|

History > 2009 > USA > War > Afghanistan (VI)

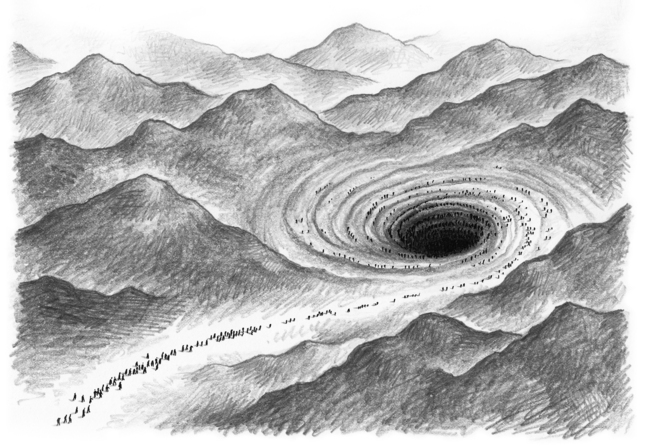

Illustration: Christophe Vorlet

Our Timeline, and the Taliban’s

NYT

4.12.2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/04/

opinion/04hastings.html

Op-Ed Columnist

Doubts About Certitude

December 16, 2009

The New York Times

By MAUREEN DOWD

It is the greatest example of the Law of Unintended Consequences.

In a bit of unpoetic justice, Bob Gates helped create the mess in Afghanistan

decades ago and now has to try to clean it up.

At the C.I.A. in the ’80s, Gates conspired with Charlie Wilson and the Saudis to

help the insurgents in Afghanistan turn back the occupation of a superpower. Now

he’s guiding the attempt of the occupying superpower to turn back the

insurgents, some of whom are the same ones he armed to defeat the Soviet Union.

Trying to do a good thing that also seemed like a strategically brilliant thing

— help the Afghan Davids repel the raw aggression of the Soviet Goliaths — we

created the monsters that have come back to haunt us, and we learned how little

control we have over history.

We trained a whole generation of jihadists and armed them. We paved the way for

the Taliban takeover and the rise of Osama bin Laden. We created the Islamist

power in the northwest frontier of Pakistan, swelled by millions of Afghan

refugees. We enabled the conditions for bin Laden’s safe haven. We contributed

to the instability of Pakistan.

On a rainy day in Kabul last week, I watched Gates climb into the cockpit of a

Soviet-era helicopter that Americans use to teach Afghans how to fly. The

defense secretary was in one of the same style Mi-17s that he once provided

Stinger missiles to shoot down. The absurdity was not lost on Gates, an avid

history reader who feels our foreign policy has too often been “an exercise in

misread history.”

Gates promised that America would not repeat its disappearing act of 1989.

Flying from Kabul to Iraq, I asked him if, like Paul Wolfowitz with the Iraqi

Shiites, he was driven to war because of guilt at abandoning people we had

promised to stand by.

“I don’t feel guilt about it, but we made a strategic mistake,” he said. “And it

wasn’t just the Afghans. At almost the same time, we basically cut off our

relationship with the Pakistanis. And the mistrust that exists today is a

reflection of that action on our part.”

I asked what he learned in the exhaustive White House review. He said Gen.

Stanley McChrystal, the top American commander in Afghanistan, convinced him

that “it was less the size of the force footprint than what the forces did on

the ground.” The Soviets, he added, “invaded a country.” Well, so did we. But

the Soviets, he said, killed a million Afghans and tried to impose “an alien

culture.”

But Gates knows messy conflicts get messier. When we were in Kabul, a senior

NATO commander conceded that civilians may have been killed during a joint

military operation with Afghan forces.

There is a brief window of opportunity when a benign occupying power can

accomplish some good before it is regarded with resentment and resistance.

I showed Gates an article in the newspaper Stars and Stripes reporting that U.S.

trainers considered Afghan soldiers and police a long way from ready, and that

some Afghans in a new unit in Baghlan Province cower in ditches, steal U.S. fuel

and weapons and are suspected of collaborating with the Taliban.

Capt. Jason Douthwaite, a logistics officer in Baghlan, told the military paper

that he felt more like an investigating officer than a mentor: “It’s not, ‘Let

me teach you your job.’ It’s more like, ‘How much did you steal from the

American government today?’ ”

Given the warping effect of ego in Washington, I asked the defense secretary how

he ensures that he doesn’t turn into Robert McNamara?

“I’ve never believed that I was the smartest guy in the room,” he said. “I want

people around me to tell me if they think I’m headed in the wrong direction. And

I read a lot.”

Gates laughs at being called an Eeyore, but he believes “too often there is a

desire for certitude where it’s not possible.” Harking back to Cold Warriors who

thought there could be a limited nuclear war, he demurred, “once things start,

how you get control of it or keep control of it struck me as just inherently a

problem.”

W. said invading Iraq could help break the cycle of supporting corrupt

dictators. But watching the Karzais acting like a mob family going to the

mattresses, how do we know we’re not simply creating and propping up another

corrupt dictator?

“You have to be realistic about the fact that developments of the kind we want

to see take time,” Gates replied. “If we can re-empower the traditional local

centers of authority, the tribal shuras and elders and things like that and put

an overlay of human rights on that, isn’t that a step in the right direction?

“I’m leery of trying to change history in dramatic, short strokes. I think it’s

very risky.”

Doubts About Certitude,

NYT, 16.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/16/opinion/16dowd.html

House Passes Defense Bill,

Rushes Toward Recess

December 16, 2009

Filed at 2:02 p.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

WASHINGTON (AP) -- The House has passed a $636 billion Pentagon spending bill

that funds the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and provides a 3.4 percent pay hike

for military personnel.

Approving the defense bill was one of several major must-do tasks the House must

address before its planned adjournment for the year at the end of the day.

To accomplish that, Democratic leaders attached to the defense bill numerous

temporary extensions of programs about to expire at the end of the year. Those

included two-month extensions for federal highway programs and unemployment

benefits.

The defense bill includes $128 billion for the war efforts in Iraq and

Afghanistan, but does not have money for the troop surge in Afghanistan recently

ordered by President Barack Obama.

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS UPDATE. Check back soon for further information. AP's

earlier story is below.

WASHINGTON (AP) -- The House launched a frenetic day of legislating Wednesday,

seeking to wrap up such end-of-session tasks as financing the military, helping

the jobless and permitting the government to run up more debt.

Lawmakers, with one eye on the door, plan to conclude the day with a vote on a

$174 billion jobs bill combining help for state and local governments with

spending on infrastructure and extended benefits for the jobless. Half of that

comes from diverting money from the Wall Street bailout fund.

''We've already put more than enough into shoring up Wall Street. Now we need to

focus on creating jobs for the Americans that will rebuild our economy from the

bottom up,'' said Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-Maine.

While House members look to vacations and trips to Copenhagen for the climate

summit, the Senate is likely to work into Christmas week as Democrats make their

final push to pass a health care overhaul bill.

The Senate won't take up the jobs bill until next year and much of Wednesday's

House action would simply postpone until early next year a host of difficult

issues, such as long-term financing of highway and other infrastructure projects

and dealing with controversies surrounding the anti-terror USA Patriot Act.

An exception is the $636 billion Pentagon budget bill, which has been held back

to serve as a locomotive to tug a bunch of unrelated provisions into law as

Congress rushes to finish its work in the dwindling days of this year.

The defense bill includes $128 billion to finance the war efforts in Iraq and

Afghanistan, but does not pay for the increase in troop strength in Afghanistan

recently ordered by President Barack Obama.

Other measures to be included in the defense bill include two-month extensions

of federal jobless benefits approved as part of the economic stimulus package in

February, health insurance subsidies for the unemployed and several provisions

of the Patriot Act that are set to expire.

The spate of two-month extensions is required because the House and Senate have

simply run out of time to iron out Congress' typical flood of year-end business,

as the notoriously balky Senate is tied up with the health care overhaul bill.

''In a world of alternatives, that's the one we have,'' said House Majority

Leader Steny Hoyer, D-Md., acknowledging that the need to revisit so many

controversial items early next year will be a huge headache for Democrats, who

control Congress.

Particularly troublesome is must-pass legislation to make sure the government

doesn't default on its obligations when it hits its $12.1 trillion limit on

borrowing in the coming days. The bill would boost the ceiling by $290 billion,

giving the Treasury another six weeks of borrowing power before Congress will

have to act again.

Plans for a far bigger increase in the federal debt limit that would have

ensured lawmakers didn't have to vote on it before next year's midterm elections

fell through.

Democratic leaders had proposed a huge increase of about $1.8 trillion, but ran

into trouble from fiscal conservatives in their own party, particularly Senate

moderates who wanted to tie the ceiling increase to creation of a task force on

deficit reduction.

Hoyer also said the House will approve a stopgap measure to ensure that the

Pentagon isn't deprived of money because of congressional delays in approving

the defense bill.

House action on all those bills would conclude its major tasks for the year. It

still would have to wait for the Senate, where debate could spill over into

Christmas week, depending on Senate action on the health care bill.

A host of tax issues would be ignored entirely, including action to prevent the

estate tax from expiring Jan. 1. The tax is set to disappear in 2010 but return

in 2011 at a rate of 55 percent for estates over $1 million. Also off the agenda

is the extension of about 30 business-related tax breaks that will end Dec. 31.

It's expected that Congress will have to act retroactively to address these tax

issues next year.

Action on the defense bill would close out congressional action on 12 spending

bills to fund agency operating budgets for the fiscal year that began Oct. 1.

------

On the Net:

Congress: http://thomas.loc.gov

House Passes Defense

Bill, Rushes Toward Recess, NYT, 16.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/12/16/us/politics/AP-US-Congress.html

Legislator Sees Echoes of Vietnam

in Afghan War

December 13, 2009

The New York Times

By SHERYL GAY STOLBERG

WASHINGTON — David R. Obey has served in Congress since Barack Obama was in

grade school. He does not waste time with pleasantries, and he does not mince

words. So when President Obama called Representative Obey recently to talk about

Afghanistan, the congressman raised a topic sure to make the young commander in

chief uncomfortable: Vietnam.

“I came here in ’69, and I determined that I would give Nixon a year to see what

he could do, because he had inherited the war, so I bit my tongue for a year,”

Mr. Obey said, recounting how he reminded the current president of the mistakes

of that earlier war. “I said the same thing with Obama.”

In fact, Mr. Obey, a Wisconsin Democrat, did not wait quite a year — Mr. Obama

has been in office just 11 months. And his is not an isolated complaint. As the

third-most senior member of the House, Mr. Obey gives voice to what Speaker

Nancy Pelosi calls the “serious unrest” in her caucus over Mr. Obama’s troop

buildup plan for Afghanistan. And as chairman of the House Appropriations

Committee, which controls how tax money is spent, he is in a position to

constrain the president through the power of the purse.

With the president estimating that the buildup will cost $30 billion, Mr. Obey

is proposing a “war surtax.” The idea is unlikely to pass, but it is already

reminding the nation of the high cost of an increasingly unpopular war. At the

White House, officials are bracing for the president’s first real battle with

fellow Democrats.

“We have some work to do,” conceded Rob Nabors, a former top aide to Mr. Obey

who is now the deputy director of the White House Office of Management and

Budget. “Other people talk about forcing the administration to jump through

hoops. Mr. Obey is not going to force us to jump through hoops, but he is going

to force us to confront some of the most uncomfortable questions having to do

with Afghanistan, and he’ll force us to do it in a very public setting.”

The debate could get its first real airing on Capitol Hill this week, when

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates

appear before members of the appropriations panel to testify on the new

Afghanistan strategy and its cost. The hearing will be led by Representative

John P. Murtha, a Pennsylvania Democrat who, like Mr. Obey, supports a war tax.

“Obama is going to have to do a real sales job,” said Steve Elmendorf, a

Democratic lobbyist who spent years as a senior aide on Capitol Hill. “You have

people who are uncomfortable with the policy, and people who are uncomfortable

with how to pay for it. And Obey, as chairman of the committee that holds the

purse strings, is uncomfortable with both.”

At 71, Mr. Obey (pronounced OH-bee), who represents the rural northwest corner

of Wisconsin, is something of a character on Capitol Hill. With a beard and

bifocals, he has the slightly rumpled look of the college professor he once

aspired to be. (He was pursuing a graduate degree in Russian studies when he

left academia for politics.) When he is animated, as is often the case, he tends

to squint and lace his conversation with mild profanity, as in, “I am damn tired

of a situation in which only military families are asked to pay any price

whatsoever for this war.”

Even his friends call him prickly, and he is prone to scuffles with colleagues.

Once, Mr. Obey so irritated Tom DeLay, the former House Republican leader, that

Mr. DeLay shoved him. “Pushing me,” Mr. Obey said wryly, “is not the worst thing

Tom DeLay ever did for this institution.”

He relaxes by playing the harmonica (he is in a band called the Capitol

Offenses); his rendition of “Amazing Grace” at a friend’s funeral “had everybody

in tears,” said Gov. James E. Doyle of Wisconsin. His aides are fiercely loyal.

“People around him put up with his peculiarities,” said Scott Lilly, who spent

nearly 30 years with Mr. Obey, “because they really do like him.”

In Congress, Mr. Obey has spent decades championing federal spending on health,

education and social programs, an agenda rooted in his Catholic faith, which, he

has said, demands that he try to “make this an equal society for everybody.” A

campaign poster of Franklin Roosevelt — “my hero,” he says — looks over his

shoulder in his sun-streaked Capitol office, where a window offers testimony to

his power: a view of the Washington monument.

“The main thing for Obey is his longstanding commitment to the domestic policies

that he cares about, especially when the competition for the money is a war he

disagrees with,” said David Canon, a professor of political science at the

University of Wisconsin.

So at a time when Congress “has been lectured ad nauseam” about paying for a

health care overhaul without raising the deficit, Mr. Obey says the same

standard must be applied to the war. He knows he will have difficulty getting

his surtax passed; Ms. Pelosi opposes it. But he will have little trouble

getting Democrats to scrutinize the president’s war budget request.

“His questions are very similar to those within our caucus: Do we have credible

partners in Afghanistan and Pakistan? What is the mission? What’s the risk?”

said Representative Rosa DeLauro, a Connecticut Democrat and member of the House

leadership. She sees the surtax as Mr. Obey’s way of forcing the nation to think

about “shared sacrifice,” adding, “He’s a smart, savvy legislator.”

But Mr. Obey is also a loyal Democrat, which puts him in a ticklish position.

Before he proposed the surtax, he called Mr. Nabors to give the president a

heads-up. That resulted in the president’s call. Mr. Obey used the conversation

to ask the president if he had seen a documentary by the public television

journalist Bill Moyers featuring archival audiotapes of President Lyndon B.

Johnson wrestling with escalating the Vietnam War.

“It is stunning,” he remembers telling Mr. Obama, “to listen to Johnson talk to

Dick Russell, the conservative old wise head in the Senate from Georgia — it is

terrible, gut-wrenching to listen to them both say, ‘Well, we know this is damn

near a fool’s errand, but we don’t have any choice.’ ”

If Mr. Obama objected, he did not say. But in a speech at West Point outlining

his Afghanistan strategy, he pointedly rejected the Vietnam analogy, saying it

“depends on a false reading of history.”

Mr. Obey came away from the speech unconvinced that Mr. Obama’s strategy could

succeed — not because he doubts the president, he said, but because he has

little faith in the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan. After 40 years in

Congress, a career that has spanned eight presidents, he is not about to quit

asking questions now.

“I didn’t come here to be Richard Nixon’s congressman, Reagan’s congressman,

Obama’s congressman,” Mr. Obey said. “I’m here representing the Seventh District

of Wisconsin.”

Legislator Sees Echoes

of Vietnam in Afghan War, NYT, 13.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/13/us/politics/13obey.html

Military Memo

Defense Secretary’s Trip

Encounters Snags

in Two Theaters

December 13, 2009

The New York Times

By ELISABETH BUMILLER

ERBIL, Iraq — It is an axiom of war that no battle plan ever survives the

first encounter with the enemy, but the travel plans of the defense secretary

last week barely survived encounters with his own troops and allies.

No one in the entourage of Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates was calling the

trip a metaphor for the mire ahead in Afghanistan, but no one was calling it a

previctory lap either. As Mr. Gates told troops in Iraq, previewing the infusion

of 30,000 new American troops to Afghanistan: “I think it will look a lot like

the surge here in the first six or eight months of 2007. The first six to eight

months were pretty tough here.”

The trip’s snags played out through the week and across both theaters of war.

Mr. Gates found himself grounded by weather in Kabul, stood up by the prime

minister in Baghdad and startled by President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan, who

blurted out at a palace news conference that the Afghans would not be able to

pay for their own security forces until 2024.

The timing of Mr. Karzai’s pronouncement was not ideal: this coming week Mr.

Gates has been summoned to explain to Congress the expected $30 billion a year

it will cost for the escalation of the Afghan war.

Mr. Gates, who maintained his usual laconic reserve as the disarray unfolded,

was by Friday more openly reflective when he acknowledged to American troops in

Kirkuk, the oil-rich region north of Baghdad, how hard a sell the wars were at

home. “One of the myths in the international community is that the United States

likes war,” he said. “And the reality is, other than the first two or three

years of World War II, there has never been a popular war in America.”

The first leg of his trip was to Afghanistan, but a cold fog that enveloped

Kabul on Wednesday delayed Mr. Gates from flights to see Afghan troops outside

the city and to talk to American soldiers at a besieged base in the Taliban

heartland of Kandahar. To pass the time, his staff arranged a tour of the new

NATO command center at the Kabul airport, which gave a sense of the growing

scale of the conflict: in a darkened former gymnasium dominated by enormous

video screens, more than 150 people at computer terminals took in battlefield

reports from around Afghanistan and monitored the war around the clock.

Then Mr. Gates got the word: there was enough visibility to fly. He headed out

to a waiting fleet of helicopters, got within steps of a Black Hawk and was told

to wait once again. Time passed, the sky grew murkier, but word rumbled among

his entourage on the tarmac that it would soon be a go. Mr. Gates wandered over

to a group of reporters. “I hope they know what they’re doing,” he said.

Moments later, Lt. Gen. David M. Rodriguez, the NATO and American second in

command in Afghanistan, made a slashing motion across his throat: the defense

secretary was grounded. Another time-filler was improvised: Mr. Gates popped in

to talk to employees at the fortress-like American Embassy, but he did not stop

in at the bar, a trailer on the embassy grounds called The Duck and Cover.

In Baghdad on Thursday the skies were clear, but Mr. Gates landed in the middle

of a raging political crisis for Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, who was

defending his record on security before an Iraqi Parliament incensed by five

devastating bombing attacks earlier in the week. Held up before the lawmakers

for six hours, Mr. Maliki canceled a meeting with Mr. Gates, who returned to

Camp Victory, the sprawling United States military headquarters in Baghdad,

where he dined with top commanders and then smoked cigars with them on the patio

of one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces overlooking a mucky artificial lake.

Mr. Gates did meet with Mr. Maliki early on Friday, the same day he finally

managed to talk to some troops. That was in Kirkuk, where in a town hall-style

session he was asked unusually pointed questions. Why, one wanted to know, is

the United States still at war after eight years?

“I think it’s a mistake to look at Afghanistan as sort of one eight-year war,”

Mr. Gates responded in the same even tone he had used all week. “We had a war in

2001, 2002, which we essentially won. And the Taliban was kicked out of

Afghanistan. Al Qaeda was kicked out of Afghanistan, many of them killed. And

then things were very quiet in Afghanistan.”

Without blaming President George W. Bush’s administration, which he once served,

for sidelining the conflict in favor of Iraq, Mr. Gates said the second war in

Afghanistan started in late 2005 and early 2006. “But the United States really

has gotten its head into this conflict in Afghanistan, as far as I’m concerned,

really only in the last year,” he said.

Late Friday, Mr. Gates returned to Washington after what his staff acknowledged

was a very hard week. But it was nothing, they said, compared with the marathon

in Afghanistan that lies ahead.

Defense Secretary’s Trip

Encounters Snags in Two Theaters, NYT, 13.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/13/world/13pentagon.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Obama’s Condolence Problem

December 12, 2009

The New York Times

By PAUL STEINBERG

WASHINGTON

THE recent revelation that the families of service members who are suicides do

not receive presidential condolence letters created a stir, evoking questions of

fairness and raising concerns about a lack of compassion from our leaders.

Yet the issue is far more complicated than that. Indeed, there is nothing wrong

with stigmatizing suicide while doing everything possible to de-stigmatize the

help soldiers need in dealing with post-traumatic stress and suicidal thoughts.

The key question is to what extent any action we take after a suicide

inadvertently glorifies it. Early Christians realized that they were losing too

many believers to the attractions of martyrdom. A halt to this epidemic of

provoking martyrdom by suicide was brought about in the fourth century when St.

Augustine codified the church’s disapproval of suicide and condemned the taking

of one’s own life as a grievous sin.

Canonical law ultimately pushed civil law in too harsh a direction. Only in 1961

did England repeal its law making suicide a crime. As late as 1974 in the United

States, suicide was still considered a crime in eight states.

Has the pendulum swung too far in the other direction? Now that first-rate

treatments for depression and post-traumatic stress have evolved and are readily

available, and people with emotional problems do not have to suffer quietly, are

we taking away the shame of suicide?

For more than 30 years, we in the mental-health field have been aware of the

prevalence of copycat suicides. Whenever the news of a well-known figure killing

himself hits the front pages, a significant bump in suicides, reflecting copycat

deaths, invariably follows in the next few days. Strikingly, there is no

corresponding decline in suicides in the weeks after this bump — forcing us to

conclude that the victims are people who would not have otherwise killed

themselves.

The hard truth is that any possible glorification of suicide — even reports of

suicide — make the taking of one’s life a more viable option. If suicide appears

to be a more reasonable way of handling life’s stresses than seeking help, then

suicide rates increase.

Certainly, a presidential condolence letter after one’s death is not exactly the

same encouragement for suicide as the purported Muslim promise of a gift of 72

virgins after death. But the increasing number of suicides in the military

suggests that we need to find the right balance between concern for the spouses,

children and parents left behind, and any efforts to prevent subsequent suicides

in the military.

As a psychiatrist formerly working on college campuses, I, along with my

colleagues, was concerned with how we handled the funerals and aftermaths of

even accidental deaths of students. Compassion for those left behind arose

naturally; at the same time, we did not want to glorify the death to a point

that lonely, distressed students might consider death better than life.

A difficult balancing act, to be sure. For people under 30, suicide is highly

correlated with impulsivity and suggestibility. Thus college campuses and

military installations, with their young populations, must be particularly aware

of the possibility of copycat suicides and the dangers of a veneration of death.

President Obama, as commander in chief, has to balance the wishes of families

with the demands of public health. In light of the condolence-letter

controversy, the administration is appropriately reviewing the policy that has

been in place for at least 17 years — and may indeed want to consider leaving it

as it is. But as a country, let’s focus our energies on doing everything we can

to diminish inadvertent incentives that might increase self-inflicted deaths.

Paul Steinberg, a former director of the counseling and psychiatric service

at Georgetown University, is a psychiatrist.

Obama’s Condolence

Problem, NYT, 12.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/12/opinion/12steinberg.html

2 Top Aides Show Unity to Congress

on Afghan Strategy

December 9, 2009

The New York Times

By ERIC SCHMITT

WASHINGTON — The two ranking Americans in Afghanistan, a soldier and a

diplomat, publicly put aside their differences and told Congress on Tuesday that

they fully supported President Obama’s new strategy to add 30,000 troops there

to reverse Taliban gains and prepare Afghans to better control their own

country.

The officials, Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, the top military commander in the

country, and Karl W. Eikenberry, the United States ambassador to Afghanistan,

began a full day of hearings before the House and Senate cautioning lawmakers of

the high costs — in lives as well as dollars — still to come in a war already

eight years old, but expressed faith in the new battle plan that Mr. Obama

announced last week after a three month review.

“The decisions that came from that process reflect a realistic and effective

approach,” General McChrystal said in his prepared remarks. “The mission is not

only important; it is also achievable. We can and will accomplish this mission.”

Ambassador Eikenberry, a retired three-star Army general and former commander in

Afghanistan himself, said that that administration for the first time was

providing adequate resources and attention to non-military goals — governance

and development — that ultimately would gauge the mission’s success.

“Our overarching goal is to encourage good governance, free from corruption, so

Afghans see the benefits of supporting the legitimate government, and the

insurgency loses support,” Ambassador Eikenberry said in his prepare remarks.

Both men, sitting beside each other before a battery of cameras, sought from the

outset to defuse any awkward tension that might have been displayed between two

colleagues who are said to have become rivals as they staked out conflicting

positions on the war’s course. They called each other “old friends,” even though

colleagues say they’ve been anything but in recent days.

“General McChrystal and I are united in a joint effort in which civilian and

military personnel work together every day, often literally side-by-side with

our Afghan partners and allies,” Ambassador Eikenberry said in his statement.

In fact, neither man got exactly what he wanted from Mr. Obama’s review, at

least in terms of troops. General McChrystal favored as many as an additional

40,000 forces, while Ambassador Eikenberry, according to people who read the

classified diplomatic cables he sent back to Washington, opposed any significant

increase until the Afghan government aggressively demonstrated its seriousness

in tackling governance, corruption and development problems.

In Tuesday morning’s hearing before the House Armed Services Committee, both

officials aimed to put the expansion to 100,000 American troops by late next

year in the context of three decades of civil war in Afghanistan. A hearing

before the Senate Armed Services Committee was to follow.

“While U.S. forces have been at war in Afghanistan for eight years, the Afghans

have been at it for more than 30,” General McChrystal said in his remarks. “They

are frustrated with international efforts that have failed to meet their

expectations, confronting us with a crisis of confidence among Afghans who view

the international effort as insufficient and their government as corrupt or, at

the very least, inconsequential.”

That said, Ambassador Eikenberry noted that the government of President Hamid

Karzai must aggressively fight corruption and work closely with the United

States to build able governance and competent Afghan security forces that

eventually can take over the fight against the Taliban.

“We expect the Afghan government to take specific actions in the key areas of

security, governance and economic development on an urgent basis,” Ambassador

Eikenberry said in his prepared remarks. “In the eighth year of our involvement,

Afghans must progressively take greater responsibility for their own affairs.”

Each official restated the goals that Mr. Obama described to the nation last

week in his televised address from the United States Military Academy at West

Point, N.Y.: defeat al Qaeda and prevents its return to Afghanistan; disrupt and

degrade the Taliban insurgency; separate the militants from the Afghan people;

and strengthen Afghan’s security forces.

The additional 30,000 American forces to secure population centers and to train

Afghan security forces “will provide us the ability to reverse insurgent

momentum and deny the Taliban the access to the population they require to

survive,” General McChrystal said.

“This means we must reverse the Taliban’s current momentum and create the time

and space to develop Afghan security and governance capacity,” he added.

Both General McChrystal and Ambassador Eikenberry cast the enemy as a complex

and resilient insurgency. The most prominent threat to Mr. Karzai’s government

comes from the Afghan Taliban, led by Mullah Muhammad Omar, who ruled

Afghanistan until the American invasion in October 2001, after the Sept. 11

attacks, they said.

The Taliban and two other groups, the Haqqani network and Hezb-e Islami

Gulbuddin, draw support from “external elements” in Iran and Pakistan, have ties

with al Qaeda, and co-exist within narcotics and criminal networks, both fueling

and feeding off instability and insecurity in the region, General McChrystal

said.

“The hazard posed by extremists that operate on both sides of the border with

Pakistan,

with freedom of movement across that border, must be mitigated by enhanced

cross-border coordination and enhanced Pakistani engagement,” General McChrystal

said.

But both the general and the envoy said that new strategy would work and offered

several reasons why. One, the officials said, the Taliban does not have

widespread popular support in Afghanistan, and instead dominates much of the

countryside through fear and intimidation.

Second, with a battle-tested American force and a stream of new civilian

specialists entering the country, the officials said the American and foreign

allies have already started to help Afghans establish more effective security

and more credible governance. “This is not a force of rookies or dilettantes,”

General McChrystal said.

The officials rejected comparisons to the Soviet presence in Afghanistan in the

1980’s. “Afghans do not regard us as occupiers,” General McChrystal said. “They

do not wish for us to remain forever, yet they see our support as a necessary

bridge to future security and stability.”

Ambassador Eikenberry and General McChrystal warned that the United States will

suffer additional casualties as fresh troops pour into Taliban strongholds in

the southern and eastern portions of the country, and acknowledged that the

materiel cost, which administration officials have put at an additional $30

billion in the first year, will be steep.

“The mission in Afghanistan is undeniably difficult, and success will require

steadfast commitment and incur significant costs,” General McChrystal said.

Under Mr. Obama’s plan, the military will begin drawing down American forces in

July 2011, but the pace and size of that withdrawal will depend on conditions on

the ground.

“By the summer of 2011, it will be clear to the Afghan people that the

insurgency will not win, giving them the chance to side with their government,”

General McChrystal said.

“Our efforts are now empowered with a greater sense of clarity, capability,

commitment, and confidence,” he added.

Unlike the previous eight years, however, this campaign will aim to include a

much greater role for civilians. By early 2010, Ambassador Eikenberry said, the

United States will have almost 1,000 civilians from agencies as diverse as the

Federal Bureau of Investigation to the Agriculture Department in country. About

400 of those specialists will deploy to the field in support of security

missions, the ambassador said. A year ago, there were 67 civilians operating

outside of Kabul.

2 Top Aides Show Unity

to Congress on Afghan Strategy, NYT, 9.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/09/world/asia/09policy.html

Editorial

Pakistan and the War

December 8, 2009

The New York Times

President Obama has articulated a reasonably comprehensive strategy for

Afghanistan, but there is no chance of defeating the Taliban and Al Qaeda unless

Pakistan’s leaders stop temporizing (and in some cases collaborating) and get

fully into the fight.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, former President George W. Bush tried to buy off

Pakistan’s military leaders who pocketed billions of dollars in American aid and

continued to shelter the Taliban. Mr. Obama must demand more while finding ways

to bolster the country’s weak civilian leadership and soothe anti-American

furies.

In a world of difficult strategic and diplomatic challenges, this may well be

Mr. Obama’s toughest.

In his speech last week, Mr. Obama laid down a marker for Islamabad, declaring

“we cannot tolerate a safe haven for terrorists whose location is known and

whose intentions are clear.” In private, administration officials have been even

more explicit, warning Pakistani leaders that if they don’t act the United

States will, including with more attacks by unmanned aircraft.

Such strikes have killed several top extremists, but the program is hugely

unpopular in Pakistan and Mr. Obama must be judicious about expanding it. That

means three things: extremely careful targeting, no civilian casualties or as

few as possible, and no publicity.

Drones won’t be enough. Pakistan’s civilian and military leaders must finally be

persuaded that this is not just America’s war, it is central to their survival.

In recent months, the Pakistan Army has gone after Taliban fighters in the Swat

Valley and Waziristan. Yet the Army leadership is refusing to strike at the

heart of the Taliban command in Baluchistan Province.

In part, they are hesitating because of legitimate fears of retaliation. But

there are also many Pakistani officials — and not just in the intelligence

services — that continue to see the Taliban as an ally and long-term proxy to

limit India’s influence in Afghanistan. To change that thinking, Mr. Obama will

first have to persuade Pakistanis that the United States is in it for the long

haul this time. The president sent conflicting messages in his speech, promising

Pakistan a long-term partnership “built on a foundation of mutual interest,

mutual respect and mutual trust,” but also suggesting that there will be a quick

drawdown of American troops in Afghanistan.

Mr. Obama privately has promised Pakistani military and civilian leaders what

one aide described as a partnership of “unlimited potential” in which Washington

would consider any proposal Islamabad puts on the table. Congress has already

authorized a $7.5 billion aid package, over five years, for schools, hospitals

and other nonmilitary projects. But this won’t mean anything if it does not

follow through and actually finance the program. The White House should also

press Congress to pass long-stalled legislation to establish special trade

preference zones in Pakistan.

Presuming security needs can be met, President Obama should visit Pakistan so he

can tell Pakistanis directly that their fears of abandonment — or domination —

are unfounded. Mr. Obama also must keep nudging India and Pakistan to improve

relations. That may be the best hope for freeing up resources and mind-sets in

Pakistan for the fight against the extremists.

Mr. Obama told a small group of journalists at a White House lunch last week

that reducing tensions between the two nuclear rivals, though enormously

difficult, is “as important as anything to the long-term stability of the

region.” He is right.

Pakistan and the War,

NYT, 8.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/08/opinion/08tue1.html

Administration Presses Pakistan

to Fight Taliban

December 8, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID E. SANGER

and ERIC SCHMITT

WASHINGTON — The Obama administration is turning up the pressure on Pakistan

to fight the Taliban inside its borders, warning that if it does not act more

aggressively the United States will use considerably more force on the Pakistani

side of the border to shut down Taliban attacks on American forces in

Afghanistan, American and Pakistani officials said.

The blunt message was delivered in a tense encounter in Pakistan last month,

before President Obama announced his new war strategy, when Gen. James L. Jones,

Mr. Obama’s national security adviser, and John O. Brennan, the White House

counterterrorism chief, met with the heads of Pakistan’s military and its

intelligence service.

United States officials said the message did not amount to an ultimatum, but

rather it was intended to prod a reluctant Pakistani military to go after

Taliban insurgents in Pakistan who are directing attacks in Afghanistan.

For their part the Pakistanis interpreted the message as a fairly bald warning

that unless Pakistan moved quickly to act against two Taliban groups they have

so far refused to attack, the United States was prepared to take unilateral

action to expand Predator drone attacks beyond the tribal areas and, if needed,

to resume raids by Special Operations forces into the country against Al Qaeda

and Taliban leaders.

A senior administration official, asked about the encounter, declined to go into

details but added quickly, “I think they read our intentions accurately.”

A Pakistani official who has been briefed on the meetings said, “Jones’s message

was if that Pakistani help wasn’t forthcoming, the United States would have to

do it themselves.”

American commanders said earlier this year that they were considering expanding

drone strikes in Pakistan’s lawless tribal areas, but General Jones’s comments

marked the first time that the United States bluntly told Pakistan it would have

to choose between leading attacks against the insurgents inside the country’s

borders or stepping aside to let the Americans do it.

The recent security demands followed an offer of a broader strategic

relationship and expanded intelligence sharing and nonmilitary economic aid from

the United States. Pakistan’s politically weakened president, Asif Ali Zardari,

replied in writing to a two-page letter that General Jones delivered from Mr.

Obama. But Mr. Zardari gave no indication of how Pakistan would respond to the

incentives, which were linked to the demands for greatly stepped-up

counterterrorism actions.

“We’ve offered them a strategic choice,” one administration official said,

describing the private communications. “And we’ve heard back almost nothing.”

Another administration official said, “Our patience is wearing thin.”

Asked Monday about the exchange, Tommy Vietor, a White House spokesman, said,

“We have no comment on private diplomatic correspondence. As the president has

said repeatedly, we will continue to partner with Pakistan and the international

community to enhance the military, governance and economic capacity of

Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

The implicit threat of not only ratcheting up the drone strikes but also

launching more covert American ground raids would mark a substantial escalation

of the administration’s counterterrorism campaign.

American Special Operations forces attacked Qaeda militants in a Pakistani

village near the border with Afghanistan in early September 2008, in the first

publicly acknowledged case of United States forces conducting a ground raid on

Pakistani soil.

But the raid caused a political furor in Pakistan, with the country’s top

generals condemning the attack, and the United States backed off what had been a

planned series of such strikes.

During his intensive review of Pakistan and Afghanistan strategy, officials say,

Mr. Obama concluded that no amount of additional troops in Afghanistan would

succeed in their new mission if the Taliban could retreat over the Pakistani

border to regroup and resupply. But the administration has said little about the

Pakistani part of the strategy.

“We concluded early on that whatever you do with Pakistan, you don’t want to

talk about it much,” a senior presidential aide said last week. “All it does is

get backs up in Islamabad.”

During his speech at West Point last week, Mr. Obama said that “our success in

Afghanistan is inextricably linked to our partnership with Pakistan.” But for

the rest of the speech he referred to the country in the past tense, talking

about how “there have been those in Pakistan who’ve argued that the struggle

against extremism is not their fight, and that Pakistan is better off doing

little or seeking accommodation with those who use violence.”

He never quite said how his administration views the Pakistanis today, and two

officials said that Mr. Obama used that construction in an effort not to

alienate the current government or the army, led by Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani.

Even before Mr. Obama announced his decision last week, the White House had

approved an expansion of the C.I.A.’s drone program in Pakistan’s lawless tribal

areas. A missile strike from what was said to be a United States drone in the

tribal areas killed at least three people early Tuesday, according to Pakistani

intelligence officials, The Associated Press reported.

Pakistani officials, wary of civilian casualties and the appearance of further

infringement of national sovereignty, are still in discussions with American

officials over whether to allow the C.I.A. to expand its missile strikes into

Baluchistan for the first time — a politically delicate move because it is

outside the tribal areas. American commanders say this is necessary because

Mullah Omar, the Taliban leader who ran Afghanistan before the 2001 invasion,

and other Taliban leaders are hiding in Quetta, the capital of Baluchistan

Province.

Pakistani officials also voice concern that if the Pakistani Army were to

aggressively attack the two groups that most concern the United States — the

Afghan Taliban leaders and the Haqqani network based in North Waziristan — the

militants would respond with waves of retaliatory bombings, further undermining

the weak civilian government.

Publicly, senior American officials and commanders take note of that concern.

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton arrived in Pakistan in late October

with offers of a strategic partnership. But General Jones followed Mrs. Clinton

two weeks later carrying more sticks than carrots, American officials said.

Administration Presses

Pakistan to Fight Taliban, NYT, 8.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/08/world/asia/08policy.html

Gates Calls July 2011 the Beginning,

Not End, of Afghan Withdrawal

December 7, 2009

The New York Times

By BRIAN KNOWLTON

WASHINGTON — Perhaps only a “handful” of American troops will be leaving

Afghanistan in July 2011, the date President Obama has set to begin a gradual

withdrawal, Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates said in an interview broadcast

Sunday.

“We will have 100,000 forces, troops there,” Mr. Gates said on ABC’s “This

Week,” “and they are not leaving in July of 2011. Some, handful, or some small

number, or whatever the conditions permit, will begin to withdraw at that time.”

“I don’t consider this an exit strategy,” he continued, “This is a transition.”

He said it would begin in less-contested parts of Afghanistan before expanding

to the most obdurate Taliban strongholds, largely in the south and east.

The White House used appearances on the Sunday talk programs to convey that the

deadline would mark the start, not the end, of troop withdrawal. “2011 is not a

cliff, it’s a ramp,” Gen. James L. Jones, the national security adviser, said.

“And it’s when the effects of this increase will be, by all accounts, according

to our military commanders and our senior civilians, where we will be able to

see very, very visible progress and we’ll be able to make a shift,” General

Jones said on CNN’s “State of the Union.”

Mr. Gates and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, who unusually appeared

together on three Sunday programs, emphasized that the July 2011 date did not

signal a wholesale abandonment of Afghanistan that could further destabilize the

region.

They said it was important to impart a sense of urgency to the Afghan government

about the need to move expeditiously to assume responsibility for their own

security.

“We will not provide for their security forever,” Mr. Gates said.

But the message he and Mrs. Clinton conveyed also seemed meant for Pakistan,

which fears the reverberations of any overly hasty American pullout, and for

Republican critics of any notion of a fixed withdrawal deadline.

“We’re not going to be walking away from Afghanistan again,” Mrs. Clinton said.

“We did that before; it didn’t turn out very well.”

Mr. Gates also said that “I think it has been years” since American intelligence

had a good idea of the whereabouts of Osama bin Laden, though the Qaeda leader

is thought to be either in Pakistan’s rugged North Waziristan region or just

across the border in Afghanistan.

General Jones, also asked about Mr. bin Laden’s location, answered: “The best

estimate is that he is somewhere in North Waziristan, sometimes on the Pakistani

side of the border, sometimes on the Afghan side of the border.”

Both Secretaries Gates and Clinton favorably mentioned President Hamid Karzai’s

recent assurance that Afghan security forces could resume control of some

provinces within three years, and over the bulk of the country in five.

While the new strategy aims in part to lure lower-level Taliban fighters away,

partly through offers of jobs, Mrs. Clinton expressed doubt that key Taliban

leaders could be thus enticed. Any defecting Taliban member, she said, would

have to renounce al-Qaeda, forswear violence and vow to live by Afghan laws. As

to whether senior leaders would do that, she said, “I’m highly skeptical.”

Mr. Obama’s new strategy — built around the rapid deployment of 30,000

additional American troops and thousands more NATO forces — has faced some of

its toughest criticism from his fellow Democrats. It has received stronger, if

conditional, support from some Republicans.

Senator John McCain of Arizona, a Vietnam War veteran and member of the Armed

Services Committee, has generally supported Mr. Obama’s plan.

“I think he made the right decision,” he said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.” But the

mention of the July 2011 date, he said, had left policy makers throughout the

region — including in Pakistan and India — “trying to figure out whether,

really, they can go all in and support this effort.”

He and other Republicans fear that the 2011 date will encourage Taliban and

al-Qaeda forces to simply outwait their enemy.

The appearances by Mr. Gates and Clinton — two of the president’s most important

advisers, and also two of the more hawkish — appeared designed to explain the

withdrawal guideline.

“After saying that “some, a handful, or small number” of troops would leave in

July 2011, Mr. Gates added that further departures would come only when American

commanders on the ground assessed that local conditions had sufficiently

improved.

“We’re not talking about an abrupt withdrawal,” Mr. Gates said, “we’re talking

about that something that will take place over a period of time.”

But he also sought to prepare Americans, and their allies, for a short-term

increase in casualties.

“The tragedy is that the casualties will probably continue to grow, at least for

the time being,” he said, because, as during the so-called troop surge in Iraq,

the new coalition troops would be going to some of the most hostile parts of the

country.

Mr. Gates added, however, that “we’ll have an increase in casualties at the

front end of this process, but over time it’ll actually lead to fewer

casualties” as security grows.

Gates Calls July 2011

the Beginning, Not End, of Afghan Withdrawal, NYT, 7.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/07/world/asia/07policy.html

How Obama Came to Plan

for ‘Surge’ in Afghanistan

December 6, 2009

The New York Times

By PETER BAKER

WASHINGTON — On the afternoon he held the eighth meeting of his Afghanistan

review, President Obama arrived in the White House Situation Room ruminating

about war. He had come from Arlington National Cemetery, where he had wandered

among the chalky white tombstones of those who had fallen in the rugged

mountains of Central Asia.

How much their sacrifice weighed on him that Veterans Day last month, he did not

say. But his advisers say he was haunted by the human toll as he wrestled with

what to do about the eight-year-old war. Just a month earlier, he had mentioned

to them his visits to wounded soldiers at the Army hospital in Washington. “I

don’t want to be going to Walter Reed for another eight years,” he said then.

The economic cost was troubling him as well after he received a private budget

memo estimating that an expanded presence would cost $1 trillion over 10 years,

roughly the same as his health care plan.

Now as his top military adviser ran through a slide show of options, Mr. Obama

expressed frustration. He held up a chart showing how reinforcements would flow

into Afghanistan over 18 months and eventually begin to pull out, a bell curve

that meant American forces would be there for years to come.

“I want this pushed to the left,” he told advisers, pointing to the bell curve.

In other words, the troops should be in sooner, then out sooner.

When the history of the Obama presidency is written, that day with the chart may

prove to be a turning point, the moment a young commander in chief set in motion

a high-stakes gamble to turn around a losing war. By moving the bell curve to

the left, Mr. Obama decided to send 30,000 troops mostly in the next six months

and then begin pulling them out a year after that, betting that a quick jolt of

extra forces could knock the enemy back on its heels enough for the Afghans to

take over the fight.

The three-month review that led to the escalate-then-exit strategy is a case

study in decision making in the Obama White House — intense, methodical,

rigorous, earnest and at times deeply frustrating for nearly all involved. It

was a virtual seminar in Afghanistan and Pakistan, led by a president described

by one participant as something “between a college professor and a gentle

cross-examiner.”

Mr. Obama peppered advisers with questions and showed an insatiable demand for

information, taxing analysts who prepared three dozen intelligence reports for

him and Pentagon staff members who churned out thousands of pages of documents.

This account of how the president reached his decision is based on dozens of

interviews with participants as well as a review of notes some of them took

during Mr. Obama’s 10 meetings with his national security team. Most of those

interviewed spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal

deliberations, but their accounts have been matched against those of other

participants wherever possible.

Mr. Obama devoted so much time to the Afghan issue — nearly 11 hours on the day

after Thanksgiving alone — that he joked, “I’ve got more deeply in the weeds

than a president should, and now you guys need to solve this.” He invited

competing voices to debate in front of him, while guarding his own thoughts.

Even David Axelrod, arguably his closest adviser, did not know where Mr. Obama

would come out until just before Thanksgiving.

With the result uncertain, the outsize personalities on his team vied for his

favor, sometimes sharply disagreeing as they made their arguments. The White

House suspected the military of leaking details of the review to put pressure on

the president. The military and the State Department suspected the White House

of leaking to undercut the case for more troops. The president erupted at the

leaks with an anger advisers had rarely seen, but he did little to shut down the

public clash within his own government.

“The president welcomed a full range of opinions and invited contrary points of

view,” Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said in an interview last

month. “And I thought it was a very healthy experience because people took him

up on it. And one thing we didn’t want — to have a decision made and then have

somebody say, ‘Oh, by the way.’ No, come forward now or forever hold your

peace.”

The decision represents a complicated evolution in Mr. Obama’s thinking. He

began the process clearly skeptical of Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal’s request for

40,000 more troops, but the more he learned about the consequences of failure,

and the more he narrowed the mission, the more he gravitated toward a robust if

temporary buildup, guided in particular by Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates.

Yet even now, he appears ambivalent about what some call “Obama’s war.” Just two

weeks before General McChrystal warned of failure at the end of August, Mr.

Obama described Afghanistan as a “war of necessity.” When he announced his new

strategy last week, those words were nowhere to be found. Instead, while

recommitting to the war on Al Qaeda, he made clear that the larger struggle for

Afghanistan had to be balanced against the cost in blood and treasure and

brought to an end.

Aides, though, said the arduous review gave Mr. Obama comfort that he had found

the best course he could. “The process was exhaustive, but any time you get the

president of the United States to devote 25 hours, anytime you get that kind of

commitment, you know it was serious business,” said Gen. James L. Jones, the

president’s national security adviser. “From the very first meeting, everyone

started with set opinions. And no opinion was the same by the end of the

process.”

Taking Control of a War

Mr. Obama ran for president supportive of the so-called good war in Afghanistan

and vowing to send more troops, but he talked about it primarily as a way of

attacking Republicans for diverting resources to Iraq, which he described as a

war of choice. Only after taking office, as casualties mounted and the Taliban

gained momentum, did Mr. Obama really begin to confront what to do.

Even before completing a review of the war, he ordered the military to send

21,000 more troops there, bringing the force to 68,000. But tension between the

White House and the military soon emerged when General Jones, a retired Marine

four-star general, traveled to Afghanistan in the summer and was surprised to

hear officers already talking about more troops. He made it clear that no more

troops were in the offing.

With the approach of Afghanistan’s presidential election in August, Mr. Obama’s

two new envoys — Richard C. Holbrooke, the president’s special representative to

the region, and Lt. Gen. Karl W. Eikenberry, a retired commander of troops in

Afghanistan now serving as ambassador — warned of trouble, including the

possibility of angry Afghans marching on the American Embassy or outright civil

war.

“There are 10 ways this can turn out,” one administration official said, summing

up the envoys’ presentation, “and 9 of them are messy.”

The worst did not happen, but widespread fraud tainted the election and shocked

some in the White House as they realized that their partner in Kabul, President

Hamid Karzai, was hopelessly compromised in terms of public credibility.

At the same time, the Taliban kept making gains. The Central Intelligence Agency

drew up detailed maps in August charting the steady progression of the Taliban’s

takeover of Afghanistan, maps that would later be used extensively during the

president’s review. General McChrystal submitted his own dire assessment of the

situation, warning of “mission failure” without a fresh infusion of troops.

While General McChrystal did not submit a specific troop request at that point,

the White House knew it was coming and set out to figure out what to do. General

Jones organized a series of meetings that he envisioned lasting a few weeks.

Before each one, he convened a rehearsal session to impose discipline — “get rid

of the chaff,” one official put it — that included Vice President Joseph R.

Biden Jr., Mrs. Clinton, Mr. Gates and other cabinet-level officials. Mr. Biden

made a practice of writing a separate private memo to Mr. Obama before each

meeting, outlining his thoughts.

The first meeting with the president took place on Sept. 13, a Sunday, and was

not disclosed to the public that day. For hours, Mr. Obama and his top advisers

pored through intelligence reports.

Unsatisfied, the president posed a series of questions: Does America need to

defeat the Taliban to defeat Al Qaeda? Can a counterinsurgency strategy work in

Afghanistan given the problems with its government? If the Taliban regained

control of Afghanistan, would nuclear-armed Pakistan be next?

The deep skepticism he expressed at that opening session was reinforced by Mr.

Biden, who rushed back overnight from a California trip to participate. Just as

he had done in the spring, Mr. Biden expressed opposition to an expansive

strategy requiring a big troop influx. Instead, he put an alternative on the

table — rather than focus on nation building and population protection, do more

to disrupt the Taliban, improve the quality of the training of Afghan forces and

expand reconciliation efforts to peel off some Taliban fighters.

Mr. Biden quickly became the most outspoken critic of the expected McChrystal

troop request, arguing that Pakistan was the bigger priority, since that is

where Al Qaeda is mainly based. “He was the bull in the china shop,” said one

admiring administration official.

But others were nodding their heads at some of what he was saying, too,

including General Jones and Rahm Emanuel, the White House chief of staff.

A Review Becomes News

The quiet review burst into public view when General McChrystal’s secret report

was leaked to Bob Woodward of The Washington Post a week after the first

meeting. The general’s grim assessment jolted Washington and lent urgency to the

question of what to do to avoid defeat in Afghanistan.

Adm. Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Gen. David H.

Petraeus, the regional commander, secretly flew to an American air base in

Germany for a four-hour meeting with General McChrystal on Sept. 25. He handed

them his troop request on paper — there were no electronic versions and barely

20 copies in all.

The request outlined three options for different missions: sending 80,000 more

troops to conduct a robust counterinsurgency campaign throughout the country;

40,000 troops to reinforce the southern and eastern areas where the Taliban are

strongest; or 10,000 to 15,000 troops mainly to train Afghan forces.

General Petraeus took one copy, while Admiral Mullen took two back to Washington

and dropped one off at Mr. Gates’s home next to his in a small military compound

in Washington. But no one sent the document to the White House, intending to

process it through the Pentagon review first.

Mr. Obama was focused on another report. At 10 p.m. on Sept. 29, he called over

from the White House residence to the West Wing to ask for a copy of the first

Afghanistan strategy he approved in March to ramp up the fight against Al Qaeda

and the Taliban while increasing civilian assistance. A deputy national security

adviser, Denis McDonough, brought him a copy to reread overnight. When his

national security team met the next day, Mr. Obama complained that elements of

that plan had never been enacted.

The group went over the McChrystal assessment and drilled in on what the core

goal should be. Some thought that General McChrystal interpreted the March

strategy more ambitiously than it was intended to be. Mr. Biden asked tough

questions about whether there was any intelligence showing that the Taliban

posed a threat to American territory. But Mr. Obama also firmly closed the door

on any withdrawal. “I just want to say right now, I want to take off the table

that we’re leaving Afghanistan,” he told his advisers.

Tension with the military had been simmering since the leak of the McChrystal

report, which some in the White House took as an attempt to box in the

president. The friction intensified on Oct. 1 when the general was asked after a

speech in London whether a narrower mission, like the one Mr. Biden proposed,

would succeed. “The short answer is no,” he said.

White House officials were furious, and Mr. Gates publicly scolded advisers who

did not keep their advice to the president private. The furor rattled General

McChrystal, who, unlike General Petraeus, was not a savvy Washington operator.

And it stunned others in the military, who were at first “bewildered by how over

the top the reaction was from the White House,” as one military official put it.

It also proved to be what one review participant called a “head-snapping” moment

of revelation for the military. The president, they suddenly realized, was not

simply updating his previous strategy but essentially starting over from

scratch.

The episode underscored the uneasy relationship between the military and a new

president who, aides said, was determined not to be as deferential as he

believed his predecessor, George W. Bush, was for years in Iraq. And the

military needed to adjust to a less experienced but more skeptical commander in

chief. “We’d been chugging along for eight years under an administration that

had become very adept at managing war in a certain way,” said another military

official.

Moreover, Mr. Obama had read “Lessons in Disaster,” Gordon M. Goldstein’s book

on the Vietnam War. The book had become a must read in the West Wing after Mr.

Emanuel had dinner over the summer at the house of another deputy national

security adviser, Thomas E. Donilon, and wandered into his library to ask what

he should be reading.

Among the conclusions that Mr. Donilon and the White House team drew from the

book was that both President John F. Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson

failed to question the underlying assumption about monolithic Communism and the

domino theory — clearly driving the Obama advisers to rethink the nature of Al

Qaeda and the Taliban.

The Pakistan Question

While public attention focused on Afghanistan, some of the most intensive

discussion focused on the country where Mr. Obama could send no troops —

Pakistan. Pushed in particular by Mrs. Clinton, the president’s team explored

the links between the Afghan Taliban, the Pakistani Taliban and Al Qaeda, and

Mr. Obama told aides that it did not matter how many troops were sent to

Afghanistan if Pakistan remained a haven.

Many of the intelligence reports ordered by the White House during the review

dealt with Pakistan’s stability and whether its military and intelligence

services were now committed to the fight or secretly still supporting Taliban

factions. According to two officials, there was a study of the potential

vulnerability of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons, posing questions about potential

insider threats and control of the warheads if the Pakistani government fell.

Mr. Obama and his advisers also considered options for stepping up the pursuit

of extremists in Pakistan’s border areas. He eventually approved a C.I.A.

request to expand the areas where remotely piloted aircraft could strike, and

other covert action. The trick would be getting Pakistani consent, which still

has not been granted.

On Oct. 9, Mr. Obama and his team reviewed General McChrystal’s troop proposals

for the first time. Some in the White House were surprised by the numbers,

assuming there would be a middle ground between 10,000 and 40,000.

“Why wasn’t there a 25 number?” one senior administration official asked in an

interview. He then answered his own question: “It would have been too tempting.”

Mr. Gates and others talked about the limits of the American ability to actually

defeat the Taliban; they were an indigenous force in Afghan society, part of the

political fabric. This was a view shared by others around the table, including

Leon E. Panetta, the director of the C.I.A., who argued that the Taliban could

not be defeated as such and so the goal should be to drive wedges between those

who could be reconciled with the Afghan government and those who could not be.

With Mr. Biden leading the skeptics, Mrs. Clinton, Mr. Gates and Admiral Mullen

increasingly aligned behind a more robust force. Mrs. Clinton wanted to make

sure she was a formidable player in the process. “She was determined that her

briefing books would be just as thick and just as meticulous as those of the

Pentagon,” said one senior adviser. She asked hard questions about Afghan troop

training, unafraid of wading into Pentagon territory.

After a meeting where the Pentagon made a presentation with impressive

color-coded maps, Mrs. Clinton returned to the State Department and told her

aides, “We need maps,” as one recalled. She was overseas during the next meeting

on Oct. 14, when aides used her new maps to show civilian efforts but she

participated with headphones on from her government plane flying back from

Russia.

Mr. Gates was a seasoned hand at such reviews, having served eight presidents

and cycled in and out of the Situation Room since the days when it was served by

a battery of fax machines. Like Mrs. Clinton, he was sympathetic to General

McChrystal’s request, having resolved his initial concern that a buildup would

fuel resentment the way the disastrous Soviet occupation of Afghanistan did in

the 1980s.

But Mr. Gates’s low-wattage exterior masks a wily inside player, and he knew

enough to keep his counsel early in the process to let it play out more first.

“When to speak is important to him; when to signal is important to him,” said a

senior Defense Department official.

On Oct. 22, the National Security Council produced what one official called a

“consensus memo,” much of which originated out of the defense secretary’s

office, concluding that the United States should focus on diminishing the

Taliban insurgency but not destroying it; building up certain critical

ministries; and transferring authority to Afghan security forces.

There was no consensus yet on troop numbers, however, so Mr. Obama called a

smaller group of advisers together on Oct. 26 to finally press Mrs. Clinton and

Mr. Gates. Mrs. Clinton made it clear that she was comfortable with General

McChrystal’s request for 40,000 troops or something close to it; Mr. Gates also

favored a big force.

Mr. Obama was leery. He had received a memo the day before from the Office of

Management and Budget projecting that General McChrystal’s full 40,000-troop

request on top of the existing deployment and reconstruction efforts would cost

$1 trillion from 2010 to 2020, an adviser said. The president seemed in sticker

shock, watching his domestic agenda vanishing in front of him. “This is a

10-year, trillion-dollar effort and does not match up with our interests,” he

said.

Still, for the first time, he made it clear that he was ready to send more

troops if a strategy could be found to ensure that it was not an endless war. He

indicated that the Taliban had to be beaten back. “What do we need to break

their momentum?” he asked.

Four days later, at a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff on Oct. 30, he

emphasized the need for speed. “Why can’t I get the troops in faster?” he asked.

If they were going to do this, he concluded, it only made sense to do this

quickly, to have impact and keep the war from dragging on forever. “This is

America’s war,” he said. “But I don’t want to make an open-ended commitment.”

Bridging the Differences

Now that he had a sense of where Mr. Obama was heading, Mr. Gates began shaping

a plan that would bridge the differences. He developed a 30,000-troop option

that would give General McChrystal the bulk of his request, reasoning that NATO

could make up most of the difference.

“If people are having trouble swallowing 40, let’s see if we can make this

smaller and easier to swallow and still give the commander what he needs,” a

senior Defense official said, summarizing the secretary’s thinking.

The plan, called Option 2A, was presented to the president on Nov. 11. Mr. Obama

complained that the bell curve would take 18 months to get all the troops in

place.

He turned to General Petraeus and asked him how long it took to get the

so-called surge troops he commanded in Iraq in 2007. That was six months.

“What I’m looking for is a surge,” Mr. Obama said. “This has to be a surge.”

That represented a contrast from when Mr. Obama, as a presidential candidate,

staunchly opposed President Bush’s buildup in Iraq. But unlike Mr. Bush, Mr.

Obama wanted from the start to speed up a withdrawal as well. The military was

told to come up with a plan to send troops quickly and then begin bringing them

home quickly.

And in another twist, Mr. Obama, who campaigned as an apostle of transparency

and had been announcing each Situation Room meeting publicly and even releasing

pictures, was livid that details of the discussions were leaking out.

“What I’m not going to tolerate is you talking to the press outside of this

room,” he scolded his advisers. “It’s a disservice to the process, to the

country and to the men and women of the military.”

His advisers sat in uncomfortable silence. That very afternoon, someone leaked

word of a cable sent by Ambassador Eikenberry from Kabul expressing reservations

about a large buildup of forces as long as the Karzai government remained

unreformed. At one of their meetings, General Petraeus had told Mr. Obama to

think of elements of the Karzai government like “a crime syndicate.” Ambassador

Eikenberry was suggesting, in effect, that America could not get in bed with the

mob.

The leak of Ambassador Eikenberry’s Nov. 6 cable stirred another storm within

the administration because the cable had been requested by the White House. The

National Security Council had told the ambassador to put his views in writing.

But someone else then passed word of the cable to reporters in what some in the

process took to be a calculated attempt to head off a big troop buildup.

The cable stunned some in the military. The reaction at the Pentagon, said one

official, was “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” — military slang for an expression of

shock. Among the officers caught off guard were General McChrystal and his

staff, for whom the cable was “a complete surprise,” said another official, even

though the commander and the ambassador meet three times a week.

A Presidential Order

By this point, the idea of some sort of time frame was taking on momentum. Mrs.

Clinton talked to Mr. Karzai before the Afghan leader’s inauguration to a second

term. She suggested that he use his speech to outline a schedule for taking over

security of the country.

Mr. Karzai did just that, declaring that Afghan forces directed by Kabul would