|

History > 2006 > UK > Wars > Iraq (V)

The Guardian

p. 32 30.12.2006

Obituary

Saddam Hussein

Brutal and opportunist dictator of Iraq,

he

wreaked havoc on his country,

the Middle East and the world

Saturday December 30, 2006

Guardian Unlimited

David Hirst

The Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, who was

executed this morning at the age of 69, may not yield many general biographies -

he was personally too uninteresting for that - but he will be a case study for

political scientists for years to come. For he was the model of a certain type

of developing world despot, who was, for over three decades, as successful in

his main ambition, which was taking and keeping total power, as he was

destructive in exercising it.

Yet at the same time, he was commonplace and

derivative. Stalin was his exemplar. The likeness came from more than conscious

emulation: he already resembled him in origin, temperament and method. Like him,

he was unique less in kind than in degree, in the extraordinary extent to which,

if the more squalid forms of human villainy are the sine qua non of the

successful tyrant, he embodied them. Like Stalin, too, he had little of the

flair or colour of other 20th-century despots, little mental brilliance, less

charisma, no redeeming passion or messianic fervour; he was only exceptional in

the magnitude of his thuggery, the brutality, opportunism and cunning of the

otherwise dull, grey apparatchik.

His rise to power was no more accidental than Stalin's. If he had not mastered

Iraq as he did, someone very similar probably would have, and very probably also

from Tikrit. Saddam's peculiar fortune was that, on his political majority, this

small, drab town, on the Tigris upstream from Baghdad, was already poised to

wrest a very special role in Iraqi history.

Saddam was born in the nearby village of Owja, into the mud house of his uncle,

Khairallah Tulfah, and into what a Tikriti contemporary of his called a world

"full of evil". His father, Hussein al-Majid, a landless peasant, had died

before his birth, and his mother, Sabha, could not support the orphan, until she

took a third husband.

Hassan Ibrahim took to extremes local Bedouin notions of a hardy upbringing. For

punishment, he beat his stepson with an asphalt-covered stick. Thus, from

earliest infancy, was Saddam nurtured - like a Stalin born into very similar

circumstances - in the bleak conviction that the world is a congenitally hostile

place, life a ceaseless struggle for survival, and survival only achieved

through total self-reliance, chronic mistrust and the imperious necessity to

destroy others before they destroy you.

The sufferings visited on the child begat the sufferings the grown man, warped,

paranoid, omnipotent, visited on an entire people. Like Stalin, he hid his

emotions behind an impenetrable facade of impassivity; but he assuredly had

emotions of a virulent kind - an insatiable thirst for vengeance on the world he

hated.

To fend off attack by other boys, Saddam carried an iron bar. It became the

instrument of his wanton cruelty; he would bring it to a red heat, then stab a

passing animal in the stomach, splitting it in half. Killing was considered a

badge of courage among his male relatives. Saddam's first murder was of a

shepherd from a nearby tribe. This, and three more in his teens, were proof of

manhood.

The small-town thug possessed all the personal qualifications he might need to

earn his place in the 20th-century's pantheon of tyrants. And the small town of

Tikrit, lying in the heart of the Sunni Muslim "triangle" of central Iraq

furnished the operational ones, too. Orthodox Sunni Arabs are only a small

minority, 15% at most, of Iraq's population, outnumbered by the Shias of the

south, 60% at least, and the Kurds of the mountainous north. Yet they always

dominated Iraq's political life.

Thanks partly to the decline of traditional river traffic, Tikritis had taken to

supplying the British-controlled Iraqi state with a disproportionate number of

its soldiers. With time and plentiful purges, they emerged within the army as a

distinct group; a preponderance which had been fortuitous at first finally

became so great they could deliberately enlarge it. A close-knit minority within

the Sunni minority, they exploited ties of region, clan and family to seize

control of the army, then the state. Saddam, perfect recruit to the sinister,

violent, conspiratorial underworld that was Iraqi politics, positioned himself

at the heart of this process.

He himself was never a soldier, but he used a formidable array of Tikritis who

were, and Ba'athists to boot. Ba'athism was a radical, pan-Arab nationalist

doctrine then sweeping the region. Though doubtless impelled in that direction

by the extreme, chauvinist beliefs of his uncle Khairallah, who had been

dismissed from the army and imprisoned for five years for his part in a 1941

attack on an RAF base near Baghdad, it was mainly out of convenience, not

conviction, that Saddam joined the party; strong in Tikrit and the Sunni

"triangle", dedicated to force not persuasion, it readily appealed to a man of

his ambition and temper.

In theory he remained a Ba'athist to his dying day, but for him Ba'athism was

always an apparatus, never an ideology: no sooner was command of the one

complete than he dispensed entirely with the other. For next to brutality,

opportunism was his chief trait. Not Stalin himself could have governed with

such whimsy, or lurched, ideologically, politically, strategically, from one

extreme to another with quite such ease, regularity, and disastrous

consequences, and yet still, incredibly, retain command to the end.

The Ba'ath, and other "revolutionary" parties, had come into their own with the

overthrow, in 1958, of the "reactionary", British-created Hashemite monarchy.

They quickly fell out with General Kassem's new regime and with each other,

rivalries that expressed themselves mainly in streetfighting and assassinations.

That was the way of life that Saddam fell into as a street-gang leader, after

going, in 1955, to live with his uncle in Baghdad to study at Karkh high school.

Saddam first achieved national prominence in 1959 with a bungled attempt to kill

Kassem. He seems to have lost his nerve and opened fire prematurely. But though

his role was less than glorious, it became an essential component of the Saddam

legend - that of the dauntless young revolutionary extracting a bullet from his

leg with his own hand, and, with security forces in hot pursuit, swimming the

icy waters of the Euphrates, knife between clenched teeth, before galloping to

safety across the Syrian desert; eventually fetching up in Cairo, where his

university law studies were terminated by the next political convulsion back

home - Kassem's overthrow in February 1963.

Securing a share in the new regime, the Ba'athists lost it the following

November when they fell out with the other parties. Pushed back into the

underground, Saddam took what subsequently turned out to be his first, concrete

step towards supreme office. In 1964, he formed the Jihaz al-Hunein, the

Instrument of Yearning, the first, embryonic version of a terror apparatus of

which, in its full fruition, Stalin would not have been ashamed.

It was an outgrowth of the party. That meant that, through it, Saddam, though

not an officer, could now see his way to the summit. But at this stage his main

asset was his collaboration with his fellow-Tikriti, Brigadier Ahmad Hassan

al-Bakr. Thanks to a combination of Bakr's traditional military means and

Saddam's new, "civilian" ones, the pair pulled off the "glorious July 1968

Revolution".

At 31, as deputy secretary general of the Ba'ath party, Saddam was the power

behind President Bakr's throne. But at first he assumed, like Stalin in his

similar period, a disarmingly modest and retiring demeanour as he lay the

foundations of what he called a new kind of rule; "With our party methods," he

said, "there is no chance for anyone who disagrees with us to jump on a couple

of tanks and overthrow the government." Gradually he subordinated the army to

the party.

There was nothing modest about the Ba'athists' inaugural reign of terror; few

knew it then, but it was chiefly his handiwork, and quite different from

anything hitherto experienced in a country already notorious for its harsh

political tradition. Saddam's henchmen presided over "revolutionary tribunals"

that sent hundreds to the firing squad on charges of puerile, trumped up

absurdity. They called on "the masses" to "come and enjoy the feast": the

hanging of "Jewish spies" in Liberation Square amid ghoulish festivities and

bloodcurdling official harangues.

That was the public face. Behind it were such places as the Palace of the End.

So called because King Faisal died there in the 1958 Revolution, it was now more

aptly named than ever. Saddam's first security chief, Nadhim Kzar, had turned it

into a chamber of horrors. But Kzar, a Shia, nursed a grudge against his Sunni

patrons; in 1973, he turned against them; Saddam, Bakr and a host of top

Tikritis had a very narrow escape indeed.

Thereafter the badly shaken number two relied almost entirely on Tikritis; the

more sensitive the post, the more closely related its incumbent would be to

himself. Meanwhile, with guile and infinite patience, he worked his way towards

his supreme goal. Purge followed judicious purge, first aimed at the Ba'athists'

rivals, then the army, then the party, then influential, respected, or

strategically located people whom he deemed most liable, at some point, to cry

halt to his inexorable ascension.

When, in June 1979, all was set for him to depose and succeed the ailing Bakr,

he could have accomplished it with bloodless ease. But he wilfully, gratuitously

chose blood in what was a psychological as well as a symbolic necessity. He had

to inaugurate the "era of Saddam Hussein" with a rite whose message would be

unmistakable: there had arisen in Mesopotamia a ruler who, in his barbaric

splendour, cruelty and caprice, was to yield nothing to its despots of old.

Only now did he emerge, personally and very publicly, as accuser, judge and

executioner in one. He called an extraordinary meeting of senior party cadres.

They were solemnly informed that "a gang disloyal to the party and the

revolution" had mounted a "base conspiracy" in the service of "Zionism and the

forces of darkness", and that all the "traitors" were right there, with them, in

the hall. One of their ringleaders, brought straight from prison, made a long

and detailed confession of his "horrible crime".

Saddam, puffing on a Havana cigar, calmly watched the proceedings as if they had

nothing to do with him. Then he took the podium. He began to read out the

"traitors'" names, slowly and theatrically; he seemed quite overcome as he did

so, pausing only to light his cigar or wipe away his tears with a handkerchief.

All 66 "traitors" were led away one by one.

Thus did the new president make inaugural use of that essential weapon of the

ultimate tyrant, the occasional flamboyant, contemptuous act of utter

lawlessness, turpitude or unpredictability, and the enforced prostration of his

whole apparatus, in praise and rejoicing, before it. Those of the audience who

had not been named showed their relief with hysterical chants of gratitude and a

baying for the blood of their fallen comrades.

Saddam then called on ministers and party leaders to join him in personally

carrying out the "democratic executions"; every party branch in the country sent

an armed delegate to assist them. It was, he said, "the first time in the

history of revolutionary movements without exception, or perhaps of human

struggle, that over half the supreme leadership had taken part in a tribunal"

which condemned the other half. "We are now," he confided, "in our Stalinist

era."

But in one way he had actually surpassed his exemplar. Upon entering the

Kremlin, the former Georgian streetfighter had at least kept himself fittingly

aloof from his "great terror". Not Saddam. Newly exalted, he was to remain

down-to-earth too; new caliph of Baghdad, but, direct participant in his own

terror, very much the Tikriti gangster, too.

The "Leader, President, Struggler" now emerged as a regional and international

actor with the disproportionate capacity for promoting well-being and order or

wreaking havoc which Iraq's great strategic and political importance, vast oil

wealth, relatively educated citizenry and powerful army conferred on him. With

U-turns, blunders and megalomaniac whimsies, he chose havoc; he wreaked it on

the region and the world, but above all on Iraq itself.

In September 1980 he went to war against Iran. It was known as "Saddam's

Qadisiyah", after the Arabs' early Islamic victory over the Persians. His

official, strictly limited war aims revolved round the Shatt al-Arab estuary and

his determination to renegotiate the "Algiers agreement" he had concluded a mere

five years before. A dire emergency had forced that humiliation on him: the

Iraqi army had been close to defeat in its campaign to suppress the last great,

Iranian-backed Kurdish uprising led by Mullah Mustafa Barazani. The quid pro quo

for Algiers had been the American-inspired withdrawal of the Shah's support for

Barazani.

His "Qadisiyah", first of his spectacular volte-faces, was now to avenge the

humiliation. But he also had a higher, unofficial aim: to weaken or destroy the

Ayatollah Khomeini's new-born Islamic Republic, or at least its subversive

potentialities in Iraq itself. For Iraq's Shia majority now saw in their Iranian

co-religionists a means of bringing down Sunni minority rule. Hitherto closely

bound to the Soviet Union, Saddam now bid for the west's favour as the Shah's

natural heir as the "strong man" of the Gulf.

In the terrible eight-year struggle that followed, the Ayatollah's Iran

remorselessly turned the tables on the Iraqi aggressor, recovered all its

conquered territory, and, in a series of fearsome "human wave" offensives, tried

to conquer Iraq, and turn it into the world's second "Islamic Republic".

That would have been a geopolitical upheaval of incalculable consequences. To

forestall it, the west, beneath a mask of outward neutrality, put its weight

behind one unlovely regime because it found the other unlovelier still. While

the frightened, oil-rich Gulf furnished cash, the west furnished conventional

weapons, and the means to manufacture a whole array of unconventional ones:

nuclear, chemical and biological. Almost miraculously, Saddam held out, until,

in July 1988, Khomeini drank from what he called "the poisoned chalice" of a

ceasefire.

Of course, Saddam hailed this, his "first Gulf war", as a victory. Though what

possible victory there could have been in an outcome which, in addition to

hundreds of thousands of dead, wounded and captured, immense physical

destruction and economic havoc, left Iraq on a permanent war footing, still

seeking to renegotiate the status of the Shatt al-Arab?

Even if he could not officially admit it, he had good reason to give his people

some recompense for their sufferings. He made as if to offer them two things,

material betterment and some democratisation. But he cannot have been serious

about either. Thanks to the ravages of his "Qadisiyah", he had no money for

economic reconstruction. And, in another great volte-face, he staged a virtual

counter-revolution against the one ideal of Ba'athism, its socialism, which he

had made a passable attempt to put into practice. Worse, the main beneficiaries

of the economic revisionism were the Tikriti pillars of his regime, now corrupt

as well as despotic.

With the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu, the east European dictator he most closely

resembled, Saddam abandoned talk of "the new pluralist trends" he discerned in

the world. Indeed, he persisted, more surrealistically than ever, in the

despot's law: the more disastrous his deeds the more they should be glorified.

His cult of personality expressed itself most overbearingly in monumental

architecture, where the public - an amazing array of bizarre or futuristic

memorials to his "Qadisiyah" - merged with the private (his proliferating

palaces) in grandiose tribute to all the attributes, bordering on the divine,

ascribed to him.

It reflected a degree of control that enabled him, amazingly, to embark, within

two years of the first, on his "second Gulf war", and then, more amazingly

still, to survive that yet greater calamity in its turn. It was a resort to the

classic diversionary expedient, a flashy foreign adventure, of the dictator in

trouble at home. He cast himself once again as the pan-Arab champion, boasting

that, having secured the Arabs' eastern flank against the Persians, he was now

turning his attention westwards, with the aim of settling scores with the Arabs'

other great foe, the Zionists. He threatened "to burn half of Israel" with his

weapons of mass destruction, thrilling large segments of an Arab public

desperately short of credible heroes.

But instead of Israel, it was Kuwait which, on the night of August 2 1990,

Saddam attacked, or, rather, gobbled up in its entirety. Hardly had he done that

than, to appease Iran, he unilaterally re-accepted the Algiers agreement on the

Shatt al-Arab. It was the most breathtaking of his volte-faces; even as he

dragged his people into another unprovoked war, he was in effect telling them

that, in the first, they had shed all that blood, sweat and tears for nothing.

The Kuwait invasion was the ultimate excess, whimsy and Promethean delusion of

the despot: the belief that he could get away with anything. Yet nothing had

encouraged this excess like the west's indulgence of his earlier ones. Sure, it

had never loved him. But neither had it protested at his use of chemical weapons

against Iran. It had contented itself with little more than a wringing of hands

when he went on to gas his own people.

In March 1988, in revenge for an Iranian territorial gain, he wiped out 5,000

Kurdish inhabitants of Halabja; then, the war over, he wiped out several

thousand more in "Operation Anfal", his final, genocidal attempt to solve his

Kurdish problem. In effect, the west's reaction had been to treat the Kurds as

an internal Iraqi affair; exterminating them en masse may have briefly stirred

the international conscience, but it tended, if anything, to reinforce the

existing international order.

But now that he was so ungratefully, so shockingly threatening this order

itself, the west finally awoke to the true nature of the monster it had

nurtured. Before long, Saddam faced an American-led army of half a million men

assembled in the Arabian desert.

He did not blench. And for a few months he won adulation as the latter-day

Saladin, who, after Kuwait, would go on to liberate Palestine. He said his army

was eagerly awaiting the coalition's great land offensive to reconquer Kuwait;

in "the mother of all battles", Iraq would "water the desert with American

blood".

But he stood no chance. For a month, allied aircraft rained high-tech

devastation on his army, air force, economic and strategic infrastructure. He

panicked, ordering his army's withdrawal from Kuwait. It was not enough for the

allies. As their ground forces swept almost unopposed through Kuwait, then into

southern Iraq, the withdrawal became a rout. They could have marched on Baghdad.

He caved in utterly, accepting every demand that the allies made. Only then did

they cease their advance.

They had shattered most of his "million-man army" except for its elite

Republican Guards, held in reserve to defend the regime against the wrath of the

people. And this time their wrath was truly unleashed. The two oppressed

majorities, Shias and Kurds, staged their great uprisings. These began

spontaneously, when a Shia tank commander, having fled from Kuwait to Basra,

positioned his vehicle in front of one of those gigantic, ubiquitous murals of

the tyrant and addressed it thus: "What has befallen us of defeat, shame and

humiliation, Saddam, is the result of your follies, your miscalculations and

your irresponsible actions."

But the uprisings foundered on the rock of Saddam's residual strength, western

betrayal and, in the south, their own disorganisation, vengeful excesses and

failure to distance themselves from Iranian expansionist designs. Exploiting the

Sunni minority's fear that if he went, so would many of them, in the most

horrible of massacres, Saddam sent in his guards. Dreadful atrocities

accompanied the slow reconquest of the south. And when the Guards turned north,

the whole population of "liberated" Kurdistan fled in panic through snow and

bitter cold to Iran and Turkey.

The television images of that grim stampede caught the measure of western

betrayal. Four weeks previously, President George Bush senior had urged the

Iraqis to rise up. But when they did so, he turned a deaf ear to their pleas for

help. "New Hitler" Saddam might be, but he was also the only barrier against the

possible break-up of Iraq itself. Saudi Arabia, for one, could not tolerate the

prospect. It told the US it would work to replace Saddam with an army officer

who would keep the country in safe, authoritarian, Sunni Muslim hands.

Saddam was saved again. And for 12 more years he hung on, as his people sank

into social, economic and political miseries incomparably greater than those

which had propelled him into Kuwait. Tikriti solidarity continued to preserve

him against putsch and assassination. And never again would the people stage an

uprising without assurance of success. Only the west could provide that. But the

West, preoccupied with other crises, was paralysed.

It would, or could, not withdraw from what, after the Gulf war, it had put in

place, a curious, contradictory amalgam of UN sanctions that penalised the Iraqi

people, not its rulers, a moral commitment to safeguard "liberated" Kurdistan,

an ineffectual "no-fly zone" over the Shia south.

But it also feared to go further in and, completing the logic of what it had

begun, join forces with a serious Iraqi opposition that could bring the tyrant

down and keep the country in one piece thereafter. This was inertia, which, the

longer it lasted, the more dearly it would pay for in the end. Every now and

then confrontations erupted between the world's only superpower and this most

exasperating of "rogue states"; they arose out of Saddam's attempts to break out

of his "box", via some renewed threat to Kuwait, an incursion into the

western-protected Kurdish enclave, or - most persistently - showdowns over the

UN's mission to divest Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction.

In the last of them, in 1998, his elite military and security apparatus took a

four-day pounding from the air. Heavy though this was, it proved to be the last,

symbolic flourish behind which the Clinton administration acquiesced in what,

with the expulsion of the arms inspectors, was a diplomatic victory for Saddam.

In the end, it was less his own misdeeds that brought the despot down, but those

of the man who, for a while, supplanted him as America's ultimate villain, Osama

bin Laden. Saddam had nothing to do with 9/11, but he fell victim none the less

to the crusading militarism, the new doctrine of the pre-emptive strike, the

close identification with a rightwing Israeli agenda, that now took full

possession of the administration of George Bush junior. Iraq became the first

target among the three states (with Iran and North Korea) that it had placed on

its "axis of evil", and with the launch of the invasion by the US, UK and their

allies in March 2003, Saddam's days were numbered.

However, three years passed between his capture and his execution yesterday. In

December 2003, following a tip-off from an intelligence source, US forces found

him hiding in an underground refuge on a farm near Tikrit, where his life had

begun. It was the middle of the next year before he was transferred to Iraqi

custody, and in July 2004 the former president appeared in court to hear

criminal charges. Another year passed before the prosecution was ready to

proceed with counts related to the massacre in the small Shia town of Dujail in

1982. The trial at last opened in October 2005 and the proceedings were

immediately adjourned. Saddam, who two months earlier had sacked his legal team,

pleaded innocence. A second trial on war crimes charges relating to the 1988

Anfal campaign opened on August 21 this year. He refused to enter a plea, and

episodes of black farce, which characterised his earlier appearances in court,

recurred, with the judge switching of his microphone because of his

interruptions, and ejecting him from the court four times. The trial was

adjourned on October 11, but on November 5 the court handed down a guilty

verdict and sentenced Saddam to death by hanging.

Saddam married Saida Khairallah in 1963. Their sons Uday and Qusay (obituaries,

July 23 2003) were killed by American forces; they had three daughters.

· Saddam Hussein abd al-Majid, politician, born April 28 1937; died December 30

2006.

Saddam Hussein, G, 30.12.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/Iraq/Story/0,,1980293,00.html

11.30am update

Saddam Hussein executed

Saturday December 30, 2006

Guardian Unlimited

Staff and agencies

Saddam Hussein was executed at dawn today

following his conviction by an Iraqi court for crimes against humanity.

The death sentence was carried out at a former

military intelligence headquarters in a Shia district of Baghdad at 6am local

time (3am GMT).

One of those who witnessed the hanging, Sami al-Askari, an adviser to the Iraqi

prime minister, said Saddam struggled when he was taken from his cell in a US

military prison but was composed in his last moments. He expressed no remorse.

The former dictator, dressed in black, refused a hood and said he wanted the

Koran he carried to the gallows to be given to a friend. "Before the rope was

put around his neck, Saddam shouted. 'God is great. The nation will be

victorious and Palestine is Arab'," Mr Askari told the Associated Press.

Another witness, Mowaffak al-Rubaie, Iraq's national security advisor, said

Saddam was "strangely submissive" in the execution chamber. "He was a broken

man," he said. "He was afraid. You could see fear in his face."

In a prepared statement, George Bush cautioned that Saddam's execution would not

stop the violence in Iraq but said it was "an important milestone on Iraq's

course to becoming a democracy that can govern, sustain and defend itself, and

be an ally in the war on terror."

The office of the Iraqi prime minister, Nuri al-Maliki, released a statement

that said Saddam's execution was a "strong lesson" to ruthless leaders who

commit crimes against their own people. The Iraqi state broadcaster, Iraqiya,

later aired film of the lead-up to the execution but not the hanging itself.

Saddam's execution was followed by reports of a car bombing with as many as 30

dead in the Shia city of Kufa.

In Sadr City, a major Shia area in Baghdad, people danced in the streets while

others fired guns in the air to celebrate. The government did not impose a

round-the-clock curfew as it did last month when Saddam was convicted.

The execution, which became imminent after his appeal was this week rejected,

brought to an end the life of one of the Middle East's most brutal dictators.

Launching the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, campaigns against the Kurds and putting

down the southern Shia revolt that followed the 1991 Gulf war - triggered by his

invasion of Kuwait - put the casualties attributable to his rule into the

hundreds of thousands.

But the conviction that led to his hanging was for a relatively lower figure -

the deaths of 148 men and boys from the Shia town of Dujail, where members of an

opposition group had made a botched attempt to assassinate him in 1982.

In Iraq opinion was divided sharply along sectarian lines, with Sunni Muslims

warning of "bloodbaths in the streets".

Even among Shia Muslims, terrorised for decades by Saddam, there was a sense of

hopelessness. "They can kill him 10 times but it won't bring safety to the

streets because there is no state of law," said one Shia taxi driver who gave

his name as Shawkat.

In the Kurdish north, jubilation was tempered by the fear of deeper sectarian

tensions and disappointment that Saddam would now not be able to stand trial for

other charges including the gas attack on the town of Halabja that killed 5,000

people in 1988.

"It would have been much better for the execution to have taken place in

Halabja, not in Baghdad," said Barham Khorsheed, a Kurd.

Many critics dismissed the conduct of the trial and Saddam Hussein's defence

team had accused the Iraqi government of interfering in the proceedings. The

latter complaint was backed by the US-based Human Rights Watch.

The process that ended with his execution began with the launch of the 2003

US-led war to disarm Iraq's claimed weapons of mass destruction.

Mr Bush committed the US to a policy of regime change and Saddam was ousted

within weeks of the invasion. Just over eight months later, US forces captured

him from his hiding place in a hole near his hometown of Tikrit.

Paul Bremer, the US civilian administrator in Iraq, told a press conference: "We

got him". For the first time, he showed video footage of a dishevelled former

dictator, with unkempt hair and beard, being inspected by military doctors.

His rise was through the Ba'ath party. The party, which had participated in

previous coups against Iraqi governments, took complete power in 1968.

Saddam was deputy president and regime strongman, responsible for internal

security. But used his position to build a powerbase allowing him to supplant

Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr as president in 1979. On taking power he launched a massive

purge of the party.

Iraq under Saddam was under the thuggish rule of the dictator and, frequently,

his relatives and cronies from Tikrit.

Saddam Hussein's half-brother, Barzan al-Tikriti, and Iraq's former chief judge,

Awad Hamed al-Bandar, were also sentenced to death at the close of the Dujail

trial.

Iraqiya television initially reported the two were also hanged today but

officials later said only Saddam was executed.

Saddam Hussein executed, G, 30.12.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/Iraq/Story/0,,1980290,00.html

Saddam executed

End of tyrannical era as former dictator is hanged for crimes against

humanity

Saturday December 30, 2006

Guardian

Brian Whitaker, Michael Howard, Ghaith Abdul Ahad and agencies in Baghdad

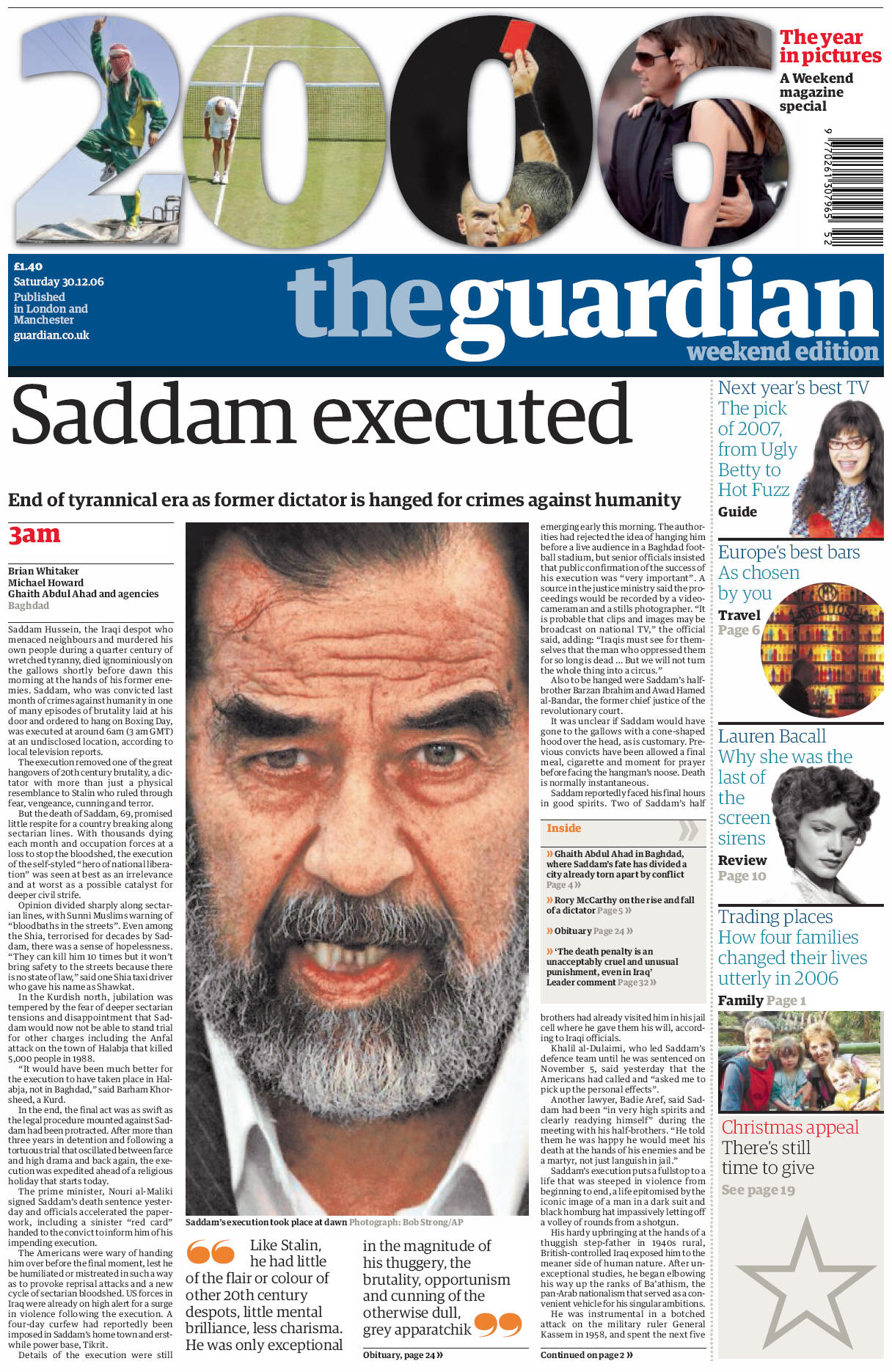

Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi despot who menaced neighbours and murdered his own

people during a quarter century of wretched tyranny, died ignominiously on the

gallows shortly before dawn this morning at the hands of his former enemies.

Saddam, who was convicted last month of crimes against humanity in one of

many episodes of brutality laid at his door and ordered to hang on Boxing Day,

was executed at around 6am (3 am GMT) at an undisclosed location, according to

local television reports.

The execution removed one of the great hangovers of 20th century brutality, a

dictator with more than just a physical resemblance to Stalin who ruled through

fear, vengeance, cunning and terror.

But the death of Saddam, 69, promised little respite for a country breaking

along sectarian lines. With thousands dying each month and occupation forces at

a loss to stop the bloodshed, the execution of the self-styled "hero of national

liberation" was seen at best as an irrelevance and at worst as a possible

catalyst for deeper civil strife.

Opinion divided sharply along sectarian lines, with Sunni Muslims warning of

"bloodbaths in the streets". Even among the Shia, terrorised for decades by

Saddam, there was a sense of hopelessness. "They can kill him 10 times but it

won't bring safety to the streets because there is no state of law," said one

Shia taxi driver who gave his name as Shawkat.

In the Kurdish north, jubilation was tempered by the fear of deeper sectarian

tensions and disappointment that Saddam would now not be able to stand trial for

other charges including the Anfal attack on the town of Halabja that killed

5,000 people in 1988.

"It would have been much better for the execution to have taken place in

Halabja, not in Baghdad," said Barham Khorsheed, a Kurd.

In the end, the final act was as swift as the legal procedure mounted against

Saddam had been protracted. After more than three years in detention and

following a tortuous trial that oscillated between farce and high drama and back

again, the execution was expedited ahead of a religious holiday that starts

today.

The prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki signed Saddam's death sentence yesterday and

officials accelerated the paperwork, including a sinister "red card" handed to

the convict to inform him of his impending execution.

The Americans were wary of handing him over before the final moment, lest he be

humiliated or mistreated in such a way as to provoke reprisal attacks and a new

cycle of sectarian bloodshed. US forces in Iraq were already on high alert for a

surge in violence following the execution. A four-day curfew had reportedly been

imposed in Saddam's home town and erstwhile power base, Tikrit.

Details of the execution were still emerging early this morning. The authorities

had rejected the idea of hanging him before a live audience in a Baghdad

football stadium, but senior officials insisted that public confirmation of the

success of his execution was "very important". A source in the justice ministry

said the proceedings would be recorded by a video-cameraman and a stills

photographer. "It is probable that clips and images may be broadcast on national

TV," the official said, adding: "Iraqis must see for themselves that the man who

oppressed them for so long is dead ... But we will not turn the whole thing into

a circus."

Also to be hanged were Saddam's half-brother Barzan Ibrahim and Awad Hamed

al-Bandar, the former chief justice of the revolutionary court.

It was unclear if Saddam would have gone to the gallows with a cone-shaped hood

over the head, as is customary. Previous convicts have been allowed a final

meal, cigarette and moment for prayer before facing the hangman's noose. Death

is normally instantaneous.

Saddam reportedly faced his final hours in good spirits. Two of Saddam's half

brothers had already visited him in his jail cell where he gave them his will,

according to Iraqi officials.

Khalil al-Dulaimi, who led Saddam's defence team until he was sentenced on

November 5, said yesterday that the Americans had called and "asked me to pick

up the personal effects".

Another lawyer, Badie Aref, said Saddam had been "in very high spirits and

clearly readying himself" during the meeting with his half-brothers. "He told

them he was happy he would meet his death at the hands of his enemies and be a

martyr, not just languish in jail."

Saddam's execution puts a fullstop to a life that was steeped in violence from

beginning to end, a life epitomised by the iconic image of a man in a dark suit

and black homburg hat impassively letting off a volley of rounds from a shotgun.

His hardy upbringing at the hands of a thuggish step-father in 1940s rural,

British-controlled Iraq exposed him to the meaner side of human nature. After

unexceptional studies, he began elbowing his way up the ranks of Ba'athism, the

pan-Arab nationalism that served as a convenient vehicle for his singular

ambitions.

He was instrumental in a botched attack on the military ruler General Kassem in

1958, and spent the next five years in Cairo, returning only when Kassem was

overthrown in 1963. Five years later, the Ba'athists pulled off a coup and

Saddam remained the power behind the throne until he deposed his fellow Tikriti,

Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr in 1979.

Saddam immediately led his country in an eight-year war with Iran, a campaign

that might have failed if it had not been for covert western support. Within two

years of the ceasefire, he marched his troops into Kuwait, triggering the first

gulf war that almost drove him from power.

His last decade in power was dominated by the cat-and-mouse game of avoiding UN

sanctions, which ruined the economy and the prosperity of ordinary Iraqis, while

Saddam, his family and their cronies grew wealthier and wealthier. And the

paranoia deepened. There were at least a dozen intelligence agencies, mostly

spying on each other and all spying on the Iraqi population. Saddam's image

towered over a cowed society, daubed on vast concrete hoardings across the

country in various poses: an army general, a tribal leader, an observant Muslim.

The beginning of the end came eight months after US forces rolled into Baghdad,

when he was pulled, hirsute and disoriented from a hidey-hole in the ground in

December 2003. There were times during the legal procedure when his enemies must

have doubted that the outcome they sought would come. Today it did.

Saddam executed, G,

30.12.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/Iraq/Story/0,,1980225,00.html?gusrc=rss&feed=12

12.45pm

British soldier killed in Iraq

Friday December 29, 2006

Press Association

Guardian Unlimited

A British soldier was killed today in Basra,

southern Iraq, when a roadside bomb hit the vehicle he was travelling in, the

Ministry of Defence said.

The soldier, from the 2nd Battalion Duke of

Lancaster's Regiment, was taking part in a routine patrol in a Warrior armoured

fighting vehicle when it was targeted, the MoD said.

He suffered serious injuries and was airlifted to the field hospital at Shaibah

logistics base but later died. There were no other casualties.

The death takes the number of UK service personnel who have died in Iraq since

the start of the war in 2003 to 127.

British soldier killed in Iraq, G, 29.12.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/Iraq/Story/0,,1979948,00.html

Iraq's shallow justice

Saddam's trial has been a missed opportunity

for the government to respect human rights

Friday December 29, 2006

Richard Dicker

The Guardian

The imminent execution of Saddam Hussein and

two other former Iraqi officials marks a further step away from respect for

human rights and the rule of law in a deeply polarised and violent Iraq. For 15

years Human Rights Watch and other organisations documented rights violations

committed by the former government. There is no question that Saddam and his

cohort were responsible for horrific practices. But by ratifying the execution

order the tribunal's appeals chamber has compounded the serious errors committed

at trial and further undermined the credibility of the process.

The trial judgment was not finished when the verdict and sentence were announced

on November 5. The record only became available to defence lawyers on November

22. According to the tribunal's statute, the defence attorneys had to file their

appeals on December 5, which gave them less than two weeks to respond to the

300-page trial decision. The appeals chamber never held a hearing to consider

the legal arguments presented as allowed by Iraqi law. It defies belief that the

appeals chamber could fairly review a 300-page decision together with written

submissions by the defence and consider all the relevant issues in less than

three weeks.

This follows a trial whose serious flaws rendered the verdict unsound. The trial

was undermined from the start by persistent political interference from the

Iraqi government. Furthermore, the rights of the defendants were systematically

denied by failures to disclose key evidence to the defence. There were also

serious violations of the defendants' rights to confront witnesses testifying

against them. Most disturbing were the frequent lapses of judicial demeanour by

the trial's second presiding judge. In January, the first chief judge resigned

in protest over the public criticism of his trial management practices by

leading officials.

These failures contrast with the seriousness of the cases before the tribunal.

For the first time since the postwar Nuremberg trials, almost the entire

leadership of a repressive government faced trial for gross human rights

violations. It offered the chance to create a historical record of some of the

regime's unspeakable rights violations and to begin the process of accounting

for the policies and decisions that gave rise to them. Trials conforming to

international standards of fairness would have been more likely to ventilate and

verify the historical facts, contribute to the public recognition of the

experiences of victims, and set a more stable foundation for democratic

accountability. Instead, unlike the Nuremberg trials, the proceedings have

fallen far short of creating the reference point that could clarify for Iraqis

what happened and why.

The death sentence is a further step away from respect for human rights. The

death penalty, regardless of the crimes involved, is tantamount to cruel and

inhuman punishment. For an Iraq where, one hopes, human rights and the rule of

law will one day be respected, Saddam's punishment is an important benchmark.

The execution order signals the shallowness of the government's commitment to

basic human rights in meting out punishment.

The momentary elation over Saddam's demise among those who suffered under his

regime will not outweigh or outlast the loss of a unique opportunity to

establish a clear record of his regime's criminality. The flawed trial and a

fast-track execution send a clear signal that political interference is still

very much a feature of the judicial process in the new Iraq.

· Richard Dicker is the international justice director of Human Rights Watch

Iraq's shallow justice, G, 29.12.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/story/0,,1979726,00.html

British Soldiers Storm Iraqi Jail, Citing

Torture

December 26, 2006

The New York Times

By MARC SANTORA

BAGHDAD, Dec. 25 — Hundreds of British and

Iraqi soldiers assaulted a police station in the southern city of Basra on

Monday, killing seven gunmen, rescuing 127 prisoners from what the British said

was almost certain execution and ultimately reducing the facility to rubble.

The military action was one of the most significant undertaken by British troops

since the 2003 invasion, British officials said, adding that it was an essential

step in any plan to re-establish security in Basra.

When the combined British and Iraqi force of 1,400 troops gained control of the

station, it found the prisoners being held in conditions that a British military

spokesman, Maj. Charlie Burbridge, described as “appalling.” More than 100 men

were crowded into a single cell, 30 feet by 40 feet, he said, with two open

toilets, two sinks and just a few blankets spread over the concrete floor.

A significant number showed signs of torture. Some had crushed hands and feet,

Major Burbridge said, while others had cigarette and electrical burns and a

significant number had gunshot wounds to their legs and knees.

The fetid dungeon was another example of abuses by the Iraqi security forces.

The discovery highlighted the continuing struggle to combat the infiltration of

the police and army by militias and criminal elements — even in a Shiite city

like Basra, where there has been no sectarian violence.

As recently as October, the Iraqi government suspended an entire police brigade

in Baghdad on suspicion of participation in death squads. The raid on Monday

also raised echoes of the infamous Baghdad prison run by the Interior Ministry,

known as Site 4, where more than 1,400 prisoners were subjected to systematic

abuse and torture.

The focus of the attack was an arm of the local police called the serious crimes

unit, which British officials said had been thoroughly infiltrated by criminals

and militias who used it to terrorize local residents and violently settle

scores with political or tribal rivals.

“The serious crimes unit was at the center of death squad activity,” Major

Burbridge said.

A little over a year ago, British troops stormed the same building seeking to

rescue two British special forces soldiers who had been captured by militants. A

mob of 1,000 to 2,000 people gathered in protest, and a widely circulated video

showed boys throwing stones at a burning British armored fighting vehicle parked

outside the station. The soldiers, who were being held in a nearby building,

were eventually freed.

Although some local officials, including Basra’s police chief, publicly

condemned the action, local residents privately said they were grateful, and

described what they said was an organization widely feared for its brutality.

“They are like savage dogs that bite when they are hungry,” said one resident,

who spoke anonymously for fear of retribution. “Their evaluation of guilt or

innocence is how much money you can pay.”

Residents said that people were afraid to challenge the officers because they

were backed by powerful militia groups, including the Mahdi Army, which is led

by the rebel cleric Moktada al-Sadr, though the extent of his control is

unclear.

“Everyone wants to avoid the mouth of the lion,” one resident said. “From this,

they became stronger and stronger.”

Major Burbridge said that the dismantling of the serious crimes unit had been

planned for months.

As far back as 2004, he said, there was a growing realization that the police

had been widely infiltrated by members of various militias and elements of

organized crime. To combat their influence, the British have been trying to cull

them from the forces in a campaign that began in September.

After trying to determine who was fit to serve in the police, the British began

outfitting trusted officers with sophisticated identification cards meant to

limit the access of impostors to police intelligence, weapons and vehicles.

In late October, gunmen — believed by the British to have been connected to the

serious crimes unit — ambushed a minibus carrying 17 employees of a new police

academy and killed them all. Their mutilated remains were dumped in the Shuaiba

area of the city in an effort to intimidate the local population.

“It had simply gone beyond the pale and it was clear it was time for the serious

crimes unit to go,” Major Burbridge said in an interview.

While they had planned to take over the station on Monday, British forces had to

speed up the operation by several hours. “We received information late last

night,” Major Burbridge said Monday, “that the crimes unit was aware this was

going to take place and we received information that the prisoners’ lives were

in danger.”

More than 800 British soldiers, supported by five Challenger tanks and roughly

40 Warrior fighting vehicles, began their assault at 2 a.m. on Monday. They were

aided by 600 Iraqi soldiers.

The British force faced the heaviest fighting as it made its way through the

city, coming under sporadic attacks by rocket-propelled grenades and small-arms

fire. Of the seven guerrillas killed, six were gunned down as the unit made its

way to the police station.

Upon reaching the station, British troops killed a guard in a watchtower who had

fired on the approaching forces, but there was little other resistance.

The members of the serious crimes unit who had been occupying the building,

several dozen, according to the British military, fled and were not caught. The

British forces turned over the prisoners to the regular Iraqi police, who put

them in a new detention facility.

The two-story building, once used by Saddam Hussein’s security forces, was then

demolished, in an attempt to remove all traces of the serious crimes unit, Major

Burbridge said.

The battle lasted nearly three hours. There were no British casualties, but the

streets around the station were littered with bombed-out cars and rubble.

The violence in Basra, Iraq’s second largest city, is different from that in

Baghdad to the north or Anbar Province to the west, Major Burbridge said.

The killing in Baghdad in recent months has primarily been the result of

sectarian violence, as Shiites have sought to drive Sunnis from mixed

neighborhoods and Sunnis have retaliated. On Monday, at least 10 civilians were

killed and 15 were wounded when a car bomb exploded in the mixed neighborhood of

Jadida.

In northeastern Baghdad, a suicide bomber with explosives tied to his body blew

himself up on a crowded bus, killing 2 people and wounding 20 others.

An American soldier also died Monday in Baghdad in a roadside bomb attack.

In Sunni-controlled Anbar Province, where the fighting is mainly between

insurgents and American troops, two American soldiers were killed in fighting on

Sunday.

In southern cities like Basra, dominated by Shiites, the fighting is a

combination of battles between rival militias vying for power, warring tribes

and organized crime, Major Burbridge said.

“In northern Basra, the fighting is mainly between three warring tribes,” he

said. “The death squads are typically related to political maneuvering and

tribal gain. Then there are rogue elements of militias aiming attacks on the

multinational forces. You throw all those elements into a melting pot and you

get a picture of the complexity of what we are facing.”

British Soldiers Storm Iraqi Jail, Citing Torture, NYT, 26.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/26/world/middleeast/26iraq.html?hp&ex=1167195600&en=b4422a867f23d2af&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Send more troops to Baghdad and we’ll have a fighting

chance

December 24, 2006

The Sunday Times

Frederick Kagan

A decisive moment in world history is at hand.

If the United States, Britain and their allies fail in Iraq the result will

almost certainly be a regional maelstrom. If the coalition succeeds, then the

West will regain the initiative against radical Islam in Iran and throughout the

Muslim world.

The current trajectory in Iraq is poor: rising sectarian violence threatens to

rend Iraqi society and destroy America’s will to continue the struggle.

The choices are bleak: nobody has yet developed a convincing plan to resolve

this conflict through diplomacy, politics or any other form of soft power. Hopes

for success now rest on the coalition’s willingness to adopt a strategy of

bringing security to the Iraqi population and confronting the sectarian violence

directly as the prerequisite for subsequent political, economic and social

development.

Embracing such a strategy would mark a dramatic change from the approach that

the US military has pursued since April 2003. Since the beginning of the

counter-insurgency effort US central command has focused on training Iraqi

soldiers and police to establish and maintain security on their own. America’s

own military efforts to establish security have been reactive, sporadic,

under-resourced and ephemeral.

The creation of an Iraqi army that now numbers more than 130,000 troops is an

impressive accomplishment, but that army has proved unable to stem the violence

on its own. On the contrary, as its size and quality have increased the violence

has grown even more.

Those well versed in the art of counter-insurgency will not be surprised by this

phenomenon, since providing security to the population is a core task for any

counter-insurgent force — as the recently released US military doctrinal manual

on the subject emphasises.

It is now time to abandon the failed strategy of “transition” and return to the

basics of counter-insurgency and stability operations by bringing peace to the

Iraqi people.

Baghdad is the centre of gravity of the struggle in Iraq today. The United

States, the government of Iraq and the insurgents have all identified it as the

place they intend to win or lose. It is also the largest mixed community in

Iraq.

Any hope for keeping Iraq together as a unitary state — thereby avoiding a

genocidal civil and probably regional war — rests on keeping Baghdad mixed.

However, sectarian strife is leading rapidly to sectarian cleansing and many of

Baghdad’s mixed communities are being forcibly purified. Bringing peace to those

areas and ending the violence must be the primary task of coalition strategy.

Establishing security is a military task in the first instance. Troops must move

through Baghdad’s neighbourhoods, examining every house and building, finding

weapons caches and capturing insurgents and armed militias.

American forces have conducted many such operations in the past, including

Operation Together Forward II as recently as the autumn.

In all previous operations the clearing of embattled neighbourhoods was followed

by a rapid withdrawal of US forces. Insurgents of both sects then swarmed back

in to the cleared areas to demonstrate the failure of the exercise by

victimising the helpless inhabitants.

Success in such operations requires persistence. Once a neighbourhood has been

cleared, US and Iraqi forces must remain to maintain security.

Partnered at the platoon or company level, they must live in the neighbourhoods

and man permanent checkpoints. This approach was used with great success in Tal

Afar in September 2005 and thereafter and is being used even now in some

districts of Baghdad.

Units that remain in neighbourhoods rapidly gain the trust of the locals, who

volunteer more information about troublemakers from within the neighbourhood and

interlopers from outside.

The presence of US and Iraqi troops brings greater security, which enables the

start of economic and political development. It is unfortunate that this basic

counter-insurgency approach has been neglected so far, but it is not too late to

undertake it.

Clearing and holding the critical mixed and Sunni neighbourhoods in Baghdad

would require approximately nine American combat brigades, or about 45,000

soldiers. There are now five brigades operating in Baghdad, so America would

have to add four more — about 20,000 soldiers.

In the past, central command generated surges in security in parts of Iraq by

drawing forces from elsewhere. This approach created opportunities for the

insurgents in the denuded areas. It would be wiser instead to couple a surge in

Baghdad with an increase of troops in the other key hotbed of the insurgency,

Anbar province.

There are now the equivalent of three brigades of US troops in Anbar. An

additional two (about 10,000 troops) there would not allow the United States to

clear and hold the province but would prevent insurgents fleeing the fight in

Baghdad from destabilising Anbar further.

It would also place greater pressure on Al-Qaeda and the Sunni Arab insurgency,

whose violent assaults on Shi’ite areas are a principal cause of the growth of

Shi’ite militias.

Military action by itself will not lead to success, of course. The clearing of

neighbourhoods must be accompanied by immediate reconstruction efforts.

These efforts should take two forms. All cleared neighbourhoods should receive a

basic reconstruction package aimed at restoring essential services. But

reconstruction can also be used as a form of incentive.

Neighbourhoods that co-operate with coalition efforts to maintain security could

be rewarded with additional reconstruction efforts to improve their overall

quality of life. These efforts should be channelled through Iraqi local (not

central) government structures as much as possible.

The insurgents, particularly the Shi’ite Mahdi army, have begun imitating

Hezbollah by providing services to the population of Baghdad in return for

loyalty and support.

By offering reconstruction assistance through local Iraqi leaders, the coalition

would get Iraqis used to looking to their own government for essential services.

Combining these efforts with the establishment and maintenance of real security

would reduce the strongest recruiting tools that the Sunni and Shi’ite militias

now have and would make possible future reconciliation and political progress.

The coalition forces can succeed in the end only if they can turn the

responsibility for maintaining security over to the Iraqi forces; the training

of the Iraqi army must also continue.

If a plan of this variety were adopted, in fact, the training of the Iraqis

would improve dramatically. Embedding trainers in Iraqi units is a good start,

but it is not as effective as partnering Iraqi units with coalition troops in

planning and conducting missions.

This plan would also solve another critical problem: instead of presenting the

growing Iraqi army with an ever-increasing security challenge, this strategy

would lower the level of violence even as it expanded the Iraqis’ capabilities.

Such an approach is the only way to make a successful transition to an

independent and secure Iraq.

The increase in US troops cannot be short-term. Clearing and holding the

critical areas of Baghdad will require all of 2007. Expanding the secured areas

into Anbar, up the Diyala River valley, north to Mosul and beyond will take part

of 2008.

It is unlikely that the Iraqi army and police will be able to assume full

responsibility for security for at least 18 to 24 months after the beginning of

this operation.

This strategy will place a greater burden on the already overstrained American

ground forces, but the risk is worth taking.

Defeat will break the American army and marines more surely and more

disastrously than extending combat tours. And the price of defeat for Iraq, the

region and the world in any case is far too high to bear.

Frederick W Kagan is a resident scholar at the

American Enterprise Institute and the author of Choosing Victory: A Plan for

Success in Iraq

Simon Jenkins is away

Send

more troops to Baghdad and we’ll have a fighting chance, STs, 24.12.2006,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2088-2517657,00.html

The betrayal of a soldier: Coroner in blistering attack on ministers at inquest

Published: 19 December 2006

The Independent

By Ian Herbert

The first British soldier to die in combat in

Iraq was killed by friendly fire because of the Army's "unforgiveable and

inexcusable" failure to equip him with body armour, an inquest has found.

Sgt Steven Roberts went into battle lacking "the most basic piece of equipment",

the coroner examining his death concluded. "To send soldiers into a combat zone

without the appropriate basic equipment is, in my view, unforgivable and

inexcusable and represents a breach of trust that the soldiers have in those in

government," concluded Andrew Walker, Oxfordshire's assistant deputy coroner, at

the end of an inquest which uncovered a litany of flaws in Britain's

preparations for the 2003 Iraq invasion.

Mr Walker's damning conclusions further expose a British military struggling

desperately to equip its forces to deal with the occupations of Iraq and

Afghanistan.

Scores of troops have been killed in aged Land Rover vehicles which offer

inadequate protection against roadside bombs, while there is a shortage of

helicopters and doubts about the effectiveness of the SA80 rifle.

The Army is experiencing major recruitment problems - its size has fallen below

100,000 for the first time since the Victorian era - and ministers face

criticism over the poor salaries of troops serving overseas.

Shadow defence secretary Liam Fox said Sgt Roberts' death was "utterly

inexcusable and in a more honourable Government would have resulted in

resignations". He added: "We still hear stories which reinforce the point that

Tony Blair's Government is all too willing to commit our forces to battle

without committing the appropriate resources to our armed forces."

At Oxford Coroner's Court, Mr Walker said he had heard "justification and

excuse" during six days of evidence about Sgt Roberts' death, which has centred

on the army's decision to take back the soldier's enhanced combat body armour

(ECBA) three days before he died because there were not enough of the sets to go

around. "I put these to one side as I remind myself that Sgt Roberts lost his

life because he did not have that basic piece of equipment," he said.

When he died just after dawn on 24 March, 2003, Sgt Roberts, 33, from Shipley,

west Yorkshire was clad in makeshift armour which he had made by stuffing pieces

of padding into his fatigues and sticking them together with black masking tape.

After leaving one of three British Challenger tanks patrolling a vehicle

checkpoint east of Az Zubayr, in southern Iraq, he came under attack from a

stone throwing insurgent wearing white face paint, which seemed to mark him out

as a martyr.

Sgt Roberts'Browning pistol jammed in the dust - as have many others carried by

the British forces. Then, a machine gun in a tank also failed, so the co-axial

machine gun was turned on the Iraqi instead. But the young gunner who fired the

fateful round had not been trained in the use of co-axial. He did not know it

was a long-range weapon which, at short range, hit objects to the left of the

sights - where Sgt Roberts happened to be.

The coroner last week asked former Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon to appear before

him after hearing how the minister delayed for eight weeks before approving a

request for extra ECBA kits in 2002. An MoD director, David Williams, appeared

in the minister's place yesterday and gave evidence which revealed why military

staff working for a Board of Inquiry into Sgt Roberts' death, earlier this year,

had failed to unearth answers about the eight-week delay.

Mr Williams said that an urgent written request for 37,000 extra sets of ECBA,

sent to Mr Hoon by an MoD logistics team on September 13, 2002, was returned by

the minister with the annotation "further advice required" because any approach

to manufacturers would have telegraphed the fact that Britain was preparing for

war while diplomacy continued at the UN.

Mr Hoon finally allowed officials to place an order for the £167 ECBA kits (the

cost is equivalent to two days' pay for an Army private) on 13 November. But the

kits did not reach Iraq until 31 March, 2003 - eight days too late for Sgt

Roberts, who was serving with the 2nd Royal Tank Regiment Cyclops Squadron.

The lack of equipment was exacerbated by the coalition's decision, in January

2003, to invade Iraq from the south, rather than the north. Though an additional

4,000 troops were needed for the southern approach, the combat gear order had

not been increased accordingly. A total of 2,200 troops lacked ECBA kits.

Mr Roberts' widow, Samantha discovered some of these shortcoming when she heard

audio tapes recorded by her husband in the days before his death, describing

preparations as "a joke".She said: "The loss of Steve to us cannot be measured.

This has been the driving force behind our quest for answers, some of which we

feel could have been provided earlier."

The grievances

By Nigel Morris

* Pay/allowances

Levels of pay are a constant grumble, as Tony Blair discovered when visited

Afghanistan last month. Several soldiers told the Prime Minister that a basic

marine, who is paid just over £12,000, could have earned double in the fire

service.

* Recruitment/retention

Levels of recruitment are holding up, but 9,200 left last year before their

period of engagement was up. The armed forces are 5,170 under strength.

* Mental illness

According to MoD figures, 1,897 soldiers have returned from Iraq with mental

health problems, of which 278 have post-traumatic stress disorder, while others

suffer depression, acute anxiety or turn to drink or drugs to cope with their

problems.

* Equipment

The standard-issue army rifle, the SA80 A2, has been dogged by problems,

particularly when salt-water and sand interfered with its mechanism. The rifle

has been upgraded but complaints persist.

* Vehicles

A quarter of British soldiers killed by hostile action in Iraq were travelling

in "snatch" Land Rovers - vehicles designed for Northern Ireland rather than the

arid conditions of Iraq and Afghanistan. They are bullet-proof, but provide no

protection from improvised roadside bombs.

The

betrayal of a soldier: Coroner in blistering attack on ministers at inquest, I,

19.12.2006,

http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/politics/article2086707.ece

Soldier killed because of 'inexcusable' supply delay

December 18, 2006

Times Online

A British tank commander who died in Iraq because he did

not have any body armour was the victim of an "unforgivable and inexcusable"

failure by the Government, a coroner ruled today.

Sergeant Steve Roberts, 33, died manning a checkpoint outside Az Zubayr in

southern Iraq in March. He was killed by friendly fire after a fellow tank crew

started shooting at an Iraqi man who was attacking him with a stone.

A subsequent Army Board of Inquiry found that Roberts would have survived if he

had been wearing standard issue body armour, but he had been forced to hand his

in three days before his death because of the chaotic state of supply to British

forces in the opening weeks of the Iraq war.

Today, Oxfordshire assistant deputy coroner, Andrew Walker, blamed the Ministry

of Defence for leaving around 2,000 soldiers in Iraq without the Army's enhanced

combat body armour, which costs £167 per set.

"To send soldiers into a combat zone without the appropriate basic equipment is,

in my view, unforgivable and inexcusable and represents a breach of trust that

the soldiers have in those in Government," he said, recording a narrative

verdict in the death of Roberts.

"This Enhanced Combat Body Armour was a basic piece of protective equipment. I

have heard justification and excuse and I put these to one side as I remind

myself that Sergeant Roberts lost his life because he did not have that basic

piece of equipment.

"Sergeant Roberts’s death was as a result of delay and serious failures in the

acquisition and support chain that resulted in a significant shortage within his

fighting unit of enhanced combat body armour, none being available for him to

wear."

During the hearing, witnesses, including the former Secretary of Defence, Geoff

Hoon, were called to explain an eight-week delay in late 2002 that caused the

shortage of body armour and other supplies during the invasion of Iraq. The

court also heard recordings made by Roberts for his wife, in which he described

the state of his equipment as "a bit of a joke".

"We’ve got nothing, it’s disgraceful what we’ve got out here. It’s pretty

demoralising," he said.

Speaking after the hearing today, Roberts’s widow Samantha said the verdict and

changes in military procedures would be her husband’s legacy.

"The policy on enhanced combat body armour has changed — this is Steve’s legacy

— but we must ensure that these failures are not repeated with other basic kit.

We have heard from Steve himself, who said it is disheartening to go to war

without the correct equipment."

"The coroner found failing in training and command in the run-up to and after

the shooting, but the single most important factor was the lack of enhanced

combat body armour. If Steve had had that, he would be with us today."

Soldier killed

because of 'inexcusable' supply delay, Ts, 18.12.2006,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,7374-2510786,00.html

Diplomat's suppressed document lays bare

the lies behind Iraq war

Published: 15 December 2006

The Independent

By Colin Brown and Andy McSmith

The Government's case for going to war in Iraq

has been torn apart by the publication of previously suppressed evidence that

Tony Blair lied over Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction.

A devastating attack on Mr Blair's justification for military action by Carne

Ross, Britain's key negotiator at the UN, has been kept under wraps until now

because he was threatened with being charged with breaching the Official Secrets

Act.

In the testimony revealed today Mr Ross, 40, who helped negotiate several UN

security resolutions on Iraq, makes it clear that Mr Blair must have known

Saddam Hussein possessed no weapons of mass destruction. He said that during his

posting to the UN, "at no time did HMG [Her Majesty's Government] assess that

Iraq's WMD (or any other capability) posed a threat to the UK or its interests."

Mr Ross revealed it was a commonly held view among British officials dealing

with Iraq that any threat by Saddam Hussein had been "effectively contained".

He also reveals that British officials warned US diplomats that bringing down

the Iraqi dictator would lead to the chaos the world has since witnessed. "I

remember on several occasions the UK team stating this view in terms during our

discussions with the US (who agreed)," he said.

"At the same time, we would frequently argue when the US raised the subject,

that 'regime change' was inadvisable, primarily on the grounds that Iraq would

collapse into chaos."

He claims "inertia" in the Foreign Office and the "inattention of key ministers"

combined to stop the UK carrying out any co-ordinated and sustained attempt to

address sanction-busting by Iraq, an approach which could have provided an

alternative to war.

Mr Ross delivered the evidence to the Butler inquiry which investigated

intelligence blunders in the run-up to the conflict.

The Foreign Office had attempted to prevent the evidence being made public, but

it has now been published by the Commons Select Committee on Foreign Affairs

after MPs sought assurances from the Foreign Office that it would not breach the

Official Secrets Act.

It shows Mr Ross told the inquiry, chaired by Lord Butler, "there was no

intelligence evidence of significant holdings of CW [chemical warfare], BW

[biological warfare] or nuclear material" held by the Iraqi dictator before the

invasion. "There was, moreover, no intelligence or assessment during my time in

the job that Iraq had any intention to launch an attack against its neighbours

or the UK or the US," he added.

Mr Ross's evidence directly challenges the assertions by the Prime Minster that

the war was legally justified because Saddam possessed WMDs which could be

"activated" within 45 minutes and posed a threat to British interests. These

claims were also made in two dossiers, subsequently discredited, in spite of the

advice by Mr Ross.

His hitherto secret evidence threatens to reopen the row over the legality of

the conflict, under which Mr Blair has sought to draw a line as the internecine

bloodshed in Iraq has worsened.

Mr Ross says he questioned colleagues at the Foreign Office and the Ministry of

Defence working on Iraq and none said that any new evidence had emerged to

change their assessment.

"What had changed was the Government's determination to present available

evidence in a different light," he added.

Mr Ross said in late 2002 that he "discussed this at some length with David

Kelly", the weapons expert who a year later committed suicide when he was named

as the source of a BBC report saying Downing Street had "sexed up" the WMD

claims in a dossier. The Butler inquiry cleared Mr Blair and Downing Street of

"sexing up" the dossier, but the publication of the Carne Ross evidence will

cast fresh doubts on its findings.

Mr Ross, 40, was a highly rated diplomat but he resigned because of his

misgivings about the legality of the war. He still fears the threat of action

under the Official Secrets Act.

"Mr Ross hasn't had any approach to tell him that he is still not liable to be

prosecuted," said one ally. But he has told friends that he is "glad it is out

in the open" and he told MPs it had been "on my conscience for years".

One member of the Foreign Affairs committee said: "There was blood on the carpet

over this. I think it's pretty clear the Foreign Office used the Official

Secrets Act to suppress this evidence, by hanging it like a Sword of Damacles

over Mr Ross, but we have called their bluff."

Yesterday, Jack Straw, the Leader of the Commons who was Foreign Secretary

during the war - Mr Ross's boss - announced the Commons will have a debate on

the possible change of strategy heralded by the Iraqi Study Group report in the

new year.

Diplomat's suppressed document lays bare the lies behind Iraq war, I,

15.12.2006,

http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/politics/article2076137.ece

The full transcript of evidence given to

the Butler inquiry

Supplementary evidence submitted by Mr Carne

Ross, Director, Independent Diplomat

Published: 15 December 2006

The Independent

I am in the Senior Management Structure of the

FCO, currently seconded to the UN in Kosovo. I was First Secretary in the UK

Mission to the United Nations in New York from December 1997 until June 2002. I

was responsible for Iraq policy in the mission, including policy on sanctions,

weapons inspections and liaison with UNSCOM and later UNMOVIC.

During that time, I helped negotiate several UN Security Council resolutions on

Iraq, including resolution 1284 which, inter alia, established UNMOVIC (an

acronym I coined late one New York night during the year-long negotiation). I

took part in policy debates within HMG and in particular with the US government.

I attended many policy discussions on Iraq with the US State Department in

Washington, New York and London.

My concerns about the policy on Iraq divide into three:

1.The Alleged Threat

I read the available UK and US intelligence on Iraq every working day for the

four and a half years of my posting. This daily briefing would often comprise a

thick folder of material, both humint and sigint. I also talked often and at

length about Iraq's WMD to the international experts who comprised the

inspectors of UNSCOM/UNMOVIC, whose views I would report to London. In addition,

I was on many occasions asked to offer views in contribution to Cabinet Office