|

History > 2012 > USA > Economy (II)

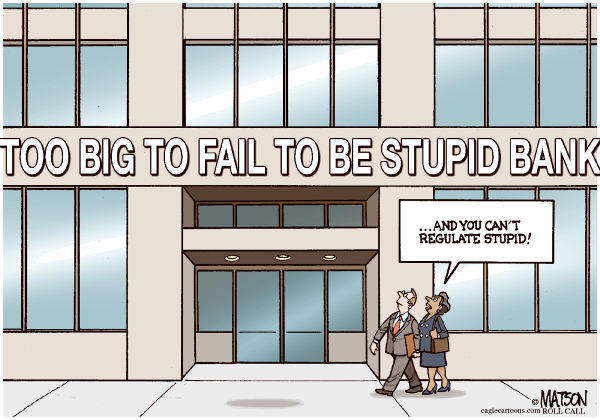

R.J. Matson

is the editorial cartoonist

at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and

Roll Call,

and is syndicated internationally by Cagle Cartoons.

Cagle

22 May 2012

U.S. Winds Down

Longer Benefits

for the Unemployed

May 28, 2012

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

Hundreds of thousands of out-of-work Americans are receiving

their final unemployment checks sooner than they expected, even though Congress

renewed extended benefits until the end of the year.

The checks are stopping for the people who have the most difficulty finding

work: the long-term unemployed. More than five million people have been out of

work for longer than half a year. Federal benefit extensions, which supplemented

state funds for payments up to 99 weeks, were intended to tide over the

unemployed until the job market improved.

In February, when the program was set to expire, Congress renewed it, but also

phased in a reduction of the number of weeks of extended aid and effectively

made it more difficult for states to qualify for the maximum aid. Since then,

the jobless in 23 states have lost up to five months’ worth of benefits.

Next month, an additional 70,000 people will lose benefits earlier than they

presumed, bringing the number of people cut off prematurely this year to close

to half a million, according to the National Employment Law Project. That

estimate does not include people who simply exhausted the weeks of benefits they

were entitled to.

Separate from the Congressional action, some states are making it harder to

qualify for the first few months of benefits, which are covered by taxes on

employers. Florida, where the jobless rate is 8.7 percent, has cut the number of

weeks it will pay and changed its application procedures, with more than half of

all applicants now being denied.

The federal extension of jobless benefits has been a contentious issue in

Washington. Republicans worry that it prolongs joblessness and say it has not

kept the unemployment rate down, while Democrats argue that those out of work

have few alternatives and that the checks are one of the most effective forms of

stimulus, since most of it is spent immediately.

After the most recent compromise reached in February, another renewal seems

unlikely.

The expiration of benefits is one factor contributing to what many economists

refer to as a “fiscal cliff,” or a drag on the economy at the end of this year

when tax cuts and recession-related spending measures will all come to an end

unless Congress acts. The Congressional Budget Office warned last week that the

combination could contribute to another recession next year.

Candace Falkner, 50, got her last unemployment check in mid-May, when extended

benefits were curtailed in eight states. Since then she has applied for food

stamps and begun a commission-only, door-to-door sales job. Since losing her job

two years ago, Ms. Falkner said, she has earned a master’s degree in psychology

and applied for work at numerous social service agencies as well as places like

Walmart, but no offers came.

Ms. Falkner, who lives on the outskirts of Chicago, said she was grateful for

the checks she received. But when they ended, she said, “They should have had

some program in place to funnel those people back into the job market. Not to

just leave them out there cold, saying, ‘The job market has improved, but

there’s still 60,000 people in the city who can’t find one.’ ”

Unemployment is lower than it was when the emergency unemployment extensions

were ramped up in November 2009. Now, it is 8.1 percent, down from 9.9 percent

then. But it is still far higher than pre-recession norms, and there are more

than three job seekers for every opening.

Proponents of extended benefits say the cuts are premature. Chad Stone, the

chief economist at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said

Congress had never before put the brakes on extended benefits when the labor

market was so weak. “It’s moving in the wrong direction, and it’s occurring at a

time when unemployment is very high,” he said.

Conservative economists and political leaders have argued that unemployment

benefits prolong joblessness and simply transfer wealth from one area of the

economy to another without contributing to growth.

Kevin A. Hassett, director of economic policy studies at the conservative

American Enterprise Institute, said, “I haven’t liked the 99-week solution from

the beginning because it creates an environment where people are subsidized to

become a structural unemployment problem.”

Still, he is troubled by the latest developments. “If you just reduce the weeks

of unemployment for people already unemployed but don’t do anything else, it’s a

bad deal,” he said, “because they’re already about the worst-off people in

society.”

He points to alternatives like using unemployment money to encourage

entrepreneurship or paying benefits in a lump sum, rather than over time, to

encourage people to find work faster.

Most states offer 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, plus the federal extensions

that kicked in after the financial crash.

The number of extra weeks available by state is determined by several factors,

including the state’s unemployment rate and whether it is higher than three

years earlier. So states like California have had benefits cut even though the

unemployment rate there is still almost 11 percent.

“Benefits have ended not because economic conditions have improved, but because

they have not significantly deteriorated in the past three years,” Hannah Shaw,

a researcher at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, wrote in a blog

post. In May, an estimated 95,000 people lost benefits in California.

After the recession, 99 weeks became a symbol of the plight of the jobless, with

those who exhausted their benefits calling themselves “99 weekers” or “99ers.”

But by the end of September, the extended benefits will end in the last three

states providing 99 weeks of assistance — Nevada, New Jersey and Rhode Island.

Some states have tightened eligibility as well. Nationwide, most people apply

for benefits by phone. Last August, Florida began requiring people to apply

online and to complete a 45-minute test to assess their job skills, according to

a complaint submitted to the federal labor secretary by the National Employment

Law Project and Florida Legal Services.

The complaint said that applicants with limited Internet access or English

skills, disabilities or difficulty reading had effectively been shut out, and

that failure to complete the assessment was illegally being used to deny

benefits. Denials have soared; now just over half of applicants are rejected.

Nationally, 30 percent of applicants are rejected, according to the law project.

The changes have saved the state $2.7 million, according to James Miller, a

spokesman for the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity. The state’s

unemployment rate, he pointed out, has declined for 10 straight months. “The

Department of Economic Opportunity provides accommodations to individuals with

barriers to filing their claims,” he wrote in an e-mail. “D.E.O. welcomes any

review and is certain that Florida’s statutory changes are in full compliance

with federal law.”

The Labor Department is reviewing Florida’s unemployment program in response to

multiple complaints, a spokesman said.

U.S. Winds Down Longer Benefits for the

Unemployed, NYT, 28.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/business/

economy/extended-federal-unemployment-benefits-begin-to-wind-down.html

In Western Washington,

Drivers See Gasoline Prices

Heading the Wrong Way

May 24, 2012

The New York Times

By KIRK JOHNSON

TACOMA, Wash. — A lot has come down the pike since the summer

of 2008, which for many Americans may already feel like the closed chapter of an

old book. But here on the West Coast there is an unhappy echo: gasoline prices.

One thin dime separates the current average price of a regular gallon of gas

from Tacoma’s historic high of $4.37 that was set in late June 2008. And while

most Americans have caught a break over the last year, with average prices

falling more than 4 percent per gallon compared with this time last year, in

Western Washington they were up almost 8 percent as of Wednesday, according to

the Oil Price Information Service, a petroleum-pricing research group.

A bottleneck in the archipelago of oil refineries that supply the region is the

short explanation; some are closed for maintenance, one here in Washington is

temporarily disabled after a fire. The resulting pincer — a still-tough economy

compounded by stinging transportation costs — has clipped wallets in places like

Tacoma, a working town south of Seattle still tied to the world of timber and

shipping.

A few hours chatting around the pumps at a local gas stop on Monday underscored

the pain.

“Things are a little, little bit better than they were,” said Dennis Barker, a

former construction worker who started a home-renovation business about a month

ago with a friend. “But I’m spending more — I’m going around trying to drum up

some business,” he said. The $50 a week he spends on gasoline imposes strict

efficiencies, Mr. Barker said, on everything else.

For people on fixed or reduced incomes, lingeringly high prices create a ripple

that changes patterns of life in many ways, large and small. David Moceri, who

was laid off this spring from a mattress factory, now buys no more than $10 of

gasoline at a time. Harvey Johnson, a self-employed handyman, used to carry his

handyman tools, like his ladder, in a pickup truck from job to job.

Now he stuffs it all in his Honda, the ladder jutting from the back-seat windows

like an afterthought.

“Half as much gas,” he said.

Roy Harris is a retired metal-plating worker and passionate cyclist — 100 miles

a week or more at age 72, and three times on the 200-mile Seattle-to-Portland

Classic. But he no longer drives to the trails he once loved with his bicycle in

the back of his truck, and instead just rides around his neighborhood.

“We’ve cut our driving down, probably in half,” said Mr. Harris, whose primary

income is the Social Security checks that he and his wife receive. “Gas has

really killed us.”

A spokesman for AAA Washington, Dave Overstreet, said that spring can often be

the cruelest season for gasoline on the West Coast, which is largely cut off

from the pipeline and refining system that spiders up from the Gulf of Mexico.

The Cascade Range here in the Pacific Northwest and the Sierra Nevada in

California mark a kind of boundary from the rest of the nation, he said, in

gasoline economics.

Refineries in California also routinely reduce production in the spring,

preparing for the summer fuel blends mandated by California regulators. And

supplies in Washington and Oregon have been further crimped by the shutdown of

Washington’s biggest refinery — Cherry Point, owned by the oil giant BP — after

a fire in February. A spokesman for BP said on Tuesday that the plant was

restarting, but would take some time to resume full production.

In any event, demand also usually goes up in late May, Memorial Day being the

unofficial launching pad of the vacation driving season, putting supply and

demand back in collision.

“Once they get up and running again, even with the demand being higher, I think

that we’ll certainly see things stabilize,” Mr. Overstreet said. How long before

prices actually go back down? “Anybody’s guess,” he said.

Some drivers here in Tacoma say they have just stopped counting the whirring

nickels and dimes. Others say they believe that the slowly improving economy,

still spotty in its gains, will pick up. The local unemployment rate in Tacoma

has actually risen in recent months, to 9.8 percent in March from 8.8 percent

last November, according to federal figures, even as the statewide rate and the

broader Seattle metro area jobless rates have continued to fall.

“You have to get gas either way,” said Robin Senirajjangkul, 23, who is studying

at a local community college and tending bar to make ends meet. “But I do love

my Yaris,” she said, patting her Toyota compact, which looked ready for the road

with its big fuzzy steering wheel. “Good gas mileage,” she said.

In Western Washington, Drivers See Gasoline

Prices Heading the Wrong Way, NYT, 24.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/25/us/in-western-washington-drivers-see-gasoline-prices-heading-the-wrong-way.html

How Change Happens

May 21, 2012

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

Forty years ago, corporate America was bloated, sluggish and

losing ground to competitors in Japan and beyond. But then something astonishing

happened. Financiers, private equity firms and bare-knuckled corporate

executives initiated a series of reforms and transformations.

The process was brutal and involved streamlining and layoffs. But, at the end of

it, American businesses emerged leaner, quicker and more efficient.

Now we are apparently going to have a presidential election about whether this

reform movement was a good thing. Last week, the Obama administration unveiled

an attack ad against Mitt Romney’s old private equity firm, Bain Capital,

portraying it as a vampire that sucks the blood from American companies. Then

Vice President Joseph Biden Jr. gave one of those cable-TV-type speeches,

lambasting Wall Street and saying we had to be a country that makes things

again.

The Obama attack ad accused Bain Capital of looting a steel company called GST

in the 1990s and then throwing its workers out on the street. The ad itself

barely survived a minute of scrutiny. As Kimberly Strassel noted in The Wall

Street Journal, the depiction is wildly misleading.

The company was in terminal decline before Bain entered the picture, seeing its

work force fall from 4,500 to less than 1,000. It faced closure when Romney and

Bain, for some reason, saw hope for it in 1993. Bain acquired it, induced banks

to loan it money and poured $100 million into modernization, according to

Strassel. Bain held onto the company for eight years, hardly the pattern of a

looter. Finally, after all the effort, the company, like many other old-line

steel companies, filed for bankruptcy protection in 2001, two years after Romney

had left Bain.

This is the story of a failed rescue, not vampire capitalism.

But the larger argument is about private equity itself, and about the changes

private equity firms and other financiers have instigated across society. Over

the past several decades, these firms have scoured America looking for

underperforming companies. Then they acquire them and try to force them to get

better.

As Reihan Salam noted in a fair-minded review of the literature in National

Review, in any industry there is an astonishing difference in the productivity

levels of leading companies and the lagging companies. Private equity firms like

Bain acquire bad companies and often replace management, compel executives to

own more stock in their own company and reform company operations.

Most of the time they succeed. Research from around the world clearly confirms

that companies that have been acquired by private equity firms are more

productive than comparable firms.

This process involves a great deal of churn and creative destruction. It does

not, on net, lead to fewer jobs. A giant study by economists from the University

of Chicago, Harvard, the University of Maryland and the Census Bureau found that

when private equity firms acquire a company, jobs are lost in old operations.

Jobs are created in new, promising operations. The overall effect on employment

is modest.

Nor is it true that private equity firms generally pile up companies with debt,

loot them and then send them to the graveyard. This does happen occasionally

(the tax code encourages debt), but banks would not be lending money to private

equity-owned companies, decade after decade, if those companies weren’t

generally prosperous and creditworthy.

Private equity firms are not lovable, but they forced a renaissance that revived

American capitalism. The large questions today are: Will the U.S. continue this

process of rigorous creative destruction? More immediately, will the nation take

the transformation of the private sector and extend it to the public sector?

While American companies operate in radically different ways than they did 40

years ago, the sheltered, government-dominated sectors of the economy —

especially education, health care and the welfare state — operate in

astonishingly similar ways.

The implicit argument of the Republican campaign is that Mitt Romney has the

experience to extend this transformation into government.

The Obama campaign seems to be drifting willy-nilly into the opposite camp,

arguing that the pressures brought to bear by the capital markets over the past

few decades were not a good thing, offering no comparably sized agenda to reform

the public sector.

In a country that desperately wants change, I have no idea why a party would not

compete to be the party of change and transformation. For a candidate like

Obama, who successfully ran an unconventional campaign that embodied and

promised change, I have no idea why he would want to run a campaign this time

that regurgitates the exact same ads and repeats the exact same arguments as so

many Democratic campaigns from the ancient past.

How Change Happens, NYT, 21.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/22/opinion/brooks-how-change-happens.html

More Men

Enter Fields Dominated by Women

May 20,

2012

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN and ROBERT GEBELOFF

HOUSTON —

Wearing brick-red scrubs and chatting in Spanish, Miguel Alquicira settled a

tiny girl into an adult-size dental chair and soothed her through a set of

X-rays. Then he ushered the dentist, a woman, into the room and stayed on to

serve as interpreter.

A male dental assistant, Mr. Alquicira is in the minority. But he is also part

of a distinctive, if little noticed, shift in workplace gender patterns. Over

the last decade, men have begun flocking to fields long the province of women.

Mr. Alquicira, 21, graduated from high school in a desolate job market, one in

which the traditional opportunities, like construction and manufacturing, for

young men without a college degree had dried up. After career counselors told

him that medical fields were growing, he borrowed money for an eight-month

training course. Since then, he has had no trouble finding jobs that pay $12 or

$13 an hour.

He gave little thought to the fact that more than 90 percent of dental

assistants and hygienists are women. But then, young men like Mr. Alquicira have

come of age in a world of inverted expectations, where women far outpace men in

earning degrees and tend to hold jobs that have turned out to be, by and large,

more stable, more difficult to outsource, and more likely to grow.

“The way I look at it,” Mr. Alquicira explained, without a hint of awareness

that he was turning the tables on a time-honored feminist creed, “is that

anything, basically, that a woman can do, a guy can do.”

After years of economic pain, Americans remain an optimistic lot, though they

define the American dream not in terms of mansions and luxury cars but as

something more basic — a home, a college degree, financial security and enough

left over for a few extras like dining out, according to a study by the Pew

Center on the States’ Economic Mobility Project. That financial security usually

requires a steady full-time job with benefits, something that has become harder

to find, particularly for men and for those without a college degree. While

women continue to make inroads into prestigious, high-wage professions dominated

by men, more men are reaching for the dream in female-dominated occupations that

their fathers might never have considered.

The trend began well before the crash, and appears to be driven by a variety of

factors, including financial concerns, quality-of-life issues and a gradual

erosion of gender stereotypes. An analysis of census data by The New York Times

shows that from 2000 to 2010, occupations that are more than 70 percent female

accounted for almost a third of all job growth for men, double the share of the

previous decade.

That does not mean that men are displacing women — those same occupations

accounted for almost two-thirds of women’s job growth. But in Texas, for

example, the number of men who are registered nurses nearly doubled in that time

period, rising from just over 9 percent of nurses to almost 12 percent. Men make

up 23 percent of Texas public schoolteachers, but almost 28 percent of

first-year teachers.

The shift includes low-wage jobs as well. Nationally, two-thirds more men were

bank tellers, almost twice as many were receptionists and two-thirds more were

waiting tables in 2010 than a decade earlier.

Even more striking is the type of men who are making the shift. From 1970 to

1990, according to a study by Mary Gatta, the senior scholar at Wider

Opportunities for Women, and Patricia A. Roos, a sociologist at Rutgers, men who

took so-called pink-collar jobs tended to be foreign-born non-English speakers

with low education levels — men who, in other words, had few choices.

Now, though, the trend has spread among men of nearly all races and ages, more

than a third of whom have a college degree. In fact, the shift is most

pronounced among young, white, college-educated men like Charles Reed, a

sixth-grade math teacher at Patrick Henry Middle School in Houston.

Mr. Reed, 25, intended to go to law school after a two-year stint with Teach for

America, but he fell in love with the job. Though he says the recession had

little to do with his career choice, he believes the tough times that have

limited the prospects for new law school graduates have also helped make his

father, a lawyer, more accepting.

Still, Mr. Reed said of his father, “In his mind, I’m just biding time until I

decide to jump into a better profession.”

To the extent that the shift to “women’s work” has been accelerated by

recession, the change may reverse when the economy recovers. “Are boys today

saying, ‘I want to grow up and be a nurse?’ ” asked Heather Boushey, senior

economist at the Center for American Progress. “Or are they saying, ‘I want a

job that’s stable and recession proof?’ ”

In interviews, however, about two dozen men played down the economic

considerations, saying that the stigma associated with choosing such jobs had

faded, and that the jobs were appealing not just because they offered stable

employment, but because they were more satisfying.

“I.T. is just killing viruses and clearing paper jams all day,” said Scott

Kearney, 43, who tried information technology and other fields before becoming a

nurse in the pediatric intensive care unit at Children’s Memorial Hermann

Hospital in Houston.

Daniel Wilden, a 26-year-old Army veteran and nursing student at the University

of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he had gained respect for

nursing when he saw a female medic use a Leatherman tool to save the life of his

comrade. “She was a beast,” he said admiringly.

More than a few men said their new jobs had turned out to be far harder than

they imagined.

But these men can expect success. Men earn more than women even in

female-dominated jobs. And white men in particular who enter those fields easily

move up to supervisory positions, a phenomenon known as the glass escalator — as

opposed to the glass ceiling that women encounter in male-dominated professions,

said Adia Harvey Wingfield, a sociologist at Georgia State University. More men

in an occupation can also raise wages for everyone, though as yet men’s share of

these jobs has not grown enough to have an overall effect on pay.

“Simply because higher-educated men are entering these jobs does not mean that

it will result in equality in our workplaces,” said Ms. Gatta of Wider

Opportunities for Women.

Still, economists have long tried to figure out how to encourage more

integration in the work force. Now, it seems to be happening of its own accord.

“I hated my job every single day of my life,” said John Cook, 55, who got a

modest inheritance that allowed him to leave the company where he earned

$150,000 a year as a database consultant and enter nursing school.

His starting salary will be about a third what he once earned, but database

consulting does not typically earn hugs like the one Mr. Cook recently received

from a girl after he took care of her premature baby sister. “It’s like, people

get paid for doing this kind of stuff?” Mr. Cook said, choking up as he

recounted the episode.

Several men cited the same reasons for seeking out pink-collar work that have

drawn women to such careers: less stress and more time at home. At John G.

Osborne Elementary, Adrian Ortiz, 42, joked that he was one of the few Mexicans

who made more in his native country, where he was a hard-working lawyer, than he

did in the United States as a kindergarten teacher in a bilingual classroom.

“Now,” he said, “my priorities are family, 100 percent.”

Betsey Stevenson, a labor economist at the Wharton School at the University of

Pennsylvania, said she was not surprised that changing gender roles at home,

where studies show men are shouldering more of the domestic burden and spending

more time parenting, are now showing up in career choices.

“We tend to study these patterns of what’s going on in the family and what’s

going on in the workplace as separate, but they’re very much intertwined,” she

said. “So as attitudes in the family change, attitudes toward the workplace have

changed.”

In a classroom at Houston Community College, Dexter Rodriguez, 35, said his job

in tech support had not been threatened by the tough economy. Nonetheless, he

said, his family downsized the house, traded the new cars for used ones and

began to live off savings, all so Mr. Rodriguez could train for a career he

regarded as more exciting.

“I put myself into the recession,” he said, “because I wanted to go to nursing

school.”

More Men Enter Fields Dominated by Women, NYT, 20.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/21/business/increasingly-men-seek-success-in-jobs-dominated-by-women.html

Facebook Gold Rush: Fanfare vs. Realities

May 19, 2012

The New York Times

By GRETCHEN MORGENSON

IT’S an old line on Wall Street: If you can get your hands on

a hot new stock, you probably don’t want it.

This bit of Street wisdom came to mind last week, as Facebook went public amid

so much fanfare.

The stock eked out a 23-cent gain on its Day 1, to $38.23. This suggests that

many professional money managers viewed all the hype as just that. Whatever the

long-term prospects of this company — an issue over which reasonable people

reasonably disagree — the idea that small-time investors might get rich fast

struck the pros as absurd.

It is true that initial public offerings have increasingly become a game for

early investors and their Wall Street enablers. Since the 1980s, average

first-day gains on new stock issues have risen steadily. According to one 2006

study, the average first-day return on I.P.O.’s in the 1980s was 7 percent. By

the mid-1990s, it was 15 percent. In the 1999-2000 dot-com boom, it was 65

percent.

We all know how that last one turned out.

It’s no coincidence that as those averages were rising, individual investors

were becoming more enamored with the stock market. The great democratization of

the equity market, which began in the 1980s, lured small investors into the

game.

A lot of these people got burned. Academics at the Warrington College of

Business Administration at the University of Florida recently compiled a list of

about 250 companies that doubled — at least — in price on their first trading

day. Many quickly fell back to earth.

Going back to 1975, the list provides some of the greatest hits in I.P.O. land.

The top 10 first-day gainers all went public in the Internet boom. They included

VA Linux, which rose almost 700 percent, to a market capitalization of more than

$1 billion, and The Globe.com, which produced a gain of 606 percent on its first

day as a public company. Foundry Networks and WebMethods soared more than 500

percent.

Some of the companies on the list have disappeared or have been acquired. Others

are still around, to lesser and greater degrees. TheGlobe.com trades at less

than a penny a share. VA Linux is now called Geeknet and, as of Friday, had a

market value of $94 million.

Why did Facebook get a relatively slow start out of the trading gate? One

possibility is that the investment bankers who priced the stock considered the

history of private trading in the shares before the offering. Facebook was

unusual in this way, Laszlo Birinyi of Birinyi Associates pointed out last week.

“There was trading before the I.P.O., so many investors have some feel, some

idea of pricing,” he noted. Most offerings are priced based upon what the

company and its bankers guess the stock will fetch.

Indications are that Facebook was bought primarily by individual investors, not

institutions. Indeed, institutions that had invested early were big sellers in

the I.P.O. To many market veterans, this showed that the smart money was getting

out while the getting was good.

With investors still believing the advice of Peter Lynch, the former Fidelity

fund manager who told individuals to buy stocks of companies they knew as

consumers, it is easy to see why Facebook’s offering resonated with the public.

But now comes the hard part: operating as a company that returns its investors’

favors with actual earnings.

Facebook Gold Rush: Fanfare vs. Realities,

NYT, 19.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/20/business/in-facebook-stock-rush-fanfare-vs-realities.html

End of the Affair?

May 14, 2012

The New York Times

Investors are shunning the stock market, and who can blame

them? As serial bubbles have burst, faith in the market has been rewarded with

shattered retirements. At the same time, trust has been destroyed by scandals

and — as demonstrated by the reckless trading at JPMorgan Chase — the slow,

uncertain pace of financial reform.

There has been less buying and selling of stock, and there have been huge

outflows of investor dollars from domestic stock mutual funds, as detailed

recently by The Times’s Nathaniel Popper. If the trend continues, the result

could be a less robust market, with fewer companies opting to raise money by

issuing shares and fewer investors willing to put their retirement savings into

stocks.

Policy makers should pay attention. Evidence suggests that investors are not

merely reacting to tough conditions, but rather are staying away because they do

not trust the market. Restoring trust is crucial to restoring the market.

American stocks have doubled in price since the market hit bottom three years

ago. But trading in the United States stock market has not only failed to

recover since the 2008 financial crash, it has continued to fall. In April,

average daily trades stood at 6.5 billion, about half their peak four years ago.

By comparison, after the market busts of 1987 and 2001, trading recovered within

two years. In fact, going back to 1960, trading had never declined for three

consecutive years, let alone four and counting.

Investors haven’t just hunkered down, they have headed for the exits. Since the

start of 2008, domestic stock mutual funds, a common way for individuals to

invest, were drained of more than $400 billion, compared with an inflow of $52

billion in the four years before that.

These investors have increasingly opted for bonds over stocks, with reason. From

the peak of the dot-com era in March 2000, stocks have risen about 10 percent, a

paltry gain once fees, taxes and risks are factored in. Stocks are still down

about 5 percent from the peak in October 2007, even with prices doubling since

mid-2009.

There is also the feeling that the market has become increasingly unfair to

investors. For example, Mr. Popper also reported recently on rebates to brokers

from stock exchanges. In general, brokers are required to find the best prices

for clients who pay them to buy and sell shares. But with the nation’s 13

exchanges now paying brokers for sending them business, brokers may have an

incentive to search for the biggest rebate rather than the best price. A new

study has estimated that rebates could be costing mutual funds, pension funds

and individual investors as much as $5 billion a year.

Also known as “maker-taker” pricing, the rebates have caught the attention of

market researchers and investor advocates, including two former economists for

the Securities and Exchange Commission who issued a report in 2010 saying that

“in other contexts, these payments would be recognized as illegal kickbacks.”

So add rebates to to the S.E.C.’s long list of market issues to be investigated.

In the meantime, they are a reminder that brokers often do not have an

obligation to act in a client’s best interest — and that efforts to change the

law to put a client’s interest first have been repeatedly defeated in the face

of industry pressure.

End of the Affair?, NYT, 14.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/15/opinion/end-of-the-affair.html

JPMorgan Loss Claims Official Who Oversaw Trading Unit

May 13, 2012

The New York Times

By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ and JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERG

Stung by a huge trading loss, JPMorgan Chase will replace

three top traders starting Monday, including one of the top women on Wall

Street, in an effort to stem the ire that the bank faces from regulators and

investors.

They are the first departures of leading officials since Jamie Dimon, the chief

executive, disclosed the bank’s stunning $2 billion loss on Thursday.

The huge scope of the complex credit bet caught senior bank officials off-guard

when it began to sour last month and has set off renewed regulatory scrutiny of

the industry. Mr. Dimon has largely sidestepped blame for the loss, although he

has offered numerous apologies for the blunder, the biggest of his eight-year

tenure at JPMorgan, the nation’s largest bank.

Ina Drew, a 55-year-old banker who has worked at the company for three decades

and is the chief investment officer, has offered to resign and will step aside

Monday, said several bank executives who would not speak publicly because the

resignations had not been completed.

Her exit would be a precipitous fall for a trusted lieutenant of Mr. Dimon. Last

year, Ms. Drew earned roughly $14 million, making her the bank’s

fourth-highest-paid officer. From her desk in Manhattan, she oversaw the London

office that assembled the trade, a growing unit that oversees a portfolio of

nearly $400 billion. Two traders who worked for Ms. Drew are also likely to

leave shortly. Ms. Drew was not available for comment.

Mr. Dimon, who will face shareholders at the company’s annual meeting Tuesday,

has been on a public campaign of contrition in recent days. Mr. Dimon, the

famously confident, even cocky, executive, repeated his apologies in a broadcast

Sunday of NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

“We made a terrible, egregious mistake and there’s almost no excuse for it,” Mr.

Dimon said, adding that the bank was “sloppy” and “stupid.” He also acknowledged

that the timing of the loss was a gift for advocates of more stringent

regulation.

Ms. Drew had tearfully offered to resign multiple times since the scale of the

loss became apparent in late April, but Mr. Dimon had held off until now on

accepting it, said people familiar with the situation.

A skilled trader who once said she relished a crisis, Ms. Drew — and the

disastrous trade — had become a liability for the firm, whose announcement of

the trading loss caused JPMorgan’s shares to plunge 9.3 percent on Friday. It

was unclear what type of severance package Ms. Drew will receive.

“It’s not surprising that officials there are taking the fall, but this is one

of the fastest movements I have seen,” said Michael Mayo, an analyst with Credit

Agricole Securities in New York. “Mr. Dimon gets an A for moving to stem the

wrath of regulators, but an F for not finding the problem in the first place.”

With the furor intensifying, former JPMorgan executives said, Ms. Drew was

clearly feeling pressure to step down, especially with regulators and members of

Congress pointing to the loss as an example of why tighter oversight of the

nation’s biggest financial institutions is needed.

“The bank has taken bigger losses in investment banking and elsewhere, but

because of the timing, she is being piled upon as this huge failure,” said a

former senior executive, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the

delicate nature of the situation.

Executives said that within the last several months, Ms. Drew told traders at

the bank’s chief investment office to execute trades meant to shield the bank

from the turmoil in Europe. Ms. Drew thought those bets could protect the bank

from losses and even earn a tidy profit, these employees said.

But when market tides abruptly shifted in April and early May, Ms. Drew’s

instructions to traders to trim what had become a gigantic bet came too late to

avoid racking up losses that could eventually exceed the current $2 billion

estimate. Within the bank, there is also ample frustration that instead of

reducing the losses, Ms. Drew’s traders may have worsened them.

Besides Ms. Drew, Achilles Macris, a top JPMorgan official in London, is

expected to depart, as is a senior London trader, Javier Martin-Artajo. Under

Mr. Dimon’s leadership, the chief investment office has grown substantially in

recent years, which until recently was little noticed by analysts and investors.

Some former colleagues said Ms. Drew pushed hard for the bank to take calculated

risks. She was never a “schmoozer” and kept a very low profile, bank executives

said, at both JPMorgan and Chemical Bank, one of JPMorgan’s predecessor

companies, which she joined in 1982. But Ms. Drew was not shy with her opinions.

She routinely told senior executives in the firm’s trading businesses if she did

not agree with their positions, one of the former colleagues said.

Also under scrutiny is another of Ms. Drew’s subordinates, Bruno Iksil, the

trader in London who gained notoriety last month for his role in the losses. He

was nicknamed the London whale, because the positions he took were so large that

they distorted credit prices. Other departures in London are likely.

Former senior-level executives at JPMorgan said the loss was the first real

misstep that Ms. Drew had experienced, having successfully navigated the

financial crisis. They added that the recent trades were not meant to drum up

bigger profits for the bank, but to offset risk.

“This is killing her,” one of the former JPMorgan executives said, adding that

“in banking, there are very large knives.”

In February, Ms. Drew traveled to Washington with other JPMorgan executives,

including Barry Zubrow, who oversees regulatory affairs, to explain why

strategies like the one that later soured could offset risk within the bank. It

was Ms. Drew’s first such trip to Washington, and she was called upon as an

expert to discuss how to manage the gap between assets and liabilities for big

banks, specifically how to handle the capital risks posed by having more in

deposits than in loans.

“She’s a person of the highest integrity,” said Walter Shipley, the former chief

executive of Chase Manhattan and before that, Chemical Bank. “She was

conservative on the risk side, she’s not a speculator.” Mr. Shipley retired from

Chase in 2000, just before its merger with J.P. Morgan, but has kept in touch

with Ms. Drew.

Mr. Shipley had lunch with her two months ago, he said, adding that Ms. Drew,

her husband, and two children live in Short Hills, N.J., not far from his home

in Summit.

Despite Ms. Drew’s low profile beyond JPMorgan Chase — many top Wall Street

figures said Sunday that they had never heard of her until the news of the

trading loss — she was a passionate advocate for women within the firm. In the

largely male word of the banking elite, trading is an especially

testosterone-laden niche, but Ms. Drew encouraged women to go into trading,

arguing that working predictable market hours was actually a benefit in terms of

balancing career and family.

“I’m very upset for her,” said William Harrison, who was chief executive of

JPMorgan Chase before Mr. Dimon’s tenure. “She looked out for the company first.

I’ve always been a great fan.”

Michael J. de la Merced and Ben Protess contributed reporting.

JPMorgan Loss Claims Official Who Oversaw

Trading Unit, NYT, 13.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/14/business/jpmorgan-chase-executive-to-resign-in-trading-debacle.html

U.S. Added Only 115,000 Jobs in April; Rate Is 8.1%

May 4, 2012

The New York Times

By CATHERINE RAMPELL

The United States had another month of disappointing job

growth in April, the latest government report showed Friday.

The nation’s employers added 115,000 positions on net, after adding 154,000 in

March, according to the Labor Department. April’s job growth was less than what

economists had been predicting. The unemployment rate ticked down to 8.1 percent

in April, from 8.2 percent, but that was because workers dropped out of the

labor force.

The share of working-age Americans who are in the labor force, either by working

or actively looking for a job, is now at its lowest level since 1981 — when far

fewer women were doing paid work.

“It’s a pretty sluggish report over all,” said Andrew Tilton, a senior economist

at Goldman Sachs, noting that economists had expected more younger workers to

join the labor force as the economy improved. “There were a lot of younger

people who had gone back to school to get more education and training, and we

thought we’d see more of them joining the work force now. May, June and July —

the months when people are typically coming out of schooling — will be the big

test.”

The report contained other discouraging news; the average workweek, for example,

remained unchanged at 34.5 hours.

Government job losses, which totaled 15,000 in April, continued to weigh on the

economy, tugging down job growth as state and local governments grapple with

strained budgets. Private companies added 130,000 jobs, with professional and

business services, retail trade, and health care doing the most hiring.

Such job growth is not nearly fast enough to recover the losses from the Great

Recession and its aftermath. Today the United States economy is producing even

more goods and services than it did when the recession officially began in

December 2007, but with about five million fewer workers.

Given the many productivity gains across the economy — that is, the fact that

employers have learned how to make more with fewer workers — there is also

debate about what exactly “healthy” employment would look like in the current

economy, and whether it still makes sense to use the pre-financial-crisis

economy as a benchmark for what the employment landscape should look like.

On Thursday, John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San

Francisco, suggested that the “natural” rate of unemployment might now be as

high as 6.5 percent. Before the recession, economists generally believed it was

around 5 percent.

Productivity fell last quarter, though, which could spell good news for the

nearly 14 million idle workers sitting on the sidelines, if not necessarily for

the employers trying to squeeze more profits out of their existing work forces.

In one bright spot in Friday’s report, job growth figures for March and February

were revised upward, by a total of 53,000.

Economists are once again cautiously optimistic about what the next few months

may bring for the nation’s unemployed.

Job growth had picked up earlier this year, just as it had at the start at the

beginning of 2010 and 2011. In both of those years severe shocks to the global

economy — including the Arab Spring and Japanese tsunami last year — braked some

of that momentum. Economists are concerned that over the coming months rising

gasoline prices and slowing growth in places like China may similarly weigh on

demand for products and services from American businesses, and on hiring by

those businesses as well.

U.S. Added Only 115,000 Jobs in April; Rate

Is 8.1%, NYT, 4.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/05/business/economy/us-added-only-115000-jobs-in-april-rate-is-8-1.html

How to Get Business to Pay Its Share

May 3, 2012

The New York Times

By ALEX MARSHALL

JAMES MADISON never played with an iPhone, but he might have

had something to say about the news last weekend about Apple. Over the last few

years, the company has avoided paying billions of dollars in state and federal

taxes by routing profits through subsidiaries based in tax havens from Reno,

Nev., to the Caribbean.

This is a common practice among major American businesses, and back in 1787,

Madison saw it coming. Someday, he warned, companies could grow so large they

“would pass beyond the authority of a single state, and would do business in

other states.” To make sure the companies remained accountable to government, he

said the federal government should “grant charters of incorporation in cases

where the public good may require them, and the authority of a single state may

be incompetent.”

In other words, a National Companies Act.

Such an act would create a common corporate architecture for all American

companies doing business across state lines and internationally. It would

establish not only uniform tax policies but also national standards for the

structure of corporate boards, the power of chief executives, the relations of

management with workers and shareholders and the interaction of American

companies with other nations. National companies would have to abide by national

rules, and the option of shopping around for the most favorable laws or tax

policies simply wouldn’t exist.

It’s an idea that has been proposed and pursued many times, particularly during

the early 1900s, when companies like Standard Oil, which was a collection of

companies incorporated in various states and assembled into a national “trust,”

were becoming increasingly powerful. Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft,

Woodrow Wilson and, later, Franklin D. Roosevelt all supported the creation of a

national companies law, but the measures were consistently opposed by the

business community and eventually defeated.

Today, however, considering how much effort and money American companies expend

on keeping a competitive advantage by figuring out which loopholes to exploit

from the bewildering array of rules now in effect, they might not entirely

oppose reform. In an era of global competition, it could help to have a clear

set of standards. It’s certainly what other nations have. In Germany, for

example, national legislation established rules for the structure of corporate

boards. Britain’s Parliament establishes how a corporation can be created and

what its rights and responsibilities are.

Legally, there is little doubt that the United States Congress could impose

similar rules under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. Although the states

have traditionally been the main arena for corporate rules, the federal

government has long created national corporations, from the First Bank of the

United States in 1791 to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in 1967.

Congress could use this same power to require that companies doing business

across state lines have national corporate charters, which would subject them to

federal rules. Alternatively, it could simply set rules for corporate

organization and conduct that would apply to all interstate companies of a

certain size.

Passing a National Companies Act won’t be easy. Companies would hire lobbyists

to push for favorable rules. And some states with particularly easy

incorporation terms, like Delaware, might resist. Around 60 percent of Fortune

500 companies are incorporated in Delaware, and the state earns a great deal in

fees and tax revenues as a result.

But the Apple controversy shows that the nation is ready for reform. While the

company is a symbol of private enterprise, its existence is made possible by a

charter that some government writes and grants. It should serve public as well

as private ends — and pay its rightful share in taxes — or it should not exist

at all.

Alex Marshall is a senior fellow at the Regional Plan

Association,

an urban research and advocacy group,

and the author of the forthcoming book “The Surprising Design of

Market Economies.”

How to Get Business to Pay Its Share, NYT,

3.5.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/04/opinion/solving-the-corporate-tax-code-puzzle.html

How Apple Sidesteps Billions in Taxes

April 28, 2012

The New York Times

By CHARLES DUHIGG and DAVID KOCIENIEWSKI

RENO, Nev. — Apple, the world’s most profitable technology

company, doesn’t design iPhones here. It doesn’t run AppleCare customer service

from this city. And it doesn’t manufacture MacBooks or iPads anywhere nearby.

Yet, with a handful of employees in a small office here in Reno, Apple has done

something central to its corporate strategy: it has avoided millions of dollars

in taxes in California and 20 other states.

Apple’s headquarters are in Cupertino, Calif. By putting an office in Reno, just

200 miles away, to collect and invest the company’s profits, Apple sidesteps

state income taxes on some of those gains.

California’s corporate tax rate is 8.84 percent. Nevada’s? Zero.

Setting up an office in Reno is just one of many legal methods Apple uses to

reduce its worldwide tax bill by billions of dollars each year. As it has in

Nevada, Apple has created subsidiaries in low-tax places like Ireland, the

Netherlands, Luxembourg and the British Virgin Islands — some little more than a

letterbox or an anonymous office — that help cut the taxes it pays around the

world.

Almost every major corporation tries to minimize its taxes, of course. For

Apple, the savings are especially alluring because the company’s profits are so

high. Wall Street analysts predict Apple could earn up to $45.6 billion in its

current fiscal year — which would be a record for any American business.

Apple serves as a window on how technology giants have taken advantage of tax

codes written for an industrial age and ill suited to today’s digital economy.

Some profits at companies like Apple, Google, Amazon, Hewlett-Packard and

Microsoft derive not from physical goods but from royalties on intellectual

property, like the patents on software that makes devices work. Other times, the

products themselves are digital, like downloaded songs. It is much easier for

businesses with royalties and digital products to move profits to low-tax

countries than it is, say, for grocery stores or automakers. A downloaded

application, unlike a car, can be sold from anywhere.

The growing digital economy presents a conundrum for lawmakers overseeing

corporate taxation: although technology is now one of the nation’s largest and

most valued industries, many tech companies are among the least taxed, according

to government and corporate data. Over the last two years, the 71 technology

companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index — including Apple, Google,

Yahoo and Dell — reported paying worldwide cash taxes at a rate that, on

average, was a third less than other S.& P. companies’. (Cash taxes may include

payments for multiple years.)

Even among tech companies, Apple’s rates are low. And while the company has

remade industries, ignited economic growth and delighted customers, it has also

devised corporate strategies that take advantage of gaps in the tax code,

according to former executives who helped create those strategies.

Apple, for instance, was among the first tech companies to designate overseas

salespeople in high-tax countries in a manner that allowed them to sell on

behalf of low-tax subsidiaries on other continents, sidestepping income taxes,

according to former executives. Apple was a pioneer of an accounting technique

known as the “Double Irish With a Dutch Sandwich,” which reduces taxes by

routing profits through Irish subsidiaries and the Netherlands and then to the

Caribbean. Today, that tactic is used by hundreds of other corporations — some

of which directly imitated Apple’s methods, say accountants at those companies.

Without such tactics, Apple’s federal tax bill in the United States most likely

would have been $2.4 billion higher last year, according to a recent study by a

former Treasury Department economist, Martin A. Sullivan. As it stands, the

company paid cash taxes of $3.3 billion around the world on its reported profits

of $34.2 billion last year, a tax rate of 9.8 percent. (Apple does not disclose

what portion of those payments was in the United States, or what portion is

assigned to previous or future years.)

By comparison, Wal-Mart last year paid worldwide cash taxes of $5.9 billion on

its booked profits of $24.4 billion, a tax rate of 24 percent, which is about

average for non-tech companies.

Apple’s domestic tax bill has piqued particular curiosity among corporate tax

experts because although the company is based in the United States, its profits

— on paper, at least — are largely foreign. While Apple contracts out much of

the manufacturing and assembly of its products to other companies overseas, the

majority of Apple’s executives, product designers, marketers, employees,

research and development, and retail stores are in the United States. Tax

experts say it is therefore reasonable to expect that most of Apple’s profits

would be American as well. The nation’s tax code is based on the concept that a

company “earns” income where value is created, rather than where products are

sold.

However, Apple’s accountants have found legal ways to allocate about 70 percent

of its profits overseas, where tax rates are often much lower, according to

corporate filings.

Neither the government nor corporations make tax returns public, and a company’s

taxable income often differs from the profits disclosed in annual reports.

Companies report their cash outlays for income taxes in their annual Form 10-K,

but it is impossible from those numbers to determine precisely how much, in

total, corporations pay to governments. In Apple’s last annual disclosure, the

company listed its worldwide taxes — which includes cash taxes paid as well as

deferred taxes and other charges — at $8.3 billion, an effective tax rate of

almost a quarter of profits.

However, tax analysts and scholars said that figure most likely overstated how

much the company would hand to governments because it included sums that might

never be paid. “The information on 10-Ks is fiction for most companies,” said

Kimberly Clausing, an economist at Reed College who specializes in multinational

taxation. “But for tech companies it goes from fiction to farcical.”

Apple, in a statement, said it “has conducted all of its business with the

highest of ethical standards, complying with applicable laws and accounting

rules.” It added, “We are incredibly proud of all of Apple’s contributions.”

Apple “pays an enormous amount of taxes, which help our local, state and federal

governments,” the statement also said. “In the first half of fiscal year 2012,

our U.S. operations have generated almost $5 billion in federal and state income

taxes, including income taxes withheld on employee stock gains, making us among

the top payers of U.S. income tax.”

The statement did not specify how it arrived at $5 billion, nor did it address

the issue of deferred taxes, which the company may pay in future years or decide

to defer indefinitely. The $5 billion figure appears to include taxes ultimately

owed by Apple employees.

The sums paid by Apple and other tech corporations is a point of contention in

the company’s backyard.

A mile and a half from Apple’s Cupertino headquarters is De Anza College, a

community college that Steve Wozniak, one of Apple’s founders, attended from

1969 to 1974. Because of California’s state budget crisis, De Anza has cut more

than a thousand courses and 8 percent of its faculty since 2008.

Now, De Anza faces a budget gap so large that it is confronting a “death

spiral,” the school’s president, Brian Murphy, wrote to the faculty in January.

Apple, of course, is not responsible for the state’s financial shortfall, which

has numerous causes. But the company’s tax policies are seen by officials like

Mr. Murphy as symptomatic of why the crisis exists.

“I just don’t understand it,” he said in an interview. “I’ll bet every person at

Apple has a connection to De Anza. Their kids swim in our pool. Their cousins

take classes here. They drive past it every day, for Pete’s sake.

“But then they do everything they can to pay as few taxes as possible.”

Escaping State Taxes

In 2006, as Apple’s bank accounts and stock price were rising, company

executives came here to Reno and established a subsidiary named Braeburn Capital

to manage and invest the company’s cash. Braeburn is a variety of apple that is

simultaneously sweet and tart.

Today, Braeburn’s offices are down a narrow hallway inside a bland building that

sits across from an abandoned restaurant. Inside, there are posters of

candy-colored iPods and a large Apple insignia, as well as a handful of desks

and computer terminals.

When someone in the United States buys an iPhone, iPad or other Apple product, a

portion of the profits from that sale is often deposited into accounts

controlled by Braeburn, and then invested in stocks, bonds or other financial

instruments, say company executives. Then, when those investments turn a profit,

some of it is shielded from tax authorities in California by virtue of

Braeburn’s Nevada address.

Since founding Braeburn, Apple has earned more than $2.5 billion in interest and

dividend income on its cash reserves and investments around the globe. If

Braeburn were located in Cupertino, where Apple’s top executives work, a portion

of the domestic income would be taxed at California’s 8.84 percent corporate

income tax rate.

But in Nevada there is no state corporate income tax and no capital gains tax.

What’s more, Braeburn allows Apple to lower its taxes in other states —

including Florida, New Jersey and New Mexico — because many of those

jurisdictions use formulas that reduce what is owed when a company’s financial

management occurs elsewhere. Apple does not disclose what portion of cash taxes

is paid to states, but the company reported that it owed $762 million in state

income taxes nationwide last year. That effective state tax rate is higher than

the rate of many other tech companies, but as Ms. Clausing and other tax

analysts have noted, such figures are often not reliable guides to what is

actually paid.

Dozens of other companies, including Cisco, Harley-Davidson and Microsoft, have

also set up Nevada subsidiaries that bypass taxes in other states. Hundreds of

other corporations reap similar savings by locating offices in Delaware.

But some in California are unhappy that Apple and other California-based

companies have moved financial operations to tax-free states — particularly

since lawmakers have offered them tax breaks to keep them in the state.

In 1996, 1999 and 2000, for instance, the California Legislature increased the

state’s research and development tax credit, permitting hundreds of companies,

including Apple, to avoid billions in state taxes, according to legislative

analysts. Apple has reported tax savings of $412 million from research and

development credits of all sorts since 1996.

Then, in 2009, after an intense lobbying campaign led by Apple, Cisco, Oracle,

Intel and other companies, the California Legislature reduced taxes for

corporations based in California but operating in other states or nations.

Legislative analysts say the change will eventually cost the state government

about $1.5 billion a year.

Such lost revenue is one reason California now faces a budget crisis, with a

shortfall of more than $9.2 billion in the coming fiscal year alone. The state

has cut some health care programs, significantly raised tuition at state

universities, cut services to the disabled and proposed a $4.8 billion reduction

in spending on kindergarten and other grades.

Apple declined to comment on its Nevada operations. Privately, some executives

said it was unfair to criticize the company for reducing its tax bill when

thousands of other companies acted similarly. If Apple volunteered to pay more

in taxes, it would put itself at a competitive disadvantage, they argued, and do

a disservice to its shareholders.

Indeed, Apple’s decisions have yielded benefits. After announcing one of the

best quarters in its history last week, the company said it had net profits of

$24.7 billion on revenues of $85.5 billion in the first half of the fiscal year,

and more than $110 billion in the bank, according to company filings.

A Global Tax Strategy

Every second of every hour, millions of times each day, in living rooms and at

cash registers, consumers click the “Buy” button on iTunes or hand over payment

for an Apple product.

And with that, an international financial engine kicks into gear, moving money

across continents in the blink of an eye. While Apple’s Reno office helps the

company avoid state taxes, its international subsidiaries — particularly the

company’s assignment of sales and patent royalties to other nations — help

reduce taxes owed to the American and other governments.

For instance, one of Apple’s subsidiaries in Luxembourg, named iTunes S.à r.l.,

has just a few dozen employees, according to corporate documents filed in that

nation and a current executive. The only indication of the subsidiary’s presence

outside is a letterbox with a lopsided slip of paper reading “ITUNES SARL.”

Luxembourg has just half a million residents. But when customers across Europe,

Africa or the Middle East — and potentially elsewhere — download a song,

television show or app, the sale is recorded in this small country, according to

current and former executives. In 2011, iTunes S.à r.l.’s revenue exceeded $1

billion, according to an Apple executive, representing roughly 20 percent of

iTunes’s worldwide sales.

The advantages of Luxembourg are simple, say Apple executives. The country has

promised to tax the payments collected by Apple and numerous other tech

corporations at low rates if they route transactions through Luxembourg. Taxes

that would have otherwise gone to the governments of Britain, France, the United

States and dozens of other nations go to Luxembourg instead, at discounted

rates.

“We set up in Luxembourg because of the favorable taxes,” said Robert Hatta, who

helped oversee Apple’s iTunes retail marketing and sales for European markets

until 2007. “Downloads are different from tractors or steel because there’s

nothing you can touch, so it doesn’t matter if your computer is in France or

England. If you’re buying from Luxembourg, it’s a relationship with Luxembourg.”

An Apple spokesman declined to comment on the Luxembourg operations.

Downloadable goods illustrate how modern tax systems have become increasingly

ill equipped for an economy dominated by electronic commerce. Apple, say former

executives, has been particularly talented at identifying legal tax loopholes

and hiring accountants who, as much as iPhone designers, are known for their

innovation. In the 1980s, for instance, Apple was among the first major

corporations to designate overseas distributors as “commissionaires,” rather

than retailers, said Michael Rashkin, Apple’s first director of tax policy, who

helped set up the system before leaving in 1999.

To customers the designation was virtually unnoticeable. But because

commissionaires never technically take possession of inventory — which would

require them to recognize taxes — the structure allowed a salesman in high-tax

Germany, for example, to sell computers on behalf of a subsidiary in low-tax

Singapore. Hence, most of those profits would be taxed at Singaporean, rather

than German, rates.

The Double Irish

In the late 1980s, Apple was among the pioneers in creating a tax structure —

known as the Double Irish — that allowed the company to move profits into tax

havens around the world, said Tim Jenkins, who helped set up the system as an

Apple European finance manager until 1994.

Apple created two Irish subsidiaries — today named Apple Operations

International and Apple Sales International — and built a glass-encased factory

amid the green fields of Cork. The Irish government offered Apple tax breaks in

exchange for jobs, according to former executives with knowledge of the

relationship.

But the bigger advantage was that the arrangement allowed Apple to send

royalties on patents developed in California to Ireland. The transfer was

internal, and simply moved funds from one part of the company to a subsidiary

overseas. But as a result, some profits were taxed at the Irish rate of

approximately 12.5 percent, rather than at the American statutory rate of 35

percent. In 2004, Ireland, a nation of less than 5 million, was home to more

than one-third of Apple’s worldwide revenues, according to company filings.

(Apple has not released more recent estimates.)

Moreover, the second Irish subsidiary — the “Double” — allowed other profits to

flow to tax-free companies in the Caribbean. Apple has assigned partial

ownership of its Irish subsidiaries to Baldwin Holdings Unlimited in the British

Virgin Islands, a tax haven, according to documents filed there and in Ireland.

Baldwin Holdings has no listed offices or telephone number, and its only listed

director is Peter Oppenheimer, Apple’s chief financial officer, who lives and

works in Cupertino. Baldwin apples are known for their hardiness while

traveling.

Finally, because of Ireland’s treaties with European nations, some of Apple’s

profits could travel virtually tax-free through the Netherlands — the Dutch

Sandwich — which made them essentially invisible to outside observers and tax

authorities.

Robert Promm, Apple’s controller in the mid-1990s, called the strategy “the

worst-kept secret in Europe.”

It is unclear precisely how Apple’s overseas finances now function. In 2006, the

company reorganized its Irish divisions as unlimited corporations, which have

few requirements to disclose financial information.

However, tax experts say that strategies like the Double Irish help explain how

Apple has managed to keep its international taxes to 3.2 percent of foreign

profits last year, to 2.2 percent in 2010, and in the single digits for the last

half-decade, according to the company’s corporate filings.

Apple declined to comment on its operations in Ireland, the Netherlands and the

British Virgin Islands.

Apple reported in its last annual disclosures that $24 billion — or 70 percent —

of its total $34.2 billion in pretax profits were earned abroad, and 30 percent

were earned in the United States. But Mr. Sullivan, the former Treasury

Department economist who today writes for the trade publication Tax Analysts,

said that “given that all of the marketing and products are designed here, and

the patents were created in California, that number should probably be at least

50 percent.”

If profits were evenly divided between the United States and foreign countries,

Apple’s federal tax bill would have increased by about $2.4 billion last year,

he said, because a larger amount of its profits would have been subject to the

United States’ higher corporate income tax rate.

“Apple, like many other multinationals, is using perfectly legal methods to keep

a significant portion of their profits out of the hands of the I.R.S.,” Mr.

Sullivan said. “And when America’s most profitable companies pay less, the

general public has to pay more.”

Other tax experts, like Edward D. Kleinbard, former chief of staff of the

Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, have reached similar conclusions.

“This tax avoidance strategy used by Apple and other multinationals doesn’t just

minimize the companies’ U.S. taxes,” said Mr. Kleinbard, now a professor of tax

law at the University of Southern California. “It’s German tax and French tax

and tax in the U.K. and elsewhere.”

One downside for companies using such strategies is that when money is sent

overseas, it cannot be returned to the United States without incurring a new tax

bill.

However, that might change. Apple, which holds $74 billion offshore, last year

aligned itself with more than four dozen companies and organizations urging

Congress for a “repatriation holiday” that would permit American businesses to

bring money home without owing large taxes. The coalition, which includes

Google, Microsoft and Pfizer, has hired dozens of lobbyists to push for the

measure, which has not yet come up for vote. The tax break would cost the

federal government $79 billion over the next decade, according to a

Congressional report.

Fallout in California

In one of his last public appearances before his death, Steven P. Jobs, Apple’s

chief executive, addressed Cupertino’s City Council last June, seeking approval

to build a new headquarters.

Most of the Council was effusive in its praise of the proposal. But one

councilwoman, Kris Wang, had questions.

How will residents benefit? she asked. Perhaps Apple could provide free wireless

Internet to Cupertino, she suggested, something Google had done in neighboring

Mountain View.

“See, I’m a simpleton; I’ve always had this view that we pay taxes, and the city

should do those things,” Mr. Jobs replied, according to a video of the meeting.

“That’s why we pay taxes. Now, if we can get out of paying taxes, I’ll be glad

to put up Wi-Fi.”

He suggested that, if the City Council were unhappy, perhaps Apple could move.

The company is Cupertino’s largest taxpayer, with more than $8 million in

property taxes assessed by local officials last year.

Ms. Wang dropped her suggestion.

Cupertino, Ms. Wang said in an interview, has real financial problems. “We’re

proud to have Apple here,” said Ms. Wang, who has since left the Council. “But

how do you get them to feel more connected?”

Other residents argue that Apple does enough as Cupertino’s largest employer and

that tech companies, in general, have buoyed California’s economy. Apple’s

workers eat in local restaurants, serve on local boards and donate to local

causes. Silicon Valley’s many millionaires pay personal state income taxes. In

its statement, Apple said its “international growth is creating jobs

domestically, since we oversee most of our operations from California.”

“The vast majority of our global work force remains in the U.S.,” the statement

continued, “with more than 47,000 full-time employees in all 50 states.”

Moreover, Apple has given nearby Stanford University more than $50 million in

the last two years. The company has also donated $50 million to an African aid

organization. In its statement, Apple said: “We have contributed to many

charitable causes but have never sought publicity for doing so. Our focus has

been on doing the right thing, not getting credit for it. In 2011, we

dramatically expanded the number of deserving organizations we support by

initiating a matching gift program for our employees.”

Still, some, including De Anza College’s president, Mr. Murphy, say the

philanthropy and job creation do not offset Apple’s and other companies’

decisions to circumvent taxes. Within 20 minutes of the financially ailing

school are the global headquarters of Google, Facebook, Intel, Hewlett-Packard

and Cisco.

“When it comes time for all these companies — Google and Apple and Facebook and

the rest — to pay their fair share, there’s a knee-jerk resistance,” Mr. Murphy

said. “They’re philosophically antitax, and it’s decimating the state.”

“But I’m not complaining,” he added. “We can’t afford to upset these guys. We

need every dollar we can get.”

Additional reporting was contributed by Keith Bradsher in Hong

Kong,

Siem Eikelenboom in Amsterdam, Dean Greenaway in the British

Virgin Islands,

Scott Sayare in Luxembourg and Jason Woodard in Singapore.

How Apple Sidesteps Billions in Taxes, NYT,

28.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/business/apples-tax-strategy-aims-at-low-tax-states-and-nations.html

U.S. Growth Slows to 2.2%, Report Says

April 27, 2012

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

The economic recovery slowed more than expected early this

year, raising fears of a spring slowdown for the third year in a row and giving

Republicans a fresh opportunity to criticize President Obama’s policies.

The United States gross domestic product grew at an annual rate of 2.2 percent

in the first quarter, down from 3 percent at the end of last year, according to

a preliminary report released Friday. It was the first deceleration in a year,

but it was not nearly as severe as other setbacks in the last couple of years.

Mitt Romney, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, has been hammering

on economic issues all week, insisting that the president has held back the

recovery and intends to do further damage.

But the White House focused on the bright spots in the report, like solid growth

in consumer spending and a surge in residential building.

“When you look at the report in the totality, I think it shows that the private

sector is continuing to heal from the financial crisis,” said Alan Krueger,