|

History > 2009 > USA > Health (IV)

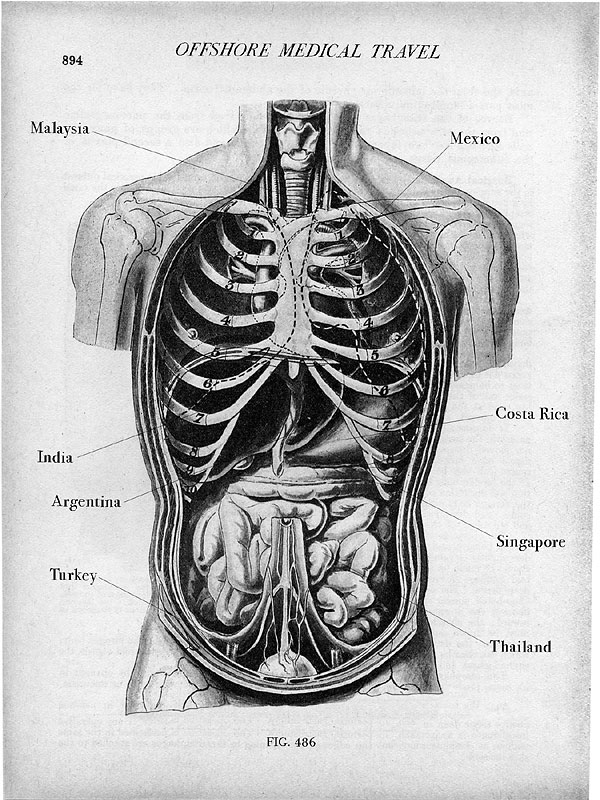

Illustration: Michael Schmellin

Overseas, Under the Knife

NYT

June 9, 2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/10/

opinion/10milstein.html

Grant System

Leads Cancer Researchers

to Play It Safe

June 28, 2009

The New York Times

By GINA KOLATA

Among the recent research grants awarded by the National Cancer Institute is

one for a study asking whether people who are especially responsive to

good-tasting food have the most difficulty staying on a diet. Another study will

assess a Web-based program that encourages families to choose more healthful

foods.

Many other grants involve biological research unlikely to break new ground. For

example, one project asks whether a laboratory discovery involving colon cancer

also applies to breast cancer. But even if it does apply, there is no treatment

yet that exploits it.

The cancer institute has spent $105 billion since President Richard M. Nixon

declared war on the disease in 1971. The American Cancer Society, the largest

private financer of cancer research, has spent about $3.4 billion on research

grants since 1946.

Yet the fight against cancer is going slower than most had hoped, with only

small changes in the death rate in the almost 40 years since it began.

One major impediment, scientists agree, is the grant system itself. It has

become a sort of jobs program, a way to keep research laboratories going year

after year with the understanding that the focus will be on small projects

unlikely to take significant steps toward curing cancer.

“These grants are not silly, but they are only likely to produce incremental

progress,” said Dr. Robert C. Young, chancellor at Fox Chase Cancer Center in

Philadelphia and chairman of the Board of Scientific Advisors, an independent

group that makes recommendations to the cancer institute.

The institute’s reviewers choose such projects because, with too little money to

finance most proposals, they are timid about taking chances on ones that might

not succeed. The problem, Dr. Young and others say, is that projects that could

make a major difference in cancer prevention and treatment are all too often

crowded out because they are too uncertain. In fact, it has become lore among

cancer researchers that some game-changing discoveries involved projects deemed

too unlikely to succeed and were therefore denied federal grants, forcing

researchers to struggle mightily to continue.

Take one transformative drug, for breast cancer. It was based on a discovery by

Dr. Dennis Slamon of the University of California, Los Angeles, that very

aggressive breast cancers often have multiple copies of a particular protein,

HER-2. That led to the development of herceptin, which blocks HER-2.

Now women with excess HER-2 proteins, who once had the worst breast cancer

prognoses, have prognoses that are among the best. But when Dr. Slamon wanted to

start this research, his grant was turned down. He succeeded only after the

grateful wife of a patient helped him get money from Revlon, the cosmetics

company.

Yet studies like the one on tasty food are financed. That study, which received

a grant of $100,000 over two years, is based on the idea that since obesity is

associated with an increased risk of cancer, understanding why people have

trouble losing weight could lead to better weight control methods, which could

lead to less obesity, which could lead to less cancer.

“It was the first grant I ever submitted, and it was funded on the first try,”

said the principal investigator, Bradley M. Appelhans, an assistant professor of

basic medical sciences and psychology at the University of Arizona. Dr.

Appelhans said he realized it would hardly cure cancer, but hoped that “it will

provide knowledge that will incrementally contribute to more effective cancer

prevention strategies.”

Even top federal cancer officials say the system needs to be changed.

“We have a system that works over all pretty well, and is very good at ruling

out bad things — we don’t fund bad research,” said Dr. Raynard S. Kington,

acting director of the National Institutes of Health, which includes the cancer

institute. “But given that, we also recognize that the system probably provides

disincentives to funding really transformative research.”

The private American Cancer Society follows a similarly cautious path. Last

year, it awarded $124 million in new research grants, with some money coming

from large donors but most from events like walkathons and memorial donations.

Dr. Otis W. Brawley, chief medical officer at the cancer society, said the whole

cancer research effort remained too cautious.

“The problem in science is that the way you get ahead is by staying within

narrow parameters and doing what other people are doing,” Dr. Brawley said. “No

one wants to fund wild new ideas.”

He added that the problem of getting money for imaginative but chancy proposals

had worsened in recent years. There are more scientists seeking grants — they

surged into the field in the 1990s when the National Institutes of Health budget

doubled before plunging again.

That makes many researchers, who need grants not just to run their labs but also

sometimes to keep their faculty positions, even more cautious in the grant

proposals they submit. And grant review committees become more wary about giving

scarce money to speculative proposals.

Philanthropies, which helped some researchers try outside-the-box ideas, are now

having financial problems. And advances in technology have made research more

expensive.

“Scientists don’t like talking about it publicly,” because they worry that their

remarks will be viewed as lashing out at the health institutes, which supports

them, said Dr. Richard D. Klausner, a former director of the National Cancer

Institute.

But, Dr. Klausner added: “There is no conversation that I have ever had about

the grant system that doesn’t have an incredible sense of consensus that it is

not working. That is a terrible wasted opportunity for the scientists, patients,

the nation and the world.”

A Big Idea Without a Backer

For 25 years, Eileen K. Jaffe received federal grants to run her lab. As a

senior scientist at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, with a long list of published

papers in prestigious journals, she is a respected, established researcher.

Then Dr. Jaffe stumbled upon results that went against textbook explanations,

suggesting that it might be possible to find an entirely new class of drugs that

could disable proteins that fuel cancer cells. Now she wants to find chemicals

that might be developed into such drugs.

But her grant proposal was rejected out of hand by the institutes of health, not

even discussed by a review panel. She had no preliminary data showing that the

idea was likely to work, something reviewers always want to see, and the idea

was just too unprecedented.

Dr. Jaffe epitomizes the scientist who realizes that if she were to

single-mindedly pursue her unorthodox idea, her “career may be ruined in the

process,” in the words of Dr. Brawley of the American Cancer Society.

Dr. Jaffe is just conceiving her project; it is much to soon to know whether it

will result in a revolutionary drug. And even if she does find potential new

drugs, it is not clear that they will be effective. Most new ideas are difficult

to prove, and most potential new drugs fail.

So Dr. Jaffe was not entirely surprised when her grant application to look for

such cancer drugs was summarily rejected.

“They said I don’t have preliminary results,” she said. “Of course I don’t. I

need the grant money to get them.”

Dr. Young, chancellor at Fox Chase, said Dr. Jaffe’s situation showed why people

with bold new ideas often just give up.

“You can’t prove it will work in advance,” he said. “If you could, it wouldn’t

be a high-risk idea.”

It is a long haul, Dr. Jaffe knows. And she has already had to downsize her lab.

But, she said, she will persist.

Angels Outside Government

At the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Dr. Ewa T. Sicinska knew she

would have a similar problem with her research. She wanted to grow human cancers

in mice. Unlike Dr. Jaffe, though, Dr. Sicinska did not even apply for

government money.

It is not that the project was unimportant.

“Rather than have to start a human clinical trial to test new drugs, we want to

test them first in mice with real human tumors,” said Dr. George D. Demetri, who

leads the research group supporting Dr. Sicinska.

Researchers have studied mouse cancers but, they acknowledge, they are just not

the same as human cancers — they are much easier to treat, and drugs that cure

mice often do nothing in people. So, over the years, scientists have tried to

implant human cancer cells in mice, but with little success.

“Everyone told us that if you take tumors out of patients and put them in mice,

they don’t grow,” Dr. Demetri said. The tumor cells usually were put in a

plastic dish before being implanted in mice. “We said — wait a minute. The cells

are not growing in the plastic dish. They probably are dying. What if we bypass

the dish?’”

With that idea in mind, Dr. Demetri, convinced it was too speculative to get

federal money, tapped an unusual source, the Ludwig Fund. Endowed by Daniel K.

Ludwig, one of the world’s richest men in the 1960s and 1970s, the fund supports

unfettered cancer research at six medical centers in the United States,

including Dana-Farber, to be used at the institutes’ discretion. That put Dr.

Sicinska in a very different position from that of Dr. Jaffe. She could try

something chancy without a grant.

Dr. Sicinska used a quarter of a million dollars of Ludwig money for this

project, buying mice without immune systems, which meant they could not reject

human tumors, and housing them in a germ-free basement lab. She spent months

learning to implant tumors in the mice and enlisted geneticists to study the

implanted tumors, making sure they did not mutate beyond recognition.

She spends her days in the lab, using a miniature ultrasound machine to scan the

mice, hairless creatures with prominent ears. Four types of sarcomas — cancers

of fat, muscle or bone — are growing in them and look genetically identical to

the tumors removed from patients.

Dr. Elias A. Zerhouni, former director of the National Institutes of Health,

said he was not sure that a grant for the project would have been turned down.

The N.I.H., he said, does finance research on mouse models for human cancer.

But Dr. Demetri said he did not apply “because we have lots of experience in

what’s fundable.” His mouse work, he said, is exploratory, and he cannot predict

what he will find or when. He certainly could not lay out a road map of what he

would do and promise results in a few years.

Studies With a Different Goal

Researchers like Dr. Appelhans, who is studying weight control and tasty foods,

do not expect to change the outlook for cancer patients anytime soon. But, they

say, that does not mean their work is unimportant.

Dr. Appelhans will study 85 overweight or obese women, measuring how much the

tastes and textures of food drive their eating. Then they will be given a weight

loss diet and nutritional counseling. Dr. Appelhans will ask whether those who

are most tempted by the tastes and textures also have the most trouble following

the diet.

As for the grant to assess a Web-based program to improve food choices, it is

predicated on studies indicating that what people eat in childhood and

adolescence may have an impact on cancer risk in middle and old age, said the

grant recipient, Karen Weber Cullen, associate professor of pediatrics at Baylor

College of Medicine. Some studies have found that people who reported having

eaten fruits and vegetables when they were younger and maintaining a healthy

weight were less likely to have cancer.

Of course, it would not be feasible to follow participants for 30 or 40 years to

see if their cancer risk was altered, Dr. Cullen noted. But, she added, “we try

to achieve improvements in diet and physical activity behaviors that become

permanent and will make a difference in later years.”

In the study asking whether a molecular pathway that spurs the growth of colon

cancer cells also encourages the growth of breast cancer cells, the principal

investigator ultimately wants to find a safe drug to prevent breast cancer. She

received a typical-size grant of a little more than $1 million for the five-year

study.

The plan, said the investigator, Louise R. Howe, an associate research professor

at Weill Cornell Medical College, is first to confirm her hypothesis about the

pathway in breast cancer cells. But even if it is correct, the much harder

research would lie ahead because no drugs exist to block the pathway, and even

if they did, there are no assurances that they would be safe.

Dr. Howe said she hoped that she would find such drugs, or that companies would.

Then she wants to develop a way to selectively deliver the drugs to precancerous

breast cells. If it all works and the treatment is safe, women with precancerous

conditions could avoid developing cancer.

Dr. Howe has reviewed grants for the cancer institute herself, she said, and

realizes that, among other things, those that get financed must have “a novel

hypothesis that is credible based on what we know already.”

Trying to Change the System

The National Institutes of Health has started “pilot experiments” to see if

there is a better way of getting financing for innovative projects, its acting

director, Dr. Kington, said.

They include “pioneer awards,” begun in 2004 for “ideas that have the potential

for high impact but may be too novel, span too diverse a range of disciplines or

be at a stage too early to fare well in the traditional peer review process.”

But only 3 percent to 5 percent of the applicants get funded. Now the institutes

have decided to set aside up to $25 million for “transformative R01 grants,”

described as “proposing exceptionally innovative, high risk, original and/or

unconventional research with the potential to create or overturn fundamental

paradigms.”

About 700 proposals have come in, but only a small number are expected to be

financed, according to Dr. Keith R. Yamamoto, a molecular biologist and

executive vice dean of the school of medicine at the University of California,

San Francisco, and co-chairman of the committee that reviewed the proposals last

week.

“From reading the applications so far, there are really some fantastic things,”

Dr. Yamamoto said.

There also is new money from the federal economic stimulus package passed by

Congress, which gives the National Institutes of Health $200 million for

“challenge grants” lasting two years or less.

But the N.I.H. has received about 21,000 applications for 200 challenge grants,

and researchers who have applied concede there is not much hope.

“I did submit one of these challenge grants recently, like the rest of the

lemmings,” said Dr. Chi Dang, professor of medicine, cell biology, oncology and

pathology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. But, he added,

“there are many, many more applications than slots.”

Some experienced scientists have found a way to offset the problem somewhat.

They do chancy experiments by siphoning money from their grants.

“In a way, the system is encrypted,” Dr. Yamamoto said, allowing those in the

know to wink and do their own thing on the side.

Great discoveries have been made with N.I.H. financing without manipulating the

system, Dr. Klausner said.

“But,” he added, “I actually believe that by and large it is despite, rather

than because of, the review system.”

Grant System Leads

Cancer Researchers to Play It Safe, NYT, 28.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/28/health/research/28cancer.html

Swine Flu Cases in the U.S.

Pass a Million, Officials Say

June 27, 2009

The New York Times

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr.

Swine flu has infected more than a million Americans, federal health

officials said Friday, and is infecting thousands more every week even though

the annual flu season is well over.

That total of those who have already been infected is “just a ballpark figure,”

said Dr. Anne Schuchat, director of respiratory diseases at the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, adding, “We know we’re not tracking every single

one of them.”

Only a tiny fraction of those million cases have been tested, Dr. Schuchat said.

The estimate is based on testing plus telephone surveys in New York City and

several other locales where the new flu has hit hard.

A survey in New York City, she said, showed that almost 7 percent of those

called had had flu symptoms during just three weeks in May when the flu was

spreading rapidly through schools. If that percentage of the city has had it,

then there have been more than 500,000 cases in the city alone, though most have

been mild enough that doctors recommended nothing more than rest and fluids.

The flu has now spread to many areas of the country, Dr. Schuchat noted, and the

C.D.C. has heard of outbreaks in 34 summer camps in 16 states.

About 3,000 Americans have been hospitalized, she said, and their median age is

quite young, just 19. Of those, 127 have died.

The median age for deaths is somewhat higher, at 37, but that number is pushed

up because while only a few elderly people catch the new flu, about 2 percent of

them die as a result.

Of those who die, Dr. Schuchat said, about three-quarters have some underlying

condition like morbid obesity, pregnancy, asthma, diabetes or immune system

problems. Even those victims, she said, “tend to be relatively young, and I

don’t think that they were thinking of themselves as ready to die.”

The new flu has now reached more than 100 countries, according to the World

Health Organization. The world’s eyes are on the Southern Hemisphere, which is

at the beginning of its winter, when flu spreads more rapidly. Australia, Chile

and Argentina are seeing a fast spread of the virus, mostly among young people,

while one of the usual seasonal flus, an H3N2, is also active.

Five American vaccine companies are working on a swine flu vaccine, Dr. Schuchat

said. The C.D.C. has estimated that once the new vaccine is tested for both

safety and effectiveness, no more than 60 million doses will be available by

September. That means difficult decisions will have to be made about whom to

give it to first.

Swine Flu Cases in the

U.S. Pass a Million, Officials Say,

NYT, 27.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/27/health/27flu.html

Mind

Where Can the Doctor Who’s Guided

All the Others Go for Help?

June 23, 2009

The New York Times

By ELISSA ELY, M.D.

Psychiatry is a relatively safe profession, but it has a hazard that is not

apparent at first glance: if you are in it long enough, there may be no one to

talk to about your own problems.

It is not that way when you start out. Most psychiatric residents spend a good

deal of time in therapy with a senior psychiatrist, for a number of reasons —

not least, that it is the most intimate way to learn technical magic. Books

teach the same thing to everyone who reads them. But no one forgets the

crystalline remark their therapist made just to them, and how they viewed

themselves differently ever after.

At a certain point, though, you stop being the student and become the teacher.

You settle into the details of a career — hospital, research, private practice.

Roots go down, time passes. Eventually, younger psychiatrists begin to approach

you. Now you are the generation above, saving early-morning slots for residents

before they head off to clinic and class. You lower fees and accommodate their

hurtling, insane schedules. You remember how it was.

But no amount of wisdom prevents personal frailty. You are never too old for

your own problems. Yet when you are the professional others go to, where do you

bring your sorrows and secret pain?

Sometimes the situation is clear. During my training there was a formidable

psychiatrist who disappeared periodically. Everyone knew she was being

hospitalized for a recurrent manic psychosis, and that she would be back to

intimidate the trainees as soon as medications had stabilized her.

There was an oddness about it, but no dishonor. Actually, her illness made her

more impressive. We are taught to explain that mental illness has a biological

component responsive to medical treatment, just like diabetes or heart disease.

Her example brought conviction to our tone.

In my residency, I moonlighted in a medication clinic where an elderly

psychiatrist was being treated for a dementia he did not recognize. He could not

remember simple requests, raised his cane to strangers, screamed at family

members; his wife met with me separately and told me she was ready to leave him.

Carefully writing “Dr.” on the top line of each of his prescriptions, I felt

undersized and overregarded. Yet he took the pills without question and showed a

fatherly interest in my career. Years later, I thought maybe his wife had chosen

a student deliberately. My junior status allowed him to maintain his senior

status.

Often, though, the situation is not straightforward, and medication is not the

problem. Life is. Maybe we are overcome, maybe ashamed, maybe despairing.

Self-revelation — the nakedness necessary in therapy — is hard when you have

been a model to others.

“In my situation, it would be difficult to find someone,” Dr. Dan Buie, a

beloved senior analyst in Boston, told me. It is not that psychiatrists aren’t

waiting in wing chairs all over the city. It is that so many of them are former

students and former patients. One generation of psychiatrists grows the next

through teaching and treatment.

Surrendering that professional identity to become a patient reverses a kind of

natural order. “You can’t be a simple patient,” Dr. Buie said. “Anyone I’d go

to, I’ve known.” To avoid it, some travel to other cities for therapy (probably

passing colleagues in trains heading in the other direction).

There is also the factor of experience. It is one thing if my internist is

younger than I; she is closer to the bones of medicine, and with any luck we can

get to know each other for years before serious illness requires more intimate

contact. It is another thing if my therapist is younger than I.

“It would be a big mistake not to turn to someone,” Dr. Buie went on, “but I

might have some trouble going to younger colleagues. It’s hard to understand the

issues that come up in the course of a life cycle unless you’ve lived it

yourself.”

Dr. Rachel Seidel, a psychoanalyst and psychiatrist in Cambridge, said that when

people feel vulnerable, “we want someone with more insight than we have.”

“It’s a paradox,” she added. “Do I have to have gone through what you’ve gone

through in order to be empathic to you? And yet, I’d have a preference for

someone who’s been around longer.”

Some look laterally for help. Peer supervision is a well-known form of risk

management; presenting troubling professional cases to colleagues prevents folly

and mistakes at any age.

“I use a couple of peers,” said Dr. Thomas Gutheil, professor of psychiatry at

Harvard Medical School. “Then they use me. It’s the reciprocity that’s key — you

feel the comfort of telling everything about yourself when you know the reverse

is also true.”

Other solutions are even closer. The playwright Edward Albee once wrote that it

can be necessary to travel a long distance out of the way in order to come back

a short distance correctly. The best source of help can be the nearest source of

all. An elderly luminary at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute

listened without comment when asked: Whom does he — the doctor others seek out

for help — seek out for help himself? He wasted no words.

“My wife,” he said crisply.

Elissa Ely is a psychiatrist in Boston.

Where Can the Doctor

Who’s Guided All the Others Go for Help?, NYT, 23.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/health/23mind.html

Obama Announces

Agreement With Drug Companies

June 22, 2009

Filed at 1:04 p.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

WASHINGTON (AP) -- President Barack Obama on Monday welcomed the

pharmaceutical industry's agreement to help close a gap in Medicare's drug

coverage, calling the pact a step forward in the push for overhaul of the

nation's health care system.

Obama said that drug companies have pledged to spend $80 billion over the next

decade to help reduce the cost of drugs for seniors and pay for a portion of

Obama's health care legislation. The agreement with the pharmaceutical industry

would help close a gap in prescription drug coverage under Medicare.

''This is a significant breakthrough on the road to health care reform, one that

will make a difference in the lives of many older Americans,'' Obama said in the

White House's Diplomatic Room.

He was joined by Sen. Max Baucus, D-Mont., the chairman of the Senate Finance

Committee who struck the deal with the White House; Sen. Chris Dodd, D-Conn.,

and Barry Rand, head of the senior citizens' advocacy group AARP. Notably absent

was a representative from the pharmaceutical association.

''It was always designed to be an AARP event,'' said Ken Johnson, spokesman for

the association. ''We don't think we should have been invited to it.''

Johnson said Billy Tauzin, the group's president and a former Republican

congressman from Louisiana, will attend a town hall meeting on health care that

Obama is staging at the White House on Wednesday.

Johnson said there are other parts to the agreement that have still not been

completed, but he declined to provide details.

''There are a lot of discussions going on right now, there are a lot of moving

pieces, there are a lot of elements to it that have not been finalized,''

Johnson said.

The president used the opportunity to make his sternest call yet for action,

saying the drug agreement is one piece of ''health care reform I expect Congress

to enact this year.''

Obama said the move on Medicare will help correct an anomaly in the program that

provides a prescription drug benefit through the government health care program

for the elderly and disabled. Under the deal, drug companies will pay part of

the cost of brand name drugs for lower and middle-income older people in the

so-called ''doughnut hole.'' That term refers to a feature of the current drug

program that requires beneficiaries to pay the entire cost of prescriptions

after initial coverage is exhausted but before catastrophic coverage begins.

Obama said some Medicare beneficiaries will find at least a 50 percent discount

on prescription drugs. Obama says drug companies stand to benefit when more

Americans can afford prescription drugs.

The drug companies' investment would reduce the cost of drugs for seniors and

pay for a portion of Obama's proposed revamping of health care.

''This is an early win for reform,'' Rand said.

Under the agreement, part of the $80 billion would be used to halve the cost of

brand name drugs for Medicare recipients when they are in a coverage gap of the

program. AARP, which represents 40 million older Americans, has long lobbied to

eliminate that coverage gap completely.

The deal would affect about 26 million low- and middle-income recipients of the

program's enrollees, AARP said. It would apply to brand name and biologic drugs,

but not generics, the group said, and likely take effect in July 2010, assuming

drug overhaul legislation becomes law.

Under Medicare's Part D prescription drug program, recipients pay about 25

percent of the cost of their drugs until they and the government have paid

$2,700.

At that point, beneficiaries must cover the full cost of drugs until they have

spent $4,350 from their own pockets. When they reach that amount, Medicare's

catastrophic drug benefit takes effect, and recipients only pay 5 percent of

their drugs' costs until the end of the year.

--------

Associated Press Writer Alan Fram contributed to this report.

Obama Announces

Agreement With Drug Companies, NYT, 22.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/06/22/us/politics/AP-US-Obama-Drugs.html

Editorial

A Public Health Plan

June 21, 2009

The New York Times

As the debate on health care reform unfolds, no issue has caused such

partisan rancor — and spawned such misleading rhetoric — as whether to create a

new public insurance plan to compete with private plans.

The nation already has several huge public plans, including Medicare for the

elderly (once reviled by conservatives, it is now only short of the flag in its

popularity) and Medicaid for the poor.

Now the issue is whether to establish a new public plan to encourage more

competition among health insurers and provide Americans with an alternative.

Most Democrats and some Republicans have already accepted the need to create one

or more health insurance exchanges where individuals without group coverage and

possibly small businesses could buy insurance policies. Some proponents hope

that big businesses could enroll their workers as well.

An exchange would give the government (federal or state) a lot more power over

insurers that choose to participate in order to tap a vast new market of

previously uninsured people. It would determine the range of benefits that all

participating plans would have to offer. It would presumably require those plans

to accept all applicants, regardless of “pre-existing conditions.”

What Republicans are adamantly opposed to is the idea of adding a public plan to

that exchange. They portray it as a “government takeover” of the health care

system, or even as socialized medicine. Those are egregious

mischaracterizations.

There is no serious consideration in Congress of a single-payer governmental

program that would enroll virtually everyone. Nor is there any talk of extending

the veterans health care system, a stellar example of “socialized medicine,” to

the general public.

The debate is really over whether to open the door a crack for a new public plan

to compete with the private plans. Most Democrats see this as an important

element in any health care reform, and so do we.

A public plan would have lower administrative expenses than private plans, no

need to generate big profits, and stronger bargaining power to obtain discounts

from providers. That should enable it to charge lower premiums than many private

plans.

It would also provide an alternative for individuals who either can’t get

adequate insurance from private insurers or don’t trust the private insurance

industry to treat them fairly. And it could serve as a yardstick for comparing

the performance of private plans and for testing innovative coverage schemes.

Unfortunately, many Senate Democrats are so desperate to find a political

compromise with Republicans — or so bullied by the rhetoric — that they are in

danger of gravely weakening a public plan, or eliminating it entirely. That

would be a mistake.

Here is a look at the main proposals now under consideration:

THE MOST ROBUST This approach, favored by many analysts, would allow the new

public plan to piggy-back on the rate-setting powers of Medicare. As a result,

it is the one most feared by Republicans, the insurance industry and doctors and

hospitals. Any doctors who wanted to participate in Medicare, as virtually all

do, would also have to participate in this plan and would have to accept the

same payment rates as Medicare provides.

With lower costs, it would be cheaper for consumers, charging its members

premiums as much as 20 to 30 percent lower than premiums for comparable private

coverage, a boon to hard-pressed families.

It would also shave hundreds of billions of dollars from the amount needed to

cover the uninsured — a crucial advantage as Congress scrambles to finance the

reform effort.

The risk is that if this plan, given its power, were too stingy, it might drive

some financially stressed hospitals into bankruptcy. The hope is that the

downward pressure on reimbursements might force them to innovate and find big

savings.

Republicans and private insurers fear, with some reason, that such an

inexpensive public plan would entice or drive tens of millions of Americans away

from private insurance, especially if big employers were allowed to enroll their

workers in an exchange. The challenge is to craft rules to discourage employers

from simply dropping their own subsidies entirely.

The prospect of competing with a government plan terrifies the private insurers.

But in our judgment, if that many Americans were to decide that such a plan is a

better deal for them and their families, that would be a good thing. Innovative

private plans that already deliver better services at lower costs would survive.

Inefficient private plans would wither.

In an effort to address some of these fears, Senator Jay Rockefeller has

introduced a bill that would use Medicare provider payment rates for only the

first two years and let doctors opt out after three years while remaining in

Medicare. That would get the new public plan off to a good start, after which it

would compete on its own.

LIGHTER VERSIONS Other proposals are circulating that would level the playing

field with private plans. They would require the public plan to hold the same

reserves as private plans and sustain itself from premium income without drawing

on the federal treasury. It would probably pay providers higher rates than

Medicare but lower rates than most private plans. Its administrative costs would

be far lower, allowing it to offer lower premiums. These more modest versions

could be worth having, but they would save individuals and the health care

system far less money.

STATE-BASED PLANS A bipartisan group, led by three former Senate leaders —

Republicans Bob Dole and Howard Baker and Democrat Tom Daschle — has proposed

leaving it to states to create public plans if they wish. The federal government

would be able to step in after five years if a state has failed to establish an

exchange with affordable insurance options. That looks like a formula for delay

and inaction.

COOPERATIVES Propelled by a belief that no public plan could survive a

Republican filibuster, Senator Kent Conrad, Democrat of North Dakota, has

proposed instead setting up private nonprofit cooperatives — run for the benefit

of their members rather than stockholders — to compete with profit making

insurance plans.

The presumed advantage of this approach is that cooperatives might be able to

charge lower premiums because they would not have to earn large profits. Their

performance, too, would be a yardstick against which to measure whether profit

making plans are charging fair premiums.

Health care cooperatives have existed at the local or regional level for decades

in this country. Many have gone belly up. A few still provide high quality care

at reasonable prices. Given sufficient size, seed money and negotiating power, a

cooperative organization could help transform the health care system. But

Republicans seem unlikely to accept a strong national organization, so creation

of cooperatives is apt to be local and spotty. They would be unlikely to deliver

as much savings as a large public plan.

TIGHT REGULATION Right from the start of the debate, some experts have suggested

that much tighter regulation of the new insurance exchange could achieve many of

the goals of a public plan.

Regulators could insist that insurers not exclude people with pre-existing

conditions or charge them higher premiums. The exchange could offer customers a

menu of private plans and be modeled on the federal program that serves Congress

and other government personnel. Several European countries, including Germany,

provide better health care at lower cost than the United States without relying

on a public plan. And the near-universal coverage in Massachusetts was achieved

without a public plan option.

We continue to believe that a public plan would be desirable. Surveys by the

Commonwealth Fund have found that Medicare beneficiaries report fewer problems

obtaining medical care, less financial hardship due to medical bills, and higher

satisfaction with their coverage than do workers insured by private employers.

If Senate Republicans block a public plan, much tighter regulation will be

essential to guarantee affordable private coverage for millions of Americans.

A Public Health Plan,

NYT, 21.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/21/opinion/21sun1.html

House Unveils Health Bill,

Minus Key Details

June 20, 2009

The New York Times

By ROBERT PEAR

and DAVID M. HERSZENHORN

WASHINGTON — House Democrats on Friday answered President Obama’s call for a

sweeping overhaul of the health care system, unveiling a bill that they said

would cover 95 percent of Americans. But they said they did not know how much it

would cost and had not decided how to pay for it.

The proposal would establish a new public health insurance plan to compete with

private plans. Republicans and insurance companies strenuously oppose such an

entity, saying it could lead to a government takeover of health care. The draft

bill would require all Americans to carry health insurance. Most employers would

have to provide coverage to employees or pay a fee equivalent to 8 percent of

their payroll. The plan would also end many insurance company practices that

deny coverage or charge higher premiums to sick people.

“Health insurance for most American families is just one big surprise,” said

Representative George Miller of California, the chairman of the Education and

Labor Committee. “When you go to use it, you find out it’s not quite as it’s

represented, and you spend hours on the phone with exclusions and discussions

and referrals to other legal documents that you didn’t have at the time you

purchased it.”

The 852-page House bill, as expected, is more expansive than the legislation

taking shape in the Senate, where work on the issue bogged down this week after

early cost estimates came in far higher than expected. The initial price tag for

a measure drafted by the Senate Finance Committee, for example, was $1.6

trillion over 10 years.

Similar sticker shock could hit House members when they see the cost of their

bill, which incorporates many ideas from health policy experts about how to fix

the health system.

Industry critics of the emerging Senate bill are likely to have even more

objections to the House version, but House Democratic leaders can probably push

their measure through on a party-line vote.

Under the House bill, health insurance would be regulated by a powerful new

federal agency, headed by a presidential appointee known as the health choices

commissioner.

The draft bill was unveiled by three committee chairmen — Mr. Miller; Henry A.

Waxman of California, chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee; and Charles

B. Rangel of New York, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. The chairmen,

all first elected in the 1970s, have worked together in secret for months to

develop a single bill.

The proposal would expand Medicaid eligibility, increase Medicaid payments to

primary care doctors and gradually close a gap in Medicare coverage of

prescription drugs known as a doughnut hole. The bill would also reverse deep

cuts in Medicare payments to doctors scheduled to occur in the next five years.

Taken together, these provisions could significantly drive up the bill’s cost.

The bill would impose a new “tax on individuals without acceptable health care

coverage.” The tax would be based on a person’s income and could not exceed the

average cost of a basic health insurance policy. People could be exempted from

the tax “in cases of hardship.”

Asked why there was no cost estimate for the bill, the House Democratic leader,

Steny H. Hoyer of Maryland, said: “Until we have a final product, we are

reluctant to ask the Congressional Budget Office for a score. But whatever we do

will be fully paid for.”

House Democrats pledged to offset the cost of their legislation by reducing the

growth of Medicare and imposing new, unspecified taxes.

Republicans, who had no role in developing the bill, denounced it as a blueprint

for a vast increase in federal power and spending.

“Families and small businesses who are already footing the bill for Washington’s

reckless spending binge will not support it,” said the House Republican leader,

John A. Boehner of Ohio, who raised the specter of federal bureaucrats’ making

medical decisions for millions of people.

Business groups also were not pleased. “There is enough to see here already to

know that we would be compelled to oppose this bill,” said E. Neil Trautwein, a

vice president of the National Retail Federation.

But John J. Sweeney, president of the A.F.L.-C.I.O., praised the House bill,

saying it provided “a road map for what health care reform should look like.”

The House chairmen described their bill as a starting point in a battle that

would dominate Congress this summer and ultimately involve the full range of

interest groups in Washington. The three House committees plan to hold as many

as six hearings on the bill next week. Mr. Waxman said lawmakers were committed

to considering all ideas, even a proposal to tax some employer-provided health

benefits, which he opposes.

The House bill shows what Democrats mean when they speak of a “robust” public

insurance plan.

Under the bill, the public plan would be run by the Department of Health and

Human Services and would offer three or four policies, with different levels of

benefits. The plan would initially use Medicare fee schedules, paying most

doctors and hospitals at Medicare rates, plus about 5 percent. After three

years, the health secretary could negotiate with doctors and hospitals.

But the bill says, “There shall be no administrative or judicial review of a

payment rate or methodology” used to pay health care providers in the public

plan.

Scott P. Serota, president of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, said,

“A government-run plan that pays based on Medicare rates, for any period of

time, is a recipe for disaster.”

The bill would limit what doctors could charge patients in the public insurance

plan, just as Medicare limits what doctors can charge beneficiaries.

In setting payment rates for doctors and hospitals under the public plan, the

bill says, the government should try to reduce racial and ethnic disparities and

“geographic variation in the provision of health services.”

The public plan would receive an unspecified amount of start-up money from the

federal government. After that, it would have to be self-sustaining.

The bill would require drug companies to finance improvements in the Medicare

drug benefit. Drug companies would have to pay rebates to the government on

drugs dispensed to low-income Medicare beneficiaries.

The bill would expand Medicaid to cover millions of people with incomes below

133 percent of the poverty level ($14,400 for an individual, $29,330 for a

family of four). The cost would be borne by the federal government.

The government would also offer subsidies to make insurance more affordable for

people with incomes from 133 percent to 400 percent of the poverty level

($43,300 for an individual, $88,200 for a family of four).

House Unveils Health

Bill, Minus Key Details, NYT, 20.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/20/health/policy/20health.html?hpw

Letters

The Rationing of U.S. Medical Care

June 19, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

David Leonhardt (“Limits

in a System That’s Sick,” Economic Scene, June 17) makes no mention of the

most egregious form of medical care rationing — the decisions by insurance

companies to pay or not to pay for medical procedures, decisions that are

routinely based on cost rather than on sound medical practice.

Health care reform will get nowhere until the public understands that the

insurance companies are the ones currently making the rationing decisions. The

objection to a government-run plan — that it would compromise the relationship

of doctor and patient — overlooks the fact that the relationship is already

severely compromised by the insurance companies.

Howard Nenner

Whately, Mass., June 17, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Let’s not forget that health care is also already rationed by socioeconomic

status: the very poor are covered by government plans, and the very rich can

afford whatever treatment they want. It’s we folks in the middle who are left

holding the bag.

Ted Claire

Berkeley, Calif., June 17, 2009

•

To the Editor:

David Leonhardt is correct that health care in the United States is rationed.

Our present system reflects a flawed value system of society that does not

recognize the value of the time, judgment and advice of a fully trained

primary-care physician. Payment is for actions taken. This is different from the

other learned professions.

Thoughtful, conscientious evaluation and management require more time and fewer

actions than third parties pay for. This changes good primary-care doctors into

referral centers to specialists. Paying for time and not just actions is a

prerequisite for meaningful reform.

The cultural desire to know what is wrong immediately is another cause of higher

costs. Immediacy requires myriad tests and imaging done quickly. Careful

observation for a time can be just as effective, safer and less costly. Another

prerequisite for lowering costs is for our national culture to develop some

patience.

Marcus M. Reidenberg

New York, June 17, 2009

The writer, a medical doctor, is a professor of pharmacology, medicine and

public health at Weill Cornell Medical College.

•

To the Editor:

“Doctors and the Cost of Care” (editorial, June 14) unfairly blames “profligate

physician behavior” for high medical spending in the United States. Contrary to

what the Dartmouth researchers claimed, regions with high Medicare per capita

spending are not necessarily wasting money.

Medicare spending per capita is an inaccurate proxy for overall medical

spending. Atul Gawande, in his New Yorker article cited in the editorial, relies

on the Dartmouth Medicare data to identify McAllen, Tex., as the town with the

highest per capita medical spending next to Miami.

But there are reasons other than physician behavior that explain Medicare costs

in McAllen. It is a border town and cares for many newcomers who are uninsured

and can’t pay. Therefore costs are shifted to insurance programs like Medicare.

In addition, to the extent actual medical spending per capita is high in

McAllen, Dr. Gawande points out other reasons. McAllen’s population drinks 60

percent more than average and has a 38 percent obesity rate.

Most doctors put their patients first, and many doctors provide free treatment

when a patient cannot pay. What a shame doctors are being vilified in the name

of reform. Betsy McCaughey

New York, June 15, 2009

The writer is chairwoman of the Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths and a

former lieutenant governor of New York State.

•

To the Editor:

I was disturbed to see your editorial suggest that the blame for “ever rising

premiums” falls primarily on physicians. Let’s give credit where credit is due.

Between 2000 and 2007, the 10 largest publicly traded insurance companies

increased their profits 428 percent, from $2.4 billion to $12.9 billion,

according to Securities and Exchange Commission filings.

During the same period, the number of insurers fell by nearly 20 percent,

largely because of a huge wave of mergers that led to stunning consolidation.

And premiums increased by more than 87 percent, rising four times faster than

the average American’s wages.

Today, 95 percent of American insurance markets qualify as tight oligopolies. As

in so many industries, blind reliance on free-market forces has failed the

American public.

Clearly, doctors bear a responsibility to curb costs. But the real culprits are

the middlemen who, after years of lax regulation, now have such a tight grip on

the market that they can — and do — charge whatever they want.

David A. Balto

Washington, June 14, 2009

The writer is a senior fellow with the Center for American Progress.

•

To the Editor:

Since its founding, Mayo Clinic has paid physicians with salaries to avoid

financial conflicts of interest in clinical decision-making, and to promote

multi-disciplinary coordination of care. Less well known, but important to

Mayo’s early growth, was its principle of billing based on patients’ means.

Using a sliding scale, wealthier patients paid more than poorer patients did for

the same care. Such means adjustment increased patient volumes, which

strengthened Mayo’s expertise and efficiency, benefiting rich and poor alike.

Health reform warrants similar means-adjustment principles. Consumer-owned

cooperatives could buy high-deductible, low-premium insurance policies, and pay

below-deductible bills, using means-adjusted withdrawals from participants’

health savings accounts. Such a plan would improve outcomes and value more

effectively than bureaucratic price-setting would.

Randall C. Walker

Rochester, Minn., June 15, 2009

The writer is a medical doctor at the Division of Infectious Diseases, Mayo

Clinic College of Medicine.

The Rationing of U.S.

Medical Care, NYT, 19.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/19/opinion/l19doctors.html?hpw

Report on Gene for Depression

Is Now Faulted

June 17, 2009

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

One of the most celebrated findings in modern psychiatry — that a single gene

helps determine one’s risk of depression in response to a divorce, a lost job or

another serious reversal — has not held up to scientific scrutiny, researchers

reported Tuesday.

The original finding, published in 2003, created a sensation among scientists

and the public because it offered the first specific, plausible explanation of

why some people bounce back after a stressful life event while others plunge

into lasting despair.

The new report, by several of the most prominent researchers in the field, does

not imply that interactions between genes and life experience are trivial; they

are almost certainly fundamental, experts agree.

But it does suggest that nailing down those factors in a precise way is far more

difficult than scientists believed even a few years ago, and that the original

finding could have been due to chance. The new report is likely to inflame a

debate over the direction of the field itself, which has found that the genetics

of illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder remain elusive.

“This gene/life experience paradigm has been very influential in psychiatry,

both in the studies people have done and the way data has been interpreted,”

said Dr. Kenneth S. Kendler, a professor of psychiatry and human genetics at

Virginia Commonwealth University, “and I think this paper really takes the wind

out of its sails.”

Others said the new analysis was unjustifiably dismissive. “What is needed is

not less research into gene-environment interaction,” Avshalom Caspi, a

neuroscientist at Duke University and lead author of the original paper, wrote

in an e-mail message, “but more research of better quality.”

The original study was so compelling because it explained how nature and nurture

could collude to produce a complex mood problem. It followed 847 people from

birth to age 26 and found that those most likely to sink into depression after a

stressful event — job loss, sexual abuse, bankruptcy — had a particular variant

of a gene involved in the regulation of serotonin, a brain messenger that

affects mood. Those in the study with another variant of the gene were

significantly more resilient.

“I think what happened is that people who’d been working in this field for so

long were desperate to have any solid finding,” Kathleen R. Merikangas, chief of

the genetic epidemiology research branch of the National Institute of Mental

Health and senior author of the new analysis, said in a phone interview. “It was

exciting, and some people thought it was the finding in psychiatry, a major

advance.”

The excitement spread quickly. Newspapers and magazines reported the finding.

Columnists, commentators and op-ed writers emphasized its importance. The study

provided some despairing patients with comfort, and an excuse — “Well, it is in

my genes.” It reassured some doctors that they were medicating an organic

disorder, and stirred interest in genetic testing for depression risk.

Since then, researchers have tried to replicate the gene finding in more than a

dozen studies. Some found similar results; others did not. In the new study,

being published Wednesday in The Journal of the American Medical Association,

Neil Risch of the University of California, San Francisco, and Dr. Merikangas

led a coalition of researchers who identified 14 studies that gathered the same

kinds of data as the original study. The authors reanalyzed the data and found

“no evidence of an association between the serotonin gene and the risk of

depression,” no matter what people’s life experience was, Dr. Merikangas said.

By contrast, she said, a major stressful event, like divorce, in itself raised

the risk of depression by 40 percent.

The authors conclude that the widespread acceptance of the original findings was

premature, writing that “it is critical that health practitioners and scientists

in other disciplines recognize the importance of replication of such findings

before they can serve as valid indicators of disease risk” or otherwise change

practice.

Dr. Caspi and other psychiatric researchers said it would be equally premature

to abandon research into gene-environment interaction, when brain imaging and

other kinds of evidence have linked the serotonin gene to stress sensitivity.

“This is an excellent review paper, no one is questioning that,” said Myrna

Weissman, a professor of epidemiology and psychiatry at Columbia. “But it

ignored extensive evidence from humans and animals linking excessive sensitivity

to stress” to the serotonin gene.

Dr. Merikangas said she and her co-authors deliberately confined themselves to

studies that could be directly compared to the original. “We were looking for

replication,” she said.

Report on Gene for

Depression Is Now Faulted, NYT, 17.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/17/science/17depress.html?hp

Economic Scene

Health Care Rationing Rhetoric

Overlooks Reality

June 17, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID LEONHARDT

Rationing.

More to the point: Rationing!

As in: Wait, are you talking about rationing medical care? Access to medical

care is a fundamental right. And rationing sounds like something out of the

Soviet Union. Or at least Canada.

The r-word has become a rejoinder to anyone who says that this country must

reduce its runaway health spending, especially anyone who favors cutting back on

treatments that don’t have scientific evidence behind them. You can expect to

hear a lot more about rationing as health care becomes the dominant issue in

Washington this summer.

Today, I want to try to explain why the case against rationing isn’t really a

substantive argument. It’s a clever set of buzzwords that tries to hide the fact

that societies must make choices.

In truth, rationing is an inescapable part of economic life. It is the process

of allocating scarce resources. Even in the United States, the richest society

in human history, we are constantly rationing. We ration spots in good public

high schools. We ration lakefront homes. We ration the best cuts of steak and

wild-caught salmon.

Health care, I realize, seems as if it should be different. But it isn’t.

Already, we cannot afford every form of medical care that we might like. So we

ration.

We spend billions of dollars on operations, tests and drugs that haven’t been

proved to make people healthier. Yet we have not spent the money to install

computerized medical records — and we suffer more medical errors than many other

countries.

We underpay primary care doctors, relative to specialists, and they keep us

stewing in waiting rooms while they try to see as many patients as possible. We

don’t reimburse different specialists for time spent collaborating with one

another, and many hard-to-diagnose conditions go untreated. We don’t pay nurses

to counsel people on how to improve their diets or remember to take their pills,

and manageable cases of diabetes and heart disease become fatal.

“Just because there isn’t some government agency specifically telling you which

treatments you can have based on cost-effectiveness,” as Dr. Mark McClellan,

head of Medicare in the Bush administration, says, “that doesn’t mean you aren’t

getting some treatments.”

Milton Friedman’s beloved line is a good way to frame the issue: There is no

such thing as a free lunch. The choice isn’t between rationing and not

rationing. It’s between rationing well and rationing badly. Given that the

United States devotes far more of its economy to health care than other rich

countries, and gets worse results by many measures, it’s hard to argue that we

are now rationing very rationally.

On Wednesday, a bipartisan panel led by four former Senate majority leaders —

Howard Baker, Tom Daschle, Bob Dole and George Mitchell — will release a solid

proposal for health care reform. Among other things, it would call on the

federal government to do more research on which treatments actually work. An

“independent health care council” would also be established, charged with

helping the government avoid unnecessary health costs. The Obama administration

supports a similar approach.

And connecting the dots is easy enough. Armed with better information, Medicare

could pay more for effective treatments — and no longer pay quite so much for

health care that doesn’t make people healthier.

Mr. Baker, Mr. Daschle, Mr. Dole and Mr. Mitchell: I accuse you of rationing.

•

There are three main ways that the health care system already imposes rationing

on us. The first is the most counterintuitive, because it doesn’t involve

denying medical care. It involves denying just about everything else.

The rapid rise in medical costs has put many employers in a tough spot. They

have had to pay much higher insurance premiums, which have increased their labor

costs. To make up for these increases, many have given meager pay raises.

This tradeoff is often explicit during contract negotiations between a company

and a labor union. For nonunionized workers, the tradeoff tends to be invisible.

It happens behind closed doors in the human resources department. But it still

happens.

Research by Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra of Harvard has found that, on

average, a 10 percent increase in health premiums leads to a 2.3 percent decline

in inflation-adjusted pay. Victor Fuchs, a Stanford economist, and Ezekiel

Emanuel, an oncologist now in the Obama administration, published an article in

The Journal of the American Medical Association last year that nicely captured

the tradeoff. When health costs have grown fastest over the last two decades,

they wrote, wages have grown slowest, and vice versa.

So when middle-class families complain about being stretched thin, they’re

really complaining about rationing. Our expensive, inefficient health care

system is eating up money that could otherwise pay for a mortgage, a car, a

vacation or college tuition.

The second kind of rationing involves the uninsured. The high cost of care means

that some employers can’t afford to offer health insurance and still pay a

competitive wage. Those high costs mean that individuals can’t buy insurance on

their own.

The uninsured still receive some health care, obviously. But they get less care,

and worse care, than they need. The Institute of Medicine has estimated that

18,000 people died in 2000 because they lacked insurance. By 2006, the number

had risen to 22,000, according to the Urban Institute.

The final form of rationing is the one I described near the beginning of this

column: the failure to provide certain types of care, even to people with health

insurance. Doctors are generally not paid to do the blocking and tackling of

medicine: collaboration, probing conversations with patients, small steps that

avoid medical errors. Many doctors still do such things, out of professional

pride. But the full medical system doesn’t do nearly enough.

That’s rationing — and it has real consequences.

In Australia, 81 percent of primary care doctors have set up a way for their

patients to get after-hours care, according to the Commonwealth Fund. In the

United States, only 40 percent have. Over all, the survival rates for many

diseases in this country are no better than they are in countries that spend far

less on health care. People here are less likely to have long-term survival

after colorectal cancer, childhood leukemia or a kidney transplant than they are

in Canada — that bastion of rationing.

None of this means that reducing health costs will be easy. The

comparative-effectiveness research favored by the former Senate majority leaders

and the White House has inspired opposition from some doctors, members of

Congress and patient groups. Certainly, the critics are right to demand that the

research be done carefully. It should examine different forms of a disease and,

ideally, various subpopulations who have the disease. Just as important,

scientists — not political appointees or Congress — should be in charge of the

research.

But flat-out opposition to comparative effectiveness is, in the end, opposition

to making good choices. And all the noise about rationing is not really a

courageous stand against less medical care. It’s a utopian stand against better

medical care.

Health Care Rationing

Rhetoric Overlooks Reality, NYT, 17.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/17/business/economy/17leonhardt.html?hp

Cost Concerns

as Obama Pushes Health Issue

June 16, 2009

The New York Times

By ROBERT PEAR

and JACKIE CALMES

WASHINGTON — President Obama went before a convention of receptive but wary

doctors on Monday to make the economic case for a health care overhaul, both for

the nation and for the physicians’ own bottom lines.

But as the president spoke at the annual conference of the American Medical

Association in Chicago, it became clear that one of the major health plans on

the table would cost at least $1 trillion over 10 years yet leave tens of

millions of people uninsured.

Congress is wrestling with how to pay for Mr. Obama’s vision to extend health

care to all Americans, and some lawmakers are considering tax increases and

spending cuts different from the ones he has proposed. House Democrats, for

example, are weighing a tax on soft drinks and a value-added tax, a broad-based

consumption tax similar to the sales taxes many states levy.

An analysis released Monday by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office

raised the hurdles for draft legislation in the Senate just as its Health,

Education, Labor and Pensions Committee planned to begin voting on Wednesday.

The office concluded that a plan by the committee’s Democratic leaders, Senators

Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts and Christopher J. Dodd of Connecticut, would

reduce the number of uninsured only by a net 16 million people. Even if the bill

became law, the budget office said, 36 million people would remain uninsured in

2017.

That finding came as a surprise. Robert D. Reischauer, an economist who headed

the budget office when Congress tackled the health care issue in the Clinton

administration, said that if so many people remained uninsured, it might not be

feasible to cut special federal payments to hospitals that serve many low-income

people.

Mr. Obama said Saturday that the government could save $106 billion over 10

years by cutting such hospital payments as more people gained coverage.

Senator Orrin G. Hatch of Utah, a senior Republican on both committees drafting

health legislation, said he found the office’s numbers stunning. He calculated

that the Kennedy bill would cost taxpayers $62,500 per uninsured person over the

10 years.

Mr. Obama took the cost issue head on in Chicago. “The cost of inaction is

greater,” he told the doctors, because rising health care prices are “an

escalating burden on our families and businesses” and “a ticking time bomb for

the federal budget.”

Opening a week in which health care will dominate attention in Congress, the

president’s speech on Monday was the latest example of an oft-used ploy to press

his case: appearing before skeptical audiences, confident of his powers of

persuasion but willing as well to say what his listeners do not want to hear.

Mr. Obama spoke just days after the A.M.A. had signaled opposition to his

proposal for a public health insurance plan to compete with private insurers as

part of a menu of choices, much like the one for members of Congress.

“The public option is not your enemy,” Mr. Obama said. “It is your friend, I

believe.” Saying it would “keep the insurance companies honest,” the president

dismissed as “illegitimate” the claims of critics that a public insurance option

amounts to “a Trojan horse for a single-payer system” run by the government.

Mr. Obama twice referred to the use of such “fear tactics” about “socialized

medicine” in past legislative battles, without pointing out that the A.M.A., a

traditionally Republican-leaning group, was among those using the charge, as in

the mid-1960s debate over creating Medicare for people 65 and older.

Mr. Obama drew repeated applause, and even some standing ovations, when he

called for incentives to get more medical students to go into primary care

instead of the more lucrative specialty practices, and when he pledged to work

with doctors to reduce their often unnecessary “defensive medicine” to avoid

malpractice lawsuits. But scattered boos met his follow-up remark that he

opposed any cap on malpractice awards.

The president’s emphasis on reducing health care costs over expanding insurance

coverage, which dates to his campaign, reverses Democrats’ priorities of recent

years. Obama advisers say the focus on cost savings has appeal for all

Americans, not just the uninsured. Some advisers, including veterans of the

Clinton administration, say President Bill Clinton’s emphasis on covering the

uninsured helped doom his health care plan in 1994.

“We have made cost control a coequal objective, just as important as the

expansion of insurance coverage, which has traditionally been the dominant goal

for Democrats,” said Rahm Emanuel, the White House chief of staff. “The entire

discussion has to be centered on controlling or reducing costs.”

That rationale has been Mr. Obama’s answer to those who, after his election,

predicted that he would have to shelve his campaign promise to overhaul health

care to attend instead to an economy in crisis. “If we fail to act, premiums

will climb higher, benefits will erode further, the rolls of the uninsured will

swell to include millions more Americans, all of which will affect your

practice,” he told the A.M.A. members.

The practical problem for Mr. Obama is that by all accounts, the savings and

efficiencies he envisions will not occur quickly, certainly not in the 10-year

time frame of budget scorekeeping for purposes of passing legislation.

The budget office estimated that 39 million people would get coverage through

new “insurance exchanges.” But at the same time, it said, the number of people

with employer-provided health insurance would decline by 15 million, or about 10

percent, and coverage from other sources would fall by 8 million.

In effect, the office said, millions of people would get a better deal if they

bought insurance through an exchange because they could qualify for federal

subsidies not available if they stayed in their employers’ health plans.

Subsidies are expected to average $5,000 to $6,000 a person.

Mr. Obama assured skeptics in the audience: “You did not enter this profession

to be bean counters and paper pushers. You entered this profession to be

healers. And that’s what our health care system should let you be.”

On Wednesday, leaders of the Senate Finance Committee hope to unveil what will

be the one bipartisan measure in Congress.

Democrats on three House panels continue to meet privately to seek consensus on

a single plan. Democrats on the House Ways and Means Committee said they were

trying to decide whether to finance coverage of the uninsured with one

broad-based tax, like the value-added tax, or a combination of smaller taxes.

The value-added tax, common in other countries, is collected in stages from each

business that contributes to the production and sale of consumer goods.

Economists say a 5 percent VAT could have raised $285 billion last year.

But a VAT could violate Mr. Obama’s campaign pledge not to raise taxes on

households with incomes under $250,000 a year.

Cost Concerns as Obama

Pushes Health Issue, NYT, 16.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/16/health/policy/16obama.html

Many in Congress

Hold Stakes in Health Industry

June 14, 2009

The New York Times

By JACKIE CALMES

WASHINGTON — As President Obama and Congress intensify the push to overhaul

health care in the coming week, the political and economic force of that

industry is well represented in the financial holdings of many lawmakers and

others with a say on the legislation, according to new disclosure forms.

The personal financial reports, due late last week from members of Congress,

show that many lawmakers hold investments in insurance, pharmaceutical and

prescription-benefit companies and in hospital interests, all of which would be

affected by the administration’s overhaul of health care.

The lawmakers’ stakes are impossible to quantify because the reports ask for

ranges of value for each asset, and because many officials’ holdings are in

stock index and mutual funds. The Senate majority leader, Harry Reid of Nevada,

for example, has interests in a stock index fund for the health care sector of

more than $50,000 and up to $100,000.

Representative Dave Camp of Michigan, the senior Republican on the Ways and

Means Committee, one of three panels in the House with jurisdiction over health

care, reported at least tens of thousands of dollars in health-related

interests, including the medical technology giant Medtronic, the drug maker

Wyeth and the insurance company Aetna.

In Congress, as members and aides of the three House committees continue to meet

privately, the Senate health committee will begin publicly drafting and voting

on its bill as soon as Tuesday. Later in the week, the Democratic chairman and

senior Republican of the Senate Finance Committee, Max Baucus of Montana and

Charles E. Grassley of Iowa, are expected to unveil a bipartisan plan.

Neither Mr. Baucus, from a ranching family, nor Mr. Grassley, a farmer, have

major health-related holdings, their reports show.

Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, chairman of the health committee,

has much of his wealth in blind trusts.

Senator Christopher J. Dodd, Democrat of Connecticut, leads the health committee

in consultation with Mr. Kennedy. Mr. Dodd’s wife, Jackie Clegg Dodd, is a

member of the board and a shareholder in several health-related companies,

including Cardiome Pharma, Javelin Pharmaceuticals and Brookdale Senior Living.

Senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, a Republican on the health committee, is an

obstetrician with income from his clinic in Muskogee. The wife of Representative

Wally Herger of California, the senior Republican on the health subcommittee of

the Ways and Means panel, works for Catholic Healthcare West, while the wife of

Representative Joe L. Barton of Texas, the top Republican on the House Energy

and Commerce Committee, works for JPS Health Network.

Mr. Obama’s chief adviser on health care, Nancy-Ann DeParle, also filed

disclosure forms with the White House. Ms. DeParle, who served in the Clinton

administration, went on to lucrative positions on the boards of health companies

and as director of a private-equity firm with health investments, earning more

than $2 million from 2008 to this year, according to forms signed on May 13.

The companies included Medco Health Solutions, a pharmacy benefits manager;

Boston Scientific, a device maker; Cerner, a provider of medical information

technology; and DaVita, an operator of dialysis services.

A handwritten note on the forms, dated June 4, says that “all conflicting assets

have been divested.” Ms. DeParle is the wife of a reporter for The New York

Times, Jason DeParle.

Janie Lorber, Ashley Southall and Jack Styczynski contributed reporting.

Many in Congress Hold

Stakes in Health Industry, NYT, 13.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/14/us/politics/14cong.html

Obama Addresses

Paying for Health Care Reforms

June 14, 2009

The New York Times

By SHERYL GAY STOLBERG

and ROBERT PEAR

WASHINGTON — The White House said Saturday that President

Obama intends to pay for his health care overhaul partly by cutting more than

$200 billion in expected reimbursements to hospitals over the next decade — a

proposal that is likely to provoke a backlash from cash-strapped medical

institutions around the country.

Mr. Obama has insisted that his plan will not add to the federal deficit, and he