|

History > 2009 > USA > Health (I)

Mikhaela Reid

Cagle

16 January 2009

Op-Ed Contributor

Dead Body of Knowledge

March 27, 2009

The New York Times

By CHRISTINE MONTROSS

Providence, R.I.

AT the risk of sounding like a fuddy-duddy, I would like to say that

sometimes, medical imaging isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

As a resident in psychiatry, I depend on the technology to treat my patients.

From countless computers in the hospital’s hallways and at nurses’ stations, I

call up images of the people I treat: the black, white and gray CT scans of

their skulls, the nuanced M.R.I.’s of their spinal cords and ligaments, the

rotating Spect scans that show in three dimensions how well — or how poorly —

blood flows through their brains. I can leave the room of an 89-year-old woman

who has begun picking imaginary bugs out of the air, look into a screen, and see

the tumor that is causing her delirium.

Now however, many medical schools are beginning to argue that imaging technology

has improved to the point where it should be used in place of the dissection of

human cadavers as the central tool of instruction for young doctors-to-be. This

is a mistake. No matter how detailed and versatile they become, computer images

can never provide the indelible lessons that novice doctors learn from real

bodies.

Nearly every medical student in America begins his career by entering a room

full of cadavers and taking one of them apart, layer by layer, piece by piece.

Doctors have shared this experience for centuries, ever since Vesalius, Da Vinci

and Michelangelo defied religion and government, stole bodies from graves and

churches, and dissected by candlelight in an audacious pursuit of knowledge

about the human body. The process is what you would expect: messy and smelly,

tedious and time-consuming, emotionally and physically difficult. It is at times

awe-inspiring, and at other times profoundly upsetting. It is also, for the

medical schools, very expensive. Even though cadavers are donated, it can cost

more than $2,000 to prepare a body for dissection.

So medical schools are beginning to re-evaluate their anatomy curriculum in the

face of the perhaps inevitable argument: Why not reduce, or eliminate

altogether, the burdensome cost of dissecting cadavers and replace it with this

new and astounding technology? The computers and software — a considerable

expense, but one that need be incurred only once — allow students to study

images of the body from every angle and on every plane. They can peel away the

muscle on a virtual leg to see the bone beneath, then click a different button,

reattach the muscle and see how the limb moves.

Computers can show things that still and lifeless cadavers cannot — blood

pumping in real time through the heart’s chambers, for instance. And it is far

easier to visualize nerves and vessels when they’re color-coded on a computer

than it is to pick through the indistinguishable gray-green tangles inside a

formalin-embalmed cadaver. Because all of this can be done anywhere on any

screen, students can study anatomy in this way in the library, in their

apartments or, surely someday if not already, on their iPods and cellphones.

At the end of the academic year, there would be no need for old cadavers to be

cremated, for new human donors to be found, for deep cleaning the anatomy lab.

Come September, the whole system would simply reboot.

But what kind of doctors will they be, these students who have never experienced

human dissection? They would have been denied a safe and more gradual initiation

into the emotional strain that doctoring demands.

Someday, they’ll need to keep their cool when a baby is lodged wrong in a

mother’s birth canal; when a bone breaks through a patient’s skin; when

someone’s face is burned beyond recognition. Doctors do have normal reactions to

these situations; the composure that we strive to keep under stressful

circumstances is not innate. It has to be learned. The discomfort of taking a

blade to a dead man’s skin helps doctors-in-training figure out how to cope,

without the risk of intruding on a live patient’s feelings — or worse, his

health. We learn to heal the living by first dismantling the dead.

The dissection of cadavers also gives young doctors an appreciation for the

wonders of the human body in a way that no virtual image can match. It is

awe-inspiring to hold a human heart in one’s hands, to appreciate its fragility,

intricacy and strength.

But most important, the cadavers on their stainless steel tables are symbols of

altruism to medical students: They are reminders of how great a gift one can

give to a stranger in the hopes of healing. Isn’t that the most fundamental

lesson we want our doctors to carry to the bedsides of their patients?

Christine Montross, a resident in psychiatry at Brown University, is the

author of “Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality From the Human Anatomy Lab.”

Dead Body of Knowledge,

NYT, 27.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/27/opinion/27montross.html

As New Lawyer,

Senator Defended Big Tobacco

March 27, 2009

The New York Times

By RAYMOND HERNANDEZ

and DAVID KOCIENIEWSKI

The Philip Morris Company did not like to talk about what went

on inside its lab in Cologne, Germany, where researchers secretly conducted

experiments exploring the effects of cigarette smoking.

So when the Justice Department tried to get its hands on that research in 1996

to prove that tobacco industry executives had lied about the dangers of smoking,

the company moved to fend off the effort with the help of a highly regarded

young lawyer named Kirsten Rutnik.

Ms. Rutnik, who now goes by her married name, Gillibrand, threw herself into the

work. She traveled to Germany at least twice, interviewing the lab’s top

scientists, whose research showed a connection between smoking and cancer but

was kept far from public view.

She helped contend with prosecution demands for evidence and monitored testimony

of witnesses before a grand jury, following up with strategy memos to Philip

Morris’s general counsel.

The industry beat back the federal perjury investigation, a significant legal

victory at the time, but not one that Ms. Gillibrand is eager to discuss.

Now in the Senate seat formerly held by Hillary Rodham Clinton, Ms. Gillibrand

plays down her work as a lawyer representing Philip Morris, saying she was a

junior associate with little control over the cases she was handed and limited

involvement in defending the tobacco maker.

But a review of thousands of documents and interviews with dozens of lawyers and

industry experts indicate that Ms. Gillibrand was involved in some of the most

sensitive matters related to the defense of the tobacco giant as it confronted

pivotal legal battles beginning in the mid-1990s.

Ms. Gillibrand, who worked at the Manhattan firm of Davis Polk & Wardwell from

1991 to 2000, eventually oversaw a team of associate lawyers working on Philip

Morris cases, according to a colleague, and was a frequent point of contact

between the firm and Philip Morris executives.

In addition, Ms. Gillibrand represented Davis Polk on a high-level Philip Morris

committee whose work included shielding certain documents from disclosure,

according to several lawyers and industry observers. Serving on the panel placed

her alongside some of the country’s top tobacco industry lawyers.

And she was viewed so positively by Philip Morris that by 1999, when the tobacco

maker brought in an additional outside law firm to represent its interests, Ms.

Gillibrand was one of five Davis Polk lawyers designated to train the firm about

sensitive legal issues, according to a company memo.

When she moved in 2001 to a new firm, Boies Schiller, where she worked until

2005, one of Ms. Gillibrand’s clients was the Altria Group, Philip Morris’s

parent company, where she helped with securities and antitrust matters,

according to the firm.

Ms. Gillibrand, 42, a former upstate congresswoman who is still unknown to many

New Yorkers and is preparing to defend her Senate seat in an election next year,

is reluctant to discuss her work on behalf of the tobacco company. After

initially agreeing to be interviewed by The New York Times, the senator canceled

through her spokesman, Matt Canter, who said that focusing on Philip Morris

would not reflect the range of her work as a lawyer, which also included

representing pro bono clients, including abused women and families contending

with lead paint in their homes..

“Senator Gillibrand was serving as a young associate when she was assigned this

case,” Mr. Canter said. “It is a small part of her 15-year legal career.”

He stressed that like other tobacco lawyers, she was not at liberty to discuss

her work for Philip Morris because of attorney-client privilege.

But those who recall Ms. Gillibrand’s days as a young lawyer say she was capable

and eager as she plunged into the high-stakes and lucrative world of tobacco

defense work.

“The client was always in her office,” said her former Davis Polk colleague

Vincent Chang, who spoke glowingly of Ms. Gillibrand. “She was probably accorded

more responsibility than the average associate by far.”

Of course, many lawyers, including some who now serve in the Senate, have

defended unpopular clients. Still, in an approach that was not uncommon at law

firms that represented tobacco companies, lawyers at Davis Polk were permitted

to decline work on the tobacco cases if they had a moral or ethical objection to

the work, Mr. Chang said.

Asked whether Ms. Gillibrand had any misgivings about representing the tobacco

company, Mr. Canter responded by e-mail: “Senator Gillibrand worked for the

clients that were assigned to her.”

Ms. Gillibrand was never the lead lawyer on the tobacco cases, which at Davis

Polk drew on the work of dozens of lawyers and staffers. Robert B. Fiske Jr., a

former Whitewater prosecutor and a Davis Polk partner, was the top lawyer among

the approximately 20 at the firm working on the Philip Morris defense on the

perjury case. Ms. Gillibrand’s hourly rate — $305 in 1995 — put her in the

middle range of reimbursement for associates on the case, according to a tobacco

industry document.

Mr. Fiske declined, through the senator’s office, to be interviewed about her

work for Philip Morris, but released a statement calling Ms. Gillibrand “smart,

hard-working and thoughtful.”

During her most recent congressional race, Ms. Gillibrand, who is a former

smoker, accepted $18,200 in campaign donations from tobacco companies and their

executives — putting her among the top dozen House Democrats for such

contributions. Many Congressional Democrats do not accept tobacco money.

Mr. Canter said the senator should be assessed based on her record in Congress,

where she has voted against the industry’s interests on several occasions,

including supporting cigarette tax increases to help expand children’s health

care.

And Todd Henderson, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago Law

School, argued that it would be unfair to assess lawyers by whom they represent.

“Nobody would want to live in a world in which lawyers are judged by the clients

they take,” he said.

Limiting Evidence

A scion of a prominent Albany political clan, Ms Gillibrand graduated from law

school at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1991 and took a job at

Davis Polk, a firm that had worked closely with the tobacco industry for

decades.

Ms. Gillibrand was working at the firm during critical years for the tobacco

industry, as the public tide was turning against smoking, and leading Democrats

in the Clinton administration and Congress pushed for a more aggressive stance

toward cigarette companies. At the same time, plaintiffs’ lawyers were beginning

to chip away at the industry’s time-tested legal strategies.

In 1994, executives of the nation’s largest tobacco companies, including Philip

Morris, prompted anger and disbelief when they swore before Congress that they

did not believe smoking was addictive or that there was a proven link between

smoking and cancer.

That appearance intensified criticism of the industry and scrutiny by federal

prosecutors and ultimately led to a broad criminal investigation by the Justice

Department into whether the executives had perjured themselves.

The government sought reams of internal company records to determine whether the

tobacco executives had lied. There is no indication that Ms. Gillibrand ever

discussed the case with William Campbell, then the Philip Morris president and

chief executive, who was among the subjects of the perjury inquiry. But Philip

Morris internal records show that the company’s top lawyers entrusted her with

several essential elements of the case.

As a member of the Eastern District of New York Subpoena Working Group, Ms.

Gillibrand helped limit what evidence the government obtained. She also

monitored the testimony of witnesses who appeared before the grand jury and

wrote strategy memos to the Philip Morris general counsel, Ken Handal, analyzing

the witnesses’ statements and their impact on the investigation.

Her travels to Germany took her to the Institut Fur Biologische Forschung, or

Institute for Biological Research, a laboratory that Philip Morris had set up in

Cologne, which has been criticized by antitobacco activists and cancer doctors.

The establishment of the lab overseas, where topics of study included the role

of tobacco in cancerous tumors, had allowed the company to keep conducting

research there, beyond the reach of the United States government, news media and

plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Ms. Gillibrand learned so much about the laboratory’s inner workings during the

criminal investigation that by 1997, records show, she provided Philip Morris

lawyers with a list of questions about the German lab to help them prepare

company witnesses being called to testify in civil cases in Minnesota and

elsewhere across the country.

At the laboratory, she interviewed Dr. Max Reininghaus, the general manager who

oversaw the experiments, and reviewed lab personnel records that had been sought

by federal investigators.

In 1998, when the case reached a turning point as one tobacco company, the

Liggett Group, considered cooperating with prosecutors, Ms. Gillibrand was one

of a handful of lawyers for Philip Morris privy to the unsuccessful efforts to

dissuade Liggett from breaking ranks with the other cigarette makers.

She was also among the small group of Philip Morris lawyers involved in the

effort to contain the damage the defection could do to other companies in the

tobacco industry, pushing to prevent Philip Morris from disclosing any documents

that would violate the confidentiality of the other co-defendants.

“She clearly was more than a lowly associate lawyer on the case,” said Anne

Landman, a tobacco document researcher who has testified against the industry

and edits Tobaccowiki.org, a Web site that provides analysis of tobacco

documents. “Philip Morris showed deep trust in her and brought her in on

sensitive legal matters that were of great importance to the company.”

In the face of the vigorous counteroffensive from the industry, the Justice

Department abandoned its criminal inquiry in 1999 and decided to bring a

racketeering case in civil court, claiming that the cigarette companies

conspired for half a century to mislead the public about the dangers of smoking.

Ms. Gillibrand did not work on the racketeering case, on which other law firms

took the lead. But when Judge Gladys Kessler of Federal District Court handed

down her landmark decision in that case in 2006, finding that the tobacco

companies had conspired to defraud the public, she based the ruling in part on

the business practices Ms. Gillibrand had delved into during the perjury case.

The judge cited Philip Morris’s use of the German lab as a way for the company

to suppress evidence and scolded the company for concealing information from

consumers and government regulators.

Asked last week whether Ms. Gillibrand agreed with the judge’s decision, her

spokesman replied: “Senator Gillibrand did not work on that case and is not

familiar with its details.”

A Rising Star

Ms. Gillibrand was also deeply involved as Philip Morris and other cigarette

makers confronted another challenge: mounting accusations that the industry was

abusing the attorney-client privilege to prevent disclosure of damaging research

and other sensitive documents.

Legal experts and a Congressional committee said that for decades, the companies

had misused the attorney-client privilege to try to conceal scientific

information that was damaging to the industry. The lawyers, for example,

participated in overseeing scientific research projects that they could then

keep confidential. But in the 1990s, government and plaintiffs’ lawyers began

directly challenging this protection.

The state of Minnesota, as part of a lawsuit seeking to force tobacco firms to

pick up the state’s cost of treating smoking-related illnesses, objected to the

companies’ claim of attorney-client privilege, invoking what is known as the

crime-fraud exception: essentially, an assertion that the privilege did not

apply because the lawyers were being used to help the companies commit fraud. A

Minnesota judge agreed, saying that Philip Morris had engaged in an “egregious

attempt to hide information” and, in a major blow to the industry, eventually

forced the release of some 30 million pages of documents from industry files.

Philip Morris and the other companies subsequently settled the Minnesota case

for $6 billion in 1998.

But with the industry facing other lawsuits around the country, Philip Morris

turned to a committee it established to handle issues surrounding disclosure of

other documents. In some instances, the committee sought to determine if certain

documents had been improperly shielded under attorney-client privilege rule. But

the committee also worked to protect other industry documents from being

released, a practice that drew harsh criticism from lawyers and others who took

on the industry.

Clifford Douglas, who served as a lawyer for the Congressional task force that

looked into the tobacco industry’s practices, said, “The crime fraud committee

was charged with preventing plaintiffs or the government from seeing sensitive

documents that Philip Morris wanted to keep secret.”

Some of the nation’s most prominent tobacco lawyers from several prestigious law

firms had seats on the committee, known as the Philip Morris Crime Fraud Issues

Committee. And so did Ms. Gillibrand, who was already seen as a rising star

among her colleagues at Davis Polk.

Mr. Chang, who worked with her at the firm, said it was telling that Ms.

Gillibrand would be assigned to the panel along with “the linchpins of the

tobacco defense bar in the entire country.”

“That’s certainly an indicator of the kind of respect that she was accorded at

Davis Polk that they would chose her — a relatively junior associate — to be on

a panel with some of the most prominent senior tobacco lawyers in the country,”

he said.

Leslie Wharton, a senior counsel at the Washington law firm of Arnold Porter

L.L.P. and a member of the crime fraud committee, said that although Ms.

Gillibrand had less experience and stature than other lawyers on the panel, she

was assertive, deeply involved and very effective in advocating on behalf of

Philip Morris.

“She did more than pull her own weight,” Ms. Wharton said. “We handled highly

specialized issues on a whole variety of cases, and she was a full partner in

everything we did. She worked as hard as anyone and was a very capable, smart

lawyer.”

Much of the committee’s work remains sealed, but internal documents indicate

that the committee had wide latitude and “should be consulted with respect to

just about any privilege issue that might arise in any case.”

A Philip Morris spokesman declined to discuss the committee or when it was

formed.

Helping With Strategy

At Davis Polk, lawyers not only represented Philip Morris in litigation, they

advised the company on business strategy, including how to protect the image of

the cigarette company and how to deal with concerns about the effects of its

products. This approach reflects, in part, the longstanding closeness between

the firm and tobacco makers. But it also raised concerns among critics that the

lawyers had crossed a line, and were essentially becoming agents in the business

operation.

There were instances, for example, when Ms. Gillibrand was called upon to help

the company deal with mounting public unease about its product and practices,

according to interviews and a review of industry documents. Ms. Gillibrand was

also schooled in some of the chemistry of cigarettes.

In 1998, for example, Roger G. Whidden, Philip Morris’s vice president for

worldwide regulatory affairs, wrote Ms. Gillibrand a letter along with a draft

document containing proposed responses to possible questions from reporters

about nitrosamines, a cancer-causing agent in cigarettes.

In the letter, Mr. Whidden tells Ms. Gillibrand that the draft was prepared “on

the basis of conversations” with her and others at Philip Morris, and asks her

to review it. The suggested answers state that Philip Morris is working to

reduce the presence of the deadly agent in cigarette smoke.

But the document also makes an assertion that experts say is highly misleading.

The document declares flatly that the amount of nitrosamines in cigarette smoke

had been reduced through filtration. That assertion was not in keeping with what

was known about limitations of certain cigarette filters at the time, the

experts say: smokers frequently compensated for them by inhaling more deeply,

plugging up filter ventilation holes with their fingers or lips or taking more

puffs.

The tobacco companies had been aware of this flaw in the filters for decades,

according to industry documents and interviews, and Ms Gillibrand had just weeks

before been briefed on their shortcomings and had taken a tour of the filtration

section of Philip Morris’s production plant, according to company documents.

The presentation was given by Bill Dwyer, a scientist in the company’s research

and development division, who described, among other things, how plugging the

ventilation holes of filters diminishes the effectiveness of the filters.

As New Lawyer,

Senator Defended Big Tobacco, NYT, 27.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/27/nyregion/27gillibrand.html?hp

Contraception Pill Strictures

Are Eased by a Judge

March 24, 2009

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

A federal judge ordered the Food and Drug Administration on

Monday to make the Plan B morning-after birth control pill available without

prescription to women as young as 17.

The judge ruled that the agency had improperly bowed to political pressure from

the Bush administration in 2006 when it set 18 as the age limit.

The agency has 30 days to comply with the order, in which the judge also urged

the agency to consider removing all restrictions on over-the-counter sales of

Plan B. The drug consists of two pills that prevent conception if taken within

72 hours of sexual intercourse.

Some women’s health advocates hailed the decision.

“It is a complete vindication of the argument that reproductive rights advocates

have been making for years, that in the Bush administration it was politics, not

science, driving decisions around women’s health,” said Nancy Northup, president

of the Center for Reproductive Rights, the attorneys for the plaintiff in the

suit against the F.D.A.

But some conservative groups voiced concern that the ruling could promote sexual

promiscuity. “Now some minor girls will be able to obtain this drug without any

guidance from a doctor and without any parental supervision,” the Family

Research Council said in a statement.

Plan B has been available by prescription in the United States since 1999.

But because the drug must be taken so soon after intercourse to be effective, in

2001 more than five dozen public health groups, with endorsements from World

Health Organization and the American Medical Association, asked the F.D.A. to

make Plan B available over the counter.

Not until 2006 did the F.D.A. rule, saying that the drug could be sold without a

prescription only to women over 18. In order to enforce the age restriction, the

agency also ordered that Plan B be stocked behind pharmacy counters, in contrast

to other over-the-counter contraceptives like condoms.

On Monday, in a decision that criticized former F.D.A. officials, Judge Edward

R. Korman of Federal District Court in New York threw out the F.D.A. ruling.

Judge Korman wrote that officials of the agency had repeatedly delayed action on

the petition, moving only when members of Congress threatened to hold up

confirmation hearings on acting F.D.A. commissioners. Several officials also

violated the agency’s own policies, he wrote.

Citing depositions, Judge Korman wrote that agency officials had improperly

communicated with White House officials about Plan B. And, he said, F.D.A.

employees sought to influence decisions by appointing people with anti-abortion

views to an independent panel of experts reviewing Plan B for the agency.

The agency also departed from its normal procedures, the judge wrote, by

ignoring favorable conclusions about the drug by an advisory panel as well its

own scientists and officials who found that the drug could be safely used by

women at least as young as 17.

Such “political considerations, delays and implausible justifications” showed

that the F.D.A. had acted without good faith or reasoned decision making, Judge

Korman wrote.

Susan F. Wood, a former F.D.A. director of women’s health who resigned in 2005

to protest the handling of Plan B, said Monday that the judge’s decision to send

the drug back for reconsideration signaled hope of the agency’s ability to act

independently under a new administration.

There is a new chance to “restore the scientific integrity of the F.D.A.,” said

Ms. Wood, now a professor of public health at George Washington University.

In response to a query from a reporter, an F.D.A. spokeswoman wrote Monday in an

e-mail message that the agency was still reviewing the decision.

Contraception Pill

Strictures Are Eased by a Judge, NYT, 24.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/24/health/24pill.html?hp

Editorial

The Rules on Stem Cells

March 16, 2009

The New York Times

No sooner had President Obama lifted the Bush-era restrictions

on financing embryonic stem cell research than critics began urging that any

federal support be limited to work with stem cells derived from surplus embryos

at fertility clinics. That would be a mistake. The guidelines should define the

eligible research as broadly as possible to allow the greatest potential for

advances.

Some of the most important research requires stem cells genetically matched to

patients with specific diseases, such as Parkinson’s or diabetes. These can

rarely be identified in the huge stock of surplus embryos.

President Bush limited scientists to 21 stem cell lines derived from surplus

embryos before mid-2001. Congress twice passed bills to allow potentially

thousands more lines from surplus embryos to be used. Mr. Bush vetoed them.

(Hundreds of stem cell lines have been created around the world, all or

virtually all from surplus embryos.)

This single-minded focus on the surplus embryos — left over after patients’

fertility treatments were completed — was mostly because a strong moral argument

could be made that these microscopic, days-old embryos were doomed to be

discarded anyway. Why not gain potential medical benefits from studying their

stem cells?

Now President Obama seems open to the possibility of moving beyond the surplus

embryos. His announcement placed few boundaries on stem cell research beyond

requiring it to be scientifically worthy, responsibly conducted and compliant

with the law.

He gave the National Institutes of Health free rein to devise guidelines

governing what kinds of research can be supported and what ethical strictures

will be placed on it.

Let us hope that the N.I.H. broadens the range of stem cells that can be

studied.

Scientists believe that one way to obtain the matched cells needed to study

diseases is to use a cell from an adult afflicted with that disease to create a

genetically matched embryo and extract its stem cells. This approach — known as

somatic cell nuclear transfer — is difficult, and no one has yet done it.

Another approach — known as induced pluripotent stem cells — has shown that

adult skin cells can be converted back to a state resembling embryonic stem

cells without ever creating or destroying an embryo. Some experts think that

approach may be the most promising, for moral and practical reasons.

Even so, work on genetically matched embryonic stem cells would still be

important. They may be the best way to study the earliest stages of a disease,

or prove superior for other purposes. They will almost certainly be needed as a

standard to judge the value of the induced pluripotent cells.

When the N.I.H. sets the rules for federally financed research, the main

criterion should be whether a proposal has high scientific merit.

The Rules on Stem

Cells, NYT, 16.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/16/opinion/16mon1.html

Letters

Doctor-Patient-Computer Relationships

March 11, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “The Computer Will See You Now”

(Op-Ed, March 6):

Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben has provided a spot-on description of the fallibilities

of the electronic medical record from the standpoint of the doctor-patient

encounter. It can depersonalize situations that require personal interaction. To

her account, let me add one thing I’ve noticed.

All too often when taking a history, residents and attendings in a hurry will

simply use the cut-and-paste function to save time and bypass asking potentially

important questions that have been asked before. Without ever undergoing

independent verification, erroneous data from the original history gets

perpetuated. Doctors rely on others for their own versions of events, a

potential source of misinformation and error.

Cory Franklin

Wilmette, Ill., March 6, 2009

The writer is a former director of medical intensive care, Cook County Hospital,

Chicago.

•

To the Editor:

Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben presents her experience in adapting to electronic

medical records as a cautionary tale, proscribing an open embrace of the

computer in the doctor-patient relationship.

Is it too much to expect that physicians who continually educate themselves on

the latest medical treatments also integrate the latest improvements in

delivering that care? I have found that my last year with electronic medical

records in my practice has been a step forward for the health of my patients.

Maintaining the doctor-patient relationship required adaptation to technology,

not submission to it.

Jihad Shoshara

La Grange, Ill., March 6, 2009

The writer is a medical doctor.

•

To the Editor:

I must agree wholeheartedly with Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben: the presence of a

computer in the exam room is more of a detriment than an advantage.

The physician focuses on the computer and misses patient or parental body

language (I’m a pediatrician, too). Awful mistakes may get clicked and pass

unnoticed. Girls may be described as having male genitalia and vice versa.

What is most troublesome to me is that our residents — no matter how much we

grayheads or graybeards model the approach to history-taking from parents —

learn that the checklist on the computer screen is the thing to look at, and not

the living person describing their child and her problems.

Howard Fischer

Detroit, March 6, 2009

The writer is a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of

Medicine.

•

To the Editor:

I could not agree more with Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben. The computers we all use

were invented as bookkeeping machines. At this they are superb.

They are not good at shoehorning the analog world into digital format. In fact,

computers aren’t meant to help physicians; they are meant to gather data for

others at the expense of physicians’ time, attention and job performance.

I am an anesthesiologist. In the operating room, computerization is useful for

recording metrics like pulse and blood pressure. Even here, computers hijack my

attention and interfere with my job.

We can’t do two tasks at once, and computers require just that.

Michael Cox

Santa Barbara, Calif., March 6, 2009

•

To the Editor:

A mentor of mine once told a story of a patient whose son admired a certain

Russian poet. He made a notation of this in his office note.

Several years later, upon seeing this woman again, he inquired as to whether her

son “still read Pushkin.” The patient nearly fell off her chair, so taken was

she by her doctor’s recalling this seemingly trivial but meaningful fact.

I have used this anecdote repeatedly in my own career, jotting down reminders as

to my own patients’ reading proclivities and other personal miscellany. Bringing

up these tidbits at future visits is useful in creating trust between patient

and doctor.

Unfortunately, I have yet to encounter an electronic medical record system that

allows one to document the reading habits of the patient or his family members.

Ronald B. Cohen

Woodbury, N.Y., March 6, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben makes a legitimate point about computerizing

physicians’ notes. The model she describes is simply a glorified questionnaire,

similar to the one on that clipboard we’re asked to fill out in the waiting room

during our first visit. That model is neither efficient nor effective.

What could work would be to take notes as she is now doing, then scan them into

the permanent electronic record. This would achieve the accessibility of

electronic records, and the personalization she wishes to retain.

As for the illegible handwriting: That’s a product of laziness; almost anyone

can teach himself to write legibly!

Warren Bailey

Qualicum Beach, British Columbia

March 6, 2009

The writer is a retired cardiac surgeon.

•

To the Editor:

This transference from human to computer, as if the records become the human,

isn’t special to the medical profession. It exists in other professions and in

any institution where personal data are electronically gathered.

It explains how you can feel as if you barely exist when in front of a keeper of

these records, whether a doctor or a clerk at your local motor vehicle agency.

As they stare intently into their computer screens, they are looking at the real

you that exists for them, the one in the computer.

Peter Carr

Berkeley, Calif., March 6, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Dr. Anne Armstrong-Coben’s story is a cautionary tale. It illustrates why most

of the $17 billion in President Obama’s stimulus package for promoting

electronic medical records will add to the cost of care, not reduce it.

Dr. Armstrong-Coben is applying the computer to a method of pediatric practice

that has been in effect from time immemorial. The cost of computers has been

added to the cost of her practice without, it seems, improving her efficiency.

What she ought to be doing is thinking up a new, better and less expensive way

to provide health care to children that is practical only with computers and

then get someone to develop a program to support it.

Not being a pediatrician, I would not presume to suggest what that way might be,

but I’m sure that it is out there waiting to be discovered.

Richard Wittrup

Scituate, Mass., March 6, 2009

The writer is a retired hospital administrator.

Doctor-Patient-Computer Relationships, NYT, 11.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/11/opinion/l11medical.html

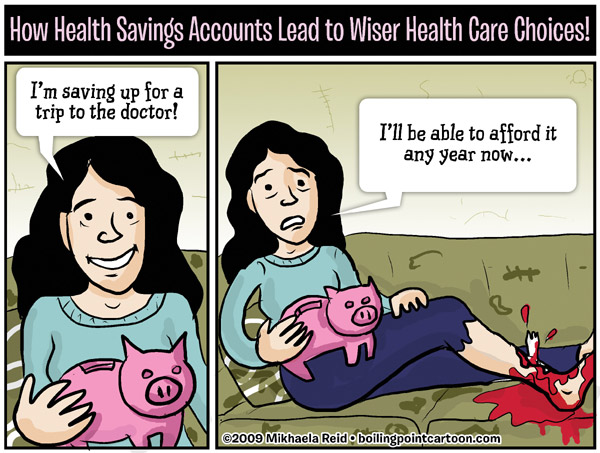

21% of Americans

scramble to pay medical, drug bills

10 March 2009

USA Today

By Liz Szabo and Julie Appleby

Denise Prosser, 39, has battled cancer since she was a

toddler.

Yet Prosser can't afford her next cancer treatment — a

radioactive therapy that she's supposed to receive once a year — because she and

her husband lost their jobs in December. Without insurance, she has postponed

the radiation indefinitely and is taking only half of her asthma medications —

sacrifices that often leave her gasping for air and could allow her cancer to

come surging back.

"I can't walk more than 100 feet without sounding like I just

ran a marathon," says Prosser, of Galloway, N.J.

Prosser is among millions of Americans who struggled last year to pay for health

care or medications, the largest poll ever conducted by Gallup shows.

As the economy fell, the percentage who reported having trouble paying for

needed health care or medicines during the previous 12 months rose from 18% in

January 2008 to 21% in December, according to the poll of 355,334 Americans.

Each percentage point change in the full survey represents about 2.2 million

people, says Jim Harter, Gallup's chief scientist for well-being and workplace

management.

Gallup, along with disease management company Healthways, surveyed a random

sample of about 1,000 people nearly every day during 2008 about their physical,

emotional and economic well-being.

The poll, the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index, shows that struggles to pay

crossed all socioeconomic lines but hit some Americans harder than others: More

than half of the uninsured had trouble paying for health care or medications

during the year. So did more than 30% of blacks and Hispanics, compared with 17%

of whites and 13% of Asians. Overall, women had more trouble than men. Those who

were divorced, widowed or in domestic partner arrangements fared less well than

those who were married.

Among other key findings:

• As the year progressed, fewer Americans reported getting health coverage

through their jobs, dropping from 59% in the first quarter to 58% by the last.

• The number of African Americans reporting trouble paying for health care or

medications rose six percentage points from the first quarter to the last, to

34%. People ages 25-34 also saw a big increase, up five points to 28%.

• Among the states, Hawaii had the smallest percentage of residents who had

trouble paying for health care in the previous 12 months at 12%, and Mississippi

the most at 29%.

"The biggest problem that the country has is actually the cost of health care,"

says Jim Clifton, Gallup's CEO. "It's a lot bigger problem than war and a bigger

problem than the current meltdown because there are no fixes to it on the

horizon right now. … You can't just throw money at it. That's still not a fix."

The increasing trouble people have paying for medical care comes as Congress

begins its most serious health care overhaul debate in 15 years — and as the

economy continues to shed jobs.

Because most people still get health insurance through their jobs — rather than

buying it themselves or being covered by a government program such as Medicare —

the loss of a job can mean the loss of insurance.

Nearly 4.4 million people have lost jobs since the recession began in December

2007, the U.S. Department of Labor reports. Nearly one in 10 children and one in

five adults under age 65 are uninsured, says a February report on the uninsured

from the Institute of Medicine, part of the National Academy of Sciences, which

advises the government on health care.

People without insurance are at much higher risk for a host of medical problems,

the institute's report shows. They're less likely to get preventive care, more

likely to be diagnosed with later-stage cancers and more likely to die if they

suffer a heart attack, stroke, lung problem, hip fracture, seizure or trauma.

"The evidence clearly shows that lack of health insurance is hazardous to one's

health," says report co-author Lawrence Lewin. "And the situation is getting

worse."

Lower-income residents are more likely to have trouble paying medical bills and

to lack insurance. Income also plays a role in how people feel about their own

physical well-being.

The Gallup-Healthways poll found that 40% of those making $500 to $1,000 a month

said they were dissatisfied with their health. By comparison, only 10% of

wealthy people — those making at least $10,000 a month — are dissatisfied with

their health.

Few safety nets

People often resort to desperate solutions to pay for health care for themselves

and their families, says Christy Schmidt, senior policy director at the American

Cancer Society's Cancer Action Network.

Some are tapping into their 401(k) plans and other retirement savings, she says.

But even these funds may fall short, since many investments have lost half their

value in the past year.

When money gets really tight, Schmidt says, many uninsured people cut corners on

their health, such as by cutting pills in half or skipping doctor's

appointments.

While Gallup's poll asked if the specific person being interviewed had cut back

on "needed" health care, a February poll by Kaiser Family Foundation took a

broader look at health care spending. In that poll, more than half of Americans

said at least one person in their family had cut back on medical care within the

previous 12 months because of cost.

Many people can't pay for coverage on their own, Schmidt says.

Among them are Denise Prosser, who worked part time in a day care before being

laid off, and her husband, Warren, who was a television news director in

Linwood, N.J.

The 600 stitches on her back testify to her long struggle with cancer. She was

first diagnosed at 18 months old. A new tumor, in her thyroid, developed when

she was 27. Her lung capacity has declined by 50% since then as her health has

deteriorated, leaving her unable to work full time.

The Prossers say they can't afford coverage through COBRA, a program that allows

workers to keep their health insurance for 18 months after they leave their

jobs, just as long as they pay 100% of the health premiums themselves.

A COBRA plan would cost the Prossers $900 a month, Denise says. With help from

the recently passed economic stimulus package, which provides a federal subsidy

worth 65% of COBRA premiums, the Prossers still would have to pay $300 a month —

an especially high price tag for people who no longer have regular salaries.

After she lost her job, Prosser applied for official status as disabled through

the Social Security Administration but was turned down: "They said I wasn't

disabled enough."

Even patients who qualify as disabled may struggle with medical bills, Schmidt

says. Most people have to wait two years after being declared disabled before

they qualify for Medicare coverage. If patients opt for 18 months of COBRA, that

still leaves a six-month gap.

That puts Prosser — whose doctor recently found a lump on her thyroid — in a

sort of no man's land.

Prosser fears the lump could be a relapse of the thyroid cancer she developed in

1997. Although her thyroid specialist gave her some free medication samples, the

doctor would not treat Prosser without insurance.

Prosser hopes to see a doctor through a charity clinic in Atlantic City but

worries her husband's income from his unemployment check — $622 a week before

taxes — may disqualify them.

A domino effect

Even charity care and emergency rooms can't guarantee that uninsured people —

especially those such as Prosser, who have a long history of complex problems —

get the treatment they need, says John Ayanian, a Harvard Medical School

professor and co-author of the Institute of Medicine report. Free clinics often

struggle just to find generalists, he says, let alone specialists.

The problem extends beyond individual struggles.

Eroding insurance coverage can undermine the health of entire communities,

Ayanian says. Hospitals and doctors may have trouble paying their own bills in

communities with large numbers of uninsured. That can drive away specialists and

make it harder for even well-insured people to find care, the report says.

Often, people without insurance must struggle on their own.

Calls to the cancer society's insurance hotline have increased by 6% since last

year, Schmidt says. Although the society sometimes can help patients find

coverage, three out of five callers find those options — such as individual

health policies or state-sponsored high-risk pools — too expensive, Schmidt

says.

Nor is there any guarantee those options will be available. Individual policies

sometimes won't cover pre-existing medical conditions, such as cancer,

depression or pregnancy, or will not pay for care needed for those conditions

during an initial period of six months or more.

Dropping insurance

Jim Hann, 51, who's losing his job as a chemical operator at the Americas

Styrenics plant in Marietta, Ohio, next month, won't be able to afford COBRA,

even with the federal subsidy. The plant is laying off 65 of 100 employees. That

didn't deter him, however, from donating a kidney to his wife, Hannah.

In the past decade, Hannah has weathered more surgeries than

they can count: seven or eight operations to cut away dying sections of bowel, a

small intestine transplant and, in February, the kidney transplant at

Washington's Georgetown University Hospital.

"He tells me he'd give me both of his if that's what it took," says Hannah, 49,

a few days after the February transplant.

Their surgeon moved up her transplant surgery by a month, before Jim's coverage

lapsed. Although Hannah's disability makes her eligible for Medicare, she has

used Jim's generous company-funded insurance until now. Medicare will cover her

health care after Jim loses his coverage in November.

Jim plans to get by without any insurance. That's a gamble, given that kidney

donors have an increased risk of high blood pressure and kidney problems.

After taking care of Hannah for so many years, Jim says he's well-prepared for

his next career.

He has decided to enroll in a nursing program that will make him a registered

nurse within two years. Until then, he says, the couple will "tough it out" by

living off their savings, Hannah's disability check and the proceeds they make

selling their home to move into a smaller, cheaper house. If needed, Jim says

he's prepared to return to driving a truck or waiting tables while going to

school.

But he doubts he'll ever find another job like the one he lost. Factories are

laying off at least 1,000 workers in the region around Marietta and Ravenswood,

W.Va., about 50 miles away, where Century Aluminum is shutting down a plant and

letting go about 600 employees.

The Gallup-Healthways survey found nearly 25% of people in the congressional

district that includes Marietta didn't have enough money to pay for health care

in the past year.

"There aren't even any bad jobs," Jim says. "It's the same all over."

Contributing: Susan Page

21% of Americans

scramble to pay medical, drug bills, UT, 10.3.2009,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2009-03-10-gallup-medical-bills_N.htm

Editorial

Science and Stem Cells

March 10, 2009

The New York Times

We welcome President Obama’s decision to lift the Bush

administration’s restrictions on federal financing for embryonic stem cell

research. His move ends a long, bleak period in which the moral objections of

religious conservatives were allowed to constrain the progress of a medically

important science.

Even with this enlightened stance, some promising stem cell research will still

be denied federal dollars. For that to change, Congress must lift a separate ban

that it has imposed every year since the mid-1990s.

Mr. Obama also pledged on Monday to base his administration’s policy decisions

on sound science, undistorted by politics or ideology. He ordered his science

office to develop a plan for all government agencies to achieve that goal.

Such a pledge should be unnecessary. Unfortunately, for eight years, former

President George W. Bush did just the opposite. He chose scientific advisory

committees based on ideology rather than expertise. His political appointees

aggressively ignored, distorted or suppressed scientific findings to promote a

political agenda or curry favor with big business.

This cynical approach seriously hampered government efforts to address global

warming and encourage sound family planning practices, among other issues.

President Obama was appropriately cautious, warning that the full promise of

stem cell research remains unknown and should not be overstated. Some of the

benefits, he said, might not appear in our lifetime or even our children’s

lifetime. But scientists hope that stem cell therapies may eventually lead to

treatments or cures for a wide range of degenerative diseases, such as

Parkinson’s and diabetes, and Mr. Obama rightly promised to pursue the research

with urgency.

In one of his first acts as president, Mr. Bush restricted federal financing for

embryonic stem cell research to what turned out to be 20 or so stem cell lines

that had been created prior to his announcement. Those lines are too limited in

number, variety and quality to allow the full range of needed research.

With the end of the Bush restrictions, scientists receiving federal money will

be able to work with hundreds of stem cell lines that have since been created —

and many more that will be created in the future. The full range of additional

research allowed won’t become apparent until new guidelines governing what

research can qualify for federal support are issued by the National Institutes

of Health.

Other important embryonic research is still being hobbled by the so-called

Dickey-Wicker amendment. The amendment, which is regularly attached to

appropriations bills for the Department of Health and Human Services, prohibits

the use of federal funds to support scientific work that involves the

destruction of human embryos (as happens when stem cells are extracted) or the

creation of embryos for research purposes.

Until that changes, scientists who want to create embryos — and extract stem

cells — matched to patients with specific diseases will have to rely on private

or state support. Such research is one promising way to learn how the diseases

develop and devise the best treatments. Congress should follow Mr. Obama’s lead

and lift this prohibition so such important work can benefit from an infusion of

federal dollars.

Science and Stem

Cells, 10.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/10/opinion/10tue1.html

Drug Investors Lose Patience

March 10, 2009

The New York Times

By ANDREW POLLACK

As merger mania plays out among the pharmaceutical giants, a different sort

of financial frenzy has seized some small, struggling drug makers. Investors are

demanding that stragglers close up shop and hand over any remaining cash.

That is what happened to one company, Avigen, after its most promising drug

failed in a clinical trial last October. Avigen said it would do what countless

other biotechnology companies had done in similar circumstances: move on to the

next product in its pipeline.

Not so fast, said its biggest shareholder, the Biotechnology Value Fund. The

fund demanded that Avigen, after 16 years of trial and error, immediately

liquidate itself and return its remaining cash to shareholders.

So much for the traditional model of patience in biotechnology investing, in

which companies may burn through more than a decade and hundreds of millions of

venture capital or shareholder dollars before reaching profitability — if they

ever get there. Now, with cash scarce, credit tight and big drug companies like

Merck intent on branching into biotechnology themselves, struggling start-ups

may no longer get second and third chances to succeed.

In at least eight cases in the last year, anxious investors have tried to block

an unsuccessful biotech company’s quest for the next blockbuster, and have

fought with management for control of the corporate carcass. The investors argue

that the remaining cash belongs to them and that they — not a losing company’s

executives — should decide how to invest it.

Some companies, including Avigen, are fighting back. “I hear that argument”

about shareholder rights, said Kenneth G. Chahine, Avigen’s chief. “But it’s

really ‘I want to raid the cash.’ We’re back to 1987 and ‘Barbarians at the

Gate.’ ”

Such battles have become much more common in recent months, as the stock market

crash has pounded the value of many biotech companies to less than the cash on

hand. When that happens, investors can realize an immediate return if the

company dissolves itself — even if some of the cash will be consumed in closing

the company.

In some cases, investors are succeeding. Under pressure from the hedge fund RA

Capital Management, for example, Northstar Neuroscience, a medical device

company in Seattle whose stroke treatment failed, is proposing to liquidate,

with shareholders receiving an estimated $1.90 to $2.10 a share in cash. The

company’s stock, which had been as low as 90 cents in November, closed at $1.90

on Monday.

Another company, Trimeris, whose only product, the AIDS drug Fuzeon, has lost

sales to newer competitors, halted research and development last year and repaid

$55 million — or $2.50 a share — to stockholders. The company continues in

business, but with few employees.

And two companies, VaxGen and NitroMed, have canceled planned reverse mergers

because of shareholder opposition. In a reverse merger, a publicly traded

company essentially cedes its cash and stock listing to a private company with

presumably better prospects.

For every Gilead Sciences, which spent $450 million over 15 years and abandoned

its original technology before becoming profitable, there have been countless

“zombies” — companies that lurch from product to product, surviving years or

even decades without ever achieving success.

One company so tarred, by one of its biggest investors, is Penwest

Pharmaceuticals.

“The company’s history is an unfortunate progression of failed development

programs,” Perceptive Advisors, an investor in the company, wrote in November to

Penwest’s board. Perceptive demanded that Penwest cease all research and

development and become a virtual company that would just collect royalties on

its one successful drug. Penwest defended its track record and said it was

sticking to its course.

Some investors say that with capital markets now so tight, the walking dead

should be buried to free up financing for more viable companies. “It’s in a time

like this that the good companies are being dragged down by the bad ones,” said

Oleg Nodelman, a portfolio manager at the Biotechnology Value Fund.

In some cases, however, the investors asking for their money back are not

long-suffering shareholders. They are speculators who bought in only after the

stock price collapsed, hoping to make a quick killing.

Tang Capital Partners, for instance, began accumulating its 14.9 percent stake

in Vanda Pharmaceuticals only after the Food and Drug Administration rejected

Vanda’s schizophrenia drug in July. Tang is now pressing for the company to

cease all operations and return cash to shareholders. Vanda’s stock is trading

at 80 cents, well below the $1.74 a share in cash it had as of Dec. 31.

Vanda says that it is still hopeful that it can get its drug approved and that

liquidation is not in the interest of all shareholders.

The Biotechnology Value Fund, often called BVF, was a longtime shareholder in

Avigen. But it sold 640,000 shares, nearly all its holdings, for about $3.95 to

$4.60 a share. The sale was near the stock’s highs for the year — in the two

months before Avigen was scheduled to announce, in October, the clinical trial

results of its drug to treat a symptom of multiple sclerosis.

After the drug failed, BVF swooped in and bought more than eight million shares,

nearly a 30 percent stake, at about 58 cents a share. That was well below

Avigen’s cash total of about $1.90 a share at the time.

BVF has made a $1-a-share tender offer for Avigen and is trying to replace the

directors. If it gains control, it could liquidate Avigen or sell it to

MediciNova, which has said it wants to buy it. Mr. Chahine, the chief of Avigen,

which is based in Alameda, Calif., said its assets might be parlayed into a deal

that would be worth more than BVF or MediciNova would pay and more than the

liquidation value. “All we’re saying is, give us an opportunity to canvass the

field, see what’s out there and bring something to the shareholders,” he said.

But Mr. Nodelman said such a process might eat up the company’s remaining cash.

“Someone’s got to police the space,” he said. “We’re making sure that the last

$50 million in the company don’t go to the bankers and the consultants and the

golden parachutes.”

BVF, which specializes in smaller biotech companies, has become the most

outspoken investor pressing for its money back. The fund, based in San

Francisco, gets about half of its capital from the Ziff family, which made its

fortune in magazine publishing.

Mr. Nodelman makes no apologies for BVF’s having bought Avigen stock again after

the collapse. The fund is also pressing for a cash-out to shareholders from

CombinatoRx. BVF has been a continuous shareholder in the company, although it

added to its stake after some CombinatoRx clinical trials failed.

CombinatoRx, whose strategy is to combine two old drugs to make one new one, has

lost $236 million since its inception in 2000. The company has about $1.45 a

share in cash, but its stock is trading for only 66 cents.

Alexis Borisy, the chief executive, said the company, based in Cambridge, Mass.,

was not ready for the grave. “We obviously think there’s a lot of upside value

in the CombinatoRx technology,” he said.

BVF and CombinatoRx are now in confidential discussions about the company’s

future.

BVF is also one of four investors, which collectively own about two-thirds of

the shares, demanding money back from Neurobiological Technologies of

Emeryville, Calif.

The company’s stroke drug is derived from the venom of the Malayan pit viper.

Three of the investors, including BVF, were shareholders when that drug failed

in a clinical trial in December. The fourth bought in after the failure. The

stock now trades at 58 cents, but its liquidation value would be as high as $1 a

share.

Matthew Loar, the chief financial officer, said the company was sympathetic to

the requests but had not yet decided what to do. In any case, he said, it could

not act as fast as the investors want.

“You can’t just turn off the lights in a company in a day,” he said. Among other

things, the company must figure out what to do with 1,000 poisonous snakes, he

said. “We’re going to get rid of them in the most expeditious, reasonable way

possible.”

Drug Investors Lose

Patience, NYT, 10.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/10/business/10biocash.html

Letters

An Ethics Debate at Harvard Med

March 9, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Patching a Wound:

Working to End Conflicts at Harvard Medical” (Business Day, March 3):

Bravo to the Harvard medical students who are questioning medicine’s too-close

links to the pharmaceutical industry. It has been well demonstrated that the

outcome of research is often altered by the source of financing, even if the

researchers’ motives are pure.

The idealism of these young medical trainees should be heeded and acted upon,

especially as many of them may be the medical leaders of the future. A more

regulated and transparent approach would help restore integrity and trust to

modern medicine.

Steve Heilig

San Francisco, March 4, 2009

The writer is co-editor of The Cambridge Quarterly of Health Care Ethics.

•

To the Editor:

As a physician-scientist completing his training at a hospital affiliated with

Harvard Medical School, I can verify that the complex relationships between

medical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry can be fraught with conflicts of

interest. But I take issue with the implicit assumption that faculty members who

accept drug money are driven exclusively by greed; this issue is much more

complicated than it may seem at first.

Harvard Medical School’s “drug money” problem relates, in part, to a

little-known fact: Harvard rarely pays the salaries of its medical faculty

directly. Despite substantial revenue from tuition, most faculty members teach

medical students on a volunteer basis.

Similarly, the salaries of research faculty are not paid by Harvard, but rather

by grants from the National Institutes of Health, private foundations and in

some instances, grants from pharmaceutical companies. If these financing sources

dry up, professors are often forced to find a new job.

Thus, in many cases, money from the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t increase the

take-home pay of Harvard professors; it simply allows them to maintain their

employment.

Daniel Becker

Brookline, Mass., March 4, 2009

The writer is a fellow in the Renal Division of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and

a clinical fellow in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

•

To the Editor:

Your article implies that the “more than 200 Harvard Medical School students and

sympathetic faculty, intent on exposing and curtailing the industry influence in

their classrooms and laboratories,” are in complete agreement that industry and

private affiliation are detrimental to academic medical research. Rather, the

large number of students referred to signed a petition that advocated disclosure

of industry ties, not further severance of industry relations.

In fact, both “rival factions,” as the article described them, agree that

disclosure is important, but so are the relationships that foster quality

research, new medicines and appropriate compensation for expertise.

The implication that some Harvard physicians and researchers abuse their

academic posts for purely financial gains is unfounded. Many work tirelessly to

advance science and spend years with little compensation developing marketable

expertise in the clinic and the laboratory.

For example, in a course-based clinic centered on multiple myeloma treatment at

the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, we have seen firsthand how dramatic

improvements have been achieved through productive partnerships between academia

and industry.

Many of these researchers and physicians have given up potentially lucrative

careers in private practice or applied science to work in academia because of

their passion to educate future clinicians. Most work tirelessly to improve

patient care, advance their fields and collaborate on new treatment

possibilities.

As future physicians, we feel that disclosure of financial conflicts of interest

is essential to protecting our patients and that accurate information is

axiomatic to any medical curriculum. Our faculty, administration and students

operate within an institution that we believe provides superb patient care

through innovation, research and integrity.

Charles William Carspecken

Taylor Lloyd, Melina Marmarelis

Brian Thomas Kalish

Ashley R. Kochanek

Tomasz Stryjewski

Boston, March 4, 2009

The writers are members of the class of 2012 at Harvard Medical School.

•

To the Editor:

As a 1959 graduate of Harvard Medical School, looking forward three months to

the 50th reunion of my class, I am embarrassed to learn that my alma mater has

received an F grade from the American Medical Student Association for its poor

monitoring and controlling of drug industry money.

It is shocking that both the former dean and at least one current professor at

Harvard Medical School have served concurrently as highly paid board members of

pharmaceutical and medical products companies, and that, until recently,

professors have been allowed to serve, without disclosure in many cases, as

consultants to the manufacturers of the very products about which they teach.

Their students, many of whom will become the next generation of leaders in

American medicine, are being critically deprived of objective teaching. I am

afraid that their future patients will suffer.

The only good news in the article is that a start has been made at reform. I

hope that my reunion class will nudge this commendable effort along.

Cavin P. Leeman

New York, March 3, 2009

The writer is an emeritus clinical professor of psychiatry at SUNY Downstate

Medical Center.

An Ethics Debate at

Harvard Med, NYT, 9.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/09/opinion/l09harvard.html

Patient Money

Hanging On to Health Coverage,

if the Job Goes Away

March 7, 2009

The New York Times

By WALECIA KONRAD

If you’re fortunate to still have your job, but aren’t sure how much longer

that will be the case, lost income may not be your only worry. Your medical

insurance is at risk, too.

“When you’re still on the job, even if it’s just for a little while longer,

you’re in a slightly better position to make the most of the benefits you have

now and to figure out your options,” said the Oklahoma insurance commissioner,

Kim Holland, a longtime promoter of affordable health insurance.

She and other experts offer the following advice about girding for the worst

case.

Use it before you lose it. “My clients wouldn’t want to hear me say this,” said

Tom Billet, a senior executive with the corporate benefits consulting firm

Watson Wyatt. “But if you feel a layoff is pending, now is the time for you and

your family to get physicals, dental check-ups, eye exams and prescriptions

filled.”

That’s what Denise Young Farrell is doing. Ms. Farrell, the mother of two

children in Park Slope, Brooklyn, lost her job early this year when her

department at the Lifetime Networks cable channel moved to California. Her

husband lost his job at Bear Stearns last year. Ms. Farrell’s severance package

included two months of paid health care.

Check your benefits handbook to see how long your health care coverage will last

if you do lose your job. Often, employers will continue coverage until the last

day of the month in which the employee worked. So if your last day at work was

March 5, for example, you may have coverage until March 31, giving you a few

extra days for those doctor visits.

Sign onto your spouse’s plan. If your spouse has employer-sponsored family

health insurance benefits, he or she can add you and your dependents anytime

during the year. But do be aware of the deadlines. Most companies require any

changes to be filed within 30 or 60 days of the “qualifying event.” Depending on

your spouse’s company, that could mean the day you were laid off or your last

day of coverage.

In addition, some companies require written proof from your former employer that

you were laid off. To avoid snags, try to arrange this before your last day of

work. And be sure to check when the new coverage takes effect. If your spouse’s

plan has a three-month waiting period, for example, you’ll need to find

temporary coverage elsewhere.

Get to know Cobra. If you have health benefits in your current job, odds are

you’ll be eligible to continue purchasing that coverage temporarily under the

1986 law known by its acronym, Cobra.

Cobra requires employers with 20 or more workers to make health insurance

available to a former employee for up to 18 months after leaving the job —

regardless of whether you quit or were laid off. But because the former worker

must pay the full cost of that insurance, the premiums can easily exceed $1,000

a month for family coverage.

The new federal stimulus plan that President Obama recently signed into law does

provide some temporary relief for laid-off workers. But even if you qualify for

the subsidy, you’ll still pay 35 percent of the total health premium, compared

to the 10 or 15 percent you paid as an employee. So you might be paying $300 to

$400 or more a month. And that is for only the first 9 months of the 18-month

Cobra coverage. For the second nine months you’ll be paying full fare.

For fuller details on the new Cobra provisions, see this Congressional Web

page.If you do choose Cobra, pace yourself. Time it right, and you can

essentially get two months of free Cobra coverage.

After your last day of coverage under your employer’s plan, you have 63 days to

sign up to extend that coverage under Cobra. If you think you’re on the verge of

getting a new job, or if you’re trying to find a more affordable insurance

option, you can put off paying two months of Cobra premiums until you approach

the deadline. If the new job or alternate insurance works out, you will have

avoided those hundreds of dollars in Cobra premiums. But if you do fall ill or

get in an accident in the interim, you will be covered — as long as you pay

those back premiums.

Do be vigilant, though, about that 63-day deadline. Miss it, and you lose your

Cobra eligibility.

Try to negotiate health care as part of your severance. If you are eligible for

any type of severance, consider asking for an extension of health insurance in

exchange for a smaller cash payout. That will give you more time to research

your health insurance options and help you avoid a gap in coverage.

There is one caveat, said Kathryn Bakich, national health care compliance

director for the Segal Company, a benefits consulting firm: Avoid having your

company pay part or all of your Cobra premiums as part of a severance agreement.

Employers are still waiting for guidance on this point from the Department of

Labor and other government agencies, but if your former employer pays your Cobra

premiums directly, you may be ineligible for the new Cobra subsidy, according to

Ms. Bakich and other benefits experts. You’d be better off trying get a lump sum

payment that you could use to pay Cobra premiums, if extending your current

coverage isn’t an option.

When Cobra is not an option ... If you work for a small company (fewer than 20

employees) that doesn’t offer Cobra, 40 states offer what’s called mini-Cobra

continuation coverage that allows you to stay in your group plan. Some states

may offer the new Cobra subsidy in these plans. (Check with your state’s

insurance department.) If you do not have access to Cobra or a state

continuation plan, or if those benefits are close to running out, it’s important

to find insurance of some kind, whether it is group or individual.

Federal law mandates that at least one nongroup insurer in your state must

provide coverage to everyone, regardless of health issues. In many cases this is

your state’s high-risk insurance pool, but there are no limits on how much

insurers can charge for this coverage, so premiums can be extremely expensive.

For more information on what your state offers, go to the National Association

of Insurance Commissioners’ Web site, naic.org, to link to your state’s

insurance department.

If you have a flexible spending account — use it. Here’s a little known bonus in

the employee’s favor:

Let’s say you signed up to contribute $1,000 this year through payroll

deductions to your health care flexible spending account. So far you’ve only put

in about $200. No matter. “Companies must still reimburse you for the full

amount you’ve elected even if you haven’t contributed the total to the account

yet,” Mr. Billet said.

In this example, if you file claims for $1,000 of eligible health care expenses

before your last day on the job, you will get the full reimbursement — not just

the $200 you’ve paid in.

Hanging On to Health

Coverage, if the Job Goes Away, NYT, 7.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/07/health/policy/07patient.html?hp

Graham Roumieu

The Computer Will See You Now

NYT

6.3.2009

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/06/opinion/06coben.html?ref=opinion

Op-Ed Contributor

The Computer Will

See You Now

March 6, 2009

The New York Times

By ANNE ARMSTRONG-COBEN

FOR 20 years, I practiced pediatric medicine with a “paper

chart.” I would sit with my young patients and their families, chart in my lap,

making eye contact and listening to their stories. I could take patients’

histories in the order they wanted to tell them or as I wanted to ask. I could

draw pictures of birthmarks, rashes or injuries. I loved how patients could

participate in their own charts — illustrating their cognitive development as

they went from showing me how they could draw a line at age 2 and a circle at 3

to proudly writing their names at 5.

Now that I’ve been using a computer to keep patient records — a practice that I

once looked forward to — my participation with patients too often consists of

keeping them away from the keyboard while I’m working, for fear they’ll push a

button that implodes all that I have just documented.

We have all heard about the wonderful ways in which electronic medical records

are supposed to transform our broken health care system — by eradicating

illegible handwriting and enabling doctors to share patients’ records with one

another more easily. The recently passed federal stimulus package provides

doctors and hospitals with $17 billion worth of incentive payments to switch to

electronic records. The benefits may be real, but we should not sacrifice too

much for them.

The problem is not just with pediatrics. Doctors in every specialty struggle

daily to figure out a way to keep the computer from interfering with what should