|

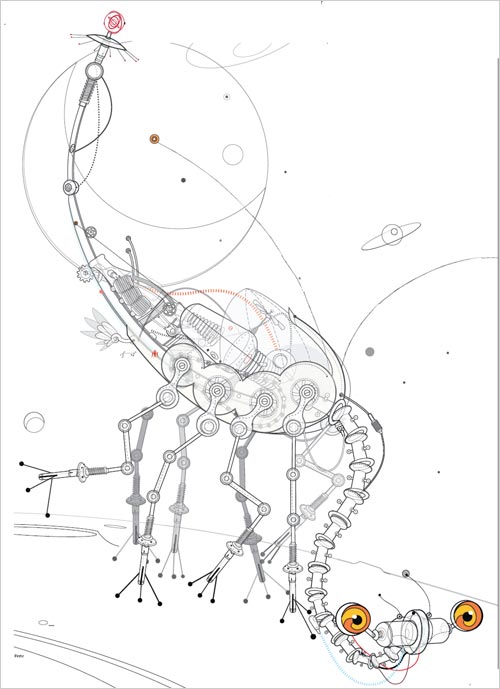

History > 2006 > USA > Space (I)

No, it's not an alien.

Engineers are

designing spacecraft that can think for themselves,

then execute their own commands,

without waiting for cues from ground

controllers.

Feric

Intelligent Beings in Space!

NYT 30.5.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/30/science/space/30rock.html

Intelligent Beings in Space!

May 30, 2006

The New York Times

By KENNETH CHANG

A future space mission to Titan, Saturn's intriguing moon

enveloped in clouds, might deploy a blimp to float around the thick atmosphere

and survey the sand dunes and carved valleys below.

But the blimp's ability to communicate would be limited. A message would take

about an hour and a half to travel more than 800 million miles to Earth, and any

response would take another hour and a half to get to Titan.

Three hours would be a long time to wait if the message were: "Help! I'm caught

in a downdraft. What do I do?" Or if the blimp were to spot something unusual —

an eruption of an ice volcano — it might have drifted away before it received

the command to take a closer look. The eruption may also have ended by then.

Until recently, interplanetary robotic explorers have largely been marionettes

of mission controllers back on Earth. The controllers sent instructions, and the

spacecraft diligently executed them.

But as missions go farther and become more ambitious, long-distance puppetry

becomes less and less practical. If dumb spacecraft will not work, the answer is

to make them smarter. Artificial intelligence will increasingly give spacecraft

the ability to think for themselves.

"These technologies are already in operation on specific missions," said Steve

Chien, a computer scientist who heads the artificial intelligence group at

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Scientists discussed some

of the recent progress last week at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union

in Baltimore.

HAL, the soulful conversationalist at the helm of the spaceship in "2001: A

Space Odyssey," is not on the drawing board. The work so far has been more along

the lines of Roomba, the robotic vacuum cleaner, with autonomy to perform

certain specific tasks.

Dr. Chien's group wrote the software that manages the schedule of Earth

Observing-1, a satellite that looks for natural disasters like volcanic

eruptions, wildfires and floods.

The satellite, known as E.O.-1 for short, takes repeated pictures of the areas

it watches, looking for changes that would indicate an eruption or other event.

Other satellites or sensors on the ground can also dispatch an alert to E.O.-1,

telling it of something it should look at.

"Almost immediately, within a matter of hours, the spacecraft is reprogramming

itself to image these targets," Dr. Chien said, "and we can get rapid response

imagery of breaking science events."

The spacecraft adds the new observation to its schedule and starts rearranging

its other tasks. An observation that had been planned may be canceled or moved.

All this occurs without a human in the loop. E.O.-1 just drops a note to the

operators about what it has done.

When E.O.-1 was launched in 2000, people on the ground did the satellite's

planning. The planning software was first tried in 2003, and the satellite now

uses it full time. That not only sped up its reaction time, but it also cut its

operating cost of $3.6 million a year by more than one-quarter.

Similar programming can be used for future planetary missions, perhaps for the

next visit to Jupiter and its moons, to detect volcanic eruptions on Io or a

shift in the fractures on the frozen surface of Europa.

NASA's two rovers now on Mars — the Spirit and the Opportunity — also possess a

measure of thinking ability. As they drive, the rovers use stereo cameras to

judge the distance and size of rocks in their paths in order to figure out how

to maneuver around obstacles.

"At every step, it looks at dozens of potential choices," said Mark W. Maimone,

a member of the team working on the rovers' software. "It picks the safest path

that gets it closer to its goal."

A software upgrade to be sent up to the rovers in a month or so will provide

even greater autonomy. Mission controllers will then be able to tell the rovers

simply, "Go to that rock and put your instrument arm down on it." Currently, arm

deployment takes an extra day, because controllers must first see the rover's

final position before issuing the command to lower the arm.

Another part of the upgrade, adapted from the E.O.-1 software, will enable the

rovers to perform a first cut of data, determining what is useful. The rovers

have been taking photographs to search for clouds and mini-tornadoes known as

dust devils. But through much of the Martian year, clouds and dust devils are

rare, so most of the photos show nothing, and beaming them all to Earth is a

waste of time.

"You're restricted in the number of images you can return," said Rebecca Castaño

of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

With the new software, the rovers will analyze the photos and send back only

those that appear to contain what the scientists are looking for. That will

allow wider and more frequent searches. Dr. Castaño said tests showed that the

software was correct in identifying clouds 93 percent of the time.

More important, the software rarely failed at finding a cloud when one was

there. Rather, the software sometimes saw a cloud when there was none — a

mistake that a scientist on the ground can easily correct.

Still, these spacecraft seem far from intelligent. E.O.-1's scheduling programs

are not that different from the software that Wal-Mart uses to manage inventory,

and the rovers' driving autonomy does not give them the ability to recognize

unanticipated traps. In April last year, the Opportunity blithely drove into a

sand dune, and took five weeks to back out.

"None of the A.I. systems are as smart as a 2-year-old," said Cynthia Y. Cheung,

a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "We want

this system to be able to learn and react to the environment."

Dr. Cheung is a member of a team led by Steven Curtis designing a more ambitious

rover. It does not have wheels. Instead, it looks like a shape-changing jungle

gym, with trusses that lengthen and shorten. A simple prototype has been built.

Computer animations illustrate its possibilities. Across flat terrain, it would

roll like tumbleweed.

It could pull itself, almost catlike, onto rocks or flatten itself and slither

through holes. (The animation can be viewed at nytimes.com/science.)

To achieve those abilities, the machine would need sensors to observe its

surroundings and then use the best mode of locomotion. While some safety rules

might be explicitly programmed — the equivalent of telling a child, "Do not

cross a busy road" — the scientists also will put in programming that allows the

robot to learn its behavior through trial and error.

"You'd essentially set up a playground where the robot can perform these simple

behaviors," said Michael Rilee, another member of the Goddard team. "It's a lot

like what children do when they're very small, and they're just learning to move

around."

Dr. Curtis said he thought the technology could be ready for a rover to explore

the rockier regions of the Moon in a few years.

How much new technology will be built and used is an unanswered question. "This

is a completely different way of doing business," Dr. Chien said. "People are

risk averse, for good reasons."

Interplanetary space probes cost hundreds of millions of dollars each, and a

mistake in the programming can lose the craft. An attempt last year to get a

small craft named DART, Demonstration of Autonomous Rendezvous Technology, to

dock autonomously with another satellite resulted instead in DART's collision

with the target.

Scientists are also wary about letting a spacecraft throw away information

before humans get to sift through it. They often joke about a rover obliviously

driving past a dinosaur bone lying on the Martian surface because it had been

programmed to recognize only rocks.

But autonomy will also allow them to do more at lower cost.

For some possible missions, like the Titan blimp, "This sort of thing is going

to be key for making the most of the mission," said Ralph D. Lorenz, a planetary

scientist at the University of Arizona.

"In an ideal world," he added, "you'd downlink every picture, and scientists

would have all of the time in the world to look over them, but you don't have

that luxury."

Because of the limited communications with Earth, Dr. Lorenz said the craft

might summarize its findings — that it has been flying over sand dunes, for

example — and send back only a few representative photos instead of images of

the entire landscape.

"To get the best science, you want to send down only the data with the richest

science concentration," Dr. Lorenz said.

And for that, Dr. Lorenz is willing to let the spacecraft do the choosing.

Intelligent Beings

in Space!, NYT, 30.5.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/30/science/space/30rock.html

States again ponder space travel business

Updated 5/14/2006 11:43 AM ET

By Alicia Chang, The Associated Press

USA Today

LOS ANGELES — The promise of blasting thrill-seeking

tourists into space is fueling an unprecedented rush to build snazzy commercial

spaceports.

The Federal Aviation Administration is reviewing proposals from New Mexico,

Oklahoma and Texas to be gateways for private space travel. Depending on how

environmental reviews and other requirements go, approval could come as early as

this year and the sites could begin preparing to ferry space tourists soon

afterward.

The current spaceport boom recalls the mid-1990s, when the first spaceport fad

generated hype but no real construction. Finally, technology may have caught up

with starry-eyed plans.

Aerospace designer Burt Rutan, who is building a commercial spaceship fleet for

British space tourism operator Virgin Galactic, recently expressed his amazement

at the flurry of proposals.

"It's almost humorous to watch the worldwide battle of the spaceports," Rutan

mused earlier this month at the International Space Development Conference.

For decades, spaceports have been used mostly by NASA and the Pentagon to rocket

astronauts and satellites into orbit.

Traditional launch ranges are often spartan mixes of lonely launch pad towers,

concrete runways and aircraft hangars. Many are located in remote coastal areas

— Florida's Cape Canaveral being the best known — so that debris won't hit

populated areas.

The current spaceport boom promises futuristic complexes that evoke the Jetsons.

But cashing in requires a gamble.

None of the private rockets under development has been test-flown. And even once

the FAA licenses any vehicles, the infant industry initially won't boast

multiple daily flights — at $100,000 to $250,000 a head, the market is decidedly

limited.

For states that invest early, however, the long-term economic benefits could be

substantial. A recent study commissioned by New Mexico predicted that its

proposed hub could net $750 million in revenue and up to 5,800 new jobs by 2020.

States with spaceports anchored by a reliable spaceliner and designed like a

galactic Disneyland also could be a magnet for high-skill, high-wage labor and

sprout cottage industries.

The rush to build commercial space hubs is spurred by entrepreneurs who want to

send rich passengers into suborbital space — a region about 60 miles above

Earth. Several will build their rockets this summer with tentative plans to fly

as early as next year pending regulatory approval.

New Mexico, which inked a deal with Virgin Galactic last year to construct a

$225 million spaceport on 27 square miles of desert, is expected to select a

winning architectural design from six entries on June 2.

While details of the spaceport designs are secret until a winner is chosen,

tentative plans call for a complex built mostly underground. The facility, which

would be funded by a mix of federal, state and local money, could open in late

2009. Virgin would have a 20-year lease on the facility.

Until then, Virgin Galactic, founded by British mogul Richard Branson, plans to

fly the first passengers from California's Mojave Airport, where the

Rutan-designed SpaceShipOne became the first privately manned rocketship to

reach space in 2004.

Outside the seven government-run launch ranges, the Mojave hosts one of five

non-federal licensed spaceports in the U.S. that serve both commercial and

government interests. The non-federal ports are either state or privately

operated.

Another space tourism operator, Rocketplane Kistler, wants to launch from the

Oklahoma Spaceport. Still pending FAA approval, that spaceport sits on the site

of the former Clinton-Sherman Airpark in Burns Flats and boasts one of the

world's longest runways.

The Oklahoma Spaceport has passed all its requirements and is expected to win an

FAA license over the next several weeks, said Bill Khourie, executive director

of the Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority.

Mission control is being upgraded and there are plans for VIP lounges and other

amenities.

"We ultimately plan on building more sexy facilities," said Charles Lauer, vice

president of business development at Rocketplane Kistler.

The FAA also is considering two proposed spaceports in Texas, including a

private spaceport on 165,000 acres of desolate ranch land about 120 miles east

of El Paso bought by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos. Bezos had said his space

tourism firm, Blue Origin, would first build basic structures, then begin flight

tests in six to seven years.

To gain a spaceport license, a facility must pass an environmental review and

prove that its location won't harm surrounding communities or the public, said

Patricia Grace Smith, associate administrator of the FAA Office of Commercial

Space Transportation. Spaceports and launch vehicles are licensed separately.

The 1990s saw a different spaceport race.

Back then, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas were among more than a dozen states

that squandered thousands of dollars trying to woo a much-hyped experimental

spacecraft program.

VentureStar, a wedge-shaped spaceship by NASA and Lockheed Martin, was supposed

to replace the space shuttle. But the program was plagued by engineering

problems and was scrubbed in 2001.

To avoid another bust, commercial space hubs must find creative ways to

supplement tourists' weightless experience by adding attractions such as theme

parks, hotels and restaurants, said Derek Webber, director of Spaceport

Associates, a Maryland-based consulting firm.

"You've got to do your homework," he said, "because not all states will

succeed."

States again

ponder space travel business, UT, 14.5.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2006-05-14-spaceports_x.htm

Making money on the moon seen key to exploration

Fri Apr 28, 2006 8:24 PM ET

Reuters

By Deborah Zabarenko

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Making money on the moon is an

essential part of the U.S. plan for space exploration, NASA officials said on

Friday after a four-day strategy workshop with international space officials and

scientists.

Billed as the first meeting to determine what explorers would do if they return

to the lunar surface after more than three decades, the gathering drew some 180

participants from more than a dozen countries, including China, Russia, Japan

and the nations of the European Space Agency.

Shana Dale, NASA's deputy administrator, said one clear goal was to do business.

"The teams recognize the critical importance of space commerce -- having real

companies going to the moon and making money," Dale said at a telephone news

conference. "The government needs to be a trailblazer and enabler (with) a

desire to see commerce take off."

Other essentials for a global space strategy include public involvement and

participation by international partners, Dale said.

The strategy workshop was the first of several scheduled for this year that aim

to set out specific goals for future space missions to the moon and Mars, as

described by President George W. Bush in 2004 in a sweeping "Vision for Space

Exploration."

Delivered less than a year after the fatal 2003 shuttle Columbia accident, Bush

called for a human return to the moon by 2020 and eventually a human flight to

Mars.

Since the Columbia disaster, in which seven astronauts died, only one space

shuttle has flown, and the shuttle fleet is to be retired by 2010.

A new Crew Exploration Vehicle meant to return humans to the lunar surface is

still on the drawing board, and may not be ready until 2012 or later.

The last time humans went to the moon was aboard NASA's Apollo 17 in 1972. Since

then, China has begun its own human space program and also sent representatives

to this meeting, though Dale said they apparently did not attend the smaller

working sessions.

Aside from the central issues of commerce, international cooperation and public

engagement, the working groups also noted the need for lunar law early in the

process.

David Beatty of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory said an international legal

framework would be helpful in the area of property rights, interoperability

standards and making hardware from various countries work together.

Such laws could govern more prosaic issues as well, Laurie Lesin of NASA's

Goddard Space Flight Center said.

"At our group, we did mention once briefly how we're going to decide which side

of the road we drive on, on the moon," Lesin said with a laugh.

Making money on

the moon seen key to exploration, NYT, 28.4.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=topNews&storyid=2006-04-29T002440Z_01_N28102069_RTRUKOC_0_US-SPACE-EXPLORATION.xml

NASA launches climate satellites

Fri Apr 28, 2006 9:51 AM ET

Reuters

By Irene Klotz

CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida (Reuters) - NASA on Friday launched

two research satellites to help scientists refine computer models that forecast

the weather and chart global climate change.

CloudSat and CALIPSO blasted off aboard an unmanned Delta rocket from Vandenberg

Air Force Base in California at 6:02 a.m. EDT (1002 GMT) after a week of delays

for weather and technical issues. The Boeing-built booster originally had been

slated to fly last year, but a machinists' strike forced several months of

delays.

CloudSat has powerful radar instruments to peer deep into the structure of

clouds and map their water content. Although only about 1 percent of Earth's

water is held in clouds, it plays a crucial role in the planet's weather,

scientists working on the mission said.

"CloudSat will answer basic questions about how rain and snow are produced by

clouds, how rain and snow are distributed worldwide, and how clouds affect the

Earth's climate," principal investigator Graeme Stephens of Colorado State

University said.

Using instruments 1,000 times more powerful than common meteorology radar

CloudSat was designed to render three-dimensional maps of clouds that will

identify the location and form of water molecules.

Complementary and virtually simultaneous studies by sister probe CALIPSO will

pinpoint aerosol particles and track how they interact with clouds and move

through the atmosphere. CALIPSO is an acronym for Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and

Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations.

Aerosols are formed by natural phenomena like forest fires and human activity

such as driving cars. Aerosols are considered a key factor in understanding why

the planet is growing warmer and if anything can be done to stem or reverse the

change.

Computer models predict average surface temperatures on Earth will increase

between 3.5 degrees Celsius and 9 degrees F over the next 100 years.

The uncertainty stems from the role clouds play in moderating heat. Aerosols in

the clouds can either cool the planet by reflecting solar energy back into

space, or increase temperatures by trapping heat in the atmosphere.

"We need to understand the aerosol effect on climate because it counteracts the

effects of greenhouse gases," said CALIPSO principal investigator David Winker

of NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

NASA launches

climate satellites, NYT, 28.4.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=scienceNews&storyid=2006-04-28T135118Z_01_B193600_RTRUKOC_0_US-SPACE-SATELLITES.xml

Griffin: 2011 earliest for new spaceship

Posted 4/25/2006 8:54 PM ET

By Suzanne Gamboa, The Associated Press

USA Today

WASHINGTON — A new spaceship could be ready to replace the

nation's aging shuttle fleet by 2011 — three years ahead of schedule — if

lawmakers added money to NASA's proposed budget, the head of the space agency

told a congressional panel on Tuesday.

NASA Administrator Michael Griffin said that date is the

earliest the new spaceship, or crew exploration vehicle, could be developed no

matter how much money the agency received.

Currently, the target date for building a new vehicle is 2014.

With his pitch to Congress, Griffin underscored a point he has made previously

about completing the spaceship on a faster time frame.

Pressed by Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Fla., Griffin acknowledged an additional $1

billion could accelerate the program's completion.

The shuttle is to be retired in 2010, and lawmakers are concerned about when a

replacement will be ready.

"If money were not an issue — going back to Apollo kinds of days — then I think

it would be no technical problem to have an operational system available in five

to six years," Griffin said after testifying before a subcommittee that oversees

NASA spending.

President Bush's budget calls for a 3.2% increase in NASA spending over last

year. The House and Senate have authorized an additional $1.1 billion, but that

is only a guide. The money must be appropriated by both chambers.

A Senate appropriations subcommittee was to scheduled to meet Wednesday to

consider the proposed increase.

NASA will be shelving its three aging space shuttles in four years. The next

generation of spaceships is supposed to carry astronauts to the moon by 2018 and

eventually to Mars.

The so-called "flight gap" between the shuttles and their replacement could

affect research and American space competitiveness, lawmakers said.

"We don't want a hiatus because we think that puts us in a security risk

position," said Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas.

Griffin: 2011

earliest for new spaceship, UT, 25.4.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2006-04-25-nasa-shuttle-replacement_x.htm

American, Russian, Brazilian return from international

space station

Updated 4/8/2006 10:04 PM

USA Today

ARKALYK, Kazakhstan (AP) — A capsule carrying Brazil's

first astronaut, along with a Russian and an American, landed safely in the

freezing Kazakh steppe early Sunday after separating from the international

space station and hurtling through the Earth's atmosphere.

American astronaut Bill McArthur, Russian cosmonaut Valery Tokarev and Brazilian

Marcos Pontes touched down on target and on schedule.

The TMA-7 landed on its bottom about 30 miles northeast of Arkalyk after what

Mission Control officials called a flawless flight. Officials at Russia's

Mission Control in Korolyov, outside Moscow, reported that the capsule had been

in radio contact for much of the bone-jarring, 3{-hour journey and that all

three crewmembers were feeling well.

Ground crews reached the capsule in northern Kazakhstan, where temperatures

hovered around 13 degrees below zero, within minutes of the landing. McArthur,

shown on a Mission Control screen as he was still strapped inside the capsule,

looked dazed after the 250-mile trip from the space station.

Pontes, seated in a chair outside the capsule, grinned and gave a thumbs-up as

his bulky spacesuit was removed. He was handed a Brazilian flag and a Panama hat

that was pulled out of the capsule — apparently one that he had carried to the

space station in tribute to the Brazilian inventor and aviator Alberto Santos

Dumont, to whom Pontes had dedicated his flight.

The three travelers were given hot tea and wrapped in blankets before being

whisked into a medical tent.

McArthur and Tokarev had spent more than six months on the space station. They

were replaced by Russian commander Pavel Vinogradov and U.S. flight engineer

Jeff Williams, who arrived at the station together with Pontes on April 1.

Pontes had traveled to the station for a weeklong stint.

Speaking at Russian Mission Control, the head of Brazil's space program,

Raimundo Mussi, said Ponte would receive "a big hug from all Brazilians" upon

his return home.

The American space program has depended on the Russians for cargo and astronaut

delivery since the February 2003 Columbia disaster grounded the shuttle fleet.

The shuttle Discovery visited the station last July but problems with the

external fuel tank's foam insulation have cast doubt on when shuttles might

return to flying.

American, Russian,

Brazilian return from international space station, UT, 8.4.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2006-04-08-space-station-return_x.htm

Nasa to put man on far side of moon

March 19, 2006

The Sunday Times

Jonathan Leake , Science Editor

NASA, the American space agency, has unveiled plans for one

of the largest rockets ever built to take a manned mission to the far side of

the moon.

It will ferry a mother ship and lunar lander into Earth orbit to link up with a

smaller rocket carrying the crew. Once united they will head for the moon where

the larger ship will remain in orbit after launching the lunar lander and crew.

The design emerged during a space science conference in Houston, Texas, last

week. The plan is part of Nasa’s “Return to the Moon” programme set in motion by

President George W Bush two years ago.

Under the project, up to four astronauts at a time will land on the far side of

the moon to collect rock samples and carry out research, including looking for

water that might one day support a lunar base.

The scale of the missions is much larger than the earlier Apollo programme,

which is why Nasa will need two separate rockets to take the mother ship and

crew into space.

Some missions will also see manned spacecraft landing in unexplored areas such

as the lunar mountains and on the moon’s south and north poles.

John Connolly, manager of Nasa’s lunar lander project, said the system was

designed to carry crews to almost every part of the moon’s surface.

“The samples they collect and the research they carry out will help solve many

mysteries about the origins and composition of the moon and its suitability as a

base,” he said.

The Apollo programme carried out six lunar landings between 1969 and 1972. The

feat was a triumph, but the technical limitations of the Apollo craft, plus

ignorance of lunar terrain, meant all six missions had to be sent to the moon’s

plains.

These regions, all on the near side of the moon, were the only areas known to be

flat enough for a safe landing. This has frustrated scientists because the

samples collected by the six missions are all similar. They are also thought to

be younger than lunar mountain rocks.

The far side — so called because it always faces away from the Earth — was first

photographed in 1959 by a Russian probe. In 1968 the astronauts of Apollo 8

became the first to view it directly.

The evidence gathered by such missions was enough to deter any attempt to land

because most of the far side appeared to be covered in large craters.

Additionally, any craft landing there would be cut off from radio contact with

Earth.

Connolly believes, however, that Nasa will be able to overcome such problems by

sending a series of robotic probes ahead of the manned missions.

The first of these, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, to be launched in 2008,

will map the moon’s surface in detail.

Cameras will photograph the surface, backed by a laser altimeter to create a

three-dimensional relief map from which Nasa can identify landing sites.

Then, from 2010, a series of “companion lander” missions will carry out test

landings on selected sites to see if they are worth a visit by humans.

The final element will be a system of communications satellites, dubbed the

“lunar internet”, so astronauts will be able to relay signals to Earth from any

part of the moon.

Connolly said the first humans could arrive as early as 2015, although 2018 was

more likely. The agency would then aim to send two crews to the moon each year

for up to five years. The programme will cost around £56 billion and may also be

used to test technology for any future mission to Mars.

Some have questioned whether the programme will produce enough good science to

justify the costs.

Manuel Grande, head of the planetary science group at the Rutherford Appleton

Laboratory in Oxfordshire, dismissed such fears. “Finding out more about the

moon will help us understand where the Earth and moon came from,” he said.

“There do not have to be good scientific reasons . . . It’s like going up

Everest; we want to go to places like the moon and Mars just because they are

there.”

Nasa to put man on

far side of moon, ST, 19.3.2006,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2089-2092495,00.html

A Bold Plan to Go Where Men Have Gone Before

February 5, 2006

The New York Times

By LESLIE WAYNE

EL SEGUNDO, Calif.

ASK Elon Musk what he wants to do with his life — after

having amassed a $300 million fortune from the Internet — and the answer is

surprising. At 34, he says he is too young to retire. Philanthropy is a bit

staid. Starting another Web-based venture is hardly a challenge, not for a man

who bought the idea for PayPal, built it up and then sold it to eBay for $1.5

billion.

In seeking a new direction in life that would be as ambitious as his dreams, Mr.

Musk has picked a doozy: cheap and reliable access to space.

Making money from space is a road that several other self-made millionaires have

traveled, from a Texas banker named Andrew Beal to one of Microsoft's

co-founders, Paul G. Allen. There have been enough of them to warrant a mocking

nickname: "thrillionaires." And so far their efforts have either ended in

failure or have been just ventures in "space tourism" that brought test pilots

to the fringe of space.

Mr. Musk wants more, and he has put $100 million of his fortune on the line to

try to get it. His goal is to make a business out of inexpensively launching

satellites into orbit. Inexpensive, of course, is a relative term, in a business

where launchings of private commercial weather, telecommunications and other

payloads start at $30 million and go up to $85 million or more.

Through his company, Space Explorations Technology, or SpaceX, Mr. Musk wants to

send things to space for one-third of the going rate or less — even bringing

down the price to $7 million for small payloads to low Earth orbit — with a

series of simple rockets of his own design. His goal is to build a Volkswagen of

the cosmos, a bare-bones and dirt-cheap rocket that will go into space and

return, to be used again and again. Commercial launchings currently cost $5,000

to $10,000 per pound of payload; Mr. Musk says his simple rockets could do it

for $1,000 a pound.

His first rocket, the Falcon 1, is a two-stage, liquid fuel design that is

scheduled to lift off on Wednesday from a United States Army facility on Omelek

Island in the Kwajalein Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands. On board will be a

43-pound satellite, the FalconSAT-2, which was designed by Air Force Academy

cadets to study the ionosphere.

THE launching has been postponed twice for technical reasons, but if it

succeeds, it will move SpaceX closer to filling some of the $200 million in firm

launching orders already placed by the Pentagon, foreign governments and private

companies.

Less clear is whether a success will also silence the many skeptics who have

seen wealthy space dreamers fail in the past.

"This is an enormously difficult business to make money in," said John E. Pike,

a space policy analyst at GlobalSecurity.Org, a nonprofit group in Alexandria,

Va., that analyzes national security issues. "The best way to make a small

fortune in space is to start out with a large one. New rocket science has a high

mortality rate, and we don't know what he's got his hands on until he's flown it

a half-dozen times."

Part dreamer and part realist, Mr. Musk says he was drawn to the project not

only because he has long been fascinated by space — he has a degree in physics

from the University of Pennsylvania — but also because he sees a market

opportunity in America's declining share of the world's satellite-launching

business.

In the commercial market, the United States' two big rocket giants, Lockheed

Martin and Boeing, have been priced out by lower-cost competitors from Russia,

Ukraine and France. Lockheed's Atlas 5 had only one commercial order in 2005,

compared with 22 in 1998. Boeing has withdrawn its Delta 4 rocket from the

commercial market and relies exclusively on business from the United States

government.

At stake is a market that was worth $4 billion last year, when governments and

businesses paid for 55 launchings, according to the Federal Aviation

Administration. Of those, 18 were commercial, with a value of $1 billion.

American companies compete for commercial orders only by teaming with foreign

partners — often former cold-war foes. Lockheed has teamed up with Khrunichev

State Research of Russia to form International Launch Services, which mainly

uses Russia's Proton rockets. Boeing has joined with several nations to form a

consortium called the Sea Launch; it uses the Ukrainian Zenit 3SL to put up

commercial payloads.

Mr. Musk says he wants to develop an all-American option that will be

price-competitive and break the duopoly of Lockheed and Boeing on contracts with

the federal government. Ultimately, he wants to send people into space, to the

moon and beyond.

"We have to do something dramatic to reduce the cost of getting to space," said

Mr. Musk in an interview in his cubicle at SpaceX's offices here. "If we can get

the cost low, we can extend life to another planet.

"I want to help make humanity a space-faring civilization," he said with

disarming — or alarming — candor.

SpaceX's first effort, the Falcon 1, will not put anyone on the moon. It is

designed to send small satellites — typically communications and scientific

payloads weighing less than 1,000 pounds — into low orbit, which is up to 300

miles above the Earth. The two-stage Falcon 1 is designed to be mostly

recyclable, with part of it falling into the ocean to be picked up and used

again.

The Falcon 1 will charge $6.9 million a launching. It is intended to go head to

head with the Pegasus rocket made by the Orbital Sciences Corporation of Dulles,

Va., which charges $25 million to $30 million for the same launching, as well as

rockets from such newcomers as India and Israel.

Next up are the Falcon 5, the same rocket with five engines, and the Falcon 9,

with nine engines. The Falcon 9 would bring SpaceX into direct competition with

Boeing's Delta 4 and Lockheed's Atlas 5 in the so-called heavy-lift market, in

which the United States government is the main customer. A Falcon 5 plans to

launch 8,000-pound payloads for $18 million, a third of the price of

competitors. The Falcon 9, which will put 10 tons of payload as far as 22,000

miles into the sky, will cost $27 million per launching. The same launching by

Lockheed or Boeing would be about $70 million to $80 million.

Expecting that it can compete in this market, SpaceX has sued Boeing and

Lockheed in federal court in California, seeking to prevent them from combining

their rocket units in a joint venture called the United Launch Alliance, which

would have a lock on $32 billion in Air Force launchings through 2011.

"SpaceX has the potential of saving the U.S. government $1 billion a year," Mr.

Musk said. "We are opposed to creating an entrenched monopoly with no realistic

means for anyone to compete."

A native of Pretoria, South Africa, Mr. Musk moved by himself at age 17 to

Canada, where he briefly attended Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. He

later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he received two

undergraduate degrees — one in theoretical physics and the other in business

from the Wharton School. He enrolled in the graduate physics program at Stanford

in 1995 but dropped out within days to become an Internet entrepreneur.

His first big hit was Zip2, a Web-based ad company that he sold in 1999 for $307

million. (The New York Times Company was an investor in Zip2.) He moved on to

another Web venture, involving electronic payments over the Internet — even

though, as skeptics noted, he lacked experience in banking. That business

ultimately became PayPal, which eBay bought for $1.5 billion in 2002.

By the time Mr. Musk was 30, he had amassed $300 million and was pondering his

future.

His first thoughts were of philanthropy — and of space. He came up with the idea

of "Mars Oasis," an effort to send a small greenhouse to Mars to gather

scientific information and create excitement about space travel — or so Mr. Musk

thought. His idea was quickly derailed by the extraordinary cost of getting to

space, but that led him to wonder why technology had not brought down the cost

of space exploration or led to more of it. And that led him to found SpaceX in

2002.

Every day since then, Mr. Musk has driven to a gritty industrial zone, where he

puts in long days at SpaceX. Still, he allows himself a few perks of the newly

rich: a big house in Los Angeles, a $1 million McLaren F1 sports car, and a

Dassault Falcon 900 business jet, which he sometimes uses to ferry his staff to

the Marshall Islands.

In some ways, SpaceX is a throwback to his dot-com days. Many of the 160

employees, including former engineers from Boeing and other aerospace companies,

are on a first-name basis with him. One building houses a Ping-Pong table;

another has a Segway. All employees — who call themselves "SpaceExers" — have

received stock options that could make them millionaires someday. In one spot, a

blue tarp covers a small piece of a rocket that Mr. Musk casually described as a

"top secret" project and joked about putting a sign on it saying so. Indeed, it

was a part for a launching scheduled by the Pentagon, which already has $100

million of SpaceX business lined up. He has another $100 million in launchings

from the government of Malaysia, the Swedish Space Corporation and several

American companies, including Bigelow Aerospace, which is planning to build a

private space station.

TheFalcon 1 flight this week is for the Air Force and the Defense Advanced

Research Projects Agency, the Pentagon's research and development arm. "DARPA is

excited about the launch," said Steven Walker, the DARPA manager for the Falcon

program. "A successful launch demonstration will change the way we do space

launch in this country."

WHAT sets SpaceX apart from other rocket makers is that the boldness of its

ambition is matched by the modesty of its design. To meet his goal of a cheap

and reliable rocket, Mr. Musk is producing a basic design, with fewer

opportunities for systems to fail — even if it means some technical compromises

with performance. "SpaceX is optimizing for simplicity rather than performance,

and that's what sets it apart from the others," said Jeffrey Foust, an analyst

at the Futron Corporation, an aerospace consulting firm. "When you have a

limited number of things that could fail, you can increase a rocket's

reliability."

Where most other rockets have multiple stages and multiple engines, the Falcon

will have just two stages, each with one engine. Most of SpaceX's stages are

designed to be reusable. Although fishing small used rockets out of a vast ocean

can be difficult, Mr. Musk says that it is cheaper than building a new one every

time.

"Throwing away multimillion-dollar rocket stages every flight," he said, "makes

no more sense than chucking away a 747 after every flight."

Instead of buying engines from established suppliers, Mr. Musk has designed his

own and built them in-house. The bigger first-stage engine, called the Merlin,

is a model of 1960's technology, a simple "pintle" engine that has only one fuel

injector rather than the costly showerhead of injectors used in most rockets.

"The Merlin is much more analogous to a truck engine than a sports car engine,

which is how all other engines are designed," he said. "Instead of designing it

to the bleeding edge of performance and drawing out every last ounce of thrust,

we designed Merlin to be easy to build, easy to fix and robust. It can take a

beating and still keep going."

AS such remarks make clear, economy is everything at SpaceX. While Boeing and

Lockheed typically have more than 200 people in their mission control launching

centers, SpaceX will have 23, in part because all the Falcon's manufacturing is

done in the factory and nothing is left to be assembled at the launching pad.

SpaceX plans some launchings for Vandenberg Air Force Base near Lompoc, Calif.,

where it will move its mission control, which is now housed in a truck in

SpaceX's parking lot.

SpaceX also has a 300-acre test site in McGregor, Tex., that it bought from Mr.

Beal, the Texas banker, after he abandoned his private space-launching effort.

He closed his company, Beal Aerospace, in 2000, complaining that Boeing,

Lockheed and NASA had a lock on launchings and that small entrepreneurs could

not compete against these government-subsidized ventures.

Mr. Beal and others have said that the biggest problems for space entrepreneurs

are more political than technical. For Mr. Musk, wealth provides some protection

— a point that even critics like Mr. Pike of GlobalSecurity.Org concede. "He's

got the advantage of deep pockets," Mr. Pike said.

For the moment, Mr. Musk is bankrolling SpaceX alone. But if he can launch

Falcon 1, he anticipates getting venture capital money along with more

commercial orders.

"There is concern that the United States is losing its competitive edge in

commercial space launches," said Mr. Foust, the Futron analyst. "If SpaceX can

provide low-cost launches that are reliable, it could turn the tide. He's

certainly got the mind-set, the team and the money."

Most other "thrillionaire" ventures revolve around space tourism and suborbital

trips, which are less challenging and costly.

Mr. Allen, the billionaire co-founder of Microsoft, provided $25 million to help

bankroll SpaceShipOne, which was designed by the aeronautical engineer Burt

Rutan and won the $10 million Ansari X Prize in October 2004 for being the first

private manned spacecraft to reach suborbital space twice. Mr. Rutan is now

designing a bigger version for Virgin Galactic, the space tourism venture of Sir

Richard Branson, who founded Virgin Atlantic Airways.

The engines on Mr. Rutan's SpaceShipOne came from SpaceDev, founded by Jim

Benson, a computer engineer who had started two software companies. SpaceDev

plans to put satellites on Falcon 1 and is developing the "Dream Chaser" to

pursue suborbital space tourism.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com, has started Blue Origin to develop a

three-person suborbital rocket. And John Carmack, developer of the Doom and

Quake computer games, has founded Armadillo Aerospace near Dallas and has

already put in $1 million to build a suborbital craft.

Space tourism presents no threat to Boeing or Lockheed, but Mr. Musk could. The

two companies are quick to dismiss him. "Launching into space is an extremely

challenging and complex business," said Dan Beck, a Boeing spokesman, adding:

"For SpaceX to be considered a potential competitor they need to have a launch."

Tom Jurkowsky, a spokesman for Lockheed, had a similar view. "SpaceX needs to

prove themselves," he said, "and thus far they have been unable to demonstrate

that they are a competitor."

Still, some cheer on Mr. Musk.

"I'm particularly happy to see it happen," said Robert Sackheim, chief

propulsion engineer at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and an early

consultant to Mr. Musk. "Their engine design is less than perfect, but it is

good enough. I think he is doing all the right things. This can be an incredibly

important advance to the country."

A Bold Plan to Go

Where Men Have Gone Before, NYT, 5.2.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/05/business/yourmoney/05rocket.html

|