|

History > 2009 > USA > Justice > Jail, prison (I)

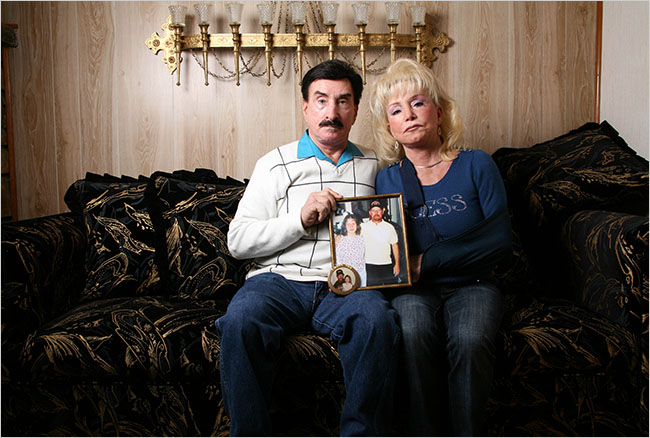

Jack Newbrough and his wife, Heidi,

with a photo of his stepson, Guido,

who died of an untreated infection while in

detention.

Photograph:

Suzanne DeChillo

The New York Times

Another Jail Death, and Mounting Questions

NYT

28.1.2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/28/us/28detain.html

New York

Finds Extreme Crisis

in Youth Prisons

December 14, 2009

The New York Times

By NICHOLAS CONFESSORE

ALBANY — New York’s system of juvenile prisons is broken, with young people

battling mental illness or addiction held alongside violent offenders in abysmal

facilities where they receive little counseling, can be physically abused and

rarely get even a basic education, according to a report by a state panel.

The problems are so acute that the state agency overseeing the prisons has asked

New York’s Family Court judges not to send youths to any of them unless they are

a significant risk to public safety, recommending alternatives, like therapeutic

foster care.

“New York State’s current approach fails the young people who are drawn into the

system, the public whose safety it is intended to protect, and the principles of

good governance that demand effective use of scarce state resources,” said the

confidential draft report, which was obtained by The New York Times.

The report, prepared by a task force appointed by Gov. David A. Paterson and led

by Jeremy Travis, president of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, comes

three months after a federal investigation found that excessive force was

routinely used at four prisons, resulting in injuries as severe as broken bones

and shattered teeth.

The situation was so serious the Department of Justice, which made the

investigation, threatened to take over the system.

But according to the task force, the problems uncovered at the four prisons are

endemic to the entire system, which houses about 900 young people at 28

facilities around the state.

While some prisons for violent and dangerous offenders should be preserved, the

report calls for most to be replaced with a system of smaller centers closer to

the communities where most of the families of the youths in custody live.

The task force was convened in 2008 after years of complaints about the prisons,

punctuated by the death in 2006 of an emotionally disturbed 15-year-old boy at

one center after two workers pinned him to the ground. The task force’s

recommendations are likely to help shape the state’s response to the federal

findings.

“I was not proud of my state when I saw some of these facilities,” Mr. Travis

said in an interview on Friday. “New York is no longer the leader it once was in

the juvenile justice field.”

New York’s juvenile prisons are both extremely expensive and extraordinarily

ineffective, according to the report, which will be given to Mr. Paterson on

Monday. The state spends roughly $210,000 per youth annually, but three-quarters

of those released from detention are arrested again within three years. And

though the median age of those admitted to juvenile facilities is almost 16,

one-third of those held read at a third-grade level.

The prisons are meant to house youths considered dangerous to themselves or

others, but there is no standardized statewide system for assessing such risks,

the report found.

In 2007, more than half of the youths who entered detention centers were sent

there for the equivalent of misdemeanor offenses, in many cases theft, drug

possession or even truancy. More than 80 percent were black or Latino, even

though blacks and Latinos make up less than half the state’s total youth

population — a racial disparity that has never been explained, the report said.

Many of those detained have addictions or psychological illnesses for which less

restrictive treatment programs were not available. Three-quarters of children

entering the juvenile justice system have drug or alcohol problems, more than

half have had a diagnosis of mental health problems and one-third have

developmental disabilities.

Yet there are only 55 psychologists and clinical social workers assigned to the

prisons, according to the task force. And none of the facilities employ

psychiatrists, who have the authority to prescribe the drugs many mentally ill

teenagers require.

While 76 percent of youths in custody are from the New York City area, nearly

all the prisons are upstate, and the youths’ relatives, many of them poor,

cannot afford frequent visits, cutting them off from support networks.

“These institutions are often sorely underresourced, and some fail to keep their

young people safe and secure, let alone meet their myriad service and treatment

needs,” according to the report, which was based on interviews with workers and

youths in custody, visits to prisons and advice from experts. “In some

facilities, youth are subjected to shocking violence and abuse.”

Even before the task force’s report is released, the Paterson administration is

moving to reduce the number of youths held in juvenile prisons.

Gladys Carrión, the commissioner of the Office of Children and Family Services,

the agency that oversees the juvenile justice system, has recommended that

judges find alternative placements for most young offenders, according to an

internal memorandum issued Oct. 28 by the state’s deputy chief administrative

judge.

Ms. Carrión also advised court officials that New York would not contest the

Justice Department findings, according to the memo, and that officials were

negotiating a settlement agreement to remedy the system.

Peter E. Kauffmann, a spokesman for Mr. Paterson, said the governor “looks

forward to receiving the recommendations of the task force as we continue our

efforts to transform the state’s juvenile justice system from a

correctional-punitive model to a therapeutic model.”

The report contends that smaller facilities would place less strain on workers,

helping reduce the use of physical force, and would be better able to tailor

rehabilitation programs.

New York is not unique in using its juvenile prisons to house mentally ill

teenagers, particularly as many states confront huge budget shortfalls that have

resulted in significant cuts to mental health programs. Still, some states are

trying to shift to smaller, community-based programs.

The report by New York’s task force does not say how much money would be needed

to overhaul the system, but as Mr. Paterson and state lawmakers try to close a

$3.2 billion deficit, cost could become a major hurdle.

Ms. Carrión has faced resistance from some prison workers, who accuse her of

making them scapegoats for the system’s problems and minimizing the dangerous

conditions they face. State records show a significant spike in on-the-job

injuries, for which some workers blame Ms. Carrión’s efforts to limit the use of

force.

“We embrace the idea of moving towards a more therapeutic model of care, but you

can’t do that without more training and more staff,” said Stephen A. Madarasz, a

spokesman for the Civil Service Employees Association, the union that represents

prison workers. “You’re not dealing with wayward youth. In the more secure

facilities, you’re dealing with individuals who have been involved in pretty

serious crimes.”

Advocates have credited Ms. Carrión, who was appointed in 2007 by former Gov.

Eliot Spitzer, with instituting significant reforms, including installing

cameras in some of the more troubled prisons and providing more counseling.

But the state has a long way to go, many advocates say.

“Even the kids that are not considered dangerous are shackled when they are

being transferred from their homes to the centers upstate — hands and feet,

sometimes even belly chains,” said Clara Hemphill, a researcher and author of a

report on the state’s youth prisons published in October by the Center for New

York City Affairs at the New School.

“It really is barbaric,” she added, “the way they treat these kids.”

New York Finds Extreme

Crisis in Youth Prisons, NYT, 13.12.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/14/nyregion/14juvenile.html

Arizona May Put State Prisons in Private Hands

October 24, 2009

The New York Times

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER

FLORENCE, Ariz. — One of the newest residents on Arizona’s death row, a

convicted serial killer named Dale Hausner, poked his head up from his

television to look at several visitors strolling by, each of whom wore face

masks and vests to protect against the sharp homemade objects that often are

propelled from the cells of the condemned.

It is a dangerous place to patrol, and Arizona spends $4.7 million each year to

house inmates like Mr. Hausner in a super-maximum-security prison. But in a

first in the criminal justice world, the state’s death row inmates could become

the responsibility of a private company.

State officials will soon seek bids from private companies for 9 of the state’s

10 prison complexes that house roughly 40,000 inmates, including the 127 here on

death row. It is the first effort by a state to put its entire prison system

under private control.

The privatization effort, both in its breadth and its financial goals,

demonstrates what states around the country — broke, desperate and often

overburdened with prisoners and their associated costs — are willing to do to

balance the books. Arizona officials hope the effort will put a $100 million

dent in the state’s roughly $2 billion budget shortfall.

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” said State Representative Andy Biggs, a Republican

who supports private prisons. “If we were not in this economic environment, I

don’t think we’d be talking about this with the same sense of urgency.”

Private prison companies generally build facilities for a state, then charge

them per prisoner to run them. But under the Arizona legislation, a vendor would

pay $100 million up front to operate one or more prison complexes. Assuming the

company could operate the prisons more cheaply or efficiently than the state,

any savings would be equally divided between the state and the private firm.

The privatization move has raised questions — including among some people who

work for private prison companies — about the private sector’s ability to handle

the state’s most hardened criminals. While executions would still be performed

by the state, officials said, the Department of Corrections would relinquish all

other day-to-day operations to the private operator and pay a per-diem fee for

each prisoner.

“I would not want to be the warden of death row,” said Todd Thomas, the warden

of a prison in Eloy, Ariz., run by the Corrections Corporation of America. The

company, the country’s largest private prison operator, has six prisons in

Arizona with inmates from other states.

“That’s not to say we couldn’t,” Mr. Thomas said. “But the liability is too

great. I don’t think any private entity would ever want to do that.”

James Austin, a co-author of a Department of Justice study in 2001 on prison

privatization and president of the JFA Institute, a corrections consulting firm,

said private companies tended to oversee minimum- and medium-security inmates

and had little experience with the most dangerous prisoners.

“As for death row,” Mr. Austin said, “it is a very visible entity, and if

something bad happens there, you will have a pretty big news story for the

Legislature and governor to explain.”

Arizona is no stranger to private prisons or, for that matter, aggressive

privatization efforts (recently, the state put up for sale several government

buildings housing executive branch offices in Phoenix). Nearly 30 percent of the

state’s prisoners are being held in prisons operated by private companies

outside the state’s 10 complexes.

In addition, other states, including Alaska and Hawaii, have contracts with

private companies like Corrections Corporation of America to house their

prisoners in Arizona.

For advocates of prison privatization, the push here breathes a bit of life into

a movement that has been on the decline across the country as cost savings from

prison privatizations have often failed to materialize, corrections officers

unions have resisted the efforts and high-profile problems in privately run

facilities have drawn unwanted publicity

“We have private prisons in Arizona already, and we are very happy with the

performance and the savings we get from them,” said Representative John

Kavanagh, a Republican who is chairman of the House Appropriations Committee and

an architect of the new legislation authorizing the privatization. “I think that

they are the future of corrections in Arizona.”

Under the legislation, any bidder would have to take an entire complex — many of

them mazes of multiple levels of security risks and complexity — and would not

be permitted to pick off the cheapest or easiest buildings and inmates. The

state also wants to privatize prisoners’ medical care.

Louise Grant, a spokeswoman for Corrections Corporation of America, said the

high-security prisoners would be well within the company’s management

capabilities. “We expect we will be there to make a proposal to the state” for

at least some of its complexes up for bid, Ms. Grant said.

In pure financial terms, it is not clear how well the state would make out with

the privatization. The 2001 study for the Department of Justice found that

private prisons saved most states little money (there has been no equivalent

study since). Indeed, many states, struggling to keep up with the cost of

corrections, have closed prisons when possible, and sought changes in sentencing

to reduce crowding in the last two years.

As tough sentencing laws and the ensuing increase in prisoners began to press on

state resources in the 1980s, private prison companies attracted some states

with promises of lower costs. The private prison boom lasted into the 1990s.

Throughout the years, there have been high-profile riots, escapes and other

violent incidents. The companies also do not generally provide the same wages

and benefits as states, which has resulted in resistance from unions and

concerns that the private prisons attract less-qualified workers.

Then the federal government stepped in, with a surge of new immigrant prisoners,

and began to contract with the private companies. The number of federal

prisoners in private prisons in the United States has more than doubled, to

32,712 in 2008 from 15,524 in 2000. The number of state prisoners in privately

run prisons has increased to 93,500 from 75,000 in that time.

With bad economic times again driving many decisions about state resources,

other states are sure to watch Arizona’s experiment closely.

“There simply isn’t the money to keep these people incarcerated, and the

alternative is to free many of them or lower cost,” said Ron Utt, a senior

research fellow for the Heritage Foundation, a conservative group whose work for

privatization was cited by one Arizona lawmaker.

Arizona May Put State

Prisons in Private Hands, NYT, 24.10.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/24/us/24prison.html

Months to Live

Fellow Inmates Ease the Pain of Dying in Jail

October 18, 2009

The New York Times

By JOHN LELAND

COXSACKIE, N.Y. — Allen Jacobs lived hard for his 50 years, and when his

liver finally shut down he faced the kind of death he did not want. On a recent

afternoon Mr. Jacobs lay in a hospital bed staring blankly at the ceiling, his

eyes sunk in his skull, his skin lusterless. A volunteer hospice worker, Wensley

Roberts, ran a wet sponge over Mr. Jacobs’s dry lips, encouraging him to drink.

“Come on, Mr. Jacobs,” he said.

Mr. Roberts is one of a dozen inmates at the Coxsackie Correctional Facility who

volunteer to sit with fellow prisoners in the last six months of their lives.

More than 3,000 prisoners a year die of natural causes in correctional

facilities.

Mr. Roberts recalled a day when Mr. Jacobs, then more coherent, had started

crying. Mr. Roberts held his patient and tried to console him. Then their

experience took a turn unique to their setting, the medical ward of a maximum

security prison. Mr. Roberts said he told Mr. Jacobs to “man up.”

Mr. Jacobs, serving two to four years for passing forged checks, cursed at him,

telling him, “‘I don’t want to die in jail. Do you want to die in jail?’ ”

“I said no,” said Mr. Roberts, who is serving eight years for robbery. “He said,

‘Then stop telling me to man up,’ and he started crying. And then he said that

I’m his family.”

American prisons are home to a growing geriatric population, with one-third of

all inmates expected to be over 50 by next year. As courts have handed down

longer sentences and tightened parole, about 75 prisons have started hospice

programs, half of them using inmate volunteers, according to the National

Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Susan Atkins, a follower of Charles

Manson, died last month in hospice at the Central California Women’s Facility at

Chowchilla after being denied compassionate release.

Joan Smith, deputy superintendent of health services at the Coxsackie prison,

said the hospice program here initially met with resistance from prison guards.

“They were very resentful about people in prison for horrendous crimes getting

better medical care than their families,” including round-the-clock

companionship in their final days, Ms. Smith said.

The guards have come to accept the program, she said. But still there are

challenges unique to the prison setting. Some dying patients, for example,

divert their pain medication to their volunteer aides or other patients, who use

it or sell it, said Kathleen Allan, the director of nursing. She added that

patients can be made victims easily, “and this is a predatory system.”

But she said the inmate volunteers bond with the patients in a way that staff

members cannot, taking on “the touchy-feely thing” that may be inappropriate

between inmates and prison workers.

At Coxsackie, 130 miles north of New York City, administrators started the

hospice program in 1996 in response to the AIDS epidemic using an outside

hospice agency, then changed to inmate volunteers in 2001. The change saved

money and was well-received by the patients.

Perhaps more significant, said William Lape, the superintendent, was the effect

the program had on the volunteers. “I think it’s turned their life around,” Mr.

Lape said.

John Henson, 30, was one of the first volunteers. When he was 18, Mr. Henson

broke into the home of a former employer and, in the course of a robbery, beat

the man to death with a baseball bat. When he entered prison, with a sentence of

25 years to life, he said, “I thought my life was over.”

At Coxsackie he met the Rev. J. Edward Lewis, who persuaded him to volunteer in

2001. “You go in thinking that you’re going to help somebody,” Mr. Lewis said,

“and every time they end up helping you.”

Before hospice, Mr. Henson said he had given little thought to the consequences

of his crime. Then he found himself locked in a hospital room with another

inmate, holding the man’s hand as his breathing slowed toward a stop.

Like many men in prison, the dying man had alienated his family members, who

rejected his efforts to renew contact. In the end, he had only Mr. Henson for

companionship. When the prison nurse declared the man dead, Mr. Henson broke

down in tears.

“They just came out,” he said. “I don’t even know why I was crying. Partly

because of him, partly because of things that died within me at the same time.”

Mr. Henson, dressed in prison greens and with his blond hair buzzed short, spoke

directly and without hesitation.

“I was just thinking about why I’m in here and the person’s life that I took,”

he said. “And sitting with this person for the first time and actually seeing

death firsthand, being right there, my hand in his hand, watching him take his

last breath, just caused me to say, ‘Wow, who the hell are you? Who were you to

do this to somebody else?’ ”

Ms. Allan, the nursing director at Coxsackie, said that with a number of inmate

volunteers, “You can identify in each of these guys something inside them

driving them to do this. It’s a desire to redeem themselves, so even when it

gets hard they’re able to plow through it. “

She added, “I think Mr. Henson made me a better mother.”

Benny Lee, 38, has spent half his life in prison for manslaughter, and for most

of that time, he said, “the only thing I regretted was getting caught.” Four

months ago he began as a hospice volunteer, feeling he needed a change. “I’m

trying to offer some payback,” he said.

On a recent afternoon, Mr. Lee was scheduled to sit with Eddie Jones, 89, who

was dying from multiple causes. Mr. Jones, who was convicted of murder at age

70, said, “I can talk with them better than staff members, because staff members

have their minds made up about how things should be.”

Mr. Lee said he does not know how Mr. Jones’s death will affect him. “I’m hoping

it will have an effect, period,” he said. “Growing up and in prison, I put up

walls. But I have to be more emotionally receptive to these guys. This is going

against everything I’ve tried to do. But I realize it’s a change I have to

make.”

Mr. Lee said hospice was forcing him to learn to trust people.

“It’s helping me mature,” he said. “My views of life and death are changing. I

was unsympathetic when it comes to death. I’ve had friends die, and I was

callous about it. Now I can’t do that. I’ve come to identify with these guys,

not because we’re inmates, but because we’re human beings. What they’re going

through, I’ll go through.”

Fellow Inmates Ease the

Pain of Dying in Jail, NYT, 18.10.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/18/health/18hospice.html

Weighing Prison When the Convict Is Over 80

October 10, 2009

The New York Times

By JOHN ELIGON and BENJAMIN WEISER

In a case involving an 87-year-old man convicted of racketeering, a federal

judge in Manhattan rejected a plea for leniency last year, giving the man a

five-year sentence. The judge in this case had a special perspective: He was 84

himself.

But in another case this spring, an 85-year-old man who admitted providing

sensitive military information to Israel was spared prison by a judge, who cited

the man’s advanced age and said sending him to prison would “serve no purpose.”

In the 12 days they spent deciding the fate of Brooke Astor’s son, Anthony D.

Marshall, the jurors said they did not make much of his age. But now that Mr.

Marshall, who is 85 and had quadruple bypass surgery last year, has been found

guilty of a variety of charges, his age can be expected to have some bearing on

his sentence — though it almost certainly will not serve as a

get-out-of-jail-free card.

Because he was convicted of first-degree grand larceny, which is a felony, Mr.

Marshall faces at least a mandatory sentence of one year behind bars (the most

would be 25 years). But given his age and his physical ailments — he missed

several days of the trial because of his health — and various possible legal

options, it seems reasonable to question how much time Mr. Marshall will spend

as an inmate.

In Mr. Marshall’s case, Justice A. Kirke Bartley Jr. of State Supreme Court in

Manhattan, who is scheduled to sentence Mr. Marshall on Dec. 8, has relatively

little wiggle room to keep Mr. Marshall out of prison because of the state’s

mandatory guidelines.

Mr. Marshall’s grim reality is nothing new; courts are regularly confronted with

the recently convicted who are octogenarians, and who often have ailments

associated with that age.

But judges in New York have not been reluctant to impose real prison time on

elderly defendants, like John J. Rigas, 80, who received a 15-year sentence,

later reduced to 12, for his part in the Adelphia fraud case.

“Here’s why age should be considered,” said Gerald L. Shargel, a lawyer who

represented Oscar S. Wyatt Jr., 83, who received a year and a day for violating

the rules of the United Nations oil-for-food program. “It’s a pretty cruel end

to a life if a person’s going to die in jail, when you don’t have a family

member, a loved one, to hold your hand or see you through it,” he said.

For Justice Bartley to spare Mr. Marshall prison time, he most likely would have

to throw out the jury’s verdict in the interest of justice, a step that judges

almost never take.

Mr. Marshall’s lawyers are expected, at the very least, to ask Justice Bartley

to allow their client to remain free until all appeals are exhausted. Beyond

that, there is not much Mr. Marshall’s defense team can do other than hope that

an appellate court finds in his favor.

“You can be sure that we’re looking into all the avenues that can be pursued,”

said Kenneth E. Warner, one of Mr. Marshall’s lawyers.

Mr. Marshall’s best chance to avoid prison probably would have been a plea deal

before trial, but there were never any serious negotiations.

As an inmate, Mr. Marshall may still be able to spend some nights in his own

bed. If he receives the minimum sentence, he would be immediately eligible for

the work release program, which allows inmates to spend a certain number of days

each week out of prison so they can work, said Linda M. Foglia, a spokeswoman

for the state’s Department of Correctional Services.

Mr. Marshall, who would most likely be placed in a minimum- or medium-security

prison with barracks-style housing that holds up to 60 inmates, would be one of

the oldest prisoners in New York: Fewer than 1.5 percent of the state’s inmates

are older than 65, according to Ms. Foglia.

In the past, some judges have taken creative steps to spare an elderly

defendant.

Leslie Crocker Snyder, a former State Supreme Court justice in Manhattan, said

that in one of her cases, the Rockefeller drug laws required her to sentence a

man in his 80s to 15 years to life for a low-level offense. So she asked the

prosecutors if they would consent to vacating the verdict and allow the man

plead guilty to a lesser charge for a shorter sentence. They did, she said. But

that was a “highly unusual” move, said Ms. Snyder, who would not address the

Astor case specifically.

John W. Moscow, a former prosecutor in the Manhattan district attorney’s office,

said he decided against trying Clark Clifford, who was indicted in the B.C.C.I.

case, because he was 86 and had had quadruple bypass surgery, and his doctors

said he could not spend more than two hours a day in court. But Mr. Moscow said

he would not feel sorry if Mr. Marshall had to serve some time.

“Tough,” Mr. Moscow said. “The law does not make an exception for him.”

Leonard F. Joy, the federal defender in New York, said that for the oldest

defendants even a short prison term “may very well be a life sentence.”

“Of course, when you get to be that age, you ought to know better,” added Mr.

Joy, who is 79.

The age issue arose in May when a federal judge in Manhattan was asked to spare

an 85-year-old New Jersey man from going to prison. The defendant, Ben-Ami

Kadish, hobbled into the courtroom and admitted providing classified United

States military documents to an Israeli agent in the early 1980s. (He pleaded

guilty to a lesser offense.)

His lawyer, Jack T. Litman, cited Mr. Kadish’s poor health and other factors.

“He is in the very twilight of his life, and to separate him from his wife even

for a short period of time would be devastating to both of them,” Mr. Litman

argued.

The judge, William H. Pauley III, saying that prison “would serve no purpose,”

fined Mr. Kadish $50,000.

In the case of Ciro Perrone, a captain in the Genovese crime family, the

87-year-old mobster confronted a judge not much younger than he was.

Mr. Perrone had been convicted in a racketeering case, and faced about six years

in prison.

His lawyer asked for one year, citing Mr. Perrone’s age and health, and noting

that Mr. Perrone’s wife had Alzheimer’s disease. In court papers, federal

prosecutors in Manhattan called the proposed sentence “ludicrously lenient.”

The judge, Robert P. Patterson Jr., 84, imposed a five-year sentence. Then he

addressed the defendant.

“Let me just say, Mr. Perrone, I’m not too young either,” the judge said. “And I

have a wife who suffers from Alzheimer’s, so I know what you go through.”

But he said this type of crime was serious, and warranted a “significant enough

sentence” to deter such conduct.

“Having said that,” Judge Patterson said, “I feel for you and I wish you the

best.”

Weighing Prison When the Convict Is Over 80,

NYT, 10.10.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/10/nyregion/10astor.html

Susan Atkins, Manson Follower, Dies

September 26, 2009

The New York Times

By MARGALIT FOX

Susan Atkins, a member of Charles Manson’s murderous “family” who spent the

last four decades in prison for her role in one of the most sensational crimes

of the 20th century, the killings of the actress Sharon Tate and seven others in

1969, died Thursday at a women’s prison in Chowchilla, Calif. She was 61.

Terry Thornton, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections, told

The Associated Press that the cause was brain cancer.

Before being moved to a medical clinic at the California Central Women’s

Facility in Chowchilla a year ago, Ms. Atkins had been incarcerated at the

California Institution for Women, in Corona. .

Twenty-one at the time of the killings, Ms. Atkins was the best known of the

three young women convicted with Mr. Manson. Her grand jury testimony helped

secure an indictment against Mr. Manson and several adherents — among them Ms.

Atkins herself — in what came to be known as the Tate-LaBianca murders, a

killing spree spanning two consecutive August nights.

On Aug. 8, 1969, acting on Mr. Manson’s orders, Ms. Atkins and several “family”

members broke into Ms. Tate’s home near Beverly Hills. In the early hours of

Aug. 9, they killed five people: Ms. Tate, who was eight and a half months

pregnant; Abigail Folger, an heiress to the Folger coffee fortune; Jay Sebring,

a celebrity hairstylist; Voyteck Frykowski; and Steven Parent. Ms. Tate’s

husband, the director Roman Polanski, was abroad at the time.

On Aug. 10, also at Mr. Manson’s direction, Ms. Atkins and several associates

murdered Leno LaBianca, a wealthy supermarket owner, and his wife, Rosemary, in

their Los Angeles home.

The motive for the killings was not immediately apparent. Several of Mr.

Manson’s followers later testified that he had ordered them in the hope of

starting an apocalyptic race war, which he called Helter Skelter after the

Beatles song.

The murders and the ensuing seven-month trial drew the fevered attention of the

news media. They were the subject of a best-selling nonfiction book, “Helter

Skelter” (Norton, 1974), by the prosecutor in the case, Vincent Bugliosi, with

Curt Gentry. They also engendered a spate of movies, songs and even an opera.

Susan Denise Atkins was born on May 7, 1948, in San Gabriel, Calif., and reared

mainly in Northern California. The middle of three children, Ms. Atkins has said

publicly that both her parents were alcoholics and that she was sexually abused

by a male relative when she was a girl.

A quiet, middle-class girl, Susan sang in her school glee club and church choir.

When she was a teenager, her mother died of cancer. Afterward, Susan’s father,

financially depleted by his wife’s illness, moved the family frequently, often

leaving Susan and her younger brother with relatives as he looked for work.

At 18, Susan quit high school and left home, winding up in the Haight-Ashbury

district of San Francisco. She supported herself through odd jobs like

secretarial work and topless dancing. Soon afterward, she met Mr. Manson and

joined his band of adherents, who settled for a time at the Spahn Movie Ranch, a

dilapidated former film set north of Los Angeles. As a member of the “family,”

Ms. Atkins was given a new name, Sadie Mae Glutz.

In 1968, Ms. Atkins gave birth to a son. Mr. Manson — who by all accounts was

not the father — had her name the child Zezozose Zadfrack Glutz. While he was

still a baby, the child was removed from Ms. Atkins’s care and later adopted.

The first murder in which Ms. Atkins was involved was that of Gary Hinman, a

friend of Mr. Manson’s. On July 25, 1969, according to news accounts, Mr. Manson

dispatched Ms. Atkins and other followers to Mr. Hinman’s home to demand money.

After torturing Mr. Hinman for several days, one of the group, Bobby Beausoleil,

killed him. The Tate-LaBianca murders took place two weeks later.

In October, Ms. Atkins was arrested for the Hinman murder. In jail, according to

Mr. Bugliosi’s book and other accounts, she boasted to cellmates of having

stabbed Ms. Tate, tasted her blood and used the blood to write the word “Pig” on

the front door of the house.

Ms. Atkins, Mr. Manson and other “family” members were charged with the seven

Tate-LaBianca murders. In December, Ms. Atkins testified before a grand jury

that she had stabbed Ms. Tate repeatedly as she begged for the life of her

unborn child. Ms. Atkins later recanted the confession.

The trial began in June 1970. On Jan. 25, 1971, after deliberating for nine

days, the jury found Ms. Atkins, Mr. Manson and Patricia Krenwinkel guilty of

the five Tate murders. It also found the three of them and Leslie Van Houten

guilty of the two LaBianca murders. (Another “family” member, Charles Watson,

was convicted separately of all seven murders.) In other trials, Ms. Atkins, Mr.

Manson, Mr. Beausoleil and Bruce Davis were convicted of Mr. Hinman’s murder.

Mr. Manson and the three women were sentenced to death. In 1972, after the death

penalty was temporarily abolished in California, their sentences were reduced to

life imprisonment.

In 1974, Ms. Atkins became a born-again Christian, according to her memoir,

“Child of Satan, Child of God” (Logos International, 1977; with Bob Slosser).

She denounced Mr. Manson, formed a prison ministry and did charitable work of

all kinds. She was denied parole 11 times.

In 1981, Ms. Atkins was married in the prison chapel to a flamboyant Texan named

Donald Lee Laisure. Mr. Laisure, who said he first met Ms. Atkins in the

mid-1960s, described himself in interviews as a multimillionaire; he spelled his

surname with a dollar sign in place of the “s.”

Mr. Laisure also told reporters that Ms. Atkins was his 29th wife, in some

accounts, his 36th. The marriage was dissolved after a few months. In 1987, Ms.

Atkins married James W. Whitehouse, who is now a lawyer.

Susan Atkins, Manson

Follower, Dies, NYT, 26.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/26/us/26atkins.html

Op-Ed Contributor

The Recession Behind Bars

September 6, 2009

The New York Times

By KENNETH E. HARTMAN

Lancaster, Calif.

EVERY weekday morning the prison’s not on lockdown, the yard holds its

collective breath waiting for the pale-orange package cart to appear through

multiple layers of chain-link and razor-wire fences. For most prisoners, this

lumbering vessel is their only tangible, physical connection back to the free

world. The last couple of years the cart has arrived less often and with visibly

lighter loads.

We get broadcast television, so the state of the economy outside is no secret.

Our families and friends tend to come from the segments of society that are the

worst off in the best of times, and worse off still in times like these. Our

mothers and fathers, wives and children, those to whom the ties that bind

haven’t been unbound by the course of our lives, tell us how hard it is out

there.

The first inkling of financial difficulties in here surfaced in the chow hall.

All of a sudden prison officials became concerned about our overeating. In the

last couple of years, our brown plastic trays have started to look and feel a

lot emptier. Even the old staples, beans and rice, shrank into bite-sized

portions. Luxury items like frosted cake and meat cut from the carcass of a

once-living thing vanished. The new menus, chock full of potatoes and meat

substitutes, seem right out of a Spartan’s cookbook.

Prison is a world reflected in a looking glass, however. The past 25 years were

generally prosperous for California; the economy boomed and fortunes were made

in the sunny San Fernando Valley. But during this time, the lives of prisoners

became much drearier. We were forced into demeaning uniforms, with neon orange

letters spelling out “prisoner,” and lost most of the positive programs like

conjugal visits and college education that we had had since the ’70s. Money was

flowing outside the prison walls, but new “get tough” policies against criminals

were causing our population, and our costs, to soar.

It is a quirk of California politics that it is among the bluest of states but

has some of the reddest of laws. No politician here ever lost an election for

being too tough on crime or prisoners. Consequently, all through the ’80s and

’90s billions of dollars were poured into a historic prison-building boom.

Private airplane pilots tell me it’s easy to navigate at night from San Diego to

Los Angeles and on up the Central Valley to Sacramento by simply following the

prisons’ glowing lights. Good times in the free world meant, in here,

ever-longer sentences, meaner regulations and ever-decreasing interest in

rehabilitation. “Costs be damned; lock ’em up and be done with it” became the

unofficial motto of the Department of Corrections.

The last time I received a visit from my family, in early July, the

air-conditioning in the visiting room had been broken for more than a month.

This matters because my prison is in the high desert north of Los Angeles.

Temperatures here in the summer commonly rise above 100 dusty, windy degrees.

Pack 150 people into an airless room and you’ve got the makings for human

meltdown. Two industrial-sized fans only made a hot situation noisy, too.

The next day I asked one of the administrators what could be done to get the

air-conditioning fixed, and he told me an amazing story. The free-world

contractor who services the prison’s air-conditioning systems had refused to

come out to replace the part that was broken, because the state owed the company

tens of thousands of dollars in back fees and could pay only in i.o.u.’s. There

would be no cool air until the state’s budget negotiations were concluded.

Now that the economy is suffering, there is talk of reforming the prisons, of

reviving the discredited concept of rehabilitation, of letting some prisoners

out early. Some people have even mentioned doing away with the death penalty

because of the exorbitant cost to the state of guaranteed appeals. For those of

us who have endured a generation of policies intended explicitly to inflict

pain, this has a surreal quality to it. After all, it was only a year ago that

the state authorities were planning the next phase of prison expansion.

Obviously, all the passionate arguments that have been made about the moral

wrongs of mass incarceration, of disproportionately affected communities, of

abysmal treatment and civil rights violations were just so much hot air. Only

when society ran out of ready cash did prison reform become worthy of serious

consideration. What this says about the free world is unclear to me, but it

doesn’t feel like a good thing.

The talk in here contains an element of schadenfreude. When the TV shows

legislators complaining about how deep in the hole the state budget is, laughter

fills the day room. Our captor turns out to be simply inept.

From the four-inch-wide window in the back of my cell, I watched, for seven

years, the construction of a housing tract across the street — a subdivision we

call Prison View Estates. We marvel at the hubris of building chockablock stucco

mini-mansions within shouting distance of a maximum-security prison. Today, a

year after the gaudy balloons from the grand opening deflated, the row of houses

directly across from my window looks to be unoccupied.

From my cell I can also observe the inner roadway on which prison vehicles pass.

A fleet of new, shining-white super-security transportation vans still drives by

daily. Leviathan hasn’t quite adjusted to the Golden State’s diminished

firmament.

Kenneth E. Hartman, the author of the forthcoming “Mother California: A Story

of Redemption Behind Bars,” was sentenced in 1980 to life without parole for

murder.

The Recession Behind

Bars, NYT, 6.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/opinion/06hartman.html

California State Assembly Approves Prison Legislation

September 1, 2009

The New York Times

By SOLOMON MOORE

LOS ANGELES — The California State Assembly narrowly passed legislation on

Monday to reduce the state prison population by 27,000 inmates and the state

corrections budget by about $1 billion.

After several hours of debate in Sacramento, the bill passed 41 to 35, without

any Republican support and only about half of the Democratic majority.

The bill was significantly weaker than a version that the State Senate passed

last month. It will shorten sentences for some nonviolent prison inmates who

participate in rehabilitation programs, reduce parole supervision for some

infirm and nonviolent offenders, and increase monitoring for parolees with

violent criminal records.

Law enforcement groups played a central role in pushing Democrats to strip the

bill of provisions that would have reduced sentences for some nonviolent

offenses and would have established a public safety commission to redo prison

sentencing guidelines.

Those excised proposals reduced the savings of the bill for the strapped state

by about $220 million, and the prison population reductions by about 11,000

inmates, said the speaker, Karen Bass, a Democrat who led negotiations last week

to remove the provisions.

The two houses will now have to reconcile the sizable differences between the

two bills. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, initially supported the

more sweeping Senate bill.

California’s prisons now hold about 155,000 inmates, about twice the number they

were designed to hold. The system is so overcrowded that a federal court imposed

a cap and ordered the state to reduce its prison population by more than 40,000

offenders. Contributing to the prison population glut is the large number of

failed parolees; 70 percent of parolees return to prison before completing their

supervised release programs.

At the forefront of the law enforcement groups who played an important part in

shaping the bill is the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, a

30,000-member prison guard union with one of the most powerful voices in state

politics.

Law enforcement groups say they consider the Senate version of the bill to be a

risk to public safety, especially in light of several recent killings in which

parolees are accused. One print advertisement paid for by the prison guard union

pictured two dice in midroll and a caption that accused Mr. Schwarzenegger of

making risky decisions about parole reform that would lead to innocent lives

being lost.

“For the past few years, you’ve been quietly dumping more and more parolees on

the street, with less and less supervision and no business being free,” the

caption read. “Now 17-year-old Lily Burk is dead.”

Ms. Burk’s body was found in her car at the edge of downtown Los Angeles in

July; the police hours later arrested Charles Samuel, a state parolee, on

suspicion of her murder.

The prison guard union and the governor have been at odds since contract

negotiations broke down in 2007, when Mr. Schwarzenegger rejected demands for

pay raises at the state’s 33 prisons.

Last year, the union threatened to finance a recall campaign against Mr.

Schwarzenegger similar to the one that eventually led to the ouster of his

predecessor, Gray Davis, in 2003.

The union also criticized Mr. Schwarzenegger for proposing the layoff of 1,300

correctional officers.

The union declined to comment for this article.

Legislators had their own reservations about the bill.

In Monday’s debate, several brought up recent revelations that Phillip Garrido,

paroled for 1976 crimes of kidnapping and rape, is accused of abducting an

11-year-old and imprisoning her in a backyard encampment for 18 years. And they

warned that men like him would be unleashed on California’s streets if the bill

passed.

“What this bill will do is move unrehabilitated felons into your communities,”

said Jim Nielsen, a Republican.

Isadore Hall III, a Democrat who represents South Los Angeles and Compton, said

that Republicans who warned about increased crime and compromised public safety

as a result of the bill were using “swift-boat scare tactics.”

“This bill is not about violent crime,” he said. “This bill is about nonviolent,

non-sex offenders.”

California State

Assembly Approves Prison Legislation, NYT, 1.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/01/us/01prison.html

Letters

Reforming New York’s Juvenile Prisons

August 31, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “4 Youth

Prisons in New York Used Excessive Force” (front page, Aug. 25):

The report by the United States Department of Justice that the constitutional

rights of youth incarcerated in New York State’s institutional facilities have

been violated places an intensive spotlight on the serious deficiencies of our

state’s juvenile justice system.

The members of the Task Force on Transforming New York’s Juvenile Justice

System, appointed by Gov. David A. Paterson, recognize the significant progress

made in the last two years under the leadership of Gladys Carrión, commissioner

of the Office of Children and Family Services, but much still needs to be done.

Our report, due by the end of the year, will look at conditions of confinement —

the topic of the Justice Department investigation — but will also examine ways

to expand alternatives to institutional placement, ensure that confined youth

transition successfully to their communities upon release, and reduce the

disproportionate incarceration of youth of color.

As the Justice Department report confirms, the current system needs a complete

overhaul — it does not serve youth well, does not provide a safe workplace for

its staff, and does little to promote public safety. Jeremy Travis

New York, Aug. 26, 2009

The writer, chairman of the Governor’s Task Force on Transforming New York’s

Juvenile Justice System, is president of the John Jay College of Criminal

Justice, CUNY.

•

To the Editor:

Our failure to provide adequate mental health services to youths in detention

signals a growing danger we cannot afford to overlook, even in our present

cash-strapped state.

If the primary goal of our juvenile justice system is to rehabilitate young

offenders, many of whom enter the system with significant mental health and

behavioral problems, it is incumbent upon us to meet these needs as a matter of

human rights, yes, but also to prevent the devastating future costs of untreated

mental health problems and escalating criminal behavior.

Following the examples of states that have developed more comprehensive,

coordinated strategies, New York needs to prioritize its need for a system of

mental health care for juvenile justice-involved youth as well as for youth who

have yet to come in contact with the justice system. We as a society cannot bear

the cost, both human and monetary, of foreclosing on their futures altogether.

Janice L. Cooper

Susan Wile Schwarz

New York, Aug. 25, 2009

The writers are, respectively, interim director and research analyst, National

Center for Children in Poverty, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia

University.

•

To the Editor:

Your article spotlighted how juveniles behind bars are subjected to serious

injury by prison personnel. Yet equally disturbing but underreported is that the

same investigation found that these children aren’t only being physically

abused, they are also being overmedicated.

In a flagrant exploitation of imprisoned children’s rights, the investigation

found that the continuing and voluminous practice of dispensing psychiatric

drugs to child inmates represents “substantial departures from generally

accepted professional standards.”

The investigation also found a “pervasive lack of documentation” outlining any

rationale for medicating the children. This strongly suggests that the drugs are

being used as chemical restraints to control behavior rather than as part of an

individualized mental health treatment plan.

Under federal and international law, many psychotropic medications are

considered “controlled substances” and when prescribed require adherence to

regulatory protocols. These drugs are highly addictive, directly affect the

brain and can have serious and sometimes deadly effects. And most are not

approved for use in children by the Food and Drug Administration.

Now New York’s Office of Children and Family Services has the evidence it needs

to act quickly and assuredly to protect children in its custody from medically

unjustified exposure to these dangerous drugs and to the excessive use of force.

Angela Olivia Burton

Flushing, Queens, Aug. 27, 2009

The writer is an associate professor at the CUNY Law School.

•

To the Editor:

The abuse suffered by the adolescents at the residential “treatment”centers

(“New York’s Disgrace,” editorial, Aug. 25) is really only the end of a lifetime

of abuse and neglect suffered by these children.

From infancy on they have lived in poverty with neglectful and abusive families,

lived in substandard housing and neighborhoods, and attended substandard

schools. They frequently have been exposed to violence themselves.

They have minimal academic skills. They have in many ways been abandoned by

society. The disgrace lies not only in the detention centers but also in our

indifference to these adolescents and allowing them to have to endure a lifetime

of neglect and failure.

The solution doesn’t lie in fixing the juvenile justice system but rather in

preventing these children from getting involved with that system in the first

place. This can be done only by providing these children and their families with

adequate social support and making use of effective prevention programs. David

Brandt

Croton on Hudson, N.Y.

Aug. 26, 2009

The writer is professor emeritus of psychology, John Jay College of Criminal

Justice.

Reforming New York’s

Juvenile Prisons, NYT, 31.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/31/opinion/l31juvenile.html

Hawaii to Remove Inmates Over Abuse Charges

August 26, 2009

The New York Times

By IAN URBINA

Hawaii prison officials said Tuesday that all of the state’s 168 female

inmates at a privately run Kentucky prison will be removed by the end of

September because of charges of sexual abuse by guards. Forty inmates were

returned to Hawaii on Aug. 17.

This month, officials from the Hawaii Department of Public Safety traveled to

Kentucky to investigate accusations that inmates at the prison, the Otter Creek

Correctional Center in Wheelwright, including seven from Hawaii, had been

sexually assaulted by the prison staff.

Otter Creek is run by the Corrections Corporation of America and is one of a

spate of private, for-profit prisons, mainly in the South, that have been the

focus of investigations over issues like abusive conditions and wrongful deaths.

Because Eastern Kentucky is one of the poorest rural regions in the country, the

prison was welcomed by local residents desperate for jobs.

Hawaii sent inmates to Kentucky to save money. Housing an inmate at the Women’s

Community Correctional Center in Kailua, Hawaii, costs $86 a day, compared with

$58.46 a day at the Kentucky prison, not including air travel.

Hawaii investigators found that at least five corrections officials at the

prison, including a chaplain, had been charged with having sex with inmates in

the last three years, and four were convicted. Three rape cases involving guards

and Hawaii inmates were recently turned over to law enforcement authorities. The

Kentucky State Police said another sexual assault case would go to a grand jury

soon.

Kentucky is one of only a handful of states where it is a misdemeanor rather

than a felony for a prison guard to have sex with an inmate, according to the

National Institute of Corrections, a policy arm of the Justice Department. A

bill to increase the penalties for such sexual misconduct failed to pass in the

Kentucky legislature this year.

The private prison industry has generated extensive controversy, with critics

arguing that incarceration should not be contracted to for-profit companies.

Several reports have found contract violations at private prisons, safety and

security concerns, questionable cost savings and higher rates of inmate

recidivism. “Privately operated prisons appear to have systemic problems in

maintaining secure facilities,” a 2001 study by the Federal Bureau of Prisons

concluded.

Those views are shared by Alex Friedmann, associate editor of Prison Legal News,

a nonprofit group based in Seattle that has a monthly magazine and does

litigation on behalf of inmates’ rights.

“Private prisons such as Otter Creek raise serious concerns about transparency

and public accountability, and there have been incidents of sexual misconduct at

that facility for many years,” Mr. Friedmann said.

But proponents say privately run prisons provide needed beds at lower cost.

About 8 percent of state and federal inmates are held in such prisons, according

to the Justice Department.

“We are reviewing every allegation, regardless of the disposition,” said Lisa

Lamb, a spokeswoman for the Kentucky Department of Corrections, which she said

was investigating 23 accusations of sexual assault at Otter Creek going back to

2006.

The move by Hawaii authorities is just the latest problem for Kentucky prison

officials.

On Saturday, a riot at another Kentucky prison, the Northpoint Training Center

at Burgin, forced officials to move about 700 prisoners out of the facility,

which is 30 miles south of Lexington.

State investigators said Tuesday that they were questioning prisoners and staff

members and reviewing security cameras at the Burgin prison to see whether

racial tensions may have led to the riot that injured 16 people and left the

lockup in ruins. A lockdown after a fight between white and Hispanic inmates had

been eased to allow inmates access to the prison yard on Friday, the day before

the riot. Prisoners started fires in trash cans that spread. Several buildings

were badly damaged.

While the riot was an unusual event — the last one at a Kentucky state prison

was in 1983 — reports of sexual abuse at Otter Creek are not new. “The number of

reported sexual assaults at Otter Creek in 2007 was four times higher than at

the state-run Kentucky Correctional Institution for Women,” Mr. Friedmann said.

In July, Gov. Linda Lingle of Hawaii, a Republican, said that bringing prisoners

home would cost hundreds of millions of dollars that the state did not have, but

that she was willing to do so because of the security concerns.

Prison overcrowding led to federal oversight in Hawaii from 1985 to 1999. The

state now houses one-third of its prison population in mainland facilities.

The pay at the Otter Creek prison is low, even by local standards. A federal

prison in Kentucky pays workers with no experience at least $18 an hour, nearby

state-run prisons pay $11.22 and Otter Creek pays $8.25. Mr. Friedmann said

lower wages at private prisons lead to higher employee turnover and less

experienced staff.

Tommy Johnson, deputy director of the Hawaii Department of Public Safety, said

he found that 81 percent of the Otter Creek workers were men and 19 percent were

women, the reverse of what he said the ratio should be for a women’s prison. Mr.

Johnson asked the company to hire more women, and it began a bonus program in

June to do so.

Hawaii to Remove Inmates

Over Abuse Charges, NYT, 26.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/26/us/26kentucky.html?hp

4 Youth Prisons in New York Used Excessive Force

August 25, 2009

The New York Times

By NICHOLAS CONFESSORE

Excessive physical force was routinely used to discipline children at several

juvenile prisons in New York, resulting in broken bones, shattered teeth,

concussions and dozens of other serious injuries over a period of less than two

years, a federal investigation has found.

A report by the United States Department of Justice highlighted abuses at four

juvenile residential centers and raised the possibility of a federal takeover of

the state’s entire youth prison system if the problems were not quickly

addressed.

The report, made public on Monday, came 18 months into a major effort by state

officials to overhaul New York’s troubled juvenile prison system, which houses

children convicted of criminal acts, from truancy to murder, who are too young

to serve in adult jails and prisons.

Investigators found that physical force was often the first response to any act

of insubordination by residents, who are all under 16, despite rules allowing

force only as a last resort.

“Staff at the facilities routinely used uncontrolled, unsafe applications of

force, departing from generally accepted standards,” said the report, which was

given to Gov. David A. Paterson on Aug. 14.

“Anything from sneaking an extra cookie to initiating a fistfight may result in

a full prone restraint with handcuffs,” the reportsaid. “This one-size-fits-all

approach has, not surprisingly, led to an alarming number of serious injuries to

youth, including concussions, broken or knocked-out teeth, and spiral fractures”

(bone fractures caused by twisting).

In a statement issued on Monday, Gladys Carrión, the commissioner of the Office

of Children and Family Services, which oversees the juvenile prisons, said that

the administration had inherited a youth justice system “rife with substantial

systemic problems” but acknowledged that efforts to overhaul it had so far

fallen short.

“We have made great strides,” said Ms. Carrión, “but much more still needs to be

done.”

In one case described in the report, a youth was forcibly restrained and

handcuffed after refusing to stop laughing when ordered to; the youth sustained

a cut lip and injuries to the wrists and elbows. Workers forced one boy, who had

glared at a staff member, into a sitting position and secured his arms behind

his back with such force that his collarbone was broken.

Another youth was restrained eight times in three months despite signs that she

might have been contemplating suicide. “In nearly every one of the eight

incidents,” the report found, “the youth was engaged in behaviors such as head

banging, putting paper clips in her mouth, tying a string around her neck, etc.”

The four centers cited in the report are the Lansing Residential Center and the

Louis Gossett Jr. Residential Center in Lansing, and two residences, one for

boys and one for girls, at Tryon Residential Center in Johnstown.

Officials at the centers also routinely failed to follow state rules requiring

reviews whenever force is used, the report said. In some cases, the same staff

member involved in an episode conducted the review of it. And even when a review

determined that excessive force had been used, the staff members responsible

sometimes faced no punishment.

In one case, a youth counselor with a documented record of using excessive force

was recommended for firing after throwing a youth to the ground with such force

that stitches were required on the youth’s chin. But after the counselor’s union

intervened, the punishment was downgraded to a letter of reprimand, an $800 fine

and a two-week suspension that was itself suspended.

The federal inquiry began in December 2007 following a spate of incidents at

some of the 28 state-run juvenile residential centers, which house about 1,000

youths.

In November 2006, an emotionally disturbed teenager, Darryl Thompson, 15, died

after two employees at the Tryon center pinned him down on the ground. The death

was ruled a homicide, but a grand jury declined to indict the workers. The boy’s

mother is suing the state.

During the same period, a separate joint investigation by the state inspector

general and the Tompkins County district attorney found that the independent

ombudsman’s office charged with overseeing youth prison centers had virtually

ceased to function. In a report by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil

Liberties Union issued in September 2006, New York’s youth residential centers

were rated among the worst in the world.

Those scandals spurred a drive within Ms. Carrión’s department to overhaul the

system. It reconstituted the ombudsman’s office and issued clearer policies on

the use of physical force, leading to a sharp drop in instances where restraints

were applied.

Under the overhaul, officials have also sought to close underused centers and

redirect resources to counseling and other services, though they have faced

fierce resistance from public employees’ unions and their allies in the

Legislature. A task force appointed last year by Mr. Paterson is set to issue

further recommendations by the end of this year.

“The problem is the unions and some of the staff they represent,” said Mishi

Faruquee, director of Youth Justice Programs at the Children’s Defense Fund-New

York, and a member of the task force. “They are very entrenched in the way they

do things and the way they have been trained to do their jobs,” she said. “They

have been very resistant to changing the policy on the use of force.”

In a statement, Stephen A. Madarasz, director of communications for the Civil

Service Employees Union, which represents many of the workers at the centers,

said union officials had not had an opportunity to review the full report.

The federal report revealed that despite efforts to overhaul the system,

problems at some of the centers remained so severe that residents’

constitutional rights were being violated. Under federal law, New York has 49

days to respond with a plan of action to comply with the report’s

recommendations.

If the state fails to do so, the Justice Department can initiate a lawsuit that

could result in a federal takeover of the state’s juvenile prison system.

Even as the four centers singled out in the report relied excessively on

physical force, federal investigators found, they failed to provide youths with

adequate counseling and mental health treatment, something the vast majority of

residents require. Three-quarters of children entering New York’s youth justice

system have drug or alcohol problems, more than half have diagnosed

psychological problems and a third have developmental disabilities, according to

figures published by Office of Children and Family Services.

“The majority of psychiatric evaluations at the four facilities did not come

close to meeting” professional standards, investigators determined, and

“typically lacked basic, necessary information.”

4 Youth Prisons in New

York Used Excessive Force, NYT, 25.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/nyregion/25juvenile.html

Rioting Inmates Set Central Ky. Prison Ablaze

August 22, 2009

Filed at 12:08 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

BURGIN, Ky. (AP) -- Rioting inmates set fire to trash cans and other items

inside a central Ky. prison, and damage to some buildings was so extensive that

officials were busing many of the facility's 1,200 prisoners elsewhere, police

said Saturday.

By early morning, firefighters had extinguished the fires at the medium-security

Northpoint Training Center in a rural area 30 miles south of Lexington, state

police Lt. David Jude said.

Eight inmates were treated for minor injuries, and eight staff were also injured

in the melee, although none was admitted to the hospital, said Cheryl Million, a

spokeswoman for the Kentucky Department of Corrections.

Officers in riot gear rushed the prisoners with tear gas about 9 p.m. Friday,

and all the inmates were subdued in less than two hours, authorities said.

Six buildings had burned, including a kitchen, medical center, canteen and

visitation area. Million also said all dormitories were damaged ''to the extent

of being inhabitable,'' except for one 196-bed unit.

A bus carrying some 42 inmates deemed higher security risks left the property

shortly after 6 a.m., heading to an undisclosed facility. It wasn't clear how

many other inmates would have to be moved.

''To me it would seem like a pretty daunting task to move that many inmates

suddenly from one place,'' Jude said.

Gov. Steve Beshear praised corrections officials and state police for handling

the situation without any serious injuries.

''Their work last night in the face of the most trying circumstances was truly

remarkable,'' Beshear said in a statement. ''Corrections officials are currently

assessing the extent of damage to determine the needs going forward for safely

housing prisoners in the coming days and for the long term.''

Some of the inmates would be able to stay at Northpoint, Million said.

''As we continue to assess the situation, other inmates could possibly be

transferred,'' Million said. ''Decisions to transfer would be based on

facilities security levels and inmates' needs.''

Jude said the prisoners were being kept in an outdoor courtyard surrounded by

prison guards. Police formed a perimeter around the outside of the facility to

make sure no one escaped.

Portable toilets were brought in, and prison officials were using temporary food

stations to feed the prisoners because the fire in the kitchen destroyed much of

the prison's food supply.

''Everything seems to be at a calm,'' Jude said. ''They're sitting down, kind of

going with the program right now.''

Jude didn't immediately say what caused of the rioting, which began around 6:30

p.m. Friday.

Prison spokeswoman Mendolyn Cochran said Friday the prison had been on lockdown

since Tuesday, when one group of inmates assaulted two others, The

Advocate-Messenger of Danville reported. Later Friday, some inmates started

setting fires in trash cans, she said.

Million wouldn't confirm the report, saying only that some of the fires started

in trash cans and that some inmates had access to matches because smoking is

allowed in parts of the prison.

The melee in Kentucky comes two weeks after more than 1,000 inmates rioted at

the California Institution for Men in Southern California. The prison was

designed to hold about half as many inmates, although investigators say they

don't know if crowding helped spark the racially charged riot.

Northpoint has more than 1,100 general population inmates housed in six open-bay

dormitories, according to its Web site. Another 60 special management inmates

are housed in single cells in a separate structure, and 40 minimum-security

inmates are housed in another separate structure.

It opened in 1983 and has a staff of 285.

Rioting Inmates Set

Central Ky. Prison Ablaze, NYT, 22.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/08/22/us/AP-US-Ky-Prison-Melee.html

Editorial

12 and in Prison

July 28, 2009

The New York Times

The Supreme Court sent an important message when it ruled in Roper v. Simmons

in 2005 that children under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed were

not eligible for the death penalty. Justice Anthony Kennedy drew on compassion,

common sense and the science of the youthful brain when he wrote that it was

morally wrong to equate the offenses of emotionally undeveloped adolescents with

the offenses of fully formed adults.

The states have followed this logic in death penalty cases. But they have

continued to mete out barbaric treatment — including life sentences — to

children whose cases should rightly be handled through the juvenile courts.

Congress can help to correct these practices by amending the Juvenile Justice

and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, which is up for Congressional

reauthorization this year. To get a share of delinquency prevention money, the

law requires the states and localities to meet minimum federal protections for

youths in the justice system. These protections are intended to keep as many

youths as possible out of adult jails and prisons, and to segregate those that

are sent to those places from the adult criminal population.

The case for tougher legislative action is laid out in an alarming new study of

children 13 and under in the adult criminal justice system, the lead author of

which is the juvenile justice scholar, Michele Deitch, of the Lyndon B. Johnson

School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. According to the

study, every state allows juveniles to be tried as adults, and more than 20

states permit preadolescent children as young as 7 to be tried in adult courts.

This is terrible public policy. Children who are convicted and sentenced as

adults are much more likely to become violent offenders — and to return to an

adult jail later on — than children tried in the juvenile justice system.

Despite these well-known risks, policy makers across the country do not have

reliable data on just how many children are being shunted into the adult system

by state statutes or prosecutors, who have the discretion to file cases in the

adult courts.

But there is reasonably reliable data showing juvenile court judges send about

80 children ages 13 and under into the adult courts each year. These statistics

explode the myth that those children have committed especially heinous acts.

The data suggest, for example, that children 13 and under who commit crimes like

burglary and theft are just as likely to be sent to adult courts as children who

commit serious acts of violence against people. As has been shown in previous

studies, minority defendants are more likely to get adult treatment than their

white counterparts who commit comparable offenses.

The study’s authors rightly call on lawmakers to enact laws that discourage

harsh sentencing for preadolescent children and that enable them to be

transferred back into the juvenile system. Beyond that, Congress should amend

the juvenile justice act to require the states to simply end these inhumane

practices to be eligible for federal juvenile justice funds.

12 and in Prison, NYT,

28.7.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/28/opinion/28tue1.html?hpw

Number of

Life Terms Hits Record

July 23, 2009

The New York Times

By SOLOMON MOORE

CORONA,

Calif. — Mary Thompson, an inmate at the California Institution for Women here,

was convicted of two felonies for a robbery spree in which she threatened

victims with a knife. Her third felony under California’s three-strikes law was

the theft of three tracksuits to pay for her crack cocaine habit in 1982.

Like one out of five prisoners in California, and nearly 10 percent of all

prisoners nationally in 2008, Ms. Thompson is serving a life sentence. She will

be eligible for parole by 2020.

More prisoners today are serving life terms than ever before — 140,610 out of

2.3 million inmates being held in jails and prisons across the country — under

tough mandatory minimum-sentencing laws and the declining use of parole for

eligible convicts, according to a report released Wednesday by the Sentencing

Project, a group that calls for the elimination of life sentences without

parole. The report tracks the increase in life sentences from 1984, when the

number of inmates serving life terms was 34,000.

Two-thirds of prisoners serving life sentences are Latino or black, the report

found. In New York State, for example, 16.3 percent of prisoners serving life

terms are white.

Although most people serving life terms were convicted of violent crimes,

sentencing experts say there are many exceptions, like Norman Williams, 46, who

served 13 years of a life sentence for stealing a floor jack out of a tow truck,

a crime that was his third strike. He was released from Folsom State Prison in

California in April after appealing his conviction on the grounds of

insufficient counsel.

The rising number of inmates serving life terms is straining corrections budgets

at a time when financially strapped states are struggling to cut costs.

California’s prison system, the nation’s largest, with 170,000 inmates, also had

the highest number of prisoners with life sentences, 34,164, or triple the

number in 1992, the report found.

In four other states — Alabama, Massachusetts, Nevada and New York — at least

one in six prisoners is serving a life term, according to the report.

The California prison system is in federal receivership for overcrowding and

failing to provide adequate medical care to prisoners, many of whom are elderly

and serving life terms.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger this week repeated his proposal to reduce the inmate

population through a combination of early releases for nonviolent offenders,

home monitoring for some parole violators and more lenient sentencing for some

felonies. But there are no credible plans to increase the rate at which

prisoners serving life sentences are granted parole.

“When California courts sentence somebody to life with parole, it turns out

that’s not possible after all,” said Joan Petersilia, a Stanford law professor

and an expert on parole policy. “Board of parole hearings almost never grant

releases, and that’s the reason that California’s lifer population has grown out

of proportion to other states.”

Margo Johnson, 48, also an inmate at the women’s prison here, has served 24

years of a life sentence for a 1984 murder. She has been recommended for release