|

History > 2009 > USA > Education (I)

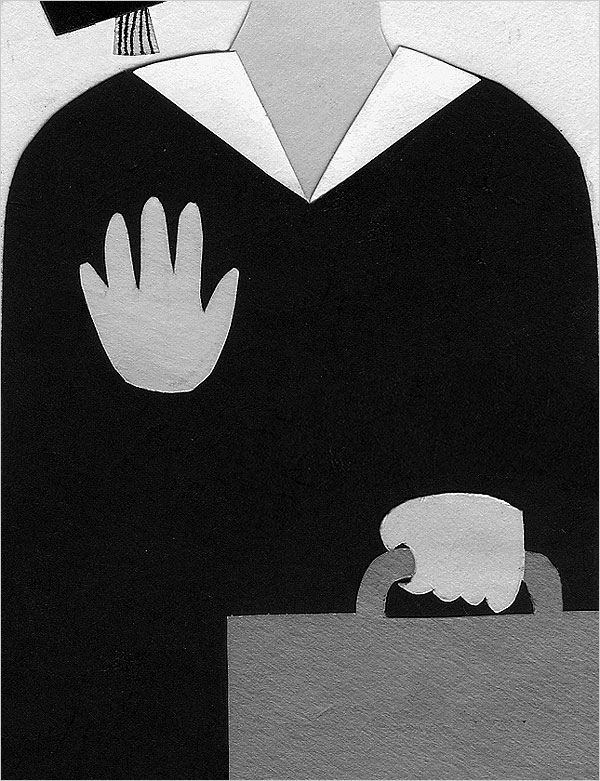

Illustration:

Morgan Elliott

The M.B.A.’s Oath: I Promise to Be Good. Honest

NYT

4.6.2009

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/

opinion/l05mba.html

Letters

Better Schools?

Here Are Some Ideas

June 14, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Five Ways to Fix America’s Schools” (Op-Ed, June 8):

Harold O. Levy proposed five ways to improve higher education, particularly

through cutting high school dropout rates, increasing college attendance and

reducing the need for remedial education. He didn’t include one of the most

powerful ways to accomplish this: raising the quality of our high school teacher

corps.

Study after study shows that the most potent school-based intervention in

raising student graduation rates and academic achievement is strong teachers. So

instead of adopting the advertising lessons of for-profit higher education, as

Mr. Levy suggests, it might be more helpful to invest in raising teacher

salaries, which would attract the highest-performing students — currently

applying to Teach for America in legions — to careers in teaching.

It would also be helpful if unions worked with school systems to make it easier

to remove failing teachers. Rather than create online teacher preparation

programs, it would be desirable to make teacher education more rigorous, base it

in public schools and strengthen teachers’ knowledge of their subject matter.

By raising the quality of our teacher force and strengthening teacher

preparation, we would certainly increase high school graduation rates, improve

students’ academic achievement and raise college attendance rates.

Arthur Levine

Princeton, N.J., June 8, 2009

The writer, president of the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, is

president emeritus of Teachers College, Columbia University.

•

To the Editor:

Harold O. Levy’s first three proposals call for external force, pressure and

inducement to get students to spend more time in school. He recommends an

extension of compulsory schooling up to age 19 (with longer days and school

years), “high-pressure sales tactics” (that can “overwhelm the consumer’s will”)

to curb truancy, and aggressive advertising to spur college enrollment.

Nowhere does he mention students’ experience of schooling, including the

likelihood that more time in today’s test-driven institutions will further

deaden their enthusiasm for learning.

America’s schools won’t improve by simply demanding or coaxing students to spend

more time in them. We must, instead, heed great educational and cognitive

scholars like John Dewey, Maria Montessori and Jean Piaget and make students’

curiosity and inner urge to learn the centerpiece of educational reform.

William Crain

New York, June 8, 2009

The writer is a professor of psychology at City College, CUNY.

•

To the Editor:

I was frustrated by Harold O. Levy’s suggestions as to how to “fix” our public

education system. He misses the core issue completely. It does not involve

branding, longer compulsory education or high-pressure “sales” tactics. Rather,

students have expressed a need to possess a coherent and integrated meaning for

the very education we are transmitting.

With the economy in a state of disequilibrium, with very few career paths

offering any guarantees, and with no coherent explanation of “What’s this all

about?,” adults should instead be challenged to seek out meaning and wisdom by

which to integrate the educational process.

Educators around the world and I have applied what is known as integral

education methods whereby we can create a neutral framework into which we place

every aspect of every subject so that both we and our students understand how

they relate to and fit with other parts of their education.

Only if we come to understand why we are doing what we are doing in the

classroom every day will our students care about what they are doing and care

enough to stay the course to graduation.

Lynne D. Feldman

Upper Saddle River, N.J.

June 8, 2009

The writer is a retired teacher.

•

To the Editor:

Harold O. Levy suggested five disparate ways to improve the educational system

in America’s schools. Only one of his suggestions, however, even remotely

touched on the most fundamental aspect of this daunting challenge: improving our

youngest students’ reading skills as a means of instilling self-confidence and

an interest in learning.

This is something that can be addressed now, without the major financing and

structural changes needed to truly reform the system.

The involvement of parents, teachers, volunteers and organizations focused on

this specific task can, and should, be emphasized and developed during the years

it will take to achieve Mr. Levy’s other objectives.

Robert Dinerstein

New York, June 10, 2009

The writer is chairman of Everybody Wins!, a nonprofit literacy and mentoring

organization.

•

To the Editor:

Many parents of bright students are horrified at the thought of extending the

school day. For bright students, learning doesn’t “end at 3 p.m.” To the

contrary, it only starts when they’re released from classrooms where they’re

forced to sit through rote lessons aimed at bringing struggling classmates up to

“proficiency.”

An alternative suggestion: Allow advanced learners to leave school an hour

early, providing them the time they’re not getting during the day to develop

their abilities and work on appropriately challenging material. This would also

allow teachers to give more individualized attention to the struggling students

remaining in the classroom. Win-win.

Susan Goodkin

Executive Director

California Learning Strategies Center

Ventura, Calif., June 8, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Harold O. Levy’s proposal leaves out essential considerations for improving the

educational process. Perhaps a better approach for reducing truancy than the

proposal for using “high-pressure sales tactics” is to examine the quality and

relevancy of instruction in schools that have high rates of truancy.

Mr. Levy mentions President Obama’s calling for parents to get more involved in

their children’s studies. In fact, many parents get involved. Identifying the

socioeconomic conditions that uninvolved parents face should lead us to conceive

of the educational process as extending far beyond formal schooling and taking

into account institutions and cultural dynamics that function as strategic

barriers to more effective schools.

To put the matter more plainly, let us be reminded that poverty is an

educational process. Jobs for all at living wages, please.

Richard La Brecque

Bradenton, Fla., June 8, 2009

The writer is professor emeritus of policy studies in education, University of

Kentucky.

•

To the Editor:

Harold O. Levy’s proposal of longer mandatory schooling guarantees the issuance

of additional diplomas without improving their woeful state. Such requirements

measure “time in seat” without addressing the root problem that educated minds

are not assembly-line products our schools try to manufacture.

Students would be better served by dismantling the one-size-fits-all high

school. Charter schools and vouchers are the best available tools to encourage

multiple methods and curriculums to meet students’ disparate needs. There are

many causes of America’s educational problems, but providing more parents with

options currently limited to the affluent can only help.

Philip Stanton

Champaign, Ill., June 8, 2009

•

To the Editor:

Harold O. Levy’s plan was based on the old formula of spending more while doing

more of the same. He doesn’t adequately address some of the fundamental concerns

affecting education.

His suggestion that students stay in school longer does nothing to help the

7,000 students who drop out daily. Hiring more truant officers to put pressure

on those not attending school doesn’t address the reasons for their not coming.

Perhaps the curriculum is not relevant, engaging or challenging.

Public school teachers are forced by federal and state laws to follow a basic

curriculum that emphasizes test scores rather than real learning.

Colleges need to work with school districts in attracting their best students to

their campuses. While Mr. Levy’s article does bring an important issue to the

forefront, his solution to a complex problem is overly simplistic.

Philip S. Cicero

North Bellmore, N.Y., June 9, 2009

The writer, a retired superintendent of schools, is an adjunct professor of

education at Adelphi University.

Better Schools? Here Are

Some Ideas, NYT, 14.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/14/opinion/l14college.html?hpw

Debate Erupts Over Muslim School in Virginia

June 11, 2009

The New York Times

By THEO EMERY

FAIRFAX, Va. — For years, children’s voices rang out from the playground at

the Islamic Saudi Academy in this heavily wooded community about 20 miles west

of Washington. But for the last year the campus has been silent as academy

officials seek county permission to erect a new classroom building and move

hundreds of students from a sister campus on the other end of Fairfax County.

The proposal from the academy, which a school spokeswoman said was the only

school financed by the Saudi government in the United States, has ignited a

noisy debate and exposed anew the school’s uneasy relationship with its

neighbors.

Many residents living near the 34-acre campus along Popes Head Road, a narrow

byway connecting two busy thoroughfares, say they oppose it because they fear it

will bring more cars, school buses and flooding of land that would be paved over

for parking lots.

But others object to the academy’s curriculum, saying it espouses a

fundamentalist interpretation of Islam known as Wahhabism. A leaflet slipped

into mailboxes in early spring called the school “a hate training academy.”

James Lafferty, chairman of a loose coalition of individuals and groups opposed

to the school, said that its teachings sow intolerance, and that it should not

be allowed to exist, let alone expand.

“We feel that it is in reality a madrassa, a training place for young

impressionable Muslim students in some of the most extreme and most fanatical

teachings of Islam,” Mr. Lafferty said. “That concerns us greatly.”

School officials and parents say they are bewildered and frustrated by such

claims. The academy is no different from other religious schools, they say, and

educates model students who go on to top schools, teaches Arabic to American

soldiers, and no longer uses texts that drew criticism after the Sept. 11

terrorist attacks.

Kamal S. Suliman, 46, a state traffic engineer with three daughters at the

academy, called the accusations “fear tactics and stereotyping.”

“Ideological issues do not belong in this matter,” Mr. Suliman said. “I’m hoping

that cooler heads will prevail,” and that a decision about the expansion “will

be made based on facts.”

The Fairfax County Planning Commission is to vote Thursday on the school’s

request for a zoning exemption to allow construction of the classroom building.

Regardless of the outcome, the request is voted on by the county Board of

Supervisors.

Hazel Rathbun, who has lived near the Fairfax campus since 1971, said she

worries about traffic safety and flooding on her winding road, and called

criticism of the school’s Muslim focus “hate filled” and irrelevant. “It’s

detracting from what we see as a very real issue for us,” Ms. Rathbun said.

The Saudi government bought the property, formerly the site of a Christian

academy, in 1984. It also rents a county school building in Alexandria.

In the 1990s, the academy bought property in Loudoun County, about 25 miles

northwest of Fairfax. Over the protest of local residents, they planned a campus

for 3,500 students through grade 12, but they scrapped the plan in 2004. They

decided to build instead on the Popes Head Road site, where classes were held

for youngsters from pre-kindergarten through first grade.

In 2007, the academy notified the county of its building plans, and last year,

transferred the young pupils to the rented building in Alexandria. Academy

officials hope to consolidate both campuses into a “state-of-the-art” school in

Fairfax, said Abdulrahman R. Alghofaili, the school’s director general.

Until Sept. 11, 2001, the academy drew minimal attention, but shortly after the

terrorist attacks, Israel turned away two graduates over suspicions they were

suicide bombers. One was charged with lying on his passport application, and

received a four-month prison sentence.

In 2003, the academy’s 1999 valedictorian, Ahmed Omar Abu Ali, was arrested in

Saudi Arabia, where he had gone to study, and two years later was convicted in

Federal District Court in Alexandria of conspiracy to commit terrorism,

including a plot to assassinate President George W. Bush. He was sentenced to 30

years in prison.

Mr. Abu Ali’s family called the accusations “lies,” and his lawyers say he was

tortured when he was held in Saudi Arabia.

Besides, academy officials and parents contend, an entire school should not be

condemned for the actions of one or two students. They point out that no one

laid the blame for the massacre at Virginia Tech on the high school alma mater

of the gunman, Seung-Hui Cho.

Last year, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, an

independent, bipartisan federal agency charged with promoting religious freedom

in United States foreign policy, concluded that texts used at the school

contained “exhortations to violence” and intolerance.

School officials rejected those findings, saying the commission misinterpreted

and mistranslated outdated materials. The school now prints its own materials

and no longer uses official Saudi curriculum, said Rahima Abdullah, the

academy’s education director.

“We have hundreds of students and hundreds of parents who send their students to

this place to get ideal education,” said Mr. Alghofaili, the director general.

“It doesn’t make sense that their parents would send their kids to a place to

learn how to hate or to kill others.”

The Fairfax Planning Commission chairman, Peter Murphy, said questions about

religion, politics and diplomacy were “distractions” that did not belong in

deliberations about whether the academy should be allowed to expand.

“Whatever happens, some people are going to be happy and some people are not

going to be happy” with Thursday’s vote, Mr. Murphy said. “I’m not basing this

on happiness. I’m basing it on land-use issues.”

Debate Erupts Over

Muslim School in Virginia, NYT, 11.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/11/us/11fairfax.html?hp

College in Need Closes a Door to Needy Students

June 10, 2009

The New York Times

By JONATHAN D. GLATER

PORTLAND, Ore. — The admissions team at Reed College, known for its

free-spirited students, learned in March that the prospective freshman class it

had so carefully composed after weeks of reviewing essays, scores and

recommendations was unworkable.

Money was the problem. Too many of the students needed financial aid, and the

college did not have enough. So the director of financial aid gave the team

another task: drop more than 100 needy students before sending out acceptances,

and substitute those who could pay full freight.

The whole idea of excluding a student simply because of money clashed with the

college’s ideals, Leslie Limper, the aid director, acknowledged. “None of us are

very happy,” she said, adding that Reed did not strike anyone from its list last

year and that never before had it needed to weed out so many worthy students.

“Sometimes I wonder why I’m still doing this.”

That decision was one of several agonizing ones for this small private college,

celebrated for its combination of academic rigor and a laid-back approach to

education that once attracted Steven P. Jobs, the chief executive of Apple, to

study on its leafy campus minutes from downtown.

With their endowments ravaged by the financial markets and more students

clamoring for assistance, private colleges like Reed are making numerous changes

this year in staff, students, tuition and classes that they hope will tide them

over without harming their reputations or their educational goals.

Reed and others have admitted more students to bolster revenue with larger

classes. Many are cutting costs by freezing or reducing salaries, suspending

hiring and postponing building maintenance and construction. And the cost of

attendance is rising; in Reed’s case, by 3.8 percent, to nearly $50,000 a year

for its 1,300 students.

But Reed has put off drastic measures like spending more of its endowment,

closing some departments or selling some real estate near campus. Instead,

college officials are counting on the economy to turn around quickly, as became

apparent when they allowed a New York Times reporter to sit in on budget

discussions this spring.

“Like everybody, we are trying to start by trying to cut the stuff that is least

likely to inflict real pain on the program,” said Colin Diver, Reed’s president.

When he talks about Reed’s short-term response to the recession, Mr. Diver

concedes he is torn, wondering whether a broader reassessment would be in order.

Perhaps it would be a good thing, he said, if the recession could refocus

college administrators on the quality of higher education, rather than on

investments in climbing walls (Reed does not have one) and other “country club”

aspects of college life that have fueled an academic arms race reliant on

tuition increases and fund-raising.

“The catering to consumer tastes — I keep trying to say, we are in the education

business,” Mr. Diver said, describing the pressure to keep up with wealthier

colleges and expressing a frustration rarely voiced publicly by college

presidents. “The whole principle behind higher education is, we know something

that you don’t. Therefore, we shouldn’t cater to them.”

But no college president wants to be first to make major changes in the college

experience; Reed, for example, is not abandoning plans for a new performing arts

center. “If we’re going to change our ways, we’re really going to need to be

pushed,” Mr. Diver said, referring to colleges generally. “It’s not going to

well up from within.”

So for now, the changes are modest and nearly invisible to students. The impact

is mostly in the composition of the student body over the next four years.

Reed has for now cast aside its hopes of accepting students based purely on

merit, without regard to wealth, and still meeting their financial need. Only

the nation’s richest colleges do that. What’s more, when Reed turned to its

waiting list this year, it tapped only students who could pay their way.

This year, the financial aid office put together its own, separate wait list for

students whose circumstances had changed or whose financial requests were

incomplete. Though Reed had pruned its admissions list for financial reasons

before, it always found a way to help the few students with unexpected setbacks.

This year, dozens of requests came in. Only a few got extra.

“We had so many of these people,” Ms. Limper said, “we had to say, oh my

goodness, we can’t offer aid to everyone who needs it.”

Hannah C. Moser, 17, needed financial help; her father is a paramedic, her

mother is ill and her parents are divorcing. Thrilled with the small classes and

quirky students, she applied to Reed last fall and was ecstatic when she learned

she was admitted — through an informal announcement that came in haikus by

e-mail.

But she said she qualified for only $14,000 in aid, far less than any other

college offered. She later discovered that she had not sent in a required form.

She was placed on the aid wait list, to no avail. This fall, she will enroll at

Willamette University in Salem, Ore., not too far from her hometown,

Sedro-Woolley, Wash.

“I’ve actually struggled pretty bad with not being able to go to Reed, just

because it was my reach school and everything about it was perfect and I

impossibly got in,” said Ms. Moser, an aspiring writer. “And then I couldn’t

go.”

This year, there was a 23 percent increase in freshmen seeking financial aid,

and twice as many students have appealed their aid packages, said Ms. Limper,

the aid director. “We have established some pretty stringent guidelines,” she

said, first trying to help “the people with changed circumstances.”

Those guidelines have given priority to students already enrolled like Becca

Roberts, a 19-year-old from Los Angeles whose mother lost her job at a film

distribution company last fall.

“It was sort of unforeseen,” Ms. Roberts said, “because the company seemed to be

doing very well.” She feared she would be unable to return in the spring. When

her mother called the college to describe their plight, Reed came up with more

aid, thanks to the president’s discretionary fund. For the second semester, Ms.

Roberts started work as a photographer for the college, watched her spending,

stuck to the dining hall and tried not to venture off campus.

As job losses mount, more students like her may plead for help next year. But

Ms. Limper does not expect to find money again. The budget, she said, is too

tight.

When members of Reed’s board met in February and April to hammer out the budget,

their priority was protecting the character of the college. Most of the members

are alumni, with fond memories of earnest dialogue with professors in small

groups, sometimes outside on the grass.

None of the options were appealing. Admitting more students would raise the

student-faculty ratio, a measure of academic quality and, at Reed, a sign of the

importance of interaction with professors. Raising tuition and fees would add to

pressure on already-struggling families. Cutting spending could make it harder

to recruit faculty members and could limit student resources.

Dipping further into the endowment, which provides about 20 percent of Reed’s

budget, could imperil the college’s long-term survival. Last year, the endowment

fell by nearly 25 percent, to $357 million, from $470 million. At a meeting with

the budget committee of Reed’s board, Mr. Diver said he was reluctant to tap

more of the fund: “I’m not proposing that.”

Members of the board did not push back at the time. But afterward, Daniel

Greenberg, a Los Angeles businessman who is the group’s chairman, said he was

not sure that the endowment should be off limits. “If we need to basically

depend on the endowment, let’s increase the take rate,” he said, referring to

the percentage of the endowment spent by the college every year. “We should do

it if it will protect the character of the college.”

Instead, the board has approved increases in tuition and fees that bring the

total cost of a year at Reed to $49,950. The college will have nearly 400 new

first-year and transfer students in the fall, up from 355 last year.

Reed has increased its financial aid budget by 7.8 percent. It aims to use part

of the $200 million it hopes to raise in a capital campaign, announced this

spring, for financial aid in future years.

The college has cut 5 percent of its spending except on personnel. It has

avoided layoffs — unlike some other institutions — though it is not filling

vacancies.

Like many colleges, Reed is betting on a quick recovery of the economy and the

financial markets to fuel endowment growth of 10 percent annually — including

investment returns and gifts — beginning next year.

Asked by a board member what would happen if those assumptions did not pan out,

the college’s treasurer, Edwin O. McFarlane, was blunt: “We’ll have to revisit

the whole ballgame.”

College in Need Closes a

Door to Needy Students, NYT, 10.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/10/business/economy/10reed.html?hpw

18 and Under

At Last, Facing Down Bullies (and Their Enablers)

June 9, 2009

The New York Times

By PERRI KLASS, M.D.

Back in the 1990s, I did a physical on a boy in fifth or sixth grade at a

Boston public school. I asked him his favorite subject: definitely science; he

had won a prize in a science fair, and was to go on and compete in a multischool

fair.

The problem was, there were some kids at school who were picking on him every

day about winning the science fair; he was getting teased and jostled and even,

occasionally, beaten up. His mother shook her head and wondered aloud whether

life would be easier if he just let the science fair thing drop.

Bullying elicits strong and highly personal reactions; I remember my own sense

of outrage and identification. Here was a highly intelligent child, a lover of

science, possibly a future (fill in your favorite genius), tormented by brutes.

Here’s what I did for my patient: I advised his mother to call the teacher and

complain, and I encouraged him to pursue his love of science.

And here are three things I now know I should have done: I didn’t tell the

mother that bullying can be prevented, and that it’s up to the school. I didn’t

call the principal or suggest that the mother do so. And I didn’t give even a

moment’s thought to the bullies, and what their lifetime prognosis might be.

In recent years, pediatricians and researchers in this country have been giving

bullies and their victims the attention they have long deserved — and have long

received in Europe. We’ve gotten past the “kids will be kids” notion that

bullying is a normal part of childhood or the prelude to a successful life

strategy. Research has described long-term risks — not just to victims, who may

be more likely than their peers to experience depression and suicidal thoughts,

but to the bullies themselves, who are less likely to finish school or hold down

a job.

Next month, the American Academy of Pediatrics will publish the new version of

an official policy statement on the pediatrician’s role in preventing youth

violence. For the first time, it will have a section on bullying — including a

recommendation that schools adopt a prevention model developed by Dan Olweus, a

research professor of psychology at the University of Bergen, Norway, who first

began studying the phenomenon of school bullying in Scandinavia in the 1970s.

The programs, he said, “work at the school level and the classroom level and at

the individual level; they combine preventive programs and directly addressing

children who are involved or identified as bullies or victims or both.”

Dr. Robert Sege, chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Boston Medical Center and a

lead author of the new policy statement, says the Olweus approach focuses

attention on the largest group of children, the bystanders. “Olweus’s genius,”

he said, “is that he manages to turn the school situation around so the other

kids realize that the bully is someone who has a problem managing his or her

behavior, and the victim is someone they can protect.”

The other lead author, Dr. Joseph Wright, senior vice president at Children’s

National Medical Center in Washington and the chairman of the pediatrics

academy’s committee on violence prevention, notes that a quarter of all children

report that they have been involved in bullying, either as bullies or as

victims. Protecting children from intentional injury is a central task of

pediatricians, he said, and “bullying prevention is a subset of that activity.”

By definition, bullying involves repetition; a child is repeatedly the target of

taunts or physical attacks — or, in the case of so-called indirect bullying

(more common among girls), rumors and social exclusion. For a successful

anti-bullying program, the school needs to survey the children and find out the

details — where it happens, when it happens.

Structural changes can address those vulnerable places — the out-of-sight corner

of the playground, the entrance hallway at dismissal time.

Then, Dr. Sege said, “activating the bystanders” means changing the culture of

the school; through class discussions, parent meetings and consistent responses

to every incident, the school must put out the message that bullying will not be

tolerated.

So what should I ask at a checkup? How’s school, who are your friends, what do

you usually do at recess? It’s important to open the door, especially with

children in the most likely age groups, so that victims and bystanders won’t be

afraid to speak up. Parents of these children need to be encouraged to demand

that schools take action, and pediatricians probably need to be ready to talk to

the principal. And we need to follow up with the children to make sure the

situation gets better, and to check in on their emotional health and get them

help if they need it.

How about helping the bullies, who are, after all, also pediatric patients? Some

experts worry that schools simply suspend or expel the offenders without paying

attention to helping them and their families learn to function in a different

way.

“Zero-tolerance policies that school districts have are basically pushing the

debt forward,” Dr. Sege said. “We need to be more sophisticated.”

The way we understand bullying has changed, and it’s probably going to change

even more. (I haven’t even talked about cyberbullying, for example.) But anyone

working with children needs to start from the idea that bullying has long-term

consequences and that it is preventable.

I would still feel that same anger on my science-fair-winning patient’s behalf,

but I would now see his problem as a pediatric issue — and I hope I would be

able to offer a little more help, and a little more follow-up, appropriately

based in scientific research.

At Last, Facing Down

Bullies (and Their Enablers), 9.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/09/health/09klas.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Five Ways to Fix America’s

Schools

June 8, 2009

The New York Times

By HAROLD O. LEVY

AMERICAN education was once the best in the world. But today, our private and

public universities are losing their competitive edge to foreign institutions,

they are losing the advertising wars to for-profit colleges and they are losing

control over their own admissions because of an ill-conceived ranking system.

With the recession causing big state budget cuts, the situation in higher

education has turned critical. Here are a few radical ideas to improve matters:

•

Raise the age of compulsory education. Twenty-six states require children to

attend school until age 16, the rest until 17 or 18, but we should ensure that

all children stay in school until age 19. Simply completing high school no

longer provides students with an education sufficient for them to compete in the

21st-century economy. So every child should receive a year of post-secondary

education.

The benefits of an extra year of schooling are beyond question: high school

graduates can earn more than dropouts, have better health, more stable lives and

a longer life expectancy. College graduates do even better. Just as we are

moving toward a longer school day (where is it written that learning should end

at 3 p.m.?) and a longer school year (does anyone really believe pupils need a

three-month summer vacation?), so we should move to a longer school career.

President Obama recently embraced the possibility of extending public education

for a year after high school: “I ask every American to commit to at least one

year or more of higher education or career training.” He suggested that this

compulsory post-secondary education could be in a “community college or a

four-year school; vocational training or an apprenticeship.” (I helped start an

accredited online school of education, and firmly believe that the coursework

could also be delivered to students online.)

If the federal government ultimately pays for the extra year, it would be a

turning point at least as important as the passage of the 1862 Morrill Act that

gave rise to the state universities or the 1944 G.I. Bill that made college

affordable to our returning service personnel after World War II. Every college

trustee should be insisting that we make the president’s dream a reality.

And for those who graduate from high school early: they would receive, each year

until they turn 19, a scholarship equal to their state’s per pupil spending. In

New York, that could be nearly $15,000 per year. This proposal — which already

has been tried in a few states — has the neat side effect of encouraging quick

learners to graduate early and free up seats in our overcrowded high schools.

•

Use high-pressure sales tactics to curb truancy. Casual truancy is epidemic; in

many cities, including New York, roughly 30 percent of public school students

are absent a total of a month each year. Not surprisingly, truants become

dropouts.

But truant officers can borrow a page from salesmen, who have developed

high-pressure tactics so effective they can overwhelm the consumer’s will.

Making repeated home visits and early morning phone calls, securing written

commitments and eliciting oral commitments in front of witnesses might be

egregious tactics when used by, say, a credit card company. But these could be

valuable ways to compel parents to ensure that their children go to school every

day.

•

Advertise creatively and aggressively to encourage college enrollment. The

University of Phoenix, a private, for-profit institution, spent $278 million on

advertising, most of it online, in 2007. It was one of the principal sponsors of

Super Bowl XLII, which was held at University of Phoenix Stadium (not bad for an

institution that doesn’t even have a football team). The University of Phoenix’s

enrollment has clearly benefited from its advertising budget: with more than

350,000 students, its enrollment is surpassed by only a few state universities.

The University of Phoenix and other for profits have also established a crucial

niche recruiting and serving older students. Traditional colleges need to do far

better, using advertising to attract paying older students and to recruit the

more than 70 percent of the population who lack a post-secondary degree. They

have a built-in advantage, since attending a for-profit college instead of a

more prestigious, less expensive public college makes no more sense than buying

bottled water when the tap water tastes just as good.

•

Unseal college accreditation reports so that the Department of Education can

take over the business of ranking colleges and universities. Accreditation

reports — rigorous evaluations, prepared by representatives of peer institutions

— include everything students need to know when making decisions about schools,

yet the specifics of most reports remain secret.

Instead, students and their parents rely on U.S. News & World Report rankings

that are skewed by colleges, which contort their marketing efforts to maximize

the number of applicants whom they already know they will never accept, just to

improve their selectivity rankings. Meanwhile, private counselors charge

thousands of dollars claiming to know the “secret” of admissions. Aspiring

entrants submit far too many applications in the hope of beating the odds.

Everyone loses. Opening the accreditation reports to the public would provide a

better way.

•

The biggest improvement we can make in higher education is to produce more

qualified applicants. Half of the freshmen at community colleges and a third of

freshmen at four-year colleges matriculate with academic skills in at least one

subject too weak to allow them to do college work. Unsurprisingly, the average

college graduation rates even at four-year institutions are less than 60

percent.

The story at the graduate level is entirely predictable: in 2007, more than a

third of all research doctorates were awarded to foreigners, and the proportion

is far higher in the hard sciences. The problem goes well beyond the fact that

both our public schools and undergraduate institutions need to do a better job

preparing their students: too many parents are failing to insure that their

children are educated.

President Obama has again led the way: “As fathers and parents, we’ve got to

spend more time with them, and help them with their homework, and replace the

video game or the remote control with a book once in a while.” Better teachers,

smaller classes and more modern schools are all part of the solution. But

improving parenting skills and providing struggling parents with assistance are

part of the solution too.

At a time when it seems we have ever fewer globally competitive industries,

American higher education is a brand worth preserving.

Harold O. Levy, the New York City schools chancellor from 2000 to 2002, has

been a trustee of several colleges.

Five Ways to Fix

America’s Schools, NYT, 8.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/08/opinion/08levy.html

Letters

The M.B.A.’s Oath: I Promise to Be Good. Honest.

June 5, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “A Promise to Be

Ethical in an Era of Temptation” (Business Day, May 30):

As the holder of an M.B.A., I was thrilled to read that students and schools are

taking a greater interest in ethical business management.

I quote cases from my ethics course on a monthly if not weekly basis, and found

it one of the most interesting and beneficial parts of the program. It’s

wonderful to know that the next generation is not only becoming politically

active but socially active as well.

Cindy Yancosek

Saco, Me., May 31, 2009

•

To the Editor:

I compliment those Harvard Business School grads taking an oath to be honest and

truthful because, regrettably, a minority of our former alumni have recently

squandered their privileged and honest education to inflict incalculable damage

on the country and the world, especially in Washington and on Wall Street.

Fortunately, I believe that the vast majority of us have done honorable and

productive things with our advantages, and it’s encouraging to see at least some

new grads pledging to uphold that tradition. John G. Eresian

Hollis, N.H., May 31, 2009

The writer is a Harvard M.B.A., class of 1956.

To the Editor:

It is a testament to how far M.B.A. students have strayed from reality that they

feel the need to sign a public vow that boils down to, “I promise not to act

like a total jerk.”

Funny, I thought that should be the default! What other type of graduate program

must give its students a specific directive not to lie, cheat, steal or

otherwise act unethically? Erin Kim

Boston, May 31, 2009

The writer will be an M.B.A. student this fall.

The M.B.A.’s Oath: I

Promise to Be Good. Honest, NYT, 4.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/opinion/l05mba.html?hpw

Next Test: Value of $125,000-a-Year Teachers

June 5, 2009

The New York Times

By ELISSA GOOTMAN

So what kind of teachers could a school get if it paid them $125,000 a year?

An accomplished violist who infuses her music lessons with the neuroscience of

why one needs to practice, and creatively worded instructions like, “Pass the

melody gently, as if it were a bowl of Jell-O!”

A self-described “explorer” from Arizona who spent three decades honing her

craft at public, private, urban and rural schools.

Two with Ivy League degrees. And Joe Carbone, a phys ed teacher, who has the

most unusual résumé of the bunch, having worked as Kobe Bryant’s personal

trainer.

“Developed Kobe from 185 lbs. to 225 lbs. of pure muscle over eight years,” it

reads.

They are members of an eight-teacher dream team, lured to an innovative charter

school that will open in Washington Heights in September with salaries that

would make most teachers drop their chalk and swoon; $125,000 is nearly twice as

much as the average New York City public school teacher earns, and about two and

a half times as much as the national average for teacher salaries. They also

will be eligible for bonuses, based on schoolwide performance, of up to $25,000

in the second year.

The school, called the Equity Project, is premised on the theory that excellent

teachers — and not revolutionary technology, talented principals or small class

size — are the critical ingredient for success. Experts hope it could offer a

window into some of the most pressing and elusive questions in education: Is a

collection of superb teachers enough to make a great school? Are six-figure

salaries the way to get them? And just what makes a teacher great?

The school’s founder, Zeke M. Vanderhoek, 32, a Yale graduate who founded a test

prep company, has been grappling with just these issues. Over the past 15 months

he conducted a nationwide search that was almost the American Idol of education

— minus the popular vote, but complete with hometown visits (Mr. Vanderhoek

crisscrossed the country to observe the top 35 applicants in their natural

habitats) and misty-eyed fans (like the principal who got so emotional

recommending Casey Ash that, Mr. Vanderhoek recalled, she was “basically crying

on the phone with me, saying what a treasure he was.”)

Mr. Ash, 33, who teaches at an elementary school on the outskirts of Raleigh,

N.C., will take the social studies slot.

The Equity Project will open with 120 fifth graders chosen this spring in a

lottery that gave preference to children from the neighborhood and to low

academic performers; most students are from low-income Hispanic families. It

will grow to 480 children in Grades 5 to 8, with 28 teachers.

The school received 600 applications. Mr. Vanderhoek interviewed 100 in person.

Along the way, Mr. Vanderhoek, who taught at a middle school in Washington

Heights before founding Manhattan GMAT, learned a few lessons.

One was that a golden résumé and a well-run classroom are two different things.

“There are people who it’s like, wow, they look great on paper, but the kids

don’t respect them,” Mr. Vanderhoek said.

The eight winning candidates, he said, have some common traits, like a high

“engagement factor,” as measured by the portion of a given time frame during

which students seem so focused that they almost forget they are in class. They

were expert at redirecting potential troublemakers, a crucial skill for middle

school teachers. And they possessed a contagious enthusiasm — which Rhena Jasey,

30, Harvard Class of 2001, who has been teaching at a school in Maplewood, N.J.,

conveyed by introducing a math lesson with, “Oh, this is the fun part because I

looooooove math!” Says Mr. Vanderhoek: “You couldn’t help but get excited.”

Hired.

Teachers said the rigorous selection process was more gratifying than grueling.

“It’s so refreshing that somebody comes to a teacher and says, ‘Show me what you

know,’ ” said Oscar Quintero, who goes by Pepe and will teach special education.

“This is the first time in 30 years of teaching that anybody has been really

interested in what I do.”

The school will use only public money for everything but its building. It is

close to signing a lease for private space on 181st Street, to be covered by a

combination of public school financing, a charter school grant and what Mr.

Vanderhoek described as a “small amount” of private donations (he ultimately

hopes to raise enough private money to build a permanent space).

To make ends meet, teachers will hold responsibilities usually shouldered by

other staff members, like assistant principals (there will be none). There will

be no deans, substitute teachers (except for extended leaves) or teacher

coaches. Teachers will work longer hours and more days, and have 30 pupils,

about 6 more than the typical New York City fifth-grade class.

The principal, Mr. Vanderhoek, will earn just $90,000. Teachers will not have

the same retirement benefits as members of the city’s teachers’ union. And they

can be fired at will.

That did not scare Mr. Quintero, who is in his 60s and is moving from Florida;

Heather Wardwell, 37, who is leaving East Greenwich High School, in Rhode

Island, after a decade, to teach Latin; or Judith LeFevre, 54, the Arizona

teacher who earned about $40,000 as recently as two years ago.

Ms. LeFevre, who will teach science, wrote via e-mail that the school was “an

experiment of sorts, in which I’m one of the subjects.” She added, “This could

be unsettling were it not for the excitement of working with a team of master

teachers, all of whom are motivated to help every student succeed, with no

excuses and no blame.”

Her other teammates: Damion Frye, 32, who teaches English at Montclair High

School in New Jersey, has a master’s degree from Brown University and is

pursuing his doctorate at Columbia’s Teachers College, and Gina M. Galassi, 40,

who teaches music at Kingston High School in Ulster County, N.Y.

Mr. Carbone, 44, spent four years as head strength and conditioning coach for

the Los Angeles Lakers. He left for a quieter life in Spring Valley, N.Y., last

year, after overhearing one of his three sons say, “I want to play basketball,

but my dad hasn’t taught me yet.”

Whatever the magic formula for a great school or teacher may be, Mr. Vanderhoek

has come to believe that there is an essential ingredient to the search for such

teachers: Time spent in that teacher’s classroom, watching students learn. Then

again, his team has yet to hit the court.

“I have tremendous confidence that the staff is going to be excellent,” he said.

“But we will see.”

Next Test: Value of

$125,000-a-Year Teachers, NYT, 5.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/education/05charter.html?hp

A

Promise to Be Ethical in an Era of Immorality

May 30, 2009

The New York Times

By LESLIE WAYNE

When a new crop of future business leaders graduates from the Harvard

Business School next week, many of them will be taking a new oath that says, in

effect, greed is not good.

Nearly 20 percent of the graduating class have signed “The M.B.A. Oath,” a

voluntary student-led pledge that the goal of a business manager is to “serve

the greater good.” It promises that Harvard M.B.A.’s will act responsibly,

ethically and refrain from advancing their “own narrow ambitions” at the expense

of others.

What happened to making money?

That, of course, is still at the heart of the Harvard curriculum. But at Harvard

and other top business schools, there has been an explosion of interest in

ethics courses and in student activities — clubs, lectures, conferences — about

personal and corporate responsibility and on how to view business as more than a

money-making enterprise, but part of a large social community.

“We want to stand up and recite something out loud with our class,” said Teal

Carlock, who is graduating from Harvard and has accepted a job at Genentech.

“Fingers are now pointed at M.B.A.’s and we, as a class, have a real opportunity

to come together and set a standard as business leaders.”

At Columbia Business School, all students must pledge to an honor code: “As a

lifelong member of the Columbia Business School community, I adhere to the

principles of truth, integrity, and respect. I will not lie, cheat, steal, or

tolerate those who do.” The code has been in place for about three years and

came about after discussions between students and faculty.

In the post-Enron and post-Madoff era, the issue of ethics and corporate social

responsibility has taken on greater urgency among students about to graduate.

While this might easily be dismissed as a passing fancy — or simply a defensive

reaction to the current business environment — business school professors say

that is not the case. Rather, they say, they are seeing a generational shift

away from viewing an M.B.A. as simply an on-ramp to the road to riches.

Those graduating today, they say, are far more concerned about how corporations

affect the community, the lives of its workers and the environment. And business

schools are responding with more courses, new centers specializing in business

ethics and, in the case of Harvard, student-lead efforts to bring about a

professional code of conduct for M.B.A.’s, not unlike oaths that are taken by

lawyers and doctors.

“I don’t see this as something that will fade away,” said Diana C. Robertson, a

professor of business ethics at the Wharton School of the University of

Pennsylvania. “It’s coming from the students. I don’t know that we’ve seen such

a surge in this activism since the 1960s. This activism is different, but, like

that time, it is student-driven.”

A decade ago, Wharton had one or two professors who taught a required ethics

class. Today there are seven teaching an array of ethics classes that Ms.

Robertson said were among the most popular at the school. Since 1997, it has had

the Zicklin Center for Business Ethics Research. In addition, over the last five

years, students have formed clubs around the issues of ethics that sponsor

conferences, work on microfinance projects in Philadelphia or engage in social

impact consulting.

“It’s been a dramatic change,” Ms. Robertson added. “This generation was raised

learning about the environment and raised with the idea of a social conscience.

That does not apply to every student. But this year’s financial crisis and the

downturn have brought about a greater emphasis on social ethics and

responsibility.”

At Harvard, about 160 from a graduating class of about 800 have signed “The

M.B.A. Oath,” which its student advocates contend is the first step in trying to

develop a professional code not unlike the Hippocratic Oath for physicians or

the pledge taken by lawyers to uphold the law and Constitution.

Part of this has emerged by the beating that Wall Street and financiers have

taken in the current economic crisis, which can set the stage for reform,

Harvard students say.

“There is the feeling that we want our lives to mean something more and to run

organizations for the greater good,” said Max Anderson, one of the pledge’s

organizers who is about to leave Harvard and take a job at Bridgewater

Associates, a money management firm.

“No one wants to have their future criticized as a place filled with unethical

behaviors,” he added. “We want to learn from those mistakes, do things

differently and accept our duty to lead responsibly. Realistically, we have

tremendous potential to affect society for better or worse. Let’s humbly step

up. We are looking out for our own interest, but also for the interest of our

employees and the broader public.”

Bruce Kogut, director of the Sanford C. Bernstein & Company Center for

Leadership and Ethics at Columbia, said that this emphasis did not mean that

students were necessarily going to shun jobs that paid well. Rather, they will

think about how they earn their income, not just how much.

At Columbia, an ethics course is required, but students have also formed a

popular “Leadership and Ethics Board,” that sponsors lectures with topics like

“The Marie Antoinettes of Corporate America.”

“The courses make people aware that the financial crisis is not a technical

blip,” Mr. Kogut said. “We’re seeing a generational change that understands that

poverty is not just about Africa and India. They see inequities and the role of

business to address them.”

Dalia Rahman, who is about to leave Harvard for a job with Goldman Sachs in

London, said she signed the pledge because “it takes what we learned in class

and makes it more concrete. When you have to make a public vow, it’s a way to

commit to uphold principles.”

A Promise to Be Ethical

in an Era of Immorality, NYT, 30.5.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/30/business/30oath.html?ref=opinion

Recession Imperils Loan Forgiveness Programs

May 27, 2009

The New York Times

By JONATHAN D. GLATER

When a Kentucky agency cut back its program to forgive student loans for

schoolteachers, Travis B. Gay knew he and his wife, Stephanie — both

special-education teachers — were in trouble.

“We’d gotten married in June and bought a house, pretty much planned our whole

life,” said Mr. Gay, 26. Together, they had about $100,000 in student loans that

they expected the program to help them repay over five years.

Then, he said, “we get a letter in the mail saying that our forgiveness this

year was next to nothing.”

Now they are weighing whether to sell their three-bedroom house in Lawrenceburg,

Ky., some 20 miles west of Lexington. Otherwise, Mr. Gay said, “it’s going to be

very difficult for us to do our student loan payments, house payments and just

eat.”

From Kentucky to Iowa to California, loan forgiveness programs are on the

chopping block. Typically founded by their states to help students pay for

college, the state agencies and nonprofit organizations that make student loans

and sponsor these programs are getting less money from the federal government

and are having difficulty raising money elsewhere as a result of the financial

crisis.

The organizations say the repayment programs have been hurt by a broader effort

by Congress to tackle the high cost of the federal student loan program by

reducing subsidies to lenders.

Curbing the programs will make it harder to lure college graduates into

high-value but often low-paying fields like teaching and nursing.

While few schools may be hiring now in this economic climate, there may be

shortages later, educators say.

“You’re going to diminish the quality of the candidates who are thinking, ‘Do I

take my skills in math and science into industry or do I take them into the

classroom?’ ” said Tracey L. Bailey, who had loans forgiven in Florida and now

is director of education policy for the Association of American Educators.

The Kentucky Higher Education Student Loan Corporation is at the extreme in

cutting payments to people in midstream who have already finished their

educations and are repaying loans, but organizations in many other states have

curtailed their new offers to prospective teachers, nurses and others.

The New Hampshire Higher Education Loan Corporation has suspended its program

for teachers, and the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Authority has

done so for nurses and people called to active duty in the military.

Iowa Student Loan has reduced the maximum amounts offered to people in two of

its three program categories, one for teachers and one for certain types of

nurses, in an effort to ensure the programs will last. ALL Student Loan, which

is based in Los Angeles, ended a program for nurses last year.

The changes leave students without a critical escape hatch from their federal

college and graduate school loans, and they throw up a roadblock for those who

dream of teaching but fear an oppressive combination of low wages and high debt.

“I remember sitting in the financial aid office and them saying, ‘Pay for every

penny of it, pay for your books through loans, because they’re going to be

forgiven,’ ” Mr. Gay said. And he dutifully did, using federal loans to cover

some of the costs of his undergraduate degree in communications and all the

costs of his master’s program in special education, which he finished in 2006.

If he had known the forgiveness program was vulnerable, Mr. Gay said, he would

have chosen a different career, perhaps public relations. “Which I am actually

contemplating doing right now,” he added.

Teachers in Kentucky are hoping to get financing restored for the program. But

it is not clear where the money could come from.

“We’d obviously love to see something like that happen,” said Ted Franzeim, vice

president for customer relations of the organization. He added that the group

had never told participants that financing for forgiveness was guaranteed — a

point that schoolteachers dispute.

About 7,500 teachers, nurses and public interest lawyers have benefited from the

state’s loan forgiveness program since 2003, at a cost of $77 million, Mr.

Franzeim said.

The federal government and some states continue to support their programs to

lure promising young graduates to less lucrative jobs. The federal Education

Department still offers up to $17,500 in loan forgiveness to math, science or

education teachers who have worked for at least five years at an elementary or

secondary school in a low-income area.

New Mexico, New Jersey and New York pay for their programs directly instead of

relying on nonprofit organizations, and they have not been cut by lawmakers. In

Oregon the Legislature is debating whether to suspend funding of a program for

nurses.

Another problem for some of the nonprofit groups that rely on selling their

loans in a secondary market is that financing has dried up.

The Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, for example, has stopped offering

to reduce interest rates for borrowers working in public service fields like

teaching and firefighting, said Will Shaffner, director of business development

and governmental relations. The only investor willing to buy its loans now is

the federal Education Department, which purchases loans with standard terms

only.

There is no clear accounting of how many people were swayed by loan forgiveness

to pursue teaching, or how many might be deterred by the absence of such

programs. But the anecdotal evidence suggests the programs matter.

Mark Henderson said he weighed a job as an auditor at Humana, where he worked as

temporary help in 2005, against the chance to teach math, a subject he loved.

Kentucky’s loan forgiveness program persuaded him to try teaching.

“I thought, at least if I have somebody repay it, I can last five years and get

rid of this debt,” said Mr. Henderson, 26, a math teacher in Louisville. He

enrolled at Spalding University and graduated in 2006 with a master’s in

teaching; he is not yet in repayment on his loans because he is taking classes

to improve his earning potential.

He has ended up teaching at the very high school he attended, Mr. Henderson

said, and teaches geometry in the same classroom where he learned it.

“As it turned out, I really liked it,” he said, “and I’ll stick around for a

long time.”

Recession Imperils Loan

Forgiveness Programs, NYT, 27.5.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/27/your-money/student-loans/27forgive.html?hpw

Op-Ed Columnist

The Harlem Miracle

May 8, 2009

The New Yorrk Times

By DAVID BROOKS

The fight against poverty produces great programs but disappointing results.

You go visit an inner-city school, job-training program or community youth

center and you meet incredible people doing wonderful things. Then you look at

the results from the serious evaluations and you find that these inspiring

places are only producing incremental gains.

That’s why I was startled when I received an e-mail message from Roland Fryer, a

meticulous Harvard economist. It included this sentence: “The attached study has

changed my life as a scientist.”

Fryer and his colleague Will Dobbie have just finished a rigorous assessment of

the charter schools operated by the Harlem Children’s Zone. They compared

students in these schools to students in New York City as a whole and to

comparable students who entered the lottery to get into the Harlem Children’s

Zone schools, but weren’t selected.

They found that the Harlem Children’s Zone schools produced “enormous” gains.

The typical student entered the charter middle school, Promise Academy, in sixth

grade and scored in the 39th percentile among New York City students in math. By

the eighth grade, the typical student in the school was in the 74th percentile.

The typical student entered the school scoring in the 39th percentile in English

Language Arts (verbal ability). By eighth grade, the typical student was in the

53rd percentile.

Forgive some academic jargon, but the most common education reform ideas —

reducing class size, raising teacher pay, enrolling kids in Head Start — produce

gains of about 0.1 or 0.2 or 0.3 standard deviations. If you study policy, those

are the sorts of improvements you live with every day. Promise Academy produced

gains of 1.3 and 1.4 standard deviations. That’s off the charts. In math,

Promise Academy eliminated the achievement gap between its black students and

the city average for white students.

Let me repeat that. It eliminated the black-white achievement gap. “The results

changed my life as a researcher because I am no longer interested in marginal

changes,” Fryer wrote in a subsequent e-mail. What Geoffrey Canada, Harlem

Children’s Zone’s founder and president, has done is “the equivalent of curing

cancer for these kids. It’s amazing. It should be celebrated. But it almost

doesn’t matter if we stop there. We don’t have a way to replicate his cure, and

we need one since so many of our kids are dying — literally and figuratively.”

These results are powerful evidence in a long-running debate. Some experts,

mostly surrounding the education establishment, argue that schools alone can’t

produce big changes. The problems are in society, and you have to work on

broader issues like economic inequality. Reformers, on the other hand, have

argued that school-based approaches can produce big results. The Harlem

Children’s Zone results suggest the reformers are right. The Promise Academy

does provide health and psychological services, but it helps kids who aren’t

even involved in the other programs the organization offers.

To my mind, the results also vindicate an emerging model for low-income

students. Over the past decade, dozens of charter and independent schools, like

Promise Academy, have become no excuses schools. The basic theory is that

middle-class kids enter adolescence with certain working models in their heads:

what I can achieve; how to control impulses; how to work hard. Many kids from

poorer, disorganized homes don’t have these internalized models. The schools

create a disciplined, orderly and demanding counterculture to inculcate

middle-class values.

To understand the culture in these schools, I’d recommend “Whatever It Takes,” a

gripping account of Harlem Children’s Zone by my Times colleague Paul Tough, and

“Sweating the Small Stuff,” a superb survey of these sorts of schools by David

Whitman.

Basically, the no excuses schools pay meticulous attention to behavior and

attitudes. They teach students how to look at the person who is talking, how to

shake hands. These schools are academically rigorous and college-focused.

Promise Academy students who are performing below grade level spent twice as

much time in school as other students in New York City. Students who are

performing at grade level spend 50 percent more time in school.

They also smash the normal bureaucratic strictures that bind leaders in regular

schools. Promise Academy went through a tumultuous period as Canada searched for

the right teachers. Nearly half of the teachers did not return for the 2005-2006

school year. A third didn’t return for the 2006-2007 year. Assessments are

rigorous. Standardized tests are woven into the fabric of school life.

The approach works. Ever since welfare reform, we have had success with

intrusive government programs that combine paternalistic leadership, sufficient

funding and a ferocious commitment to traditional, middle-class values. We may

have found a remedy for the achievement gap. Which city is going to take up the

challenge? Omaha? Chicago? Yours?

The Harlem Miracle, NYT,

8.5.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/08/opinion/08brooks.html?ref=opinion

Letters

The Goal: Improve America’s Schools

March 17, 2009

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Ending the ‘Race to the Bottom’

” (editorial, March 12):

Although I share President Obama’s desire to improve America’s schools, I think

he is moving forward on bad advice. He’d do better to ask teachers and parents

how to make their schools more effective.

I would tell him that if the federal government wants to reward school success,

it should split those rewards among all those who have contributed: parents; the

whole school faculty, including the principal; and the students themselves. The

government might also reward the community that gave its schools financial and

moral support.

I’d also tell him that if innovation is desirable, all schools should be allowed

to innovate, not just charter schools. Why not free public schools from the

straitjackets of state textbooks, externally written curriculums and

one-size-fits-all instruction?

Finally, I’d tell him to lose the words “achievement” and “rigor,” which have no

connection to the inquisitiveness, determination, creative thinking and

perseverance students need for genuine lifelong learning.

Joanne Yatvin

Portland, Ore., March 12, 2009

The writer is a former teacher, principal and superintendent.

•

To the Editor:

President Obama’s financing of initiatives for performance pay for teachers will

accelerate the race to the bottom. Studies show that performance pay in other

areas has damaging effects.

Doctors receiving performance pay stopped treating the riskiest and sickest

patients. Performance pay in sports has been accompanied by athletes’ use of

banned drugs. And performance pay in the finance industry has transformed us

into the Enron nation.

In education, research on performance pay shows no substantive gains in student

achievement, and all Mr. Obama’s policy will do is reinforce the ill-conceived

notion that low-level standardized tests are a valid measure of student

achievement. Instead, pay teachers a salary that signals teaching as a

profession.

Jacqueline Ancess

New York, March 12, 2009

The writer is co-director of the National Center for Restructuring Education,

Schools and Teaching.

•

To the Editor:

President Obama wants more charter schools. This is devastating for small school

districts, for whom charters are an unfunded mandate. The public schools in

Albany, with 9,000 students, have been hit hard by nine charter schools.

The Albany public schools have paid more than $100 million to charters, a

gigantic loss for a small district. The result is a lack of resources for the

majority of Albany’s kids who still attend the public schools. We don’t need

more charters in Albany; we need a moratorium.

Mark S. Mishler

Albany, March 12, 2009

The writer is co-president of the Albany City P.T.A.

•

To the Editor:

After reading your editorial “Ending the ‘Race to the Bottom,’ ” and hearing

President Obama’s proposals for fixing America’s public schools, I have a

suggestion, a question and a challenge for our decision makers.

My suggestion is that our leaders, both economic and political, consider sending

their children to public schools.

My question is why we accept a two-tiered educational system: rich kids over

there (private), poor kids over here (public). If memory serves, we have already

decided that separate but equal does not work.

My challenge for President Obama, and all those in the halls of power, is to

invest time and energy in those public schools down the street. If you cannot

send your children, send yourselves. Do not dictate from above, but lead from

within.

Paul Clifford

Portland, Me., March 13, 2009

The writer is an eighth-grade social studies teacher.

•

To the Editor:

Re “ ‘No Picnic for Me Either,’ ” by David Brooks (column, March 13):

Mr. Brooks is exactly right: great teachers build strong relationships with

students on whom they impose high standards.

Mr. Brooks is also correct in saying that we need to know who these teachers

are, and which schools develop high achievement in their students and which do

not. Yes, we need data. We need to know, not to guess or hope.

However, Mr. Brooks’s faith in the standardized tests by which we gather data

strikes me as naïve. I taught English for years and have been an educator since

1957 and have yet to discover a better method of assessing my students’ progress

in learning how to write than reading their compositions closely, with a red

pencil, usually at least twice. If I could have substituted a standardized test

for that process, I could have gone to bed a lot earlier each night.

Could it be that our faith in standardized testing is based on the fact that it

costs much less than assessing real work?

One reading of Mr. Brooks’s column tells me more about his excellence as a

writer than a thousand standardized tests.

Stephen Davenport

Oakland, Calif., March 13, 2009

The Goal: Improve

America’s Schools, NYT, 17.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/17/opinion/l17educ.html

Editorial

Ending the ‘Race to

the Bottom’

March 12, 2009

The New York Times

There was an impressive breadth of knowledge and a welcome dose of candor in

President Obama’s first big speech on education, in which he served up an

informed analysis of the educational system from top to bottom. What really

mattered was that Mr. Obama did not wring his hands or speak in abstract about

states that have failed to raise their educational standards. Instead, he made

it clear that he was not afraid to embarrass the laggards — by naming them — and

that he would use a $100 billion education stimulus fund to create the changes

the country so desperately needs.

Mr. Obama signaled that he would take the case for reform directly to the

voters, instead of limiting the discussion to mandarins, lobbyists and

specialists huddled in Washington. Unlike his predecessor, who promised to leave

no child behind but did not deliver, this president is clearly ready to use his

political clout on education.

Mr. Obama spoke in terms that everyone could understand when he noted that only

a third of 13- and 14-year-olds read as well as they should and that this

country’s curriculum for eighth graders is two full years behind other

top-performing nations. Part of the problem, he said, is that this nation’s

schools have recently been engaged in “a race to the bottom” — most states have

adopted abysmally low standards and weak tests so that students who are

performing poorly in objective terms can look like high achievers come test

time.

The nation has a patchwork of standards that vary widely from state to state and

a system under which he said “fourth-grade readers in Mississippi are scoring

nearly 70 points lower than students in Wyoming — and they’re getting the same

grade.” In addition, Mr. Obama said, several states have standards so low that

students could end up on par with the bottom 40 percent of students around the

globe.

This is a recipe for economic disaster. Mr. Obama and Arne Duncan, the education

secretary, have rightly made clear that states that draw money from the stimulus

fund will have to create sorely needed data collection systems that show how

students are performing over time. They will also need to raise standards and

replace weak, fill-in-the-bubble tests with sophisticated examinations that

better measure problem-solving and critical thinking.

Mr. Obama understands that standards and tests alone won’t solve this problem.

He also called for incentive pay for teachers who work in shortage areas like

math and science and merit pay for teachers who are shown to produce the largest

achievement gains over time. At the same time, the president called for removing

underperforming teachers from the classroom.

In an effort to broaden innovation, the president called for lifting state and

city caps on charter schools. This could be a good thing, but only if the new

charter schools are run by groups with a proven record of excellence. Once

charter schools have opened, it becomes politically difficult to close them,

even in cases where they are bad or worse than their traditional counterparts.

The stimulus package can jump-start the reforms that Mr. Obama laid out in his

speech. But Congress will need to broaden and sustain those reforms in the

upcoming reauthorization of the No Child Left Behind Act. Only Congress can

fully replace the race to the bottom with a race to the top.

Ending the ‘Race to the

Bottom’, NYT, 12.3.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/12/opinion/12thu1.html

Obama Outlines Plan for Education Overhaul

March 11, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID STOUT

WASHINGTON — President Obama called for sweeping changes in

American education on Tuesday, urging states to lift limits on charter schools

and improve the quality of early childhood education while also signaling that

he intends to make good on his campaign promise of linking teacher pay to

performance.

Having secured tens of billions of dollars in additional financing for education

in the economic stimulus package and made clear his intent to seek more in his

budget, Mr. Obama used a speech here to flesh out how he would use federal money

and programs to influence policy at the state and local level.

His proposals reflected his party’s belief that education at all levels was

underfinanced in the Bush years and that reform should encompass more than

demands that schools show improved test scores. But they also showed a

willingness to challenge teachers’ unions and public school systems, and to

continue to demand more accountability.

The president said it was time to erase limits on the number of charter schools,

which his administration calls “laboratories of innovation,” while closing those

that are not working. He said 26 states and the District of Columbia now had

caps. Teachers’ unions have opposed charter schools in some places, saying they

take away financing for public schools, while supporting them in others.

Putting limits on charter schools, even in places where they are performing

well, “isn’t good for our children, our economy or our country,” Mr. Obama said.

In his recent budget message, he said that he hoped to double financing for