|

History

> 2006 > USA > African-Americans

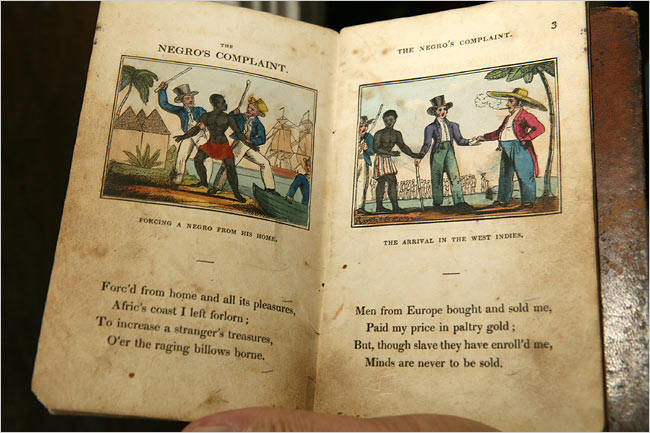

An early-19th-century edition of "The

Negro’s Complaint"

is among the collection’s thousands of rare books.

Marissa Roth for The New York Times

NYT December 13, 2006

Black History Trove, a Life’s Work,

Seeks Museum

NYT

14.12.2006

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/14/

arts/14clay.html

Obituary

James Brown

Godfather of Soul

became a spokesman for black

America

Tuesday December 26, 2006

Guardian Unlimited

Stocky but lithe, like a street-brawling puma,

James Brown, who has died aged 73 of congestive heart failure, was a dominant

force in the emancipation of African-American music and culture from the 1960s

onwards.

He was still performing up to his death. The

day before he was hospitalised for pneumonia, he was at his annual Christmas toy

giveaway in Atlanta, Georgia, and looking forward to giving a New Year's Eve

concert.

Not that Brown was ever comfortable with such a politically correct notion as

African-American. He was first and foremost of, and for, the US. Secondly, he

remained defiantly a southerner. And, although he was unashamedly black, he had

a lot more Cherokee Indian and, by his own admission, Mongol blood in him than

any special connection or empathy with Africa - despite being hailed as some

kind of homecoming hero when touring that continent. Latterly he saw himself as

Universal James.

From the degradation and apparent hopelessness of an apparently stillborn

delivery in a rural shack in the segregated southern US - he was resuscitated

only when it was noticed that his body had stayed warm - he fiercely drove

himself to become an internationally renowned, massively influential icon of his

own invention, the Godfather of Soul.

Like other sobriquets - the Hardest Working Man in Showbusiness was an earlier

claim, Minister of New Super Heavy Funk a later pitch - GOS was OTT, but it was

the one that stuck and most befitted the nature of the man and his Taurean

charge at life.

His career thundered or faltered more in accordance with the strengths and

pitfalls of his relentless ego and determination to be somebody than any

believable script. The fallout of his monumental drive "to the bridge" is a

persistently resonating pulse that informs the dance of opportunity for all of

us, of any creed or colour.

Brown's professional recording career lasted more than 40 years, but it was the

decade from 1965 to 1974 that circumscribed his most extraordinary achievements.

During that turbulent era of civil rights upheaval and war in Vietnam, he

exploded from the launch-pad of "chitlin circuit" stardom (named after the

characteristic dish of boiled pigs' intestines), playing the chain of "safe"

black venues in the south and east, to become a national spokesman for black

America.

By then independently controlling his own affairs, he hob-nobbed with politicos

and cultural luminaries, was feted by the White House and was credited with

helping greatly to calm the streets immediately following the assassination of

Martin Luther King on April 4 1968. He bought three of the then five black-owned

US radio stations, launched his own soul food restaurants and food stamps

programme, entertained in Africa and for US troops in Vietnam. He commanded

attention. He was on an unprecedented, socially provocative roll while all the

while maintaining a punishing schedule with his frenetic stage show.

By the mid-1970s, his political and business naivety had backfired. Nonetheless,

it was during those 10 years that he and, just as importantly, the changing

ensembles of talented musicians he employed, inspired and bullied, created music

that was challenging, exhilarating, fuelled with passion and a rhythmic

intensity unlike anything before. Of the moment and of the man, it is a

substantial legacy of work that remains wholly idiosyncratic and yet is

repeatedly echoed around the globe.

A later defining moment in Brown's career came in January 1986, when he was

inducted as one of the 10 charter members into the US music industry's Rock 'n'

Roll Hall Of Fame. The other worthies were either dead or well beyond their

"best before" date. Brown was concurrently riding his biggest international hit

for more than a decade (Living In America, appropriately soundtracked in the

bullish movie Rocky IV) at the very time his back catalogue was being plundered

by an entire new international generation.

Few bravehearts have attempted to replicate organically a James Brown recording

as he and his musicians spontaneously created them. But with the advent of

computerised sampling technology, all and sundry were suddenly able to swipe his

card into a soundtrack for their own aspirations. The beats and rhythms, screams

and hollers; the energy and badassness; the catharsis and charisma; the

unorthodoxy; all there for the taking. What Brown had emoted as personal

expression came back around as a worldwide display of scattershot sound bites.

Whether later disciples from Tokyo to Tooting Bec fully understood where James

Brown was coming from in the first place is another matter entirely. He wasn't

always entirely lucid on that score himself.

Brown was born in the pine woods outside Barnwell, South Carolina, to parents

who soon separated, leaving him in the care of an "aunt" who ran a brothel

across the Savannah river in nearby Augusta, Georgia. A raggedy-assed waif with

limited education but street nous, his early focus on sport and music was

interupted by four years in jail for petty theft.

Paroled in 1952 in Toccoa, Georgia, he was taken in by the Byrd family,

initially "wrecking the church" as a fervent gospeller with Sarah Byrd (an

innate gift he later parodied in the 1980 movie, The Blues Brothers), then

joining brother Bobby Byrd's group, the Gospel Starlighters. With their secular

heads on, known as the Avons, they bounced from the early inspiration of Louis

Jordan and His Tympany Five to perform the jump-jive of Joe Turner, Roy Brown

and Wynonie Harris, the closeknit harmonies of groups like the Ink Spots and

Orioles, and the newly emergent rhythm and blues sounds of Billy Ward's

Dominoes, Clyde McPhatter and The Drifters, The Clovers and suchlike. Byrd's

Avons became the Famous Flames with Brown at the forefront and relocated to

Atlanta, Georgia, in pursuit of local tearaway Little Richard.

In late 1955, Richard had a hit with Tutti Frutti and decamped to Los Angeles

for an incandescent, if brief, eruption of some of the greatest rock and roll

records ever made. Brown temporarily emulated Richard on stage, but eschewed

rock and roll when it came time for the Famous Flames to record in February

1956. Instead they cut a tortured, gospel-derived personalisation of an Orioles

version of the Big Joe Williams' blues, Baby Please Don't Go. They called it

Please, Please, Please. Syd Nathan, the myopic owner of Cincinnati-based King

Records, to whom they were signed by the producer Ralph Bass, called it "the

worst piece of shit I ever heard", but released it anyway. It has sold millions

over the years and remained Brown's cape-flourishing, knee-dropping homage to

his past throughout his career.

Despite their initial territorial success, Brown and a changing vocal group

struggled in southern obscurity until a second hit in late 1958 (Try Me, a more

romantic supplication) convinced Ben Bart, the owner of Universal Attractions

booking agency, to become Brown's personal manager, business mentor and

surrogate "pops". Recruiting his first small band of regular musicians, and with

his teeth, hair and wardrobe made over, by 1962 Brown was breaking box office

records in major black venues throughout the US with a whirlwind revue of his

own creation that synthesised all of his roots into a shockingly unique new

persona. Live at the Apollo,the resulting LP recorded at the top New York venue,

smashed him into the face of white recognition.

What followed did not go according to anybody's plan. Brown formed his own

independent company, Fair Deal Productions, and rebuilt his band into a sizeable

orchestra with the intention of crossing the tracks at Tuxedo Junction. The

prevailing social climate in the US, Brown's responses to the situation, and the

fact that his new recruits were mostly restless young jazzers, sparked them all

off into uncharted territory. It was Out of Sight, Papa Got a Brand New Bag. A

Man's World bathed in Cold Sweat. He Said it Loud, was Black and Proud and

danced the Popcorn. In a New Day it was Funky Now. He was Super Bad, a Sex

Machine with Soul Power. He had his Thang and Papa Didn't Take No Mess, he

demanded Payback. This litany of just a few of his more familiar titles does

little justice to the underlying tour de force, involving three effectively

different bands over 10 years, that changed the direction of black American

music.

By 1975, James Brown was showing the first signs of insecurity since the 1950s.

In the charts he was being outflanked by many of the younger acts he had

inspired, he was on shaky ground with his record company, Polydor (a

dispassionate international corporation, unlike the seat-of-the-pants operation

with which he had grown strong), some of his leading musicians left him, and the

Internal Revenue Service was on his case.

It was then that he apparently began smoking something rather more confusing

than the occasional menthol and began rehashing his old hits; following trends

instead of creating them. Nevertheless, he soldiered on, still toured the world

regularly to great acclaim, came up with a hit from time to time, and seemed to

be settling into his establishment-honoured role as a living legend, until 1987.

That year saw him back in a southern jail again - this time for throwing a

drug-fuelled tantrum brandishing a shotgun and nearly getting himself shot to

death in a Keystone Cops chase around state borders.

Released in 1991, a lesser man might have deemed it prudent to retire gracefully

with his multifarious awards on the sideboard. Brown dusted himself off, ordered

a new spangle suit, assembled another band and charged forth once again. It was

never the same as his heyday, but it was never less than an audience with a

formidably dominant personality. Letting off another rifle and another car chase

in 1998 led to a drug rehabilitation programme, and in 2004 he was arrested on

charges of domestic violence against his fourth wife, Tomi Rae Hynie, a former

backup singer. She survives him, as do their son and at least three other

children.

Honours came in the form of a Grammy lifetime achievement award (1992), a

Kennedy Centre Honour (2003) and entry into the UK Music Hall of Fame when he

was in London for an energetic appearance in the BBC Electric Proms at the

Roundhouse last November. With the spirit of one of his 1973 million-sellers,

James Brown kept on Doing It To Death.

James

Brown, G, 26.12.2006,

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/dec/26/

guardianobituaries.usa

MLK's widow

built legacy of her own

Updated 12/26/2006 9:57 PM ET

USA Today

By Larry Copeland

ATLANTA — Coretta Scott King earned worldwide

admiration for her almost-regal bearing and her good works after the

assassination of her husband, civil rights crusader Martin Luther King Jr.

After he was killed in Memphis in 1968,

Coretta Scott King spent much of the next 38 years securing his public legacy.

She campaigned to make her husband's birthday a national holiday and saw those

efforts pay off in 1983 when President Reagan signed a bill doing so.

She founded the King Center almost single-handedly, starting it in the basement

of her home and steering its growth into a national shrine visited by more than

a half-million people annually.

King also was a respected civil rights and human rights figure on her own. She

met during the 1970s with then-President Jimmy Carter and the presidents of the

Urban League and the NAACP to discuss civil rights. She worked in the USA and

abroad to help end apartheid in South Africa and tried to carry on her husband's

philosophy of non-violence through the King Center.

It was her graceful presence and steely determination that were remembered by

many of the thousands who came here from all over the nation during a week of

commemoration after her death Jan. 30 at 78 of complications from a stroke and

ovarian cancer.

King's funeral drew an overflow crowd of mourners and dignitaries including

President Bush and former presidents Clinton, Carter and Bush. President Bush

called her "a beloved, graceful, courageous woman who called America to its

founding ideals and carried on a noble dream."

She was the most tangible connection to Martin Luther King Jr., who is exalted

by many Americans for his unswerving commitment to racial justice and fairness.

She was a classically trained opera singer who married King in 1953 and endured

years of threats and hardship during the civil rights movement.

After her husband was killed in Memphis on April 4, 1968, as he was about to

lead a march by striking city garbage workers, she flew there and vowed to carry

on his work.

After Coretta Scott King's death, thousands stood for hours in cold and rain

outside the Georgia State Capitol where she lay in state, just to get a final

glance. Thousands more lined the route traveled by the horse-drawn carriage that

bore her body. Others waited into the wee hours outside her husband's former

church, Ebenezer Baptist Church, where another viewing was held.

Many of the mourners brought their young children. They said they wanted the

children to know about King's role in helping to banish legalized racial

segregation. Among those in the long lines was Deja Stewart, 9. "To me, she

means a lot," Deja said. "Because of this lady and what she did after he died …

it makes me want to work hard and go to college and get a good education. I

admire her a lot."

In November, King's body was moved from a temporary grave into a crypt that

contains her husband's body. They lie side by side, surrounded by the stillness

of a reflecting pool at the King Center.

MLK's

widow built legacy of her own, UT, 26.12.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-12-26-passages-scott-king_x.htm

Nanny Hunt Can Be

a ‘Slap in the Face’ for

Blacks

December 26, 2006

The New York Times

By JODI KANTOR

Last month, Jennifer Freeman sat in a Chicago

coffee bar, counting her blessings and considering her problem. She had a

husband with an M.B.A. degree, two children and a job offer that would let her

dig out the education degree she had stashed away during years of playdates and

potty training.

But she could not accept the job. After weeks of searching, Ms. Freeman, who is

African-American, still could not find a nanny for her son, 5, and daughter, 3.

Agency after agency told her they had no one to send to her South Side home.

As more blacks move up the economic ladder, one fixture — some would say

necessity — of the upper-middle-class income bracket often eludes them. Like

hailing a cab in Midtown Manhattan, searching for a nanny can be an

exasperating, humiliating exercise for many blacks, the kind of ordeal that

makes them wonder aloud what year it is.

“We’ve attained whatever level society says is successful, we’re included at

work, but when we need the support for our children and we can afford it, why do

we get treated this way?” asked Tanisha Jackson, an African-American mother of

three in a Washington suburb, who searched on and off for five years before

hiring a nanny. “It’s a slap in the face.”

Numerous black parents successfully employ nannies, and many sitters say they

pay no regard to race. But interviews with dozens of nannies and agencies that

employ them in Atlanta, Chicago, New York and Houston turned up many nannies —

often of African-American or Caribbean descent themselves — who avoid working

for families of those backgrounds. Their reasons included accusations of low pay

and extra work, fears that employers would look down at them, and suspicion that

any neighborhood inhabited by blacks had to be unsafe.

The result is that many black parents do not have the same child care options as

their colleagues and neighbors. They must settle for illegal immigrants or

non-English speakers instead of more experienced or credentialed nannies, rely

on day care or scale back their professional aspirations to spend more time at

home.

“Very rarely will an African-American woman work for an African-American boss,”

said Pat Cascio, the owner of Morningside Nannies in Houston and the president

of the International Nanny Association.

Many of the African-American nannies who make up 40 percent of her work force

fear that people of their own color will be “uppity and demanding,” said Ms.

Cascio, who is white. After interviews, she said, those nannies “will call us

and say, ‘Why didn’t you tell me’ ” the family is black?

In several cities, nanny agencies decline to serve certain geographic areas —

not because of redlining, these agencies say, but because the nannies, who

decide which jobs to take, do not want to work there. “I can’t service

everyone,” said Maria Christopoulos-Katris, owner of Nanny Boutique, an agency

that turned down Ms. Freeman’s request, even though it claims to cater to the

city of Chicago. “I don’t discriminate.”

Ms. Freeman finally found a friend, another black mother, to watch her children.

Similarly, Ms. Jackson was told by some of the best-known nanny agencies in

Washington that they did not serve Prince George’s County, Md., a largely black

area bordering the District of Columbia.

“We have problems getting people to certain areas because of logistics,” said

Barbara Kline, the owner of White House Nannies, which Ms. Jackson contacted.

“I’m always worried people will interpret it the wrong way.” She added, “Nannies

like to go where other nannies go or where their previous jobs were.” Ms.

Jackson noted that White House Nannies served other suburbs, and that a bus

stopped just minutes from her house.

Agencies represent only a small slice of nannies; most work through informal

arrangements, further out of reach of civil rights and labor laws. (Because so

many nannies are illegal, no one can say with certainty how many work in this

country, let alone work for black families.)

In visits, telephone calls and e-mail exchanges across the country, nannies of

all colors spoke of parents in sweeping ethnic generalizations: the Jews this,

the Indians that. Viola Waszkiewicz, a white sitter in Chicago, has cared for

black children, but explained that many fellow Eastern European nannies would

not.

“We come here, and we watch TV and the news, and all we see is black people who

got hurt, got murdered,” she said. Most of the nannies she knows “think all

black people are bad,” she said. “They’re afraid to go to black neighborhoods.”

Pamela Potischman, a social worker in Brooklyn who specializes in parent-nanny

relationships, said, “You rely on what’s familiar, so you’re going to rely on

these vast generalizations to be self-protective.” She added, “The nannies talk,

and they say, ‘This is what’s O.K. and what to watch out for.’ ”

This summer, Tomasina and Eric Boone of Brooklyn sought a nanny for their baby

girl because their jobs — she is the advertising beauty director for Essence

magazine, he is a lawyer at Milbank Tweed — require evening hours. After a

Manhattan agency did not return Ms. Boone’s call, they searched on their own,

and sat through one stomach-curdling interview after another.

One sitter, a Caribbean woman living in Bedford-Stuyvesant, asked about the

“colored” people in the Boones’ neighborhood, Clinton Hill. A Russian sitter

said enthusiastically that although she had never cared for a black child, she

could in this case, because little Emerie Boone, now 7 months old, was

light-skinned. All sitters expressed surprise that a black couple could afford a

four-story brownstone.

“There were points where I got so frustrated that I picked up my child and I

said, ‘Tomasina will show you out,’ ” said Mr. Boone, who is African-American

and serves on the board of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People.

The Boones now use day care. It is inconvenient — the center closes at 6, often

forcing Mr. Boone to race to Brooklyn and then back to his Midtown office. But

“there is no way we’re doing the whole nanny thing again,” said Ms. Boone, who

is African-American and Puerto Rican.

Mr. Boone said, “To have someone refer to other black people as ‘colored,’ what

does that teach your child about race?”

Like Ms. Freeman in Chicago and Ms. Jackson in Maryland, the Boones worry that

nanny troubles could limit their professional advancement. In earlier

generations, Ms. Jackson said, “We were the nannies.” Now, blacks “want to have

it all,” working and raising children. “But to have it all you need help,” she

said.

And that means qualified help. “How can you do a background check when someone

doesn’t have a driver’s license?” Ms. Jackson said. “I’m not going to take this

nanny just because she’s the only one I can get.”

In an exception to the usual stroller parade of black sitters with white

children, some white nannies do care for black children — and experience slights

because of it. Margaret Kop, a Polish sitter in Chicago, said that on a recent

playground visit, “one of the other nannies asked me, ‘Where did you find that

monkey?’ ” On the way home, Ms. Kop cried, stung by the insult to the child she

loved.

Some black sitters, both Caribbean and African-American, said they flat out

refused to work for families of those backgrounds, accusing them of demanding

more and paying less.

“It seems like our own color looks down on us and takes advantage of us,” said

Pansy Scott, a Jamaican immigrant in Brooklyn, basing her conclusions on working

for a single black family years ago. Ai-Jen Poo, lead organizer for Domestic

Workers United, a labor group, said, “Domestic employees are at the whim of

their employers,” good or bad. “If they happen to run into an employer who for

whatever reason is not respecting their rights,” she said, they may draw wildly

broad conclusions.

The problem may be as much about class as race, said Kimberly McClain DaCosta, a

Harvard sociologist who is researching how blacks care for family members. For

nannies, working for an employer of the same background or skin color

“highlights their lower economic status,” she said, but “the fact that their

employers are black just makes that more intense.”

Many black families say they seek only a sitter who is reliable and loving. But

some do have race-based preferences themselves. African-American professionals,

who constantly battle the stereotype that blacks do not speak proper English,

sometimes hesitate to hire Caribbean nannies who speak with lilting accents or

island patois, said Cameron L. Macdonald, an assistant professor of sociology at

the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

These parents want their children “socialized into what it’s like to be black in

a racist society, but they also want their children to be socialized into being

middle class. That’s hard for one person to do,” said Ms. Macdonald, who is

white.

Ms. DaCosta is an African-American parent herself. She and her husband, who is

Caribbean, have successfully employed several nannies for their three children.

Still, the hiring process has been tricky. They preferred a black sitter, who

would instantly understand matters like how to do their daughter’s hair. At one

point, Ms. DaCosta scouted playgrounds, so she could spy on nannies’ skin color

as well as behavior; another time, she placed a race-neutral ad, and hid by the

window as the prospective nannies drove up, sighing with relief when a black one

appeared.

Ms. DaCosta and her husband now use au pairs, checking the photos on their

applications and announcing their own race at the start of the phone interview.

“We don’t want any surprises,” she said.

Nanny

Hunt Can Be a ‘Slap in the Face’ for Blacks, NYT, 26.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/26/us/26nannies.html

Black History Trove,

a Life’s Work,

Seeks Museum

December 14, 2006

The New York Times

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER

LOS ANGELES, Dec. 13 — Behind the dusty stools and the old

towels, under the broken telephones and the picture frames, amid the spider

webs, sits one of the country’s most important collections of artifacts devoted

to the history of African-Americans.

Painstakingly collected over a lifetime by Mayme Agnew Clayton — a retired

university librarian who died in October at 83 and whose interest in

African-American history consumed her for most of her adult life — the massive

collection of books, films, documents and other precious pieces of America’s

past has remained essentially hidden for decades, most of it piled from floor to

ceiling in a ramshackle garage behind Ms. Clayton’s home in the West Adams

district of Los Angeles.

Only now is her son Avery Clayton close to forming a museum and research

institute that would bring her collection out of the garage and into public

view. Just days before Ms. Clayton died, he rented a former courthouse in nearby

Culver City for $1 a year to become the treasures’ home, leaving him to scrape

together $565,000 to move the thousands of items and put them on display for the

first year.

“There is no doubt that this is one of the most important collections in the

United States for African-American materials,” said Sara S. Hodson, curator of

literary manuscripts for the Huntington Library in San Marino, one of the

country’s largest collections of rare books and manuscripts. “It is a tremendous

resource for all Americans, but especially African-Americans, whose history has

largely been neglected.”

There are first editions by Langston Hughes and nearly every other writer from

the Harlem Renaissance, many of them signed; a rare biography of the architect

Paul R. Williams; and the oeuvre of the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

There is an edition of “The Negro’s Complaint,” a poem complete with

hand-painted illustrations; books by and about every notable American of African

descent from George Washington Carver to Bill Cosby; and thousands more items

concerning those whose names were lost or never known.

The roughly 30,000 rare and out-of-print books written by and about blacks in

Ms. Clayton’s collection have never been fully archived.

There is also what Mr. Clayton calls the world’s largest collection of 16-mm

films made by blacks; 75,000 photographs; 9,500 sound recordings; and tens of

thousands of documents, manuscripts and correspondence: a treasure trove that

Ms. Clayton assembled piece by piece, on her modest salary, scouring used

bookstores, garage sales, antique shops and pretty much any place where she

could find books and memorabilia related to the African-American experience.

The premier collection devoted to black literature and artifacts is the

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Other major

collections include the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American

History at the Chicago Public Library, and those of Howard University, Temple

University and the University of Arkansas.

Ms. Clayton’s collection is distinguished by its breadth and depth of materials,

scholars say, including the films, the handwritten slave documents and the

staggering assortment of ephemera, and is unmatched on the West Coast. “A

collection like this is, in my mind, priceless,” said Philip J. Merrill, an

expert on African-American memorabilia.

Mr. Clayton recalled his mother’s longing — and inability — to find a home for

her collection, where it could be used by everyone from esteemed scholars to

black teenagers who have yet to hear of W. E. B. Du Bois. “Culture is the

measure of a civilization,” said Mr. Clayton, who left his job as an art teacher

to shepherd his mother’s collection. “Without evidence of a culture, there is no

proof that a people exists.”

For now, the future Mayme E. Clayton Library and Cultural Center has a jail cell

(which may one day store sensitive items), three courtrooms (one with leather

seats will be a theater) and a large portrait that Mr. Clayton painted of his

mother.

But if all goes well, in 2008 it will become a research center, perhaps even a

repository for other large collections of African-American history that, like

his mother’s, are “sitting in boxes in the basements of homes and church

libraries, waiting for a flood,” Mr. Clayton said.

The dispersion of important African-American cultural materials has long vexed

researchers. “The older materials have always been collected out of a labor of

love by someone who had the foresight to realize that researchers would find it

valuable,” said Patricia A. Turner, a professor of African-American studies at

the University of California, Davis. Putting such works together “will be very

important for the scholarly community.”

Ms. Clayton’s interest in literature and black history was sparked during her

childhood in Van Buren, Ark. Her father, a black merchant, wanted his children

“exposed to black people of accomplishment,” Mr. Clayton said. Her father once

took the family to visit Mary McLeod Bethune in Little Rock.

“I always had a desire to want to know more about my people,” Ms. Clayton said

in a 2005 interview with the HistoryMakers, a video oral-history archive. “I

would hear about another person, so I would go and try to find some books about

that one. And it just snowballed.”

Ms. Clayton came to New York in her 20s, met Andrew Lee Clayton, whom she

married in 1946, and soon moved to California to a tiny bungalow in historic

West Adams where she started a family.

Her collecting grew from her work as a librarian, first at the University of

Southern California and later at the University of California, Los Angeles,

where she began to build an African-American collection.

In 1969 she helped establish the university’s African-American Studies Center

Library, and began to buy out-of-print works by authors from the Harlem

Renaissance.

Around that time, Ms. Clayton invested in a bookstore. When the principal owner

squandered their profits on the horses, Mr. Clayton said, his mother agreed to

take her partner’s collection of black-oriented books rather than take him to

court.

Her business acumen became well known in the field. “I distinctly remember

trading four items I had, which included a signed poem by Langston Hughes, for

one book,” said Randall K. Burkett, the curator of African-American collections

at Emory University. “Let’s just say she did very well.”

Ms. Clayton, an avid golfer, traveled for her sport, trolling for rare finds

wherever she went. The centerpiece of the collection that grew this way is a

signed copy of Phillis Wheatley’s “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and

Moral,” from 1773. First published by an American of African descent, the book

was acquired for $600 from a New York dealer in 1973. In 2002 it was appraised

at $30,000.

The books and others items Ms. Clayton amassed cost her hundreds of thousands of

dollars over the years, her son said, money she got through scrimping, selling

off books occasionally and living modestly.

Mr. Clayton, one of Ms. Clayton’s three sons, dreams of housing his mother’s

collection in a 40,000-square-foot hilltop cultural center with an atrium

garden, performance space and archived research center. “She always wanted

something grand,” he said. He estimates it would cost $7 million to operate the

center for three years. So far he has raised $15,000 and he said he was working

with his congresswoman for a $150,000 appropriation.

For now he just wants the collection out of her garage — the films and some

other items are in storage — and into the former courthouse, where the world can

see it.

“One of the things that culture does is that it works like a family,” Mr.

Clayton said. “If you know you come from a good family, it enables you to go out

into the world, no matter what happens to you, and do O.K. It is the same thing

with culture: If you know you come from a great people, it gives you that same

feeling.”

Black History

Trove, a Life’s Work, Seeks Museum, NYT, 14.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/14/arts/14clay.html

Political Drama

Re-enacts Moments

in a

Death Chamber

December 14, 2006

The New York Times

By JESSE McKINLEY

BERKELEY, Calif., Dec. 13 — As drama, what

happened on stage at the Black Repertory Theater of Berkeley early Wednesday

morning was not classic theatrical fare. The actors were mostly motionless, the

play had only one line, and everyone in the audience knew how the story was

going to end.

But creating a compelling narrative may not have been the authors’ point. The

play was a re-enactment of the execution of the convicted killer Stanley Tookie

Williams, staged on the first anniversary of his death by lethal injection at

San Quentin State Prison.

The performance was written and produced by Barbara Becnel and Shirley Neal, two

friends of Mr. Williams and death penalty opponents, who were unapologetic about

their play’s being agitprop.

“This is political theater in the extreme,” Ms. Becnel told a crowd of about 150

people who gathered to watch the performance. “But it’s political theater in the

extreme because we need it.”

The execution of Mr. Williams, 51, a founder of the Crips gang who was convicted

of murdering four people in 1979, has continued to be a rallying point for death

penalty opponents as well as a source of contention about the methods of lethal

injection.

In September, a representative of the state attorney general’s office

acknowledged that prison guards and nurses had botched Mr. Williams’s lethal

injection, failing to hook up a backup intravenous line to his arm. Ms. Becnel

said Mr. Williams was in agony during his execution, which took 35 minutes to

complete.

“I was there, I saw what they did,” Ms. Becnel said. “And I can tell you it was

a 35-minute torture-murder.”

State officials deny that Mr. Williams suffered unnecessarily. “The execution

went exactly as the protocol is designed to carry it out,” said Nathan Barankin,

a spokesman for Attorney General Bill Lockyer. “The lack of the extra IV line

was definitely a mistake, but it didn’t affect the execution.”

Michael Rushford, president of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, an

advocate for victims’ rights and law enforcement, said he believed Mr. Williams

was a bad role model for a play.

“I think it hurts the anti-death-penalty movement to hold up as dastardly a

criminal as Tookie,” Mr. Rushford said, citing Mr. Williams’s work with the

Crips, a violent gang based in Los Angeles.

Mr. Rushford added that Wednesday morning’s performance was simply “preaching to

the choir” of Mr. Williams’s supporters, many of whom rallied in front of San

Quentin the night of his execution.

“I don’t expect an accurate portrayal of what happened,” he said. “But when

you’ve made such a big deal of it, you can’t just let it drop after a year.”

Mr. Williams’s experiences in the death chamber were part of a Federal District

Court hearing in September — stemming from a lawsuit by Michael Morales, a

condemned rapist and killer — that may affect death penalty methodology in

California. The judge overseeing the hearings, Jeremy Fogel, effectively halted

executions in California until he could hear arguments on whether methods of

lethal injection caused undue pain. Judge Fogel is expected to issue a ruling

soon.

For supporters of Mr. Williams, his execution, which drew international press

attention and a cadre of celebrity protesters, was unjust, in part because of

his post-incarceration work speaking about the dangers of gangs through a series

of children’s books, lectures and memoirs, many of which were written with Ms.

Becnel. Mr. Williams also claimed to be innocent.

On Wednesday, the theatrical re-enactment began at 12:01 a.m., the time Mr.

Williams entered the death chamber. It was performed by six actors, including

Darby Tillis, 64, an exonerated death row inmate from Chicago who played Mr.

Williams and said he had little trouble connecting with the role.

“When you’re on death row, you always have an imaginary scene that you live out

many times: how you would feel if you went down for an execution,” Mr. Tillis

said.

With a simple set — folding chairs, a gurney and a platform — the play’s action

was minimal: three witnesses stood, a guard strapped Mr. Tillis to a gurney, a

nurse fumbled with an IV. Only once did anyone speak, when Mr. Tillis asked the

actor playing the frustrated nurse whether she knew what she was doing. The

entire performance took about 12 minutes — about a third of the actual execution

time.

And while the audience was silent throughout, some said the experience had left

them shaken. Kirya Traber, 22, who wore a Save Tookie T-shirt, said she had been

outside San Quentin the year before, but felt a lot closer to the drama on

Wednesday.

“Here tonight,” Ms. Traber said, “was a lot more solemn.”

Political Drama Re-enacts Moments in a Death Chamber, NYT, 14.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/14/us/14tookie.html

Editorial

An Assault

on Local School Control

December 4, 2006

The New York Times

More than 50 years after the Supreme Court decided Brown v.

Board of Education, the nation still has not abolished de facto segregation in

public schools. But thanks to good will and enormous effort, some communities

have made progress. Today the Supreme Court hears arguments in a pair of cases

that could undo much of that work.

Conservative activists are seeking to halt the completely voluntary, and

laudable, efforts by Seattle and Louisville, Ky., to promote racially integrated

education. Both cities have school assignment plans known as managed or open

choice. Children are assigned to schools based on a variety of factors, one of

which is the applicant’s race.

The plan that Jefferson County adopted for Louisville has a goal of having black

enrollment in every school be no less than 15 percent and no more than 50

percent. Seattle assigns students to its 10 high schools based on a number of

factors, including an “integration tiebreaker.” This tiebreaker, which is

applied to students of all races, requires that an applicant’s race be taken

into account when a school departs by more than 15 percent from the district’s

overall racial breakdown.

Parents in both districts sued, alleging that the consideration of race is

unconstitutional. In each case, the court of appeals upheld the assignment

plans. In the Seattle case, Judge Alex Kozinski, a Reagan appointee who is

highly respected by legal conservatives, wrote that because the district’s plan

does not advantage or disadvantage any particular racial group — its

pro-integration formula applies equally to all — it “carries none of the baggage

the Supreme Court has found objectionable” in other cases involving race-based

actions.

The Louisville and Seattle plans are precisely the kind of benign race-based

policies that the court has long held to be constitutional. Promoting diversity

in education is a compelling state interest under the equal protection clause,

and these districts are using carefully considered, narrowly tailored plans to

make their schools more diverse.

It is startling to see the Justice Department, which was such a strong advocate

for integration in the civil rights era, urging the court to strike down the

plans. Its position is at odds with so much the Bush administration claims to

believe. The federal government is asking federal courts to use the Constitution

to overturn educational decisions made by localities. Conservative activists

should be crying “judicial activism,” but they do not seem to mind this activism

with an anti-integration agenda.

If these plans are struck down, many other cities’ plans will most likely also

have to be dismantled. In Brown, a unanimous court declared education critical

for a child to “succeed in life” and held that equal protection does not permit

it to be provided on a segregated basis. It would be tragic if the court changed

directions now and began using equal protection to re-segregate the schools.

An Assault on

Local School Control, NYT, 4.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/04/opinion/04mon1.html

Sharpton and Jesse Jackson

Lead Angry Group

to Site of Deadly Police Shooting

November 30, 2006

The New York Times

By SEWELL CHAN and DARYL KHAN

The Revs. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton led

relatives and community members on an angry and emotional visit yesterday

morning to the Queens street where Sean Bell, an unarmed 23-year-old black man,

was shot to death in a hail of police bullets early Saturday morning.

As the two civil rights leaders led their group, police officers continued

searching the site for evidence yesterday, and investigators were seeking

additional witnesses.

The police were trying to locate a man who may have been in Mr. Bell’s car on

Saturday morning and another who witnesses say was at the heart of arguments

outside Club Kalua, a cabaret, with groups that included Mr. Bell. That man was

last seen dressed in black and standing in front of a sport utility vehicle with

silver wheels in the moments before the shooting. It is unclear what role, if

any, he played, the police said.

The police described the man who may have been in Mr. Bell’s car as being last

seen wearing a beige jacket and running away from the shooting onto 95th Avenue,

the police said.

As investigators working on the case seek the two men, the police are asking

everyone arrested in the city whether they have any information about the case.

The case has attracted national attention, a fact underscored by the arrival of

Mr. Jackson and by a call from Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg to Bruce S. Gordon,

president and chief executive of the N.A.A.C.P., which wants the Justice

Department to review whether the shooting violated federal civil rights laws.

Mr. Jackson echoed that sentiment yesterday.

Mr. Gordon said the mayor, who has made fighting poverty a priority of his

second term, had expressed interest in improving education and job opportunities

for young black men. “I at least find his approach to be refreshing,” Mr. Gordon

said, “but in no way am I comforted, because this incident just points out the

disparities and abuses in the system that have to be changed.”

On Monday the mayor called the shooting “excessive,” a characterization that

Gov. George E. Pataki agreed with.

“Obviously, 50 bullets fired into or at an unarmed individual in New York is

excessive force,” Mr. Pataki said yesterday in a news conference broadcast by

satellite from Kuwait, “but the appropriate response to that is something that I

think the investigation of the mayor and the police commissioner will reveal.”

Mr. Sharpton hinted yesterday that he might call for a shopping boycott to

protest the shooting.

Shortly before 9 a.m., Mr. Sharpton and Mr. Jackson led elected officials and

clergy members to the spot in Jamaica, Queens, where five officers fired 50

shots at Mr. Bell’s car during a confrontation in which he drove into one of the

officers and an unmarked police van. Two friends of Mr. Bell, Trent Benefield,

23, and Joseph Guzman, 31, were also in the car and were seriously wounded.

On Liverpool Street, at an impromptu sidewalk memorial of white carnations, red

roses, candles and photographs taped to a brick wall, Mr. Bell’s aunt, the Rev.

Diane Shepherd-Oliver, a minister at the New Life Temple of Praise in Syracuse,

called for God’s help. “Pray for the policemen and the other individuals who are

injured,” she said.

Mr. Bell’s parents, William and Valerie, and his fiancée, Nicole Paultre, whom

he was to wed the day he was killed, were among those in the group.

“We appeal to people: Don’t do anything disruptive or in any way contrary to the

memory of Sean Bell,” Mr. Sharpton said. “We do not want the world to see him as

anything other than what he was. He was not violent. He was not a thug. He was

not in the street. Don’t use your anger to distort who he was.”

Mr. Jackson said of the shooting: “This is a symbol, not an aberration. Our

criminal justice system has broken down for black Americans and the young black

males.”

Mr. Guzman’s sister, Yolanda, who has been at his bedside at Mary Immaculate

Hospital, said of her brother, whom she helped raise: “He’s critical. He cannot

talk. He has 19 holes in him.”

Mr. Guzman’s companion, Ebony Browning, squeezed the hand of their son, Juan, 6,

and lighted a candle and taped up a photo of Mr. Guzman. “Pray for my child and

pray for my husband, too,” she said.

Al Baker and Michael Cooper contributed reporting.

Sharpton and Jesse Jackson Lead Angry Group to Site of Deadly Police Shooting,

NYT, 30.11.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/30/nyregion/30shoot.html

Lawyers Debate

Why Blacks Lag at Major

Firms

November 29, 2006

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

Thanks to vigorous recruiting and pressure

from corporate clients, black lawyers are well represented now among new

associates at the nation’s most prestigious law firms. But they remain far less

likely to stay at the firms or to make partner than their white counterparts.

A recent study says grades help explain the gap. To ensure diversity among new

associates, the study found, elite law firms hire minority lawyers with, on

average, much lower grades than white ones. That may, the study says, set them

up to fail.

The study, which was prepared by Richard H. Sander, a law professor at the

University of California, Los Angeles, and was published in The North Carolina

Law Review in July, has given rise to fierce and growing criticism in law review

articles and in the legal press. In an opinion article in The National Law

Journal this month, for instance, R. Bruce McClean, the chairman of Akin Gump

Strauss Hauer & Feld, a major law firm, took issue with the study’s “sweeping

conclusions” but not its “detailed data analysis.”

James E. Coleman Jr., the first black lawyer to make partner at Wilmer Cutler &

Pickering, a prestigious Washington law firm now known as WilmerHale, said

Professor Sander was overemphasizing grades at the expense of other qualities

like writing skills, temperament and the ability to analyze complex problems.

“I don’t think you can do what he is trying to do, which is to use purely

objective data to explain what is happening in law firms,” said Professor

Coleman, who now teaches law at Duke and is a co-author of a response to

Professor Sander called “Is It Really All About the Grades?”

Achieving racial diversity at all levels is an urgent issue, law firms say, but

they acknowledge that gains among new associates disappear by the time new

partners are elected. “We’ve seen stagnation and even decline when it comes to

race,” said Meredith Moore, the director of the New York City Bar Association’s

diversity office.

The new study proposes an explanation. It found that the pool of black lawyers

with excellent law-school grades is so small that firms must relax their

standards if they are to have new associates who resemble the pool of new

lawyers.

Professor Sander found that very few blacks graduated from top-30 law schools

with high grades.

Yet grades, according to many hiring partners and law students, are a

significant criterion in hiring decisions, rivaled only by the prestige of the

law school in question. For instance, Professor Sander found, “white law school

graduates with G.P.A.’s of 3.5 or higher are nearly 20 times as likely to be

working for a large law firm as are white graduates with G.P.A.’s of 3.0 or

lower.”

The story for black students appears to be different. Black students, who make

up 1 to 2 percent of students with high grades (meaning a grade point average in

the top half of the class) make up 8 percent of corporate law firm hires,

Professor Sander found. “Blacks are far more likely to be working at large firms

than are other new lawyers with similar credentials,” he said.

But black lawyers, the study found, are about one-fourth as likely to make

partner as white lawyers from the same entering class of associates.

Professor Coleman attributed that largely to law firms’ failure to provide

minority associates with mentoring, encouragement and good assignments. “It’s

such a high-pressure place that places so much emphasis on getting it right that

a young associate easily loses confidence,” he said. “But to succeed you have to

take risks.”

No one disputes that firms are failing to retain and promote most of the

minority lawyers they hired, at salaries that can start at $135,000.

“Black and Hispanic attrition at corporate firms is devastatingly high,”

Professor Sander wrote, “with blacks from their first year onwards leaving firms

at two to three times the rate of whites. By the time partnership decisions roll

around, black and Hispanic pools at corporate firms are tiny.”

Less prestigious firms are much less likely to hire minority lawyers with

substantially lower grades than white lawyers, Professor Sander said in an

interview.

“Black associates report experiences at small firms — in mentoring, job

responsibility and contact with partners — that are generally indistinguishable

from the experiences reported by white associates,” Professor Sander said. Those

experiences suggest that minority lawyers at small firms have a good shot at

partnership, but Professor Sander said he did not have direct evidence on that

point.

Critics generally concede the raw numbers. But they offer different reasons for

the gap between hiring and promotion. Some point to old-fashioned racism. Others

say that firms act institutionally in hiring but leave work assignments to

individual partners. Those partners often provide poor training, rote

assignments and little mentoring to minority lawyers.

That should be unsurprising given the credentials gap, said Roger Clegg,

president of the Center for Equal Opportunity, which opposes hiring preferences

based on race.

“If everyone in the law firms knows you’re hiring according to a double

standard, you actually may end up compromising the confidence that partners and

others have in the ability of people hired on the basis of preference,” Mr.

Clegg added. “It actually reinforces stereotypes.”

The experience of white female associates provides a series of contrasts. Women

at large firms have slightly better grades than men, yet they are also

underrepresented in classes of new partners. But women do not report the absence

of mentoring and choice assignments that minority associates do.

“Strikingly, women’s self-reported work experiences — in terms of mentoring,

level of responsibility and access to partners — are positive and

indistinguishable from the self-reports of white men,” Professor Sander said.

“Consistent with this picture, white women’s attrition rates as entering and

midlevel associates are nearly as low as those of white men.”

Associates typically work for about eight years before being considered for

partnership. “As women of all races approach the seventh year of their tenure,

and contemplate the compatibility of big-firm partnership with their family and

quality-of-life goals,” Professor Sander said, “many women pull out of the

running for partners and seek out less demanding jobs.”

Though many supporters of affirmative action question Professor Sander’s

conclusions, most academic experts say his empirical work is sound.

“He makes a good case,” said Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt, an authority on the

economic analysis of legal problems at the Indiana University School of Law.

“What the data tells him is that there’s a mismatch going on and it’s hurting

black students.”

In their response to the Sander study, Professor Coleman and Mitu Gulati,

another law professor at Duke, wrote that the Sander paper would aggravate the

problem it described.

“The harm of the Sander article,” the two professors wrote, “is that it will

contribute to the stereotyping that already undermines the success of black

associates in elite corporate law firms.”

Stephen F. Hanlon, a partner with Holland & Knight, a national law firm, said

the Sander study overlooked a positive reason for high attrition rates among

minority lawyers. Female and minority lawyers, he said, are often hired away

from law firms by corporate law departments, and that will have an impact over

time.

“We have trained a very bright generation of women and minority lawyers who have

gone to our corporate clients and who now decide whether to hire us,” Mr. Hanlon

said.

Supporters of affirmative action acknowledge that trend, and add that high rates

of minority attrition should be unsurprising given the grinding, mercenary

culture of most law firms.

“Minorities, when they look at management structures and see that so few make

it, they probably give up,” said Veta T. Richardson, the executive director of

the Minority Corporate Counsel Association.

Even Professor Sander’s critics say he has started an important discussion.

“We have done our share of stone throwing,” Professor Coleman and Professor

Gulati wrote in their response, “but that should not take away from the fact

that Professor Sander has identified a real problem that needs serious study,

and that his study has added considerably to the limited body of available,

public research, even though his conclusions are, at best, premature.”

Lawyers Debate Why Blacks Lag at Major Firms, NYT, 29.11.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/29/us/29diverse.html

Bebe Moore Campbell,

Novelist of Black

Lives,

Dies at 56

November 28, 2006

The New York Times

By MARGALIT FOX

Bebe Moore Campbell, a best-selling novelist

known for her empathetic treatment of the difficult, intertwined and

occasionally surprising relationship between the races, died yesterday at her

home in Los Angeles. She was 56.

The cause was complications of brain cancer, said Linda Wharton-Boyd, a longtime

friend.

Along with writers like Terry McMillan, Ms. Campbell was part of the first wave

of black novelists who made the lives of upwardly mobile black people a routine

subject for popular fiction. Straddling the divide between literary and

mass-market novels, Ms. Campbell’s work explored not only the turbulent dance

between blacks and whites but also the equally fraught relationship between men

and women.

Throughout her work, Ms. Campbell sought to counter prevailing stereotypes of

black people as socially and economically marginal. Though critics occasionally

faulted her characters as two-dimensional, her novels were known for their

crossover appeal, read by blacks and whites alike.

Often called on by the news media to discuss race relations, Ms. Campbell was

for years a familiar presence on television and radio. With the publication of

her most recent novel, “72 Hour Hold” (Knopf, 2005), she also became a visible

spokeswoman on mental-health issues. The novel, about bipolar disorder, was

inspired by the experience of a family member, Ms. Campbell said.

Originally a schoolteacher and later a journalist, Ms. Campbell made her mark as

a writer of fiction with her first novel, “Your Blues Ain’t Like Mine” (Putnam),

published in 1992. Rooted in the story of Emmett Till, the book tells of a black

Chicago youth killed by a white man in Mississippi in 1955. After the murderer

is acquitted at trial, the narrative follows his increasing dissolution.

“I wanted to give racism a face,” Ms. Campbell said in an interview with The New

York Times Book Review in 1992. “African-Americans know about racism, but I

don’t think we really know the causes. I decided it’s first of all a family

problem.”

Reviewing the novel in The Book Review, Clyde Edgerton wrote: “By showing lives

lived, and not explaining ideas, Ms. Campbell does what good storytellers do —

she puts in by leaving out.”

Ms. Campbell’s other novels, all published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, are “Brothers

and Sisters” (1994), written in the wake of the Los Angeles riots of 1992;

“Singing in the Comeback Choir” (1998), about a black television producer

feeling cut off from her roots; and “What You Owe Me” (2001), about the

friendship between two women, one African-American, the other a Jewish Holocaust

survivor, in the 1940’s.

Elizabeth Bebe Moore was born in Philadelphia on Feb. 18, 1950, to parents who

divorced when she was very young. Bebe spent each school year in Philadelphia

with her mother, grandmother and aunt — strong, upright women she collectively

called “the Bosoms” — who set her on a course of study, discipline and staunch

middle-class respectability.

She spent summers in North Carolina with her father, who had been paralyzed in

an automobile accident. There, she was enveloped in a heady world of beer,

laughter and cigar smoke. She documented her contrasting lives in her memoir,

“Sweet Summer: Growing Up With and Without My Dad” (Putnam, 1989).

After earning a bachelor’s degree in elementary education from the University of

Pittsburgh in 1971, Ms. Campbell taught school in Atlanta for several years

before embarking on a career as a freelance journalist. Her first book was a

work of nonfiction, “Successful Women, Angry Men: Backlash in the Two-Career

Marriage” (Random House, 1986).

She also wrote two picture books for children, “Sometimes My Mommy Gets Angry”

(Putnam, 2003; illustrated by E. B. Lewis); and “Stompin’ at the Savoy”

(Philomel, 2006; illustrated by Richard Yarde).

Ms. Campbell’s first marriage, to Tiko Campbell, ended in divorce. She is

survived by her husband, Ellis Gordon Jr., whom she married in 1984; her mother,

Doris Moore of Los Angeles; a daughter from her first marriage, Maia Campbell of

Los Angeles; a stepson, Ellis Gordon III of Mitchellville, Md.; and two

grandchildren.

Despite the subject matter of her books, Ms. Campbell expressed hope about the

future of American race relations. In an interview with The New York Times in

1995, she described her motivation for writing “Brothers and Sisters,” the story

of the friendship between a black banker and her white colleague.

“It was my attempt to bridge a racial gap,” Ms. Campbell said. “That’s the story

that never gets told: how many of us really like each other, respect each

other.”

Bebe

Moore Campbell, Novelist of Black Lives, Dies at 56, NYT, 28.11.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/28/books/28campbell.html

In Cincinnati,

Life Breathes Anew

in

Riot-Scarred Area

November 25, 2006

The New York Times

By CHRISTOPHER MAAG

CINCINNATI — A few years ago, Jim Moll, a real

estate agent, turned to his friend Bill Baum, a developer, and asked whether

anyone would ever sell condominiums on Vine Street, the epicenter of race riots

here in 2001.

“Not in our lifetimes,” Mr. Moll recalls Mr. Baum replying.

One recent afternoon, Mr. Baum, 57, stood on the battered pine floorboards of a

130-year-old building on Vine Street as a workman mixed cement in a wheelbarrow.

Mr. Baum’s company, Urban Sites, is transforming this vacant brick shell into

six condominiums, which he plans to sell by next summer.

“To hear the jackhammers and the booms and the nail guns,” Mr. Baum said, “it’s

music to me.”

Vine Street runs through the heart of Over-the-Rhine, a neighborhood of narrow

streets and ornate brick buildings built by German immigrants from 1865 to the

1880s. After decades of decay in the area, gentrification is spreading north

from downtown and south down the steep hillside of Mount Auburn. New

condominiums, art galleries, theaters and cafes are bringing people and

investment.

But poverty remains, as do drugs, violent crime and the stigma of the three days

of riots in 2001. The riots effectively killed an earlier Over-the-Rhine

renaissance, in the late 1990s.

The magic of Over-the-Rhine is in its compact brick buildings. Mostly two- to

four-story walkups, few are significant individually. But together they create a

historic district with a scale and grace reminiscent of Greenwich Village in New

York. In May the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed the entire

362-acre neighborhood as one of the country’s 11 Most Endangered Historic

Places.

As Over-the-Rhine’s white families left for the suburbs after World War II, its

buildings attracted black families displaced when Interstate 75 tore through the

nearby West End neighborhood, said Vice Mayor Jim Tarbell, who moved to

Over-the-Rhine in 1971. It gradually became a slum in what the Census Bureau has

found is the sixth most segregated city in the nation.

By 1990 the neighborhood’s median family income was $4,999, census figures show.

It was the most dangerous part of the city, according to Police Department

records, with almost 22,000 calls for emergency service, 8 murders and 306

robberies in 2001.

During the first renaissance, a generation of young hipsters discovered

Over-the-Rhine, drawn by sturdy, funky and affordable buildings just a

five-minute walk from downtown. The first nightclubs moved to the area in the

1980s, followed by art galleries and specialty shops. St. Theresa Textile Trove

opened in 1994 and attracted art quilters from across the country, said Becky

Hancock, its owner. A few doors down stood the Suzanna Terrill Gallery.

At the height of the boom, Mr. Baum said, young downtown office and restaurant

workers placed down payments on future apartments that still had garbage piled

on the floor and pigeons nesting in the walls.

“There was this palpable feeling that things were really taking off,” said Ran

Mullins, who moved to the neighborhood in 1999 and now owns Metaphor Studios, an

advertising agency in Over-the-Rhine.

But early in the morning of April 7, 2001, Stephen Roach, a white police

officer, shot and killed Timothy Thomas, an unarmed African-American, after a

foot chase. A protest march two days later devolved into riots. Many

Over-the-Rhine businesses were looted.

After the riots, redevelopment projects fizzled. Most of the nightclubs closed.

Demand for apartments dwindled, Mr. Baum said. Art galleries, including Suzanna

Terrill’s, closed, and St. Teresa Textile Trove moved to another neighborhood

because customers refused to drive into Over-the-Rhine.

“The riots set this neighborhood back a decade,” Mr. Mullins said.

Paradoxically, the riots’ reverberations may actually speed Over-the-Rhine’s

recovery. Afterward, thousands of renters receiving federal rent subsidies left

the neighborhood.

“A huge number of people just vamoosed,” said Marge Hammelrath, director of the

Over-the-Rhine Foundation.

Their exodus left 500 of the neighborhood’s 1,200 buildings vacant, according to

the Trust for Historic Preservation. Property values dropped, making it easier

for developers to buy into the neighborhood.

But unlike the last boom, where small developers rehabilitated buildings one at

a time, Over-the-Rhine’s current wave of gentrification is driven by

Cincinnati’s corporate and philanthropic elite, whose strategy is to buy entire

blocks. The largest player is the Cincinnati Center City Development

Corporation, known locally as 3CDC, which was created in 2003 with $80 million

raised by the city’s corporate leaders.

In the last 18 months, 3CDC invested $27 million in Over-the-Rhine, buying 100

buildings and 100 vacant lots, said the organization’s president, Stephen

Leeper. It completed 28 new condominiums on Vine last year and is building 68

more.

Next came the Art Academy of Cincinnati, which spent $13 million to move from

its hilltop campus into two adjacent warehouses in Over-the-Rhine last summer.

Now the academy’s sign, which is four stories tall and reads “ART” in red neon

letters, casts its light into new condominiums. The academy also became an

anchor for smaller arts groups, like Know Theater of Cincinnati.

The neighborhood’s rapid growth makes some people worry that low-income families

will be pushed out.

“Obviously the architecture is beautiful,” said Bonnie Neumeier, a community

activist. “But we feel that the faces of our people are more important than the

facades of the buildings.”

This time, the biggest threat to revitalization may come less from crime or

racial tension than from Over-the-Rhine’s buildings themselves. Many sat vacant

for so long that they are on the verge of collapse, Mr. Tarbell said, and some

that were used as crack dens were bulldozed.

“This is a race,” said Bill Donabedian, a director at 3CDC. “If we don’t move

quickly, we will lose these buildings forever.”

In

Cincinnati, Life Breathes Anew in Riot-Scarred Area, NYT, 25.11.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/25/us/25cincy.html

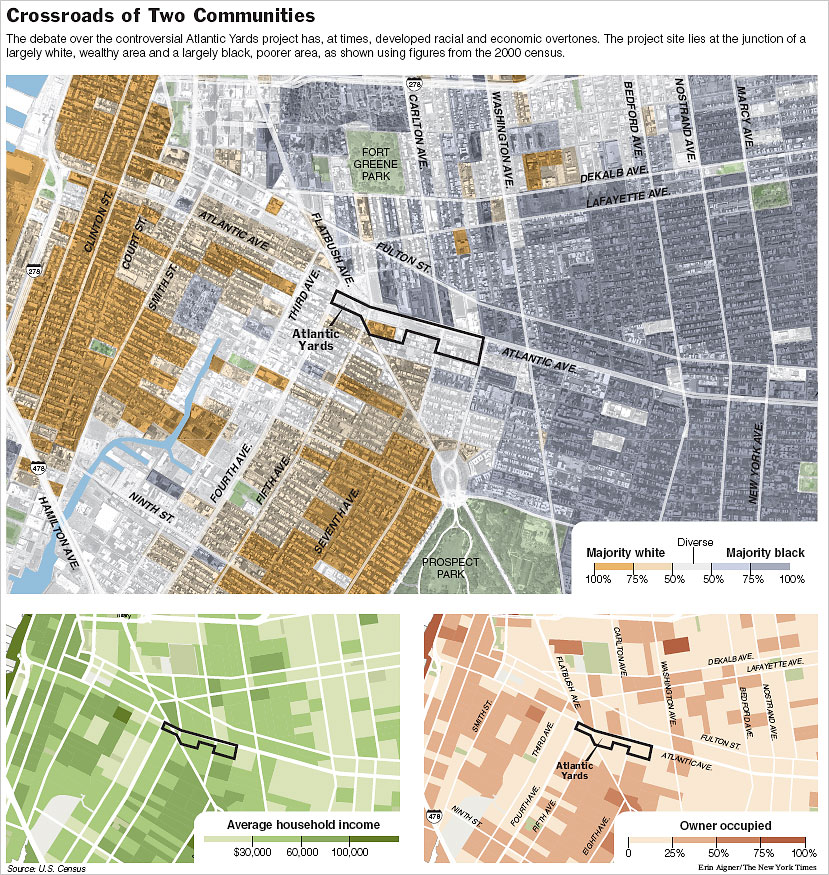

Perspectives on the Atlantic Yards

Development

Through the Prism of Race

NYT

12.11.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/12/nyregion/12yards.html

Perspectives

on the Atlantic Yards Development

Through the Prism of Race

November 12, 2006

The New York Times

By NICHOLAS CONFESSORE

It was the first of three public hearings on the $4.2

billion Atlantic Yards development, and Umar Jordan, a 51-year-old resident of

Bushwick, Brooklyn, strode to the front of the auditorium and offered a vigorous

defense of the proposal. “I’m here to speak for the underprivileged, the people

that don’t get the opportunity to work, the brothers that just came over out of

prison,” he said.

Those who opposed the plan, he said, were not true Brooklynites. Their concerns

about traffic and noise were trivial. And stopping the project would force

“young black men” into a life of crime. “I suggest you go back up to

Pleasantville,” he concluded.

It was not the first time race has bubbled up to the roiling, overheated surface

of the Atlantic Yards debate, where charges of dishonesty and bad faith fly with

abandon. Indeed, take any major debate about urban development in Brooklyn in

recent years, and sooner or later, the issue of race has moved front and center

— usually linked to the question of who wins and who loses.

Some of the racial rhetoric in this fight has inverted the classic development

squabble in which affluent, usually white New Yorkers tolerate ambitious

development, while working-class people, often minorities in struggling

neighborhoods, fear they will not enjoy its fruits.

Like Mr. Jordan, many of the most fervent supporters of Atlantic Yards present

the project as a beacon of hope for black residents living near the proposed

8.7-million-square-foot project.

Critics of the project — black and white — see merely the same old development

debate, punctuated by what they describe as a cynical race ploy. They say the

project’s developer, Forest City Ratner, has deliberately stirred up an imagined

racial divide over the project, enlisting its black allies to falsely cast

affluent white residents as the chief source of opposition and as insensitive to

the needs of black Brooklynites.

“I think race was used from Day 1 to window-dress the project,” said the Rev.

Clinton Miller, pastor of Brown Memorial Baptist Church in Fort Greene.

Bruce C. Ratner, Forest City’s chief executive, is white, as are most of his

executives. Several local community organizations with black leaders receive

funds from the developer as part of a “community benefits agreement” they

negotiated last year.

But a closer look at the coalitions lined up for and against the project, and

the arguments they have mustered, suggests that Atlantic Yards has drawn no true

color line in Brooklyn, but only a blur of intersecting agendas, opinions and

constituencies, both black and white.

The project, designed by Frank Gehry, would radically alter the neighborhoods

near Downtown Brooklyn where it would be built, with residential and office

towers and a basketball arena for the Nets. Proponents say the project would

provide more jobs and low-cost housing where they are urgently needed.

When pressed, however, nearly all of those involved in the debate played down

the suggestion that opinion on Atlantic Yards cleaves to any purely racial

contour.

They point out that the project’s leading political booster, Borough President

Marty Markowitz, is white, and its leading opponent, Councilwoman Letitia James,

is black.

In neighborhoods around the project site, they say, the pressures of class and

gentrification have been as potent as race — though both sides say they believe

those pressures favor their view of the project.

“Some of my friends are in the opposition, and they’re blacker than I am,” said

the Rev. Herbert Daughtry, a supporter and well-known Brooklyn pastor. “It ain’t

a straight race question.”

Joe DePlasco, a spokesman for the developer, denied in a statement that Forest

City had tried to use race to build public support for the project, or to

isolate opponents.

“People say a lot of things, but at the end of the day you can only do what you

think is right,” he said in a statement.

“From the start,” the statement continued, “we have reached out to diverse

groups from all over Brooklyn — from Crown Heights to Marine Park from Sunset

Park to Park Slope — to ensure that this project reflects the realities of life

in this borough and addresses the unprecedented need for affordable housing,

local jobs, small business development, health care, educational and training

programs.”

He added, “Atlantic Yards is, among other things, all about inclusion, and we

have worked hard to make it that way.”

Forest City, which is also the development partner in building a new Midtown

headquarters for The New York Times, would not comment directly on past

statements by its supporters.

In recent conversations, however, many of those involved in the Atlantic Yards

debate spoke at length about the role that race has played — and not played — in

shaping opinion on the project.

Though Brooklyn as a whole has been losing white residents for decades, the

number living near the project site — in neighborhoods like Fort Greene, Boerum

Hill and Prospect Heights — has grown steadily in recent years, according to

census data.

Those new arrivals are more likely to be affluent and highly educated,

especially compared with residents of the nearby public housing projects, where

most residents are black and many are unemployed.

As white transplants have boosted the area’s median incomes, they have also

forced up housing prices. In Fort Greene, for example, which borders the project

site to the north, average apartment prices rose faster from 2004 to 2005 than

in any other Brooklyn neighborhood.

“If you live nearby, you have a nice home and you have a job, you’re probably

not that excited by the benefits, and you’re swamped by the drawbacks,” said

Brad Lander, director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, citing the

project’s potential to worsen traffic and overshadow the brownstone communities

nearby.

“If you live a little farther away, and you don’t have a job and a nice house,

then you probably get a lot more of the benefits,” Mr. Lander added. “None of

that is about race per se. But when you layer on that the people who live nearby

are more likely to be whiter and wealthier, and the people who live farther out

are more likely to be people of color without good jobs or housing, the race

elements have become stronger.”

That is one reason, say opponents and supporters alike, for the high-level

interest in the project among the area’s black working-class and poor residents.

Thousands of people, most of them black, packed a July information session about

the project’s subsidized housing.

“The devil could bring in a project and say it’s jobs and affordable housing,

and some of us will go for it, because we’re on a survival level,” said City

Councilman Charles Barron.

But Mr. Barron also calls the project “instant gentrification,” a view shared by

many opponents.

Atlantic Yards would include a substantial portion of subsidized housing for

families at different income levels; but only about one-seventh of the project’s

roughly 6,500 housing units would be classified as affordable for tenants making

less than half of the median income for the New York City area.

Mr. Barron and other critics say a different project could provide as much or

more moderately priced housing, with less negative impact on the area.

Most recent public polls about the project show supporters outnumbering

opponents. But those polls have generally been too small to reliably measure

sentiment among specific ethnic or racial groups in Brooklyn or the city as a

whole.

In interviews, activists on both sides said they believed support and opposition

cut across racial and class lines.

But some in the debate previously expressed less benign views.

Last year, James E. Caldwell, the president of Brooklyn United for Innovative

Local Development, a job-training group known as Build, said it would be a

“conspiracy against blacks” if Forest City did not win its bid for rights to

build over the railyards on the site. Bertha Lewis, the New York executive

director of Acorn, a national advocacy group for low-income people, attributed

concern over the project to “white liberals.”

Interviewed recently, both Mr. Caldwell and Ms. Lewis backed away from those

remarks. “Everybody said crazy things on both sides,” Ms. Lewis said. “I’ve

apologized to folks, and folks have apologized to me.”

Both Build and Acorn — as well as a group Mr. Daughtry heads — receive funds