|

History > 2006 > USA > State Justice

(III)

Jeffrey Mark Deskovic with his mother, Linda

McGarr,

outside the Westchester County Courthouse in White Plains.

He had served 16 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times

DNA Evidence Frees a Man Imprisoned

for Half His Life NYT

21.9.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/21/nyregion/21dna.html

Broken Bench

How a Reviled Court System Has Outlasted

Many Critics

September 27, 2006

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GLABERSON

“A farce in these days,” Gov. Alfred E. Smith

pronounced New York State’s town and village courts in 1926.

“An outworn system,” said his successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, not long after a

state commission called it “a feeble office respected by no one.” A few years

after that, another commission said the local court system had “lost all contact

with reality.”

In all, at least nine commissions, conferences or other state bodies — including

representatives of both major political parties and all three branches of

government — have denounced the local courts over the last century, joined by at

least two governors and several senior judges.

Their language has often been blistering, and their point has been the same:

These courts, with their often primitive trappings and amateur judges, are an

anachronism that desperately needs to be overhauled or discarded.

Although they are key institutions of justice in more than 1,000 small towns and

suburbs across New York, trying misdemeanor cases and lawsuits, a vast majority

of the justices who run them are not lawyers, and receive only a few days’ legal

training. The justices are often elected in low-turnout races, keep few records

and operate largely without supervision — leaving a long trail of injustices and

mangled rulings.

Yet these justice courts, as they are known, remain essentially as they were

when New Yorkers started complaining nearly a century ago. In recent weeks,

state officials have decided to take some steps to increase training,

supervision and record-keeping. But the cries for any sweeping change have all

but died out over the last few decades, even as the abuses have continued.

One way to understand why a much-criticized institution has come to seem so

entrenched is to revisit three big battles over the justice courts. In each, the

people seeking to change the system tried in a different arena: the Legislature,

the voting booths and the higher courts. And each time, their defeat was so

stinging that it effectively killed any further discussion there:

¶In 1962, state leaders accomplished something they had been trying to do for

more than a century, revamping a state court system that was badly out of date.

But in several back-room political maneuvers, they left the justice courts

untouched, passed the task of altering the system to local governments, and

added a maze of procedural barriers that made any major change difficult.

¶In 1967, local activists took up the cause in Rockland County, one of the few

counties where a push to replace the justice courts made some headway; a

referendum was held on the issue. But a fiercely emotional campaign vanquished

the proposal, and helped create a sense in other counties that fighting the

system was futile.

¶And in 1983, a challenge to the system’s constitutionality reached the state’s

highest court, the Court of Appeals. Attorneys for an upstate teenager facing a

jail sentence argued that the right to a lawyer, guaranteed by the Constitution,

was meaningless if the judge lacked the training to understand the lawyer’s

arguments.

That appeal failed by a single vote. New Yorkers, the majority on the

seven-member court decreed, do not have to be tried by a judge schooled in the

law — a ruling that has stood ever since.

In interviews, people who were deeply involved in these episodes — including

political deal-making that took place out of public view and was never reported

— pointed to a battery of forces that have doomed change: The powerful idea that

communities should choose their own destinies, including their own judges. The

considerable costs of updating courtrooms and hiring lawyers to preside. The

always-popular calls to keep lawyers out of people’s lives. And, not least, the

power of the justices, who are often important players in local politics, wired

into the same party mechanisms that produce the state’s lawmakers, judges and

governors.

Dale C. Robbins, a former Republican supervisor of Busti, a small town in

western New York, said he and others who tried to replace the justice courts in

the 1990’s ran into a buzz saw of resistance from local justices fighting for

their jobs, and something of a populist uprising fueled by suspicion of the

lawyers who would be judges in any new system.

He said the defeat was typical of the gridlock on many big issues in New York.

“Nothing gets done,” he said. “Who wants to face this battle when there are so

many other battles you have to fight?”

A Moment in Albany

It was January 1959. The new governor and political star, Nelson A. Rockefeller,

was making his first address to the Legislature in Albany. “The highest

priority” of his administration, he promised, would be modernizing the state

court system.

Court reform, he knew, was a popular issue he could ride, yellowing papers in

the Rockefeller archive show. People across the state were sick of the slow,

confusingly organized system and the patronage appointees — many of them

unqualified, unresponsive or corrupt — who filled it from top to bottom.

Complaints that had been pouring in for decades had reached critical mass in

recent years, as the latest state panel to tackle court reform, known as the

Tweed Commission, drew up detailed proposals for change.

Soon after his speech to lawmakers, Governor Rockefeller appointed his young

counsel, Robert MacCrate, to draw up amendments to the State Constitution that

would be needed to reorganize the courts, and then to marshal support in the

Legislature.

But Mr. MacCrate quickly learned that the lowliest part of the court system

posed one of the highest political hurdles.

Governor Rockefeller, with his elite background and downstate roots, had to be

careful not to offend the rural upstate powers in his own party, whom he was

trying to convince that he was a real Republican. And, Mr. MacCrate said in an

interview for this article, any effort to change the justice courts, a prime

source of the party’s patronage, would be “really shaking the tree.”

Upstate Republicans often spoke as if criticism of the system was an attack on a

way of life. “You boys from New York City have never seen a justice court,”

State Senator Austin W. Erwin, a central player in the courts battle, said

during a debate that year. “These justices are the backbone of honest-to-God

human justice in our state.”

Governor Rockefeller, for all his talk of change, was surrounded by staunch

defenders of the justice courts. Many were former justices, including Senator

Erwin and L. Judson Morhouse, then the state Republican chairman and one of the

governor’s earliest supporters.

The justices of the peace “were inside the system,” Elizabeth T. Schack, who led

the League of Women Voters’ lobbying for court reform, said in an interview.

Back in the legislators’ districts, too, the justices were powers to be reckoned

with. “They were often people of importance and influence” who knew the

lawmakers personally, Mrs. Schack said. “And you don’t like to go up against

your friends.”

Most important, Mr. MacCrate said, upstate Republicans held such power in the

Legislature that the administration knew that court reform could not pass

without them. “We would find a way to bring them around,” he said.

They didn’t have to find a way; it came to them. Mr. MacCrate said that Fred

Young, an influential state Court of Claims judge whom Governor Rockefeller

would later choose as state Republican chairman, soon approached with an offer.

“Bob, if you take out that provision about abolishing the justices of the

peace,” Mr. MacCrate recalled him saying, “I’ll have the votes for you” to

approve statewide court reform that day or the next.

The deal was made.

That breakthrough would allow the entire court structure in New York to be

streamlined and brought for the first time under centralized control. Yet while

it included a requirement that local justices receive some basic training, it

largely ensured there would be no other change in the biggest piece of the

system: the hundreds of town and village courts.

“That was a turning point in terms of understanding how strong the opposition

was,” recalled Fern Schair, the former chairwoman of the state’s leading

court-reform group, the Committee for Modern Courts.

But the justices and their supporters did not stop there. To keep future

legislatures from tampering with the system, they persuaded the administration

to adopt language requiring a local referendum for any move to replace the town

courts with more professional district courts. And for that referendum to pass,

a simple majority of votes would not suffice; whether in a county or part of

one, the proposal would have to win separate majorities in both urban and rural

areas, so city dwellers could not impose modern courts on their country

neighbors.

Even that, it turned out, was not enough. A year later, as Mr. MacCrate moved to

secure approval from lawmakers, supporters of the justice courts demanded a

provision requiring a majority vote in each town, Mr. MacCrate wrote in a memo.

Towns where the referendum was defeated would be left out of any new system — a

complication that would further discourage any reform effort.

They got their provision.

New Yorkers approved the court-reform amendment at the polls, and to this day,

those protections for the justice courts are enshrined in the State

Constitution. No place in New York has replaced its town and village courts

since western Suffolk County began a district court system in 1962 — the year

Governor Rockefeller signed his reforms into law.

A Showdown in Rockland

“If you oppose ‘school busing,’ Expanded Welfare, Down zoning, Charter

Government, Mob rule legislation, Crime in the Street, Black Power,” vote no on

Proposition No. 1, said the newspaper advertisement by the Conservative Party.

But Proposition No. 1 was not about any of those things. It was a ballot

proposal to replace justice courts with a system of district courts in which the

judges would be lawyers. After all the battles in Albany, it was the people’s

turn to decide.

This was 1967 in Rockland County, a rural place fast becoming a suburb as new

residents arrived by the carload from nearby New York City. Some newcomers were

alarmed by their encounters with eccentric justices who could wield sweeping

powers over people’s lives.

“The feeling was, they weren’t professionals and they were too closely connected

to people who brought their cases to court,” Gloria English, a New City resident

who worked for the proposal as a member of the League of Women Voters, said in a

recent interview. “They often heard their friends’ cases.”

The league had several potent allies, including the county bar association and

some leaders of both major political parties. The Democratic Party sponsored an

ad saying it was high time the courts were modernized. The leading newspaper in

the county ran editorials urging that the justice courts be brought into the

20th century.

On the other side were the justices and their supporters, including leaders of

the county Conservative Party. They warned that the fancy new courts and their

lawyer judges would cost more. The bar association estimated that expense at

about $200,000 a year countywide, about $50,000 more than justice courts cost at

the time. “I used that to bring to the attention of people: ‘It’s just another

boondoggle,’ ” William E. Vines, then a justice in Clarkstown with a local

insurance business, recalled in a recent interview.

There was also grass-roots backing for the justice courts, particularly among

longtime residents. Arnold Becker, who was county public defender, said some

people felt that familiar local justices would be more lenient than professional

district judges.

But the campaign also played on emotions that had little to do with law or

money.

The referendum’s opponents were not shy about fanning resentment toward

outsiders. The warnings about mob rule and black power spoke to fears about

turmoil in the cities, and about the city people moving in. There were stirring

appeals to patriotism.

“Justice courts are as much of your American heritage as those Stars and

Stripes,” one justice told a group of Jaycees two weeks before the election.

“Don’t let them take it away.”

Adele Garber, then a young mother who had moved up from Queens and gone door to

door on behalf of the ballot proposal, said that kind of passion easily

overpowered her side’s arguments about fairness and efficiency. Voters without a

vested interest in the justice courts, she said, did not seem to care much.

“It’s not a nice, sexy issue,” she said.

The referendum lost by a 2-to-1 ratio.

Mrs. Garber said the experience left her cynical, and she was not the only one.

The Rockland vote and similar defeats in other counties helped create the

impression that such fights are impossible to win.

Because of a change in state policy since then, if a county adopted a district

court system today, the state would pick up the cost. Statewide, that expense

could be significant, perhaps tens of millions of dollars.

County governments, though, might save millions by consolidating their many

justice courts into fewer, more centralized district courts. But change has been

stymied.

Keith D. Ahlstrom, chairman of the Chautauqua County Legislature, said that

while he and others have long seen a need to modernize the courts there, the

referendum process was so cumbersome it would almost certainly fail. For now, he

and other officials are backing a state bill that would permit a few justice

courts to merge to cut costs.

“We need to have a small success,” he said.

A Near-Miss in Court

The case was unremarkable: a teenager was arrested in Conesus, near Rochester,

in 1981 and charged with menacing and trespassing. He was identified only as

Charles F. because he was a minor. He faced up to a year in jail.

But his lawyer, J. Michael Jones, saw that the case had the potential to bring

down the justice-court system in New York, and possibly in other states. The

United States Supreme Court had ruled 20 years earlier that any defendant facing

a jail sentence was entitled to a lawyer. But what good was that right, he

asked, if the judge — like the town justice Charles F. faced — could not follow

the lawyer’s arguments?

In a recent interview, Mr. Jones recalled that he spent thousands of dollars out

of his own pocket taking the case through the appeals courts. “I thought this

was a perfect opportunity for us to upgrade the local court system,” he said.

The time seemed ripe. In recent years, there had been a nationwide movement to

recognize defendants’ rights. Justice courts around the country had been

revamped after a 1967 presidential crime commission noted their long record of

“incompetence.”

Some of the biggest changes were prompted by the courts. In 1974, the California

Supreme Court ruled that imprisonment by a judge who did not have legal training

was a violation of due process, and essentially ordered an end to the state’s

justice courts.

“It seemed there was an opportunity, a movement afoot that was going to provide

a court remedy where there had never been a legislative solution,” said Rene H.

Reixach Jr., a Rochester lawyer who wrote a friend-of-the-court brief in the

Charles F. case for the New York Civil Liberties Union.

A United States Supreme Court ruling in 1976 appeared to offer the means for

challenging New York’s system. The court upheld the jailing of a Kentucky man by

a justice who was a coal miner with no legal training, but only because state

law guaranteed defendants tried by nonlawyer justices the automatic right to a

new trial before a judge who was a lawyer.

In New York, however, there is no such right. A defendant can ask a county judge

to take the case, but the judge can refuse — as happened in the Charles F. case.

When the case reached the state’s top court, the Court of Appeals, in 1983,

Charles F.’s lawyers argued that in an era of increasingly complex legal

protections for defendants, it was basic fairness that a person facing jail

should have a judge trained to understand those protections. At the court’s

chamber in Albany, Mr. Jones remembered, “we had lawyers from New York City who

couldn’t believe we had this system.”

The court, which was developing a reputation for protecting defendants’ rights,

seemed receptive. On it was the state’s chief judge at the time, Lawrence H.

Cooke, and the two judges who would succeed him: Sol Wachtler and Judith S.

Kaye.

Mr. Wachtler, in a recent interview, said the three strongly agreed that the

state’s use of justices without law schooling was a problem. “There was

unquestionably a sentiment on our parts that this is just not right,” he said.

But when the vote came, they were on the losing side of a 4-to-3 decision. New

Yorkers, the majority ruled, had no absolute right to be heard by a judge

trained in the law.

Richard D. Simons, the only surviving judge in that majority, said in an

interview that the case posed a narrow legal issue: whether New York provided

sufficient opportunity for a higher-court trial. The larger matter of the

justice courts’ fairness, he said, was for the Legislature to decide.

Mr. Wachtler said he believed that the case would have gone the other way if it

had come to the Court of Appeals just a year or two later, given changes in the

court’s makeup and stance on defendants’ rights.

But the court has not grappled with the issue since. Mr. Reixach, the Rochester

lawyer, said the ruling discouraged him and others from raising further

challenges. “The Charles F. case, whether you agreed with it or not,” he said,

“sealed the fate of the justice-court system in the state for a very long time.”

Judge Kaye, who wrote the dissenting opinion, has since become a champion of

court reform as New York’s chief judge, heading the Court of Appeals and the

administration of all the courts. But the legislation she has proposed to

modernize the system since taking office in 1993 has consistently omitted the

justice courts.

Only this summer did Judge Kaye address problems in the local courts, after the

state comptroller warned that they could be mishandling millions of dollars, and

after a commission she created to study legal services for the poor reported

that those courts were routinely trampling on people’s rights.

Her office has said that while it has limited control over the justice courts,

it would begin trying to remedy some of their flaws, with measures that do not

require legislative approval.

Those steps are the most ambitious attempted in several decades, but their very

nature underscores the courts’ deficiencies: Justices, according to the state’s

plan, will get two weeks of initial training instead of six days. For the first

time, all justices will be given computers, fax machines and tape recorders, and

be required to tape proceedings. A supervising judge will be named in each

judicial district to oversee them.

And the improvements do not touch what critics of the justice courts have

repeatedly said are their gravest defects: the use of part-time justices who are

not lawyers, the reliance on towns and villages to finance the courts, and the

state’s weak authority over the courts.

Tackling those issues would involve the Legislature — and invite another battle.

Judge Kaye declined requests for an interview.

One of the justice courts’ most powerful defenders has been the State

Association of Towns. Its executive director, G. Jeffrey Haber, said the group

would be ready for another fight.

“If it came up,” he said, “we would take the same position that we did before.”

How a

Reviled Court System Has Outlasted Many Critics, NYT, 27.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/27/nyregion/27courts.html?hp&ex=1159416000&en=1dafffc95aa24a70&ei=5094&partner=homepage

NYT

September 25, 2006

Delivering Small-Town Justice With a Mix of

Trial and Error NYT

26.9.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/26/nyregion/26courts.html

Broken Bench

Delivering Small-Town Justice With a Mix of

Trial and Error

September 26, 2006

the New York Times

By WILLIAM GLABERSON

DUANE, N.Y. — Gary Betters thought he

understood the law as well as any average American. A school psychologist, he

wanted $1,588.60 he said the nearby village of Malone owed him for helping run a

summer recreation program. When he brought a small claim in Duane Town Court, he

expected that the judge would listen to both sides, then rule.

Like many others who go to court across New York State, he got a crash course in

the strange ways of small-town justice.

Although no one showed up to defend the village, Justice William J. Gori started

the trial anyway. Although the judge had Mr. Betters testify at length, he

neglected to have him swear to tell the truth. And although Justice Gori told

Mr. Betters he had another week to submit more evidence, the judge went ahead

and decided the case anyway.

Mr. Betters received the news in a letter from the court: his case had been

dismissed. No reason was given. “I cannot understand how a defendant can win

when they don’t even show up,” he said in an interview.

The State Commission on Judicial Conduct figured out how. Justice Gori, it

seems, had gone to the village offices in Malone before the trial, interviewed

the village’s chief witness, then informed the village lawyer that he had

decided to throw out the case.

Justice Gori told the commission that he had never heard of the elementary legal

rule that bars a judge, except in the most extraordinary circumstances, from

secret contact with one side of a case. “It’s not even explained in my manual,”

he said.

An unfamiliarity with basic legal principles is remarkably common in what are

known as the justice courts, legacies of the Colonial era that survive in more

than 1,000 New York towns and villages.

For generations, justices have hailed them as “poor man’s courts,” where

ordinary people can get simple justice with little formality or expense. But

there are few more vivid spots to view their shortcomings than here in one of

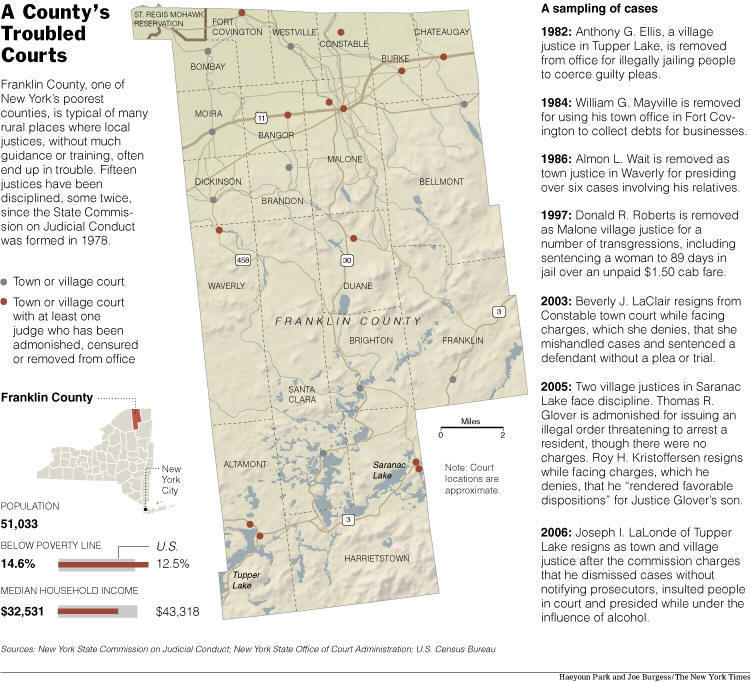

New York’s poorest corners: Franklin County, a place of rugged beauty on the

Canadian border where only one of the 32 local justices is a lawyer.

The county’s justices have repeatedly drawn the attention of state judicial

conduct officials, with 15 publicly disciplined since the late 1970’s, some

twice. Justice Gori’s errors pale in comparison with those of some others: One

justice freed a rape suspect on bail as a favor to a friend. Another sentenced a

welfare recipient to 89 days in jail after she failed to pay a $1.50 cab fare.

Franklin County justices have presided drunk, fixed cases and denied lawyers to

defendants. One failed to appoint a lawyer for a 19-year-old mentally retarded

alcoholic.

Here in Duane, a speck of a town in the center of the county, Justice Gori is in

many ways a typical small-town New York justice.

A bricklayer and a former dog trainer with a high school education, he is an

approachable man of 59, in jeans hitched up with suspenders. On Thursday nights

he ambles down to the volunteer firehouse to hold court, such as it is. His

grasp of the law is somewhat shaky. His temper sometimes gets the better of him.

He has no judge’s bench, few law books and no court clerk. He is something of an

accidental judge, occupying the position for nearly a decade largely because no

one else wants it, people here say. Although state officials have reprimanded

him twice for fundamental lapses in the conduct of his job, few Duane voters

seemed to know or care. “Nobody’s ever asked a question about it,” Justice Gori

said.

He seems well-intentioned enough. Like many justices, he describes his job as

public service, and he says he studies the law for several hours every week.

But there is evidence that that may not be enough. When the judicial conduct

commission called Justice Gori to account for his handling of Mr. Betters’s

case, his defense was startling, a transcript of the hearing shows. His own

lawyer blamed the state for running the justice courts as it does: Judges, he

said, with so little training — six days of classes, and a 12-hour refresher

course once a year — could not possibly know the basic rules for handling a

lawsuit.

The county’s district attorney, Derek P. Champagne, says that when he took

office five years ago, he had to drop hundreds of criminal cases because

justices had failed to take any action for so long. Mr. Champagne says his staff

of four full-time prosecutors is too small even to regularly visit the justice

courts, which are separated by great distances.

Franklin County is bigger than Rhode Island. But it has only one higher court

judge, in the county court in Malone. So the part-time town and village justices

— plumbers, meat cutters and school bus drivers — are often the last word on the

law here, with the power to issue search warrants, conduct trials, put some

people in jail and let friends go free.

“The reality is, you basically have to have no qualifications other than be a

voter to put someone in jail, and that’s a very alarming situation,” Mr.

Champagne said. “To throw a layperson — some of whom don’t have a high school

degree — in that position is just a recipe for disaster.”

A Night in Court

“Town of Duane Justice Court is now in session,” Justice Gori announced.

Four bare fluorescent bulbs provided the only light in the roughly finished

meeting room that becomes a court every few weeks. There was a portable bar

against one wall, and a glimpse of the firehouse kitchen, with its jumble of old

soda bottles and coffeepots. The American flag tacked to the wall had to be

pulled back to allow the judge to get at the thermostat on this icy winter

night.

At two pushed-together folding tables sat a nervous teenager, in court to answer

speeding tickets, next to his clench-jawed father. A state trooper, there as

chief witness against the teenager, doubled as the court security officer.

And behind a battered wooden desk was Justice Gori. Fleshy, with eyes that water

at sentimental moments, he was wearing an open brown shirt, his T-shirt visible

at the neck.

The court computer that he bought with his own money was at home; it took him

two months to figure out how to turn the thing on, he said. He had no judge’s

robe. They are too expensive, he said. His judicial salary is $3,750 a year.

“There are certain things that are lacking,” he said.

He moved to Duane, population 159, from Saratoga County in his 40’s after a

divorce, enticed by the chance to hunt with his dogs.

“Maybe it’s the solitude,” said Justice Gori, who has since remarried. “You get

up here at night, when the highway quiets down, you don’t hear anything.”

Yet people cross paths in Franklin County in unlikely and sometimes volatile

ways: Mohawk Indians, the owners of lavish new vacation homes, Adirondack

tourists and fishermen, and others who cross the border on less savory business.

Drugs and domestic violence seem to be on the rise, and state prisons are big

employers.

When Justice Gori moved here about 20 years ago, the prison construction boom

offered jobs. After years as a dog trainer, “I picked up my tools and went back

to the bricklaying, mason trade,” he said.

Like a lot of newcomers to small towns, he wanted to get involved. But he didn’t

like the sight of blood, so that ruled out volunteer firefighting. He was

attracted instead to the court in the weathered firehouse. “Law has always been

kind of an interesting thing to me,” he said.

That interest, however, does not include a fascination with the technicalities

that occupy lawyers. “If you look at the laws, it’s all common sense,” he said.

Most of his work, since his first election in 1997, has been traffic cases. If

there were many serious crimes in Duane, he said, they may have gone unnoticed

out in the vast Adirondack nights. “Either we’re a nice, quiet town or two

people duked it out and one won and one lost, they got up and shook hands and

nobody knows about it,” he said.

There have been a handful of serious cases, the first phases of some felony

prosecutions. Once, state troopers tracked him down on a bricklaying job. They

said a local man was growing marijuana, and wanted a warrant to search his

property. In the dust and cement, it fell to William Gori, dog trainer and

mason, to put aside his tools and measure the rights guaranteed under the

Constitution. “I sat down,” he said. “Read everything. Looked at all the

pictures.” The troopers got their warrant.

In the makeshift courtroom on this winter night, he was warmly sympathetic to a

woman who had forgotten to put the registration sticker on her windshield. Case

dismissed.

But the teenager with the speeding tickets saw the stern Justice Gori. The boy

had tickets in a half-dozen Franklin County towns, and his lawyer proposed

combining the cases in another court.

No way. “What happens in the town of Duane,” Justice Gori declared, “stays in

the town of Duane.”

That is not always true. The other case that drew the attention of the

Commission on Judicial Conduct involved Lucille K. Millett, a Mohawk woman from

the reservation that straddles the county’s border with Canada. She was outside

the Duane court one night in 2004 waiting for her sister, whom she had driven

there for a traffic case. Justice Gori summoned Ms. Millett inside, asked for

her driver’s license and called the state police to run it through their

computer.

In an interview, Ms. Millett said she was frightened and embarrassed; no one

else was asked for a license. The only sense the sisters could make of it, she

said, was that they were the only American Indians in court.

She filed a complaint with the commission, which ruled last year that Justice

Gori had no right to demand anything of someone outside his court who faced no

charges.

Asked about the case, Justice Gori denied that he harbored any prejudice. He

said he thought he was acting within his authority.

“You learn by mistakes,” he said. “They say this is improper, I don’t do it

again.”

It is a measure of his isolation that his disciplinary hearings have been among

the few times he has had a chance to rub shoulders with the larger legal world.

He attends the refresher course each year. But he said the town could not afford

to send him to the annual state magistrates’ convention, held last year in

Niagara Falls, nor could he pay for the trip himself.

Still, he is convinced that he and the other justices across New York are honest

people trying to do right. “Economicswise,” he added, “you couldn’t get the job

done any cheaper.”

A County at the Edges

The troubles of Mr. Gori and his fellow justices are nothing new. In 1973, the

State Commission of Investigation arrived in the Franklin County village of

Saranac Lake to examine the work of one justice, a maintenance worker and

vacuum-cleaner salesman, whose “inept and mangled handling,” it said, had

bungled a felony grand larceny case.

What investigators found alarmed them. Money was missing. Records were sloppy. A

pile of cash from fines sat in an unlocked drawer. The justice’s relationship

with the police seemed far too close, and one of his law books was 44 years old.

Astonished, the investigators widened their inquiry to include all the justice

courts in the county and then expanded it across New York. Calling for statewide

reform, they concluded that “such deficiencies and ineptitude” in the justice

courts “simply must not be tolerated.”

But little seems to have changed in Franklin County’s justice courts since then.

Last November, one longtime village justice, Roy H. Kristoffersen, a salesman,

resigned after officials began investigating charges, which he denied, that he

“rendered favorable dispositions” for the son of the other village justice — in

Saranac Lake, the same place that touched off the investigation 33 years ago.

Another justice, Marie A. Cook, a school-bus driver who is still on the town

bench in Chateaugay, not only fixed a speeding ticket at the request of a fellow

justice, but she was so oblivious to ethical rules, the commission said last

fall, that she made an official record of the fix: “Reduced in the interest of

Justice Danny LaClair.”

Yet another, the town justice who released a rape suspect on bail as a favor to

a friend, tried to explain things to the commission: “Maybe you are not familiar

with what goes on in the North Country, but we are all more or less friends up

there.”

Such cases may only hint at the dimensions of the problem in Franklin’s courts.

A review for this article of rarely seen appeals files in Franklin County Court

showed a disturbing trail of legal blunders and judicial ignorance over the last

five years.

One justice seemed not to fully understand that criminal charges must be proved

beyond a reasonable doubt, wrote the county court judge, Robert G. Main Jr.

Another justice skipped over the matter of the constitutional guarantee of a

lawyer. Immediately after a woman charged with fraud said she could not afford

an attorney, Judge Main said, the village justice took her guilty plea instead

of appointing a lawyer.

Such problems are hardly news to many lawyers who make the rounds of Franklin

County’s justice courts. Some say they avoid the courts because the justices

often have trouble following their arguments.

In a place as poor and remote as Franklin County, the failings of modest courts

can loom large. Cases too minor to draw much interest from the rest of the legal

system — evictions, misdemeanor charges, disputes between neighbors, driving

infractions and applications for bail — come with real consequences for

small-town residents who may have little money or access to a lawyer.

Alexander Lesyk, the Franklin County public defender for 15 years until a few

months ago, said that while he had some successes for poor clients before local

justices, “I don’t believe any of them has enough training to handle a trial, to

handle constitutional issues, to stand up to and control an attorney on either

side when they need to.”

But challenging a justice can be bad for business, some lawyers said.

The district attorney, Mr. Champagne, said that when his office hears about

justices who stray from the law, it has to be careful. “We’re not going to get

into a confrontation with a judge we may have to go in front of next week on a

very serious preliminary hearing in a murder case,” he said.

A Case of Confusion

When Gary Betters got the letter from Justice Gori in March 1999 saying that his

claim for back pay had been dismissed, he was very confused. The message was a

single paragraph, and garbled at that. Even the date on it was wrong.

But that was only the start of his troubles.

He wrote to Justice Gori, asking for a mistrial. The justice never replied.

Mr. Betters decided to appeal in county court. But he could not persuade any

lawyer to take the case; several, he said, told him it would not be in their

interest to take on a town justice.

On his own, Mr. Betters filed a complaint with the Commission on Judicial

Conduct, and the truth emerged: The commission’s investigators discovered that

Justice Gori had gone to the Malone village offices before the trial and

interviewed the defense’s chief witness, the village treasurer, who told him

that Mr. Betters was owed nothing.

Justice Gori told the village attorney that he need not show up for the trial

because he had already decided to dismiss the case. The attorney was amazed. “A

lot of bells and whistles went off,” he told the commission.

But when Justice Gori explained himself to the commission in a closed hearing,

he said he had never heard of the rule against contacting one side of a case to

discuss the evidence. Further, the commission’s lawyer argued, a legal motion

filed by the village had completely bewildered Justice Gori, even after he made

several calls to the state’s help line for town justices.

“The whole concept I didn’t understand,” Justice Gori testified.

It was a damaging admission, but nothing compared with the case made by his own

lawyer, John A. Piasecki. He said his client’s error-riddled handling of Mr.

Betters’s suit was an indictment of the system, which put laymen on the bench,

gave them little training and left them to interpret the law.

Mr. Piasecki asked whether the state had ever checked Justice Gori’s reading

comprehension. (It had not.) He even tried to cross-examine the Malone village

attorney to show what he argued was the obvious difference between Justice Gori

and someone who actually understood the law.

Mr. Piasecki, a Franklin County lawyer himself, urged a “long-overdue

correction” for the justice court system, which he said “undermines confidence

in the integrity of the judiciary.”

The commission was not moved. Justice Gori, it said, had a duty to learn the

law. “Town justices wield enormous power in civil and criminal cases,” the

commission said, “and it is not unreasonable to expect them to know and follow

basic statutory procedures.”

Yet Justice Gori received the lightest public penalty the commission can issue,

an admonition.

As for Mr. Betters, he never found a lawyer to take his appeal. Today, he still

feels that his education in Franklin County law cost him a lot more than

$1,588.60.

“It broke down my belief in the justice system,” he said.

Business as Usual

The judicial career of William Gori began humbly enough.

“Nobody was jumping out of the woodwork wanting this job,” said Justice Gori,

who raised his hand for the position in 1997 after the sitting justice announced

his retirement.

With no opposition, he won the endorsement of the Republicans and then the

Democrats in Duane. The Republican chairwoman, Pamela M. LeMieux, said he

impressed party leaders as responsible and “very strict.”

In the general election, his only opponent was Gary Anderson, a former

accountant who ran as the candidate of what he named the Pine Tree Party.

“Nobody wants the job,” Mr. Anderson said.

Even the campaign was not especially interesting, Justice Gori recalled. “All I

said was: ‘I’m Bill Gori. I’m running for town justice and I’m only interested

in doing a good job for the town.’ ” He won, 64 to 39.

If the process was not a model of meticulous judicial selection, that fact may

carry an extra punch in Duane. The town, as it happens, was named for its

founders, descendants of the first federal judge in New York.

When President George Washington selected the judge, James Duane, a prominent

lawyer, for the post in 1789, he used the nomination to lay out his aspirations

for selecting judges in a democracy. The choice of who would sit on a nation’s

courts was a matter of “the first magnitude,” Washington wrote, and the

judiciary was “the pillar on which our political fabric must rest.”

Today, that fabric is a little frayed in Franklin County.

Thomas Catillaz, a former mayor of Saranac Lake, said that when political

parties there find a nominee, “It’s usually, ‘Thank God somebody’s running,’ ”

he said. “And if you’re in there, you’re in there for 20 years.”

When justices are publicly disciplined, that is often the end of the matter. As

Justice Gori recalls it, when he received his second admonition last year, the

local newspaper in Malone “put it way in the back.”

He faced an election after each ruling, but no opponent. Gary Cring, a retired

schoolteacher who has lived in Duane for six years, said he had not heard that

Justice Gori had been disciplined. Had that been better known, he said, voters

might have been less enthusiastic about re-electing him. “People figure he must

be doing a good job,” Mr. Cring said.

But Mrs. LeMieux, the Republican chairwoman, said it was not the town’s job to

police its justice. “If he did something that was that serious, I figure the

court system wouldn’t have allowed him to remain a justice,” she said. “If they

didn’t throw him out, then who are we to judge?”

And so Justice Gori is working his way through a third four-year term, learning

the job as he goes. He does not appear to share his lawyer’s disdain for how the

justice courts are run.

“I really feel the justice courts are the courts closest to the people,” he

said, and being a lawyer might interfere with that. “At times, lawyers get hung

up in certain things, so that maybe you wouldn’t get true justice in certain

cases.”

But a state police report from last year suggested that in Duane, true justice —

and empathy for the people — might be works in progress.

It seems that Brandon L. Lucas, a scrawny 19-year-old from the next county, was

trying to pay a ticket he had received in Duane for fishing with the wrong kind

of bait. Since the firehouse court was empty, as it often is, Mr. Lucas went

down the road to Justice Gori’s house.

Soon, Mr. Lucas was in the back of a state trooper’s car in handcuffs, and in

tears. An angry Justice Gori had berated him and called the police, the young

man recalled when a reporter tracked him down. He had evidently not seen the

sign on the judge’s garage: “If you proceed past this point, you are subject to

various trespass rules and regulations.”

The district attorney decided not to prosecute. And Mr. Lucas made his own

decision about wandering into the jurisdiction of Duane Town Court: Don’t.

“I’ll never go fishing up there again,” he said.

Delivering Small-Town Justice With a Mix of Trial and Error, NYT, 26.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/26/nyregion/26courts.html?hp&ex=1159329600&en=858c1bfeab1815d5&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Broken Bench

In Tiny Courts of New York, Abuses of Law

and Power

September 25, 2006

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GLABERSON

Some of the courtrooms are not even

courtrooms: tiny offices or basement rooms without a judge’s bench or jury box.

Sometimes the public is not admitted, witnesses are not sworn to tell the truth,

and there is no word-for-word record of the proceedings.

Nearly three-quarters of the judges are not lawyers, and many — truck drivers,

sewer workers or laborers — have scant grasp of the most basic legal principles.

Some never got through high school, and at least one went no further than grade

school.

But serious things happen in these little rooms all over New York State. People

have been sent to jail without a guilty plea or a trial, or tossed from their

homes without a proper proceeding. In violation of the law, defendants have been

refused lawyers, or sentenced to weeks in jail because they cannot pay a fine.

Frightened women have been denied protection from abuse.

These are New York’s town and village courts, or justice courts, as the 1,250 of

them are widely known. In the public imagination, they are quaint holdovers from

a bygone era, handling nothing weightier than traffic tickets and small claims.

They get a roll of the eyes from lawyers who amuse one another with tales of

incompetent small-town justices.

A woman in Malone, N.Y., was not amused. A mother of four, she went to court in

that North Country village seeking an order of protection against her husband,

who the police said had choked her, kicked her in the stomach and threatened to

kill her. The justice, Donald R. Roberts, a former state trooper with a high

school diploma, not only refused, according to state officials, but later told

the court clerk, “Every woman needs a good pounding every now and then.”

A black soldier charged in a bar fight near Fort Drum became alarmed when his

accuser described him in court as “that colored man.” But the village justice,

Charles A. Pennington, a boat hauler and a high school graduate, denied his

objections and later convicted him. “You know,” the justice said, “I could

understand if he would have called you a Negro, or he had called you a nigger.”

And several people in the small town of Dannemora were intimidated by their

longtime justice, Thomas R. Buckley, a phone-company repairman who cursed at

defendants and jailed them without bail or a trial, state disciplinary officials

found. Feuding with a neighbor over her dog’s running loose, he threatened to

jail her and ordered the dog killed.

“I just follow my own common sense,” Mr. Buckley, in an interview, said of his

13 years on the bench. “And the hell with the law.”

The New York Times spent a year examining the life and history of this largely

hidden world, a constellation of 1,971 part-time justices, from the suburbs of

New York City to the farm towns near Niagara Falls.

It is impossible to say just how many of those justices are ill-informed or

abusive. Officially a part of the state court system, yet financed by the towns

and villages, the justice courts are essentially unsupervised by either. State

court officials know little about the justices, and cannot reliably say how many

cases they handle or how many are appealed. Even the agency charged with

disciplining them, the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, is not equipped to

fully police their vast numbers.

But The Times reviewed public documents dating back decades and, unannounced,

visited courts in every part of the state. It examined records of closed

disciplinary hearings. It tracked down defendants, and interviewed prosecutors

and defense lawyers, plaintiffs and bystanders.

The examination found overwhelming evidence that decade after decade and up to

this day, people have often been denied fundamental legal rights. Defendants

have been jailed illegally. Others have been subjected to racial and sexual

bigotry so explicit it seems to come from some other place and time. People have

been denied the right to a trial, an impartial judge and the presumption of

innocence.

In 2003 alone, justices disciplined by the state included one in Montgomery

County who had closed his court to the public and let prosecutors run the

proceedings during 20 years in office. Another, in Westchester County, had

warned the police not to arrest his political cronies for drunken driving, and

asked a Lebanese-American with a parking ticket if she was a terrorist. A third,

in Delaware County, had been convicted of having sex with a mentally retarded

woman in his care.

New York is one of about 30 states that still rely on these kinds of local

judges, descendants of the justices who kept the peace in Colonial days, when

lawyers were scarce. Many states, alarmed by mistakes and abuse, have moved in

recent decades to rein in their authority or require more training. Some, from

Delaware to California, have overhauled the courts, scrapped them entirely or

required that local judges be lawyers.

But New York has no such requirement. It demands more schooling for licensed

manicurists and hair stylists.

And it has left its justices with the same powers — more than in many states —

even though governors, blue-ribbon commissions and others have been denouncing

the courts as outdated and unjust since as far back as 1908, when a justice in

Westchester County set up a roadside speed trap, fining drivers for whatever

cash they were carrying.

Nearly a century later, a 76-year-old Elmira man who contested a speeding ticket

in Newfield, outside Ithaca, was jailed without even a warning for three days in

2003 because he called the sheriff’s deputy a liar.

“I thought, this is not America,” said the man, Michael J. Pronti, who spent

another two years and $8,000 before a state appeals court ruled that he had been

improperly jailed.

‘Justice in the Dark’

It is tempting to view the justice courts as weak and inconsequential because

the bulk of their business is traffic violations. Yet among their 2.2 million

cases, the courts handle more than 300,000 criminal matters a year. Justices can

impose jail sentences of up to two years. Even in the smallest cases, some have

wielded powers and punishments far beyond what the law allows.

The reason is plain: Many do not know or seem to care what the law is. Justices

are not screened for competence, temperament or even reading ability. The only

requirement is that they be elected. But voters often have little inkling of the

justices’ power or their sometimes tainted records.

For the nearly 75 percent of justices who are not lawyers, the only initial

training is six days of state-administered classes, followed by a true-or-false

test so rudimentary that the official who runs it said only one candidate since

1999 had failed. A sample question for the justices: “Town and village justices

must maintain dignity, order and decorum in their courtrooms” — true or false?

The result, records and interviews show, is a second-class system of justice.

The first class — the city, county and higher courts — is familiar to anyone who

has served on a jury or watched “Law & Order”: hardly perfect, but a place of

law-schooled judges, support staffs and strict rules. The lower and far larger

rung of town and village courts relies on part-time justices, most of them

poorly paid, some without a single clerk. Those justices — two-thirds of all the

state’s judges — are not required to make transcripts or tape recordings of what

goes on, so it is often difficult to appeal their decisions.

When they stray badly, the Commission on Judicial Conduct — a panel of lawyers,

judges and others — can do little more than try to contain the damage.

Some 1,140 justices have received some sort of reprimand over the last three

decades — an average of about 40 a year, either privately warned, publicly

rebuked or removed. They are seriously disciplined at a steeper rate than their

higher-court colleagues.

The Office of Court Administration, which runs the state court system, makes

little pretense of knowing much about what happens in the justice courts. Beyond

their names, ages and addresses, it has little information about the justices.

Because they are paid by the towns and loosely tied into the court system, “we

have limited administrative control, and very, very limited financial control,”

said Jan H. Plumadore, the deputy chief administrative judge for all courts

outside New York City.

The courts also handle money — more than $200 million a year in fines and fees.

But the state comptroller’s office, which once conducted scores of justice-court

audits every year, now does only a handful. When it looked most recently,

auditing a dozen courts in May, it reported serious financial-management

problems and estimated that millions of dollars a year might be missing from the

justice courts statewide.

Norman P. Effman has been the public defender for 16 years in Wyoming County,

where he said only one of the 37 justices was a lawyer. In testimony last year,

he described the justice courts as a forgotten realm: a “closed door, back of

someone’s house, in the barn, in the highway department, no record” justice

system.

“The reality is,” he told a state commission, “if you keep justice in the dark,

it stays in the dark.”

That commission, which was studying how the court system treats poor people,

issued a study in June saying the justice courts remained “a fractured and

flawed system.” And in recent days, the Office of Court Administration has said

it plans to begin addressing some of those failings — for instance, taking steps

to double the amount of initial training and to ensure that proceedings are

recorded.

But those measures do not address some of the most serious problems: the use of

justices who are not lawyers, and the state’s weak oversight.

This is not the first time the justice courts have come under scrutiny.

“Probably the most unsatisfactory feature of the administration of criminal law

remaining in the state today is the obsolete and antiquated institution known as

the justice of the peace,” another state commission concluded.

The year was 1927.

A Record of Trouble

Certainly, there are worthy justices, and defenders of the system say the good

far outnumber the bad. Those supporters, chiefly the justices themselves and the

local political leaders who often select them, contend that hometown judges know

the hometown problems — and the problem people — and can tailor common-sense

solutions.

And, they have argued, that putting lawyers in charge of all the courts could

cost the state tens of millions of dollars.

“It is the most efficient, low-cost method of ensuring that the people of the

state receive justice,” said Thomas R. Dias, a town justice in Columbia County

who is president of the State Magistrates Association, the justices’

organization.

But the record shows otherwise in hundreds of disciplinary cases — most of them

unknown to the public.

In the Catskills, Stanley Yusko routinely jailed people awaiting trial for

longer than the law allows — in one case for 64 days because he thought the

defendant had information about vandalism at the justice’s own home, said state

officials, who removed him as Coxsackie village justice in 1995. Mr. Yusko was

not even supposed to be a justice; he had actually failed the true-or-false

test.

Outside Rochester, in Le Roy, a justice who is still in office concocted false

statements, state officials said, to help immigration officials deport a

Hispanic migrant worker in 2003. Although the man had pleaded not guilty to

trespassing, the town justice, Charles E. Dusen, issued a court order saying he

had been convicted. In an interview, Justice Dusen said he tried to right his

wrong after the worker’s lawyer complained. But the man was still deported.

Last December, disciplinary officials disclosed that in a five-year period, a

Rochester-area justice had mistakenly imposed $170,000 in traffic fines beyond

what the law allowed. And in June, a justice in western New York was disciplined

for threatening to jail a man — and warning him to “bring a couple thousand in

bail money” — over a complaining phone message the man had left him.

Even the commuter towns around New York City, where the justices are typically

lawyers, have endured the system’s abuses.

In Mount Kisco, people who asked for the court’s sympathy were treated to

sarcasm: Justice Joseph J. Cerbone would pull out a nine-inch violin and

threaten to play. Mr. Cerbone phoned one woman and talked her out of pressing

abuse charges against the son of former clients, state records show. But it took

eight years, and evidence that he had taken money from an escrow account, before

the State Court of Appeals removed him in 2004 after a quarter-century in

office.

In interviews, many of these justices disputed the findings against them, saying

the Commission on Judicial Conduct was unfair and determined to end the justice

courts.

Commission officials say they have no such agenda.

And the agency is struggling itself. Charged with policing all the state’s

courts, it can do no more than respond to complaints. Its staff has shrunk by

more than half in the last two decades, with just two investigators for the

western half of the state.

So commission officials were surprised to learn last year that a western New

York justice who had resigned while facing disciplinary charges was back on the

bench.

The commission twice disciplined the town justice, Paul F. Bender of Marion, for

deriding women in abuse cases. Arraigning one man on assault charges, he asked

the police investigator whether the case was “just a Saturday night brawl where

he smacks her and she wants him back in the morning.”

But the commission spared him removal in 1999 because he was not seeking

re-election. Four years later Mr. Bender ran again anyway, unbeknown to the

commission, for a term that will not expire until 2007.

Robert H. Tembeckjian, the commission’s administrator, said, “Our working

assumption is, a judge who resigns while under disciplinary charges by the

commission is not going to return to the bench.” But he would not say whether

his agency would — or could — take any action against Justice Bender.

‘I’m Not a Lawyer’

A 17-year-old girl had stayed out all night, then fought with her family and

wound up facing a harassment charge in court in Alexandria Bay, a busy tourist

village on the St. Lawrence River. The justice, Charles A. Pennington, a boat

hauler with 23 years on the bench, took her not-guilty plea on a Sunday in 2003.

But when told that the girl had no place to go, the judge did not send her to a

women’s shelter or alert social service officials, as local justices typically

do. He took her home.

“I left the court kind of in shock,” a police officer later testified. “I’ve

never heard of anything like this before.”

The girl’s mother, Keitha Rogers, said in an interview that she was appalled to

find her daughter at the home of the justice, then 61, as he sat drinking with

another man. “Sure, he can tell the difference between the stern and the bow,”

Ms. Rogers said. “But what does that have to do with making major judgments

about people’s lives?”

The judicial conduct commission, which ordered Justice Pennington’s removal last

fall for this and other lapses, ruled that while there was no evidence he had

made any improper advances toward the girl, who left after about an hour, he had

shown “extraordinarily poor judgment.”

And while Mr. Pennington argued that he had not been drinking, he did not

entirely disagree with the findings. “Granted, there is mistakes,” said the

justice, who resigned before the commission ruled. “I’m not a lawyer.”

Neither are most of his peers. And that is pretty much all the state knows about

them. Office of Court Administration officials say the only way they usually

find out a new justice has been elected is if local officials notify them.

For decades, the agency has asked justices to fill out modest biographical

questionnaires, then filed away the answers. Under freedom of information law,

The Times obtained questionnaires completed by more than 1,800 current justices;

they portray a group that is often poorly educated and poorly paid, even though

the law they are dealing with is increasingly complex.

Of those who are not lawyers, about a third — more than 400 — had no formal

education beyond high school. At least 40 did not complete high school, though

several went on to earn equivalency degrees.

Interviews with more than 60 justices made it clearer who many of these people

are: retirees, farmers, mechanics, former police officers and others with

flexible schedules or seasonal work. Most look something like Mr. Pennington:

white, and graying. At least 30 justices are in their 80’s, well beyond the

mandatory retirement age, 70, for other New York judges.

Though the justices’ pay is often meager — as little as $850 a year — they can

set bail, a basic legal safeguard. They hold crucial preliminary hearings in

felony cases and conduct trials on misdemeanors. They preside over civil cases

with claims of up to $3,000, and landlord-tenant disputes with no dollar limit,

including commercial cases involving hundreds of thousands of dollars.

And then there are the powers they simply take.

In what the Commission on Judicial Conduct called “a shocking abuse of judicial

power,” Justice Roger C. Maclaughlin single-handedly went after a man he decided

was violating local codes on the keeping of livestock in Steuben, near Utica.

The justice interviewed witnesses, tipped off the code-enforcement officer,

lobbied the town board to deny the man approval to run a trailer park, then

jailed him for 10 days without bail — or even a chance to defend himself, the

commission said.

In an interview, Justice Maclaughlin said the commission seemed to be chasing

legal technicalities rather than real justice.

An Essex County town justice, Richard H. Rock, jailed two 16-year-olds overnight

without a trial, saying he wanted “to teach them a lesson.” They had been

accused of spitting at two other people and charged with harassment. Then he

sent them back for another 10 days, the commission said, without ever advising

them they had a right to a lawyer.

In 2001, the commission punished him and Justice Maclaughlin with censure, the

most serious penalty short of removal from the bench. Justice Maclaughlin is now

in his 11th year in office. Justice Rock is in his 10th.

In Alexandria Bay, where Justice Pennington presided at a metal desk in a tiny

room inside the police building, a quarter-century in office did not seem to

deepen his understanding of his role. Just three days after he took home the

17-year-old girl, another case raised fresh questions about his familiarity with

the law, or even the world outside his court.

Eeric D. Bailey, a 21-year-old black soldier from nearby Fort Drum, was facing a

disorderly conduct charge after a tussle with a white bar bouncer. Sitting three

feet from Mr. Bailey, the bouncer identified him as “that colored man.” Mr.

Bailey’s jaw dropped.

The soldier, who did not have a lawyer, told the judge that the term was

offensive. But Justice Pennington said that while certain other words were

racist, “colored” was not. “For years we had no colored people here,” he said.

The commission had heard worse. After arraigning three black defendants arrested

in a college disturbance in 1994, a justice in the Finger Lakes region said in

court, “Oh, it’s been a rough day — all those blacks in here.” A few years

before that, a Catskill justice reminisced in court that it was safe for young

women to walk around “before the blacks and Puerto Ricans moved here.”

In an interview, Justice Pennington said the commission had treated him

unfairly. But he may not have helped his case when he told the commission that

“colored” was an acceptable description.

“I mean, to me,” he testified, “colored doesn’t preferably mean black. It could

be an Indian, who’s red. It could be Chinese, who’s considered yellow.”

Basic Training

As the blunders, and worse, have piled up over the years, so have the muffled

complaints from within the system. Transcripts of the commission’s disciplinary

hearings, which are usually closed to the public, show that some justices have

nearly begged for more training, or any kind of help.

Anthony Ellis, a meat cutter who routinely jailed defendants in Tupper Lake to

coerce them into pleading guilty, neatly summed up his insecurities in one

closed hearing: “I’m almost like a pilot flying by the seat of my pants.”

William G. Mayville, a retired factory worker who turned his courtroom in nearby

Fort Covington into a collection agency for local business owners, offered a

quietly damning explanation: “I certainly am only a simple man doing a job that,

you know, the very best I can do with a limited amount of education that they

offered me.”

Simple men, and their simple wisdom, are the whole idea behind the justice

courts. A 13th-century English institution, the justice of the peace was

imported to the colonies in the 1600’s along with a fundamental notion: that

laymen could settle small-bore cases with practical solutions grounded in local

custom or common sense.

But as life, and the law, had become vastly more complex by the mid-20th

century, several states, including California, New Jersey and Connecticut,

created more professional local courts.

In Delaware, where the appointed local magistrates have less authority than New

York’s justices, the state screens candidates with academic and psychological

tests, and starts them off with 11 weeks of training. “It is a reflection of the

view that when we’re dealing with people’s livelihood, when we’re dealing with

people’s freedom, we’re going to take this seriously,” said the chief

magistrate, Alan G. Davis, a lawyer.

In New York, the justice courts have been replaced by state-financed district

courts, with lawyer judges, in Nassau County and western Suffolk County. But the

last major calls for statewide reform sputtered out in the early 1980’s, and the

amount of training for justices has not changed. Those without law degrees must

take six days of classes at the start. Lawyers do not have to attend, but all

justices must take a 12-hour refresher course once a year.

Maryrita Dobiel, who runs the training program for the Office of Court

Administration, said the classes provide an introduction to legal principles,

but not much more, given a student body with such varying levels of education.

“We have to teach to the lowest common denominator,” she said. General

principles of criminal law, a subject that takes up a semester or more in law

school, gets about five hours.

At training’s end, justices must score at least 70 percent on a test of 50

questions, all true or false. Those who fail can retake the course, and the

test. “We don’t decide whether they’re qualified to be a judge,” Ms. Dobiel

said. “The people who have elected them have already made that decision.”

The real test comes on the bench.

Several justices have threatened to arrest litigants in small-claims cases,

showing they do not understand the difference between civil and criminal cases.

Others have told the judicial conduct commission that they disagreed with the

constitutional guarantee that a defendant is entitled to a lawyer.

John D. Cox, a quarry manager in Le Ray, near Watertown, summarily jailed people

who were unable to pay fines, the commission said. But he received the lightest

public penalty, an admonition, in 2002 after he explained that in 22 years in

office, he had never been taught that state law allows defendants a new hearing

and a lawyer when they say they cannot pay their fine.

The justices do have something of a lifeline: They can call a resource center

near Albany where four lawyers field more than 18,000 questions a year. But

there are limits on what the center tries to do.

“We tell them what their options are,” said the center’s supervisor, Paul

Toomey. “We don’t tell them they’re wrong.”

Power and Prejudice

Few people who came to his court ever told Donald R. Roberts he was wrong. A

strapping former state trooper, he was working as a gas-company truck driver

when he was appointed village justice in Malone, near the Canadian border, in

1993. When he was removed five years later, the Commission on Judicial Conduct

dispatched him with a stinging description: “a biased, mean-spirited, bullying

judge.”

It was Justice Roberts who declared that women needed “a good pounding.” He had

already battled with the county district attorney over his resistance to

granting orders of protection.

When a village resident asked that the dentist suing him be forced to come to

court to prove his case, Justice Roberts told the man, who had a Hispanic

surname: “You’re not from around here, and that’s not the way we do things

around here.” The justice did not mention that the plaintiff was his own

dentist.

A common argument in favor of New York’s justice courts is that local judges

know the people and problems that come before them. But that can be a problem

itself when justices use those prejudices to favor friends and ride herd over

others.

“They have their own little fiefdoms,” said Laurie Shanks, an Albany Law School

professor. “Some are benevolent despots, but despots nonetheless.”

Again and again, the commission’s records show, justices have failed to remove

themselves from cases involving their own families.

In this department, Pamela L. Kadur may hold a record. As town justice in Root,

west of Schenectady, she presided over at least seven cases involving relatives,

who often received lenient treatment, the commission said when it ordered her

removal in 2003. Justice Kadur heard a speeding case against her son in her own

kitchen, then tried to cover up their family relationship in record books, the

commission said, by misspelling his last name.

One longtime town justice near Albany let a friend who owned a driving school

sit with him at the bench; when the justice ordered anyone to take a

driver-training course, only the friend’s school was acceptable. Another

justice, in Rensselaer County, told a trucker charged with drunken driving that

he would not suspend his license because “I can’t do that to a fellow truck

driver.”

Historically, large numbers of the justices have been former law enforcement

officers, and lawyers complain that many have unfairly favored the police and

prosecutors.

Some justices, unsure of the law, have also come to rely too much on the

authorities. Elaine M. Rider, who presided in Waterville, near Utica, fretted

that she did not “really have the time to puzzle this out” when a criminal

defendant argued that evidence had been seized illegally. So she had the

prosecutor write her decision, the commission said.

But one of the most common prejudices on view in the commission’s files is far

more basic, and it can be found as often in the big-city suburbs that have

official-looking courthouses and lawyers on the bench.

In 20 years in office in Haverstraw, north of New York City in Rockland County,

Justice Ralph T. Romano drew attention for his opinions on women, state files

show. Arraigning a man in 1997 on charges that he had hit his wife in the face

with a telephone, he laughed and asked, “What was wrong with this?” Arraigning a

woman on charges that she had sexually abused a 12-year-old boy, the justice

asked his courtroom, “Where were girls like this when I was 12?”

Across the Hudson, Joseph Cerbone, the Mount Kisco justice with the miniature

violin, persuaded a young woman to drop her abuse case against the son of a

couple he had done legal work for. She told the commission that while she did

not believe the justice’s claim that the son was “a decent guy” who had “made a

mistake,” she had no choice.

“I kind of felt I had no one behind me, no support,” she said. “And by getting a

phone call from a judge, I felt that maybe I was making a mistake by going

through with these charges.”

But the human damage can be much worse in the small communities where the

justice is often the most powerful local official.

In 11 years as justice in Dannemora, in the North Country, Thomas R. Buckley had

his own special treatment for defendants without much money: Even if they were

found not guilty, he ordered them to perform community service work to pay for

their court-appointed lawyers, although defense lawyers and the district

attorney had reminded him for years that the law guaranteed a lawyer at no cost.

“The only unconstitutional part,” he told the commission before it removed him

in 2000, “is for these freeloaders to expect a free ride.”

He twice jailed David Velie, a 19-year-old charged with a misdemeanor, even

though the law required him to set bail. In an interview, Mr. Buckley explained

that the young man had been a troublemaker “ever since he was born.”

Like many small-town justices, he said many of his decisions were down-to-earth

solutions. “You’ve got to use your own judgment,” he said. “That’s why they call

us judges. The law is not always right.”

Some residents say that without the law to protect them, they lived in fear.

Debra E. Bordeau, the justice’s neighbor, said she went into hiding after he

threatened to jail her in a dispute over her dog, which he ordered destroyed.

And Carson F. Arnold Sr., a contractor from a nearby town, was jailed for five

days after a woman who knew Justice Buckley complained that Mr. Arnold had

threatened her, the commission said. There was no trial. The justice simply told

Mr. Arnold to shut up, then sentenced him without bail.

“How many years did he treat people like this?” Mr. Arnold asked in an

interview. “How many people did this affect?”

A Culture of Secrets

The feeling of powerlessness often begins at the courthouse door.

Many justices preside in intimidatingly tight quarters, admitting participants

one by one. Many have heard testimony, settled claims or ruled in criminal cases

without notifying the prosecutor, lawyers or even the people directly involved.

Some justices can be very selective, state records show: At a 1999 criminal

trial in Kinderhook, south of Albany, Justice Edward J. Williams admitted

everyone but the victim’s lawyer.

Court sessions may be just as unpredictable — held infrequently or at odd hours,

or canceled without notice. In 2004, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund found that people awaiting trial in Schuyler County in the Finger Lakes

were jailed for months simply waiting for court to convene again. A high school

student arrested on a minor drug charge in the summer of 2003, it said, was

still sitting in jail in October.

But the biggest obstacle of all is pinning down what happens in the courtrooms.

A Rochester poverty lawyer, Laurie Lambrix, said that when she appealed the case

of a mother of six — a black woman evicted in 1999 by a white landlord who she

said had made racist comments — a justice in nearby Gates told her she could not

examine the court file of her own client. “I knew court records were public

records,” Ms. Lambrix said. “I couldn’t believe a judge would be ignorant of

that.”

She was lucky; at least there were records, which she eventually obtained. In

many justice courts, it is next to impossible to reconstruct what happened. Some

towns spring for a stenographer or taping system, and some justices try to

scrawl notes while they preside. But in some cases, there are not even notes.