|

History > 2006 > USA > Terrorism (III)

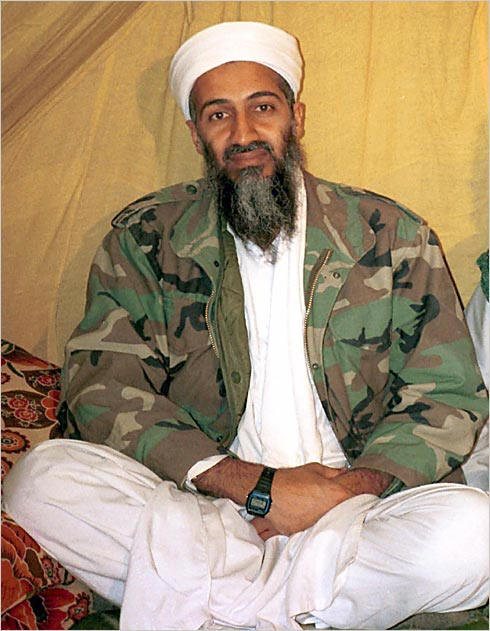

Hopes of cornering

Osama bin Laden, the Saudi-born al-Qaeda leader, seem

distant as ever.

Undated AP photo

Bin Laden manhunt still drawing a blank

UT 1.9.2006

http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2006-09-01-bin-laden-hunt_x.htm

Al - Zawahri:

Bush a Liar in War on Terror

September 30, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 3:30 a.m. ET

The New York Times

CAIRO, Egypt (AP) -- Al-Qaida No. 2 Ayman

al-Zawahri called President Bush a failure and a liar in the war on terror in a

video statement released Friday, and he compared Pope Benedict XVI to the 11th

century pontiff who launched the First Crusade.

''Can't you be honest at least once in your life, and admit that you are a

deceitful liar who intentionally deceived your nation when you drove them to war

in Iraq?'' Osama bin Laden's deputy said, appearing in front of a standing lamp

and a small, decorative cannon.

Al-Zawahri also criticized Bush for continuing to imprison al-Qaida leaders in

prisons, including al-Qaida No. 3 Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged Sept. 11

mastermind who was captured in Pakistan in March 2003.

''Bush, you deceitful charlatan, 3 1/2 years have passed since your capture of

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, so how have you found us during this time? Losing and

surrendering? Or are we launching attacks with God's help and becoming

martyrs?'' he said.

''What you have perpetrated against Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other Muslim

captives in your prisons and the prisons of your slaves in Egypt, Jordan,

Pakistan and elsewhere is not hidden from anyone, and we are a people who do not

sleep under oppression and who do not abandon our revenge until our chests have

been healed of those who have committed aggression against us,'' he said.

''And we, by the grace of Allah, are seeking to exact revenge on behalf of Islam

and Muslims from you and your soldiers and allies.''

Al-Zawahri accused the United States and its agents of torturing Muslim

prisoners seized across the Middle East.

''Your agents in the Arabian Peninsula, Yemen, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Pakistan and

Afghanistan have captured thousands of the youth and soldiers of Islam whom you

made to taste at your hands and the hands of your agents various types of

punishment and torture,'' al-Zawahri said.

Ben Venzke, head of the Virginia-based IntelCenter, which monitors terrorism

communications, said al-Zawahri essentially gave al-Qaida's spin on the arrests

and detentions of its leaders.

''They are countering arguments that individuals have been able to provide

useful information,'' he said. ''And they are continuing to reinforce their

intentions for revenge.''

Al-Zawahri said Benedict is reminiscent of Pope Urban II, who in 1095 ordered

the First Crusade to establish Christian control in the Holy Land.

''This charlatan Benedict brings back to our memories the speech of his

predecessor charlatan Urban II in the 11th century ... in which he instigated

Europeans to fight Muslims and launch the Crusades because he (Urban) claimed

'atheist Muslims, the enemies of Christ' are attacking the tomb of Jesus Christ,

peace be upon him,'' al-Zawahri said.

Al-Zawahri's remarks about Benedict were a clear response to the pontiff's

comments this month that sparked outrage across the Muslim world. In that

speech, Benedict cited a Byzantine emperor who characterized some of the

teachings of the Prophet Muhammad as ''evil and inhuman,'' particularly ''his

command to spread by the sword the faith.''

''If Benedict attacked us, we will respond to his insults with good things. We

will call upon him and all of the Christians to become Muslims who do not

recognize the Trinity or the crucifixion,'' al-Zawahri said.

Al-Zawahri also called a U.N. resolution to send peacekeepers into Sudan's

war-torn Darfur region a ''Crusader plan'' and implored the Muslims of Darfur to

defend themselves.

''There is a Crusader plan to send Crusaders forces to Darfur that is about to

become a new field of the Crusades war. Oh, nation of Islam, rise up to defend

your land from the Crusaders aggression who are coming wearing United Nations

masks,'' he said. ''No one will defend you (Darfur) but a popular holy war.''

The nearly 18-minute statement, titled ''Bush, the Pope, Darfur and the

Crusades,'' was produced by al-Qaida's media arm, as-Sahab, and made available

by the IntelCenter. An initial segment shows al-Zawahri in an office-type

setting, while in the second part he is in front of a brown backdrop. The first

segment also has English subtitles.

After conducting a technical analysis of the videotape, the CIA concluded ''with

confidence'' that the speaker is in fact Ayman al-Zawahri, said a CIA

spokesperson who spoke on condition of anonymity

An intelligence official, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said U.S.

experts view the latest video as a typical propaganda message, whose main thrust

is a call for more people to join the jihad, or holy war.

It wasn't immediately clear when the message was recorded, the official said,

but al-Zawahri's reference to the pope indicated the message was produced

sometime after Benedict's Sept. 12 comments about Islam.

Al-Qaida has released a string of videos to coincide with the fifth anniversary

of the Sept. 11 attacks, showing increasingly sophisticated production

techniques in a likely effort to demonstrate that it remains a powerful,

confident force despite the U.S.-led war on terror.

The IntelCenter said Friday's video was the 48th released by the al-Qaida Web

site this year, three times more than last year's number -- which had been the

highest. It said al-Zawahri has appeared in 14 of the 2006 videos.

Al -

Zawahri: Bush a Liar in War on Terror, NYT, 30.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/world/AP-Al-Qaida-Tape.html

Growing Unarmed Battalion in Qaeda Army Is

Using Internet to Get the Message Out

September 30, 2006

The New York Times

By HASSAN M. FATTAH

AMMAN, Jordan — On the fifth anniversary of

the Sept. 11 attacks, Abu Omar received the call to jihad. Literally.

“There’s a present for you,” a voice on the other end of the phone said that

morning, he recalled. It was a common code whenever his friends and colleagues

wanted to share a new broadcast or communiqué from Al Qaeda over the Internet,

he said.

Abu Omar, speaking on the condition that only his nickname be used, said he soon

went to one of the Internet cafes he frequents in Amman and began distributing

the latest video by Al Qaeda, alerting friends and occasionally adding

commentary.

“We are the energy behind the path to jihad,” Abu Omar said proudly. “Just like

the jihadis reached their target on Sept. 11, we will reach ours through the

Internet.”

Abu Omar, 28, is part of an increasingly sophisticated network of contributors

and discussion leaders helping to wage Al Qaeda’s battle for Muslim hearts and

minds. A self-described Qaeda sympathizer who defends the Sept. 11 attacks and

continues to find inspiration in Osama bin Laden’s call for jihad, Abu Omar is

part of a growing army of young men who may not seek to take violent action, but

who help spread jihadist philosophy, shape its message and hope to inspire

others to their cause.

Though he does not appear to be directly connected to Al Qaeda, Abu Omar does

seem to be on a direct e-mail list for groups sympathetic to Al Qaeda, making

him a link in a chain that spreads the organization’s propaganda using code and

special software to circumvent official scrutiny of their Internet activity.

As Al Qaeda gradually transforms itself from a terrorist organization carrying

out its own attacks into an ideological umbrella that encourages local movements

to take action, its increased reliance on various forms of media have made

Web-savvy sympathizers like Abu Omar ever more important.

For example, this past Sept. 11, Abu Omar said, a link sent to a jihadist e-mail

list took him to a general interest Islamic Web site, which led him to a

password-protected Web site, then onto yet another site containing the latest

release from Al Qaeda: a lecture by its No. 2 man, Ayman al-Zawahri, threatening

attacks on Israel and the Persian Gulf. Abu Omar said he then passed the video

to friends and confidants, acting as a local distributor to other sympathizers.

In recent years, Al Qaeda has formed a special media production division called

Al Sahab to produce videos about leaders like Mr. bin Laden and Mr. Zawahri,

terrorism experts say. The group largely once relied on Arab television channels

like Al Jazeera to broadcast its videos and taped messages.

Al Sahab, whose name means the cloud, has continued to draw on a video library

featuring everything from taped suicide messages by the Sept. 11 hijackers to

images of gun battles and bombings spearheaded by Al Qaeda and others, said

Marwan Shehadeh, an expert on Islamist movements with the Vision Research

Institute in Amman who has close ties to jihadists in Jordan and Syria.

But this year Al Sahab has released many more recordings than in previous years,

said Chris Heffelfinger, a specialist in jihadi ideology at the Combating

Terrorism Center at West Point, in what many analysts see as a new offensive

focusing on the Muslim mainstream. Jihadi Web sites, meanwhile, have continued

sprouting on the Internet, serving as a conduit for Al Qaeda’s propaganda.

Mr. Shehadeh describes Al Sahab as an informal group with video camcorders and

laptops. Some news reports have described it as an organization with a mobile

production unit that navigates the Pakistani provinces. “The jihadis have

successfully used American technology to show the U.S. as a loser,” Mr. Shehadeh

said. “This is an open-ended war, and they use media as part of their jihad

against Western and Arab regimes.”

Just days before the fifth anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, Al Sahab

released a barrage of videos, including images of Mr. bin Laden seated with some

of the Sept. 11 suicide bombers; a documentary that some have described as a

“making of Sept. 11” feature, with testaments by two of the bombers; and the

lecture by Mr. Zawahri that Abu Omar said he received that morning.

What is most striking about the messages is their tone, terrorism analysts say.

In the past, the group’s leaders were generally depicted as soldiers in battle,

often filmed outdoors with weapons in the background. But the more recent

communiqués show Al Qaeda’s leaders in the comfort of a living room or office,

set against bookshelves with religious texts. The group has also taken to

quoting Western authors and famous speeches, in what seems to be an effort to

reach those with Western sensibilities.

“It’s a clear message: when there’s a gun in the background, they’re saying,

‘I’m a fighter like you’; when there are books in the background, it means, ‘I

am a scholar and deserve authority,’ ” said Fares bin Hizam, a journalist who

reports on militant groups for the Arab satellite news channel Al Arabiya. “It

is a message that resonates well with an impressionable young man who is 17 or

18.”

One result, terrorism analysts say, is a militant group in transition, seeking

to push ideology over direct action, franchising its name and principles to

smaller groups acting more independently.

“Al Qaeda has been turning itself from an active organization into a propaganda

organization,” said Mr. Heffelfinger. “They now appear to be focused on putting

out disinformation and projecting the strength of the mujahedeen. They’re no

longer the group that is organizing the mujahedeen. Instead, they are giving

guidance to all the movements.”

Men like Abu Omar have become integral to that transformation. Mr. Shehadeh, who

introduced Abu Omar to this reporter, says he has known Abu Omar ever since he

was a teenager and has observed his gradual embrace of jihadist ideology. He

says he has seen Abu Omar’s contributions on numerous chat boards and notes that

while Abu Omar is probably not a Qaeda member, he regularly relays news and

spreads the group’s message to friends and colleagues.

In Amman’s more conservative neighborhoods, Abu Omar and several analysts said,

one or two jihadists tend to be the organizers, distributing messages and

content to volunteers, and controlling membership in jihadist e-mail lists.

“We are typically observers, but when we see something on the Net, our job is to

share it,” Abu Omar said. He no longer trusts news reports on television, he

said. He even cast doubt on Al Jazeera, which typically broadcasts Al Qaeda’s

videos but is, he said, still beholden to Arab governments. “We become like

journalists ourselves.”

Abu Omar, who owns a computer store in one of Amman’s refugee camps, said he

became involved in jihadi movements about six years ago, driven in part by his

anger over the death of his father, who he said was a fighter with the

Palestinian faction Fatah when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982. “On the Net, you

can see all the pictures of Palestine and the Muslim world being attacked, and

then you see the planes crashing into one of the towers and you think, ‘I can

understand it,’ ” he said.

He goes to an Internet cafe several times a week. In recent years, Jordan’s

Internet cafes have begun taking increased security measures, like registering

users’ identification cards, he said, but jihadists in Amman alternate among a

network of sympathetic cafe owners who allow them to surf anonymously.

He never uses his own computer to search for jihadi content, and he limits his

time online to about 30 minutes — not long enough for the authorities to locate

him, he figures.

In 2005, Jordanian authorities arrested an 18-year-old man, Murad al-Assaydeh,

accusing him of using the Internet to threaten attacks on intelligence

officials. Abu Omar said several of his friends and comrades had been arrested

by the General Information Department in Jordan in connection with Mr.

Assaydeh’s case and in subsequent dragnets. Abu Omar said he was once called in

for questioning but was released the same day.

He now changes his e-mail address frequently, he said, and he typically carries

software that can delete details of his actions from a computer. “In the

beginning, I thought maybe I would go for jihad in Iraq, but it was very

difficult to get there,” he said. “Now I realize it’s better to work on the Net

and get the message out.”

Growing Unarmed Battalion in Qaeda Army Is Using Internet to Get the Message

Out, NYT, 30.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/30/world/30jordan.html?hp&ex=1159675200&en=56cc8b833e65ab51&ei=5094&partner=homepage

News Analysis

Detainee Bill Shifts Power to President

September 30, 2006

The New York Times

By SCOTT SHANE and ADAM LIPTAK

WASHINGTON, Sept. 29 — With the final passage

through Congress of the detainee treatment bill, President Bush on Friday

achieved a signal victory, shoring up with legislation his determined conduct of

the campaign against terrorism in the face of challenges from critics and the

courts.

Rather than reining in the formidable presidential powers Mr. Bush and Vice

President Dick Cheney have asserted since Sept. 11, 2001, the law gives some of

those powers a solid statutory foundation. In effect it allows the president to

identify enemies, imprison them indefinitely and interrogate them — albeit with

a ban on the harshest treatment — beyond the reach of the full court reviews

traditionally afforded criminal defendants and ordinary prisoners.

Taken as a whole, the law will give the president more power over terrorism

suspects than he had before the Supreme Court decision this summer in Hamdan v.

Rumsfeld that undercut more than four years of White House policy. It does,

however, grant detainees brought before military commissions limited protections

initially opposed by the White House. The bill, which cleared a final procedural

hurdle in the House on Friday and is likely to be signed into law next week by

Mr. Bush, does not just allow the president to determine the meaning and

application of the Geneva Conventions; it also strips the courts of jurisdiction

to hear challenges to his interpretation.

And it broadens the definition of “unlawful enemy combatant” to include not only

those who fight the United States but also those who have “purposefully and

materially supported hostilities against the United States.” The latter group

could include those accused of providing financial or other indirect support to

terrorists, human rights groups say. The designation can be made by any

“competent tribunal” created by the president or secretary of defense.

In very specific ways, the bill is a rejoinder to the Hamdan ruling, in which

several justices said the absence of Congressional authorization was a central

flaw in the administration’s approach. The new bill solves that problem, legal

experts said.

“The president should feel he has better authority and direction now,” said

Douglas W. Kmiec, a conservative legal scholar at the Pepperdine University

School of Law. “I think he can reasonably be confident that this statute answers

the Supreme Court and puts him back in a position to prevent another attack,

which is the goal of interrogation.”

But lawsuits challenging the bill are inevitable, and critics say substantial

parts of it may well be rejected by the Supreme Court.

Over all, the legislation reallocates power among the three branches of

government, taking authority away from the judiciary and handing it to the

president.

Bruce Ackerman, a critic of the administration and a professor of law and

political science at Yale University, sharply criticized the bill but agreed

that it strengthened the White House position. “The president walked away with a

lot more than most people thought,” Mr. Ackerman said. He said the bill “further

entrenches presidential power” and allows the administration to declare even an

American citizen an unlawful combatant subject to indefinite detention.

“And it’s not only about these prisoners,” Mr. Ackerman said. “If Congress can

strip courts of jurisdiction over cases because it fears their outcome, judicial

independence is threatened.”

Even if the Supreme Court decides it has the power to hear challenges to the

bill, the Bush administration has gained a crucial advantage. In adding a

Congressional imprimatur to a comprehensive set of procedures and tactics,

lawmakers explicitly endorsed measures that in other eras were achieved by

executive fiat. Earlier Supreme Court decisions have suggested that the

president and Congress acting together in the national security arena can be an

all-but-unstoppable force.

Public commentary on the bill, called the Military Commissions Act of 2006, has

been fast-shifting and often contradictory, partly because its 96 pages cover so

much ground and because the impact of some provisions is open to debate.

“This bill is about so many things, and it’s a mixed bag,” said Elisa Massimino,

the Washington director of Human Rights First, a civil liberties group.

Ms. Massimino’s group and others criticized the bill as a whole, but she agreed

with the Republican senators who negotiated for weeks with the White House that

it would ban the most extreme interrogation methods used by the Central

Intelligence Agency and the military.

“The senators made clear that waterboarding is criminal,” Ms. Massimino said,

referring to a technique used to simulate drowning. “That’s a human rights

enforcement upside.”

The debate over the limits of torture and the rules for military commission

dominated discussion of the bill until this week. Only in the last few days has

broad attention turned to its redefinition of “unlawful enemy combatant” and its

ban on habeas corpus petitions, which suspects have traditionally used to

challenge their incarceration.

Law professors will stay busy for months debating the implications. The most

outspoken critics have likened the law’s sweeping provisions to dark chapters in

history, comparable to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in the fragile

years after the nation’s founding and the internment of Japanese-Americans in

the midst of World War II.

Conservative legal experts, by contrast, said critics could no longer say the

Bush administration was guilty of unilateral executive overreaching.

Congressional approval can cure many ills, Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote in

his seminal concurrence in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company v. Sawyer, the 1952

case that struck down President Harry S. Truman’s unilateral seizure of the

nation’s steel mills during the Korean War.

Supporters of the law, in fact, say its critics will never be satisfied. “For

years they’ve been saying that we don’t like Bush doing things unilaterally,

that we don’t like Bush doing things piecemeal,” said David B. Rivkin, a Justice

Department official in the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H. W.

Bush.

How the measure will look decades hence may depend not just on how it is used

but on how the terrorist threat evolves. If a major terrorist plot in the United

States is uncovered — and surely if one succeeds — it may vindicate the

Congressional decision to give the government more leeway to seize and question

those who might know about the next attack.

If the attacks of 2001 recede as a devastating but unique tragedy, the decision

to create a new legal framework may seem like overkill. “If there is never

another terrorist attack and we never obtain actionable intelligence, this will

look like a huge overreaction,” said Gary J. Bass, a professor of politics and

international affairs at Princeton.

Long before that judgment arrives, legal challenges are likely to bring the new

law before the Supreme Court. Assuming the justices rule that they retain the

power to hear the case at all, they will then decide whether Congress has

resolved the flaws it found in June or must make another effort to balance the

rights of accused terrorists and the desire for security.

Detainee Bill Shifts Power to President, NYT, 30.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/30/us/30detain.html?hp&ex=1159675200&en=4b0651b4401c1962&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Lawyer in Terror Case Apologizes for

Violating Special Prison Rules

September 29, 2006

The New York Times

By JULIA PRESTON

Lynne F. Stewart, the once brashly defiant

radical defense lawyer who was convicted in a federal terrorism trial last year,

has acknowledged in a personal letter to the court that she knowingly violated

prison rules and was careless, overemotional and politically naïve in her

representation of a terrorist client.

After a trial of more than seven months, Ms. Stewart was convicted in February

2005 of providing aid to terrorism. Her sentencing has been repeatedly postponed

because of her treatments for breast cancer, which she first discovered last

November.

Ms. Stewart sent the letter on Tuesday to the judge in the case, John G. Koeltl

of Federal District Court in Manhattan, appealing to him for leniency when he

decides her sentence. The sentencing is now set for Oct. 16, and prosecutors,

citing “a pattern of purposeful and willful” criminal conduct, have asked for a

prison term of 30 years. Lawyers for Ms. Stewart, who is 66, have asked the

judge to spare her any prison time.

The somber letter is the first time since she was convicted that Ms. Stewart has

addressed herself directly to the judge to explain her actions, rather than

allowing her lawyers to speak for her.

Her argument is strikingly different from her testimony during the trial, when

she admitted no wrongdoing and confidently defended her provocative legal

strategies in her defense of Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman, a fundamentalist Islamic

cleric from Egypt who is serving a life sentence for a thwarted 1993 plot to

bomb New York landmarks.

Now Ms. Stewart admits that she intentionally broke strict rules that barred the

sheik from communicating with his followers outside the prison, when she

conveyed messages from him to the press in June 2000. But she insists that she

“tested the limits” of the law only as a zealous lawyer, and never intended to

help the sheik’s terrorist followers, whose goals she did not share.

Subdued and regretful, Ms. Stewart acknowledges that her legal approach in

defending the sheik and herself was misguided and out of touch with the growing

fear of terrorism in the country even before the Sept. 11 attacks, and certainly

after them.

“I violated my SAM’s affirmation,” Ms. Stewart wrote, referring to her signed

agreement to uphold the prison’s special administrative measures imposed on Mr.

Abdel Rahman. “I permitted him to communicate publicly and these statements if

misused may have allowed others to further their goals.” But she added, “These

goals were not mine.”

“My only motive,” she wrote, “was to serve my client as his lawyer. What might

have been legitimately tolerated in 2000-2001, was after 9/11 interpreted

differently and considered criminal. At the time I didn’t see this. I see and

understand it now.”

Ms. Stewart says that she committed lapses of judgment, and “I was also naïve in

the sense that I was overly optimistic about what I could and should accomplish

as the sheik’s lawyer, and I was careless.” She failed to understand, she said,

that in representing a convicted terrorist, “a lawyer might need to tread

lightly on this ground.” And she underestimated how prosecutors would react to

her pushing the edges of the law.

“I was blind,” she wrote, to the fact that the government “could misunderstand

and misinterpret my true purpose, which was to advocate for my client.”

She was busy defending criminal clients in that period, she wrote, and “I became

spread too thinly,” and “failed to give sufficient attention to the possible

repercussions or the gravity of my actions in how I represented” the sheik. She

calculated that the worst that could happen would be a ban on visits to her

client.

Ms. Stewart insisted that she did not support any violent Islamic cause. “Those

who know me best, as a mother, a family member and a lawyer, know that I am not

a terrorist,” she wrote.

In Aug. 30 sentencing papers, the prosecutors, led by an assistant United States

attorney, Andrew S. Dember, rejected Ms. Stewart’s arguments that she was within

the bounds of a zealous defense of her client.

“What Stewart and her supporters fail to recognize and acknowledge is the

seriousness of Stewart’s criminal conduct, the severity of the potential

consequences of her providing material support to a terrorist organization, and

the fact that her criminal conduct simply had nothing to do with zealous legal

representation,” the prosecutors argued. “Stewart did not walk a fine line of

zealous advocacy and accidentally fall over it; she marched across it into a

criminal conspiracy.”

Ms. Stewart’s lawyers, led by Joshua L. Dratel, have filed motions to compel the

government to disclose whether the National Security Agency recorded her or her

lawyers by wiretapping without warrants.

Lawyer in Terror Case Apologizes for Violating Special Prison Rules, NYT,

29.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/29/nyregion/29stewart.html

Trampling Rights to Fight Terrorism (6

Letters)

September 29, 2006

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Rushing Off a Cliff” (editorial, Sept. 28):

You say that the broad definition of “illegal enemy combatant” in the

antiterrorism bill railroaded through Congress could subject legal residents of

the United States “to summary arrest and indefinite detention with no hope of

appeal” and that “the president could give the power to apply this label to

anyone he wanted.”

Detainees would lose the basic right to challenge their imprisonment, and anyone

could be locked up forever, with no reason given and no notification to friends

and family.

Many of us are bitterly opposed to the current administration and have angered

those who support the disaster in Iraq. What is to prevent letters, lies and

innuendoes from being sent to the authorities accusing us of being illegal enemy

combatants and a danger to the country?

What redress would we have? I tell myself that this could never happen here, but

I fear we are on a very slippery slope.

Mabel J. Dudeney

Norwalk, Conn., Sept. 28, 2006

To the Editor:

Terrorism poses a grave and different kind of threat to the Republic. Yet it is

no more grave than, say, Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union.

No one has explained how it is different in ways that justify condoning torture,

rewriting international law, discarding principles of due process and human

decency, ceding judicial authority to the president, and putting our troops and

reputation in further jeopardy.

The president’s pre-election antiterrorism legislation will do these things. It

is a measure of cravenness that members of both parties would vote for this bill

for political expediency.

Christopher J. Mugel

Richmond, Va., Sept. 28, 2006

To the Editor:

“Rushing Off a Cliff” is off the mark. I say that those who try to tear down our

rights do not deserve to have their rights protected by us.

But you say otherwise — that we must use judicious restraint and care to fight

an enemy who is willing to fight without restraint and to win at all cost.

I don’t think we can win fighting that way. In trying to vigorously protect our

enemy’s rights, we will surely lose ours.

Bill Decker

San Diego, Sept. 28, 2006

To the Editor:

We have reached the point where we must demand that the president uphold the

Constitution.

In the past, when a politician rose to the highest office in the land, it was

taken for granted that he would put the nation first. Unfortunately, this is no

longer the case.

Unless we act and demand that our elected representatives act in our behalf, we

will have an executive with unlimited power.

Bob Geary

Portland, Ore., Sept. 28, 2006

To the Editor:

The day the detainee bill is signed will be a day that will live in dishonor in

our history. The practices that appalled us in the past when used by sleazy

regimes will be incorporated into our legal heritage.

If we do not reject the responsible party in power, we will indict ourselves as

accomplices before decent world opinion.

(Rev.) Connell J. Maguire

Riviera Beach, Fla., Sept. 28, 2006

The writer is a retired Navy captain.

To the Editor:

You say that the “Bush administration uses Republicans’ fear of losing their

majority to push through ghastly ideas about antiterrorism that will make

American troops less safe and do lasting damage to our 217-year-old nation of

laws.” This is correct, but incomplete.

This administration seeks to strike fear in the hearts of all Americans so it

can maintain total control. It uses the issue of security to create insecurity,

while Democrats remain silent.

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt said that “the only thing we have to fear is fear

itself.” The contrast is striking with today, when we seem to fear everything

and reward the political opportunists who thrive on it.

Morris Roth

Fort Lee, N.J., Sept. 28, 2006

Trampling Rights to Fight Terrorism (6 Letters), NYT, 29.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/29/opinion/l29detain.html

Senate Passes Broad New Detainee Rules

September 29, 2006

The New York Times

By KATE ZERNIKE

WASHINGTON, Sept. 28 — The Senate approved a

measure on Thursday on the interrogations and trials of terrorism suspects,

establishing far-reaching rules to deal with what President Bush has called the

most dangerous combatants in a different type of war.

The vote was 65 to 34. It was cast after more than 10 hours of often impassioned

debate that touched on the Constitution, the horrors of Sept. 11 and the role of

the United States in the world.

Both parties also positioned themselves for the continuing clash over national

security going into the homestretch of the midterm elections. The vote showed

that Democrats believe that President Bush’s power to wield national security as

a political issue is seriously diminished. [News analysis, Page A20.]

The bill would set up rules for the military commissions that will allow the

government to proceed with the prosecutions of high-level detainees including

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, considered the mastermind of the Sept. 11, 2001,

attacks.

It would make illegal several broadly defined abuses of detainees, while leaving

it to the president to establish specific permissible interrogation techniques.

And it would strip detainees of a habeas corpus right to challenge their

detentions in court.

The bill is the same as one that the House passed, eliminating the need for a

conference between the two chambers. The House is expected to approve the Senate

bill Friday, sending it to the president to be signed.

The bill was a compromise between the White House and three Republican senators

who had resisted what they saw as Mr. Bush’s effort to rewrite the nation’s

obligations under the Geneva Conventions. Although the president had to relent

on some major provisions, the vote allows him to claim victory in achieving a

main legislative priority.

“As our troops risk their lives to fight terrorism, this bill will ensure they

are prepared to defeat today’s enemies and address tomorrow’s threats,” the

president said in a statement after the vote.

Republicans argued that the new rules would provide the necessary tools to fight

a new kind of enemy.

“Our prior concept of war has been completely altered, as we learned so

tragically on Sept. 11, 2001,” Senator Saxby Chambliss, Republican of Georgia,

said. “And we must address threats in a different way.”

Democrats argued that the rules were being rushed through for political gain too

close to a major election and that they would fundamentally threaten the

foundations of the American legal system and come back to haunt lawmakers as one

of the greatest mistakes in history.

“I believe there can be no mercy for those who perpetrated the crimes of 9/11,”

Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, Democrat of New York, said. “But in the process

of accomplishing what I believe is essential for our security, we must hold onto

our values and set an example that we can point to with pride, not shame.”

Twelve Democrats crossed party lines to vote for the bill. One Republican,

Senator Lincoln Chafee of Rhode Island, voted against it.

But provisions of the bill came under criticism from Republicans as well as

Democrats, with several crossing lines on amendments that failed along narrow

margins.

Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, the senior Democrat on the Armed Services

Committee, arguing for an amendment to strike a provision to bar suspects from

challenging their detentions in court, said it “is as legally abusive of the

rights guaranteed in the Constitution as the actions at Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo

and secret prisons were physically abusive of detainees.”

The amendment failed, 51 to 49.

Even some Republicans who voted for the bill said they expected the Supreme

Court to strike down the legislation because of the provision barring court

detainees’ challenges, an outcome that would send the legislation right back to

Congress.

“We should have done it right, because we’re going to have to do it again,” said

Senator Gordon H. Smith, Republican of Oregon, who voted to strike the provision

and yet supported the bill.

The measure would broaden the definition of enemy combatants beyond the

traditional definition used in wartime, to include noncitizens living legally in

the United States as well as those in foreign countries and anyone determined to

be an enemy combatant under criteria defined by the president or secretary of

defense.

It would strip at Guantánamo detainees of the habeas right to challenge their

detention in court, relying instead on procedures known as combatant status

review trials. Those trials have looser rules of evidence than the courts.

It would allow of evidence seized in this country or abroad without a search

warrant to be admitted in trials.

The bill would also bar the admission of evidence obtained by cruel and inhuman

treatment, except any obtained before Dec. 30, 2005, when Congress enacted the

Detainee Treatment Act, that a judge declares reliable and probative.

Democrats said the date was conveniently set after the worst abuses at Abu

Ghraib and Guantánamo.

The legislation establishes several “grave breaches” of Common Article 3 of the

Geneva Convention that are felonies under the War Crimes Act, including torture,

rape, murder and any act intended to cause “serious” physical or mental pain or

suffering.

The issue was sent to Congress as a result of a Supreme Court decision in June

that struck down military tribunals that the Bush administration had established

shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. The court ruled that the tribunals violated

the Constitution and international law.

The White House submitted a bill this month to authorize a tribunal system,

setting off intraparty fighting as the three Senate Republicans, Lindsey Graham

of South Carolina, John McCain of Arizona and John W. Warner Jr. of Virginia,

insisted that they would not support a provision that in any way appeared to

alter the commitments under the Geneva Conventions.

Such a redefinition, they argued, would send a signal to other nations that

they, too, could rewrite their commitments to the 57-year-old conventions and,

ultimately, lead to Americans seized in wartime being abused and tried in

kangaroo courts.

The White House and the senators came to their agreement last week.

Democrats and human rights groups objected to changes in the legislation over

the weekend, as the House and White House drafted final language, including

defining enemy combatants and setting rules on search warrants.

“We should get this right, now, and we are not doing so by passing this bill,”

Senator Harry Reid, the Nevada Democrat who is the minority leader, said before

the vote. “Future generations will view passage of this bill as a grave error.”

Human rights groups called the vote to approve the bill “dangerous” and

“disappointing.” Critics feared that it left the president a large loophole by

allowing him to set specific interrogation techniques.

Senators Graham, McCain and Warner rebutted that vociferously, arguing in floor

statements, as well as in a colloquy submitted into the official record, that

the measure would in no way give the president the authority to authorize any

interrogation tactics that do not comply with the Detainee Treatment Act and the

Geneva Conventions, which bar cruel and inhuman treatment, and that the bill

would not alter American obligations under the Geneva Conventions.

“The conventions are preserved intact,” Mr. McCain promised his colleagues from

the floor.

After the vote, Mr. Graham said: “America can be proud. Not only did she adhere

to the Geneva Conventions, she went further than she had to, because we’re

better than the terrorists.”

Besides the amendments that would have struck the ban on habeas corpus cases,

the others that failed included one that would have established a sunset on the

measure to allow Congress to reconsider it in five years and one that would have

require the C.I.A. to submit to Congressional oversight.

Another failed amendment would have required the State Department to inform

other nations of what interrogation techniques it considered illegal for use on

American troops, a move intended to prompt the administration to say publicly

what techniques it considers out of bounds.

Senate Passes Broad New Detainee Rules, NYT, 29.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/29/washington/29detain.html?hp&ex=1159588800&en=6cbabb925a41f7b0&ei=5094&partner=homepage

News Analysis

Waging the War on Terror: Report Belies

Optimistic View

September 27, 2006

The New York Times

By DAVID E. SANGER

WASHINGTON, Sept. 26 — Three years ago,

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld wrote a memo to his colleagues in the

Pentagon posing a critical question in the “long war’’ against terrorism: Is

Washington’s strategy successfully killing or capturing terrorists faster than

new enemies are being created?

Until Tuesday, the government had not publicly issued an authoritative answer.

But the newly declassified National Intelligence Estimate on terrorism does

exactly that, and it concludes that the administration has failed the Rumsfeld

test.

Portions of the report appear to bolster President Bush’s argument that the only

way to defeat the terrorists is to keep unrelenting military pressure on them.

But nowhere in the assessment is any evidence to support Mr. Bush’s

confident-sounding assertion this month in Atlanta that “America is winning the

war on terror.’’

While the spread of self-described jihadists is hard to measure, the report

says, the terrorists “are increasing in both number and geographic dispersion.”

It says that a continuation of that trend would lead “to increasing attacks

worldwide’’ and that “the underlying factors fueling the spread of the movement

outweigh its vulnerabilities.’’

On Tuesday evening the White House issued what it called a fact sheet lining up

the intelligence estimate’s findings with President Bush’s own words in recent

months, comparing, for example, the report’s account of the the spread of new

terror cells independent of Al Qaeda to Mr. Bush’s references to “homegrown

terrorists’’ from Madrid to Britain.

But there is a difference in tone between Mr. Bush’s public statements and the

classified assessment that is unmistakable.

The report says that over the next five years “the confluence of shared purpose

and dispersed actors will make it harder to find and undermine jihadist

groups.’’

It also suggests that while democratization and “exposing the religious and

political straitjacket that is implied by the jihadists’ propaganda’’ might dim

the appeal of the terrorist groups, those factors are now outweighed by the

dangerous brew of fear of Western domination, the battle for Iraq’s future and

the slow pace of real economic or political progress.

Yet the intelligence report bears none of Mr. Bush’s long-range optimism. Rather

it dwells on Mr. Rumsfeld’s darker question, which he put cheekily as, “Is our

current situation such that ‘the harder we work, the behinder we get?’ ”

Tuesday’s declassified report asked a more subtle version of that question. It

notes that while democratization might “begin to slow the spread’’ of extremism,

the “destabilizing transitions’’ caused by political change “will create new

opportunities for jihadists to exploit.’’

And while Mr. Bush talks often of transforming the Middle East, the report

speaks of the “vulnerabilities’’ created by the fact that “anti-U.S. and

antiglobalization sentiment is on the rise and fueling other radical

ideologies.’’

The result, it said, was that other groups around the world are radicalizing

“more quickly, more widely and more anonymously in the Internet age.’’

In short, it describes a jihadist movement that, for now, is simply outpacing

Mr. Bush’s counterattacks.

“I guess the overall conclusion that you get from it is that we don’t have

enough bullets given all the enemies we are creating,’’ said Bruce Hoffman, a

professor of security studies at Georgetown University.

What was most remarkable about the intelligence estimate, several experts said,

was the unremarkable nature of its conclusions.

“At one level it is unsurprising stuff,’’ said Paul Pillar, who was the national

intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia on the intelligence

council until last year. “But there is definitely much there that you haven’t

heard the president say,’’ he added, “including the role that Iraq has played’’

in inspiring disaffected Muslims to join an anti-American jihadist movement.

Administration officials expressed their certainty on Tuesday that the leak of

parts of the report was an example of politically inspired cherry picking, to

use a term from earlier arguments over intelligence about unconventional

weapons.

“Here we are, coming down the stretch in an election campaign, and it’s on the

front page of your newspapers,’’ Mr. Bush said at a news conference with

President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan. “Isn’t that interesting? Somebody has

taken it upon themselves to leak classified information for political

purposes.’’

And at the center of the political debate is Iraq. Frances Fragos Townsend, the

director of homeland security at the White House, used a conference call with

reporters on Tuesday evening to call attention to the intelligence finding that

“the Iraq conflict has become a cause célèbre for jihadists, breeding a deep

resentment of U.S. involvement in the Muslim world, and cultivating supporters

for the global jihadist movement.’’

“Should jihadists leaving Iraq perceive themselves and be perceived to have

failed,’’ the findings went on, “we judge fewer fighters will be inspired to

carry on the fight.’’

Ms. Townsend argued that “this really underscores the President’s point about

the importance of our winning in Iraq,’’ she said.

As a political matter, at least for the next few weeks, the intelligence

findings will only fuel the argument over Iraq on both sides. Mr. Bush has grown

increasingly insistent that nothing he has done in Iraq has worsened terrorism.

America was not in Iraq during the first World Trade Center attack in 1993, he

said, or during the bombings of the U.S.S. Cole or embassies in Africa, or on

9/11.

But that argument steps around the implicit question raised by the intelligence

finding: whether postponing the confrontation with Saddam Hussein and focusing

instead on securing Afghanistan, or dealing with issues like Iran’s nascent

nuclear capability or the Middle East peace process, might have created a

different playing field, one in which jihadists were deprived of daily images of

carnage in Iraq to rally their sympathizers.

Waging the War on Terror: Report Belies Optimistic View, NYT, 27.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/27/washington/27assess.html?hp&ex=1159416000&en=4390e3dcfece8e76&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Backing Policy, President Issues Terror

Estimate

September 27, 2006

The New York Times

By MARK MAZZETTI

WASHINGTON, Sept. 26 — Portions of a National

Intelligence Estimate on terrorism that the White House released under pressure

on Tuesday said that Muslim jihadists were “increasing in both number and

geographic dispersion” and that current trends could lead to increasing attacks

around the globe.

The report, a comprehensive assessment of terrorism produced in April by

American intelligence agencies, said the invasion and occupation of Iraq had

become a “cause célèbre” for jihadists. It identified the jihad in Iraq as one

of four underlying factors fueling the spread of the Islamic radicalism, along

with entrenched grievances, the slow pace of reform and pervasive anti-American

sentiment.

The intelligence estimate said American-led counterterrorism efforts in the past

five years had “seriously damaged the leadership of Al Qaeda and disrupted its

operations.” But it said that Al Qaeda continued to pose the greatest threat to

American interests among terrorism organizations, and that the global jihadist

movement overall was “spreading and adapting to counterterrorism efforts.” [Text

and news analysis, Page A16.]

The estimate predicted that over the next five years the factors fueling the

spread of global jihad were likely to be more powerful than those that might

slow it.

The White House ordered portions of the intelligence estimate declassified to

counter what it described as mischaracterizations about its findings in news

reports.

The Bush administration had initially resisted releasing the document but

changed course after being pressured to declassify the report by Republicans,

including Senator Pat Roberts of Kansas, chairman of the Senate intelligence

committee, and by the conservative editorial page of The Wall Street Journal.

At a news conference on Tuesday where he announced the release of portions of

the document, President Bush suggested forcefully that news reports in the past

two days about the document had been based on politically motivated leaks.

“You know, to suggest that if we weren’t in Iraq we would see a rosier scenario,

with fewer extremists joining the radical movement, requires us to ignore 20

years of experience,” Mr. Bush said. He added: “My judgment is: The only way to

protect this country is to stay on the offense.”

The intelligence estimate says that if jihadists who leave Iraq perceive

themselves, or are perceived by others, to have failed, fewer fighters will be

inspired to keep fighting.

Democrats seized on the document’s conclusions as proof that the invasion of

Iraq was a mistake.

“The war in Iraq has made us less safe,” said Senator John D. Rockefeller IV of

West Virginia, the top Democrat on the Senate intelligence committee. Mr.

Rockefeller said the judgments contained in the intelligence estimate “make it

clear that the intelligence community — all 16 agencies — believe the war in

Iraq has fueled terrorism.”

The estimate was the first formal appraisal of the terrorism threat by American

intelligence agencies since the invasion of Iraq began in March 2003. The public

release of any portion of such a document is highly unusual. The White House

declassified fewer than 4 pages of what officials described as a document of

more than 30 pages, saying that to release more of it would endanger

intelligence sources and methods.

The release of the findings added fuel to an intense political debate about the

administration’s record in combating terrorism. Mr. Bush used the news

conference to reassert his view that the Iraq war was not to blame for the

growth of Islamic radicalism.

He also attributed the disclosure of some of the assessment findings to what he

said were government officials leaking classified information to “create

confusion in the minds of the American people” weeks before an important

Congressional election.

The first article on the findings was published Sunday in The New York Times

after more than five weeks of reporting. More than a dozen United States

government officials and outside experts were interviewed for the article,

including employees of several government agencies and both supporters and

critics of the Bush administration.

Democrats also criticized the White House for only declassifying part of the

report, and the House minority leader, Nancy Pelosi of California, tried and

failed to persuade Republicans to agree to a vote that would have shut the doors

of the House of Representatives to allow members to read the entire classified

report.

Officials who have read the entire document said the still-classified portion

contained a more detailed analysis of the impact of the Iraq war on the global

jihad movement. Representative Jane Harman of California, the top Democrat on

the House intelligence committee, said that what the White House released

Tuesday was broadly consistent with the classified portion of the report.

National intelligence estimates are the most authoritative documents that

American intelligence agencies produce on a specific national security issue.

They represent the consensus view of the 16 intelligence agencies in government,

and are approved by John D. Negroponte, director of national intelligence.

The release on Tuesday of portions of the document was the second time that the

Bush administration had come under political pressure to declassify a national

intelligence estimate.

In July 2003, the White House released the principal judgments of an October

2002 National Intelligence Estimate about Iraq’s weapons programs in an attempt

to address a furor over the origins of President Bush’s statement, made in a

State of the Union address, that Saddam Hussein had been trying to buy nuclear

materials in Niger.

In recent months, without disclosing the existence of the intelligence estimate

on terrorism, some senior American intelligence officials have given glimpses

into its conclusions. During a speech in San Antonio in April, Gen. Michael V.

Hayden, who was then Mr. Negroponte’s deputy, said new jihadist networks and

cells were increasingly likely to emerge.

“If this trend continues, threats to the U.S. at home and abroad will become

more diverse and that could lead to increasing attacks worldwide,” General

Hayden said, using the exact language of the intelligence assessment made public

on Tuesday. General Hayden is now director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

But the intelligence assessment paints a starker picture of the role that the

Iraq war is playing in shaping a new generation of terrorist leaders than that

presented either in recent White House documents or in speeches by President

Bush tied to the fifth anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks.

The intelligence report specifically cited the role of the Jordanian terrorist

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who led the Iraqi group Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, in

attracting new recruits for the jihad cause in Iraq, and stated that “should

al-Zarqawi continue to evade capture and scale back attacks against Muslims, we

assess he could broaden his popular appeal and present a global threat.”

He was killed by American forces in June.

Frances Fragos Townsend, the president’s homeland security adviser, suggested to

reporters on Tuesday that the killing of Mr. Zarqawi might ultimately help

dampen the appeal of jihad in Iraq.

At the same time, the report concludes that the increased role of Iraqis in

managing the operations of Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia “might lead veteran foreign

jihadists to focus their efforts on external operations.”

To be successful in combating the spread of a radical ideology, the assessment

states, the United States government “must go well beyond operations to capture

or kill terrorist leaders.”

Backing Policy, President Issues Terror Estimate, NYT, 27.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/27/world/middleeast/27intel.html?hp&ex=1159416000&en=e7cb014f7d4fe4e4&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Deal on terror suspects hits new snag

Updated 9/25/2006 10:49 PM ET

USA Today

By Kathy Kiely and David Jackson

WASHINGON — A compromise proposal on trials

for terrorism suspects came under fire Monday from a key Republican senator and

a former top military lawyer who said the deal would suspend a fundamental legal

right against unlawful detention.

Senate Judiciary Chairman Arlen Specter,

R-Pa., said he is "strongly opposed" to a provision in proposed legislation that

would bar foreigners now held as enemy combatants from challenging their

detention in court.

Specter's opposition could complicate efforts to win congressional approval this

week for a deal worked out Thursday between the White House and three Republican

senators who had balked at President Bush's proposals on interrogations of and

military tribunals for terrorism suspects: John Warner of Virginia, John McCain

of Arizona and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina.

Congress is pressing to complete work on two national security issues before

leaving town to campaign for the Nov. 7 elections. House Armed Services

Committee Chairman Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., said he expects the House to approve

the tribunal legislation Wednesday. Senate debate could begin today.

On the second issue, three Republicans said their concerns about a bill that

would establish rules for telephone surveillance of terrorism suspects have been

satisfied. Sens. John Sununu of New Hampshire, Larry Craig of Idaho and Lisa

Murkowski of Alaska said new provisions requiring more court supervision of

wiretaps have persuaded them to support the bill. Democratic Sens. Dick Durbin

of Illinois, Russ Feingold of Wisconsin and Ken Salazar of Colorado said they

remain concerned that the wiretaps would violate civil liberties.

White House spokeswoman Dana Perino expressed hope that the Republican senators'

announcement on the wiretapping deal will spark quick action on "this vital

program that helps us detect and prevent terrorist attacks."

The White House, however, is less inclined to satisfy Specter's concerns about

the rights of people accused of being terrorists. Perino said the Bush

administration opposes giving such suspects "unfettered access" to regular

courts to lodge protests. She said all legal complaints should go through the

military commissions that would be established under the legislation.

That position drew criticism from a prominent GOP attorney who testified Monday

before the Judiciary panel. "Due process should not be crucified on a cross of

political expediency," said Bruce Fein, a Justice Department lawyer in the

Reagan administration. He urged lawmakers to slow their pre-election rush to set

new rules for CIA interrogations of terror suspects and their trials.

At issue is whether foreigners held on suspicion of terrorist activities should

have the right to go before a judge to challenge the legality of their detention

process known as habeas corpus.

John Hutson, a retired rear admiral in the judge advocate general corps, accused

the Bush administration of seeking to suspend habeas corpus to "cover up"

mistakes at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where detainees are now held.

Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., said that a "significant percentage" of Guantanamo

prisoners have been mistakenly imprisoned and that depriving them of court

challenges is "un-American."

Pentagon spokesman J.D. Gordon said about 320 detainees have been released from

Guantanamo and 130 others have been approved for transfer.

Contributing: Kevin Johnson

Deal

on terror suspects hits new snag, UT, 25.9.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2006-09-25-congress-terrorism_x.htm

Editorial

Chemical Plants, Still Unprotected

September 25, 2006

The New York Times

Congress still has done nothing to protect

Americans from a terrorist attack on chemical plants. Republican leaders want to

give the impression that that has changed. But voters should not fall for the

spin. If the leadership goes through with the strategy it seems to have adopted

last week to secure these highly vulnerable targets, national security will be

the loser.

The federal government is spending extraordinary amounts of money and time

protecting air travel from terrorist attacks. But Congress has not yet passed a

law to secure the nation’s chemical plants, even though an attack on just one

plant could kill or injure as many as 100,000 people. The sticking point has

been the chemical industry, a heavy contributor to political campaigns, which

does not want to pay the cost of reasonable safety measures.

The Senate and the House spent many months carefully developing bipartisan

chemical plant security bills. Both measures were far too weak, but they would

have finally imposed real safety requirements on the chemical industry. The

Republican leadership in Congress blocked both bills from moving forward.

Instead, whatever gets done about chemical plant security will apparently be

decided behind closed doors, and inserted as a rider to a Department of Homeland

Security appropriations bill.

It is outrageous that something as important as chemical plant security is being

decided in a back-room deal. It is regrettable that Susan Collins, Republican of

Maine, the chairwoman of the committee that produced the Senate bill, does not

carry enough influence with her own party’s leadership to get a strong chemical

plant security bill passed. The deal itself, the likely details of which have

emerged in recent days, is a near-complete cave-in to industry, and yet more

proof that when it comes to a choice between homeland security and the desires

of corporate America, the Republican leadership always goes with big business.

Any federal chemical plant law should make it clear that states have the right

to impose stricter requirements to protect their citizens from harm. The Senate

and House bills said this, but the rider apparently will not. A reasonable law

would make it clear that the secretary of homeland security can order chemical

plants to adopt specific safety measures, like replacing highly dangerous

chemicals with ones that pose less of a danger to people in the surrounding

area. The House bill did this, but the rider apparently will not give the

secretary this basic power.

It is likely that the backroom deal will also exempt water treatment and

drinking water facilities from regulation, meaning that millions of Americans

could needlessly be put at risk of an attack on a chlorine tank, and that it

will make the rules about when and how chemical plants must submit safety plans

hopelessly vague.

It is not too late to abandon this bad deal and pass a strong law. In a recent

New York Times/CBS News poll, just 25 percent of those asked approved of the job

Congress is doing. Its handling of the chemical plant security issue gives a

good indication why.

Chemical Plants, Still Unprotected, NYT, 25.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/25/opinion/25mon1.html

U.S. to relax liquid ban on airliners

Updated 9/25/2006 1:40 PM ET

By USA TODAY staff

ARLINGTON, Va. — The federal government will

allow many liquids and gels back onto airliners, partially lifting a ban

instituted last month after a plot to bomb jets flying into the United States

was foiled, federal officials announced this morning.

"We now know enough to say that a total ban is

no longer needed from a security point of view," said Kip Hawley, head of the

Transportation Security Administration, at a news conference this morning at

Reagan National Airport near Washington, D.C. He said two changes would go into

effect Tuesday on liquids or gels:

•Most liquids and gels, including toiletries such as toothpaste, gel deodorants

and lip gloss, will be allowed in carry-on luggage — if the individual

containers are 3 ounces or less and if all of the items will fit into a single,

quart-size clear plastic bag.

•Liquids purchased in the so-called "sterile area" — the area of the airport

inside the security checkpoint — can be brought onto aircraft.

The tougher airport screening procedures were put in place in August after

British police broke up a terrorist plot to assemble and detonate bombs using

liquid explosives on airliners crossing the Atlantic Ocean from Britain to the

U.S.

At the time, the Homeland Security Department briefly raised the threat level to

"red," the highest level, for flights bound to the United States from Britain.

All other flights were at "orange" and will remain at orange, the second-highest

level, and will not change "any time in the near future," Deputy Homeland

Security Director Michael Jackson said at the news conference.

The TSA made the change after conducting, with the assistance of the FBI and

other government experts, "extensive explosives testing to get a better

understanding of this specific threat," according to a statement on the TSA's

website.

The agency also will be changing some of its security members at airports,

including additional random screenings and canine patrols and new air cargo

security efforts, according to a TSA news release.

Travelers reacted positively. "For two-day trips, this will be easier, but I put

safety over convenience," said Martin Allred, a commercial photographer from New

Orleans who flew to Denver this morning. Allred said he had been forced to check

his bags repeatedly since the ban went into effect.

Before boarding a flight this morning form Charlotte to Denver, Janella D'Amore

was forced to throw away a cup of Starbucks coffee. "I have really dry hands and

I couldn't bring my lotion" onto the plane because of the ban, said the

26-year-old Denver resident.

Rev. Kenneth Arnold, 62, of New York, said in Denver that he was troubled by the

regular changes in security rules. "The kind of response we saw to this is part

of a lack of clear thinking. What people find discouraging is the sense of

chaos," he said.

Signs, video screens and announcements at O'Hare International Airport in

Chicago still advised travelers this morning that, "effective immediately,"

liquids and gels are banned from carry-ons.

Roger Rhomberg was drinking a bottle of Snapple diet iced tea outside the

security gate in O'Hare's Terminal 1 because he knew he couldn't carry it

through the checkpoint.

"It was a slight inconvenience to not be able to take a beverage on the plane,

especially when it's a long flight," said Rhomberg, 41, a furniture sales

representative from Oak Park, Ill., who was flying to Seattle. Checking and

retrieving his bag added 30 minutes to each trip, he said, and he's happy the

rules are changing.

"I'm all for erring on the side of caution," he said, "but it seems like once

you're past security, having liquids shouldn't be a problem."

Kourtney Hentges, 19, was flying this morning from Chicago to Spokane, Wash.,

for a wedding. She lives in Avilla, Ind., and said the rules that took effect

last month mostly made sense to her.

"The liquids are one thing — if they're a beverage or whatever," she said, "but

I don't necessarily think you need lip gloss and hand lotion to fly. I think

it's pointless to throw a fit because you can't bring them."

The announcement also brought praise from an airport trade group. "Obviously,

there's been a lot of unhappiness," said Richard Marchi, senior adviser to the

Airports Council International. "They're right to find a way to ease the burden

and maintain a reasonable level of security."

Contributing: Judy Keen in Chicago, Tom Kenworthy in Denver, Randy Lilleston

in McLean, Va. and the Associated Press.

U.S.

to relax liquid ban on airliners, UT, 25.9.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/travel/flights/2006-09-25-airlines-liquids_x.htm

Iraq war fuels Islamic radicals: retired

U.S. general

Mon Sep 25, 2006 11:32 PM ET

Reuters

By Susan Cornwell

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The conduct of the Iraq

war fueled Islamic fundamentalism across the globe and created more enemies for

the United States, a retired U.S. Army general who served in the conflict said

on Monday.

The views of retired Army Maj. Gen. John Batiste buttressed an assessment by

U.S. intelligence agencies, which intelligence officials said concluded the war

had inspired Islamist extremists and made the militant movement more dangerous.

The Iraq conflict, which began in March 2003, made "America arguably less safe

now than it was on September 11, 2001," Batiste, who commanded the 1st Infantry

Division in Iraq in 2004-2005, told a hearing on the war called by U.S. Senate

Democrats.

"If we had seriously laid out and considered the full range of requirements for

the war in Iraq, we would likely have taken a different course of action that

would have maintained a clear focus on our main effort in Afghanistan, not

fueled Islamic fundamentalism across the globe, and not created more enemies

than there were insurgents," Batiste said.

U.S. intelligence chief John Negroponte refuted that charge at a Washington

dinner late Monday, denying the Iraq war had increased the terrorism threat to

the United States.

"I think we could safely say that we are safer and that the threat to the

homeland itself has, if anything, been reduced since 9/11," the U.S. director of

national intelligence said in response to intelligence leaks on Iraq and

terrorism that have engulfed the Bush administration in recent days.

"We are more vigilant. We are better prepared," he said.

Batiste, who was among retired generals who called for the resignation of

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld earlier this year, poured scorn on the war

plan along with two other retired military men at a hearing called by Senate

Democrats.

HARSH TREATMENT MAKES ENEMIES

They said the Pentagon let the insurgency grow by not sending enough U.S. troops

and made enemies by abusing Iraqis.

"Probably 99 percent of those people were guilty of absolutely nothing," Batiste

said of Iraqis U.S. forces held at Abu Ghraib prison. "But the way we treated

them, the way we abused them, turned them against the effort in Iraq forever."

At one point, retired Marine Corps Col. Thomas Hammes derisively referred to the

U.S. Iraq strategy as "Whack-a-mole," a fairground game where the player uses a

big hammer to swat mechanical moles as they pop up from holes.

Hammes said the United States needed another 10 years to succeed in Iraq, while

retired Army Maj. Gen. Paul Eaton said the Army needed another 60,000 troops to

finish the job. There are 142,000 U.S. troops in Iraq.

Hammes helped establish bases for Iraqi armed forces in 2004, while Eaton

trained Iraqi military and police in 2003-4.

Most Democrats are pushing for a plan to start withdrawing U.S. forces, but

without a deadline to finish the withdrawal.

Democrats have seized upon the National Intelligence Estimate to undermine the

image fostered by President George W. Bush and Republicans as the party best

able to stop terrorism before November elections in which control of Congress is

at stake.

The classified intelligence document said Iraq had become the main recruiting

tool for the Islamic militant movement as well as a training ground for

guerrillas, according to current and former intelligence officials.

Negroponte told his audience at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for

Scholars that news accounts exaggerated the NIE's emphasis on Iraq by

overlooking a range of other factors including slow progress in economic, social

and political reform throughout the Muslim world.

(Additional reporting by David Morgan and Matt Spetalnick)

Iraq

war fuels Islamic radicals: retired U.S. general, R, 25.9.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=politicsNews&storyID=2006-09-26T033158Z_01_N25287562_RTRUKOC_0_US-SECURITY-USA.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C5-politicsNews-2

Spy Agencies Say Iraq War Worsens Terror

Threat

September 24, 2006

The New York Times

By MARK MAZZETTI

WASHINGTON, Sept. 23 — A stark assessment of

terrorism trends by American intelligence agencies has found that the American

invasion and occupation of Iraq has helped spawn a new generation of Islamic

radicalism and that the overall terrorist threat has grown since the Sept. 11

attacks.

The classified National Intelligence Estimate attributes a more direct role to

the Iraq war in fueling radicalism than that presented either in recent White

House documents or in a report released Wednesday by the House Intelligence

Committee, according to several officials in Washington involved in preparing

the assessment or who have read the final document.

The intelligence estimate, completed in April, is the first formal appraisal of

global terrorism by United States intelligence agencies since the Iraq war

began, and represents a consensus view of the 16 disparate spy services inside

government. Titled “Trends in Global Terrorism: Implications for the United

States,’’ it asserts that Islamic radicalism, rather than being in retreat, has

metastasized and spread across the globe.

An opening section of the report, “Indicators of the Spread of the Global

Jihadist Movement,” cites the Iraq war as a reason for the diffusion of jihad

ideology.

The report “says that the Iraq war has made the overall terrorism problem

worse,” said one American intelligence official.

More than a dozen United States government officials and outside experts were

interviewed for this article, and all spoke only on condition of anonymity

because they were discussing a classified intelligence document. The officials

included employees of several government agencies, and both supporters and

critics of the Bush administration. All of those interviewed had either seen the

final version of the document or participated in the creation of earlier drafts.

These officials discussed some of the document’s general conclusions but not

details, which remain highly classified.

Officials with knowledge of the intelligence estimate said it avoided specific

judgments about the likelihood that terrorists would once again strike on United

States soil. The relationship between the Iraq war and terrorism, and the

question of whether the United States is safer, have been subjects of persistent

debate since the war began in 2003.

National Intelligence Estimates are the most authoritative documents that the

intelligence community produces on a specific national security issue, and are

approved by John D. Negroponte, director of national intelligence. Their

conclusions are based on analysis of raw intelligence collected by all of the

spy agencies.

Analysts began working on the estimate in 2004, but it was not finalized until

this year. Part of the reason was that some government officials were unhappy

with the structure and focus of earlier versions of the document, according to

officials involved in the discussion.

Previous drafts described actions by the United States government that were

determined to have stoked the jihad movement, like the indefinite detention of

prisoners at Guantánamo Bay and the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal, and some

policy makers argued that the intelligence estimate should be more focused on

specific steps to mitigate the terror threat. It is unclear whether the final

draft of the intelligence estimate criticizes individual policies of the United

States, but intelligence officials involved in preparing the document said its

conclusions were not softened or massaged for political purposes.

Frederick Jones, a White House spokesman, said the White House “played no role