|

History > 2006 > USA > Economy (IV)

GAO chief warns

economic disaster looms

Updated 10/29/2006 12:35 AM ET

By Matt Crenson, Associated Press

USA Today

AUSTIN — David Walker sure talks like he's

running for office. "This is about the future of our country, our kids and

grandkids," the comptroller general of the United States warns a packed hall at

Austin's historic Driskill Hotel. "We the people have to rise up to make sure

things get changed."

But Walker doesn't want, or need, your vote

this November. He already has a job as head of the Government Accountability

Office, an investigative arm of Congress that audits and evaluates the

performance of the federal government.

Basically, that makes Walker the nation's accountant-in-chief. And the

accountant-in-chief's professional opinion is that the American public needs to

tell Washington it's time to steer the nation off the path to financial ruin.

From the hustings and the airwaves this campaign season, America's political

class can be heard debating Capitol Hill sex scandals, the wisdom of the war in

Iraq and which party is tougher on terror. Democrats and Republicans talk of

cutting taxes to make life easier for the American people.

What they don't talk about is a dirty little secret everyone in Washington

knows, or at least should. The vast majority of economists and budget analysts

agree: The ship of state is on a disastrous course, and will founder on the

reefs of economic disaster if nothing is done to correct it.

There's a good reason politicians don't like to talk about the nation's

long-term fiscal prospects. The subject is short on political theatrics and long

on complicated economics, scary graphs and very big numbers. It reveals serious

problems and offers no easy solutions. Anybody who wanted to deal with it

seriously would have to talk about raising taxes and cutting benefits, nasty

nostrums that might doom any candidate who prescribed them.

"There's no sexiness to it," laments Leita Hart-Fanta, an accountant who has

just heard Walker's pitch. She suggests recruiting a trusted celebrity — maybe

Oprah — to sell fiscal responsibility to the American people.

Walker doesn't want to make balancing the federal government's books sexy — he

just wants to make it politically palatable. He has committed to touring the

nation through the 2008 elections, talking to anybody who will listen about the

fiscal black hole Washington has dug itself, the "demographic tsunami" that will

come when the baby boom generation begins retiring and the recklessness of

borrowing money from foreign lenders to pay for the operation of the U.S.

government.

"He can speak forthrightly and independently because his job is not in jeopardy

if he tells the truth," said Isabel Sawhill, a senior fellow in economic studies

at the Brookings Institution.

Walker can talk in public about the nation's impending fiscal crisis because he

has one of the most secure jobs in Washington. As comptroller general of the

United States — basically, the government's chief accountant — he is serving a

15-year term that runs through 2013.

This year Walker has spoken to the Union League Club of Chicago and the Rotary

Club of Atlanta, the Sons of the American Revolution and the World Future

Society. But the backbone of his campaign has been the Fiscal Wake-up Tour, a

traveling roadshow of economists and budget analysts who share Walker's concern

for the nation's budgetary future.

"You can't solve a problem until the majority of the people believe you have a

problem that needs to be solved," Walker says.

Polls suggest that Americans have only a vague sense of their government's

long-term fiscal prospects. When pollsters ask Americans to name the most

important problem facing America today — as a CBS News/New York Times poll of

1,131 Americans did in September — issues such as the war in Iraq, terrorism,

jobs and the economy are most frequently mentioned. The deficit doesn't even

crack the top 10.

Yet on the rare occasions that pollsters ask directly about the deficit, at

least some people appear to recognize it as a problem. In a survey of 807

Americans last year by the Pew Center for the People and the Press, 42% of

respondents said reducing the deficit should be a top priority; another 38% said

it was important but a lower priority.

So the majority of the public appears to agree with Walker that the deficit is a

serious problem, but only when they're made to think about it. Walker's

challenge is to get people not just to think about it, but to pressure

politicians to make the hard choices that are needed to keep the situation from

spiraling out of control.

To show that the looming fiscal crisis is not a partisan issue, he brings along

economists and budget analysts from across the political spectrum. In Austin,

he's accompanied by Diane Lim Rogers, a liberal economist from the Brookings

Institution, and Alison Acosta Fraser, director of the Roe Institute for

Economic Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

"We all agree on what the choices are and what the numbers are," Fraser says.

Their basic message is this: If the United States government conducts business

as usual over the next few decades, a national debt that is already $8.5

trillion could reach $46 trillion or more, adjusted for inflation. That's almost

as much as the total net worth of every person in America — Bill Gates, Warren

Buffett and those Google guys included.

A hole that big could paralyze the U.S. economy; according to some projections,

just the interest payments on a debt that big would be as much as all the taxes

the government collects today.

And every year that nothing is done about it, Walker says, the problem grows by

$2 trillion to $3 trillion.

People who remember Ross Perot's rants in the 1992 presidential election may

think of the federal debt as a problem of the past. But it never really went

away after Perot made it an issue, it only took a breather. The federal

government actually produced a surplus for a few years during the 1990s, thanks

to a booming economy and fiscal restraint imposed by laws that were passed early

in the decade. And though the federal debt has grown in dollar terms since 2001,

it hasn't grown dramatically relative to the size of the economy.

But that's about to change, thanks to the country's three big entitlement

programs — Social Security, Medicaid and especially Medicare. Medicaid and

Medicare have grown progressively more expensive as the cost of health care has

dramatically outpaced inflation over the past 30 years, a trend that is expected

to continue for at least another decade or two.

And with the first baby boomers becoming eligible for Social Security in 2008

and for Medicare in 2011, the expenses of those two programs are about to

increase dramatically due to demographic pressures. People are also living

longer, which makes any program that provides benefits to retirees more

expensive.

Medicare already costs four times as much as it did in 1970, measured as a

percentage of the nation's gross domestic product. It currently comprises 13% of

federal spending; by 2030, the Congressional Budget Office projects it will

consume nearly a quarter of the budget.

Economists Jagadeesh Gokhale of the American Enterprise Institute and Kent

Smetters of the University of Pennsylvania have an even scarier way of looking

at Medicare. Their method calculates the program's long-term fiscal shortfall —

the annual difference between its dedicated revenues and costs — over time.

By 2030 they calculate Medicare will be about $5 trillion in the hole, measured

in 2004 dollars. By 2080, the fiscal imbalance will have risen to $25 trillion.

And when you project the gap out to an infinite time horizon, it reaches $60

trillion.

Medicare so dominates the nation's fiscal future that some economists believe

health care reform, rather than budget measures, is the best way to attack the

problem.

"Obviously health care is a mess," says Dean Baker, a liberal economist at the

Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington think tank. "No one's been

willing to touch it, but that's what I see as front and center."

Social Security is a much less serious problem. The program currently pays for

itself with a 12.4% payroll tax, and even produces a surplus that the government

raids every year to pay other bills. But Social Security will begin to run

deficits during the next century, and ultimately would need an infusion of $8

trillion if the government planned to keep its promises to every beneficiary.

Calculations by Boston University economist Lawrence Kotlikoff indicate that

closing those gaps — $8 trillion for Social Security, many times that for

Medicare — and paying off the existing deficit would require either an immediate

doubling of personal and corporate income taxes, a two-thirds cut in Social

Security and Medicare benefits, or some combination of the two.

Why is America so fiscally unprepared for the next century? Like many of its

citizens, the United States has spent the last few years racking up debt instead

of saving for the future. Foreign lenders — primarily the central banks of

China, Japan and other big U.S. trading partners — have been eager to lend the

government money at low interest rates, making the current $8.5-trillion deficit

about as painful as a big balance on a zero-percent credit card.

In her part of the fiscal wake-up tour presentation, Rogers tries to explain why

that's a bad thing. For one thing, even when rates are low a bigger deficit

means a greater portion of each tax dollar goes to interest payments rather than

useful programs. And because foreigners now hold so much of the federal

government's debt, those interest payments increasingly go overseas rather than

to U.S. investors.

More serious is the possibility that foreign lenders might lose their enthusiasm

for lending money to the United States. Because treasury bills are sold at

auction, that would mean paying higher interest rates in the future. And it

wouldn't just be the government's problem. All interest rates would rise, making

mortgages, car payments and student loans costlier, too.

A modest rise in interest rates wouldn't necessarily be a bad thing, Rogers

said. America's consumers have as much of a borrowing problem as their

government does, so higher rates could moderate overconsumption and encourage

consumer saving. But a big jump in interest rates could cause economic

catastrophe. Some economists even predict the government would resort to

printing money to pay off its debt, a risky strategy that could lead to runaway

inflation.

Macroeconomic meltdown is probably preventable, says Anjan Thakor, a professor

of finance at Washington University in St. Louis. But to keep it at bay, he

said, the government is essentially going to have to renegotiate some of the

promises it has made to its citizens, probably by some combination of tax

increases and benefit cuts.

But there's no way to avoid what Rogers considers the worst result of racking up

a big deficit — the outrage of making our children and grandchildren repay the

debts of their elders.

"It's an unfair burden for future generations," she says.

You'd think young people would be riled up over this issue, since they're the

ones who will foot the bill when they're out in the working world. But students

take more interest in issues like the Iraq war and gay marriage than the federal

government's finances, says Emma Vernon, a member of the University of Texas

Young Democrats.

"It's not something that can fire people up," she says.

The current political climate doesn't help. Washington tends to keep its fiscal

house in better order when one party controls Congress and the other is in the

White House, says Sawhill.

"It's kind of a paradoxical result. Your commonsense logic would tell you if one

party is in control of everything they should be able to take action," Sawhill

says.

But the last six years of Republican rule have produced tax cuts, record

spending increases and a Medicare prescription drug plan that has been widely

criticized as fiscally unsound. When President Clinton faced a Republican

Congress during the 1990s, spending limits and other legislative tools helped

produce a surplus.

So maybe a solution is at hand.

"We're likely to have at least partially divided government again," Sawhill

said, referring to predictions that the Democrats will capture the House, and

possibly the Senate, in next month's elections.

But Walker isn't optimistic that the government will be able to tackle its

fiscal challenges so soon.

"Realistically what we hope to accomplish through the fiscal wake-up tour is

ensure that any serious candidate for the presidency in 2008 will be forced to

deal with the issue," he says. "The best we're going to get in the next couple

of years is to slow the bleeding."

GAO

chief warns economic disaster looms, UT, 29.10.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2006-10-28-economic-disaster_x.htm

Russia Led Arms Sales to Developing World in ’05

October 29, 2006

The New York Times

By THOM SHANKER

WASHINGTON, Oct. 28 — Russia surpassed the United

States in 2005 as the leader in weapons deals with the developing world, and its

new agreements included selling $700 million in surface-to-air missiles to Iran

and eight new aerial refueling tankers to China, according to a new

Congressional study.

Those weapons deals were part of the highly competitive global arms bazaar in

the developing world that grew to $30.2 billion in 2005, up from $26.4 billion

in 2004. It is a market that the United States has regularly dominated.

Russia’s agreements with Iran are not the biggest part of its total sales —

India and China are its principal buyers. But the sales to improve Iran’s

air-defense system are particularly troubling to the United States because they

would complicate the task of Pentagon planners should the president order

airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear weapons facilities.

The Bush administration has vowed a diplomatic solution in dealing with Iran.

But as United Nations diplomats argue over potential sanctions against Iran for

its nuclear ambitions, Russian officials have expressed reluctance to vote for

the most stringent economic sanctions, partly owing to Moscow’s extensive trade

relations with Tehran.

Russia’s weapons sales to China also worry Pentagon planners. Although China has

joined the United States in partnership to press for a resumption of six-party

talks to end North Korea’s nuclear weapons program after its recent test, Taiwan

remains a potential flash point between Beijing and Washington.

Thus, China’s ability to refuel its attack planes and bombers to enable them to

fly farther from Chinese soil could require the United States Navy to operate

even farther out to sea should the United States military be called to deal with

a crisis in the Taiwan Strait. That would have an impact on the range and number

of air missions of United States Navy aircraft launched from carriers.

Details of the specific weapons deals in the global arms trade last year are

included in an annual study by the Congressional Research Service that is

considered the most thorough compilation of statistics available in an

unclassified form. The report was delivered to members of Congress on Friday.

Among other arms transfers described in the study was a statistic that a single,

unnamed nation — but one identified separately by Pentagon and other

administration officials to be North Korea — shipped about 40 ballistic missiles

to other nations in the four-year period ending in 2005, the only nation to have

done so. Transfers of these weapons are prohibited under international

agreements to control the trade of ballistic missiles.

United Nations sanctions passed earlier this month after the North Korean

nuclear test include a new and specific ban on trade or transport of ballistic

missiles and missile parts to or from North Korea.

The report, entitled “Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing Nations,” found

that Russia’s arms agreements with the developing world totaled $7 billion in

2005, an increase from its $5.4 billion in sales in 2004. That figure surpassed

the United States’ annual sales agreements to the developing world for the first

time since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

France ranked second in arms transfer agreements to developing nations, with

$6.3 billion, and the United States was third, with $6.2 billion.

The leading buyer in the developing world in 2005 was India, with $5.4 billion

in weapons purchases, followed by Saudi Arabia with $3.4 billion and China with

$2.8 billion.

The total value of all arms sales deals worldwide, when counting both developing

and developed nations, in 2005 was $44.2 billion.

The Russian sales in 2005 included 29 of the SA-15 Gauntlet surface-to-air

missile systems for Iran; Russia also signed deals to upgrade Iran’s Su-24

bombers and MIG-29 fighter aircraft, as well as its T-72 battle tanks.

“For a period of time, in the mid-1990s, the Russian government agreed not to

make new advanced weapons sales to the Iran government,” wrote Richard F.

Grimmett, author of the study by the Congressional Research Service, a division

of the Library of Congress. “That agreement has since been rescinded by Russia.

As the U.S. focuses increasing attention on Iran’s efforts to enhance its

nuclear as well as conventional military capabilities, major arms transfers to

Iran continue to be a matter of concern.”

Russia also agreed in 2005 to sell China eight of the IL-78M aerial refueling

tanker aircraft, according to the study.

In 2005, the United States led in total arms transfer agreements, when deals to

both developed and developing nations are combined. The total was $12.8 billion,

down from $13.2 billion in 2004.

The report charted no blockbuster military sales deals by the United States in

2005, and the total in many ways was reached by sales of spare parts for weapons

purchased under previous contracts.

France ranked second in total sales, with $7.9 billion, up from $2.2 billion in

2004. Russia was third when sales to developing and developed nations were

combined, with $7.4 billion, up from $5.6 billion in 2004.

The study uses figures in 2005 dollars, with amounts for previous years adjusted

to account for inflation.

Russia Led Arms Sales to Developing World in ’05, NYT, 29.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/world/europe/29weapons.html?hp&ex=1162184400&en=ee804ed2509262d6&ei=5094&partner=homepage

U.S. Jobs Shape Condoms’ Role in

Foreign Aid

October 29, 2006

The New York Times

By CELIA W. DUGGER

EUFAULA, Alabama — Here in this courtly,

antebellum town, Alabama’s condom production has survived an onslaught of Asian

competition, thanks to the patronage of straitlaced congressmen from this Bible

Belt state.

Behind the scenes, the politicians have ensured that companies in Alabama won

federal contracts to make billions of condoms over the years for AIDS prevention

and family planning programs overseas, though Asian factories could do the job

at less than half the cost.

In recent years, the state’s condom manufacturers fell hundreds of millions of

condoms behind on orders, and the federal aid agency began buying them from

Asia. The use of Asian-made condoms has contributed to layoffs that are coming

next month.

But Senator Jeff Sessions, Republican of Alabama, has quietly pressed to

maintain the unqualified priority for American-made condoms and is likely to

prevail if the past is any guide.

“What’s wrong with helping the American worker at the same time we are helping

people around the world?” asked the senator’s spokesman, Michael Brumas.

That question goes to the heart of an intensifying debate among wealthy nations

about to what degree foreign aid is about saving jobs at home or lives abroad.

Britain, Ireland and Norway have all sought to make aid more cost effective by

opening contracts in their programs to fight global poverty to international

competition. The United States, meanwhile, continues to restrict bidding on

billions of dollars worth of business to companies operating in America, and not

just those that make condoms.

The wheat to feed the starving must be grown in United States and shipped to

Africa, enriching agribusiness giants like Archer Daniels Midland and Cargill.

The American consulting firms that carry out antipoverty programs abroad —

dubbed beltway bandits by critics — do work that some advocates say local groups

in developing countries could often manage at far less cost.

The history of the federal government’s condom purchases embodies the tradeoffs

that characterize foreign aid American-style. Alabama’s congressmen have long

preserved several hundred factory jobs here by insisting that the United States

Agency for International Development buy condoms made here, though, probably in

a nod to their conservative constituencies, most have typically done so

discreetly.

Those who favor tying aid to domestic interests say that it not only preserves

jobs and supports American companies, but helps ensure broad political support

for foreign aid, which is not always popular.

On the other hand, skepticism of foreign aid is frequently rooted in the

perception that the money is not well spent. Blame often falls on corrupt

leaders in poor countries, but aid from rich nations with restrictions requiring

it to be spent in the donor country can also reduce effectiveness.

The United States government, the world’s largest donor of condoms, has bought

more than nine billion condoms over the past two decades. Under President Bush’s

global AIDS plan, which dedicates billions of dollars to fight the epidemic, a

third of the money for prevention must go to promoting abstinence. But that

leaves two-thirds for other programs, so the federal government’s distribution

of condoms has risen, to over 400 million a year.

Over the years, Usaid could have afforded even more condoms — among the most

effective methods for slowing the spread of AIDS — if it had it bought them from

the lowest bidders on the world market, as have the United Nations Population

Fund and many other donors.

Randall L. Tobias, who heads Usaid, declined through a spokesman to be

interviewed on this topic. His predecessor, Andrew Natsios, sought to weaken the

hold of what he sometimes called a cartel of domestic interest groups over

foreign aid. He tried, for example, to persuade Congress to allow the purchase

of some African food to feed Africa’s hungry. Congress killed that proposal last

year and again this year.

Hilary Benn, Britain’s secretary of state for international development, said in

an interview that in 2001 his country untied its aid from requirements that only

British firms could bid for international antipoverty work.

“If you untie aid, it’s 100 percent clear you’re giving aid to reduce poverty

and not to benefit your own country’s commercial interests,” he said.

In recent years, most of the low-end condom business has moved to Asia,

including Australia-based Ansell, which used to have plants in Alabama. American

makers cannot compete with Asia on price — unless they have the federal

contract.

The last American factory making condoms for Usaid sits anonymously in a

pine-shaded industrial park here in Eufaula. Inside a modern, low-slung building

owned by Alatech Healthcare, ingenious contraptions almost as long as a football

field repeatedly dip 16,000 phallic-shaped bulbs into vats of latex, with the

capacity to turn out a billion condoms a year.

The equation of need is never straightforward. Africa’s need to forestall its

slow-motion catastrophe of AIDS deaths is vast. But there is need here, too.

Most of the 260 people employed at this factory and the company’s packaging

plant in Slocomb are women, some the children of sharecroppers and textile

factory workers, many of them struggling to support families on $7 to $8 an

hour.

The most vulnerable among them — single mothers and older women with scant

education — are the most fearful of foreign competition. All feel the looming

threat.

“It’s cheaper, yeah,” said Lisa Jackson, 42, a worker in the packaging plant.

“But we Americans should have first choice. We need our jobs to stay in America.

We got to feed our families. I just wish it had never come to sending

manufacturing jobs overseas.”

From 2003 to 2005, Alatech and one other company making condoms for Usaid fell

behind on their orders, agency officials said. Last year, the other company went

bankrupt. So Usaid ordered condoms from Asia, the first of which were shipped

last year. With only a single American company still in line for the federal

contract, agency officials are wary of ruling out Asian suppliers.

At such moments in the past, Alabama’s politicians have come to the rescue of

the state’s condom industry. This time was no exception.

Senator Richard C. Shelby, a Republican on the Appropriations Committee, had a

provision tucked into the 2004 budget bill requiring that Usaid buy only

American-made condoms to the extent possible, given cost and availability. His

spokeswoman, Kate Boyd, said the agency did not tell him it was worried about

the relative cost of American and Asian-made condoms.

Senator Sessions wrote Usaid a letter last year saying it should purchase

condoms from foreign producers only after it had bought all the condoms American

companies could make, noting it was “extremely important to jobs in my state.”

Usaid assured the senator in writing that it “remains committed to prioritizing

domestic suppliers.”

On the strength of that, Alatech bought the more modern Eufaula plant from its

bankrupt rival. Without the government contract, the company’s president, Larry

Povlacs, said, Alatech would go out of business.

In interviews, agency officials were noncommittal about whether they would halt

all purchases in Asia. Condoms made there cost around 2 cents each, opposed to

about 5 cents for those made here.

“At the end of the day, it’s all a political process,” Bob Lester, who recently

retired after 31 years as a lawyer at Usaid, said of such decisions. “The

foreign aid program has very few rabbis. Why make enemies when you don’t have

to?”

Duff Gillespie, a retired senior Usaid official who is now a professor at the

Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, said that over the years officials at

Usaid raised the prospect of foreign competition to tamp down what he called

“the greed factor” of Alabama condom manufacturers.

But whenever the staff pushed to buy in Asia, Alabama politicians pushed right

back.

During the Reagan years, the offices of two Alabamans, Representative William

Dickinson, a Republican, and Senator Howell Heflin, a Democrat, caught wind of

one such move. Mike Houston, chief of staff to Senator Heflin, recalled being

tipped off by Mr. Dickinson’s chief of staff.

“He says, ‘Well, A.I.D. is going to buy condoms from Korea,’ ” Mr. Houston

recalled. “ ‘The reason is they can get three condoms for the price of one that

they’re paying us.’ ” Mr. Houston said he asked in amazement, “You mean we’re

making rubbers in Alabama?”

The congressmen’s staffs threatened to introduce amendments to require that

condoms be made in America. The agency backed off.

Further attempts to open up bidding proved fruitless. Representative Jim

McDermott, a Democrat from Washington State, had seen the devastation of AIDS

firsthand in the 1980s as a State Department medical officer in Africa. But he

said he could not break what he called the “stranglehold” of Alabama congressmen

on the condom rules.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Representative Sonny Callahan, a Republican from

Alabama, served as chairman of the Appropriations subcommittee that shaped

Usaid’s budget. Brian Atwood, who headed Usaid in those years, said no

administrator “in his right mind” would have tried to cut Alabama out of the

condom contract at a time when many Republicans were deeply hostile to foreign

aid.

Then in 2001, after decades of negotiation, the United States and other wealthy

donor nations reached a nonbinding agreement to open at least some foreign aid

contracts to all qualified bidders. Included were those for commodities bound

for the world’s poorest nations.

Usaid decided the agreement did not apply to condoms since some went to more

advanced developing countries. Alabama’s manufacturers kept the condom business

once again.

William Nicol, who heads the poverty reduction division of the Development

Assistance Committee at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development, a group of economically advanced countries, scoffed at Usaid’s

interpretation. “That’s rubbish,” he said in a telephone interview.

The condom companies’ inability in recent years to fulfill Usaid’s orders

accomplished what the gentleman’s agreement did not: the entry of Asian

competitors.

Usaid has asked Alatech to make 201 million condoms next year, less than half of

this year’s order, and ordered another 100 million made in Korea and China.

Come Nov. 15, Alatech will lay off more than half its work force. Those jobs

fell victim to Usaid’s smaller orders for condoms, foreign competition and

automation.

The reactions of these workers ranged from philosophical to panicked.

One, Garry Appling, a 41-year-old single mother, has worked before as a

$6-an-hour cashier at Krystal, the fast food restaurant, and another at $7.15 an

hour in a chicken processing plant. She said her 10-year-old daughter, Anterria,

worries that she will have to go back to the chicken plant, a place so cold and

wet Ms. Appling often fell ill.

But even facing her own impending job loss, Ms. Appling took a moment to

empathize with the women making condoms on the other side of the world.

“We need a job — I guess they do, too,” she said, during a brief pause from

feeding condoms into an intricate, rotating, whooshing machine that tested them

for holes. “It’s sad.

“At the same time, the United States can’t just keep helping overseas. They’ve

got to help us, too.”

U.S.

Jobs Shape Condoms’ Role in Foreign Aid, NYT, 29.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/world/29condoms.html?hp&ex=1162184400&en=a92173d62cb1edef&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Businesses Seek Protection on Legal Front

October 29, 2006

The New York Times

By STEPHEN LABATON

WASHINGTON, Oct. 28 — Frustrated with laws and

regulations that have made companies and accounting firms more open to lawsuits

from investors and the government, corporate America — with the encouragement of

the Bush administration — is preparing to fight back.

Now that corruption cases like Enron and WorldCom are falling out of the news,

two influential industry groups with close ties to administration officials are

hoping to swing the regulatory pendulum in the opposite direction. The groups

are drafting proposals to provide broad new protections to corporations and

accounting firms from criminal cases brought by federal and state prosecutors as

well as a stronger shield against civil lawsuits from investors.

Although the details are still being worked out, the groups’ proposals aim to

limit the liability of accounting firms for the work they do on behalf of

clients, to force prosecutors to target individual wrongdoers rather than entire

companies, and to scale back shareholder lawsuits.

The groups hope to reduce what they see as some burdens imposed by the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act, landmark post-Enron legislation adopted in 2002. The law,

which placed significant new auditing and governance requirements on companies,

gave broad discretion for interpretation to the Securities and Exchange

Commission. The groups are also interested in rolling back rules and policies

that have been on the books for decades.

To alleviate concerns that the new Congress may not adopt the proposals —

regardless of which party holds power in the legislative branch next year — many

are being tailored so that they could be adopted through rulemaking by the

S.E.C. and enforcement policy changes at the Justice Department.

The proposals will begin to be laid out in public shortly after Election Day,

members of the groups said in recent interviews. One of the committees was

formed by the United States Chamber of Commerce and until recently was headed by

Robert K. Steel.

Mr. Steel was sworn in last Friday as the new Treasury undersecretary for

domestic finance, and he is the senior official in the department who will be

formulating the Treasury’s views on the issues being studied by the two groups.

The second committee was formed by the Harvard Law professor Hal S. Scott, along

with R. Glenn Hubbard, a former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for

President Bush, and John L. Thornton, a former president of Goldman Sachs, where

he worked with Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson Jr.

That group has colloquially become known around Washington as the Paulson

Committee because the relatively new Treasury secretary issued an encouraging

statement when it was formed last month. But administration officials said

Friday that he was not playing a role in the group’s deliberations.

Its members include Donald L. Evans, a former commerce secretary who remains a

close friend of President Bush; Samuel A. DiPiazza Jr., chief executive of

PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accounting giant; Robert R. Glauber, former chairman

and chief executive of the National Association of Securities Dealers, the

private group that oversees the securities industry; and the chief executives of

DuPont, Office Depot and the CIT Group.

Jennifer Zuccarelli, a spokeswoman at the Treasury Department, said on Friday

that no decision had been made about which recommendations would be supported by

the administration.

“While the department always wants to hear new ideas from academic and industry

thought leaders, especially to encourage the strength of the U.S. capital

markets, Treasury is not a member of these committees and is not collaborating

on any findings,” Ms. Zuccarelli said.

But another official and committee members noted that Mr. Paulson had recently

pressed the groups in private discussions to complete their work so it could be

rolled out quickly after the November elections.

Moreover, committee members say that they expect many of their recommendations

will be used as part of an overall administration effort to limit what they see

as overzealous state prosecutions by such figures as the New York State attorney

general Elliot Spitzer and abusive class action lawsuits by investors. The

groups will also attempt to lower what they see as the excessive costs

associated with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

Their critics, however, see the effort as part of a plan to cater to the most

well-heeled constituents of the administration and insulate politically

connected companies from prosecution at the expense of investors.

One consideration in drafting the proposals has been the chain of events at

Arthur Andersen, the accounting firm that was convicted in 2002 of obstruction

of justice for shredding Enron-related documents; the conviction was overturned

in 2005 by the Supreme Court. The proposals being drafted would aim to limit the

liability of auditing firms and include a policy shift to make it harder for

prosecutors to bring cases against individuals and companies.

Even though Arthur Andersen played a prominent role in various corporate

scandals, some business and legal experts have criticized the decision by the

Bush administration to bring a criminal case that had the effect of shutting the

firm down.

The proposed policies would emphasize the prosecution of culpable individuals

rather than corporations and auditing firms. That shift could prove difficult

for prosecutors because it is often harder to find sufficient evidence to show

that specific people at a company were the ones who knowingly violated a law.

One proposal would recommend that the Justice Department sharply curtail its

policy of forcing companies under investigation to withhold paying the legal

fees of executives suspected of violating the law. Another one would require

some investor lawsuits to be handled by arbitration panels, which are

traditionally friendlier to defendants.

In an interview last week with Bloomberg News, Mr. Paulson repeated his

criticism of the Sarbanes-Oxley law. While it had done some good, he said, it

had contributed to “an atmosphere that has made it more burdensome for companies

to operate.”

Mr. Paulson also repeated a line from his first speech, given at Columbia

Business School last August, where he said, “Often the pendulum swings too far

and we need to go through a period of readjustment.”

Some experts see Mr. Paulson’s complaint as a step backward.

“This is an escalation of the culture war against regulation,” said James D.

Cox, a securities and corporate law professor at Duke Law School. He said many

of the proposals, if adopted, “would be a dark day for investors.”

Professor Cox, who has studied 600 class action lawsuits over the last decade,

said it was difficult to find “abusive or malicious” cases, particularly in

light of new laws and court decisions that had made it more difficult to file

such suits.

The number of securities class action lawsuits has dropped substantially in each

of the last two years, he noted, arguing that the impact of the proposals from

the business groups would be that “very few people would be prosecuted.”

People involved in the committees said that the timing of the proposals was

being dictated by the political calendar: closely following Election Day and as

far away as possible from the 2008 elections.

Mr. Hubbard, who is now dean of Columbia Business School, said the committee he

helps lead would focus on the lack of proper economic foundation for a number of

regulations. Most changes will be proposed through regulation, he said, because

“the current political environment is simply not ripe for legislation.”

But the politics of changing the rules do not break cleanly along party lines.

While some prominent Democrats would surely attack the pro-business efforts,

there are others who in the past have been sympathetic.

People involved in the committees’ work said that their objective was to improve

the attractiveness of American capital-raising markets by scaling back rules

whose costs outweigh their benefits.

“We think the legal liability issues are the most serious ones,” said Professor

Scott, the director of the committee singled out by Mr. Paulson. “Companies

don’t want to use our markets because of what they see as the substantial, and

in their view excessive, liability.”

Committee officials disputed the notion that they were simply catering to

powerful business interests seeking to benefit from loosening regulations that

could wind up hurting investors.

“It’s unfortunate to the extent that this has been politicized,” said Robert E.

Litan, a former Justice Department official and senior fellow at the Brookings

Institution who is overseeing the committee’s legal liability subgroup. “The

objectives are clearly not to gut such reforms as Sarbanes-Oxley. I’m for

cost-effective regulation.”

The main Sarbanes-Oxley provision that both committees are focusing on is a part

that is commonly called Section 404, which requires audits of companies’

internal financial controls. Some business experts praise this section as having

made companies more transparent and better managed, but many smaller companies

call the section too costly and unnecessary.

Members of the two committees said that they had reached a consensus that

Section 404, along with greater threat of investor lawsuits and government

prosecutions, had discouraged foreign companies from issuing new stock on

exchanges in the United States in recent months.

The committee members said that an increase in stock offerings abroad was

evidence that the American liability system and tougher auditing standards were

taking a toll on the competitiveness of American markets. But others see

different reasons for the trend and few links to liability and accounting rules.

Bill Daley, a former commerce secretary in the Clinton administration who is the

co-chairman of the Chamber of Commerce group, expects proposed changes to

liability standards for accounting firms and corporations to draw the most flak.

But he said that the changes affecting accounting firms are of paramount

importance to prevent the further decline in competition. Only four major firms

were left after Andersen’s collapse.

Another contentious issue concerns a proposal to eliminate the use of a broadly

written and long-established anti-fraud rule, known as Rule 10b-5, that allows

shareholders to sue companies for fraud. The change could be accomplished by a

vote of the S.E.C.

John C. Coffee, a professor of securities law at Columbia Law School and an

adviser to the Paulson Committee, said that he had recommended that the S.E.C.

adopt the exception to Rule 10b-5 so that only the commission could bring such

lawsuits against corporations.

But other securities law experts warned that such a move would extinguish a

fundamental check on corporate malfeasance.

“It would be a shocking turning back to say only the commission can bring fraud

cases,” said Harvey J. Goldschmid, a former S.E.C. commissioner and law

professor at Columbia University. “Private enforcement is a necessary supplement

to the work that the S.E.C. does. It is also a safety valve against the

potential capture of the agency by industry.”

Businesses Seek Protection on Legal Front, NYT, 29.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/business/29corporate.html?hp&ex=1162184400&en=9358599aad440557&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Democrats Get Late Donations From Business

October 28, 2006

The New York Times

By JEFF ZELENY and ARON PILHOFER

WASHINGTON, Oct. 27 — Corporate America is

already thinking beyond Election Day, increasing its share of last-minute

donations to Democratic candidates and quietly devising strategies for how to

work with Democrats if they win control of Congress.

The shift in political giving, for the first 18 days of October, has not been

this pronounced in the final stages of a campaign since 1994, when Republicans

swept control of the House for the first time in four decades.

Though Democratic control of either chamber of Congress is far from certain, the

prospect of a power shift is leading interest groups to begin rethinking

well-established relationships, with business lobbyists going as far as finding

potential Democratic allies in the freshman class — even if they are still

trying to defeat them on the campaign trail — and preparing to extend an olive

branch the morning after the election.

Lobbyists, some of whom had fallen out of the habit of attending Democratic

events, are even talking about making their way to the Sonnenalp Resort in Vail,

Colo., where Representative Nancy Pelosi of California is holding a Speaker’s

Club ski getaway on Jan. 3. It is an annual affair, but the gathering’s title

could be especially apt for Ms. Pelosi, the House minority leader, who will be

on hand to accept $15,000 checks, and could, if everything breaks her way,

become the first woman to be House speaker.

“Attendance will be high,” said Steve Elmendorf, a former Democratic

Congressional aide who has a long list of business lobbying clients. “All

Democratic events will see a big increase next year, no question.”

While business groups contained their Democratic contributions to only a handful

of candidates throughout the year, a shifting political climate and an expanding

field of competitive Congressional races has drawn increased donations from

corporate political action committees.

For the first nine months of the year, for example, Pfizer’s political action

committee had given 67 percent of contributions to Republican candidates. But

October ushered in a sudden change of fortune, according to disclosure reports,

and Democrats received 59 percent of the Pfizer contributions.

Over all, the nation’s top corporations still placed larger bets on Republican

candidates. But at the very time Republicans began to fret publicly about

holding control of Congress, a subtle shift began occurring in contributions to

candidates, particularly in open seats.

“We keep fighting up until the last minute of the last day,” said William C.

Miller, vice president for political affairs at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce,

carefully measuring his words to remain positive about the Republicans’ chances.

“But when the smoke clears on Nov. 8, there are certainly going to be lots of

opportunities for us to get to know the new freshman class.”

An analysis by The New York Times of contributions from Oct. 1 to 18, the latest

data available, shows that donations to Republicans from corporate political

action committees dropped by 11 percentage points in favor of Democratic

candidates, compared with corporate giving from January through September.

Republicans still received 57 percent of contributions, compared with 43 percent

for Democrats, but it was the first double-digit October switch since 1994. “A

lot will hold their powder for now,” said Brian Wolff, deputy executive director

of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. “But after the election, we

will have a lot of new friends.”

Even before the election, many new contributions were funneled toward open

races, like the Eighth Congressional District in Arizona. The Democratic

candidate, Gabrielle Giffords, received checks of $5,000 each from the political

action committees of United Parcel Service and Union Pacific. Lockheed Martin

split the difference, donating $3,000 to Ms. Giffords and sending the same

amount to her Republican rival, Randall Graf.

Until October, Lockheed Martin, the giant military contractor, had been

following its pattern from recent elections of giving about 70 percent of

contributions from its political action committee to Republicans. But Lockheed

Martin’s generosity shifted in the first half of October, with Democrats

receiving 60 percent of donations, or $127,000.

While Republicans and Democrats are feverishly soliciting contributions until

Election Day, campaign finance reports filed this week provide a window into the

final days of a raucous midterm election campaign. The analysis of 288 corporate

political action committees, which have contributed more than $100,000 this

election cycle, found that at least 65 committees had increased their ratio of

contributions to Democrats by at least 15 percentage points, including Sprint,

United Parcel Service and Hewlett-Packard.

A notable exception to the flurry of last-minute giving is Wal-Mart.

“We had a two-year strategy to build up relationships with Democrats,” said Lee

Culpepper, the vice president for federal government relations at Wal-Mart.

“This wasn’t something that we decided in August that we needed to do and we ran

out helter-skelter to try to do it.”

One sign of fresh interest in the prospects of Democratic Congressional races

came one morning this week when more than 100 lobbyists crowded into Democratic

Party headquarters on Capitol Hill. Over Dunkin’ Donuts and coffee, the

executive director of the party’s Congressional committee, Karin Johanson,

delivered a private briefing on the race to a sea of unfamiliar faces, despite

spending 30 years in politics.

“People are excited,” she said later in an interview. “It was, by far, the best

attended one ever.”

As some young Republican lobbyists fled Washington to spend the final days

working on too-close-to-call races in Ohio or Pennsylvania, their senior

counterparts stayed behind to begin studying prospective members of the new

freshman class. Even if Republicans hold control, the next Congress will almost

certainly include at least a handful of moderate Democrats who defeated

Republicans and will be looking for allies in the corporate world.

Peter Welch, the Democratic candidate for Vermont’s single House seat, has

already been telephoning some members of the Washington business lobby, offering

an opportunity to begin a good relationship if he wins election. Never mind that

his Republican opponent, Martha Rainville, has received a host of endorsements

from the business community.

“The real story of the 2006 contributions is what happens in the early phase of

2007, with a change in party control,” said Bernadette A. Budde, senior vice

president of the Business-Industry Political Action Committee. “There will be

proverbial meet-and-greets all over town so we will have a sense of who these

people are.”

Many of these meet-and-greet sessions will have a dual purpose: political action

committees will offer contributions to help candidates wipe away debt their

campaigns accrued during the race.

Spending in the midterm election campaign is forecast to reach $2.6 billion,

according to the Center for Responsive Politics, including $1 billion from

political action committees. While many business groups have been eager to

appear as if they have been handily contributing to Democratic efforts, it was

not until this month that the trend became apparent enough to quantify beyond

party leaders or prospective committee chairmen.

Democrats who are not in tight races — or even standing for re-election in some

cases — have seen their contributions increase more than some of those facing

the most competitive contests. That is an easy way, lobbyists say, for political

action committees to increase the share of their Democratic contributions, a

percentage that is carefully tracked by party leaders when they reach the

majority.

Representative Adam Smith of Washington, who leads a coalition of centrist

Democrats, said he has detected a friendlier relationship with the business

community in recent months, a welcome change from years of Republican rule when

“Democrats were basically frozen out in every way.”

“I hope that the new Democratic majority will take a more open and cooperative

approach,” Mr. Smith said in an interview. “I hope there won’t be a sense of,

‘Oh, you gave too much money to Republicans, so we’re not going to talk to you.’

”

Democrats Get Late Donations From Business, NYT, 28.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/28/us/politics/28hedge.html?hp&ex=1162094400&en=1513adc13f012a0a&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Growth Slackened in Summer

October 28, 2006

The New York Times

By EDUARDO PORTER

Chilled by a summer slowdown in the housing

market, the economy was held to a growth rate of 1.6 percent in the third

quarter, the lowest since early 2003, the government reported yesterday.

But evidence of a decline in inflation coupled with vigorous consumer spending

left most economists saying that the overall economy is unlikely to be dragged

into a recession even as the housing market continues to falter.

“We are in a housing recession, but we are not in a broader economic recession,”

said Richard B. Hoey, chief economist of Mellon Financial.

The government report, which showed growth slowing from a 5.6 percent pace in

the first quarter and 2.6 percent in the second, appeared to validate the

expectation of the Federal Reserve chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, that the economy

is settling softly into a pace consistent with what he considers an acceptably

low level of inflation.

“Ben Bernanke’s forecast was that past Fed tightening would slow demand,” Mr.

Hoey said. “The forecast is tracking as far as I can see.”

Stocks fell and bond prices rose as investors factored in the

weaker-than-expected growth this summer, concluding that the Fed was less likely

to raise interest rates next year.

With the midterm elections little more than a week away, the Bush administration

sought to persuade voters that the economy, while beating at a slower pace,

remains healthy.

“We have a very strong, large resilient economy that can absorb a housing

correction,” said Carlos M. Gutierrez, the commerce secretary. “If you isolate

the impact of the housing correction and look at all the rest, those are solid

numbers.”

But Democrats seized on the report to criticize the administration’s economic

management.

“Economic growth has slowed even before most ordinary Americans have benefited

from this recovery,” Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island, the ranking Democrat on

the Congressional Joint Economic Committee, said in a statement. “It’s clear

that we need a new direction in policy to create an economy that works for all

Americans.”

The economic deceleration in the third quarter was almost single-handedly

brought about by the steep contraction in home building.

Residential investment plummeted 17.4 percent in the quarter, its biggest

decline in more than 15 years. This alone reduced economic growth in the third

quarter by over 1.1 percentage points.

The building of factories, warehouses and commercial structures picked up some

of the slack. Business investment, including structures and machinery, added

nearly 0.9 percentage point to gross domestic product in the quarter.

But what is most remarkable is that the pricking of the housing bubble has

barely spilled over into consumer spending, which is still chugging along. The

government reported that consumer spending grew 3.1 percent in the third quarter

— nearly twice as fast as overall economic growth.

“We have the most reckless and relentless consumers in the world,” said David

Kelly, economic adviser at Putnam Investments in Boston. “It’s wonderful.”

The housing freeze had long been expected to put a chill on consumers’

appetites. Sales of existing homes have declined almost 14 percent over the last

year. The median price of new homes has fallen by almost 10 percent in the last

12 months and existing-home prices have started to decline nationwide.

Many economists assumed that just as consumers had leveraged their buying power

by borrowing against the value of their homes when house prices were rising, now

that house prices are falling they would start saving some money.

That, however, has not happened. Rather, increasing employment and falling gas

prices seem to be providing consumers with new reasons to spend. The personal

savings rate remained negative, at minus 0.5 percent of total disposable income.

The University of Michigan’s index of consumer confidence recorded its

eighth-largest monthly gain in October, vaulting to its highest level since June

2005. Optimism was driven by falling gas prices as well as expectations of

faster economic growth, larger wage gains and low unemployment.

Richard Curtin, who runs the university’s surveys of consumers, noted that

consumers remain reluctant to buy a home, keenly aware of the decline in house

prices. Still, their overall appetite to spend remains as brisk as ever.

Inflation, meanwhile, has started to abate — at least for now. The measure of

inflation preferred by the Fed, which measures the prices of goods and services,

excluding food and energy, that consumers buy, rose 2.3 percent in the third

quarter. This is down from the 2.7 percent rate of the second quarter, bringing

inflation closer to the 1-to-2 percent range Mr. Bernanke considers acceptable.

The growth rate reported by the government is only a preliminary approximation.

Historical experience suggests that subsequent revisions could change it

substantially, for better or worse.

But whatever the ultimate verdict on the summer period, several economists argue

that growth in the fourth quarter is likely to be higher, as consumers spend the

extra money in their wallets from lower gasoline prices on other items.

“So far the quarter is going swimmingly,” said Richard Yamarone, director of

economic research at Argus Research.

The outlook for next year will depend on whether the continuing weakness in the

housing market affects spending.

Orawin Velz, director of economic forecasting at the Mortgage Bankers’

Association, estimated that the fall in residential investment would continue to

drag on the economy through the middle of next year, but that its impact would

decline over time. “We think the third quarter will be the peak of the damage,”

Ms. Velz said.

While many economists foresee a longer period of housing weakness, she said that

supply and demand should come into balance by mid-2007 and that home

construction would start rising next summer.

Still, if the weak housing market starts cutting into consumption, the drag on

overall growth could be more intense.

While it is not yet evident in the official numbers, builders are starting to

shed workers as older projects are completed and there are fewer new ones to

take up the slack. This will probably cut into workers’ income and spending,

slowing growth.

In contrast to many business economists, Dean Baker, co-director of the liberal

Center for Economic Policy and Research in Washington, argued that a consumer

reaction to the weak housing market would pull the economy into a recession next

year.

“Homeowners had been pulling equity out of their homes at more than a $700

billion annual rate,” Mr. Baker wrote yesterday. “This borrowing will slow

sharply in the quarters ahead.”

But others insisted that consumer appetites should not be underestimated.

“Consumer spending hasn’t stopped growing in 59 straight quarters, and some

pretty awful things have happened in those 59 quarters,” Mr. Yamarone said. “We

all keep forgetting that the consumer is resilient.”

Jeremy Peters contributed reporting.

Growth Slackened in Summer, NYT, 28.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/28/business/28econ.html?hp&ex=1162094400&en=fc8b372396bc2cca&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Housing Market a Drag on Economic Growth

October 27, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

Filed at 8:44 a.m. ET

WASHINGTON (AP) --Economic growth slowed to a

crawl in the third quarter, advancing at a pace of just 1.6 percent, the worst

in more than three years.

The latest snapshot of the economy, released by the Commerce Department on

Friday, showed that the slumping housing market figured prominently in the

economy's dramatic loss of momentum. Investment in homebuilding was cut by the

biggest amount since early 1991.

The reading on gross domestic product was weaker than the 2.1 percent pace many

economists were forecasting.

Gross domestic product measures the value of all goods and services produced

within the United States and is considered the best barometer of the country's

economic standing. Friday's report provided the last GDP reading before the Nov.

7 elections.

Economic matters are expected to influence voters' choices when they go to the

polls. President Bush's approval rating on the economy is at 40 percent, among

all adults surveyed in an AP-Ipsos poll. That remains near his lowest ratings.

The people surveyed trusted Democrats more than Republicans to handle the

economy.

The third quarter's 1.6 percent growth rate was the weakest since the first

quarter of 2003, when the economy grew at a 1.2 percent annual rate.

The latest performance underscores just how much speed the economy has lost this

year.

In the opening quarter, the economy grew at a brisk 5.6 percent pace, the

strongest growth spurt in 2 1/2 years. But growth slowed to a 2.6 percent pace

in the second quarter as consumers and businesses tightened the belt in response

to the toll of rising energy prices and the impact of two-plus years of rising

borrowing costs.

In the third quarter, consumers held up well, though. They boosted their

spending at a rate of 3.1 percent, up from a 2.6 percent pace in the second

quarter.

Businesses, meanwhile, increased spending on equipment and software at a 6.4

percent pace in the third quarter, an improvement from the 1.4 percent rate of

decline in the second period.

The economy's softness in the third quarter stemmed in large part from the

cooldown in the once-hot housing market.

Spending on home building dropped at a rate of 17.4 percent in the third

quarter. That was the biggest drop since the first quarter of 1991 when such

spending was sliced at a 21.7 percent pace.

Weak inventory building by businesses and the bloated trade deficit also played

roles in weighing down economic activity in the third quarter.

An inflation gauge tied to the GDP report showed that core prices -- excluding

food and energy -- advanced at a rate of 2.3 percent in the third quarter, which

was down from 2.7 percent in the second quarter.

Over the last 12 months, however, this inflation measure rose by 2.4 percent,

the largest annual increase since 1995.

Energy prices, which had surged in the summer, have since calmed down.

Gas prices are now hovering around $2.23 a gallon nationwide, compared with more

than $3 a gallon in early summer. Oil prices are now just over $61 a barrel,

down from $77.03, a record high close in mid-July.

That is supposed to help ease inflation and lead to better economic activity.

Lower energy prices leave people and companies with more money to spend on other

things. If they spend and invest, that adds to economic growth. Many economists

believe the economy will do better in the current October-to-December quarter,

perhaps clocking in close to 3 percent.

The Federal Reserve held interest rates steady on Wednesday for the third

meeting in a row. The Fed had hoisted rates 17 times since June 2004 to fend off

inflation. The Fed's goal is to slow the economy sufficiently to thwart

inflation but not so much that it tips into recession.

Housing Market a Drag on Economic Growth, NYT, 27.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/business/AP-Economy.html?hp&ex=1162008000&en=637f0f9e820f1a13&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Microsoft Profit and Revenue Up 11% on

Strength of Games and Servers

October 27, 2006

The New York Times

By STEVE LOHR

Microsoft reported solid quarterly results

yesterday that slightly surpassed Wall Street expectations, with sales growth

driven by its Xbox game business and software for server computers. Both revenue

and profit rose 11 percent.

Demand for the company’s software for corporate databases and servers grew

strongly, with sales up 17 percent, to $2.5 billion. Sales of Xbox game

consoles, software and online game subscriptions jumped 70 percent, to more than

$1 billion. Those two businesses accounted for most of Microsoft’s revenue

growth in the quarter, the first in the company’s 2007 fiscal year.

Microsoft’s Internet services business, which competes with Google, Yahoo and

others, continues to struggle. Revenue declined, and the unit lost $136 million.

The twin engines of Microsoft’s personal computer software business — the

Windows operating system and Office productivity programs — grew modestly,

awaiting the introduction of major new versions of both products this quarter.

The Windows and Office business units accounted for 62 percent of Microsoft’s

revenue, and nearly 90 percent of the profit of its operating divisions.

The company announced this week that it would offer free and discounted coupons

for upgrades to the new Windows Vista and Office 2007, for consumers and

businesses that buy personal computers in the holiday season, before Vista and

Office 2007 are available. The effect, Microsoft said, would be to defer revenue

of about $1.5 billion from the current quarter to later in the fiscal year.

“It’s an accounting shift from one quarter to the other, not something that is

economically significant for us over the course of the year,” the chief

financial officer, Christopher P. Liddell, said in an interview.

This fiscal year, which ends in June, Microsoft said it expected to report

revenue of $50 billion to $50.9 billion, and earnings per share of $1.43 to

$1.46.

After Microsoft reported its financial results, its shares rose for a time in

late trading, as high as $28.54. In the regular session, the stock closed at

$28.35, up 4 cents.

“This was a good quarter, and the company gave pretty strong guidance for the

year,” said Charles Di Bona, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Company.

“Microsoft is heading into a strong product cycle, and it looks as if Vista is

going to be a bigger deal than a lot of people expected.

“The longer-term question, though, is around Microsoft’s online services

business. We’re in the midst of this huge online advertising boom, and Microsoft

is going sideways.”

In an interview this month, Steven A. Ballmer, Microsoft’s chief executive,

noted that the MSN and other Web sites gave Microsoft a solid online presence

and that the company had a number of initiatives in place to improve the

performance of that business.

But the quarterly results at the online division underlined the challenge

Microsoft faces. Revenue fell about 5 percent, to $539 million, and the business

swung from a profit of $68 million a year earlier to a loss of $136 million.

Microsoft’s overall revenue for the quarter rose to $10.8 billion, compared with

$9.7 billion in the period a year earlier. Net income increased to $3.48

billion, or 35 cents a share, compared with $3.14 billion, or 29 cents a share,

including a charge of 2 cents a share for legal expenses last year.

The company’s earnings per share were 4 cents higher than the consensus estimate

of analysts compiled by Thomson Financial, and revenue was a bit higher than

expectations.

In a conference call with analysts, Mr. Liddell, the chief financial officer,

said that Microsoft would be looking selectively for acquisitions and that

online services was an industry where Microsoft might make a move, though he did

not elaborate.

The Xbox game console and software unit is an area of investment that seems to

be going according to the company’s plan. The entertainment and devices

division, which includes Xbox, is still losing money but the losses are

shrinking, to $96 million from $173 million a year earlier. The Xbox 360

machines went on sale last year, and six million have been sold worldwide.

Software sales are going well, and Microsoft’s online game service, Xbox Live,

has more than four million members.

That business, Mr. Liddell said, is on track to become profitable in the

2008 fiscal year, which begins next July.

Microsoft Profit and Revenue Up 11% on Strength of Games and Servers, NYT,

27.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/27/technology/27soft.html

New-Home Prices Fall Sharply

October 27, 2006

The New York Times

By JEREMY W. PETERS

Home builders, struggling to keep ahead in a

weakening market, cut prices and offered a variety of other discounts in

September to help sell their newly constructed houses, the latest government and

industry statistics show.

The Commerce Department reported yesterday that the median price of a new home

plunged 9.7 percent last month, compared with September 2005, falling to

$217,100, the biggest such drop since December 1970.

Statistics from the National Association of Home Builders showed a similar

slide. Builders reported cutting prices in September by 5 percent, according to

the association’s most recent data.

Just two months ago, prices of new homes were still on the rise.

At least to some extent, the lower prices achieved the developers’ goal: the

backlog of unsold new homes on the market fell in September for the second

consecutive month, while the number sold, adjusted for normal seasonal

variations, rose by 5.3 percent from the previous month.

But economists and industry experts noted that the reported numbers provide a

somewhat distorted picture of market reality. While they seemed to suggest a

rebound in sales and a precipitous drop in prices, the data was skewed by a

higher number of sales in the South, where homes are cheaper, and fewer in the

more expensive Northeast.

Last month, sales in the South accounted for 56 percent of all new homes sold in

the country, compared with 52 percent a year earlier. The average square footage

of a house sold in September declined as well, pulling down the median price.

While new-home prices across the country may not be falling quite as sharply as

the reported numbers suggest, builders are also offering a variety of hidden

price cuts in response to the much harsher housing climate that they now face.

“We’re going to run our business as if it’s going to stay tough for a while,”

said Richard J. Dugas Jr., chief executive of Pulte Homes, one of the nation’s

largest residential builders. On Wednesday, Pulte said its profit in the third

quarter fell by more than half, compared with the same period a year earlier.

Indeed, profits are falling fast in many parts of the country for builders, who

are rapidly scaling back on their future construction plans.

The home builders’ association reported that 45 percent of builders and

developers said they cut prices in September to maintain sales volume. That was

up from only 19 percent a year earlier. Similarly, the association reported that

55 percent offered amenities like granite counters or upgraded kitchen cabinets

for no additional cost. Only 19 percent did so a year earlier.

The cost of those incentives was not reflected in the new-home price data, which

suggested that builders were making even less money from each sale than the

shrinking official prices would indicate.

“Builders do not like to lower prices because it sends the wrong signal to

potential buyers,” Patrick Newport, an economist with Global Insight, said in a

research note. “How much incentives matter today is difficult to gauge — but in

markets in which power is quickly shifting from sellers to buyers, they probably

matter quite a bit.”

Cancellations were also left out of the new-home statistics. The Commerce

Department records a new home as sold when the buyer and builder sign a

contract. The home builders association said that cancellations had jumped by 50

percent in the last year.

“The cancellation rate is really big,” said Dave Seiders, chief economist of the

association. “It’s exploded over the last year.”

The new-home sales report followed a report that showed softness in the market

for previously owned homes, which account for about 85 percent of all home

sales.

The pace of existing-home sales in September slowed 14 percent from a year

earlier to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 6.2 million. That was the lowest

rate reported since January 2004.

For new homes, the seasonally adjusted annual sales volume figure in September

was 1.1 million — 14.2 percent lower than in September 2005.

Another closely watched economic barometer released this morning — the Census

Bureau’s report on durable goods orders — showed an unexpected 7.8 percent rise

for September from August. Durable goods, which include things like dishwashers,

are monitored by economists as a gauge of business investment.

The upswing, however, was almost entirely a result of a surge in orders for

aircraft. Boeing took orders for 175 planes last month, nearly tripling the

nonmilitary aircraft component of the durable goods figure.

Over all, the latest economic data pointed to continued but slower growth

through the end of the summer. When orders for the transportation equipment

sector were stripped out, the gain in durable goods orders was only 0.1 percent.

New-Home Prices Fall Sharply, NYT, 27.10.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/27/business/27econ.html

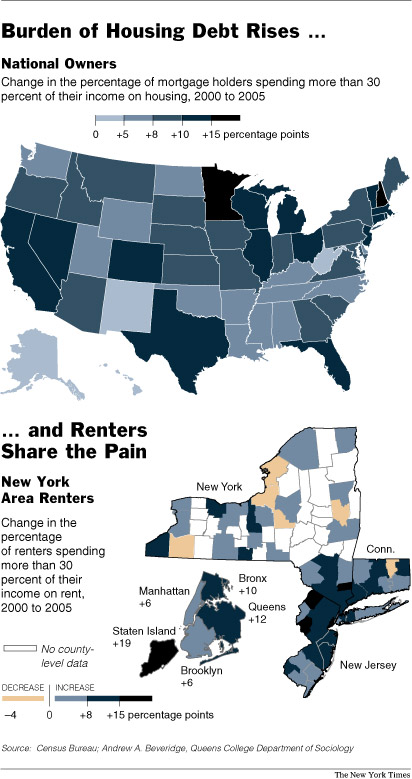

Rent’s Bite Is Big in Kansas, Too

October 23, 2006

The New York Times

By SUSAN SAULNY

OLATHE, Kan. — New census data shows that

people are paying more of their income for housing in almost every part of the

country. And it is hardly surprising that places like Southern California and

Manhattan are high on the list.

But Olathe? In northeast Kansas?

Olathe (pronounced oh-LAY-thuh), 20 miles southwest of Kansas City, showed the

biggest jump in the percentage of people paying at least 30 percent of their

income on rent, as well as in those paying at least 50 percent on rent.

In a largely rural state not known for growth or overwhelming prosperity, here

is a minimetropolis of manmade neighborhood waterfalls, of seemingly endless

construction of shopping malls and office parks. Executives and immigrant

workers, retirees and young families have all been drawn to its abundance of

jobs, parks and high-performing public schools.

“It’s basically been a supernova in terms of its growth,” said Arthur P. Hall,

the executive director of the Center for Applied Economics at the University of

Kansas School of Business. “It’s a major suburb of Kansas City and for whatever

reason has become the place to go. And that I can’t explain.”

Ever since Olathe’s days as a stagecoach stop on the old Santa Fe Trail there

have been newcomers at the crossroads here, usually to take a rest and to move

on. But as this prairie town and former bedroom community of close to 120,000

looks back to celebrate its 150th birthday, it is clear what has changed: people

come to stay. And they pay a lot to do it.

“We grow 10 people a day, every single day,” Mayor Michael Copeland boasts, and

population statistics back him up: Olathe has expanded by about 4,000 people a

year for the past several years.

Since 1980, the population has more than tripled. And in the last five years,

the average price for a new home has doubled to about $350,000.

The census data was collected before the real estate market began softening over

the last year, and it was based on a small sample size, experts cautioned. And

at the high economic end, Olathe is dominated by homeowners who can afford their

properties without mortgages, in one of the most prosperous counties in the

country.