|

History > 2006 > USA > Immigration (IV)

Editorial

The Fence Campaign

October 30, 2006

The New York Times

President Bush signed a bill to authorize a

700-mile border fence last week, thus enshrining into federal law a key part of

the Republicans’ midterm election strategy. The party of the Iraq war and family

values desperately needs you to forget about dead soldiers and randy

congressmen, and to think instead about the bad things immigrants will do to us

if we don’t wall them out. Hence the fence, and the ad campaigns around it.

Across the country, candidates are trying to stir up a voter frenzy using

immigrants for bait. They accuse their opponents of being amnesty-loving

fence-haters, and offer themselves as jut-jawed defenders of the homeland

because they want the fence. But the fence is the product of a can’t-do,

won’t-do approach to a serious national problem. And the ads are built on a

foundation of lies:

Lie No. 1: We’re building a 700-mile fence. The bill signed by Mr. Bush includes

no money for fence building. Congress has authorized $1.2 billion as a down

payment for sealing the border, but that money is also meant for roads,

electronic sensors and other security tactics preferred by the Department of

Homeland Security, which doesn’t want a 700-mile fence. Indian tribes, members

of Congress and local leaders will also have considerable say in where to put

the fence, which could cost anywhere from $2 billion to $9 billion, depending on

whose estimates you believe.

“It’s one thing to authorize. It’s another thing to actually appropriate the

money and do it,” said Senator John Cornyn, a Texas Republican. “I’m not sure

that’s the most practical use of that money.”

Lie No. 2: A fence will help. A 700-mile fence, if it works, will only drive

immigrants to other parts of the 2,000-mile border. In parts of the trackless

Southwest, building the fence will require building new roads. Who uses roads?

Immigrants and smugglers. And no fence will do anything about the roughly 40

percent of illegal immigrants who enter legally and overstay their visas.

Lie No. 3: The Senate’s alternative bill was weak, and its supporters favored

amnesty. In May, the Senate passed a bill that had a fence. Not only that, it

had money for a fence. It also included tough measures for cracking down on

illegal hiring. It demanded that illegal immigrants get right with the law by

paying fines and taxes, learning English and getting to the back of the

citizenship line. It went overboard in some ways, weakening legal protections

for immigrants and hindering judicial oversight. But it went far beyond the

fence-only approach. Its shortcomings and differences with the House bill might

have been worked out in negotiations over the summer. But instead, House

Republican leaders held months of hearings to attack the Senate bill. And all we

were left with was the fence.

Will the Republican strategy work? We’ll know next week, but we hold out hope

that hard-line candidates are misreading the electorate. Voters all over are

concerned about immigration, of course, but many polls have repeatedly shown

that they warm to reasonable solutions and not to stridency. They can recognize

the difference between the marauding army of fence-jumpers they see in

commercials and the immigrants who have become their neighbors, co-workers,

customers and friends. Citizen anger cuts both ways, and many voters, Latinos in

particular, say they are put off by the Republican hysteria.

Poll results in some races suggest that xenophobia and voter deception are not

necessarily a ticket to victory. In Arizona, Randy Graf, a Republican, is

running for Congress as a single-issue candidate focused on border security,

Minuteman-style. He has said that if his strident argument won’t fly in his

prickly border state, it might not fly anywhere. He is trailing Gabrielle

Giffords, a moderate Democrat who supports the comprehensive approach to

immigration reform endorsed by the Senate and — once upon a time — by President

Bush.

Whatever happens in November, Congress will eventually have to deal with the 12

million illegal immigrants unaffected by the fence, and the future flow of

immigrant workers. That means tackling “amnesty” directly. The sad thing is that

Democrats and moderate Republicans — and Mr. Bush — already did this, and

settled on an approach that is both tough and smart.

But now is the time for stirring up voters, and the pliant Mr. Bush has decided

to go along, adding his signature to the shortsighted politics of fear.

The

Fence Campaign, NYT, 30.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/30/opinion/30mon1.html

Bush, Signing Bill for Border Fence,

Urges

Wider Overhaul

October 27, 2006

The New York Times

By DAVID STOUT

WASHINGTON, Oct. 26 — President Bush signed

into law on Thursday a bill providing for construction of 700 miles of added

fencing along the Southwestern border, calling the legislation “an important

step toward immigration reform.”

The new law is what most House Republicans wanted. But it is not what Senate

Republicans or Mr. Bush originally envisioned, and at the signing, in the

Roosevelt Room of the White House, the president repeated his call for a far

more extensive revamping of immigration law.

A broader measure, approved by the Senate last spring, would have not only

enhanced border security but also provided for a guest worker program and the

possibility of eventual citizenship for many illegal immigrants already in the

country.

But that bill was successfully resisted by House Republicans, who feared a voter

backlash against anything that smacked of “amnesty” for illegal immigrants.

Those lawmakers portrayed the Senate bill as embracing just that, no matter what

the measure’s backers, including Mr. Bush, said to the contrary.

Eventually the president realized that a broad approach was dead for this

election year, and he bowed to political reality and embraced the House concept,

at least for the time being. On Sept. 29, just before its members headed home to

campaign, the Senate approved construction of 700 miles of fencing, which the

House had approved that month.

“I want to thank the members of Congress for their work on this important piece

of legislation,” Mr. Bush said Thursday, greeting several lawmakers by name.

“Ours is a nation of immigrants. We’re also a nation of law. Unfortunately, the

United States has not been in complete control of its borders for decades, and

therefore illegal immigration has been on the rise.”

The new law also provides for more vehicle barriers, checkpoints and advanced

technology to bolster border security. A previously enacted domestic security

spending bill provides $1.2 billion for the fence and the accompanying

technology.

The fence idea has caused friction between the United States and Mexico, as was

demonstrated again Thursday in Ottawa, where the Mexican president-elect, Felipe

Calderón, condemned it.

“Humanity made a huge mistake by building the Berlin Wall, and I believe that

today the United States is committing a grave error in building the wall on our

border,” said Mr. Calderón, who was meeting with the Canadian prime minister,

Stephen Harper.

Some of the legislation’s critics say the fence — actually several separate

sections at a variety of places along the 2,000-mile border — will not keep out

people desperate to cross. A foreign policy adviser to Mr. Calderón, Arturo

Sarukhán, told Canadian reporters on Wednesday that the fence would merely allow

smugglers of illegal migrants to charge them more.

In calling for a broader immigration overhaul, Mr. Bush said again Thursday that

his approach did not amount to amnesty.

“We must reduce pressure on our border by creating a temporary worker plan,” he

said. “Willing workers ought to be matched with willing employers to do jobs

Americans are not doing for a temporary — on a temporary — basis. We must face

the reality that millions of illegal immigrants are already here. They should

not be given an automatic path to citizenship. That is amnesty. I oppose

amnesty.

“There is a rational middle ground between granting an automatic path to

citizenship for every illegal immigrant and a program of mass deportation, and I

look forward to working with Congress to find that middle ground.”

Any such search will almost surely have to await a new Congress. The chance that

it would be taken up in a lame-duck session after the elections is considered

remote.

Christopher Mason contributed reporting from Toronto.

Bush,

Signing Bill for Border Fence, Urges Wider Overhaul, NYT, 27.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/27/us/27bush.html

5 Bodies Pulled From Rio Grande in Texas

October 24, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 11:59 a.m. ET

The New York Times

McALLEN, Texas (AP) -- The bodies of four men

and a woman were found floating in the Rio Grande River in an area known as a

crossing place for illegal immigrants, authorities said.

Mexican authorities notified sheriff's deputies Monday that the bodies were in

the river near the U.S. side, Starr County Sheriff Reymundo Guerra said.

The cause of death was unknown and autopsies were planned.

The bodies, found in a rural area below a dam about 65 miles west of McAllen,

were decomposed and could have been dead for a week, said Carlos Delgado, an

investigator for the Starr County district attorney's office.

No further information was immediately released.

5

Bodies Pulled From Rio Grande in Texas, NYT, 24.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Bodies-Recovered.html

A Shorter Path to Citizenship, but Not for

All

October 23, 2006

The New York Times

By NINA BERNSTEIN

Beverly Lindsay, a Jamaican-born practical

nurse who has made her home in New York for 26 years, filed for citizenship in

June with the help of her union, and prepared for a long wait. After all, as

recently as a year ago, the United States government acknowledged a huge backlog

in such applications, and estimated that processing typically took almost a year

and a half in New York — triple the wait in San Antonio or Phoenix.

But a mere three months and 10 days after Ms. Lindsay applied, she was sworn in

as a citizen. “I’m proud, and I’m happy I’m going to vote in November,” said Ms.

Lindsay, 49.

Her success, however, underscores the frustration of Sophia McIntosh, another

New Yorker from Jamaica who applied for citizenship through the same health care

workers union program three years ago. Not only is she still waiting, but her

case is also now among at least 960,000 immigrant applications pending

nationwide that federal officials have simply stopped counting as part of their

backlog — a backlog they had pledged to eliminate by this month.

“It’s not fair,” said Ms. McIntosh, 34, a nursing assistant and mother of two,

who has been a legal resident of the United States since 1992. “I did all the

right things. I want to be able to have a voice in this country.”

Until recently, the glut of pending cases was so large that President Bush’s vow

in 2001 to cut the standard wait to six months or less nationwide seemed

unreachable. Now immigration officials say they have more than met that goal,

shrinking the average wait to five months for a citizenship decision. And no

district shows more dramatic improvement than New York, where the wait has

officially shrunk to 2.8 months.

But the numbers are not quite as rosy as they seem. To accomplish their mission,

officials at the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services explain,

they identified and stopped counting thousands of backlogged cases that they now

define as outside the agency’s control, mostly those delayed by unexplained lags

in standard security clearances by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The result is a two-tier system. More applicants than ever are receiving a

decision in record time, in part because of an influx of temporary workers

working at the office and new efficiencies. But others are still falling into

the system’s black holes, joining thousands who have been waiting for years, but

are now off the map. While praising the agency’s improvements, immigrant

advocates contend that officials have manipulated the figures to declare victory

and made it harder to seek redress.

Behind the clash over the agency’s new math are anxieties heightened by the

immigration debate and looming elections, advocates and officials said. Legal

residents who lack the security of citizenship feel more vulnerable to

deportation these days and deprived when they cannot vote. And the immigration

agency is under political pressure to show that it can handle any new programs

without derailing old ones.

“Why should we be faulted for sitting on cases that we aren’t sitting on?” asked

Emilio T. Gonzalez, director of Citizenship and Immigration Services, which now

takes responsibility for fewer than 140,000 of the 1.1 million immigrant

applications that it identifies as pending for more than six months.

Mr. Gonzalez added that he would soon seek “significant” fee increases to cover

the costs of processing applications. The agency is losing many of the 1,200

temporary employees who helped speed lagging cases under a four-year

Congressional grant that ended Sept. 30.

But to Laura Burdick, a national deputy director of Catholic Legal Immigration

Network, raising the fees would only compound the inequity experienced by those

who have nothing to show for what they pay — for a citizenship application, the

cost is now almost $400. As for the change in the way cases are counted, she

added, “It makes you just question the validity of any of the information

they’re giving us.”

Data supplied by the government to The New York Times showed some unusual

fluctuations. The New York office, for example, has long had the largest pending

citizenship caseload in the nation, averaging about 100,000 through much of 2004

and 2005. The estimated wait for a decision was more than 16 months in October

2005. But a month later, it dropped to nine months, and 33,240 applications

vanished from the count of pending cases.

Christopher Bentley, a spokesman for Citizenship and Immigration Services, said

a physical inventory conducted for the first time in three years had revealed

that the agency had overcounted its backlog by more than 33,000 cases. “The

really good news is the vast majority of those cases were cases that had already

been completed,” he said.

Temporary workers were deployed to help from as far away as Texas and Nebraska,

Mr. Bentley added, and the remaining caseload in New York shrank to 33,017 by

July. New definitions deducted 10,663 more city cases as being outside the

agency’s control, which cut the estimated wait for the remaining 22,354 to less

than three months. Such calculations have puzzled Crystal Williams, deputy

director of programs for the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

“I really don’t understand why they’re doing this,” she said, “because they have

accurate good news to give: They have improved enormously. But it’s pretty

obvious to anyone who has observed this process for any amount of time that they

are playing with the numbers.”

She added, “All these cases they aren’t counting still have to be adjudicated —

it’s not like they’ve gone away.”

Thousands of applicants are being omitted from the backlog for reasons other

than security checks, usually because the agency has asked for more information,

the applicants are awaiting a second interview or a local court has not yet

scheduled an oath of allegiance.

But delays in conducting security clearances are especially frustrating for

applicants. Lorenzo Zepeda, 38, who immigrated from El Salvador at 18 and worked

his way up from pot washer to head chef at a nursing home in Woodmere, N.Y.,

applied for citizenship almost three years ago.

“We already write, like, 10 letters to them; we never get no answer back,” said

Mr. Zepeda, who is married to an American. The couple are expecting a child in

April. “I really love this country. I want to make decisions in this country.

And I’m paying my taxes like everybody else.”

Also still waiting are a number of Iraqi Kurds who arrived in the United States

a decade ago as political refugees, settled in Nashville and were interviewed by

the F.B.I. before the Iraq war as experts loyal to the United States.

One refugee, Hadi Gardi, 49, says he teaches Arabic and Kurdish to American

soldiers at an Army base in Georgia. He passed background checks for that job,

as he did for earlier ones dating to his work as a translator for Americans in

Iraq. His wife gained citizenship last October. But though he applied when she

did, he is still waiting, told only that the F.B.I. is checking his name.

“I lost so many opportunities,” he said, referring to government jobs that were

open only to citizens. He added that he had made fruitless appeals to his

congressman.

By law, applicants who are not given the citizenship oath 120 days after passing

the interview can seek a court order compelling government action. Such suits

have pushed the authorities to expedite some security name checks that had been

languishing, including cases of elderly and disabled refugees who have to

naturalize within seven years or lose government aid.

But in May, citing national security concerns, Citizenship and Immigration

Services closed off that path by ordering district offices not to hold

interviews until clearances were completed.

Last month, in court papers seeking the dismissal of a federal lawsuit brought

on behalf of stymied applicants in New York, lawyers for the government provided

a rare window into the F.B.I.’s National Name Check Program, giving insight on

why the process can take so long.

The first step involves a computerized search of the F.B.I.’s Universal Index of

94.6 million records for all mentions of a name, a close date of birth and a

Social Security number. Different permutations of the name are tried, like the

first and middle name only. Nearly a third of naturalization cases come back as

having a potential match.

Most of those are cleared up within three months through a search of computer

databases. But in 10 percent of all cases, the possible reference is in paper

records created before automation in October 1995 and in one of 265 possible

locations. F.B.I. analysts must retrieve and review records to see whether the

information actually pertains to the same individual and is derogatory.

“Common names (such as Mohammed, Singh, or Smith) may result in hundreds of

potential matches,” government lawyers wrote. “The sheer volume of the requests

has also resulted in delays.”

Immigration name checks compete not only with those needed for

counterintelligence, but also with a growing number sought by government

agencies before they bestow a privilege, like attendance at a White House

function. Demand has risen drastically, from 2.5 million requests a year before

Sept. 11, 2001, to more than 3.7 million in fiscal year 2005. Among those still

unresolved are more than 400,000 immigrant name checks dating to December 2002.

Still, more recent applications are moving so fast that the citizenship program

at the health care workers union has doubled the size of its annual celebration,

said Celeste Douglass, the coordinator. “People want the safe status of a U.S.

citizen,” she added. “That six-month turnaround is really starting to happen.

Now, how do we get those cases out of the backlog?”

Jo Craven McGinty contributed reporting.

A

Shorter Path to Citizenship, but Not for All, NYT, 23.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/23/nyregion/23citizen.html

NYT

October 18, 2006

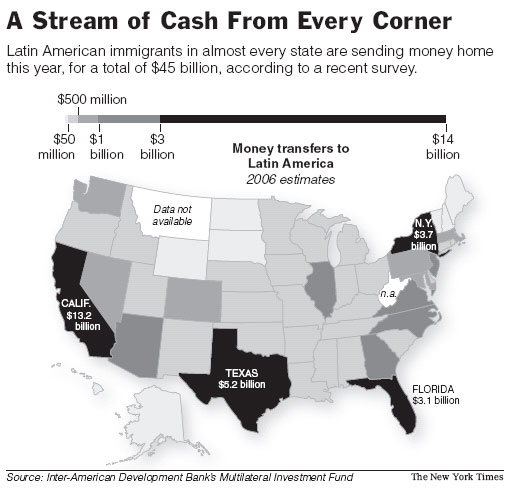

Flow of Immigrants’ Money to Latin America Surges

NYT 19.10.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/19/us/19migrants.html

Flow of Immigrants’

Money to Latin America Surges

October 19, 2006

The New York Times

By EDUARDO PORTER

There is a common cycle to immigration from Latin America.

Immigrants arrive in the United States and quickly find work. Several months

later — in the case of illegal migrants, as soon as they have finished paying

off the smuggler who brought them across the border — they start sending money

home.

According to a new report about immigrants’ money transfers to Latin America,

the remittances flow from almost every state. Even in states that had virtually

no Latin American immigrants only a few years ago, like Mississippi and

Pennsylvania, a growing trickle of money is making its way south to places like

Tlalchapa, Mexico, or Panajachel, in the Guatemalan highlands.

“Twenty years ago the money was coming from four or five states; now it’s coming

from every corner of the country,” said Sergio Bendixen, a Miami pollster who

surveyed some 2,500 immigrants, legal and illegal, for the survey on which the

report was based.

For the nation as a whole, the flow of money has become a torrent. According to

the study, sponsored by the Multilateral Investment Fund of the 47-nation

Inter-American Development Bank, remittances from the United States to Latin

America this year will total more than $45 billion. That is 51 percent higher

than they were only two years ago.

About three-quarters of Latino immigrants who were surveyed send money home

regularly, up from some 60 percent in a similar survey in 2004. This may largely

reflect growth in the population of illegal immigrants, who tend to send money

home more often than others. They accounted for about 40 percent of remitters in

the survey, up from a third in 2004.

Moreover, with immigration to the United States a regular part of the life cycle

for large numbers of men and women in many parts of Latin America, sending money

back to relatives at home has developed into a moral obligation.

“If you don’t send money to your mother, you are a bad son,” Mr. Bendixen said.

“Remittances companies say this in their TV ads.”

The study’s estimates on remittances are in line with population figures from

the Census Bureau, which found last year that Latin American immigrants made up

6.6 percent of the nation’s household population (that is, excluding people in

jail, on military bases and such), more than half the total immigrant

population.

The bureau also found that 1.2 percent of the household population of

Pennsylvania was born in Latin America, as were 0.7 percent of the population of

Ohio and 2 percent of the population of Indiana. These were states with

virtually no Latino immigrants five years ago.

According to the data from the Inter-American Development Bank, money transfers

from Indiana should approach $400 million this year, with the total from

Pennsylvania above $500 million and from Ohio more than $214 million.

Indeed, the study found Latino immigrants sending money from 48 of the 50 states

— excluding only Montana and West Virginia, where, Mr. Bendixen said, he did not

survey because he expected very few remitters.

In addition to those two states, the survey suffers from very small samples in

some with the most recent immigrant populations. But Mr. Bendixen said that in

these states, the remittance figures should be off by no more than 10 percent.

The data are consistent with a known pattern in which Latino migrants move from

immigrant-heavy states like Illinois to new frontiers like Pennsylvania in

search of jobs.

“Somebody who is already here hears about a new plant opening and goes there,”

observed Jeffrey S. Passel, a demographer at the Pew Hispanic Institute. “After

a while, the word gets back to Mexico, and the migrant stream is no longer from

California to a meatpacking plant in Iowa. It’s Mexico to a plant in Iowa.”

The reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina provides an example of

how immigrant populations coalesce around jobs. Latino immigrants have flocked

to New Orleans, where another study has found that by this summer, they

accounted for half the reconstruction force, with 54 percent of them working in

the United States illegally.

They too have begun to send money back. According to the bank’s survey,

remittances to Latin America from Louisiana should top $200 million this year, a

240 percent increase since 2004.

Flow of

Immigrants’ Money to Latin America Surges, NYT, 19.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/19/us/19migrants.html

Border fence to complicate US-Mexico ties: Calderon

Thu Oct 12, 2006 4:38 AM ET

Reuters

MEXICO CITY (Reuters) - A U.S.-Mexico border fence aimed at

keeping illegal immigrants out of the United States will "enormously complicate"

relations between the countries, Mexican president-elect Felipe Calderon said on

Wednesday.

President Bush signed a law last week that will pay for hundreds of miles of new

fences along the border, a move against illegal immigration that Republicans had

sought before next month's congressional elections.

Mexicans are livid about the plan, which is seen as a slap in the face to

efforts during President Vicente Fox's near-completed six-year term to come to

an agreement with Washington on immigration.

"It is going to be a very difficult relationship," Calderon, who takes over from

Fox on December 1, said in a television interview of U.S.-Mexico diplomacy

during his upcoming administration.

"This fence they are leaving me is going to enormously complicate relations with

the United States."

Conservative ruling party candidate Calderon's victory over leftist firebrand

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in the July 2 election was seen as a foreign

relations boost for Washington in Latin America, where anti-U.S. sentiment is

high in some countries.

Border fence to

complicate US-Mexico ties: Calderon, R, 12.10.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=politicsNews&storyID=2006-10-12T083751Z_01_N12174620_RTRUKOC_0_US-USA-MEXICO-CALDERON.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C5-politicsNews-3

In New York Immigration Court, Asylum Roulette

October 8, 2006

The New York Times

By NINA BERNSTEIN

Tears streaked Meizi Liu’s face in 2003 as she told an

immigration judge in New York of being forcibly sterilized in China. The judge,

Jeffrey S. Chase, had won awards as a human rights advocate before his

appointment to the bench in 1995. But now he had 1,000 pending cases, and he had

heard it all before.

He insisted that she was lying, ridiculed her story and, when she would not

recant, denied her petition for asylum.

The tables turned after appeals by Ms. Liu and others reached federal court this

year. In scathing decisions, the court rebuked Judge Chase for “pervasive bias

and hostility,” “combative and insulting language” and remarks “implying that

any asylum claim based on China’s coercive family planning policies would be

presumed incredible.”

It is always judgment day in the windowless courtrooms where immigrants plead to

stay in the United States. But these days, as never before, the nation’s 218

immigration judges are also being judged, even as they struggle to complete

350,000 cases a year amid an immigration debate that promises to send them many

more.

Appeals courts criticize some judges by name, citing abusive behavior and bad

decisions. Studies highlight stark disparities in judgment, like 90 percent of

asylum cases granted by one judge and 9 percent down the hall. Faced with

mounting criticism, Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales vowed to introduce

yearly performance evaluations of the judges, who are Justice Department

employees. The Harvard Law Review urged a campaign to turn the five worst judges

into “media villains” to motivate reform.

Yet a more complicated picture emerges in the federal building in Lower

Manhattan. There, Judge Chase, who colleagues say is chastened since being

rebuked, is one of 27 immigration judges searching for ways to handle 20,000

cases a year, driven as much by scarce resources and escalating demands as by

quirks of personality and power.

In asylum cases, the wrong decision can be a death sentence. In others,

banishment hangs in the balance, with the prospect of families split up or swept

into harm’s way. But before they can consider the merits of a case, judges must

cope with an intricate web of laws, changing conditions in distant lands, and a

mix of false and truthful testimony in 227 tongues vulnerable to an

interpreter’s mistake as small as pronouncing “rebels” like “robbers.”

As the caseload has grown, spurred in part by stepped-up enforcement, so has the

pace demanded by “case completion goals” set in Washington.

To stay afloat, New York judges schedule 30 to 70 cases at a time, hold 4

contested hearings a day and decide more than 15 cases a week, all without law

clerks, bailiffs, stenographers or enough competent lawyers.

“The court is a stepchild of the whole immigration system,” said Sandra Coleman,

who spent years on the immigration bench in Miami. “They want to make the judges

the villains, and there are judges who are villains, I don’t deny that. But the

problem is the system.”

Many federal judges agree. “I fail to see how immigration judges can be expected

to make thorough and competent findings of fact and conclusions of law under

these circumstances,” John M. Walker Jr., chief judge of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Second Circuit, told the Senate Judiciary Committee in April,

urging that the number of immigration judges be doubled.

With one of the largest caseloads among the nation’s 53 immigration courts, and

with nearly half its cases concerning asylum, New York illustrates the crunch

that judges face in many big cities where complicated matters crowd the docket.

Caseloads exploded in the 1990’s. In 2000, an unpublished report by a Justice

Department evaluation team warned that New York judges were “reaching the point

of exhaustion and burnout.”

The report urged a slower pace and an increase in the staff-judge ratio to three

to one from two to one. Instead, an evaluation last year found that the ratio

had slipped even lower.

Justice Department rules do not allow immigration judges to speak to reporters.

But weeks of observation, court records and interviews with lawyers, clerks,

interpreters and immigrants show that the judges are coping in very different

ways, with far-reaching consequences.

Patricia Rohan, who keeps a twinkling Statue of Liberty lamp in her chambers, is

recognized after 24 years on the bench as a model of soft-spoken fairness and

efficiency.

On a recent weekday, with 575 cases pending, she patiently took notes as a man

who shells fish explained why deportation to Gambia would put his Bronx-born

daughters at risk of genital mutilation. She gently questioned an Ecuadorean

cleaning woman of 55 who avowed that love, not a green card, had prompted her

marriage to an American 15 years after she immigrated illegally. Teasing out

supporting evidence in both cases, Judge Rohan dictated favorable decisions into

an aging tape recorder.

Other judges have a different approach. Sandy K. Hom, appointed in 1993, is also

invariably polite, but so quick and predictable in his denials of asylum — 91

percent in recent years, compared with Judge Rohan’s 25 percent — that lawyers

regularly advise people assigned to him to move to another state.

Given his speed, he has the fewest pending cases, about 345. But many of his

decisions have been rejected on appeal, including one in which he denied asylum

to a widowed Armenian Christian and her children and ordered them deported to

Iraq, arguing that since Saddam Hussein’s ouster, they had no reason to fear

religious persecution.

In another case, records show, he mixed up the medical documents presented by

Janeta Kutina, a 69-year-old Latvian woman of Jewish heritage, confusing the

deaths of her father and her husband, both victims of anti-Semitic violence.

Then, the appeals court found, he cited his own mistake as evidence that her

account was inconsistent.

Down the hall and at the other end of the spectrum, Margaret McManus grants

asylum at the highest rate in the country — 90 percent — but at the price of

what Kevin Kerr, president of the clerks’ and interpreters’ union local,

complains is a chaotic calendar with 931 pending cases. She typically

reschedules cases until petitioners can secure supporting documents, pursue

other avenues or find lawyers.

A judge’s fact-finding is much harder without a lawyer to speak for those facing

deportation, who are not entitled to court-appointed counsel. Many get what the

2000 Justice Department report called “the high-volume, low-margin, piecework

approach” practiced by “an unsavory subculture” of “travel agency” lawyers. Nor

do government lawyers know each case.

Judge Chase’s trajectory illustrates why those judges unable to come to terms

with the system’s deficiencies may risk losing their judicial bearings.

As a young immigration lawyer, he joined rallies on behalf of Chinese

asylum-seekers and gave other lawyers videotaped lessons on asylum.

“Some of the judges will have their minds made up before they enter the

courtroom, depending on the country an immigrant is from,” Mr. Chase, whose wife

immigrated from Iran, told a Newsday reporter in 1995. “A judge needs to start

each case with a clean slate and listen to the lawyer and the applicant. Rather

than have that look on his face of ‘Why are you wasting my time?’ ”

But before long, incredulous tirades became his trademark in many Chinese asylum

cases, according to court records and interviews with a dozen lawyers. Openly

frustrated with a pattern of boilerplate claims that he suspected had been

concocted by smugglers, he applied his own tests of honesty.

In September 1999, at the first court appearance of Guo-Le Huang, who said his

wife had been forced to have an abortion in her last month of pregnancy, Judge

Chase rejected the man’s assertion that he was not working because he lacked

papers.

“That is the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard,” Judge Chase said, setting

the tone he would take with Mr. Huang over two years. “I’m not going to waste my

court time on this case.” He questioned why Mr. Huang lived in a Hispanic

neighborhood, interrupted an account of persecution with sarcasm and berated him

for giving up his firstborn for adoption because she was a girl, calling the act

“sexist” and “inhumane.”

In the harried world of immigration court, many lawyers seemed to accept his

tactics as an idiosyncratic tool, not unlike the long wooden claw that another

judge, lacking a clerk, uses to hand down documents. And, statistics show, Judge

Chase granted 42 percent of the 2,729 asylum requests he heard through 2004,

including 250 of 943 from China.

“He’s trying very hard to get to the truth,” said one lawyer, Robert Murtha. “A

lot of these people, if you look behind the foolish lies they’re telling, they

really do have a case. But the lawyer that they go to adapts their story to

conform with the pattern, and it does drive him crazy.”

Another lawyer, Peter Lobel, described Judge Chase as a “deeply caring man,”

whose approach was “ ‘I don’t care what your claim is, just be honest with me.’

” But he added, “He got so it was like an interrogation.”

Several lawyers credited Judge Chase with unusual generosity to petitioners who

admitted to falsehoods — no help to those who maintained they were telling the

truth. Ms. Liu, now 39, the asylum-seeker who told of being forcibly sterilized,

testified that family-planning cadres in China subjected her to painful uterine

surgery when her second child was a baby. She fled in 2000, leaving her children

in hopes of reunion in America.

“The judge said, ‘You have been lying all day, but if you admit to lying, I will

grant your case,’ ” Ms. Liu recalled through an interpreter. “I was very angry,

because everything I said was true.”

In 2003, she appealed his denial to the Board of Immigration Appeals, the

internal review body. But a year earlier, its reviews had been sharply curtailed

when John Ashcroft, then attorney general, cut board membership to 11 from 23

and set tight deadlines to reduce a large backlog. Single board members issued

50 decisions a day, typically one-sentence rulings affirming denials.

Like Ms. Liu, many of those who received such decisions turned to federal court.

Second Circuit filings jumped 53 percent; it is finding merit in 20 percent of

the immigration appeals, returning them for revision.

Ms. Liu’s case was remanded in February, and lawyers say Judge Chase tried to

change. But in July, the 2001 Huang case caught up with him, in a blistering

Second Circuit decision prominently published in The New York Law Journal.

Mr. Lobel described the judge as devastated and braced for more: “He said, ‘I

learned my lesson, but some of these cases are still in the pipeline.’ ”

Ms. Liu is still waiting, too, and worrying about which judge will decide her

family’s fate.

In New York

Immigration Court, Asylum Roulette, NYT, 8.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/08/nyregion/08immigration.html?hp&ex=1160366400&en=c7e37797967e85fc&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Bush signs bill paying for new border fence

Wed Oct 4, 2006 10:55 PM ET

Reuters

By Steve Holland

SCOTTSDALE, Arizona (Reuters) - President George W. Bush

signed a law on Wednesday that will pay for hundreds of miles of new fences

along the U.S.-Mexico border, a move against illegal immigration that

Republicans had sought before next month's congressional elections.

Bush had hoped to address the illegal immigration issue in a comprehensive way

that would have brought beefed-up border security as well as a temporary

guest-worker program allowing immigrants to work legally in the United States.

He spent months advancing the idea but failed to overcome doubts from many

Republicans on Capitol Hill who derided the guest-worker program as an "amnesty"

that would give illegal immigrants a route to citizenship.

Under the legislation, about $1.2 billion would be spent during the fiscal year

that began October 1 for southwest border fencing and other barriers. The money

is part of a $33.8 billion package for domestic security programs that are being

bolstered following the September 11 attacks.

An estimated 12 million illegal immigrants live in the United States, many of

whom entered through the porous border with Mexico.

Mexico had strongly objected to the fence, which it saw as a slap in the face to

efforts during President Vicente Fox's nearly completed six-year term to

negotiate an agreement with Washington on immigration.

Mexico's Foreign Minister Luis Ernesto Derbez said the fences hurt bilateral

relations. "Just the idea of a wall, a fence ... is an insult to good

neighbors," he told a news conference on Wednesday.

President-elect Felipe Calderon said fences were not the solution to the illegal

immigration.

"It does not resolve the problem and, I insist, it will make many Latin

Americans take bigger risks, probably causing deaths," Calderon said on a visit

to Colombia.

Republicans, hoping to hang on to control of the U.S. Congress in November 7

elections, have been pushing border security in reaction to anger by voters, who

say in some places immigrants are taking away jobs and swamping health and

education services.

In a signing ceremony in Arizona, where illegal immigration is a grave concern,

Bush said he still wanted a guest worker program to relieve pressure on the

border with Mexico.

"The funds that Congress has appropriated are critical to our efforts to secure

this border and enforce our laws. Yet we must also recognize that enforcement

alone is not going to work. We need comprehensive reform that provides a legal

way for people to work here on a temporary basis," Bush said.

The legislation will also fund increased nuclear-detection equipment at U.S.

ports and raise security standards at chemical plants.

(Additional reporting by Tabassum Zakaria and Tomas Sarmineto in Mexico

City)

Bush signs bill

paying for new border fence, R, 4.10.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=politicsNews&storyID=2006-10-05T025528Z_01_N04413066_RTRUKOC_0_US-USA-IMMIGRATION-BUSH.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C5-politicsNews-2

Shelter From the Storm

October 1, 2006

The New York Times

By JOHNNY DWYER

SHORTLY after 1 a.m. on a drizzly July night, Hadrick and

Abraham Julu, two trim brothers from Liberia, stared at the door of Room 214 of

the Westway Motel in East Elmhurst, Queens, and then at each other. Hadrick, who

held the room’s key card in one hand and the skinny forearm of their ailing

father in the other, jiggled the door’s handle, but it would not budge. The

brothers had never seen a door that worked this way. But they kept trying,

mindful that eight of their siblings, the youngest of them 12, were waiting

slumped and exhausted on benches in the lobby.

Eventually, the Julus managed to enter their rooms, and they did so with great

relief. Twenty-five hours had elapsed between their departure from a refugee

camp in Ghana and their arrival at the Westway Motel, a pair of low-rise,

khaki-colored buildings just west of La Guardia Airport.

The Julus’ journey had been full of dazzling, sometimes disturbing firsts: the

family’s first airplane flight, their first moments in America, the first time

they ate three meals in a single day. Most important, the trip was the first

time that the family, which had fled war-torn Liberia in 1989, had moved from

one country to the next without being in danger.

But for the Westway, the Julus’ arrival represented business as usual. For 21

years, the 122-room motel has been the initial stop in a new life for that most

desperate category of immigrant: the refugee fleeing war or persecution. The

Westway, where refugees stay overnight before beginning the next leg of their

journey to safety, is one of only eight motels nationwide that serve this role,

and the only one in New York. For these motels, the most important day of the

year comes in early autumn, when the president sets the exact number of refugees

that will be admitted to the United States in the following 12 months.

This year, the day is imminent. On Wednesday, a State Department official

testified before a Senate subcommittee that President Bush had proposed a 2007

ceiling of 70,000 refugees, the same number authorized for the 2006 fiscal year.

On Friday, a spokesman for the State Department, Peter Eisenhauer, said that the

final proposal had just been forwarded to the White House for the president’s

signature.

For the countless refugees worldwide clamoring for entry to America, this number

is critical. But it does not even hint at the deep joy felt by the individual

refugee who, after long trial and tribulation, has finally found a haven in

America.

“When the flight landed,” said Hadrick, 20, weary but smiling broadly on that

night in Room 214, “I was like, ‘Wow!’ ”

Later, he added, “Every breath is a beginning.”

Ellis Island on the Grand Central

A modest red sign along the Grand Central Parkway reads “Westway Motel,” and it

may be the only beacon to this singular institution. The motel, which abuts the

parkway and sits opposite St. Michael’s Cemetery, is easy to miss. Its small

buildings are only three stories high, barely registering among the private

homes and apartment complexes in a working-class, ethnically mixed neighborhood.

Guests trickle into the Westway throughout the day. Not all are refugees. Among

them are delayed travelers, weary truckers, and couples whose baggage consists

of little more than a six-pack and a shared look of expectation. A room rents

for $111 for the night, though what the motel tactfully describes as “short

stays” are available for less.

The Westway, which was built to serve airport business, opened in the early

1960’s, but only in 1985, at the request of the International Organization for

Migration, did it begin to house refugees. That agency, created in 1951 by the

United States and some allies to cope with refugees from World War II, arranged

for the motel to furnish rooms for people needing a way station en route to more

permanent settlement.

“The Westway is like the Ellis Island of years ago,” said Barbara Letizia, a

desk clerk who began working at the motel a few years before the first refugees

checked in. But unlike arrivals at Ellis Island, the immigrants entering the

Westway are exclusively refugees — although Westway staff members refer to them

as “I.O.M.’s,” after the agency that handles their travel arrangements. Between

1990 and this past July, an estimated 170,000 refugees, nearly one-quarter of

the 700,000 refugees who passed through Kennedy Airport during that time, have

spent a night at the Westway.

At first glance, the lobby looks like that of any motel slightly past its prime.

Two pay phones and four vending machines line the walls. On the window of the

desk clerk’s office is a gold-lettered placard that reads, “Cigarettes for

Sale.” But below that notice is a less familiar sign: it tells guests where they

should leave their bags — in Cyrillic letters. That is not surprising; most of

the refugees at the Westway do not speak English.

In many respects, the Westway lobby is a time machine, where political

cataclysms from decades long past still reverberate. The Julus’ journey, for

example, began with the brutal civil and tribal wars that raged in West Africa

during the late 1980’s and the early 90’s; other recent arrivals were uprooted

by the disintegration of the Soviet Union around the same time.

“I’ve had the Vietnamese boat people, Armenians, the Polish, Iranians, the

Russian Jews, the Africans,” said Alex Beskrownyj, the I.O.M. operations manager

at Kennedy Airport for 25 years. “And of course, after they opened the borders

for the Soviet Union, we started getting the Ukrainians.”

By the time a family of refugees have passed through the motel’s glass doors,

they have typically reached the end of a long bureaucratic road. Not only must

they pass rigorous screenings by the Department of Homeland Security and the

Department of State, but the resettlements they seek are pretty much a last

resort.

“We’re trying very hard to bring in people who have a real need, that they’ve

been enduring a situation that seems to have no solution,” said Theresa Rusch,

admissions director of the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and

Migration.

The preferred solution for refugees is repatriation, but often that is

impossible for one of two reasons. Some, like the Hmong people of Laos, are

stateless; no country recognizes them as citizens. For others, like the Julus, a

homeland still exists, but to return would bring danger, possibly death.

“Some people are afraid to go back to Liberia because, one, they don’t have

anything; two, they are being hunted,” Hadrick Julu said. “Like in our case,

those who drove us out of our country, they are still alive.”

Even those who clearly qualify as refugees are lucky to make it to America. The

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that there are 9.2

million refugees worldwide, meaning that the number of admissions proposed by

the Bush administration for 2007 is comparatively minuscule. Moreover, because

of heightened security policies and limited funds since 9/11, fewer refugees

have been admitted than even the low ceilings have allowed. In the 2005 fiscal

year, for example, though the official ceiling was 70,000, the State Department

could afford to accommodate only 54,000 arrivals, and in the fiscal year that

ended yesterday, the number of arrivals was only about 41,000. Nonetheless, the

United States’ resettlement program is the largest of any country.

The Westway, Dusk to Dawn

A day at the Westway begins, and ends, with refugees on the move. In the

afternoon, flights arrive from places like Nairobi, Riyadh and Moscow, and

within an hour or two the I.O.M. has delivered some of those passengers to the

motel door. Early the next morning, those same guests depart, on their way to

new homes in Oklahoma City, Minneapolis, Boston — wherever.

“This is their first lifeline,” said Ms. Letizia, the desk clerk. “They come

here. They eat. They sleep. Then the next morning, they just disperse all over

the country.”

On a slow day, only a single refugee family might arrive at the Westway, but in

an average week, more than 200 refugees will check in. Mohammad Rasouly, an

I.O.M. employee who has been squiring refugees in and out of the Westway for 15

years, does not need a log-in sheet to count the arrivals. “I know who is a

refugee,” he said. “I can separate them from a regular person. By face. By

bags.”

The evening the Julus checked in, Mr. Rasouly sat in the motel’s lobby awaiting

more of the day’s arrivals. A 48-year-old Afghani, Mr. Rasouly usually greets

guests wearing a vest sporting his agency’s logo — a soft blue globe framing a

man, a woman and a child. The logo is seen all over the Westway, on things like

the name tags the refugees wear and the small plastic bags in which they carry

their travel documents.

To Ms. Letizia, sitting at the front desk, the refugees look confused, tired and

disheveled. But not always.

“We did have one family that stands out — they had 13 children,” said Ms.

Letizia, recalling a young Russian mother. “She had another one on the way. She

had a little tribe. They were all in line, in order, clean, well dressed. It was

amazing. They were like steps: one blond, blue-eyed after the other.”

Sometimes the refugees arrive strikingly unprepared. “During the winter there

have been people that come in here with barely anything on them for winter

clothes,” said Renee Weinberg, the motel’s manager. “So we’ve gone out to stores

to get them socks and jackets, and given them stuff that we had from other

donations.”

Ms. Letizia recalled a young boy who simply did not want to live in the United

States. “When the van stopped, he ran away,” she said. “But when we got him

back, he ate his food, then the next day it was over and done with.”

With old people, the solutions are more elusive. “The sad reality is, they wait

for forever to get here, and they bring their elderly parents,” Ms. Letizia

said. “And some of them are in their 90’s. They’re going to die here and not at

home. You can see the sadness in them.”

Ms. Letizia’s grandfather emigrated from Italy around World War I and built the

home in Queens that her parents still live in.

“I come from here and I struggle,” she said. “I don’t know how they do it.”

Family Without a Country

Shortly after 5 p.m. on the day the Julus arrived, a van carrying three other

families pulled into the motel parking lot. All were Meskhetian Turks, an ethnic

group that Stalin had deported from Georgia to Uzbekistan more than a half

century ago.

Mr. Rasouly, the I.O.M. official, strode out to meet them, instructing the men,

in Russian, to wait for their luggage, and then leading the women into the

lobby.

A half-hour later, one of the three families, the Ibragimovs, rested in a room

overlooking the motel’s parking lot. Makhamad Ibragimov, the father, finished

off the Styrofoam container of chicken and rice that a Westway porter had

brought to him; the mother, Aziza, did not touch her food. Their three sons,

ranging from 12 to 21 years old, sat and listened intently as their father

recounted the details of their journey.

Unlike the Julus, the Ibragimovs are stateless. As Mr. Ibragimov describes their

situation, he and his wife were born in Uzbekistan and were citizens of the

Soviet Union, but after its dissolution in 1991, they fled to Russia to escape

violence against Meskhetian Turks. Then, because Russia denied citizenship to

their ethnic group, the family moved to Belgrade. A decade later, the family

returned to a region in southern Russia called Krasnodar, but since they were

not Russian citizens, they were unable to work. And so they became refugees.

After dinner, Mr. Ibragimov’s sons drifted out into the motel parking lot. As

traffic streamed by on the Grand Central, a banana yellow Ford Mustang

convertible turned into the entrance, and the driver raised the car’s top. The

brothers smiled. They were in America.

The next morning, the family would travel to Charlottesville, Va., where they

would be reunited with Mrs. Ibragimov’s parents and sister, and begin their new

lives.

“We know why we choose America,” Mr. Ibragimov said. “We lived in a Muslim

country. We were Muslim, but they were Muslim, too, and they didn’t let us to

live there. But we know how many nationalities, how many different religions,

live in America.”

Palm Butter and Prayer

Room 214, where three members of the Julu family spent their first night in

America, was a tidy, spare space with off-white walls and floral comforters on

the two queen beds. On the outlets were childproof plastic plugs, a precaution

for guests unfamiliar with electricity. By comparison, at the family’s previous

home, the Buduburam Refugee Settlement in Ghana, the floors were dirt, the beds

mats, the only light came from a single kerosene lamp, and the bush served as

the bathroom.

But not all the changes were for the better. “Especially on the flight, the

food,” said Hadrick, referring to the rich meals of chicken and fruit juice. “I

wanted to vomit.”

Their father, Kporkwehyea, though only 53, is gaunt and frail and suffers from

congestive heart failure. “He took the sickness during the war,” Hadrick said.

“He was stabbed with a knife. By rebels.”

The war in Liberia had torn into the Julu family, leaving two uncles and an aunt

dead, and sending the father and sons into the bush and a 16-year exile.

Although they sought refuge in the Ivory Coast, the war quickly followed them

there. In 1995, they arrived at Buduburam, a sprawling camp that was home to

42,000 refugees. There, by gardening and making bricks, they survived on barely

$2 a day.

Last December, the family applied for resettlement in the United States. Because

another brother and sister had been resettled in Boston previously, the

remaining relatives were eligible for resettlement under the principle of

“family reunification.”

The family’s departure was set for July 27. On their last night in the camp,

they had a celebratory meal of cassava leaves, palm butter and fufu, a

traditional West African dumpling. “During that little gathering,” Hadrick said,

“we pray because we are Christians.”

Prayers were the one constant on their journey to America. Before dawn on the

day of their flight, the Julus prayed with friends and relatives in the refugee

camp parking lot. They prayed as their plane taxied down the runway at the

airport in Ghana, and as it pushed through the clouds approaching New York.

After putting their father to bed that night at the Westway, Abraham and Hadrick

Julu knelt before their bed in Room 214, and prayed again.

•By late September, the Julus had been settled in a Boston suburb. The father,

who had been hospitalized, had been released and was on the mend.

But the fears that haunt refugees followed Hadrick north. He had heard about the

Big Dig, Boston’s troubled highway tunnel construction project, and about the

recent collapse of part of its roof. When he rides in a car, he worries about

something happening. “Each time when I was traveling through tunnels,” he said,

“I feel so afraid.”

The family now lives in a four-room apartment in the town of Malden, Mass. The

younger children have entered high school; the older ones are looking for jobs.

The Julus have found a nearby church, the Church of the Nazarene in Malden,

where they can worship.

Hadrick is exploring his chances of attending Bunker Hill Community College in

Boston. In speaking with college officials, he is learning about “student loans”

and “financial aid” — new words for his new life in America.

Shelter From the

Storm, NYT, 1.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/01/nyregion/thecity/01west.html?hp&ex=1159761600&en=01da4dcf3c22d047&ei=5094&partner=homepage

|