the bias incidents with what

I call positive propaganda, and let people know, whoever the culprits are, that

they’re being watched, and people are taking care of themselves and each other,”

Dr. Gadsby said.

The opinion of many students was that the incidents did not reflect a prevailing

bigotry on campus, and may well be the work of someone just trying to stir

trouble. “It seems to bark worse than it bites,” said Cooper McDonald, a

19-year-old sophomore from Newton, Mass.

“I can’t see many of my classmates — any of my classmates — doing things like

this,” he said. “It doesn’t reflect the town, either.”

He added: “The way the school handled it was awesome. It’s not an angry

response, it’s all very positive.”

The report of a person in a costume meant to evoke the Ku Klux Klan added a more

threatening element than earlier incidents. The convocation with the president

and deans, originally scheduled for Wednesday, was moved overnight, to Monday.

“When it was just graffiti people were alarmed and disturbed. But this is much

more threatening,” said Mim Halpern, 18, a freshman from Toronto.

There were few details of the sighting, which occurred at 1:30 a.m. on Monday,

Mr. Wargo said. The person who reported it was in a car “and came back around

and didn’t see the individual again,” he added.

Anne Trubek, an associate professor in the English department, said that in her

15 years at Oberlin there had been earlier bias incidents but none so

provocative. “They were relatively minor events that would not be a large

hullabaloo elsewhere, but because Oberlin is so attuned to these issues they get

addressed very quickly,” she said.

Founded in 1833, Oberlin was one of the first colleges in the nation to educate

women and men together, and one of the first to admit black students. Before the

Civil War, it was an abolitionist hotbed and an important stop on the

Underground Railroad.

Richard

Pérez-Peña reported from Oberlin,

and Trip

Gabriel from New York.

Racist Incidents Stun Campus and Halt Classes at Oberlin, NYT, 4.3.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/education/

oberlin-cancels-classes-after-series-of-hate-related-incidents.html

The

Trouble With Online College

February

18, 2013

The New York Times

Stanford University ratcheted up interest in online education when a pair of

celebrity professors attracted more than 150,000 students from around the world

to a noncredit, open enrollment course on artificial intelligence. This

development, though, says very little about what role online courses could have

as part of standard college instruction. College administrators who dream of

emulating this strategy for classes like freshman English would be irresponsible

not to consider two serious issues.

First, student attrition rates — around 90 percent for some huge online courses

— appear to be a problem even in small-scale online courses when compared with

traditional face-to-face classes. Second, courses delivered solely online may be

fine for highly skilled, highly motivated people, but they are inappropriate for

struggling students who make up a significant portion of college enrollment and

who need close contact with instructors to succeed.

Online classes are already common in colleges, and, on the whole, the record is

not encouraging. According to Columbia University’s Community College Research

Center, for example, about seven million students — about a third of all those

enrolled in college — are enrolled in what the center describes as traditional

online courses. These typically have about 25 students and are run by professors

who often have little interaction with students. Over all, the center has

produced nine studies covering hundreds of thousands of classes in two states,

Washington and Virginia. The picture the studies offer of the online revolution

is distressing.

The research has shown over and over again that community college students who

enroll in online courses are significantly more likely to fail or withdraw than

those in traditional classes, which means that they spend hard-earned tuition

dollars and get nothing in return. Worse still, low-performing students who may

be just barely hanging on in traditional classes tend to fall even further

behind in online courses.

A five-year study, issued in 2011, tracked 51,000 students enrolled in

Washington State community and technical colleges. It found that those who took

higher proportions of online courses were less likely to earn degrees or

transfer to four-year colleges. The reasons for such failures are well known.

Many students, for example, show up at college (or junior college) unprepared to

learn, unable to manage time and having failed to master basics like math and

English.

Lacking confidence as well as competence, these students need engagement with

their teachers to feel comfortable and to succeed. What they often get online is

estrangement from the instructor who rarely can get to know them directly.

Colleges need to improve online courses before they deploy them widely.

Moreover, schools with high numbers of students needing remedial education

should consider requiring at least some students to demonstrate success in

traditional classes before allowing them to take online courses.

Interestingly, the center found that students in hybrid classes — those that

blended online instruction with a face-to-face component — performed as well

academically as those in traditional classes. But hybrid courses are rare, and

teaching professors how to manage them is costly and time-consuming.

The online revolution offers intriguing opportunities for broadening access to

education. But, so far, the evidence shows that poorly designed courses can

seriously shortchange the most vulnerable students.

The Trouble With Online College, NYT, 18.2.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/19/opinion/the-trouble-with-online-college.html

The Secret to Fixing Bad Schools

February 9,

2013

The New York Times

By DAVID L. KIRP

WHAT would

it really take to give students a first-rate education? Some argue that our

schools are irremediably broken and that charter schools offer the only

solution. The striking achievement of Union City, N.J. — bringing poor, mostly

immigrant kids into the educational mainstream — argues for reinventing the

public schools we have.

Union City makes an unlikely poster child for education reform. It’s a poor

community with an unemployment rate 60 percent higher than the national average.

Three-quarters of the students live in homes where only Spanish is spoken. A

quarter are thought to be undocumented, living in fear of deportation.

Public schools in such communities have often operated as factories for failure.

This used to be true in Union City, where the schools were once so wretched that

state officials almost seized control of them. How things have changed. From

third grade through high school, students’ achievement scores now approximate

the statewide average. What’s more, in 2011, Union City boasted a high school

graduation rate of 89.5 percent — roughly 10 percentage points higher than the

national average. Last year, 75 percent of Union City graduates enrolled in

college, with top students winning scholarships to the Ivies.

As someone who has worked on education policy for four decades, I’ve never seen

the likes of this. After spending a year in Union City working on a book, I

believe its transformation offers a nationwide strategy.

Ask school officials to explain Union City’s success and they start with

prekindergarten, which enrolls almost every 3- and 4-year-old. There’s abundant

research showing the lifetime benefits of early education. Here, seeing is

believing.

One December morning the lesson is making latkes, the potato pancakes that are a

Hanukkah staple. Everything that transpires during these 90 minutes could be

called a “teachable moment” — describing the smell of an onion (“Strong or

light? Strong — duro. Will it smell differently when we cook it? We’ll have to

find out.”); pronouncing the “p” in pepper and pimento; getting the hang of a

food processor (“When I put all the ingredients in, what will happen?”).

Cognitive and noncognitive, thinking and feeling; here, this line vanishes. The

good teacher is always on the lookout for both kinds of lessons, always aiming

to reach both head and heart. “My goal is to do for these kids what I do with my

own children,” the teacher, Susana Rojas, tells me. “It’s all about exposure to

concepts — wide, narrow, long, short. I bring in breads from different

countries. ‘Let’s do a pie chart showing which one you liked the best.’ I don’t

ask them to memorize 1, 2, 3 — I could teach a monkey to count.”

From pre-K to high school, the make-or-break factor is what the Harvard

education professor Richard Elmore calls the “instructional core” — the skills

of the teacher, the engagement of the students and the rigor of the curriculum.

To succeed, students must become thinkers, not just test-takers.

When Alina Bossbaly greets her third grade students, ethics are on her mind.

“Room 210 is a pie — un pie — and each of us is a slice of that pie.” The pie

offers a down-to-earth way of talking about a community where everyone has a

place. Building character and getting students to think is her mission. From Day

1, her kids are writing in their journals, sifting out the meaning of stories

and solving math problems. Every day, Ms. Bossbaly is figuring out what’s best

for each child, rather than batch-processing them.

Though Ms. Bossbaly is a star, her philosophy pervades the district. Wherever I

went, these schools felt less like impersonal institutions than the simulacrum

of an extended family.

UNTIL recently, Union City High bore the scarlet-letter label, “school in need

of improvement.” It has taken strong leadership from its principal, John

Bennetti, to turn things around — to instill the belief that education can be a

ticket out of poverty.

On Day 1, the principal lays out the house rules. Everything is tied to a single

theme — pride and respect in “our house” — that resonates with the community

culture of family, unity and respect. “Cursing doesn’t showcase our talents.

Breaking the dress code means we’re setting a tone that unity isn’t important,

coming in late means missing opportunities to learn.” Bullying is high on his

list of nonnegotiables: “We are about caring and supporting.”

These students sometimes behave like college freshmen, as in a seminar where

they’re parsing Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” They can be boisterously jokey with

their teachers. But there’s none of the note-swapping, gum-chewing,

wisecracking, talking-back rudeness you’d anticipate if your opinions about high

school had been shaped by movies like “Dangerous Minds.”

And the principal is persuading teachers to raise their expectations. “There

should be more courses that prepare students for college, not simply more work

but higher-quality work,” he tells me. This approach is paying off big time:

Last year, in a study of 22,000 American high schools, U.S. News & World Report

and the American Institutes for Research ranked Union City High in the top 22

percent.

What makes Union City remarkable is, paradoxically, the absence of pizazz. It

hasn’t followed the herd by closing “underperforming” schools or giving the boot

to hordes of teachers. No Teach for America recruits toil in its classrooms, and

there are no charter schools.

A quarter-century ago, fear of a state takeover catalyzed a transformation. The

district’s best educators were asked to design a curriculum based on evidence,

not hunch. Learning by doing replaced learning by rote. Kids who came to school

speaking only Spanish became truly bilingual, taught how to read and write in

their native tongue before tackling English. Parents were enlisted in the cause.

Teachers were urged to work together, the superstars mentoring the stragglers

and coaches recruited to add expertise. Principals were expected to become

educational leaders, not just disciplinarians and paper-shufflers.

From a loose confederacy, the schools gradually morphed into a coherent system

that marries high expectations with a “we can do it” attitude. “The real story

of Union City is that it didn’t fall back,” says Fred Carrigg, a key architect

of the reform. “It stabilized and has continued to improve.”

To any educator with a pulse, this game plan sounds so old-school obvious that

it verges on platitude. That these schools are generously financed clearly makes

a difference — not every community will decide to pay for two years of

prekindergarten — but too many districts squander their resources.

School officials flock to Union City and other districts that have beaten the

odds, eager for a quick fix. But they’re on a fool’s errand. These places — and

there are a host of them, largely unsung — didn’t become exemplars by behaving

like magpies, taking shiny bits and pieces and gluing them together. Instead,

each devised a long-term strategy reaching from preschool to high school. Each

keeps learning from experience and tinkering with its model. Nationwide, there’s

no reason school districts — big or small; predominantly white, Latino or black

— cannot construct a system that, like the schools of Union City, bends the arc

of children’s lives.

David L. Kirp

is a professor of public policy

at the

University of California, Berkeley,

and the author

of the forthcoming book

“Improbable

Scholars: The Rebirth of a Great American School System

and a Strategy

for America’s Schools.”

The Secret to Fixing Bad Schools, NYT, 9.2.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/10/opinion/sunday/the-secret-to-fixing-bad-schools.html

Students Disciplined in Harvard Scandal

February 1,

2013

The New York Times

By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA

Harvard has

forced dozens of students to leave in its largest cheating scandal in memory,

the university made clear in summing up the affair on Friday, but it would not

address assertions that the blame rested partly with a professor and his

teaching assistants.

Harvard would not say how many students had been disciplined for cheating on a

take-home final exam given last May in a government class, but the university’s

statements indicated that the number forced out was around 70. The class had 279

students, and Harvard administrators said last summer that “nearly half” were

suspected of cheating and would have their cases reviewed by the Administrative

Board. On Friday, a Harvard dean, Michael D. Smith, wrote in a letter to faculty

members and students that, of those cases, “somewhat more than half” had

resulted in a student’s being required to withdraw.

Dr. Smith, the dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, wrote, “Of the

remaining cases, roughly half the students received disciplinary probation,

while the balance ended in no disciplinary action.” He wrote that the last of

the cases was concluded in December; no explanation was offered for the delay in

making a statement. The forced withdrawals were retroactive to the start of the

school year, he wrote, and those students’ tuition payments would be refunded.

The Administrative Board’s Web site says that forced withdrawals usually last

two to four semesters, after which a student may return.

Howard Gardner, a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education who has

spent much of his career studying cheating, said that eventually, the university

should “give a much more complete account of exactly what happened and why it

happened.”

The episode has given a black eye to one of the world’s great educational

institutions, where in an average year, 17 students are forced out for academic

dishonesty. It was a heavy blow to sports programs, because the class drew a

large number of varsity athletes, some of them on the basketball team. Two

players accused of cheating withdrew in September rather than risk losing a year

of athletic eligibility on a season that disciplinary action could cut short.

People briefed on the investigations say that they went on longer than expected

because the university’s effort was painstaking, hiring additional staff members

to comb through each student’s exam and even color-coding specific words that

appeared in multiple papers.

One implicated student, who argued that similarities between his paper and

others could be traced to shared lecture notes, said the Administrative Board

demanded that he produce the notes six months later. The student, who asked not

to be identified because he still must deal with Harvard administrators, said he

found some notes and was not forced to withdraw.

Some Harvard professors and alumni, along with many students, have protested

that the university was too slow in resolving the cases, too vague about its

ethical standards or too tough on the accused.

Robert Peabody, a lawyer representing two implicated students, said as their

cases dragged on, with frequent postponement, “they emotionally deteriorated

over the course of the semester.” He said one was forced to leave the

university, and the other was placed on academic probation.

While Harvard has not identified the course or the professor involved, they were

quickly identified by the implicated students as Introduction to Congress and

Matthew B. Platt, an assistant professor of government. Dr. Platt did not

respond to messages seeking comment Friday.

In previous years, students called it an easy class with optional attendance and

frequent collaboration. But students who took it last spring said that it had

suddenly become quite difficult, with tests that were hard to comprehend, so

they sought help from the graduate students who ran the class discussion groups

and graded assignments. Those teaching fellows, they said, readily advised them

on interpreting exam questions.

Administrators said that on final-exam questions, some students supplied

identical answers, down to, in some cases, typographical errors, indicating that

they had written them together or plagiarized them. But some students claimed

that the similarities in their answers were due to sharing notes or sitting in

on sessions with the same teaching fellows. The instructions on the take-home

exam explicitly prohibited collaboration, but many students said they did not

think that included talking with teaching fellows.

Dr. Smith’s long note did not say how the Administrative Board viewed such

distinctions, or whether the university had investigated the conduct of the

professor and teaching fellows, and a spokesman said Harvard would not elaborate

on those questions.

Students Disciplined in Harvard Scandal, NYT, 1.2.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/02/education/harvard-forced-dozens-to-leave-in-cheating-scandal.html

More

Lessons About Charter Schools

February 1,

2013

The New York Times

The charter

school movement gained a foothold in American education two decades ago partly

by asserting that independently run, publicly financed schools would outperform

traditional public schools if they were exempted from onerous regulations. The

charter advocates also promised that unlike traditional schools, which were

allowed to fail without consequence, charter schools would be rigorously

reviewed and shut down when they failed to perform.

With thousands of charter schools now operating in 40 states, and more coming

online every day, neither of these promises has been kept. Despite a growing

number of studies showing that charter schools are generally no better — and

often are worse — than their traditional counterparts, the state and local

agencies and organizations that grant the charters have been increasingly

hesitant to shut down schools, even those that continue to perform abysmally for

years on end.

If the movement is to maintain its credibility, the charter authorizers must

shut down failed schools quickly and limit new charters to the most credible

applicants, including operators who have a demonstrated record of success.

That is the clear message of continuing analysis from the Center for Research on

Education Outcomes at Stanford University, which tracks student performance in

25 states. In 2009, its large-scale study showed that only 17 percent of charter

schools provided a better education than traditional schools, and 37 percent

actually offered children a worse education.

A study released this week by the center suggests that the standards used by the

charter authorizers to judge school performance are terribly weak.

It debunked the common notion that it takes a long time to tell whether a new

school can improve student learning. In fact, the study notes, it is pretty

clear after just three years which schools are going to be high performers and

which of them will be mediocre. By that time, the charter authorizers should be

putting troubled schools on notice that they might soon be closed. As the study

notes: “For the majority of schools, poor first year performance will give way

to poor second year performance. Once this has happened, the future is

predictable and extremely bleak. For the students enrolled in these schools,

this is a tragedy that must not be dismissed.”

The same principles should apply to decisions to allow charter school operators

to expand into charter management organizations, which manage several schools

under a single organizational umbrella. Permission to expand should be granted

only if the schools can demonstrate that they can actually improve student

performance.

The study found that minority students and those from poor families fared better

in charter management organizations. For example, the Kipp super-network and the

Uncommon Schools, two large, established networks, have seen “strong and

positive learning gains” for their students.

The study does not explain why these schools perform so well. But the answer is

likely that they closely replicate a successful learning program and they keep

the level of teaching uniformly high. In any case, the researchers and policy

makers need to pay closer attention to how these schools function. For according

to the study, Kipp and the Uncommon Schools have actually managed to eliminate

the learning gap between poor and higher-income students.

Currently, only 6 percent of all schools are charter schools, and charter

networks account for only about one-fifth of that total. States that are in a

hurry to expand charter schools should proceed carefully. The evidence of

success is not all that ample.

More Lessons About Charter Schools, NYT, 1.2.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/02/opinion/

more-lessons-about-charter-schools.html

My Valuable, Cheap College Degree

January 31,

2013

The New York Times

By ARTHUR C. BROOKS

WASHINGTON

MUCH is being written about the preposterously high cost of college. The median

inflation-adjusted household income fell by 7 percent between 2006 and 2011,

while the average real tuition at public four-year colleges increased over that

period by over 18 percent. Meanwhile, the average tuition for just one year at a

four-year private university in 2011 was almost $33,000, according to the

National Center for Education Statistics. College tuition has increased at twice

the rate of health care costs over the past 25 years.

Ballooning student loan debt, an impending college bubble, and a return on the

bachelor’s degree that is flat or falling: all these things scream out for

entrepreneurial solutions.

One idea gaining currency is the $10,000 college degree — the so-called 10K-B.A.

— which apparently was inspired by a challenge to educators from Bill Gates, and

has recently led to efforts to make it a reality by governors in Texas, Florida

and Wisconsin, as well as by a state assemblyman in California.

Most 10K-B.A. proposals rethink the costliest part of higher education — the

traditional classroom teaching. Predictably, this means a reliance on online and

distance-learning alternatives. And just as predictably, this has stimulated

antibodies to unconventional modes of learning. Some critics see it as an

invitation to charlatans and diploma mills. Even supporters often suggest that

this is just an idea to give poor people marginally better life opportunities.

As Darryl Tippens, the provost of Pepperdine University, recently put it, “No

PowerPoint presentation or elegant online lecture can make up for the surprise,

the frisson, the spontaneous give-and-take of a spirited, open-ended dialogue

with another person.” And what happens when you excise those frissons? In the

words of the president of one university faculty association, “You’re going to

be awarding degrees that are worthless to people.”

I disagree. I possess a 10K-B.A., which I got way back in 1994. And it was the

most important intellectual and career move I ever made.

After high school, I spent an unedifying year in college. The year culminated in

money problems, considerably less than a year of credits, and a joint decision

with the school that I should pursue my happiness elsewhere. Next came what my

parents affectionately called my “gap decade,” during which time I made my

living as a musician. By my late 20s I was ready to return to school. But I was

living in Spain, had a thin bank account, and no desire to start my family with

a mountain of student loans.

Fortunately, there was a solution — an institution called Thomas Edison State

College in Trenton, N.J. This is a virtual college with no residence

requirements. It banks credits acquired through inexpensive correspondence

courses from any accredited college or university in America.

I took classes by mail from the University of Washington, the University of

Wyoming, and other schools with the lowest-priced correspondence courses I could

find. My degree required the same number of credits and type of classes that any

student at a traditional university would take. I took the same exams (proctored

at local libraries and graded by graduate students) as in-person students. But I

never met a teacher, never sat in a classroom, and to this day have never laid

eyes on my beloved alma mater.

And the whole degree, including the third-hand books and a sticker for the car,

cost me about $10,000 in today’s dollars.

Now living back in the United States, I followed the 10K-B.A. with a 5K-M.A. at

a local university while working full time, and then endured the standard penury

of being a full-time doctoral fellow in a residential Ph.D. program. The final

tally for a guy in his 30s supporting a family: three degrees, zero debt.

Did I earn a worthless degree? Hardly. My undergraduate years may have been

bereft of frissons, but I wound up with a career as a tenured professor at

Syracuse University, a traditional university. I am now the president of a

Washington research organization.

Not surprisingly, my college experience has occasionally been the target of

ridicule. It is true that I am no Harvard Man. But I can say with full

confidence that my 10K-B.A. is what made higher education possible for me, and

it changed the course of my life. More people should have this opportunity, in a

society that is suffering from falling economic and social mobility.

The 10K-B.A. is exactly the kind of innovation we would expect in an industry